A close examination of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company (MCDC)’s 1964 stop in Tokyo allows for a better understanding of how mutually significant this encounter was for the Japanese avant-garde and Cunningham and his close collaborators Robert Rauschenberg and John Cage.

John now feels that the time is propitious for Merce to undertake not only a trip to Japan, but a more extensive tour, if possible, a round-the-world tour.

Letter from David Vaughan to Kozo Igawa, June 17, 1963. Keio University Art Center Archives

At the age of eighty-six, Merce Cunningham made a final trip to Tokyo to accept the 2005 Praemium Imperiale prize, an award he shared with pianist Martha Argerich, designer Issey Miyake, architect Yoshio Taniguchi, and artist Robert Ryman. Given by the Japan Art Association in honor of Prince Takamatsu, the prestigious prize recognizes those who have “contributed significantly to the development of international arts and culture.”1Letter from David Vaughan to Kozo Igawa, June 17, 1963. Keio University Art Center Archives. How far things had evolved since the Merce Cunningham Dance Company (MCDC) made their first turbulent visit to Japan as the final installment of their monumental 1964 world tour. After six months on the road, the company’s dynamics reached a breaking point in Tokyo, and the fundamental structure of the group was on the brink of major change: Robert Rauschenberg, who had spent a decade as the MCDC’s resident designer and stage manager, decided to end his collaborative relationship with the company2Rauschenberg resumed collaborating with Cunningham on the 1977 dance Travelogue, and subsequently designed the costumes and décor for the MCDC repertory dances Interscape (2000) and XOVER (2007), as well as Immerse (1994), a backdrop that was used for site-specific Events. and depart, as did three of Cunningham’s eight dancers.

But more than simply signifying a moment of unraveling, MCDC’s Japanese residency comprised a generative exchange that was made possible because of the unique receptivity with which the Japanese avant-garde arts community, particularly in Tokyo, received them. In many ways this group of artists, musicians, designers, dancers, writers, and patrons greeted the company’s presence with a mutually engaged and ambitious spirit. At a time when European and American publications repeatedly framed Cunningham’s work as a binary to ballet (ascribing it as “modern ballet,”3Charles Greville. “The new ice-breakers of modern ballet.” Daily Mail. July 28, 1964. “pop ballet,”4“Pop Ballet.” Time. August 14, 1964. and “anti-ballet”5A. V. Coton. “‘Anti-ballet’ presented with apologies.” Daily Telegraph. August 6, 1964.), the surrounding critical discourse in Japan focused on a different dimension of the work. Japanese artists and critics made more explicit connections between the work and its relationship to chance and indeterminacy, concepts that were central to the paradigm-shifting collaborations of Cunningham, the composer John Cage, and Rauschenberg. MCDC’s performances had the power to sharpen one’s attunement to the serendipity and indeterminacy of disparate simultaneous occurrences—even if these events comprised the quotidian “whistle of the tofu shop and [the sound from] the neighbor’s TV.”6Ichiyangi Toshi, in the Sogetsu Art Center program for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, 1964. Keio University Art Center Archives. As Tokyo’s residents adjusted to the extensive modernization of their city for the 1964 Olympic Games,7Hiroko Ikegami, The Great Migrator (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2010), p. 168. the exposure to Cunningham’s work could also instigate a new way of observing this changing landscape and the inadvertent choreography, scenography, and scores of daily urban life. A closer examination of the company’s 1964 stop in Tokyo allows for a better understanding of how mutually significant this encounter was for everyone involved.

