Malika Agueznay was among the first woman modernist abstract artists in Morocco. She was a student at the Casablanca École des Beaux-Arts from 1966 to 1970, during the experimental tenure of the faculty known as the Casablanca School. Shaped by the formative experience within the school, she has also distinguished herself by the ways her research emphasizes her female identity. Throughout her career, she has elaborated on seaweed as a central motif in her abstract practice. This motif is both deliberately evocative of femininity and rooted in her own female perspective.

Malika Agueznay, among the first woman modernist abstract artists in Morocco, was able to forge a space for herself within a predominately masculine environment by insisting on the presence of a gendered expression of modernity through her research into seaweed. She was a student at the École des Beaux-Arts of Casablanca from 1966 to 1970, during the tenure of the faculty associated with the experimental Casablanca School. While she was supported by her professors, as one of few women within the student body, Agueznay was able to create a new perspective arising from the embodiment of her own femininity.1All information about Malika Agueznay’s career and her memories come from interviews with the author. Malika Agueznay, in discussion with Holiday Powers, Casablanca, September 21–22, 2022. Her work and viewpoints were shaped by the formative experience within the school, although she also distinguished herself in the ways in which her research emphasized her female identity. Agueznay was the only major female modernist artist linked to the École des Beaux-Arts at the time it was central to the debates around modernism in Morocco. Starting during her studies and expanding throughout her career, Agueznay elaborated on seaweed as a primary motif in her abstract practice. Drawing upon the influences of the Casablanca School, she engaged in abstraction that was deliberately evocative of femininity and of her own female perspective.

The École des Beaux-Arts was the locus of the Casablanca School, and Agueznay’s time as a student there coincided precisely with the movement’s brief heyday.2My book on the Casablanca School, Moroccan Modernism, is forthcoming from Ohio University Press. There is a growing body of literature about modernism and modernity in Morocco, with significant scholarly work by academics and curators including Cynthia Becker, Michel Gauthier, Brahim El Guabli, Olivia C. Harrison, Susan Gilson Miller, and Katarzyna Pieprzak. Information about the Casablanca School, in particular, has also been elaborated through significant exhibitions, including Moroccan Trilogy, 1950–2020 (Reina Sofia, 2021) and Casablanca Art School (Tate St. Ives, 2023), along with solo shows of Casablanca artists including Farid Belkahia and Mohammed Melehi at Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Mohammed Melehi at the Mosaic Rooms, and Mohammed Chebaa at the Cultural Foundation in Abu Dhabi. The Fondation Farid Belkahia also published a book of essays and archival materials (Farid Belkahia et L’École des beaux-arts de Casablanca, 1962–1974 [Paris: Skira, 2020]). Directed by modernist artist Farid Belkahia (1934–2014) from 1964 to 1972, the institution became a critical space for modernist experimentation and practice. It had been founded in 1950 under the French protectorate, and its faculty in the 1960s and early 1970s, which included Mohamed Melehi (1936–2020) and Mohammed Chebaa (1935–2013), actively rejected the remnants of colonialism, including Eurocentric teaching methods. Instead, as part of their broader anti-colonial politics, the school’s professors rooted their pedagogy in local visual culture, using objects such as rugs and metalwork as models in the classroom and leading students on field trips around Morocco to document and study applied abstraction within mosques and other local spaces. The École des Beaux-Arts remains open in Casablanca and has trained many women artists since Agueznay. Though there were women on the faculty when the institution was integral to the development of Moroccan modernism, including influential art historian Toni Maraini (born 1941), many of the female students did not go on to have significant careers in the arts. Agueznay is the only major woman artist linked to the institution during this pivotal time.

