In this essay, cultural historian Linda Kaljundi revisits Estonian art of the late Soviet period. Looking at work from the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s from an ecocritical and environmental perspective, she argues for the necessity of taking a comparative, transnational approach in order to reach beyond the Western centric understanding of environmental art histories. Through her analysis of several artworks, Kaljundi also reveals the challenges and tensions that arise from mapping different ideas and practices entangling art and environmentalism in Estonia and the wider Central and Eastern European region.

One of the defining features of the contemporary art scene and scholarship is their attempts to write and curate global art history from ecocritical and environmental perspectives. What this process needs most is a comparative, transnational approach, and yet it faces a tradition of ecocritical art histories that have been, for a long time, produced from the perspective of the West. The same holds true for the history of environmentalism, which has mostly been defined by Western experience.

Recent and increasingly numerous attempts to challenge this tradition, that is, to provincialize the West and de-provincialize the environmental art and environmentalism of the rest of the world, also involve an ecocritical rewriting of Eastern European art histories. To borrow and extend the approach suggested by Piotr Piotrowski, to give agency to Eastern European environmental art, our attention must extend beyond inscribing it into the canonical frameworks of Western ecocritical art histories.1Piotr Piotrowski, “How to Write a History of Central-East European Art?,” Third Text 23, no. 1 (2009): 5–14. In order to construct heterogeneous, transnational histories of environmental art, we must seriously take into account the diversity of non-Western practices coming from the Global South, the indigenous peoples, and the former Socialist bloc. Reconsidering late Soviet Estonian art from an environmental perspective, this essay is positioned among broader discussions of decolonizing Eastern European art history and environmental history, both of which point to the need to abandon the norms defined by the Western canon, and give agency to the diverse practices of environmental art and activism in late-socialist Eastern Europe.2This is well demonstrated by the research and exhibition projects initiated by the Translocal Institute (http://translocal.org/), which have also entangled Eastern European art and environmentalism with the Global South.

The diversity of Eastern European artists’ engagements with the environment is well documented by Maja Fowkes in her book The Green Bloc: Neo Avant-Garde-Art and Ecology under Socialism (2015).3Maja Fowkes, The Green Bloc: Neo Avant-Garde-Art and Ecology under Socialism (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2015). Showing how, from about 1970, ecology started to figure in the neo-avant-garde practices of artists across the socialist states of Central Europe, she also highlights the difficulties of writing Eastern European history due to the nonexistence of ecocritical art history in this region. “The void around neo-avant-garde artists’ practices related to natural environment in Central European art history should not be mistaken for its nonexistence, as works dealing with the issues of nature, ecology, and natural environment were an essential part of many artists’ oeuvres.”4Ibid., 17–18.

So far, in comparison to Central and Eastern Europe, the environmental aspects of Soviet Baltic art history have gained little attention. There is, however, a growing interest in ecocritical interpretations of Baltic art, which comes from the side of research and curatorship, as well as from contemporary artistic practices, which seek new ways of creating dialogues with art history. This means digging out forgotten pieces and practices, as well as reinterpreting the better-known works from an environmental perspective. Concerning the late Soviet period, one could first and foremost seek artistic responses to the transformations of the environment and the acknowledgment of ecological crisis from the early 1970s onward.

Opening up discussion around environmental histories of Soviet Estonian art also broadens the assumption that the rise of environmentalism in Eastern Europe coincided with the perestroika period—the new politics launched by Mikhail Gorbachev in the mid-1980s that led to the fall of the Soviet Union. Indeed, environmental activism played a major role in the fall of the Soviet regime in Eastern Europe (1989–91). Movements and organizations such as Ecoglasnost in Bulgaria, the Danube circle in Hungary, the Polish Ecological Club (PKE), Sajudis in Lithuania, and the Environmental Protection Club in Latvia, among many others, were active throughout the Soviet bloc in Eastern Europe, fighting for sovereignty while opposing nuclear development, mining, hydroelectric dams, etc. In Estonia, the fight against new phosphate mines (1987) played an extremely important role in the events that culminated in the country regaining its independence in 1991.

This activism has led Western authors to treat Eastern European environmentalism as a kind of cover-up for a national independence movement. Jane I. Dawson coined the term “econationalism” to describe the perestroika–period environmental movements in the Eastern bloc and has argued that the coupling of environmentalism and the independence movement was a short-term agenda that did not lead to long-term environmental consciousness in this region. Calling it “movement surrogacy,” Dawson states that “rather than reflecting strongly held environmental principles, the [Eastern European] movements . . . were in fact often more indicative of popular demands for national sovereignty and regional self-determination.”5Jane I. Dawson, Eco-Nationalism: Anti-Nuclear Activism and National Identity in Russia, Lithuania, and Ukraine (Durham: Duke University Press, 1996), x–xi.

Perestroika-period environmentalism was indeed strongly tied to national aspirations, which makes it remarkably different from Western European environmentalism, which grew out of left-wing movements. However, limiting Eastern European environmentalism to the perestroika period, and arguing that in this region, environmental concerns were secondary, entails in itself the threat of representing environmentalism as an exclusively Western phenomenon. In contrast to this point of view, recent research has shown that environmentalism started to spread in the Eastern bloc much earlier than in the mid-1980s. For rethinking its ideas and practices, agendas and agencies, histories of visual arts and culture are good sources.

The year 1968 is a good starting point for mapping the entangledness of environmentalism across the globe. The year of the Prague Spring (the repressed anti-Soviet uprising in Czechoslovakia), the far-reaching student protests in Paris and elsewhere, and the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in the United States, it demonstrates how closely entwined the crisis of modernity was in the East and West. Despite the fact that 1968, in the Eastern bloc, is primarily associated with political repression and stagnation, it also coincides with the rise of environmental awareness. Translation of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962) in Soviet Estonia in 1968 (the Russian translation came out in 1965) is an illustration of a broader trend.

Fading Sun by Ilmar Malin (Estonian, 1924–1994) has become an iconic image of Soviet Estonian art. This 1968 painting relates to Malin’s interest in technology and science, which characterizes his paintings from the 1960s, but unlike his earlier works, it can also be associated with growing interest in the environment. Malin painted this image during his visit to Soviet Uzbekistan, which is rich in uranium and thus was a major site of Soviet nuclear testing. Hence, Malin’s apocalyptic motif of the fading sun can also be associated with a nuclear mushroom. Interpreted in this way, the painting’s representation of the soil can even be read as a manifestation of the Anthropocene avant la lettre: Malin’s depiction of the Earth resembles a scientific illustration, but not so much a soil profile as a cell structure, as if referring to the vulnerability of geology in the face of human impact.

