The annual Asilah Cultural Moussem, an international festival held in northern Morocco, was cofounded in 1978 by Mohamed Benaïssa and Mohamed Melehi in collaboration with Toni Maraini and Al Muhit Cultural Association. It served as a significant postcolonial cultural platform, involving activists from the Casablanca Art School and artists from Africa, the Arab world, Asia, Europe, and the Americas. The festival featured outdoor exhibitions, murals, visual art workshops, theater, music, and social and cultural programs aimed at rehabilitating the neglected city of Asilah and integrating art into social progress and daily life. The Asilah Cultural Moussem is still ongoing to this day.

Morad Montazami: Toni, to start the conversation, can you tell us how the idea of creating a festival of murals in Asilah—literally on the city’s walls (fig. 1)—came to you and Mohamed Melehi?

Toni Maraini: Firstly, I would like to mention that Mohamed Benaïssa was with us from the outset. Melehi and Benaïssa were born in Asilah, and our mutual friendship had blossomed many years before under various circumstances. Back when we were teaching at the Casablanca Art School in the 1960s, Melehi and I frequently traveled to Asilah, where we met Benaïssa. At that time, Asilah’s old medina was in poor condition; walls were deteriorating, many houses were abandoned, and the streets were quite dirty. When we got together with Benaïssa, we often discussed how we could contribute to the community’s cultural and economic development. Our goal was to enhance Asilah’s living standards, and for this, we thought about creating a festival. However, instead of calling it a “festival,” we decided to call it a “moussem,” the term traditionally used in Morocco for local festivities organized by the community. Thus, the Asilah Moussem needed to be community-driven from the outset. This is how the concept of a moussem emerged. Fortunately, there were elections during this time, and both Benaïssa and Melehi had campaigned for local office. Their active involvement in various community projects sparked enthusiasm among the residents, and they were voted in: Benaïssa was elected mayor, which was a significant milestone for Asilah’s political landscape, and Melehi was elected member of the municipality and took on a prominent cultural role, creating a group called Al Muhit Cultural Association. This cultural association represented a fresh start, marking a new chapter in the city’s history. Concurrently, the Ministry of Culture provided funding to restore the city’s walls and its long-neglected houses. This was when the vision of visible walls took form.

MM: This photo conveys a sense of how artists organized and assigned the walls for painting.

TM: Take a look at the state of the walls in this image (fig. 2). The house you see in the background was abandoned. Fortunately, we had numerous friends who were artists. We forged these connections through our involvement in the Casablanca Art School and through various other activities,1Toni Maraini and Mohamed Melehi joined the teaching staff of the Casablanca Art School in 1964 and remained there until 1969. Maraini taught courses on modern art history and authored manifestos and theoretical essays related to the activities of the artistic group, collaborating with artists such as Farid Belkahia, Mohammed Chabâa, and Mohamed Melehi. Melehi offered painting courses with an experimental approach that included collage techniques. In addition to these initiatives, he established the school’s photographic studio and workshop. Both Maraini and Melehi played significant roles in the contemporary rediscovery and reevaluation of popular African arts and local Amazigh arts and crafts. including organizing a series of public outdoor exhibitions—Présence Plastique—on the streets of Marrakech and Casablanca.2The Présence plastique (Plastic Presence) outdoor public exhibition series was led by the core group of the Casablanca Art School (Farid Belkahia, Mohammed Chabâa, Toni Maraini, and Mohamed Melehi) joined by three other artists (Mustapha Hafid, Mohamed Hamidi, and Mohamed Ataallah) who organized a public display of their paintings on the Jemaa el-Fna Square in Marrakech (May 1969) and the 16 November Square in Casablanca (June 1969) as well as in different high schools in Casablanca in 1971, with the aim of creating a public platform and pedagogy around modern and contemporary art within Moroccan society. These artists participated with great dedication. In figure 2, we see them walking around the medina, deliberating on which area to tackle.

