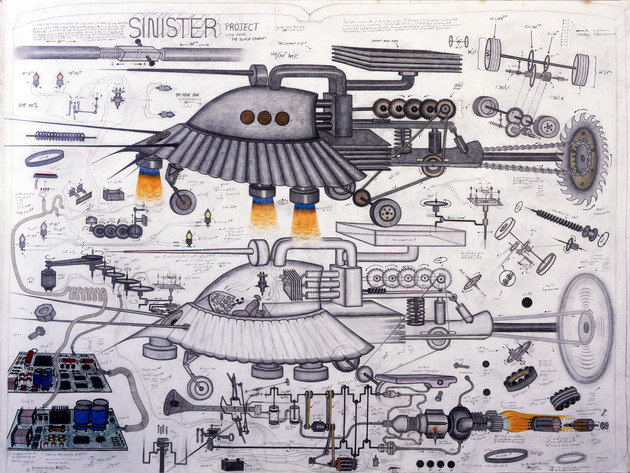

Responding with imagination to the brutality and violence of Sierra Leone’s civil war (1991-2002), Abu Bakarr Mansaray’s monumental drawing Sinister Project depicts a fictitious war machine with careful detail that reveals the artist’s background in science and engineering.

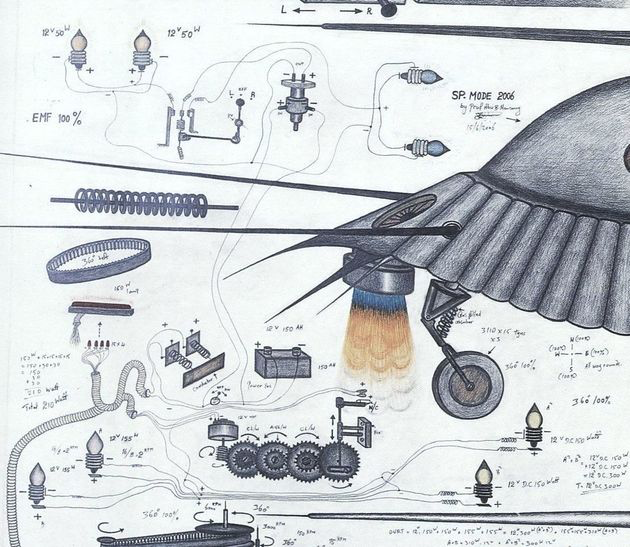

Sierra Leonean artist Abu Bakarr Mansaray’s Sinister Project (2006) actualizes concealed knowledge and power by making it visible (fig. 1). Labeled a “Top Secret Project”, whose code name is “The Black Storm”, it is crowded with complicated calculations, numerical denominations, and conspiratorial language. The large-scale drawing—meticulously rendered in graphite and colored ink—diagrams, dissects, and defines every component part of a violent and destructive arthropodal aircraft that, according to the artist, was built before the existence of man to “cause disaster.” Mansaray has surrounded illustrations of the interior of the alien craft and its impenetrable exoskeleton with the vessel’s emptied mechanics, with every tube, bulb, cog, spring, screw, and bolt carefully represented. The work is a maze of lines connecting each part to its mate, instructing as it displays the internal engineering (fig. 2). Mansaray signed the work multiple times and interwove written narrative about the craft into the drawing itself, anxious to control, confuse, and claim ownership over the information.