Before their historic 1964 journey, MCDC had experienced only modest success in the United States, and acquired limited recognition abroad. But a dramatic shift occurred during the course of their six-month trip through Europe and Asia, and they rapidly acquired an international following and world renown. More than just embodying the defining moment when the dance company, as a single entity, rose to international acclaim, the tour also prompted new encounters that would profoundly shape the individual lives and practices of its participants. The members of the tour comprised a group of dancers, musicians, visual artists, and administrative personnel including Cunningham, Cage, Rauschenberg, David Tudor, Carolyn Brown, Shareen Blair (only through the London segment of the tour), William Davis, Viola Farber, Deborah Hay, Alex Hay, Barbara Lloyd [Dilley], Sandra Neels, Steve Paxton, Albert Reid, Lewis Lloyd, and David Vaughan. Spanning thirty cities in fourteen countries, the journey reflected a composite of extremes. As dancer Barbara Dilley recalls, “John and Merce and Bob were stars in many of those places, and we were met by [those] who recognized them as stars. . . . John of course had protégés everywhere. . . .”8Barbara Dilley, interview with the author, June 2012. Walker Art Center Archives. In London, one of the most decisive turning points of the trip, the company was offered an extended month-long run, upgrading to the West End’s Phoenix Theatre, where they performed to packed houses and received ecstatic press headlines such as “The Future Bursts In.”9Alexander Bland. “The Future Bursts In.” Observer Weekend Review. August 2, 1964. In spite of these successes, they were also subject to worrisome financial shortfalls, brutal physical fatigue, and the irreversible growing pains of an entity that would never again operate on a more modest Volkswagen bus scale.10In 1956 the company toured across the United States in a Volkswagen Microbus, with all of the personnel, costumes, and sets packed snugly into the vehicle. This period marked an earlier, more familial time in the company’s history. One month the company was the buzz of London’s West End, and the next, after a series of miscommunications concerning their performances in Chandigargh, India, a theater affiliate apologized, “If we’d known how good you were, we wouldn’t have treated you so badly.”11Carolyn Brown. Chance and Circumstance (New York: Knopf. Second edition, 2008), p. 433.

EARLY TOKYO CONNECTIONS

Although serendipity played a role in shaping facets of the tour, a closer examination also reinforces that this was an odyssey built upon relationships and influences extending back over multiple decades. In 1947 Cunningham and Cage had collaborated with the Japanese-American artist Isamu Noguchi on the one-act ballet The Seasons for Lincoln Kirstein and George Balanchine’s Ballet Society (which became the New York City Ballet the following year). Cunningham and Noguchi previously knew each other through their affiliations with the choreographer Martha Graham; Cunningham had performed as a soloist in her company from 1939 to 1945, and Noguchi frequently worked with her as a set designer. Noguchi was instrumental in putting Cage in touch with Akiyama Kuniharu, the avant-garde composer, music critic, and poet who in the early 1950s was a member of the newly founded collective Jikken Kobo (Experimental Workshop).12For more on Jikken Kobo, see https://post.moma.org/apn-portfolios-and-jikken-kobo/The young Akiyama wrote a series of letters to Cage in 1952 in which he expressed his hope that Cage and his music would gain increased presence in Japan:

All members of our “Jikken Kobo” have been combined in their opinion and wish that your brilliant works should be played and introduced to [the] public in Tokyo. . . . This ardent aspiration of ours has been made more and more intensified since I, Mr. K. Akiyama, a member of the group, had a fortunate chance lately to make an interview with Mr. Isamu Noguchi, who gave me detailed knowledge of your recent activities.

Letter from Akiyama Kuniharu to John Cage, April 18, 1952. John Cage Correspondence, Northwestern University Music Library.

It should be of the utmost value to the Japanese public and cause a big rejoice to us if you would kindly send us any of your works recorded on tape. . . . If we could see you here in the near future, it is “Banzai” to all of us!

Ibid., December 29, 1952.

Twelve years later Akiyama, who by that time was regularly organizing events at the Sogetsu Art Center, served as one of MCDC’s hosts during the company’s stay in Tokyo. In May 1955 one of the company’s earliest performances, at the Henry Street Playhouse on New York’s Lower East Side, was sponsored by the Japan Society, another connection that was likely arranged through Cage,13Brown, Chance and Circumstance, p. 118. whose serious interest in Buddhist philosophy led him to regularly attended D. T. Suzuki’s lectures on Zen Buddhism at Columbia University.14John Cage and Joan Retallack, Musicage (Hanover, NH: Wesleyan Univ. Press, 1996), p. 52. Both he and Cunningham would also subsequently visit Suzuki in Kamakura on respective future visits to Japan in 1962 and 1964. In 1959 the art critic Tono Yoshiaki traveled to New York, where he became friends with Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, returning to Japan to “promote the new generation of American artists”15Hiroko Ikegami, The Great Migrator (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2010), p. 162. and to write on Cage and Rauschenberg.16Ibid., pp. 162–163. With proponents such as Tono, the work of Rauschenberg and Cage and their collaborations with Cunningham would have had heightened visibility in Japan.