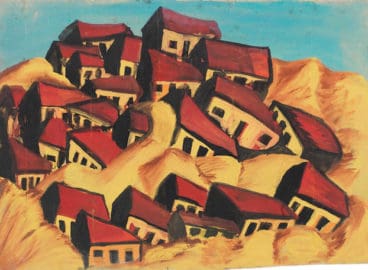

The entanglement of ecology and art around the year 1968 is most often associated with experimental art forms, as the formation of contemporary environmentalism coincided with the emergence of neo-avant-garde art. Likewise, Soviet Estonian land and performance art reveals environmental connotations. Next to this, however, the more traditional mediums, such as painting and printmaking, make visible the changing attitudes toward environmentalism, reflecting on the invasion of the natural habitat by built environments, technologies, and infrastructure. Moreover, interested in conflicts between humans and nature, writers working with painting and print media showed a remarkably diverse array of possible reactions to the ecological crisis. As a recent exhibition at the Kumu Art Museum in Tallinn demonstrates, a significant part of Estonian art from the 1970s and 1980s is focused on the dynamics between natural and man-made environments.6As recently pointed out by Eda Tuulberg and Karin Vicente, curators of the exhibition Art Is Design Is Art. See https://kumu.ekm.ee/en/syndmus/art-is-design-is-art/.

New interest in environmentalism is visible in the works of ANK ’64, an artist collective associated with the modernization of Estonian art in the post-Stalinist period. Works by the group’s female members, in particular, offer rich and, so far, largely unexplored material for an ecocritical approach. Though Kristiina Kaasik (Estonian, born 1943) has been categorized as an artist interested in aesthetic issues such as light and color, her work vividly resonates with the transforming environment, offering commentary on the changes in an elaborated though not overtly explicit manner. Kaasik’s View from the Window (1974), which depicts an environment that is idyllic and at the same time estranged, is a good example of this approach. The postcard-like view from the window seems almost to flow into the room and over the radiator. The image is organized around several contrasts, such as the pairing of a formal garden with a drab, Soviet-looking apartment, and the use of strong, artificial colors to depict the landscape. In the background, the fence between the garden and the less tame nature adds another layer, so that in total, the image represents three different kinds of environments: the apartment, the garden, and the seminatural landscape.7See Kumu Art Museum, Art Is Design Is Art, exh. booklet (Tallinn: Art Museum of Estonia—Kumu Art Museum, 2021), 28–30, https://kunstimuuseum.ekm.ee/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Kumu_Kunst-on-disain-on-kunst-saalivihik.pdf.

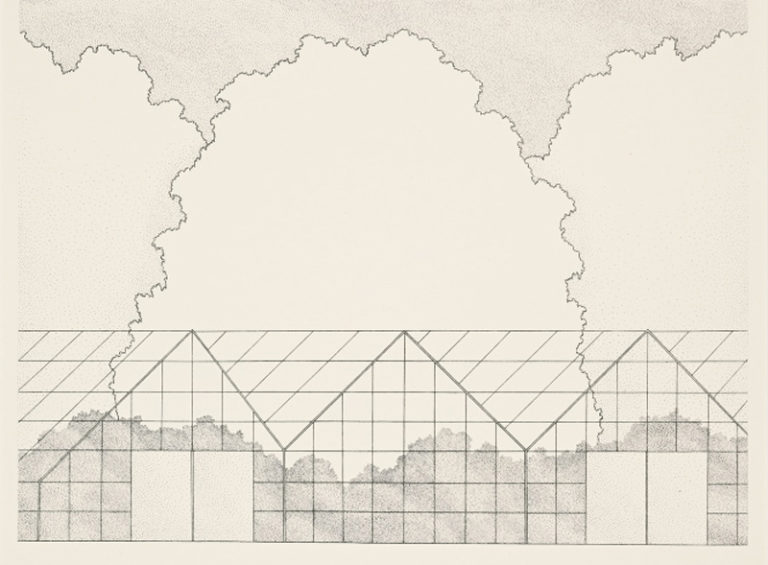

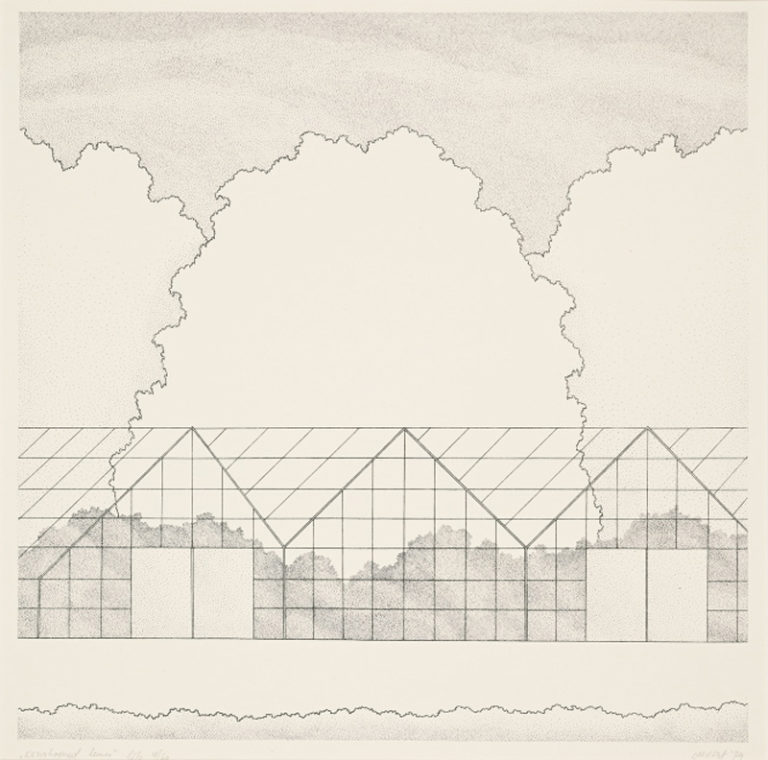

Next to her interest in parks and gardens, Kaasik developed an interest in other forms of tamed nature. Her Greenhouses (1973–74) explores the flourishing of nature in the artificial, man-made environment of an industrial greenhouse. Again, the representation of nature is estranged from nature itself through the contrast between an abundant array of tropical flowers and the technological infrastructure surrounding them. This juxtaposition elicits an uneasy feeling about what at first appears to be a pleasant view of organized nature that, upon closer look, makes one question the relationship between humans and nature. Interactions between humans and nature are addressed even more explicitly in Kaasik’s Field Melioration (1974), which addresses the effects of industrial agriculture. Much like Ilmar Malin’s Fading Sun (1968), Kaasik’s image gains new connotations in the context of the Anthropocene, as a study of the human impact on Earth’s geology and ecosystems. The larger part of the image references a scientific illustration explaining the technologies and benefits of melioration, while the background evokes the expressionist tradition of landscape painting. With its intense combination of red and yellow, and forceful-looking clouds, the background provides uneasy commentary on the cultivation of nature.