Sinister Project is one in a series of diagrams and sculptural objects the artist has created throughout his thirty-year career that depict fantastic, militaristic, and futuristic war machines. He presents these machines and the science behind them as his own research, undertaken as “Proff Abu.” This claim is crucial. The artist left school and his hometown of Tongo in 1987 to settle in Freetown, Sierra Leone, where he independently studied engineering, chemistry, physics, electronics, and mathematics, subjects that activated his imagination and gave him access to the knowledge systems that order our physical world. Mansaray’s monumental drawings reflect the scientific illustration techniques that he observed and learned over the course of his studies, overwhelming the viewer with their scale and exhaustive visualization of mechanical detail. The Freetown that Mansaray entered as a youth was historically a cosmopolitan, urban coastal center, settled by freed slaves arriving from England and the Americas in the late eighteenth and early to mid-nineteenth centuries, before falling subject to a British protectorate, which remained in place until 1961.1Vera Viditz-Ward narrates the documentation of Freetown’s cosmopolitan Creole elite through photography from as early as the mid-nineteenth century, demonstrating the city’s early and widespread access to modern technology. Vera Viditz-Ward, “Photography in Sierra Leone, 1850–1918,” Africa 57, no. 4 (1987): 510–18. The multicultural and multilingual Creole culture fostered within the city encouraged the emergence of modern artists in the late colonial and early postcolonial period, including Miranda Burney-Nicol (Olayinka; 1927–1996) and Hassan Bangura (born 1933), who drew upon Sierra Leone’s complex and multiple cultural traditions in their multidisciplinary work.2Though very few studies of modernism in Sierra Leone have been written, anthropologist Simon Ottenberg’s biography of artist Miranda Burney-Nicol documents this artist’s multi-sited and multidisciplinary artistic practice. Simon Ottenberg, Olayinka: A Woman’s View; The Life of an African Modern Artist (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 2014).

Mansaray’s Freetown was not the same cosmopolitan center of his artistic forebears. In fact, the dark reality in which Mansaray’s war machines exist is far from fantastical. Mansaray came up in his career during Sierra Leone’s brutal civil war (1991–2002). Those who could, left the country in the years leading up to this period of terrible destruction to avoid the impending economic, political, and social erosion. During the war, the Revolutionary United Front (RUF), a rebel group backed by Charles Taylor, then president of Liberia, combated the forces of the Sierra Leonean government and its allies for more than a decade.3See the following for an account of the civil war in Sierra Leone: P. Richards, “Sierra Leone,” in Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes against Humanity, ed. Dinah Shelton (Detroit: Macmillan Reference, 2005). Mansaray’s sketches and sculptures from the first years of the conflict are mired in his personal experience of having lived through the spectacle of violence and social upheaval.