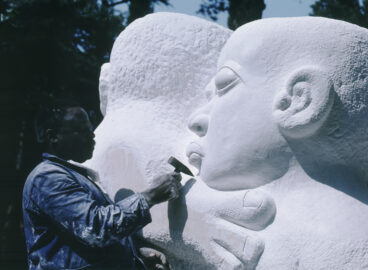

Artists were organized into six groups, with each one focusing on a specific location. The walls would initially be painted white, and then each artist would create a composition with the assistance of local young people. Everyone collaborated regardless of gender and age. Take, for example, this mural by Mohammed Chabâa (fig. 3; see also fig. 1). In the photograph, you can see Chabâa himself, but there is also someone assisting him. The wall was painted white, and the streets have been cleaned.

MM: Toni, you pointed out your experience with collaborative methodologies, dating back to the renowned Présence Plastique outdoor exhibition series held in Marrakech and Casablanca in 1969. Therefore, by the time of the Asilah moussem, roughly a decade later, you all had had experience with public space exhibitions. Could you elaborate on the specificity of the Asilah Cultural Moussem and the unique interactions that it fostered between artists and the local community?

TM: First of all, it differed in that in Jemaa el-Fna Square, paintings were hung on the walls of a large, unique public space. Here in Asilah, murals were created on the walls in various corners and city streets. The enthusiasm of the people was enormous, as they would pitch in to help with the painting.

MM: Did local people spontaneously join the mural collaboration, or had you planned for these murals to involve the local community?

TM: As muralists, we naturally considered the principles of street art. It needs to be in public spaces, contributing to urban development, and involving people’s participation. This is why, when working with Benaïssa on the concept of the Moussem, Melehi and I proposed a special art and culture project with three components: workshops, exhibitions, and street art.

MM: And can you tell us about the role of the local inhabitants, especially women? When we examine some of the photographs taken by you and Melehi, we can see many women collaborating on the murals.

TM: Yes, many female students had gathered to create their walls, and older women would come around to look, offering suggestions and help (fig. 4). That was indeed socially important. It sparked interest and friendship and, moreover, it reflected the female community’s desire to turn to more modern habits and experiences, changing from what Asilah was and engaging for better local conditions.

MM: Yes, as you say, apparently the local inhabitants understood the project, and there was some sort of synergy between the project, the city’s state, and how local people responded with enthusiasm and positivity to the Moussem, which brings me to my next question: Was Asilah already a tourist destination in 1978, or did it become one after the creation of the Moussem?

TM: Before the 1970s elections, Asilah was in such poor condition that it only drew a transient crowd—people who would briefly visit and then leave. The restaurants were shut down, and there was nothing to offer visitors. However, after 1978, Asilah’s economic situation improved significantly as shops started to open. Artisans, both men and women, would now sell their products, like rugs and ceramics. The weekly market became a gathering place for people from the countryside to sell their goods—vegetables, tomatoes, and many other products from nearby farms and fields. It was always crowded and very animated. The streets were cleaned, and many shops and houses reopened. Two traditional restaurants (one owned by a woman) opened as well. All of this attracted tourists, who came to see the murals. A museum was also established in the ancient Portuguese Al-Kasbah Tower, where some exhibitions were organized. These significant changes encouraged thoughtful tourism—tourism that pauses, observes, and values. Eventually, as people’s income improved, local families found it easier to send their children to school.

MM: Let’s discuss the workshops that featured so many key artists, especially in such a cosmopolitan environment. Can you tell us how these workshops were organized? I know, for instance, that the printmaking workshop was very significant.