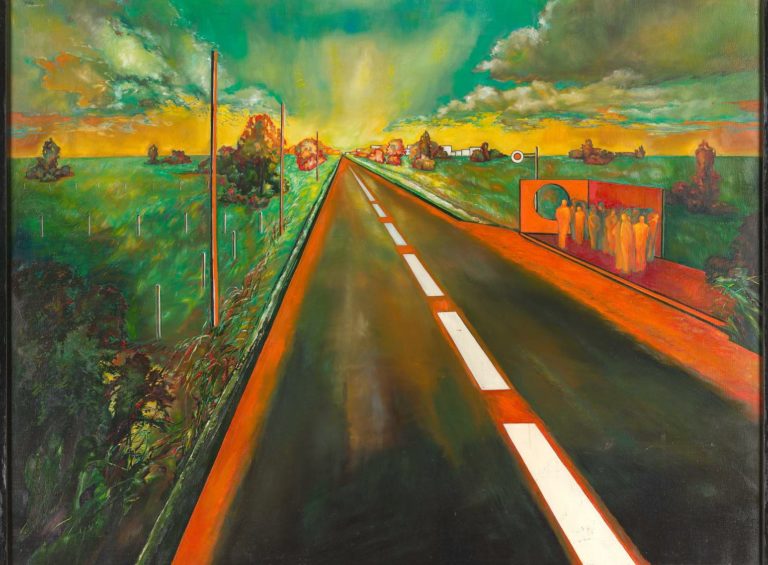

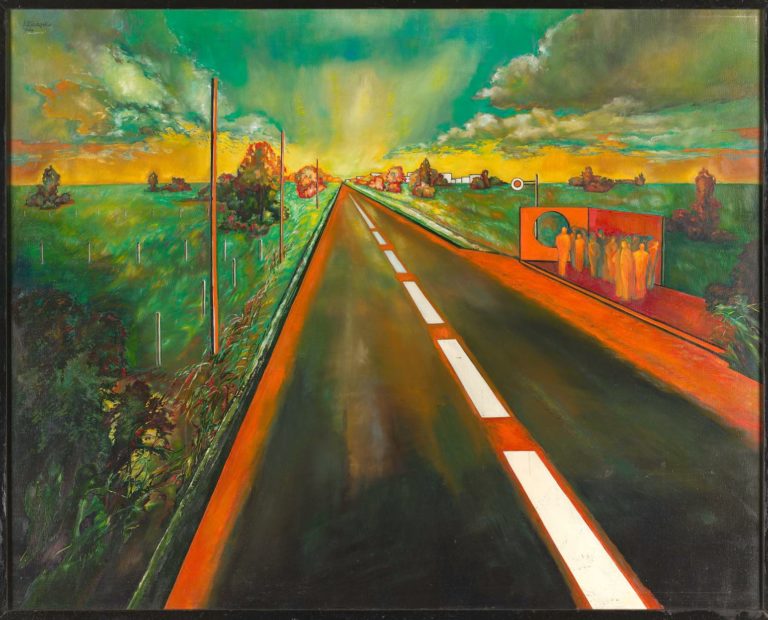

This work was shown at the young artists’ exhibition Human and Field (1974) at the Tartu Art Museum, which included another painting by Kaasik, The Road (1974), which is likewise built upon the contrast between man-made infrastructures and natural habitat. The motif of a highway cutting into nature appears frequently in the Soviet Estonian art of the 1970s and 1980s, the decades that also coincided with wider use of private cars. Though Human and Field was an institutional show organized under the auspices of the Ministry of Culture of Soviet Estonia, it demarcated a new approach to agriculture, one that differs significantly from earlier heroic representations of the transformation of natural landscapes into agricultural ones. The latter are emblematic not only of the Stalinist era,8As exemplified by numerous and well-known visualizations of the conquest of nature, such as the poster Here Was a Marsh (1950) by Siima Škop (Estonian, 1920–2016), one of the most prolific Soviet Estonian poster artists of the Stalinist era. but also of the national art of the interwar period and the Thaw. In contrast to this, many of the works shown in Human and Field problematize agricultural environments and relationships between humans and nature, demonstrating that the approach to environmentalism was not homogeneous throughout the Soviet period but rather varied considerably, especially during the 1970s and 1980s.

It is also noteworthy that the emergence of this new approach was shaped by dialogues between artists and scientists. Different artist and art student groups, including ANK ’64, organized meetings with scientists, and several of the innovative exhibitions of the 1970s took place at research institutes. Saku 73 (1973) was held in the exhibition pavilion of the Estonian Scientific Research Institute of Agriculture and Land Melioration in Saku,9It is noteworthy that this project had an impact on the aforementioned Human and Field exhibition, which was held a year later. and Harku 75 (1975) took place at the Institute of Experimental Biology. Both exhibitions have garnered attention as examples of the entanglement between artists and scientists, and yet they also demarcate the changing approach to environmentalism, which is noticeable in both the arts and scientific research of that time.

