A look at the history of the modern house suggests that domestic living takes shape in the intermediate, and sometimes contentious, space between the aspirations of the dweller and architect. Through its arrangement of separate but adjacent individual units, Moriyama House by Ryue Nishizawa proposes a mode of semi-communal living, building a new sociality between its inhabitants.

What should the modern house look like?

This simple question has been central, at least at some point, to the practice of almost every modern architect. There is hardly any other architectural commission that is more personal, loaded, and vulnerable than one’s own house. Architect and client are immediately entangled in one of the most intimate kinds of relationship―and not all such relationships end well. Architects are often accused of imposing their own visions of modern domesticity on their clients.1Adolf Loos, “The Poor Little Rich Man,” in Spoken into the Void: Collected Essays by Adolf Loos, 1897–1900, trans. Jane O. Newman and John H. Smith, Oppositions Books (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1982), 124–27. In fact, the history of almost every prominent modern house of the twentieth century involves some kind of face-off between architect and patron, as well as failed aspirations, unfulfilled wishes, conflicting agendas, misunderstandings, grudges, threats, and even lawsuits.2See, for example, Tim Benton, “Villa Savoye and the Architect’s Practice,” in Le Corbusier, ed. H. Allen Brooks (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987), 83–105; Beatriz Colomina, “A House of Ill Repute: E. 1027,” in Interiors, eds. Johanna Burton et al. (Annandale-on-Hudson: Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College; Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2012), 110–19; Alice T. Friedman, “Domestic Differences: Edith Farnsworth, Mies van der Rohe, and the Gendered Body,” in Not at Home: The Suppression of Domesticity in Modern Art and Architecture, ed. Christopher Reed (London: Thames and Hudson, 1996), 179–92; Rem Koolhaas and Bruce Mau, “Obstacles: Villa Dall’Ava, St. Cloud, Paris, France, Completed 1991,” in S, M, L, XL (New York: Monacelli Press, 1995), 132–93. The full story is found not only in hand-drawn sketches, architectural models, and publicity photographs but also in the messier, less classifiable realm of the architectural process―in letters of complaint, in personal diaries, and in legal documents. It is in the in-between that the type of life enabled by a house is truly molded.