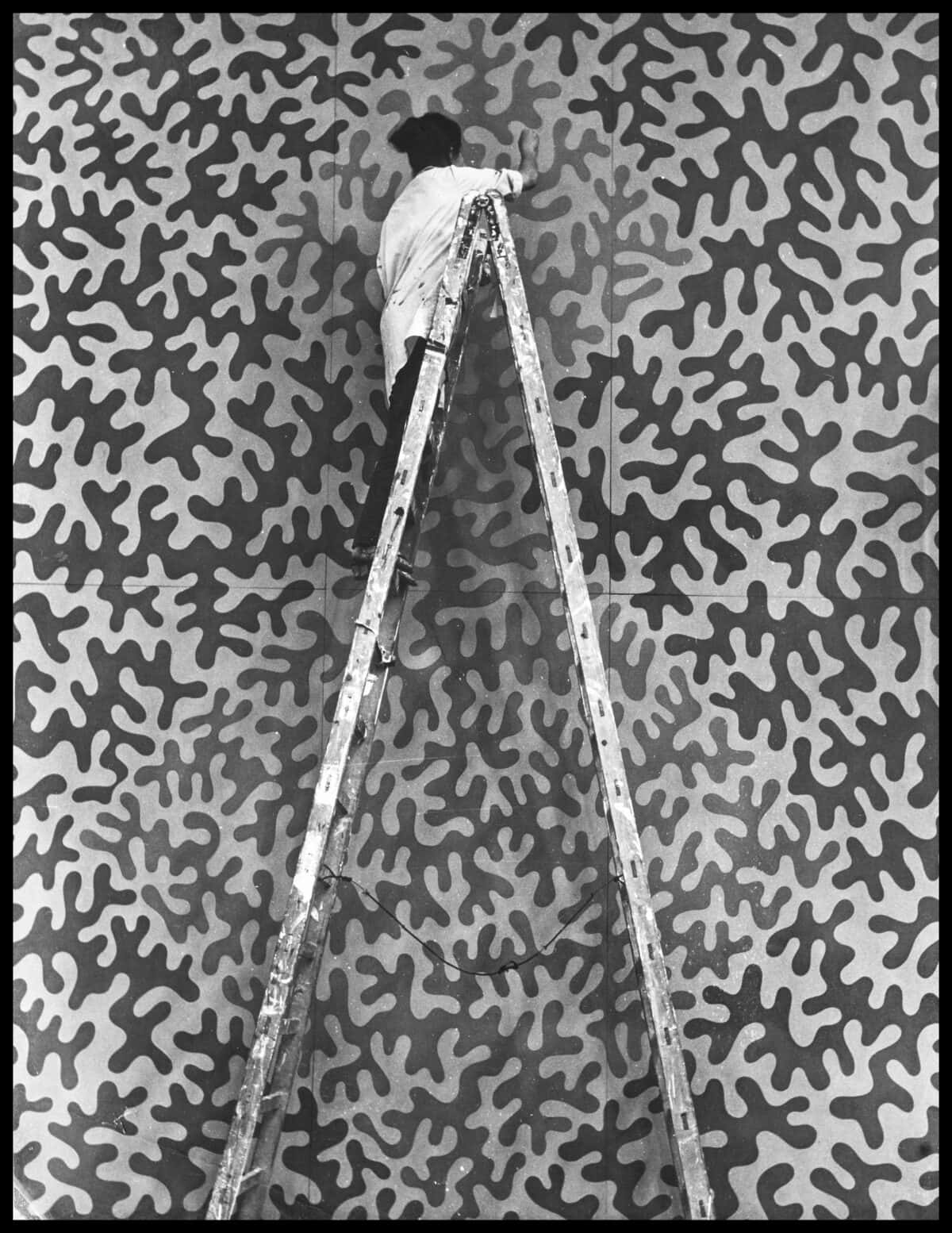

One of the key moments in the history of the Casablanca School is the 1969 manifesto exhibition Présence plastique, which was held in Jemaa el-Fna in Marrakech. In protest to an official salon organized by the city’s ministry of culture, six male faculty members displayed their work in this public square over ten days to engage a broader audience in the debates around modernism.3The Casablanca School artists organized this exhibition as a protest to the official salon in Marrakech, which they felt was unprofessional and not seriously invested in advancing modernist practices in the country. More broadly, the salon was in a government space that could be accessed only by presenting identification. Their protest exhibition was instead meant to engage a larger public and show that art was not only for an elite. Agueznay and her classmates accompanied their professors to Marrakech, witnessing and participating in their conversations with the public. The Casablanca School artists followed up this exhibition later that same year with another public exhibition, this one in Casablanca in the Place du 16 Novembre. Similar to the presentation in Marrakech, their goal was to reach a broader audience by bringing art to a more public setting and to encourage conversation about it. Unlike in Marrakech, however, their students, including Agueznay, participated—though they did not stay with their work, because, as Agueznay remembers, they had to return class. Including the students in this undertaking was part of the broader system of collaboration that the faculty tried to promote. According to Agueznay, the relationship with her teachers “was very friendly. It wasn’t the teacher where you had to stand at attention, let him pass. Not at all—it was contestation. When we didn’t understand, they would help us understand. We discussed things. Once or twice a week, we would have round tables, where each artist would go with his students, and we would sit and talk. There were permanent discussions.” This sense of being part of an ongoing collaborative intellectual pursuit informed Agueznay’s interest in collective practice and abstraction. In 1978, alongside her former professors, she was a founding participant in the first edition of what would become the annual Cultural Moussem of Asilah. In 1981, with many of the same people, she was involved in a public art project within the Berrechid psychiatric hospital, where in collaboration with one of the patients, she produced a ten-meter-long mural. In 1985, she created a large-scale mural in Asilah as part of the festival. These collaborative forms of public engagement were influenced by the formative ideas of the Casablanca School.

