Following the opening event in which Xiao Lu’s shot at her own installation, Dialogue (1989), which caused the exhibition at the National Art Gallery in Beijing to close, the work has paradoxically become both iconic and obscured. Initially conceived to address gendered violence, the piece was later absorbed into the history of violence of Tiananmen Square that followed months later—a fact that the artist has creatively appropriated in her own evolving relationship to it.

“Truth never yields itself in anything said or shown. One cannot just point a camera at it to catch it: the very effort to do so will kill it.” —Trinh T. Minh-ha1Nancy N. Chen, “‘Speaking Nearby:’ A Conversation with Trinh T. Minh-ha,” Visual Anthropology Review 8, no. 1 (March 1992): 87, https://doi.org/10.1525/var.1992.8.1.82.

Xiao Lu’s Dialogue (1989) has been shrouded in layered histories and conflicting narratives since it was brought to fruition at the opening of the China/Avant-Garde exhibition in the Chinese National Art Gallery, Beijing. In February 1989, Xiao Lu shot two bullets into the mirror panel of her installation, causing its immediate shutdown. Born out of Xiao Lu’s struggle to talk openly about the sexual traumas that afflicted her, Dialogue transformed into a platform for broader conversations about Chinese avant-garde art and the political and social ramifications of the art movement. The appropriation of Dialogue into these discourse frameworks shaped the historical trajectory of the work to the extent that the writing and revision of history became a large part of Dialogue.

Known as “The Gunshot Incident,” Xiao Lu’s shooting of her installation became the pinnacle of Dialogue. It triggered local and international conversations that extended beyond the artist’s initial concerns when developing the work. In the American media, Xiao Lu’s shots were described as a shocking, political act that tested the limits of China in transition in the 1980s.2See, for example, Edward M. Gomez and Jaime A. Fior Cruz, “Condoms, Eggs And Gunshots,” Time, March 6, 1989, and Daniel Southerland, “China’s Dada Shock,” The Washington Post, February 13, 2019. Seven days after “The Gunshot Incident,” Xiao Lu’s lover, Tang Song, submitted a public declaration to one of the curators, Gao Minglu, explaining that the work was an artistic endeavor that sought to deepen understandings of art and its social values.3Gao Minglu, “Foreword,” in Dialogue, Xiao Lu (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2010), ix. Furthermore, because the declaration was co-signed by Tang Song, he became credited as the second author of Dialogue. The contextualization of the work within the tense sociopolitical climate of China was further entrenched when, four months after Xiao Lu’s performance, the Tiananmen Square protests broke out and her performance was retroactively labeled “the first shots of Tiananmen.”4Gao, “Foreword,” viii. Dialogue became defined by its abstract relationship to sociopolitical currents rather than the immediate connection between the performance and the installation. In his essay “Can We Talk about Dialogue? A Pre-script to Art and China after 1989,” David Borgonjon critiqued Gao Minglu’s comment that, after the gunshots, the interpretation of Dialogue belonged to society. Instead, argued Borgonjon, “the collective declaration of the death of the author here [looked] like an excuse for appropriation.”5David Borgonjon, “Can We Talk about Dialogue? A Pre-script to Art and China after 1989,” MCLC Resource Center, December 14, 2017, http://u.osu.edu/mclc/2017/12/14/can-we-talk-about-dialogue/

