Was Robert Rauschenberg’s 1964 visit to Tokyo a case of cultural exchange or of cross-cultural discommunication? The question is central to this account of Gold Standard, a “combine” that Rauschenberg created during an event at Tokyo’s Sōgetsu Art Center in November of that year. Originally planned by the critic Tōno Yoshiaki as a public interview with the artist, “Twenty Questions to Bob Rauschenberg” turned into a performance as Rauschenberg ignored the questioners and went about creating a work onstage. The author vividly relates what happened during the event and examines the nature of Rauschenberg’s encounter with the Japanese avant-garde.

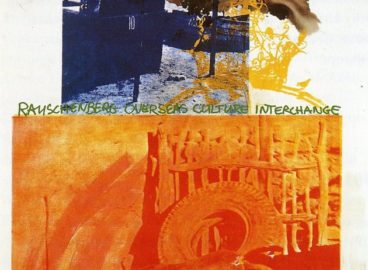

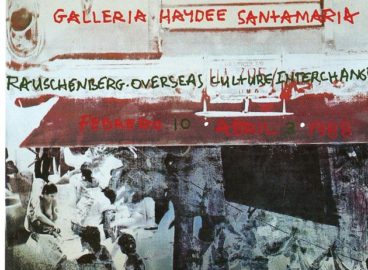

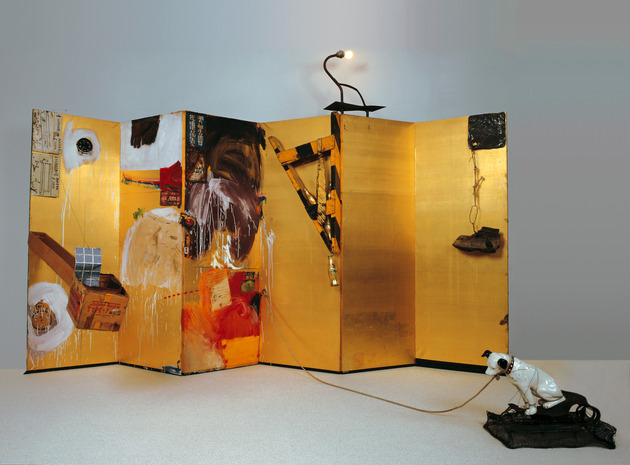

Among numerous events that involved New York artists in Tokyo in the 1960s, “Twenty Questions to Bob Rauschenberg,” which took place at the Sogetsu Art Center in November 1964, is perhaps the most legendary. It staged the public making of a work by the world-famous artist who had just received the Grand Prize at that year’s Venice Biennale. The work, Gold Standard (fig. 1), remains one of Rauschenberg’s most important “combines,” serving as testimony to the cross-cultural communication—or discommunication—that marked the artist’s first visit to Japan and setting a precedent for many of his subsequent overseas projects. This essay will examine how the theme of communication and its failure surface in the works that Rauschenberg created in Tokyo and will consider how Japanese artists strategically negotiated the presence of overwhelmingly influential American art.

“A Cool Yankee” in Tokyo

What brought Rauschenberg to Tokyo in the first place? He came to Japan as the set and costume designer for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company’s first world tour, which started in Paris in June and ended in Tokyo in November 1964, stopping in thirty cities in twelve countries in Europe and Asia. At the time of his arrival in Tokyo, Rauschenberg’s fame in Japan was at its zenith: in addition to the critic Tōno Yoshiaki’s enthusiastic promotion of post–Abstract Expressionist art since 1959,1Tōno introduced Rauschenberg, along with Jasper Johns, Yves Klein, and Jean Tinguely, to the Japanese art community for the first time in a 1959 essay in which he referred to key Rauschenberg works such as Bed, Monogram, and Erased de Kooning Drawing. See Tōno Yoshiaki, “Kyōki to sukyandaru: Katayaburi no sekai no shinjin tachi” [Madness and Scandal: Fanastic New Faces of the World], Geijutsu shinchō 10, no. 11 (November 1959), pp. 104–112. Rauschenberg had just won the Venice Biennale’s Grand Prize, a first for an American artist. The artist Shinohara Ushio2Shinohara’s “Imitation Art,” including that of Rauschenberg’s Coca-Cola Plan, is discussed in “Shinohara Ushio’s Dialogue with American Art: From Imitation Art to Pop Ukiyo-e” on this online forum. described his first impression of the American artist in Tokyo this way: “Gilt-edged sunglasses and a khaki jacket. He’s such a cool Yankee that he doesn’t quite look like a modern master. He’s dressed so well that the wannabe Ivy Leaguers in Ginza would immediately want to imitate his look.”3Shinohara Ushio, Zen’ei no michi [Avant-Garde Road], (Tokyo: Bijutsu Shuppan-sha, 1968), p. 142. Rauschenberg was thus an object of adoration as a figure who embodied not only the cutting edge art of New York but also the trendy pop culture of America.

