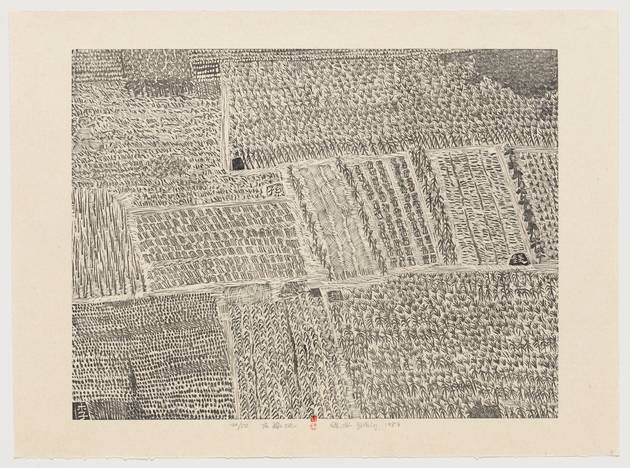

In Xu Bing’s Cropland, part of the Series of Five Repetitions (1987-88), Chinese characters double as landscape depiction, creating a liminal work that resonates between word and image, representation and abstraction.

To encounter the woodcut print Cropland (1987) by Xu Bing (b. 1955) is to visit a patchwork of garden plots, with vigorous lines denoting orderly rows of plants that recede gently into the distance. Looking closer, plant groupings come into focus, with different carving techniques distinguishing stalks, flowers, and fallow areas. Looking closer still, Chinese characters or hanzi are legible in corners of the plots. Reconsidering the composition as a whole, plantings and characters blend back into a landscape of marks.

These blendings—of plant and garden, individual plot and collective farm, word and image, representation and abstraction—help to locate Cropland in the time and place of its cultivation, specifically as a key moment in Xu’s artistic development in the Beijing region during and just after the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976).

Cropland is a single print from a Series of Five Repetitions (1987-1988), a seminal work exploring the printing process through landscape imagery. Conceived as part of his thesis project at the Central Acadamy of Fine Arts in Beijing, the artist printed the images in stages as he developed and then obliterated each one, beginning with a fully inked uncarved block, culminating in a legible landscape, and then ending with an overcarved, nearly blank sheet. The imagined landscapes draw upon Xu’s memories of working on a communal farm in the 1970s and also from quick schematic sketches of rural landscapes made during travel.

Landscape imagery, visualization of process, and word-image integration in Cropland anticipates their centrality to Xu’s subsequent work. This is seen most clearly in Book from the Sky (1987-1991), his landmark project documenting 4,000 invented characters, and “landscripts” (1999–2013), an investigation of different types of landscape painting in relation to Chinese writing systems.

A deeper dig into the work reveals how these themes represent the cultivation of an adaptive strategy by the artist. This becomes clearer by putting the work in biographical context.

Born in 1955 to educated parents who held positions at Beijing University, the family’s life was thoroughly disrupted by the Cultural Revolution. This experience profoundly influenced the artist, especially his “reeducation” at Shouliang Gou, a farming village 50 miles north of Beijing, from 1974 to 1977.1Xu Bing: a Retrospective (Taipei: Taipei Fine Arts Museum, 2014), 38.

By all accounts Xu adapted by embracing his “advanced educated youth post,” detailed in his brief memoir “Ignorance as a Kind of Nourishment.”2Xu Bing. “Ignorance as a Kind of Nourishment,” translation by Jesse Robert Coffino and Vivian Xu, in Qishi Niandai (Hong Kong: SDX, 2009).http://www.xubing.com/en/database/essay/409 There, he realized, “where no one cared about his background,” one could work hard and “prove himself a useful person.”3Ibid. And this he did, tending fields and minding livestock while mobilizing his writing, drawing, and design skills in service of the village. Relevant to Cropland, the artist recalls, “The task I feared most, squatting down to pick weeds, meant that you had to spend the day moving around in a squat . . . . The days are tough in a rural village, but we didn’t feel it then. It’s what we had rushed there for.”4Ibid.

As a result, by the late 1970s Xu was recruited in the first generation of students to attend one of the newly-reinstated art academies. As the rare “educated” member of a class chosen for their Maoist credentials, the artist recalls being “earnest and dutiful for a reason . . . . Some of us had landlords in our families and others were labeled bourgeois or deemed spies with overseas connections.”5Ibid.

At the Academy, blending with fellow students also meant harmonizing disjunctive pedagogies, where residual Beaux-Arts methods (copying from Classical plaster casts, for example) was integrated with the Maoist ethos of “art for the people.” Printing in particular, the department to which he was assigned, carried strong positive associations with the populist New Woodcut Movement (1912–1949) and his instructors were well respected for their practice in that mode.6Xu Bing: a Retrospective, 34.

At the same time, emerging art and social movements meant new ideas and new possibilities for an emerging printmaker in Beijing. The surfacing of No Name painters, working underground since the late 1950s, opened up a space for subjective experience in art, presaging the inception of the Stars Group and April Photography Group in the late 1970s, groups that overtly pushed boundaries on aesthetic free expression and personal points of view.7For more on this period, see Minglu, Gao. Total Modernity and the Avant-garde in Twentieth-century Chinese art (Cambridge: MIT, 2011). In this context of change within and beyond the art scene, Xu closely followed these developments and made sense of them as an observer: “[W]hile others filled Tiananmen Square with poems and speeches,” he reflects, “I was sketching among the crowd. I believed it was what an artist should do.”8Xu Bing. “Ignorance as a Kind of Nourishment.” For another artist’s sketched observations of mass action, see Diego Rivera’s May Day, Moscow (1928).