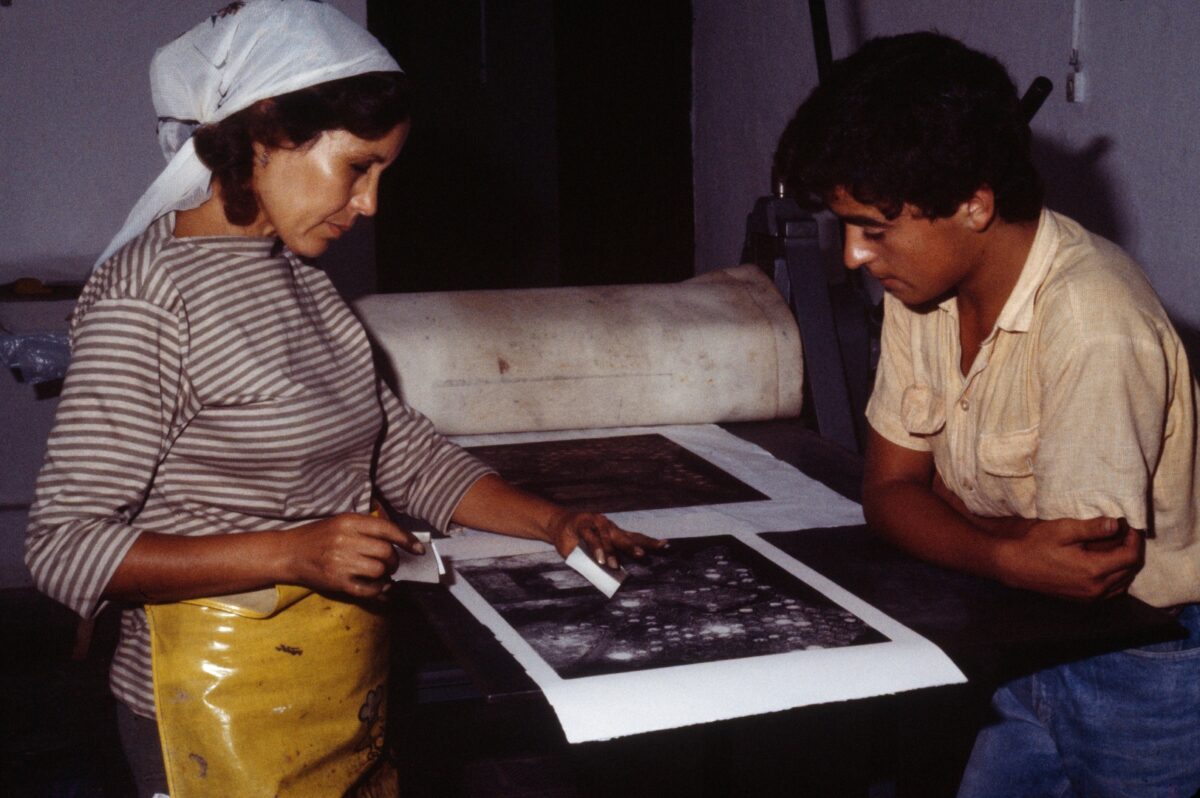

TM: There was a painting workshop that welcomed artists of different nationalities and offered lessons to the youth from the city, but the printmaking workshop (fig. 5) was particularly significant, thanks to three outstanding artists, Mohammad Omar Khalil, Krishna Reddy and Robert Blackburn, who were experts in the field and supervised the workshop activities for several years. They coordinated all aspects, secured all the printing machines, etc. The printmaking workshop was the first of its kind in Morocco. Several artists, such as Farid Belkahia and Malika Agueznay (fig. 6), came to learn how to print their own works on paper, and over the years, they engaged in teaching these techniques to local students.

MM: How and when did you and Melehi connect with Mohammad Omar Khalil, Krishna Reddy and Robert Blackburn?

TM: We became acquainted with them during our stay in New York from 1962 to 1964. Melehi had been awarded a Rockefeller Foundation Fellowship, and I had been given a scholarship to Smith College. While in New York, visiting exhibitions and participating in cultural meetings, we became good friends with several artists.

MM: So you actually knew these artists for almost 18 years before inviting them to Asilah. That’s impressive!

TM: In those years, we traveled to New York several times, and met them again, and we became friends. The Moussem was a good occasion to invite them to Morocco. Given our collaborations on projects associated with the Casablanca Art School and international exhibitions or meetings, we also traveled to Baghdad, Lebanon, Tunis, Algiers, France, and Spain, and met many other artists. It was a fascinating cosmopolitan time that fostered numerous international, cultural, and artistic connections. Unlike today, there was a positive atmosphere, one characterized by a strong desire to collaborate in every direction—north, south, east, and west.

MM: It’s evident that our current fascination with the 1960s and 1970s, along with the broader postcolonial networks and solidarities, indicates we are facing challenges today. This suggests that our solidarities and networks clearly have limitations, and we need to draw our inspiration from that era.