Agueznay entered the École des Beaux-Arts at age twenty-four. She was slightly older than her fellow classmates and already a mother, which further set her apart. Although there were very few women students—only three in her memory within the painting studio when she began—she felt supported by the faculty and other students, and was not only treated kindly and respectfully but also no differently. When pressed, Agueznay described some backlash once she had left the school and begun to maintain, as a woman artist, a modernist abstract practice. (“En tout cas, j’ai reçu des coups de bâton pour ça!”4“In any case, I got hit by sticks [experienced backlash] for that!”) While still a student, she insisted on creating a place for herself as a mother and artist, bringing her young child, Amina, with her on days she did not have childcare. As the institution was relatively small, Amina was able to sit in the corner, where she would play with clay provided by one of the professors. Agueznay remembers Belkahia raising his eyebrows at Amina’s presence each Wednesday, but Agueznay insisted that she could either come with her child or not come at all. She had a second baby while still a student, and so then both children accompanied her on field trips; she, in fact, attended Présence plastique with her newborn. Similarly, her children always joined her in Asilah, as they would be on school vacation during that time. Agueznay describes the collective effort of the festival, with the participation of whole families. Children would have drawing lessons or take part in artist-led workshops. When pressed about the challenges of balancing her practice and her role as primary caregiver, she deflected: “It was the only solution. . . . It was like when the artists got to the school, the most essential thing was art and research. . . . We all [the whole family] participated in the creation of the festival.” Agueznay created a space for herself as a mother and artist at a time when the possibility of maintaining both identities was a crucial aspect of the second wave feminist investigation. In her “Manifesto for Maintenance Art” (1969), for example, Mierle Laderman Ukeles (born 1939), specifically argues against the patriarchal American art system that deemed she could not be both a mother and an artist, and embodied that in different “maintenance” works. Similarly, in 1973, the collective Mother Art created a playground for the Feminist Studio Workshop in Los Angeles, making their children’s inclusion in art spaces part of their work. The presence of Agueznay’s children was not performative, but rather the result of necessity. She created this space for herself, though, at a time when there were no other female modernist artists in Morocco and when, in other parts of the world, artists were actively confronting what seemed to be a double bind.

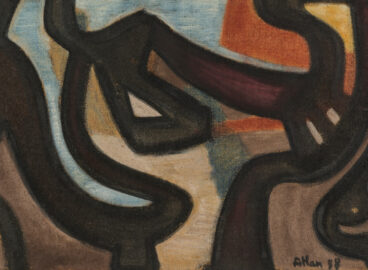

Agueznay’s practice can be seen structurally through the lens of feminist analysis, including in the groundbreaking way that she navigated her career as an artist and her role as a mother. Within the work itself, which consistently features the motif of seaweed, she also elaborated what she considered to be a specifically female form of abstraction. Recalling, perhaps, the marine plants and algae she would find as a child in summers on the coast, the motif in practice is not figurative. Far from being determined by mathematical systems, these organic shapes are formed instead by instinct, then further built up by the inclusion of texture, whether through cut wood, thickly applied ink, or sand within the paint. The abstraction thereby becomes rooted in the body, guided by feelings and the senses. Agueznay has linked the seaweed to the female form, and saw the rounded shapes, when she first developed them, as only possible from a female artist. Unlike the hard edges of the geometrical abstractions produced by other students, these rounded twisting shapes were, for her, rooted in her own female identity. Within an overwhelmingly masculine context, both at the École des Beaux-Arts and within the broader art scene in Morocco, Agueznay’s deliberate evocation of female identity and female form can be read as a concrete claim for female presence in what was a male-dominated field.