In that setting, an exploration of the printing process through remembered images of collective farming made both aesthetic, political, and personal sense as a thesis project. At the time of the work’s completion in the late 1980s, the audience for Five Repetitions was largely local, but it became well known in that context, received as a successful integration of the Modern Woodcut tradition with subjective expression to convey a sense of the quotidian.9Xu Bing: a Retrospective, 145.

This integration of Socialist Realism, process-oriented printing, and individual experience into the Five Repetitions goes deeper however. Further meanings surface by digging further into the artist’s blending of word and image, land and landscape, individual and collective into Cropland.

Of the ten works in the series, only Cropland features actual hanzi. The four characters read Zhao, Qian, Li, and Sun. They refer to the first names in a Song dynasty (960–1279) list of one hundred prominent families. Many Chinese viewers would recognize the list as the source for the phrase “old one hundred names,” a way to describe mass, shared culture. In addition, reference to the Song dynasty is significant as the origin point for traditional Chinese landscape painting and a unified writing system (typography in Book from the Sky is modeled on Song-era letterforms).10Vainker, S. J. Landscape Landscript: Nature as Language in the Art of Xu Bing (Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 2013), 111.

The significance of planting family names into communal cropland is further revealed by an alternate translation of the work’s Chinese title (庄稼地, zi liu di): Family Plots or Private Plots. The term is specific, defining areas allotted to individuals within collective farms,11Li Gucheng. A Glossary of Political Terms of the People’s Republic of China (Beijing: Chinese University Press, 1995), 597. rare instances of self-determination in a nationalized system. Though considered the “tail end of capitalism,” as Mao put it, the practice more or less continued until dissolution of the commune system after Mao’s death.12Li, Huaiyin. Village China Under Socialism and Reform: A Micro-History, 1948-2008 (Stanford: Stanford University, 2009). The term also conveys intimacy with and fondness for rural life which Xu could certainly claim.

This distinction between individuated family plots and anonymized cropland becomes clear by comparison with another work in the series, titled Field (田.1987) While the mark-making is similar, a directly aerial view suggests a psychological distance remote from the situated perspective of Cropland/Family Plot, where one can imagine standing in the narrow walkways between plantings. Similarly, a mass of tadpoles swarms a flooded area of the Field, perhaps suggesting collectivism.

In both farming and language, meaningful units are cultivated in an orderly and repetitive way to yield sustenance and nourish new growth. Bringing the Repetitions to fruition by working and re-working the images section by section evokes both the repetitive tilling of land and the process of becoming literate by copying thousands of characters stroke by stroke.

In this way the plantings also evoke the modularity of written Chinese, in which characters can be arranged on a grid to yield multiple readings, as seen in the artist’s Magic Carpet (2006). Writing about Repetitions at the time, Xu also describes the visual regularity as a response in part to contemporary life, where “dramatic advances of industrialization and concomitant standardization” could be infused with “a deeply spiritual, incredibly rational, man-made beauty. . . .”

13Xu Bing. “A New Exploration and Reconsideration of Pictorial Multiplicity” in Meishu 278 (1987), 50-51. http://www.xubing.com/en/database/writing/365

Was the composition of Cropland determined by a formal system? Evidence of Xu’s process suggests an intentional but not formulaic approach. To develop the image, he worked the woodblock surface intuitively and spatially, carving out almost all the plots from visual foreground to background. This suggests a process more consistent with the phrase “meaning comes before the brush strokes,” familiar to some Chinese artists, than to a strictly rule-based system. Still, Cropland “reads” like a newspaper page, complete with individual stories and varied typefaces.

These subtexts emerge by close observation and close reading. By articulating some of the stories embedded in Cropland, a rich landscape is revealed, one that incorporates Xu Bing’s life experience and presages major themes of his subsequent work. As the artist wrote at the time,

it breaks with the common understanding that works of art always appear in rigid form, revealing an aspect of art that is hidden . . . . it not only emphasizes process, but also gives complete expression to the artist’s line of thinking.14Xu Bing. “A New Exploration and Reconsideration of Pictorial Multiplicity.”

Xu Bing’s Cropland is on view in gallery 207 of MoMA’s reinstalled galleries.

- 1Xu Bing: a Retrospective (Taipei: Taipei Fine Arts Museum, 2014), 38.

- 2Xu Bing. “Ignorance as a Kind of Nourishment,” translation by Jesse Robert Coffino and Vivian Xu, in Qishi Niandai (Hong Kong: SDX, 2009).http://www.xubing.com/en/database/essay/409

- 3Ibid.

- 4Ibid.

- 5Ibid.

- 6Xu Bing: a Retrospective, 34.

- 7For more on this period, see Minglu, Gao. Total Modernity and the Avant-garde in Twentieth-century Chinese art (Cambridge: MIT, 2011).

- 8Xu Bing. “Ignorance as a Kind of Nourishment.” For another artist’s sketched observations of mass action, see Diego Rivera’s May Day, Moscow (1928).

- 9Xu Bing: a Retrospective, 145.

- 10Vainker, S. J. Landscape Landscript: Nature as Language in the Art of Xu Bing (Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 2013), 111.

- 11Li Gucheng. A Glossary of Political Terms of the People’s Republic of China (Beijing: Chinese University Press, 1995), 597.

- 12Li, Huaiyin. Village China Under Socialism and Reform: A Micro-History, 1948-2008 (Stanford: Stanford University, 2009).

- 13Xu Bing. “A New Exploration and Reconsideration of Pictorial Multiplicity” in Meishu 278 (1987), 50-51. http://www.xubing.com/en/database/writing/365

- 14Xu Bing. “A New Exploration and Reconsideration of Pictorial Multiplicity.”