By the early 1960s Cage was working closely with the composer Ichiyanagi Toshi, his former student, who would play a vital role in arranging the Cunningham Company’s 1964 visit. Cage performed Ichiyanagi’s compositions at his own concert engagements in Europe and prior to 1964 had asked him to provide the music for several Cunningham dances, including Waka (1960) and Story (1963). In 1961 Ichiyanagi performed works by Cage and Tudor at the Osaka Contemporary Music Festival, where visual artists, architects, and members of the Gutai group were part of the audience.17Ichiyanagi Toshi, interview with the author, April 26, 2013. Walker Art Center Archives. This exposure further primed members of the Japanese avant-garde to receive Cage and Tudor with enthusiasm when the two musicians made their inaugural visit to Japan in 1962. The occasion was a residency sponsored by the Sogetsu Art Center, where the two musicians presented a series of concerts (including performances with Ichiyanagi and Yoko Ono) that paved the way for the Cunningham Company’s visit two years later.

PREPARATIONS AND FUNDING CHALLENGES

Some of the finest ambassadors of the American arts come to Europe without a State Department blessing, blowing their own small horns. Judging from the “bravos” that saluted the end of tonight’s program, the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, which is beginning a round-the-world tour with a short run here [in Paris], is worth its weight in taxpayer’s gold.

Jean-Pierre Lenoir, “US Dance Company Makes Paris Debut,” New York Times, International Edition, June 15, 1964.

By May 1963 arrangements for the company’s journey to Japan were already intensively underway. There is a prophetic tone of readiness in David Vaughan’s first letter to Sogetsu administrator Igawa Kozo in which he relayed Cage’s assessment that the time was right for Merce to undertake “not only a trip to Japan, but a more extensive tour.”18Letter from Vaughan to Igawa. Prior to MCDC’s 1964 visit, other ballet and modern dance companies from the US had been making tours to the region for nearly a decade. In an introductory message printed in the Sogetsu Art Center’s Cunningham residency program booklet, Edwin O. Reischauer, US Ambassador to Japan from 1961 to 1966, proudly outlined this history of exchange:

In none of the performing arts has there developed within the past decade a more active and rewarding association between Japanese and American creative talent than in the field of contemporary dance. . . . Since the visit of Martha Graham to Japan in 1955, Japanese audiences have seen performances by such other major American contributors to the development of contemporary dance styles as the New York City Ballet, the Alvin Ailey–Carmen De Lavallade Dance Company, and—most recently—the Jose Limon Dance Company. . . it is gratifying to note that the Japanese composer Toshi Ichiyanagi has played an important role in the creative work of this avant-garde group of artists, whose achievements have been hailed by critics, not only in the United States, but in Europe. . . .

Sogetsu Art Center program for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, 1964. Keio University Art Archives Archives.

Although Reischauer’s statement is resoundingly positive, he omitted the critical fact that all of the other companies he mentioned had received sponsorship from the United States Department of State, a form of support not extended to the Cunningham Company in 1964. Correspondence from Cage to Ichiyanagi suggests that the company had initially pursued State Department funding19Letter from John Cage to Ichiyanagi Toshi, April 22, 1963. Keio University Art Archives. but those efforts never yielded anything. While federal support remained elusive, the company did receive a generous grant from the JDR 3rd Fund to help underwrite their expenses in Asia.20David Vaughan, “Adventures on a World Tour,” New York Times, January 3, 1965.Yet even with such support, the tour consistently operated on a shoestring and accumulated a substantial deficit that would follow the company home to New York.