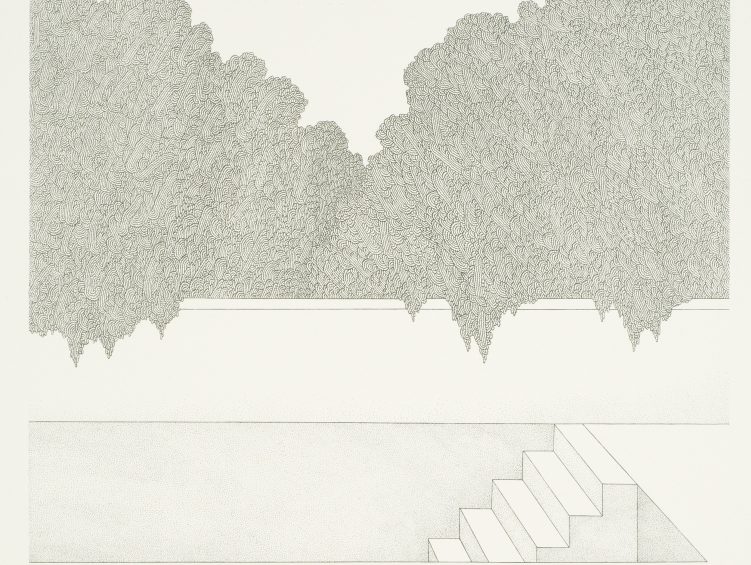

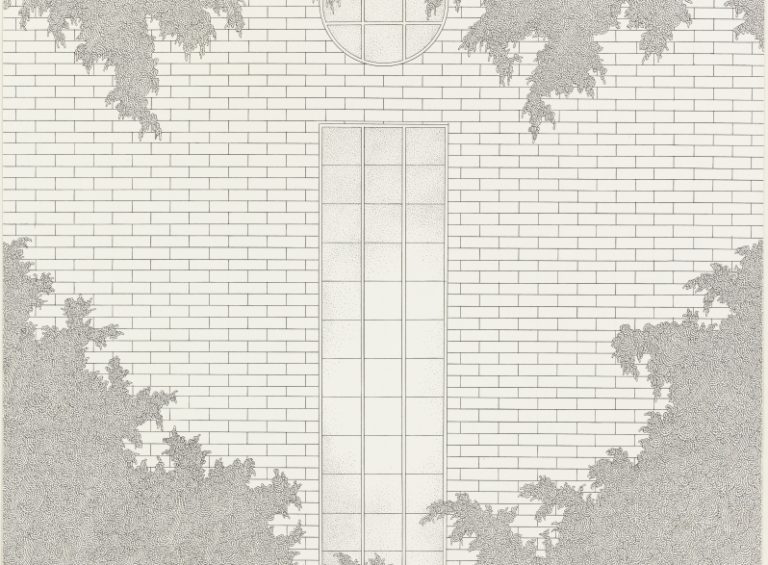

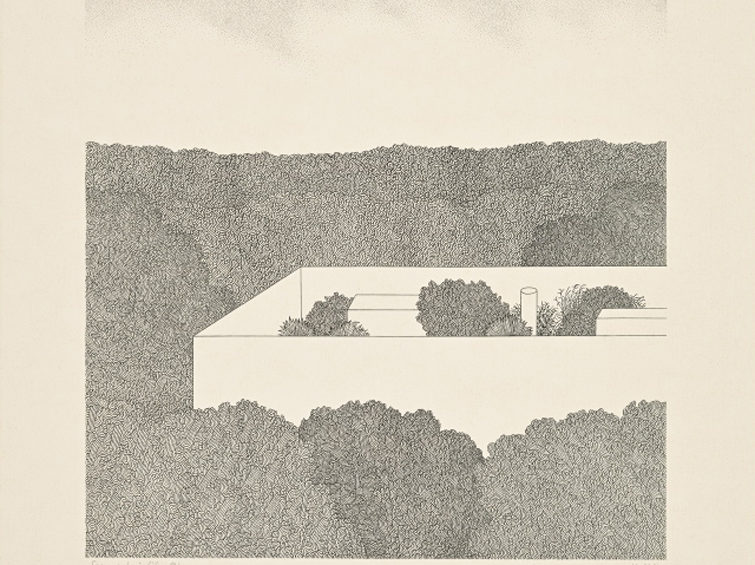

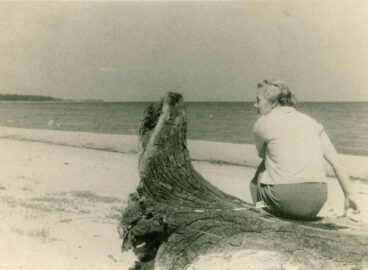

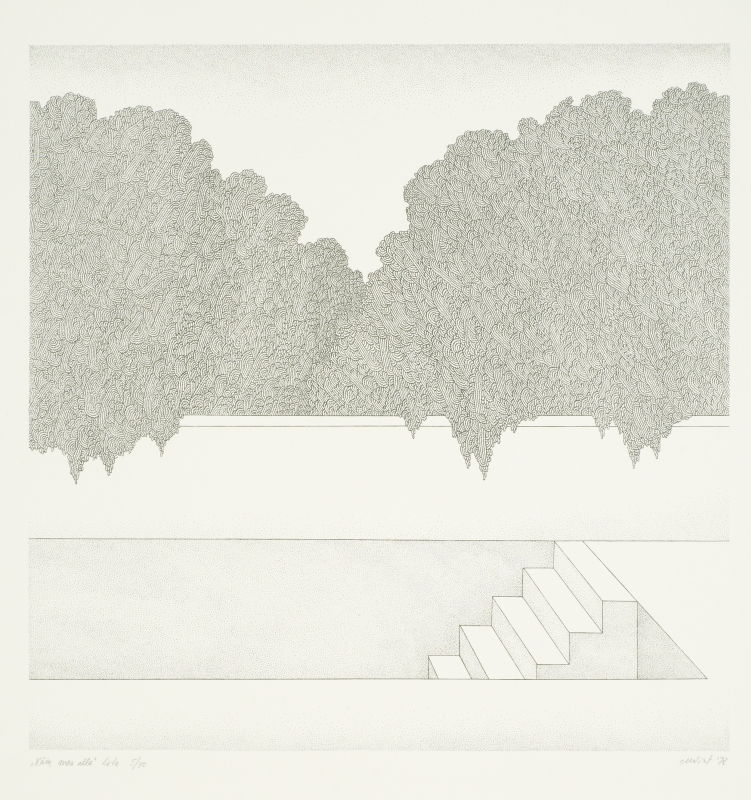

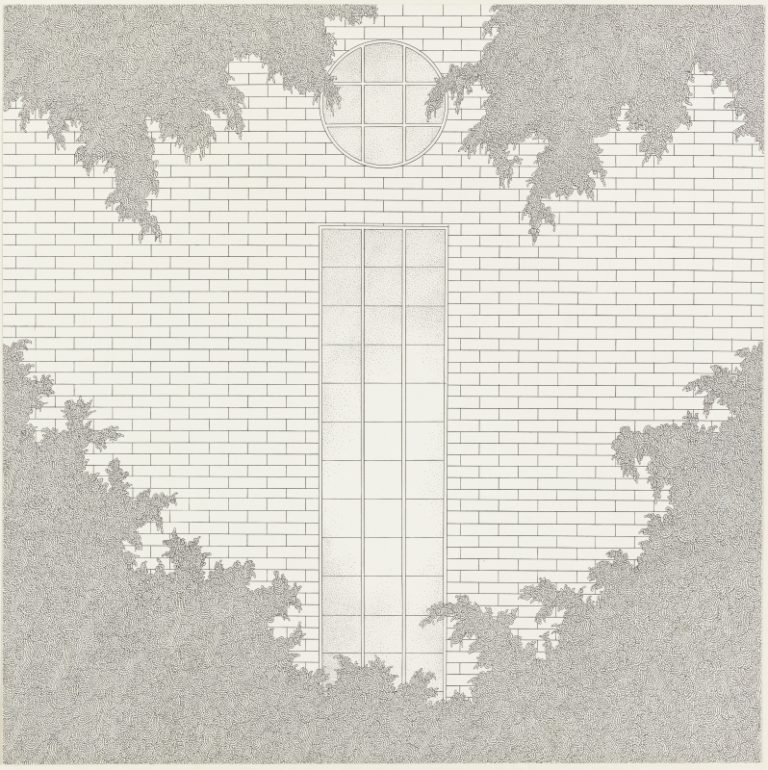

The challenges and potential of an ecocritical approach also reveal themselves well in relation to the artist Mare Vint (Estonian, 1942–2020), another female member of ANK ’64. Vint’s work of the 1970s and 1980s exemplifies the fascination with parks and gardens that was widespread among Estonian artists of the period. The turning of the artist’s gaze from wild to tamed nature can be associated with the transformation of the landscape genre, but it can also be related to a broader interest in the changing relations between natural and man-made environments. Vint’s images are not only built on the contrast between natural and artificial environments; indeed, in her pictures, even the natural habitat has been designed by humans. From an ecocritical perspective, her work explores the relations between humans and nature, addressing the possibility of a more balanced coexistence as well as the inevitability of conflicts. While her images are often interpreted as visions of the harmonious interaction between humans and nature, or the search for an ideal landscape,10“Mare Vint: In search of the ideal landscape; An express interview with the curator Francesco Tenaglia,” Arterritory.com, January 20, 2021, https://arterritory.com/en/visual_arts/topical_qa/25364-mare_vint_in_search_of_the_ideal_landscape/. in the context of an age of increasing environmental problems, these outwardly peaceful and sublime park environments also allude to hidden violence, control, and conflicts embedded in encounters between human and nature. In some of the pictures, the “tamed” flora quietly crosses the limits and barriers, giving the seemingly harmonious images an uneasy edge.