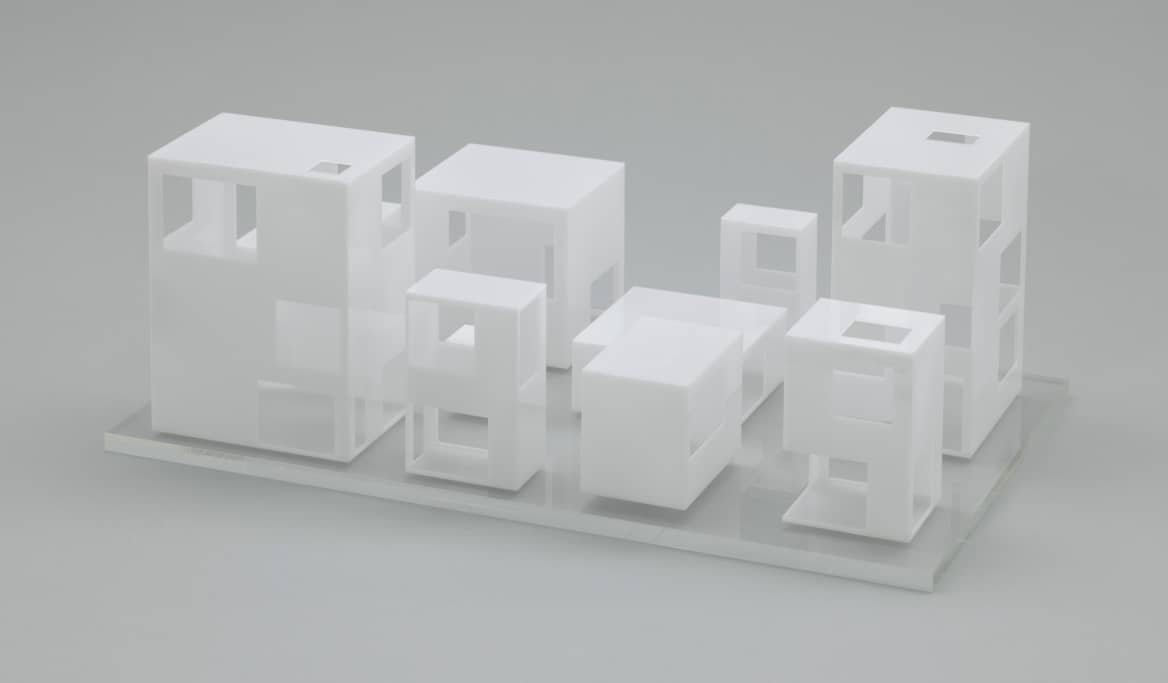

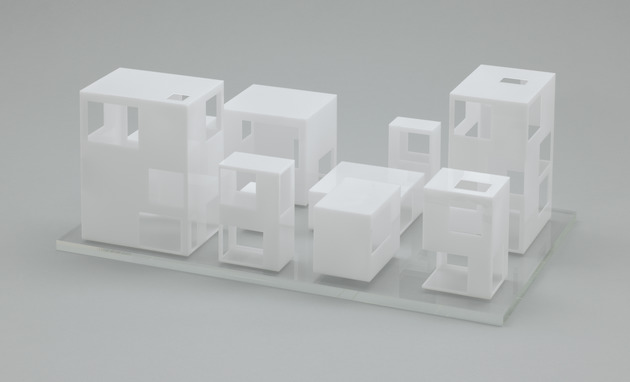

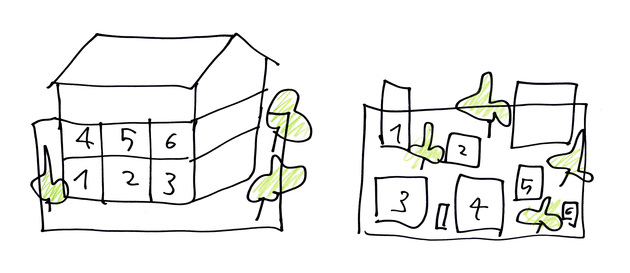

Take, for example, the Moriyama House in Tokyo (2002–2005), designed by Japanese architect Ryue Nishizawa (born 1966). At first glance, its layout hardly resembles that of a typical house. Instead of a single architectural enclosure, the Moriyama House comprises ten prismatic volumes, meticulously arranged at right angles to one another and the site. As if mutually repelled by an invisible force, the volumes never touch. Made of thin sheets of steel, they are painted a clinical white. Every opening is square or rectangular, and precisely cut, as if with a scalpel. The architectural representations of the project give the same impression. For example, consider the three-dimensional model, which betrays no signs of life. There are no material choices, tectonic details, or human figures to be seen here. The whole arrangement could be easily misunderstood as sterile, scale-less, maybe even borderline inhumane. Who was this idea of domesticity dreamt up for? What purpose does it truly serve? The architect’s ambitions and fantasies or the client’s wishes and needs?