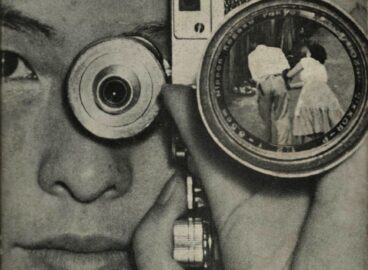

The complexities surrounding the appropriation of Dialogue are echoed through the blurred lines of authorship and ownership that surround the photographic representation of the work. Since 2004, Xiao Lu has been increasingly vocal about Dialogue through conversations with curators and by participating in interviews.6She wrote letters to Gao explaining her perspective on Dialogue, for example, and she conducted interviews for art institutions such as the Tate and MoMA. Outside these formal channels of communication, Xiao Lu has also undermined the hegemonic historicizations of Dialogue through creative interventions. In 2006, Xiao Lu enlarged and printed 10 editions of an iconic photographic representation of Dialogue. Shot in 1989, the image shows Xiao Lu’s back to the audience. Although the exhibition was packed with people, only the artist and her installation are captured within the photograph’s frame. Signed and dated “1989,” Xiao Lu’s appropriation of this archival photograph inverts the absorption of Dialogue in broader sociopolitical and historical frameworks. The photograph, part of the Archive of Chinese Avant-Garde Art, was provided to Xiao Lu by Wen Pulin, her classmate who documented and received multiple photographic records of Dialogue following “The Gunshot Incident.”7In an audio interview with MoMA, the artist explained the details regarding the exact provenance of this image. Through the appropriation of this image, the collective memory of Dialogue is reclaimed by the artist as part of her reflexive interventions into the historical constructions of Dialogue.

Rather than presenting the photograph as an archival document that masks the interventions of the author, Xiao Lu exposes the material limitations of the photographic archival media. In the editioned photograph of Dialogue, only Xiao Lu is in focus. The composition leads the viewer’s eye from Xiao Lu’s outstretched arm towards the sculptural installation in the background, the target of Xiao Lu’s aggression. However, the grain of the photograph hinders, without completely obscuring, the details of the sculpture. Comprised of two fabricated, symmetrical telephone booths connected by a mirrored panel, Dialogue depicts a phone conversation between a man and woman. In the left booth, Xiao Lu inserted a life-size photograph of a figure in a skirt on the phone, and, in the opposing booth, a figure dressed in pants. The booths flank a red telephone that sits on a pedestal in the center of the installation, in front of the mirrored panel. The handset dangles loosely from its cord, suggesting a broken line of communication. Seen in relation to the installation, it is difficult to separate Xiao Lu’s gunshots from the reference to communication in heterosexual relationships. The obfuscation of the installation in the photograph calls to mind the blatant omissions of the sculptural references in early interpretations of the work. Through these material distortions, the photographic representation of Dialogue challenges viewers to reflect upon the ways in which historical narratives are constructed.

In his foreword to Xiao Lu’s fictional autobiography Dialogue, Gao Minglu wrote that “Xiao Lu targeted our reality.”8Gao, “Foreword,” xiv. Rather than playing into the dialectical positions that restrict the ownership of her work (hers vs. the masses) and the interpretations of Dialogue (personal vs. sociopolitical), Xiao Lu reveals the complex human and media networks that have shaped interpretations of Dialogue—how they enriched the work with sociopolitical meaning that she never intended, but how they also delegitimized her gendered experience as a social and political issue. Through the photographic representation of Dialogue, Xiao Lu invites the audience to partake as a witness: to question the ways in which historical reality is constructed and truth obscured.

- 1Nancy N. Chen, “‘Speaking Nearby:’ A Conversation with Trinh T. Minh-ha,” Visual Anthropology Review 8, no. 1 (March 1992): 87, https://doi.org/10.1525/var.1992.8.1.82.

- 2See, for example, Edward M. Gomez and Jaime A. Fior Cruz, “Condoms, Eggs And Gunshots,” Time, March 6, 1989, and Daniel Southerland, “China’s Dada Shock,” The Washington Post, February 13, 2019.

- 3Gao Minglu, “Foreword,” in Dialogue, Xiao Lu (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2010), ix.

- 4Gao, “Foreword,” viii.

- 5David Borgonjon, “Can We Talk about Dialogue? A Pre-script to Art and China after 1989,” MCLC Resource Center, December 14, 2017, http://u.osu.edu/mclc/2017/12/14/can-we-talk-about-dialogue/

- 6She wrote letters to Gao explaining her perspective on Dialogue, for example, and she conducted interviews for art institutions such as the Tate and MoMA

- 7In an audio interview with MoMA, the artist explained the details regarding the exact provenance of this image.

- 8Gao, “Foreword,” xiv.