TM: Exactly. There were no borders at that moment.

MM: Could you remind us if international artists were invited to the first edition, or if the 1978 edition primarily featured Moroccan artists—with international artists being invited starting from the second edition?

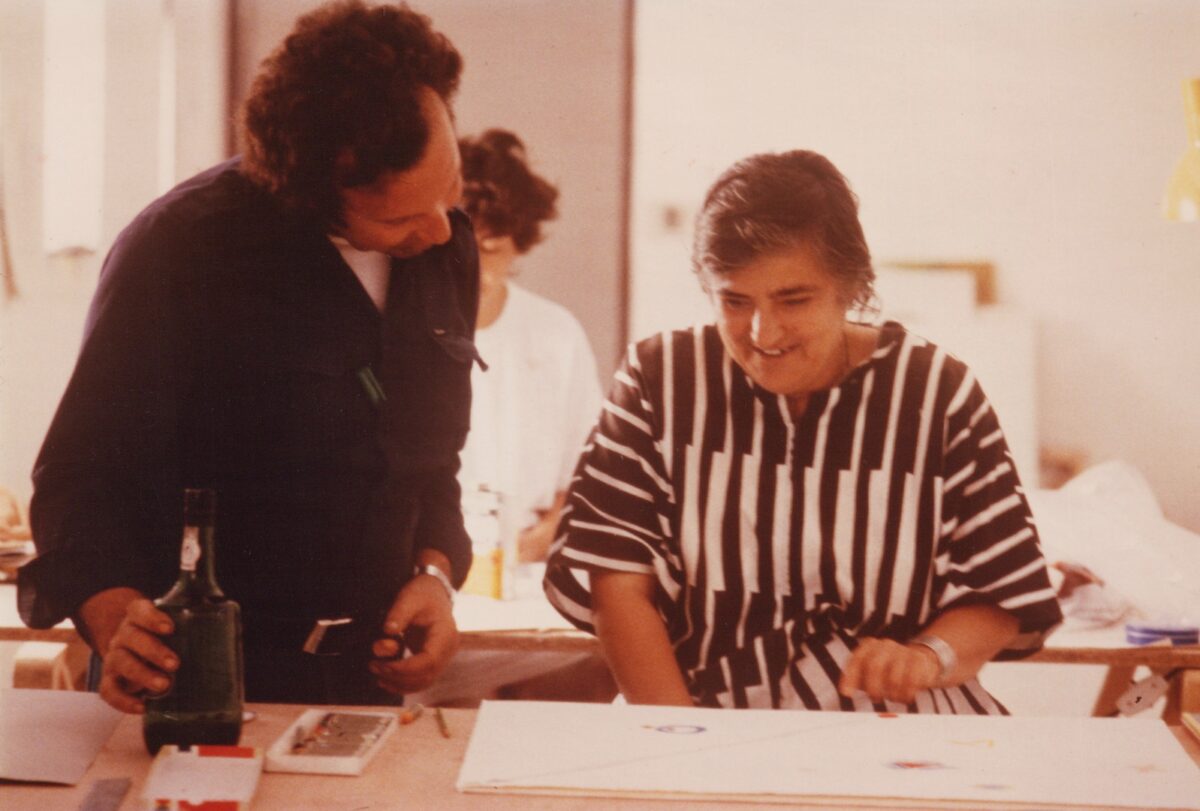

TM: Since our initial concept was to conduct local activities with an international approach, fostering connections between the north and south, east and west, and of course, Africa, the first edition was absolutely international (fig. 7) . . .

MM: For example, if I recall correctly, the first time you met Etel Adnan was around the time of the First Biennale of Arab Art in Baghdad in 1974. Four years later, she came to Asilah. I mean, there was a very strong dialogue and an artistic friendship between you and Adnan, as you even translated some of her poems into Italian.

TM: Yes, over the years, I translated and published three of her books and several poems in Italy. I also wrote for the catalogues of a couple of her exhibitions. As you say, I met Etel Adnan in 1974 at the Baghdad biennale, which I attended with Melehi and Belkahia. Since she told us she wanted to visit Morocco, we invited her in 1978; she visited Asilah, traveled around, had an exhibition in Rabat, and then in 1979, came again to participate in the Moussem painting workshop.