ARRIVAL

A lot of the imprint of that experience was about time. Time never was the same after that tour. One learned to live in a very different kind of time, hours and hours of setting up things and rehearsing in dark spaces.

Dilley, interview, June 2012. Walker Art Center Archives.

When the company finally arrived in Tokyo, an enthusiastic group of friends and supporters were there to meet them. According to dancer Carolyn Brown, “Toshi Ichiyanagi, Mayuzumi Toshiro, and many other Japanese composers were there to greet us—plus artists and theater people.”21Brown, Chance and Circumstance, 2008, p. 438. This warm welcome was a prelude to the camaraderie and hospitality that would surround the company throughout its stay in Japan, a distinct contrast to the muted fanfare the group had received six months earlier in Strasbourg, on the first stop of the tour. There, “after an eight-hour trip [from Orly airport], we arrived . . . and moved into a small, inexpensive hotel near the railroad station and overlooking prostitute row.”22Ibid., p. 376. Some members of the touring cohort immediately noticed resonances between Tokyo and an American metropolis. Cunningham wrote that his “first feeling of Tokyo was of a twentieth-century American city as we drove from the airport to the International House.”23Merce Cunningham, “Story of a Dance and a Tour. Part 3,” Dance Ink, 1994, p. 35. Brown found the city to be a “mix of 1950s Time Square, Fourteenth Street, and Canal Street, with a touch of Detroit and L.A.’s Sunset Boulevard thrown in, all bubbling in a contemporary Japanese stew.”24Brown, Chance and Circumstance, p. 438.Rauschenberg, however, had a different impression of the city’s pace: “Tokyo is not like New York, which is always in a hurry, but rather is a city with many powerful centers dispersed all over.”25Yoshiaki Tono, “Pop Art and Myself: An Interview with Rauschenberg,” Geijutsu Shincho, no. 182, February 1965, p. 58. Quoted in Ikegami, The Great Migrator, p. 169. It is worth noting that Rauschenberg’s use of the image—“powerful centers dispersed all over”—evokes one of Cunningham’s radical attitudes toward choreography, as well as Rauschenberg’s own approach to designing the dance company’s sets and costumes. Rather than privileging a single point of focus, many of Cunningham’s dances, like Rauschenberg’s backdrops and set constructions, are designed with many centers, so that they can be viewed from multiple angles, freed from the limitations of a single audience/stage orientation.

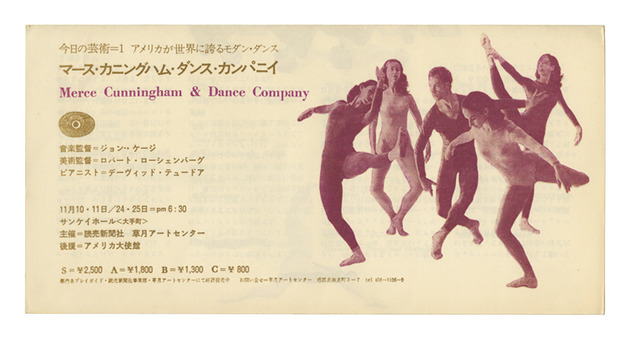

The day after their arrival in Tokyo, the company presented an open rehearsal at Sankei Hall “with a crowd of photographers clicking away at every moment. . . . ”26Brown, Chance and Circumstance, p. 438 Advance publicity generated by the Sogetsu Art Center made Tokyo one of the tour’s most elegantly advertised and thoroughly documented stops. Lushly colored posters and programs designed by Awazu Kiyoshi, extensive photography and press pieces by respected artists and critics such as Akiyama Kuniharu, Ichiyanagi Toshi, Kenzaburo Oe, and Yoshiaki Tono underscored the interest of the Japanese in engaging with the company on a more intensive level, aiming to create something new and unique out of the exchange, as opposed to simply hosting a formulaic series of performances.