However, it should be noted that Rauschenberg was a subject “to see” as much as an object “to be seen,” since he himself was a tourist trying to make some sense of this foreign city. Thus, Rauschenberg’s trip to Tokyo involved two intertwining gazes: the artist’s gaze upon the city as an outsider and the Japanese audience’s gaze upon the star artist from America. Although these gazes, each oriented according to its own interests and fantasies, did not quite meet and resulted in a kind of cross-cultural discommunication, Rauschenberg’s interaction with the Tokyo avant-garde offers an important case study for thinking about global modernisms.

Rauschenberg’s “Tokyo”

The first work Rauschenberg made after his arrival is a collage titled For John Cage (fig. 3). The work illustrates a printed program of events that included “Twenty Questions to Bob Rauschenberg” (originally announced as a public interview) and a concert by John Cage and David Tudor. The ground of this collage is an aerial photograph of Shinjuku, a recently redeveloped subcenter of Tokyo, where the Shinjuku Station on the Keio train line opened in 1963 and the Keio Department Store opened in 1964. Rauschenberg seems to have found this image on a postcard or in a brochure for tourists.

To create the work, Rauschenberg pasted words and phrases cut out from a phrase book onto the photographic image of the sky over Shinjuku.4Nakaya Fujiko, interview with the author, July 31, 2003, Tokyo. Japanese language fragments sprinkled over the picture form several groups—individual words on the left, conversations for tourists on the top and bottom, and maxims and sayings on the right—but do not make logical sense as a whole, thereby creating the kind of linguistic chaos that a tourist might feel in a foreign city. In addition, the cityscape of Tokyo had a new look at the time. The Olympic Games had just taken place there in October, in preparation for which the Japanese government had constructed the Olympic roads and the Tokyo Metropolitan Expressway to receive throngs of international guests. Rauschenberg’s eyes thus adroitly responded to a city that had just undergone the first stage of modernization.

Since phrase books are usually bilingual, Rauschenberg must have known what those snippets of Japanese meant in English. However, those words and phrases, “suspended” without speech subjects, do not form a coherent statement. Rather, as the work’s title For John Cage suggests, the linguistic syncopation that visually pulses over the image of Tokyo functions as Cagean urban noise. Its syncopated rhythm actually corresponds to Rauschenberg’s description of the city as “staccato,” the word he used when Tōno asked about his impression of the city.5Tōno Yoshiaki, “Poppu āto to watashi: Raushenbāgu” [Pop Art and Myself: An Interview with Rauschenberg], Geijutsu shinchō, no. 182 (February 1965), p. 58. Rauschenberg thus gave visual form to his first impression of Tokyo and presented it as a greeting card to the Japanese audience.

However, in contrast to Cage, who was very learned about Japanese culture and aesthetics, Rauschenberg seems to have accepted the fact that he was a mere traveler through Tokyo and mocks the tourist’s fantasy of having a firsthand experience of the cultural other. The fact that he cut up a phrase book (originally meant for a tourist such as himself) and rendered it useless can be seen as an indication of his skepticism about cross-cultural communication, which is, in fact, often mediated by such standardized guidebooks.