MM: There were printmaking workshops, painting workshops, and ceramics workshops, right? Who were the main participants practicing in these workshops? Were they mostly young Moroccan artists from Asilah? Obviously, many incredible artists came together, like Etel Adnan, Mona Saudi, and Malika Agueznay—all the ones we mentioned. But who were the workshop practitioners? Were they young people from Asilah or even youth from other Moroccan cities coming to Asilah in the summer?

TM: The workshops were open to everyone. Some of the artists invited would be responsible for organizing workshops and teaching programs. Artists from many countries would work at the workshops, as did young people from Asilah, including some who came from Tangiers or Rabat. Workshops were a great place for artistic convergences, not only for painting, sculpture, and ceramics but also for learning printmaking, as it was, at that time, the only place to learn it in Morocco (fig. 8).

MM: So this was a poster exhibition (fig. 9), right? Can you tell us if there was a direct relationship between the printmaking workshop and such displays? Were the works on display there mainly by artists who took part in the workshops, or were there other printmakers?

TM: This poster exhibition was held with works made for the occasion by the artists participating to the painting and printmaking workshops. The wide exhibition space was once an abandoned factory that had been restored. It became a very important municipal gallery called “Al-Qasaba,” where many exhibitions have been held over the years.

MM: Were you the curator of this exhibition?

TM: The art exhibitions were curated collaboratively! Certainly, Melehi and I would participate in their conception, yet much of the work was made possible thanks to the collaboration with the new local association called “Al Muhit,” created by Melehi and Benaïssa with the enthusiastic participation of other friends and people from Asilah, Tangier, and Rabat.

It is important to remember that during the Moussem there were not only the workshops and exhibitions, but also many other different projects—conferences, music and theater rehearsals, film screenings, and all the while street art activities. Every day, women and men worked hard and collectively to make all this happen. This is what the Moussem was intended to convey: a collaborative effort that showcased the dynamic enthusiasm of the community.

MM: OK, I get it. So there was never really one person, for example, responsible for the poster exhibitions; it was always a collective effort.

TM: As a newly elected member of the city council, Melehi was responsible for cultural activities. He would work from morning to evening on everything related to the arts, and I would help—but, as I said, without the participation of work groups and the great collective force, it would have been impossible to realize these cultural, artistic, and social projects concretely.

MM: It’s quite clear that you and Melehi were significant driving forces, albeit within a collective framework. Additionally, you both stood out as key figures in fostering connectivity, effectively bringing together artists from diverse backgrounds and countries in Asilah.

In the children’s workshop, you played a crucial role. I know you always tell me not to exaggerate your contributions, but in this case, it was definitely you who raised the idea of creating workshops for children. I’m aware that your experience with children and art pedagogy goes back further, as you had already been involved in art therapy, even in schools in Casablanca in the early 1970s. Can you share how the concept of children’s workshops and art pedagogy became so meaningful for you, and how you later implemented it in Asilah?

TM: When I was teaching at the Casablanca Art School, I also wanted to do something for younger audiences and the public schools. In 1976, I was asked by the headmistress of the Ibn Abbad school—a public school in a neglected neighborhood in Casablanca—to organize a free art workshop there. It turned out to be a great experience not only for me but also for the students, who joined with enthusiasm and, in many cases, did much better in their studies and their behavior as a result. That prompted me to study art therapy. In fact, every art historian knows that art serves as a form of therapy. I had a good friend, the psychiatrist Abdallah Ziou Ziou, who encouraged me and with whom I often exchanged ideas. Then, I had the opportunity in 1980 to open an art therapy workshop at the Children’s Hospital Ibn Rochd in Casablanca for two years. That was a great responsibility but also a fantastic experience.

MM: Did you implement the children’s workshop beginning with the first edition of the Moussem?

TM: Yes, since the very beginning . . . and I didn’t want the artists to join and teach . . . there was nothing to teach. The children would teach the artists (fig. 10)!

MM: The workshop’s approach was that we shouldn’t try to teach them anything; rather, they can teach us something.