Alongside artworks addressing contemporary changes in the environment, Soviet Estonian art and culture sought solutions to the current problems stemming from the idealized past. This escapist trend reflects a broader retrospective turn, as the last decades of the USSR bore witness to the popularity of village prose, period films, heritage protection, and local history clubs. The phenomenon has been explained as the result of disillusionment in the Soviet utopian ideal, and the economic and political stagnation under the leadership of Leonid Brezhnev (1966–1982), but nonetheless, the widespread turn toward history and heritage can also be associated with a more global crisis of modernity and with a growing awareness of the ecological crisis.

Simultaneous fascination with nature and heritage conservation, as well as with folk culture and indigenous knowledge also characterizes the work of several Estonian writers. Their retrospective turn roughly coincides with the year 1968, when many of the leading figures of the 1960s experimental culture turned away from the avant-garde and began to base their artistic practices on some form of tradition: the study of Christian or Eastern religions, ancient or folk cultures, heritage, etc.

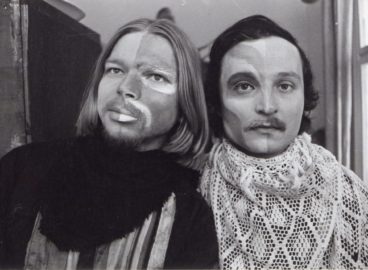

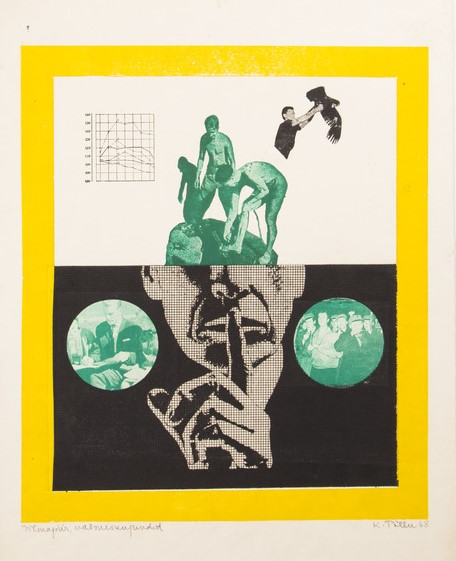

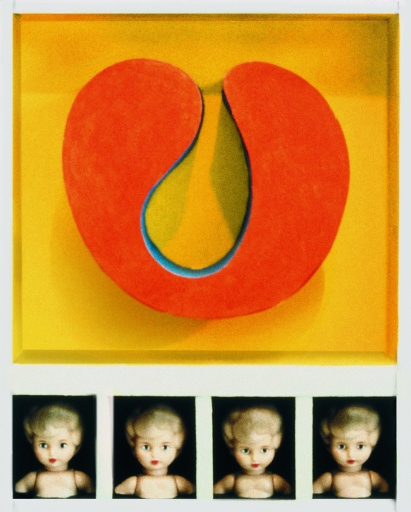

In the visual arts, the leading figure in this trend was Kaljo Põllu (Estonian, 1934–2010), who in the 1960s, was a prominent member of the Soviet Estonian avant-garde. He was among the founders of the Pop art group Visarid (1967–1972) and the head of the Tartu University art department, which promoted contemporary art and theory, as well as dialogues between artists and scientists. Põllu’s own work from the period includes assemblages, collages, and prints addressing contemporary society and culture, and appropriating elements from both Western and Soviet mass culture.

By the early 1970s, however, Põllu had devoted himself to studying the folk heritage of the Finno-Ugric peoples. Finno-Ugric languages constitute the biggest branch of the Uralic language family. The speakers of Finno-Ugric languages include Estonians, Finns, and Hungarians, but also many smaller nations of peoples living across Russia, from Karelia to Siberia. In many ways, the typical patterns of behavior of these smaller communities were still more traditional in comparison to that of the Estonians, with some elements of folk culture much better preserved.

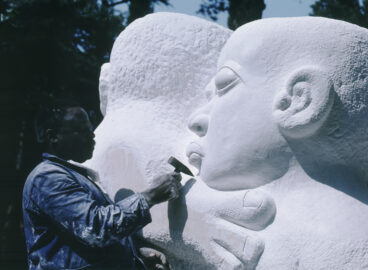

Põllu’s artistic practice became research-based, relying heavily on expeditions to small Finno-Ugric nations, as well as on cooperation with ethnographers, linguists, and other academics. Moreover, now teaching at the Estonian State Art Institute, Põllu had also initiated annual student expeditions to the Finno-Ugric territories (1978–93). The students’ preparation for these trips included meetings with specialists in folklore, linguistics, nature conservation, etc. Upon their return, they were expected to produce fieldwork reports, to systematize their visual records and other documentation (original items were never collected), and to organize related exhibitions.