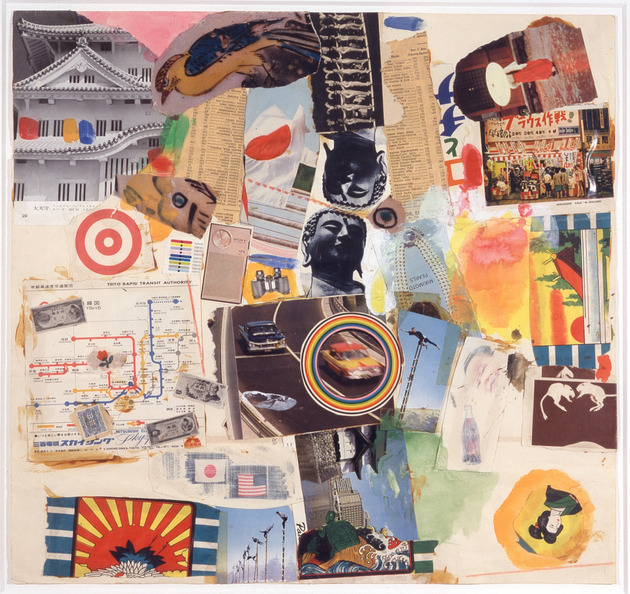

But since he was an artist as well as a tourist, Rauschenberg was not free from the problematics of representing the cultural other. A look at Tokyo (fig. 4), a collage he created for Japan’s leading newspaper, Yomiuri shimbun, provides quite a different take on the city. For this work, Rauschenberg cut out illustrations from popular magazines and other readily available sources, juxtaposing traditional and modern aspects of Tokyo. While images of Buddha, a castle, and a scene of acrobatics are included as exotic features, pictures of highways, a subway map, and a discount sale convey a sense of a busy and modern urban atmosphere. This seemingly simplistic juxtaposition of the old and new in the Japanese metropolis was not meant to be a complete work in itself. Yomiuri shimbun had originally commissioned Rauschenberg to write an essay on Tokyo and to pair it with a collage. But the artist came up with a plan of his own and requested that the work be printed on the newspaper’s front page. As he explained to Tōno, “I wanted the surrounding articles to be printed in color as well, as opposed to the regular black ink. I wanted one article printed in blue, the other in red, and the editorial in yellow. . . .”6Ibid.

Surprisingly, this unorthodox request was initially approved by the company. The artist, who said that he would consider the work complete only in its final stage (that is, when printed in the newspaper), told Tōno: “I have no idea how it will turn out. Nobody knows what kind of news will be published nor is it possible to predict what kind of color it will be finally printed in. But the whole page—including articles—would be my essay on Tokyo.”7Ibid.

Commenting on the democratic significance of the work’s appearing in a newspaper and being distributed as such, he praised Yomiuri shimbun for taking on such a bold project: “When it’s printed, people would open the newspaper as they normally do, read the colored news of the day, and also read a work of art. Wouldn’t that be wonderful? It would not be just a thing that belongs to just art fans anymore, but it would be a thing that is just there. . . . You might think I’m crazy to ask such an outrageous thing of a big newspaper company, but it’s great that it was accepted. It could never happen with the New York Times.”8Ibid.

As a matter of fact, it could never happen with Yomiuri shimbun either; the company eventually canceled the project. Let us consider the reason why by imagining the way Tokyo might have actually appeared in the newspaper. In early December 1964, right after Rauschenberg left Tokyo to return to New York, the Japanese daily’s front page was filled with a variety of articles on foreign affairs. Topics included Japan’s diplomatic issues with South Korea and China, America’s bombing of Vietnam, and developments in space exploration. Surrounded by international news, Rauschenberg’s Tokyo would have stood out as a local news item. Moreover, with articles printed in different colors, the page would have had an interesting visual effect analogous to the monitor of a color television.