The repertory on the world tour consisted of a sizable roster of seventeen dances performed by various configurations of the group of ten (later reduced to nine) dancers, including Cunningham, himself. Story, a full-company piece that was presented multiple times in Tokyo, received prominent mention in many of the Japanese press reviews, at least in part because the dance offered the most explicit illustration of how chance and indeterminacy could create a unique performance each time the work was performed. The dance was one of Cunningham’s most overt experiments in applying chance procedures both to the choreographic process and to the performances of the work. Individual dance phrases were set, but the order in which they were performed to Ichiyanagi’s score Sapporo was determined anew, by chance, each night. Rauschenberg and Alex Hay also produced a unique decor for each performance, sourcing local materials “in or outside the theater, when and where the dance is performed.”27Merce Cunningham Dance Company Tour booklet. New York: Foundation for Contemporary Arts, 1963. No back-alley scrap pile was safe from being incorporated into a Story scenic tableau. Sometimes Rauschenberg, Hay, or other guests appeared onstage as integral components of the set. When Story was performed in Venice, Rauschenberg had the stagehands “move about in the background, changing props and pushing brooms.”28Brown, Chance and Circumstance, p. 385. For one of the Tokyo performances, Cage and a group of invited Japanese musicians were situated behind the dancers as they performed, reinforcing the close level of exchange that was taking place between the Japanese and American artists. Rauschenberg supplied an ever-rotating cache of costumes that the dancers could layer and remove at their own choosing. Dilley recalls:

There was a bag of costumes that Rauschenberg would fill with stuff he found in secondhand stores and shops. What I remember in the tour is that he would get rid of stuff and then go shopping and get new stuff, I think that’s one of the ways he kept himself interested. . . . When we went to that bag, we’d never know what was going to be there. Sometimes we would become familiar with something, and then it wouldn’t be there anymore. We would dress ourselves. That was my place of play within the structure.

Dilley, interview

Dilley used this place of play not only to dress herself but also to entirely disrobe, if only for a brief moment, during the first Tokyo presentation of Story. (In an earlier performance of the piece, she had donned all of the garments in the bag). While nudity was otherwise nonexistent in any of Cunningham’s works, Brown remembers, “There was nothing sensational or exhibitionist about the way she did it. She simply faced upstage, disrobed and dressed again in a mundane, matter-of-fact way—rather in the spirit of a sixties Happening.”29Brown, Chance and Circumstance, p. 439. Distinguished guests in the audience that evening included Prince Yoshinomiya, a relative of Crown Prince Takamatsunomiya, as well as an official from the American Embassy and many theater critics,30Akiyama Kuniharu, “Welcoming Merce Cunningham—Clear Beauty,” Yomiuri Shimbun, Oct. 24, 1964. yet no major scandal ensued. Instead, the shock was largely interpreted by the Japanese press as an expression of artistic freedom. The bigger revelation, as articulated by critic Oe Kenzaburo, was that the piece showed “the audience that they were free from any kind of restraints of promises and meanings.”31Kenzaburo Oe, “Watching Merce Cunningham—The Free Man on Stage,” Yomiuri Shimbun, Nov. 16, 1964. Despite the narrative structure implied by the dance’s title, Story, the work contained no coherent plot. Oe’s remark was one among many that applauded the non-narrative quality of Cunningham’s choreography, which, by relieving viewers of the obligation to project ahead to what might come next, freed them to attend to what was actually happening onstage.

Although Dilley’s gesture did not provoke public controversy, it did point toward the increasingly divergent views within the company on how far spontaneous experimentation could be pushed within the framework of a dance. While Rauschenberg was interested in testing the limits of what could arise from “the drama and the threat of being onstage, exposed, with no way to erase or change,”32Don Shewey, “We Collaborated by Postcards: An Interview with Robert Rauschenberg.” Theatre Crafts, April 1984, p. 72. Cunningham’s choreography was more self-contained. Except in isolated pieces like Story, chance and experimentation lived more within Cunningham’s choreographic process than in the delivery of the performances, themselves.