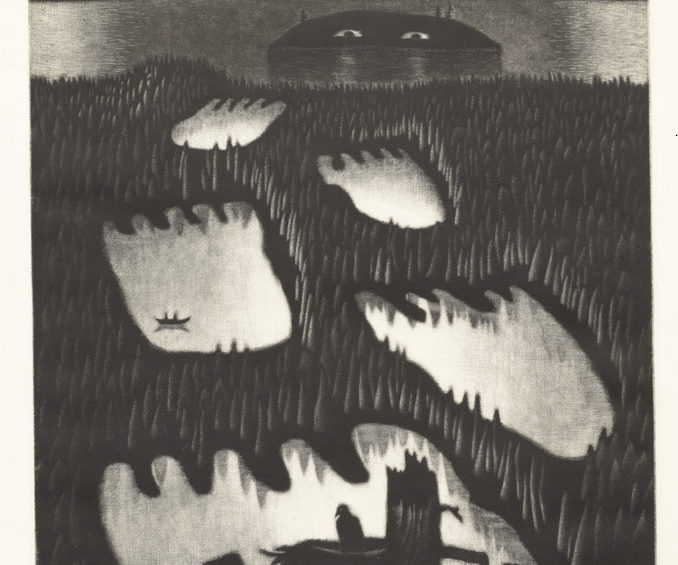

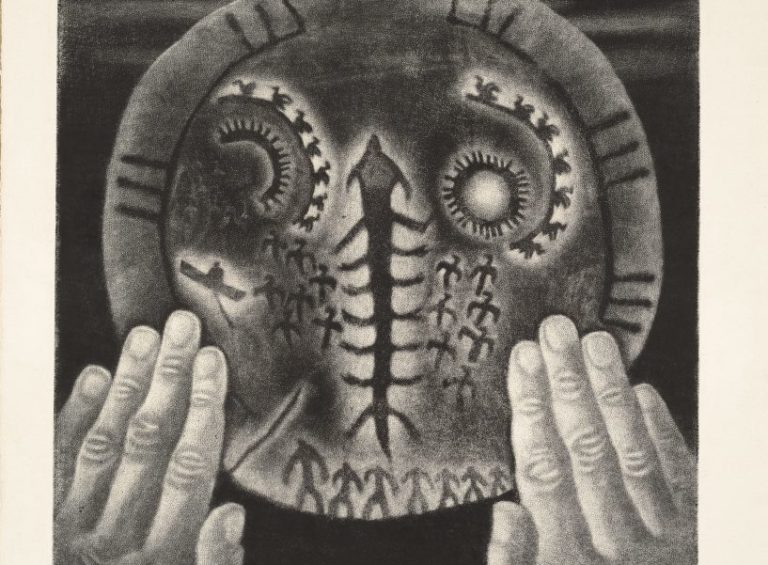

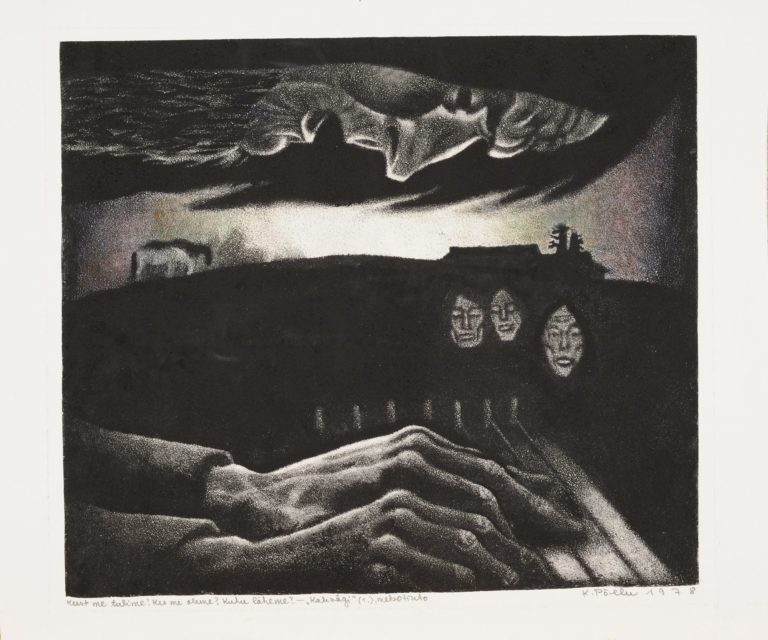

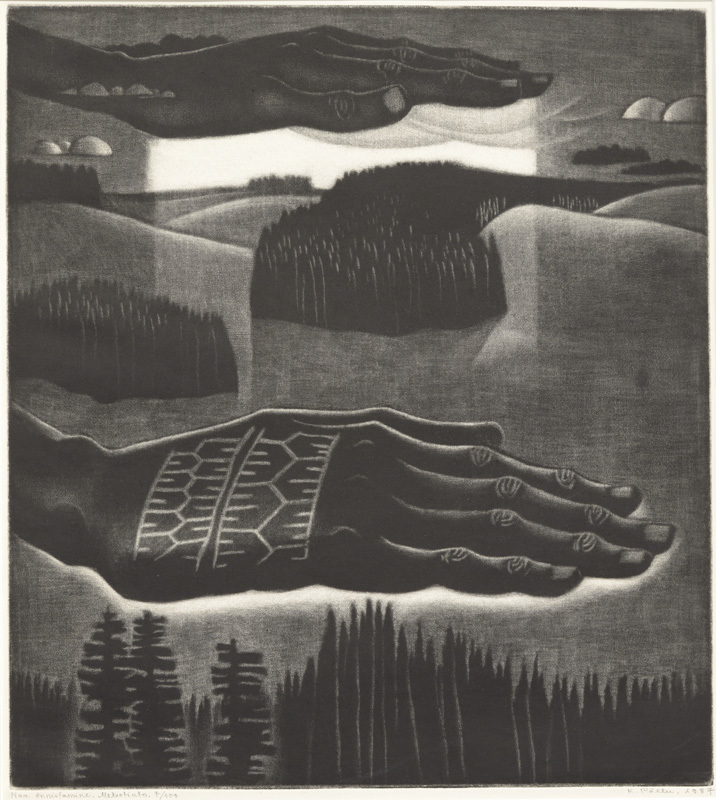

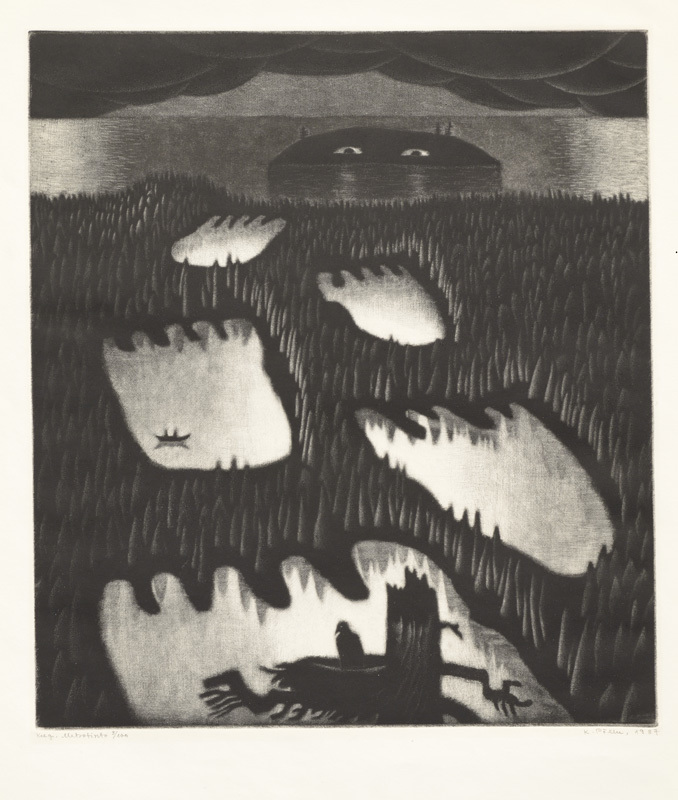

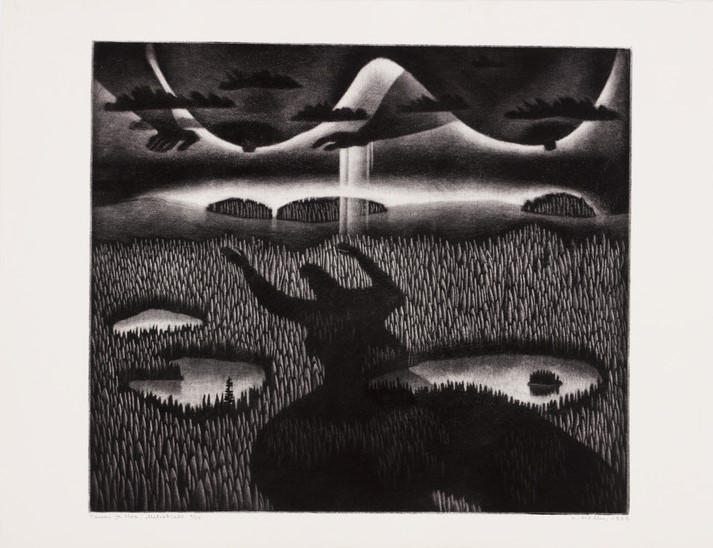

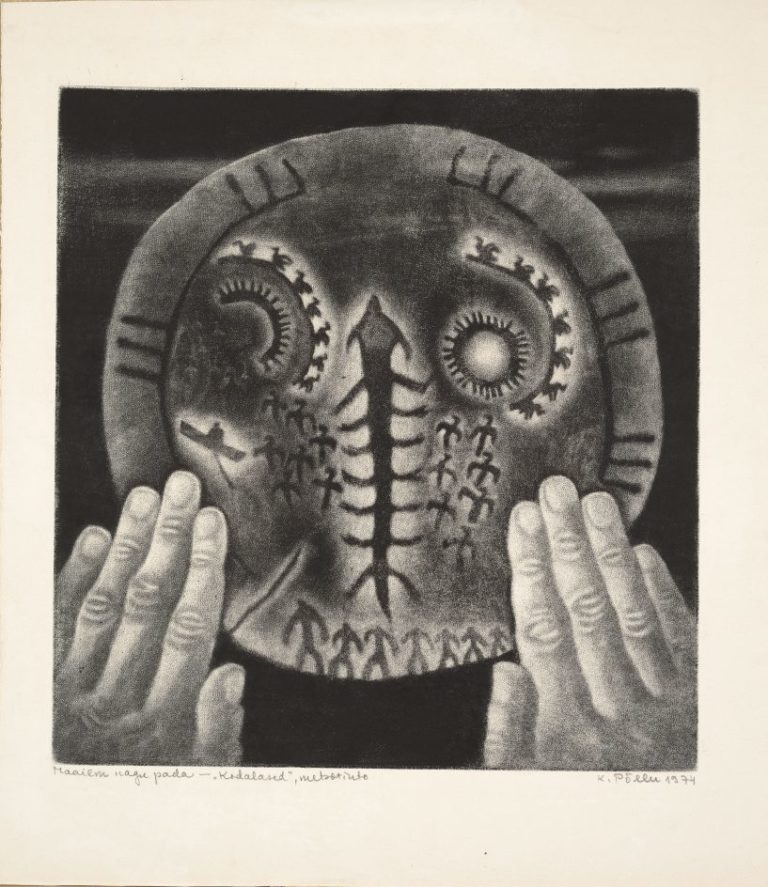

During the 1970s and 1980s, Põllu himself produced several large series based on his studies of Finno-Ugric heritage: Ancient Dwellers (1973–75; 25 works), Kali People (1978–84; 65 works), and Heaven and Earth (1987–91; 40 works). These graphic prints, mostly black-and-white mezzotints, appropriate various archetypes and symbols, and reconstruct an enigmatic vision of shared ancient heritage and its closeness to the Nordic nature. Capitalizing on animistic features, the images give agency to nature and to nonhuman animals, and yet tend to place man at the center of the universe. They also present a clear division of gender roles. Praising the cultural creativity of men, they associate women with fertility and Mother Nature. Combining concrete ethnographic details with generalization and stylization, and presenting epic time and space, Põllu’s images became very popular among the rapidly urbanizing Estonians. They were frequently exhibited, displayed on the walls of cultural and other institutions, reproduced widely in print media, and re-mediated in various other forms of culture, etc.

Põllu’s works also contributed to a wider acceptance of Finno-Ugric identity among Estonians, which prior to the late Soviet period, was never a dominant element in the Estonian ethos. Now, however, the idea of Estonians as Finno-Ugrians was being popularized by a number of Estonian artists, performers, writers, musicians, etc.11Among others, those almost exclusively male cultural figures included Lennart Meri (1929–2006), who would later become the second president of Estonia. In the 1970s and 1980s, he authored a series of popular books and documentary films on the indigenous Finno-Ugric roots of the Estonians. The success of this Finno-Ugric revival was partly based on its promoters’ skillful combination of the roles of artists and scientists. They presented their work as research-based, although they took significant artistic license in their interpretations of history and heritage. This freedom of expression led to conflicts with academic scholars, but appealed to the wider audience and resulted in an identity pattern that is still dominant today.