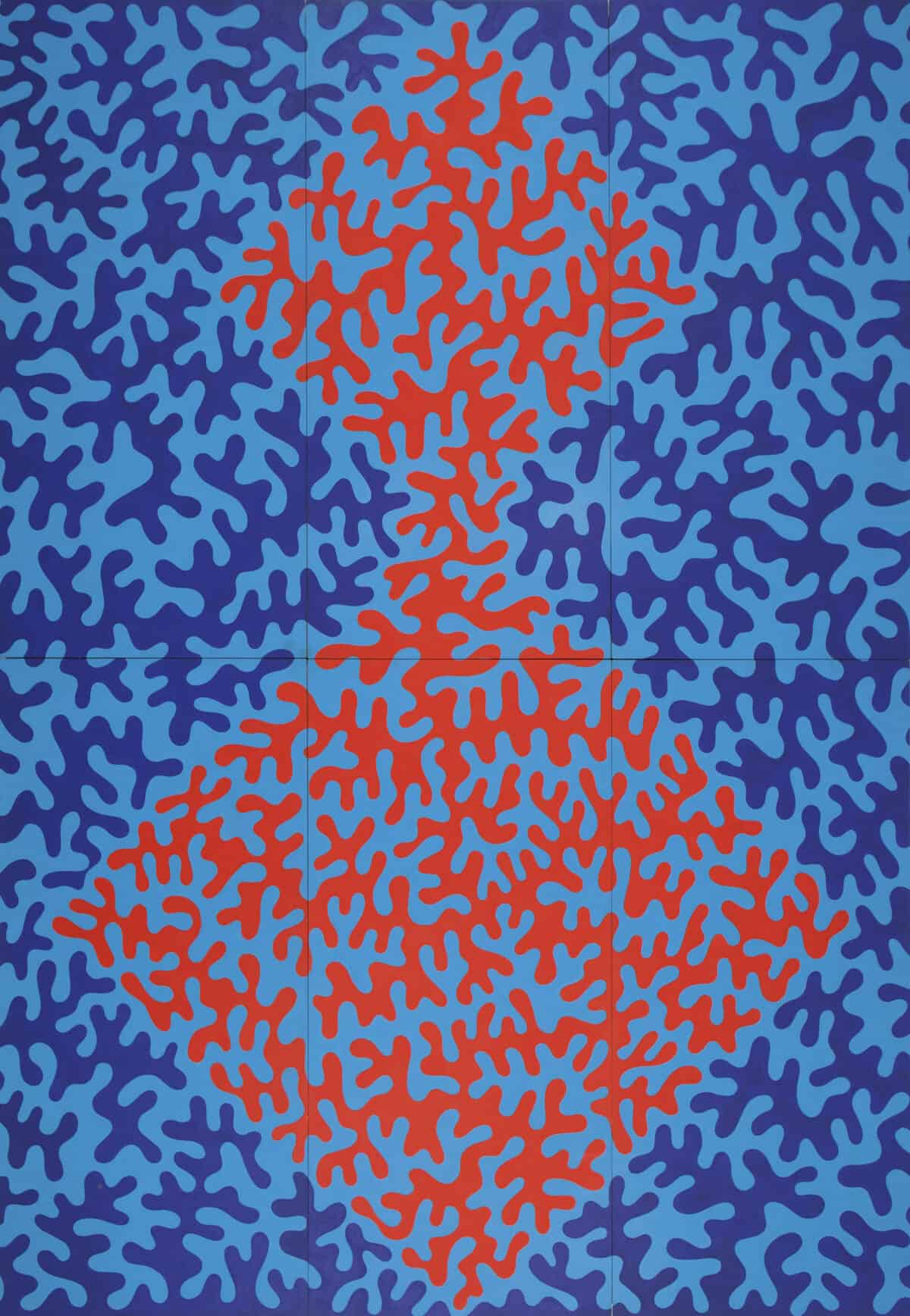

Over time, Agueznay has incorporated the seaweed form in different ways, in effect, pulling it in different directions: as pure abstraction, as the foundation for calligraphic text, as part of a distinct plant formation, or as a specific evocation of the female body. She has also used it across mediums, placing it at the center of her multifaceted practice, which has extended from printmaking and painting to sculpture and woodwork. She first used the motif in the monumental group of painted wooden panels she showed at the 1968 student exhibition. The six panels together measure 305 by 440 centimeters (approximately 10 by 14 1/2 feet), much larger than human scale. In the center of the grouping, there are two diamonds stacked vertically, the smaller one on top of the larger one. They connect organically, with the same seaweed contracting at the meeting point and continuing to expand into the lower shape. The background is sky blue, with the central diamonds in bright orange and the remaining seaweed a deeper marine blue. The whole work is covered in seaweed, and the central shape is thereby distinguished through the use of color; while there are distinct diamonds, there are no hard edges delineating them. The diamonds evoke the curves of a woman’s body. In its use of a singular sign that dominates the panels, the project seems equally influenced by imagery culled from rugs or jewelry. Indeed, the faculty insisted that students undertake rigorous research into forms rooted in local visual culture. The seaweed began from a formal interest. Struggling to find a theme for her final project, Agueznay was encouraged by Melehi to “do your lines,” and it was through visual experimentation that she settled on seaweed. Melehi himself, over the course of a career lasting almost sixty years, maintained a central interest in the motif of the wave, which he then used in various configurations and toward different ends. In the repetition over the span of her career of a central abstract motif, and in some ways the shared oceanic theme, Agueznay is clearly linked to Melehi, who encouraged her to stay with this project. However, there are obvious distinctions within their artistic endeavors. Melehi’s hard-edge waves are often in dialogue with science and cybernetics, and his abstractions seem to function as precise systems separate from human intervention. In contrast to Melehi’s coolly analytic abstraction, the organic shape of Agueznay’s seaweed seems lawless, growing upon itself in a generative abstraction. Built up with materials that add dimension, either through mixed-media application or the inclusion of sand in the paint, Agueznay’s work is also tactile. Her individual touch is always present. Agueznay pulled motifs, forms, and topics from the Casablanca School, while at the same time, carving out her own formal path and insisting on a female presence within a broader, predominantly masculine landscape.