Among the responses to the company’s performances, some observers in Tokyo formed connections between Cunningham’s dances and the chaos of urban life. Architect Kurokawa Kisho wrote, “Cunningham’s work is like a modern city, where the elements exist indifferently but still stimulate each other.”33Kisho Kurokawa, “The Merce Cunningham Performance and Modern Space,” Design Magazine, 1964. Keio University Art Center Archives. There is a sense that for viewers like Kurokawa, seeing the performances transformed, even if only temporarily, the ways in which they perceived their daily surroundings. The work that Cunningham and his collaborators were pursuing had the power to invoke a heightened sense of awareness toward movement and the environment, a consciousness that could extend beyond the theater experience.

While the Sogetsu Art Center and the national daily newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun were MCDC’s official hosts in Tokyo, the company was also largely in the hands of individual artists and friends, allowing for a deeper and more varied level of engagement. Akiyama attended to Rauschenberg throughout the trip,34Ikegami, The Great Migrator, p. 155. while Ichiyanagi, Teshigahara Hiroshi, and others took care of the rest of the company. On a free evening, Teshigahara screened for the group his Academy Award–nominated film, The Woman in the Dunes, which had been released that year. At Sogetsu, Cage and Tudor performed with Ichiyanagi in an additional music concert that included works by Ichiyanagi and a piece by Toru Takemitsu, composer for The Woman in the Dunes. Nakaya Fujiko, who assisted Rauschenberg during the American artist’s event “Twenty Questions to Bob Rauschenberg” at Sogetsu35Ibid., p. 169. later became a member of Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T)36Rauschenberg was a founding member of the E.A.T. collective, along with Billy Klüver, Fred Waldhauer, and Robert Whitman. E.A.T. paired artists with engineers and scientists, and Nakaya first worked under its auspices on the Pepsi Pavilion at Expo ’70 in Osaka. and a lifelong friend of the Cunningham Company, providing vital coordination on their future tours to Japan.

Another key opportunity for artistic exchange during the tour was a US–Japan workshop that paired Rauschenberg and a selection of Cunningham’s dancers with Japanese modern dancers, musicans, and performers.37Ibid., p. 155. This public event, arranged by Akiyama and sponsored by Sogetsu, took place between MCDC’s two sets of repertory performances in Tokyo. Although there is no record of whether Cunningham was invited to participate in the event, his absence further hints at the growing divisions between his work and Rauschenberg’s initiatives. The evening was split into two programs: one that was Japanese, with artists such as Takehisa Kosugi, who became affiliated with the Fluxus movement and much later served as MCDC’s music director after Cage died, Butoh founder Hijikata Tatsumi, and the collective known as the 20th Century Dance Group,38Although Hijikata’s name appears on the program, it is uncertain whether he performed at the event, according to an unrecorded conversation with Uesaki Sen, archivist at Keio University Art Center Archives, on August 17, 2014. and the other that was American, with performance works by Rauschenberg, Steve Paxton, Alex Hay, and Deborah Hay. Rauschenberg later recalled the significance of the event: “We were moved by a team of ten painters, musicians, and dancers who put on a special concert for us. Their attitude toward dance is similar to ours—a free, close collaboration of lighting, music, costume, movement, sets.”39Grace Glueck, “Art Notes: Adventures Abroad,” New York Times, June 6, 1965. This kind of formalized performance exchange with local artists was unique to the company’s stop in Tokyo and exemplified the earnest effort that was made there to deepen the level of engagement and transmission between Japanese and American artists.

In addition to contemporary art exchanges, the MCDC also had opportunities to see traditional Japanese art forms such as Bugaku in Nara, Bunraku in Osaka, and Kabuki in Tokyo. On the afternoon of one of their final shows, Cunningham and Brown deviated from their strict pre-performance routine to see the famous onnagata (male actor playing a female role) Nakumura Utaemon in a kabuki theater piece.40David Vaughan, Merce Cunningham: 50 Years (New York: Aperture, 1997), p. 145.