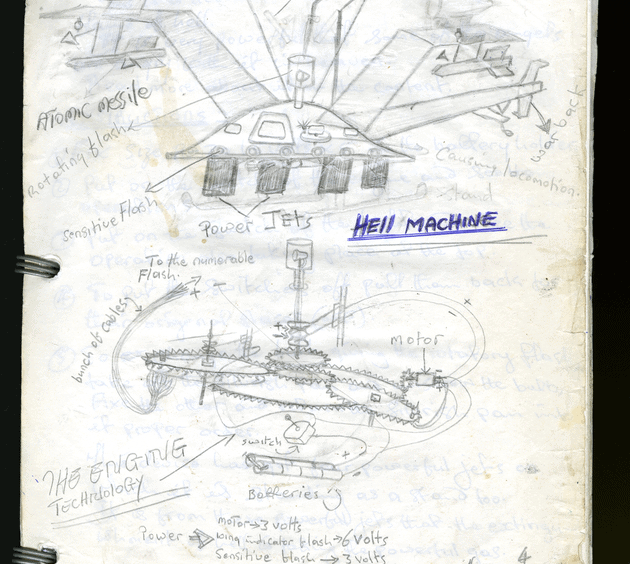

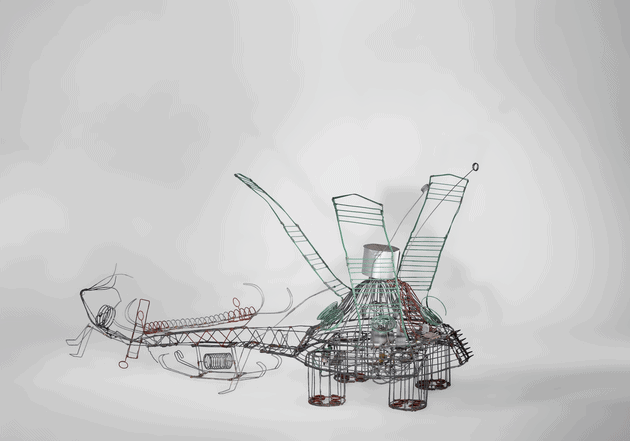

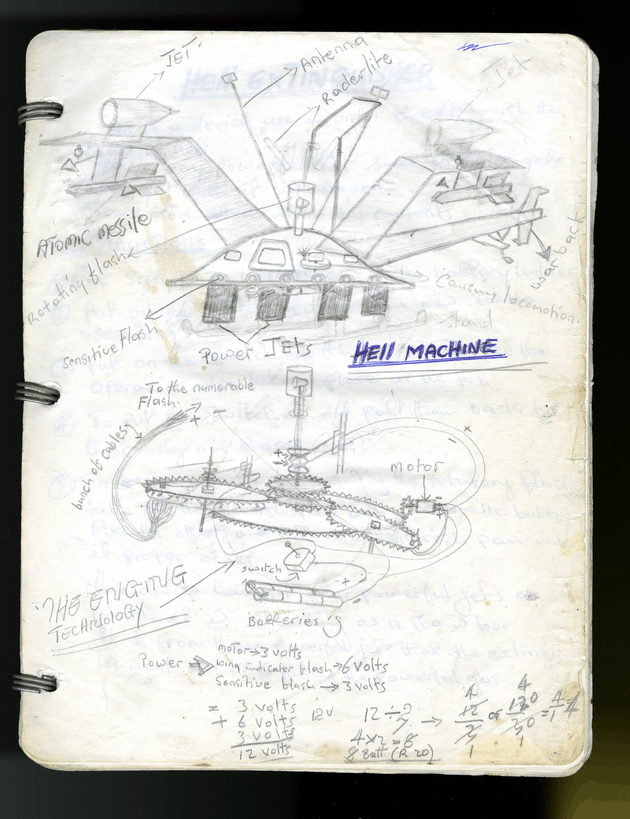

Mansaray’s early sculptures appropriate the popular art found throughout Africa of decorative objects and toys fashioned from scraps of wire and iron (fig. 3). Generally associated with children, these works often take the shape of cars or airplanes, enabling their makers to handle and vicariously own the power such vehicles symbolize.4For an analysis of the creation of wire toys among children in apartheid South Africa, see John Peffer, “Mandela Rides a Casspir,” in Through African Eyes: The European in African Art, 1500 to Present, ed. Nii Otokunor Quarcoopome (Detroit: Detroit Institute of Arts, 2010), 115–27. The politics of play that they allow assume a tragic reality for those children, forced to participate in the conflict in Sierra Leone as soldiers and as victims. Mansaray’s metal wire sculpture Hell Extinguisher (1992; fig. 4) and its preparatory sketch Hell Machine (1992; fig. 5), for example, speak to his own desire to exert influence in a world over which he had no control, to build a machine that can “extinguish the fires of Hell.” The artist has declared, “I like doing strange drawings and also designing complicated machines based on scientific ideas that sometimes exceed human imagination.”5“Abu Bakarr Mansaray,” The Insiders: Selected Works (1989–2009) from the Contemporary African Art Collection of Jean Pigozzi, eds. Suzanne Pagé, André Magnin, Angeline Scherf, and Ludovic Delalande (Paris: Fondation Louis Vuitton and Editions Dilecta, 2017), 150. Through his work and his studies, the artist imagined himself out of his reality. His work first gained international recognition in 1993, when he won a UNESCO Prize for the Promotion of the Arts. No longer safe in war-torn and poverty-stricken Sierra Leone, Mansaray escaped to the Netherlands in 1998 as a refugee, avoiding the RUF’s January 1999 massacre in Freetown, when citizens were terrorized through systematized amputation by machete, rape, and murder.6“Getting Away with Murder, Mutilation and Rape: New Testimony from Sierra Leone,” Human Rights Watch, June 24, 1999, https://www.hrw.org/report/1999/06/24/getting-away-murder-mutilation-and-rape/new-testimony-sierra-leone.