However, the work would also have posed many problems, for Rauschenberg would have transformed what Marshall McLuhan once acclaimed as “a collective work of art,”9Marshall McLuhan, The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man (Corte Madera, CA: Gingko Press, 2002), p. 3. First published in 1951. that is, the front page of a newspaper, into his own artwork. Delivered as the production of a single artist, the page would have lost its collective nature and objective neutrality—the fundamental principles of major newspapers—and become something literally “colored” by the artist’s subjectivity. The statements quoted above indicate that, as far as this project was concerned, Tokyo was for Rauschenberg a marvelous place, where he could achieve things he would not have been able to at home. Juxtaposed with an article on the bombing of Vietnam, Rauschenberg’s “essay on Tokyo” inevitably would have revealed the artist’s utopian or even colonial optimism by literally invading, if unintentionally, the sphere of public discourse in a foreign land. This issue would resurface on the stage of “Twenty Questions to Bob Rauschenberg” at the Sogetsu Art Center.

“Twenty Questions to Bob Rauschenberg”

It is well-known that Gold Standard was created during “Twenty Questions to Bob Rauschenberg,” the now legendary event organized by the critic Tōno. But just how did the program, originally announced as a public interview with the artist, turn into a performance-like production of the work? According to Rauschenberg’s longtime friend, the artist Nakaya Fujiko, it was Teshigahara Sōfū, a sponsor of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company’s tour in Japan, who prompted Rauschenberg to produce a work on a gold screen. Sōfū held a party one night for the entire troupe at a high-class, traditional Japanese-style restaurant. On that occasion, Sōfū told Rauschenberg about a Japanese custom—although no longer commonly practiced—whereby a guest would paint a picture or write a piece of calligraphy for his host as a token of gratitude. Seeing that Rauschenberg was inspired by the story, Sōfū offered him a gold folding screen, which the artist decided to use in his public interview appearance at the Sogetsu Art Center, since he was not really interested in the ordinary interview that was slated.10Nakaya Fujiko, interview with the author, July 31, 2003, Tokyo.

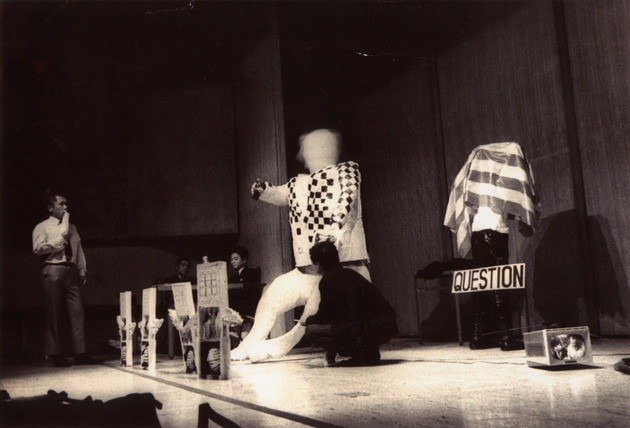

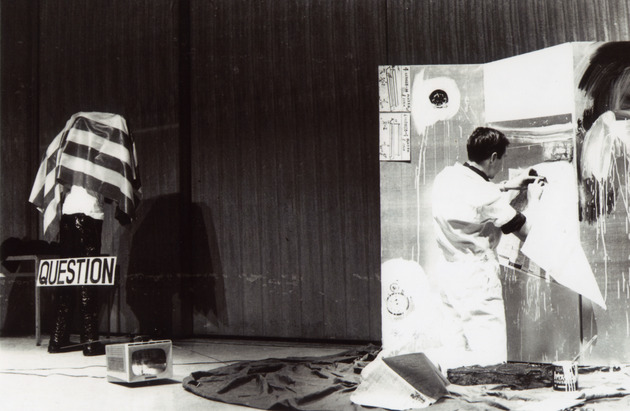

The program began on schedule on November 28, 1964, with Rauschenberg working on the screen with Alex Hay, his technical assistant during the dance company’s world tour (figs. 5). First, they removed the black frame from the upper edge of the screen to create a kind of free, open space. This was a typical gesture for Rauschenberg, who always presented his work as an open field with which a viewer could be engaged. He then accented its surface with paint while Hay affixed to it a road barrier from a local construction site. After splashing black and white paint over the screen, Rauschenberg went on to attach items such as a speedometer, a clock, Coca-Cola bottles, and a gold-painted necktie—all typically Rauschenbergian objects—while also creating an improvisational transfer drawing with a page from the Japan Times.