THE CLOSING STAGE

Although the transience of touring life often inhibits the traveler’s ability to get to know a locale more deeply, the company was more fully embedded in Tokyo than they had been in almost any other city on their journey. At the culmination of six months spent on the road, the growth and creative evolution of the individual tour participants reached a point at which the company’s original structure was no longer viable. In the words of the tour’s administrator Lewis Lloyd, the reasons for the company’s dissolution were “very complex, as complex as the fifteen personalities involved,”41Brown, Chance and Circumstance, p. 445. yet the a final divisive misunderstanding arose when Cunningham and Cage left early from Rauschenberg’s event “20 Questions to Bob Rauschenberg.” As Cunningham described it, the anxiety surrounding the evening of the ultimate breakdown was precipitated by a misunderstanding when he left to say good-bye to dancer Viola Farber who, with the tour essentially over, was flying out on her own itinerary, separate from other members of the company:

We arrived at Sogetsu Hall after RR’s [Rauschenberg’s] program had begun. . . I sat for five minutes dwelling on VF [Farber] and then got up and left, to taxi back to the International House, rushed in to find her at dinner before taking the airport bus. It was sad talk, the end, but I could not have her, after this six-month odyssey, leave . . . without anyone to say thank-you and good-bye. She left, and I returned to Sogetsu . . . my head thick with VF; when JC [Cage] suggested leaving, I docilely agreed (it was impolite), and we left the hall.

Ibid., p. 36.

Rauschenberg responded the next day with two notes, one curt, the other more detailed, explaining that he would no longer work with the company. He articulated, “There is a basic difference in our attitudes that I think is responsible for our difficulties. I think your dances + dancing are great. I am grateful to have been able to see so much of it and be so close. I would very much like to be your friend and fan.”42Ibid A decade later, Rauschenberg wrote of the separation:

I don’t want to examine and flatten by classification, and description, a continuous moment of collaboration that exists in a group soul. Details are fickle and political and tend to destroy the total events. The rare experience of working with such exceptional people under always unique conditions and in totally unpredictable places (all acceptable because of a mutual compulsive desire to make and share) should not, by me, be shortchanged by memory or two-dimensional fact.

James Klosty, Merce Cunningham (New York: Saturday Review Press/E. P. Dutton, 1975), p. 83.

Although the company’s presence in Japan reflected a composite of extremes, Rauschenberg’s statement underscores the fundamental necessity of the endeavor and the collective spirit behind it. The enduring vitality within the group’s collaborations ultimately transcended the divisions that eventually led to its dissolution and reorganization. Japanese artists and critics advanced unique discussions around the elements of chance and indeterminacy in the company’s work and explored their relationship to Tokyo’s rapidly modernizing urban environment. Even before MCDC arrived in Tokyo, Japan was considered a critical stop on the world tour, a locale philosophically, intellectually, and creatively in tune with the collaborative approach of Cunningham, Cage, and Rauschenberg. The Sogetsu Art Center, in conjunction with individual artists and members of the Japanese avant-garde, contributed to an intensive residency featuring meaningful mutual exchange. Tokyo was the site of a confluence of decisive endings and beginnings, spurring creative growth in all the artists involved. Despite the difficulties of the journey, Cunningham said soon after returning home to New York that “he would leave again [on tour] tomorrow if given the opportunity.”43Vaughan, Merce Cunningham: 50 Years, p. 145.

Special thanks to Uesaki Sen of Keio University Art Center and Isobe Masako of the Sogetsu Foundation for assisting with the images and ephemera for this piece, and to Andy Underwood-Bultmann at the Walker Art Center for editing the interview footage.

- 1Letter from David Vaughan to Kozo Igawa, June 17, 1963. Keio University Art Center Archives.

- 2Rauschenberg resumed collaborating with Cunningham on the 1977 dance Travelogue, and subsequently designed the costumes and décor for the MCDC repertory dances Interscape (2000) and XOVER (2007), as well as Immerse (1994), a backdrop that was used for site-specific Events.

- 3Charles Greville. “The new ice-breakers of modern ballet.” Daily Mail. July 28, 1964.

- 4“Pop Ballet.” Time. August 14, 1964.