Mansaray now resides between Harlingen, Netherlands, and Freetown. His work has been shown in international exhibitions including Simon Njami’s landmark Africa Remix: Contemporary Art of a Continent (2004)7Simon Njami, Africa Remix: Contemporary Art of a Continent (Johannesburg: Jacana Media, 2007), 210–11. and Okwui Enwezor’s groundbreaking Venice Biennale All the World’s Futures (2015).8Ugochukwu-Smooth Nzewi, “Abu Bakarr Mansaray,” in All the World’s Futures [short guide], ed. Okwui Enwezor (Venice: Marsilio Editori, 2015), 168–69. Though removed from wartime, the artist’s work is still consumed by memory of the conflict, providing the space to perpetually relive and resolve the trauma of war.9Other artists from Sierra Leone have used artmaking to represent the atrocities of their nation’s civil war. Patrick K. Muana and Chris Corcoran, eds., Representations of Violence: Art about the Sierra Leone Civil War (Madison, WI: 21st Century African Youth Movement, 2005). Produced in the wake of the controversial Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), which aimed to begin a process of national healing, Mansaray’s Sinister Project explicates as it obfuscates with its overwhelming visual detail. Participation in the TRC hearings was often contested, foregrounding the risks of truth-telling in a place where torture and death had become everyday realities.10Rosanne Kennedy, “Reparative Transnationalism: The Friction and Fiction of Remembering in Sierra Leone,” Memory Studies 11, no. 3 (2018): 350. Sinister Project visualizes the tension between known and unknown truths, and the semblance of control such knowledge bestows. Mansaray’s drawings and sculptures are not simply fantastical machines, but also incisive commentaries on the power associated with command over hierarchies of knowledge. Combining the visual languages of African popular arts with the conventions of mechanical and scientific illustration, Mansaray grounds his work in both a physical reality, and a reality of his own making.

- 1Vera Viditz-Ward narrates the documentation of Freetown’s cosmopolitan Creole elite through photography from as early as the mid-nineteenth century, demonstrating the city’s early and widespread access to modern technology. Vera Viditz-Ward, “Photography in Sierra Leone, 1850–1918,” Africa 57, no. 4 (1987): 510–18.

- 2Though very few studies of modernism in Sierra Leone have been written, anthropologist Simon Ottenberg’s biography of artist Miranda Burney-Nicol documents this artist’s multi-sited and multidisciplinary artistic practice. Simon Ottenberg, Olayinka: A Woman’s View; The Life of an African Modern Artist (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 2014).

- 3See the following for an account of the civil war in Sierra Leone: P. Richards, “Sierra Leone,” in Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes against Humanity, ed. Dinah Shelton (Detroit: Macmillan Reference, 2005).

- 4For an analysis of the creation of wire toys among children in apartheid South Africa, see John Peffer, “Mandela Rides a Casspir,” in Through African Eyes: The European in African Art, 1500 to Present, ed. Nii Otokunor Quarcoopome (Detroit: Detroit Institute of Arts, 2010), 115–27.

- 5“Abu Bakarr Mansaray,” The Insiders: Selected Works (1989–2009) from the Contemporary African Art Collection of Jean Pigozzi, eds. Suzanne Pagé, André Magnin, Angeline Scherf, and Ludovic Delalande (Paris: Fondation Louis Vuitton and Editions Dilecta, 2017), 150.

- 6“Getting Away with Murder, Mutilation and Rape: New Testimony from Sierra Leone,” Human Rights Watch, June 24, 1999, https://www.hrw.org/report/1999/06/24/getting-away-murder-mutilation-and-rape/new-testimony-sierra-leone.

- 7Simon Njami, Africa Remix: Contemporary Art of a Continent (Johannesburg: Jacana Media, 2007), 210–11.

- 8Ugochukwu-Smooth Nzewi, “Abu Bakarr Mansaray,” in All the World’s Futures [short guide], ed. Okwui Enwezor (Venice: Marsilio Editori, 2015), 168–69.

- 9Other artists from Sierra Leone have used artmaking to represent the atrocities of their nation’s civil war. Patrick K. Muana and Chris Corcoran, eds., Representations of Violence: Art about the Sierra Leone Civil War (Madison, WI: 21st Century African Youth Movement, 2005).

- 10Rosanne Kennedy, “Reparative Transnationalism: The Friction and Fiction of Remembering in Sierra Leone,” Memory Studies 11, no. 3 (2018): 350.