While the baffled audience looked on politely, the critic Tōno, who had known what would occur, enacted his own “happening.” He created questions by appropriating published statements by Rauschenberg and various critics who had written about his work. Thus, the artist’s famous utterance—“Painting relates to both art and life. Neither can be made. (I try to act in the gap between the two)”11Robert Rauschenberg, “Statement,” in Dorothy Miller, ed., Sixteen Americans (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1959), p. 58. —was turned into: “Does painting relate to both art and life? Can neither be made? Do you try to act in the gap between the two?” When Tōno uttered his questions, however, the audience was unable to decipher what he was saying because his speech was channeled through an electronic sound distorter made by the composer Ichiyanagi Toshi (who had studied with Cage in New York in the 1950s) and reached the audience as noise. Although this was the critic’s attempt to treat his own medium—words and logic, that is—as readymade material with which to create a kind of linguistic “combine,” the idea was not clearly communicated to the audience, whose incomprehension was thereby doubled.

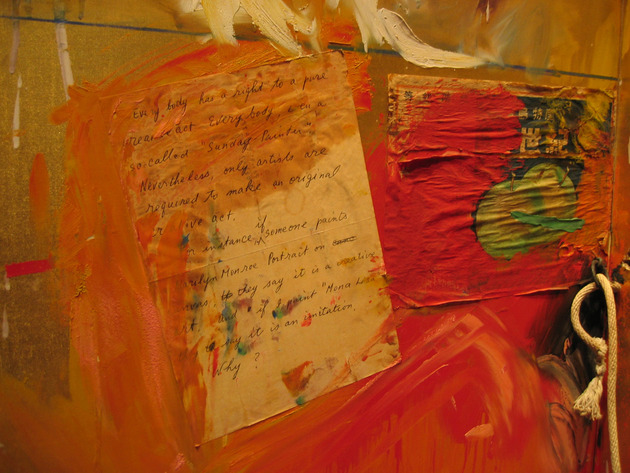

In addition, Tōno had invited Shinohara and the artist Kojima Nobuaki to pose questions to Rauschenberg directly. When Tōno raised his hand twice, as arranged, the two went up on the stage with Shinohara’s work Marcel Duchamp in Thought and imitations of Coca-Cola Plan, and also Standing Figure (known as “Man with a Flag”) by Kojima, which held a placard that said “QUESTION” (fig. 6). Shinohara read out his questions in Japanese and in English with the help of the interpreter Takashina Shūji, a leading art critic and, at the time, a curator at the National Museum of Western Art. According to Takashina, Rauschenberg reflexively looked back when addressed by the interpreter as “Mr. Rauschenberg,” but immediately returned to work when he recognized that it was a question.12Takashina Shūji, interview with the author, August 8, 2003, Ōhara Art Museum, Kurashiki. Frustrated, Shinohara placed at Rauschenberg’s feet a sheet of paper bearing a translated question, which the artist then pasted onto the gold screen (fig. 7). He went on to complete the work by attaching additional objects, such as a cardboard box from Sony, a worn-out pair of leather shoes, an electric light, and, at the end of a leash-like rope, a ceramic figure of the Japan Victor dog (identical to the RCA Victor dog and retained as a mascot when the Japanese branch of the business split off from the American company at the beginning of World War II). When the piece was finally completed, more than four hours had passed.