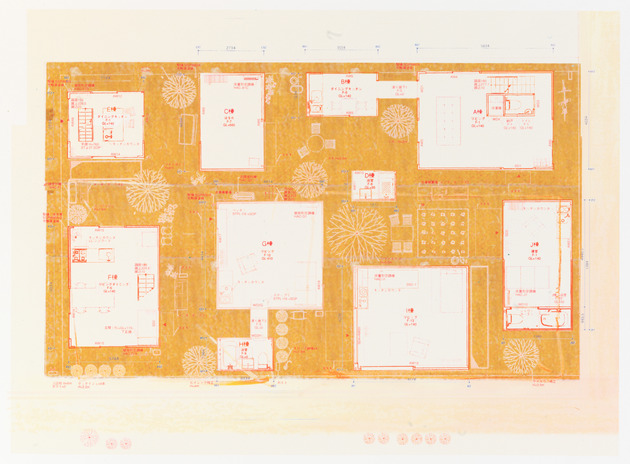

The client, Yasuo Moriyama, is a middle-age man who has never left Japan―or for that matter, his home city of Tokyo. In the early 2000s, he wrote to Nishizawa, asking the architect to design a house for him. Nishizawa is said to have responded, “You don’t need a house you need a village in a forest.”3Quoted in Moriyama-San, directed by Ila Bekâ and Louise Lemoine (Bordeaux: Bekâ & Partners, 2017). Although one may wonder if this was a professional recommendation or a diagnosis, Moriyama decided to go along with it. The architect’s design called for breaking an overall structure into “units,” which he simply ordered from A to I. Many of the separate parts serve a single function, such as that of living room (Unit C) or bathroom (Unit D).4“Ryue Nishizawa,” GA Houses, no. 100 (August 2007): 272–73. Five of them, however, are more complete in and of themselves; each including its own small kitchenette and bathroom, and thus functioning as an independent “mini-house.”5“Moriyama House,”Lotus International, no. 163 (July 2017): 113. Placing the units almost equidistant across the entire surface of the site allowed each mini-house to have its own small garden6“Ryue Nishizawa: Moriyama House, Tokyo, Japan,” GA Houses, no. 90 (November 2005): 68; “Moriyama House, Tokyo, 2005: Office of Ryue Nishizawa,” JA: Japan Architect, no. 66 (July 2007): 24; “Ryue Nishizawa: Moriyama House,” Arquine, no. 47 (Spring 2009): 44; “Moriyama House,” a+u: Architecture and Urbanism, no. 512 (May 2013): 86–92.―a space in which to plant vegetables, hang laundry, or do work out in the open.

At the time of the commission, Moriyama ran a liquor store. Yet all he really wanted to do was be at home, where he could immerse himself in his vast collections of cult films and musical recordings―and, above all, read.7Rob Gregory, “Cubic Commune: Six Houses, Tokyo,” Architectural Review, no. 1326 (August 2007): 41. Renting out the five mini-houses on his plot would allow him to give up his store and to spend every day among his favorite things.8Ryue Nishizawa, “Moriyama House, Tokyo, Japan,” GA Houses, no. 74 (March 2003): 140; “Casa Moriyama, Ohta-Ku, Tokio, Japón = Moriyama House, Ohta-Ku, Tokyo, Japan,” El Croquis, nos. 121/122: SANAA: Kazuyo Sejima + Ryue Nishizawa, 1998–2004: Ocean of Air (Madrid: El Croquis Editorial, 2004): 364. When Moriyama’s mother, his only living family member, passed away in 2006, he was left alone in the world, with only his treasured dog to accompany him on regular visits to his family’s nearby cemetery plot.

Not long after, Moriyami rented out the five mini-houses in his “village.” Having been featured in numerous publications around the world, even before being completed, the project had achieved a certain cult status both inside and outside of Japan. Curious architects and students flocked to see it and to take pictures. It should, therefore, come as no surprise that most of Moriyama’s first tenants were younger architects from Nishizawa’s office, and an editor of a contemporary architecture magazine.9Maggie Kinser Hohle, “Building Blocks,” Dwell 7, no. 2 (December 7, 2006): 148–55. Moriyama’s “village in the forest” soon resembled a designers’ colony. Following in Moriyama’s footsteps, many of his new neighbors began to work from home, blurring the line between life and work, solitude and togetherness. Moriyama’s daily life wasn’t impacted only by the architecture of the house, it now seemed also to be taken over by architects.