In a global context, the revival of Finno-Ugric identity can be associated with the significance of natives in environmental, as well as decolonizing movements. In the 1970s, native peoples of the United States as well as other indigenous groups became icons of environmentalism. Idealization of their close and harmonious relations with nature holds an important place in the works of Kaljo Põllu, who also cooperated closely with the Estonian Nature Protection Society. Just like the other cultural figures behind the Finno-Ugric revival, Põllu linked environmentalism closely with a critique of European cultural domination. This connection fit well with the Soviet critique of Western imperialism, and yet has deeper roots in Estonia, which had been colonized and dominated by German-speaking elites since the thirteenth century. Thus, the idea of going back to the Finno-Ugric roots had decolonial connotations, as it is associated with abandoning the later colonial and Germanic cultural layers.

Yet basing Estonian identity on being Finno-Ugric was far from unproblematic, as it in many ways reflects the desire to be white and indigenous at the same time. Põllu’s works can in some ways be compared to that of native artists of the time. To a certain extent, Põllu and his contemporaries identified themselves and their whole nation with the Finno-Ugric peoples. And still their works are significantly hybrid. On the one hand, Põllu and others go beyond the perspective of the Westerner, who merely records indigenous culture. On the other, they do not entirely position themselves as indigenous artists. At any time, Põllu, and his contemporaries could remain at a safe distance, maintaining their position as the more civilized, modernized brothers to their Siberian siblings. From an environmental perspective, it is noteworthy that the Finno-Ugric turn in Estonian culture does not comment on the effects of increasing oil and gas production in the Finno-Ugric territories, although open criticism would have been hard (but not entirely unimaginable) in the Soviet context.