The resulting work, Gold Standard, created on a stage where verbal communication was blocked, looks like an arena in which Rauschenberg’s gestures were carefully improvised to achieve a fine balance between the traditional opulence of the gold screen and the objects salvaged from the streets of Tokyo. Indeed, such high-contrast juxtaposition of the traditional and the modern was (and still is) what makes Japan attractive as a tourist destination: it is timeless and traditional, but with the familiarities and comforts of modern urban life. Rauschenberg’s work thus predicted the stereotypical image of Japan as a country where tradition and technology coexist without friction. The Japan Victor dog, seated on a bicycle saddle and tied to the gold screen, seems quite lost in this rather disorienting symbolic landscape of Tokyo. With its quizzical expression and inclined head, the figure reads as a kind of surrogate tourist in an unfamiliar place—where a clear order, let alone “His Master’s Voice,” does not exist.

In a later interview with Tōno, Rauschenberg said that he “had tried very hard not to answer any questions during the program because that would have entirely changed the significance of the whole event.”13Tōno Yoshiaki, “Raushenbāgu, kono itten: Gōrudo sutandādo” [This Work by Rauschenberg—Gold Standard], Bijutsu techō, no. 294 (February 1968), p. 66. Tōno paraphrased what the artist said as follows: “What is dialogue anyway? . . . Can you just call it a dialogue or interview if a critic and an artist discuss issues with words and the artist states his opinion? Maybe there is a trap in that idea, a trap that you somehow assume you will be understood after all. I do wonder if communication should make such coherent sense. . . .”14Ibid., p. 65. Given Rauschenberg’s distrust of words as vehicles for communication, it cannot have been by coincidence that he pasted the Japanese saying Fugen Jikkou (which corresponds to the English aphorism, “Actions speak louder than words”)—in the middle of the collage For John Cage. The confusion of the Victor dog would therefore seem not to reflect the state of Rauschenberg the performer, for it was he who chose not to employ speech onstage. Rather, it mirrors the resulting discommunication and the puzzlement of other participants and the audience, who were denied any sort of verbal exchange with the artist.

Cross-Cultural Discommunication in Gold Standard

Yet Rauschenberg’s creation of Gold Standard was not entirely silent; it was accompanied by image and sound from a small television that played onstage during the entire program, as if to make up for the absence of verbal interaction (fig. 8). The TV functioned as a formal element of the performance, as a modern screen emanating light from within, in contrast to the traditional gold screen, which reflected light from outside. Moreover, according to Nakaya, putting the TV onstage was Rauschenberg’s “path of least resistance” to the pressure of making a work in public.15Nakaya Fujiko, interview with the author, July 31, 2003, Tokyo The television, a tool of mass communication, was intended to keep Rauschenberg company during the production as well as to mediate between the artist and the audience. It is an ironic fact of the cultural exchange that Rauschenberg, anxious about his stage performance, felt more at ease with a TV than with his “foreign” audience.

However, I would venture to argue that Rauschenberg’s anxiety was more than just stage fright. It is highly possible that he also feared his own role as a model to be imitated. In The Location of Culture, Homi K. Bhabha theorizes the logic of mimicry as a strategy to challenge colonial authority, taking the example of localized usage of the Bible in colonial India.16Homi K. Bhabha, “Signs Taken for Wonders,” in The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994), pp. 102–122. Similarly, the rather uncanny sight of Rauschenberg surrounded by Shinohara’s imitations of his work and Kojima’s figure enveloped in a cloth resembling the U.S. flag17Kojima claims that his initial interest was in the formal play of hide-and-seek between the cloth and the figure’s ever-invisible head. But the uncanny quality of the blinded figure has been interpreted to represent the oppressive presence of America in postwar Japan. Kojima Nobuaki, interview with the author, December 19, 2003, Tokyo. seems to point to a kind of postcolonial paradox at work in Tokyo, where the impact of American art and culture was so immense in the postwar years that it amounted to cultural colonialism. It should be recalled at this point that Rauschenberg himself had been critical of the myth of originality since the late 1950s, with works such as Factum I and Factum II (both 1957). Rauschenberg’s “fear” thus must have encompassed his discomfort at being imitated by the cultural other, an act that would position him as the orthodox and “original” figure of modern art.