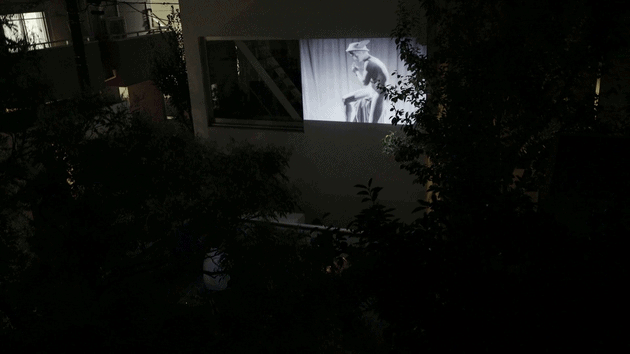

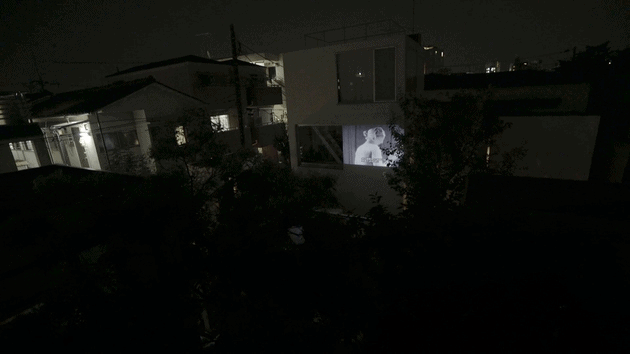

Soon, the neighborhood-like arrangement of ten parallelepiped mini-houses resulted in an unexpected social network: a new kind of semi-communal lifestyle. Whereas none of the individual units of the house were intended for communal use, Moriyama’s living room (Unit C) soon served as a kind of common room. There, residents often lunch together, enjoy a cold beer on a hot summer day, or screen a film from the roof. As Moriyami has put it, “This space gives you the freedom to do anything you like, and it makes you want to.”10Ibid., 148. Similarly, the network of earth-covered alleyways between the units has become loci for everyday interactions―to chat, drink sake, or light fireworks.

The Moriyama House is an architectural device that facilitates mingling. Its composition encourages reclusive occupants to cross thresholds, to migrate, and to step outside their comfort zones, just by taking a few steps in one direction or another.11“Moriyama cohouse: disordine apparente di progetti d’autore = Moriyama Co-House: Apparent confusion of projects by famous architects,” Lotus International, no. 132 (November 2007): 5–10. Every such outing is a short promenade across an urban microcosm.12“Casa Moriyama a Tokyo = Moriyama House, Tokyo,” L’industrial delle construzioni 42, no. 404 (December 2008): 35. In remaining within the bounds of the house for several days at a time, one still ventures outside―even if only briefly, when traveling from one unit to another. Along the meandering garden paths, one catches a glimpse of street life beyond the site of the house: a slow-moving scooter, the postman on his or her rounds, a woman dressed in a traditional kimono and rolling a plastic suitcase. The more one looks into this arrangement, the more its seemingly dismembered scheme becomes less of an architectural imposition and more of a communal life support for the solitary dwellers who have gravitated toward it.

Could it be that this “life in between” is not a mere side effect, but rather the active ingredient in an architectural prescription? In recent decades, the devastating effects of loneliness in Japan, especially among the elderly, have been identified as an urgent, public health concern.13Emiko Takagi and Yasuhiko Saito, “Older Parents’ Loneliness and Family Relationships in Japan,” Ageing International 40, no. 4 (December 2015): 353–75; Tim Tiefenbach and Phoebe Stella Holdgrün, “Happiness through Participation in Neighborhood Associations in Japan? The Impact of Loneliness and Voluntariness,” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 26, no. 1 (February 2015): 69–97; Hiromi Taniguchi and Gayle Kaufman, “Self-Construal, Social Support, and Loneliness in Japan,” Applied Research in Quality of Life 14, no. 4 (September 2019): 941–60, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9636-x. More and more people live by themselves, often without a family member or close friend nearby. Despite their proximity to one another, the mini-houses ensure a level of privacy, with the windows of one unit never directly facing those of another.14Akira Suzuki, “Puzzle Housing,” Domus, no. 888 (January 2006): 43; “Casa Moriyama, Tokio, Japón, 2002–2005 = Moriyama House, Tokyo, Japan, 2002–2005,” AV monografías = AV monographs, no. 121 (September 2006): 124. The disarticulated layout of the Moriyama House thus can be understood as something other than a quirky architectural caprice. Rather, it is an exercise in domestic proxemics―or an experiment in a new type of familial structure―and as such, an architectural prototype for cohabitation, with individuals living alone, yet nonetheless together.