TM: Certainly! They have valuable lessons to teach us and share. The issue was that at their school, students were asked to copy images, and instead of letting them express themselves, the children would have their drawings severely judged and corrected. During the first week, the first month, and the very first years of the Moussem, the doors of my workshop—which was organized in an open space between the street and the garden of the Raissouni Palace—were wide open, welcoming children and teenagers, boys and girls, from the streets and the neighborhoods around. They came, some from very poor backgrounds, others not. They came in, stayed, and played. Initially, there were approximately 20 children, and within two years, the number grew to around 200, possibly even 250 (fig. 11).

MM: Many of these children seem to have attended the workshop consistently over the years. Some of them you followed over the years; it wasn’t a one-time meeting. I believe you worked with several of them for many years, which implies that you saw some of them grow up, correct?

TM: Yes, many attended the workshop for many years; they literally grew up in it! And I kept in touch with them. Many have become excellent artists and some, art teachers. They still write to me, which is the most important thing. If somehow over the years, my name was forgotten by the Moussem’s organizers, young people who attended my workshops did not forget me …

MM: I’m curious to hear your thoughts on the independence of the Asilah Cultural Moussem compared to other more formal postcolonial festivals, which seemed more state-organized. For instance, the First World Festival of Black Arts in Dakar in 1966 was state-organized and highly political, as was the Baghdad biennale of 1974. Similarly, the Pan-African Cultural Festival in Algiers in 1969 had a distinctly centralized organization, despite its international character. Given that the Asilah Moussem was organized on a citywide scale rather than as a state-run event, was it more independent or less political from an official standpoint?

TM: We attended the Bagdad biennale of 1974 with Melehi—as the artists related to the Casablanca Art School representing Morocco. We attended the Pan-African Cultural Festival in Algiers in 1969 as well. All these events were fantastic artistically, but they indeed felt overtly political and official. Consequently, there were independent artist groups engaged in protest, like the Aouchem artist collective in Algeria and others. Asilah was different because it was organized locally by the municipality and the Al Muhit Cultural Association, and it involved local people primarily—this is why it was important to call it a moussem and not a festival.

MM: It’s quite interesting that it was just as international as in Algiers. It matched the internationalism of those earlier festivals, but the organization operated on a different scale. And, as you mentioned, it felt more local and grounded in some way, perhaps. So I believe it’s a very intriguing point regarding the originality of the Asilah Moussem within the broader context of postcolonial platforms, festivals, and transnational solidarities.

This conversation took place at a meeting of the Contemporary and Modern Art Perspectives (C-MAP) Africa group at MoMA in September 2024. The 2024 C-MAP Africa research program was conceived and organized by Beya Othmani (C-MAP Africa Fellow) and Ugochukwu-Smooth Nzewi (Steven and Lisa Tananbaum Curator, Department of Painting and Sculpture, and leader of the C-MAP Africa Group). Read more about C-MAP here

- 1Toni Maraini and Mohamed Melehi joined the teaching staff of the Casablanca Art School in 1964 and remained there until 1969. Maraini taught courses on modern art history and authored manifestos and theoretical essays related to the activities of the artistic group, collaborating with artists such as Farid Belkahia, Mohammed Chabâa, and Mohamed Melehi. Melehi offered painting courses with an experimental approach that included collage techniques. In addition to these initiatives, he established the school’s photographic studio and workshop. Both Maraini and Melehi played significant roles in the contemporary rediscovery and reevaluation of popular African arts and local Amazigh arts and crafts.

- 2The Présence plastique (Plastic Presence) outdoor public exhibition series was led by the core group of the Casablanca Art School (Farid Belkahia, Mohammed Chabâa, Toni Maraini, and Mohamed Melehi) joined by three other artists (Mustapha Hafid, Mohamed Hamidi, and Mohamed Ataallah) who organized a public display of their paintings on the Jemaa el-Fna Square in Marrakech (May 1969) and the 16 November Square in Casablanca (June 1969) as well as in different high schools in Casablanca in 1971, with the aim of creating a public platform and pedagogy around modern and contemporary art within Moroccan society.