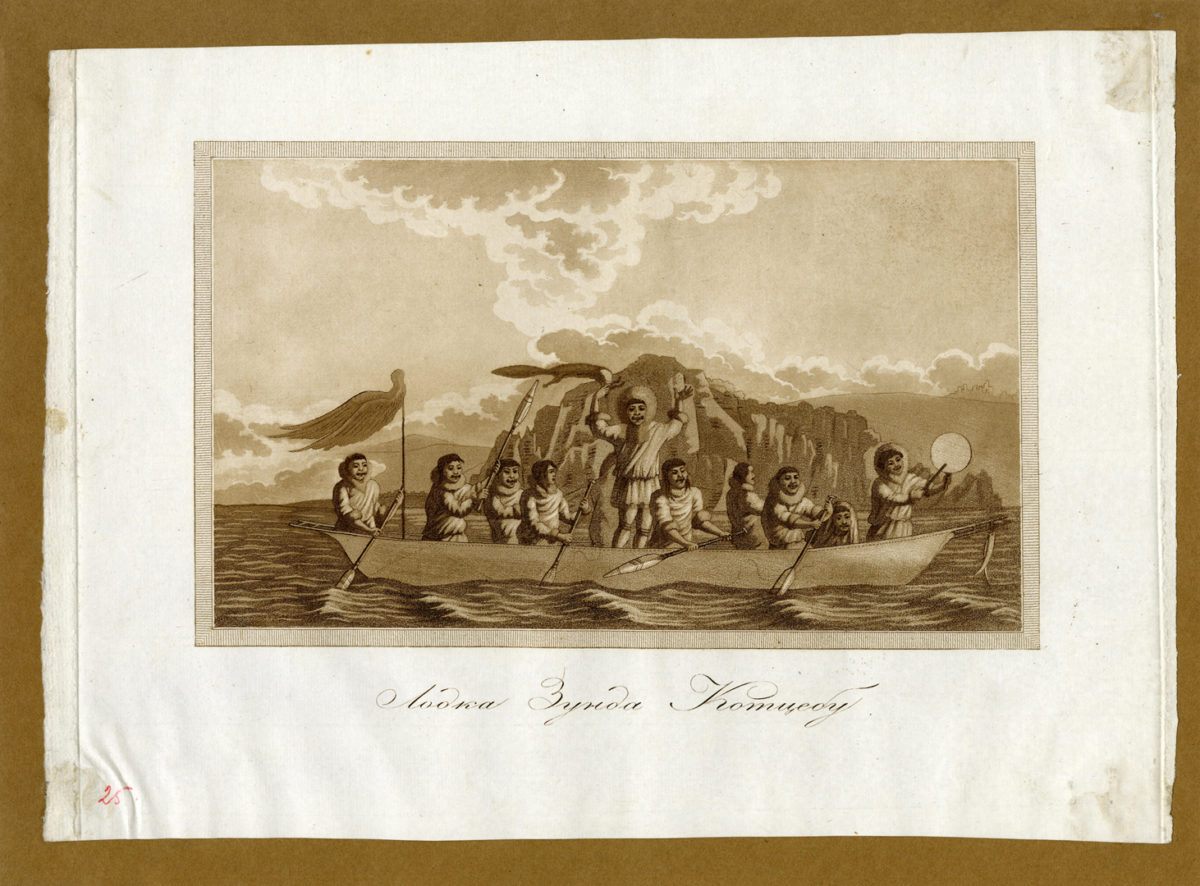

What Põllu and his contemporaries did share with the decolonizing indigenous groups was a complicated relationship with the images created by the colonizers. Although Põllu and others valued Finno-Ugric folk culture because of its authenticity, it was hard for them to avoid the adaptation of old colonial stereotypes. Borealist imagery of the Finno-Ugric and Samoyedic peoples was created by the Russian imperial and Baltic German scholars in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, capitalizing on the former’s close ties to nature.12This relationship was explored in the exhibition The Conqueror’s Eye: Lisa Reihana’s In Pursuit of Venus (2019), curated by Linda Kaljundi, Eha Komissarov and Kadi Polli. See Kumu Art Museum, The Conqueror’s Eye: Lisa Reihana’s In Pursuit of Venus, exh. booklet (Tallinn: Art Museum of Estonia – Kumu Art Museum, 2019), https://kunstimuuseum.ekm.ee/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/WEB_Vallutaja_pilk_ENG_buklet.pdf. Turning the native Finno-Ugric peoples into icons of authenticity and environmentalism, Estonian artists, writers, filmmakers, etc. appropriated many elements from age-old colonial representations of Nordic indigenous peoples. The appearance of such hybrid images also reveals the making of Finno-Ugric identity to be a decolonizing process, whereby the colonized cannot entirely avoid the adaptation of the image created by the colonizer—both fighting against it and imitating it.

The association of nature with national identity in Estonia remains strong today, but ranges from diverse activist circles to conservative politicians and the neoliberal version of eco-nationalism that brands Estonia as an eco-digital nation.13Epp Annus, “A Post-Soviet Eco-Digital Nation? Metonymic Processes of Nation-Building and Estonia’s High-Tech Dreams in the 2010s, East European Politics and Societies and Cultures, published online October 8, 2020, https:/doi.org/10.1177/0888325420958138. Yet it seems crucial to highlight the diversity that reveals itself in the Soviet Estonian art and environmentalism of the 1970s and 1980s. The mapping of diverse approaches and ideas, practices, and reactions, is important in the writing of environmental art history and environmental history as such, which also needs to bring together and consider intellectual formations that are somewhat in tension with each other.14Dipesh Chakrabarty, The Climate of History in a Planetary Age (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2021). This reality is especially significant in the increasingly polarized societies in Eastern Europe and elsewhere today.

*This and all the further images in this text are from the database Muis.ee.

- 1Piotr Piotrowski, “How to Write a History of Central-East European Art?,” Third Text 23, no. 1 (2009): 5–14.

- 2This is well demonstrated by the research and exhibition projects initiated by the Translocal Institute (http://translocal.org/), which have also entangled Eastern European art and environmentalism with the Global South.

- 3Maja Fowkes, The Green Bloc: Neo Avant-Garde-Art and Ecology under Socialism (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2015).

- 4Ibid., 17–18.

- 5Jane I. Dawson, Eco-Nationalism: Anti-Nuclear Activism and National Identity in Russia, Lithuania, and Ukraine (Durham: Duke University Press, 1996), x–xi.

- 6As recently pointed out by Eda Tuulberg and Karin Vicente, curators of the exhibition Art Is Design Is Art. See https://kumu.ekm.ee/en/syndmus/art-is-design-is-art/.

- 7See Kumu Art Museum, Art Is Design Is Art, exh. booklet (Tallinn: Art Museum of Estonia—Kumu Art Museum, 2021), 28–30, https://kunstimuuseum.ekm.ee/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Kumu_Kunst-on-disain-on-kunst-saalivihik.pdf.

- 8As exemplified by numerous and well-known visualizations of the conquest of nature, such as the poster Here Was a Marsh (1950) by Siima Škop (Estonian, 1920–2016), one of the most prolific Soviet Estonian poster artists of the Stalinist era.

- 9It is noteworthy that this project had an impact on the aforementioned Human and Field exhibition, which was held a year later.

- 10“Mare Vint: In search of the ideal landscape; An express interview with the curator Francesco Tenaglia,” Arterritory.com, January 20, 2021, https://arterritory.com/en/visual_arts/topical_qa/25364-mare_vint_in_search_of_the_ideal_landscape/.

- 11Among others, those almost exclusively male cultural figures included Lennart Meri (1929–2006), who would later become the second president of Estonia. In the 1970s and 1980s, he authored a series of popular books and documentary films on the indigenous Finno-Ugric roots of the Estonians.

- 12This relationship was explored in the exhibition The Conqueror’s Eye: Lisa Reihana’s In Pursuit of Venus (2019), curated by Linda Kaljundi, Eha Komissarov and Kadi Polli. See Kumu Art Museum, The Conqueror’s Eye: Lisa Reihana’s In Pursuit of Venus, exh. booklet (Tallinn: Art Museum of Estonia – Kumu Art Museum, 2019), https://kunstimuuseum.ekm.ee/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/WEB_Vallutaja_pilk_ENG_buklet.pdf.

- 13Epp Annus, “A Post-Soviet Eco-Digital Nation? Metonymic Processes of Nation-Building and Estonia’s High-Tech Dreams in the 2010s, East European Politics and Societies and Cultures, published online October 8, 2020, https:/doi.org/10.1177/0888325420958138.

- 14Dipesh Chakrabarty, The Climate of History in a Planetary Age (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2021).