Many of these ideas have coalesced in the importance of printmaking in Agueznay’s practice. She began printmaking in the first edition of Asilah Moussem in the workshop of Roman Artymowski (1919–1993), and went on to study in New York in the workshops of Mohammad Omar Khalil (born 1936) and Robert Blackburn (1920–2003).5Sumesh Sharma gives an overview of the printing workshop as part of the Cultural Moussem of Asilah. “I Carry Color,” Guggenheim Blogs, Guggenheim UBS Map, Middle East/North Africa, Perspectives, July 19, 2017, https://www.guggenheim.org/blogs/map/i-carry-color. She continued to explore printmaking in Asilah with Khalil, Blackburn, and Krishna Reddy (1925–2018), exhibiting her prints in group exhibitions there starting in 1979. She began leading this same workshop when Khalil left. Agueznay was the first woman printmaker in Morocco. Like in the rest of her practice, her prints primarily emphasize the seaweed motif and are built up to have different layers of texture. The physicality of the printmaking process has also been important to her, as she has strived to maintain her own touch and presence within this medium. Collaboration has likewise been central to this part of her practice, both in terms of her own education in different workshops and in the annual workshops she led in Asilah for over twenty years. More broadly, in becoming Morocco’s first woman printmaker and then incorporating printmaking as one part of her multidisciplinary practice, Agueznay has created a space for herself as an artist outside the boundaries of media and gender.

- 1All information about Malika Agueznay’s career and her memories come from interviews with the author. Malika Agueznay, in discussion with Holiday Powers, Casablanca, September 21–22, 2022.

- 2My book on the Casablanca School, Moroccan Modernism, is forthcoming from Ohio University Press. There is a growing body of literature about modernism and modernity in Morocco, with significant scholarly work by academics and curators including Cynthia Becker, Michel Gauthier, Brahim El Guabli, Olivia C. Harrison, Susan Gilson Miller, and Katarzyna Pieprzak. Information about the Casablanca School, in particular, has also been elaborated through significant exhibitions, including Moroccan Trilogy, 1950–2020 (Reina Sofia, 2021) and Casablanca Art School (Tate St. Ives, 2023), along with solo shows of Casablanca artists including Farid Belkahia and Mohammed Melehi at Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Mohammed Melehi at the Mosaic Rooms, and Mohammed Chebaa at the Cultural Foundation in Abu Dhabi. The Fondation Farid Belkahia also published a book of essays and archival materials (Farid Belkahia et L’École des beaux-arts de Casablanca, 1962–1974 [Paris: Skira, 2020]).

- 3The Casablanca School artists organized this exhibition as a protest to the official salon in Marrakech, which they felt was unprofessional and not seriously invested in advancing modernist practices in the country. More broadly, the salon was in a government space that could be accessed only by presenting identification. Their protest exhibition was instead meant to engage a larger public and show that art was not only for an elite.

- 4“In any case, I got hit by sticks [experienced backlash] for that!”

- 5Sumesh Sharma gives an overview of the printing workshop as part of the Cultural Moussem of Asilah. “I Carry Color,” Guggenheim Blogs, Guggenheim UBS Map, Middle East/North Africa, Perspectives, July 19, 2017, https://www.guggenheim.org/blogs/map/i-carry-color.