The title of the work, Gold Standard, must be closely read as well. As an economic term, it refers to the system of using the value of gold as the standard on which to base the value of money. The title thus implies that there is a foundational standard in this work as well. Rauschenberg chose this title “first of all, because it [the work] is gold, and second of all, because it stands, and also because I think this work is the standard itself.”18Tōno, “Pop Art and Myself,” p. 59. Judging from this statement, the title seems to imply that the standard was the artist’s belief in his own artistic capacity, which enabled him to complete the work despite the anxiety he suffered onstage. Beyond this, the title reads as another reference to the cultural and economic hegemony of postwar America: as we know, the gold standard under the Bretton Woods Agreement of 1948 was in fact the gold-dollar standard, in which U.S. dollars, as the privileged international currency, had the same exchange value as gold.

However, the gold-dollar standard was not unshakable, since its stability depended upon the steady growth of the American economy. In reality, as the economist Milton Gilbert warned in 1968, it was becoming increasingly clear by the mid-1960s that the system would become untenable because of the ever-increasing outflow of U.S. dollars to the country’s military involvement in Vietnam.19Milton Gilbert, “The Gold-Dollar System: Condition of Equilibrium and the Price of Gold,” in Barry Eichengreen and Marc Flandreau, ed., The Gold Standard in Theory and History (London: Routledge, 1997), pp. 291–312. Originally published in 1968. Just as Rauschenberg’s authority as the cultural superior was brought into question onstage in Tokyo, the very paradigm symbolized by the gold standard in the postwar world—that is, Pax Americana—was starting to crumble.

It remains unknown whether Rauschenberg was aware of the ironic implications of his title. Nonetheless, it seems highly significant that he refused to be “lost in translation” in this situation and presented the screen and sound of the TV as “the master’s voice” for the event, where the very notion of communication was put into question. Seen in this light, the TV stands in for the ultimate failure of communication not only in the verbal and mass-mediated realms, but also, disquietingly, in art as well. For the TV onstage seems to proclaim that, with the arrival of the “society of the spectacle,” TV might replace art as a universal tool of communication: watching TV should be as good as watching Rauschenberg’s live performance.

Japan was just taking its first steps toward becoming such a society, since color television became a common household feature in most households on the occasion of the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games. The international sports festival arguably transformed Japan’s capital into a newly made city. The government had not only constructed the inner-city highways, but also employed every means to clean up Tokyo before the start of the Olympic Games, which presented Japan with the first opportunity to show its face to the international community since the country’s defeat in World War II. The collective obsession to beautify Tokyo was so intense that it became the object of mockery: the artists’ group Hi Red Center organized a work called Cleaning Event, in which performers disguised as public sanitation workers obsessively and impeccably cleaned a street in the Ginza district, using dusters and toothbrushes (fig. 9).

This situation explains why the two right-hand panels of Gold Standard are relatively empty except for an electric light and a pair of old shoes dangling from the top. Rauschenberg actually had difficulty scavenging materials from which to make his work in a city so clean and devoid of litter; he ran out of objects to complete the last two panels of Gold Standard.20Nakaya Fujiko, interview with the author, July 31, 2003, Tokyo. As a result, these last two panels bear the traces of Rauschenberg and Hay’s almost tautological gestures: the artist and his assistant added a layer of gold leaf to the lower part of the fifth panel and then painted a black bar above the black frame of the bottom edge of the sixth panel. In this context, a street sign that Rauschenberg attached to the top of the third panel from the left reads ironically. It says, “Let’s start by making a hygienic environment in order to construct a bright city” (fig. 10).

As in the two collages discussed earlier, Rauschenberg responded to what he saw in Tokyo in Gold Standard, with a clear awareness of his status as a tourist passing through. Thus, the work is another of Rauschenberg’s deliberately touristic views of Tokyo, in which the artist does not claim an authentic experience or profound understanding of the cultural other—because he is aware that any communication could be just another form of miscommunication.