- 1Adolf Loos, “The Poor Little Rich Man,” in Spoken into the Void: Collected Essays by Adolf Loos, 1897–1900, trans. Jane O. Newman and John H. Smith, Oppositions Books (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1982), 124–27.

- 2See, for example, Tim Benton, “Villa Savoye and the Architect’s Practice,” in Le Corbusier, ed. H. Allen Brooks (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987), 83–105; Beatriz Colomina, “A House of Ill Repute: E. 1027,” in Interiors, eds. Johanna Burton et al. (Annandale-on-Hudson: Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College; Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2012), 110–19; Alice T. Friedman, “Domestic Differences: Edith Farnsworth, Mies van der Rohe, and the Gendered Body,” in Not at Home: The Suppression of Domesticity in Modern Art and Architecture, ed. Christopher Reed (London: Thames and Hudson, 1996), 179–92; Rem Koolhaas and Bruce Mau, “Obstacles: Villa Dall’Ava, St. Cloud, Paris, France, Completed 1991,” in S, M, L, XL (New York: Monacelli Press, 1995), 132–93.

- 3Quoted in Moriyama-San, directed by Ila Bekâ and Louise Lemoine (Bordeaux: Bekâ & Partners, 2017).

- 4“Ryue Nishizawa,” GA Houses, no. 100 (August 2007): 272–73.

- 5“Moriyama House,”Lotus International, no. 163 (July 2017): 113.

- 6“Ryue Nishizawa: Moriyama House, Tokyo, Japan,” GA Houses, no. 90 (November 2005): 68; “Moriyama House, Tokyo, 2005: Office of Ryue Nishizawa,” JA: Japan Architect, no. 66 (July 2007): 24; “Ryue Nishizawa: Moriyama House,” Arquine, no. 47 (Spring 2009): 44; “Moriyama House,” a+u: Architecture and Urbanism, no. 512 (May 2013): 86–92.

- 7Rob Gregory, “Cubic Commune: Six Houses, Tokyo,” Architectural Review, no. 1326 (August 2007): 41.

- 8Ryue Nishizawa, “Moriyama House, Tokyo, Japan,” GA Houses, no. 74 (March 2003): 140; “Casa Moriyama, Ohta-Ku, Tokio, Japón = Moriyama House, Ohta-Ku, Tokyo, Japan,” El Croquis, nos. 121/122: SANAA: Kazuyo Sejima + Ryue Nishizawa, 1998–2004: Ocean of Air (Madrid: El Croquis Editorial, 2004): 364.

- 9Maggie Kinser Hohle, “Building Blocks,” Dwell 7, no. 2 (December 7, 2006): 148–55.

- 10Ibid., 148.

- 11“Moriyama cohouse: disordine apparente di progetti d’autore = Moriyama Co-House: Apparent confusion of projects by famous architects,” Lotus International, no. 132 (November 2007): 5–10.

- 12“Casa Moriyama a Tokyo = Moriyama House, Tokyo,” L’industrial delle construzioni 42, no. 404 (December 2008): 35.

- 13Emiko Takagi and Yasuhiko Saito, “Older Parents’ Loneliness and Family Relationships in Japan,” Ageing International 40, no. 4 (December 2015): 353–75; Tim Tiefenbach and Phoebe Stella Holdgrün, “Happiness through Participation in Neighborhood Associations in Japan? The Impact of Loneliness and Voluntariness,” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 26, no. 1 (February 2015): 69–97; Hiromi Taniguchi and Gayle Kaufman, “Self-Construal, Social Support, and Loneliness in Japan,” Applied Research in Quality of Life 14, no. 4 (September 2019): 941–60, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9636-x.

- 14Akira Suzuki, “Puzzle Housing,” Domus, no. 888 (January 2006): 43; “Casa Moriyama, Tokio, Japón, 2002–2005 = Moriyama House, Tokyo, Japan, 2002–2005,” AV monografías = AV monographs, no. 121 (September 2006): 124.