- 5A. V. Coton. “‘Anti-ballet’ presented with apologies.” Daily Telegraph. August 6, 1964.

- 6Ichiyangi Toshi, in the Sogetsu Art Center program for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, 1964. Keio University Art Center Archives.

- 7Hiroko Ikegami, The Great Migrator (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2010), p. 168.

- 8Barbara Dilley, interview with the author, June 2012. Walker Art Center Archives.

- 9Alexander Bland. “The Future Bursts In.” Observer Weekend Review. August 2, 1964.

- 10In 1956 the company toured across the United States in a Volkswagen Microbus, with all of the personnel, costumes, and sets packed snugly into the vehicle. This period marked an earlier, more familial time in the company’s history.

- 11Carolyn Brown. Chance and Circumstance (New York: Knopf. Second edition, 2008), p. 433.

- 12For more on Jikken Kobo, see https://post.moma.org/apn-portfolios-and-jikken-kobo/

- 13Brown, Chance and Circumstance, p. 118.

- 14John Cage and Joan Retallack, Musicage (Hanover, NH: Wesleyan Univ. Press, 1996), p. 52.

- 15Hiroko Ikegami, The Great Migrator (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2010), p. 162.

- 16Ibid., pp. 162–163.

- 17Ichiyanagi Toshi, interview with the author, April 26, 2013. Walker Art Center Archives.

- 18Letter from Vaughan to Igawa.

- 19Letter from John Cage to Ichiyanagi Toshi, April 22, 1963. Keio University Art Archives.

- 20David Vaughan, “Adventures on a World Tour,” New York Times, January 3, 1965.

- 21Brown, Chance and Circumstance, 2008, p. 438.

- 22Ibid., p. 376.

- 23Merce Cunningham, “Story of a Dance and a Tour. Part 3,” Dance Ink, 1994, p. 35.

- 24Brown, Chance and Circumstance, p. 438.

- 25Yoshiaki Tono, “Pop Art and Myself: An Interview with Rauschenberg,” Geijutsu Shincho, no. 182, February 1965, p. 58. Quoted in Ikegami, The Great Migrator, p. 169.

- 26Brown, Chance and Circumstance, p. 438

- 27Merce Cunningham Dance Company Tour booklet. New York: Foundation for Contemporary Arts, 1963.

- 28Brown, Chance and Circumstance, p. 385.

- 29Brown, Chance and Circumstance, p. 439.

- 30Akiyama Kuniharu, “Welcoming Merce Cunningham—Clear Beauty,” Yomiuri Shimbun, Oct. 24, 1964.

- 31Kenzaburo Oe, “Watching Merce Cunningham—The Free Man on Stage,” Yomiuri Shimbun, Nov. 16, 1964.

- 32Don Shewey, “We Collaborated by Postcards: An Interview with Robert Rauschenberg.” Theatre Crafts, April 1984, p. 72.

- 33Kisho Kurokawa, “The Merce Cunningham Performance and Modern Space,” Design Magazine, 1964. Keio University Art Center Archives.

- 34Ikegami, The Great Migrator, p. 155.

- 35Ibid., p. 169.

- 36Rauschenberg was a founding member of the E.A.T. collective, along with Billy Klüver, Fred Waldhauer, and Robert Whitman. E.A.T. paired artists with engineers and scientists, and Nakaya first worked under its auspices on the Pepsi Pavilion at Expo ’70 in Osaka.

- 37Ibid., p. 155.

- 38Although Hijikata’s name appears on the program, it is uncertain whether he performed at the event, according to an unrecorded conversation with Uesaki Sen, archivist at Keio University Art Center Archives, on August 17, 2014.

- 39Grace Glueck, “Art Notes: Adventures Abroad,” New York Times, June 6, 1965.

- 40David Vaughan, Merce Cunningham: 50 Years (New York: Aperture, 1997), p. 145.

- 41Brown, Chance and Circumstance, p. 445.

- 42Ibid

- 43Vaughan, Merce Cunningham: 50 Years, p. 145.