A question remains: did Gold Standard become Rauschenberg’s parting gift to the host Sōfū Teshigahara? In fact, the work turned out to be a serious case of cultural misunderstanding. While Rauschenberg assumed that Sōfū would purchase the piece before Rauschenberg returned to New York, Sōfū expected the artist to present it to him as a gift for sponsoring the Cunningham Company. After some negotiation, the work entered Sōfū’s art collection, later becoming one of the key works in the collection of the Sōgetsu Art Museum.21The Sōgetsu Art Museum opened on the sixth and seventh floors of Sōgetsu Hall in 1981. It closed in 2003. It remained there until a financial crisis in the early 2000s forced the Sōgetsu Foundation to sell the work and close the museum. Now Gold Standard is in a private collection in the United States, after having been sold from a commercial gallery in Tokyo to one in New York. In today’s globalized and speculative art market, the name of Rauschenberg is an established brand, functioning as a “standard” that sets the high price of his work, which perhaps adds another layer of irony to the work’s title.

This text is based on chapter four of Hiroko Ikegami’s The Great Migrator: Robert Rauschenberg and the Global Rise of American Art (Cambridge, MA.: The MIT Press, 2010) and has been revised and abridged by the author for post.

- 1Tōno introduced Rauschenberg, along with Jasper Johns, Yves Klein, and Jean Tinguely, to the Japanese art community for the first time in a 1959 essay in which he referred to key Rauschenberg works such as Bed, Monogram, and Erased de Kooning Drawing. See Tōno Yoshiaki, “Kyōki to sukyandaru: Katayaburi no sekai no shinjin tachi” [Madness and Scandal: Fanastic New Faces of the World], Geijutsu shinchō 10, no. 11 (November 1959), pp. 104–112.

- 2Shinohara’s “Imitation Art,” including that of Rauschenberg’s Coca-Cola Plan, is discussed in “Shinohara Ushio’s Dialogue with American Art: From Imitation Art to Pop Ukiyo-e” on this online forum.

- 3Shinohara Ushio, Zen’ei no michi [Avant-Garde Road], (Tokyo: Bijutsu Shuppan-sha, 1968), p. 142.

- 4Nakaya Fujiko, interview with the author, July 31, 2003, Tokyo.

- 5Tōno Yoshiaki, “Poppu āto to watashi: Raushenbāgu” [Pop Art and Myself: An Interview with Rauschenberg], Geijutsu shinchō, no. 182 (February 1965), p. 58.

- 6Ibid.

- 7Ibid.

- 8Ibid.

- 9Marshall McLuhan, The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man (Corte Madera, CA: Gingko Press, 2002), p. 3. First published in 1951.

- 10Nakaya Fujiko, interview with the author, July 31, 2003, Tokyo.

- 11Robert Rauschenberg, “Statement,” in Dorothy Miller, ed., Sixteen Americans (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1959), p. 58.

- 12Takashina Shūji, interview with the author, August 8, 2003, Ōhara Art Museum, Kurashiki.

- 13Tōno Yoshiaki, “Raushenbāgu, kono itten: Gōrudo sutandādo” [This Work by Rauschenberg—Gold Standard], Bijutsu techō, no. 294 (February 1968), p. 66.

- 14Ibid., p. 65.

- 15Nakaya Fujiko, interview with the author, July 31, 2003, Tokyo

- 16Homi K. Bhabha, “Signs Taken for Wonders,” in The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994), pp. 102–122.

- 17Kojima claims that his initial interest was in the formal play of hide-and-seek between the cloth and the figure’s ever-invisible head. But the uncanny quality of the blinded figure has been interpreted to represent the oppressive presence of America in postwar Japan. Kojima Nobuaki, interview with the author, December 19, 2003, Tokyo.

- 18Tōno, “Pop Art and Myself,” p. 59.

- 19Milton Gilbert, “The Gold-Dollar System: Condition of Equilibrium and the Price of Gold,” in Barry Eichengreen and Marc Flandreau, ed., The Gold Standard in Theory and History (London: Routledge, 1997), pp. 291–312. Originally published in 1968.

- 20Nakaya Fujiko, interview with the author, July 31, 2003, Tokyo.

- 21The Sōgetsu Art Museum opened on the sixth and seventh floors of Sōgetsu Hall in 1981. It closed in 2003.