Performance’s only life is in the present. Performance cannot be saved, recorded, documented, or otherwise participate in the circulation of representations of representations: once it does so, it becomes something other than performance.

—Peggy Phelan

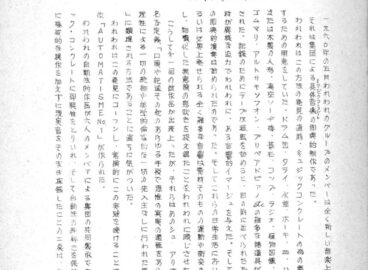

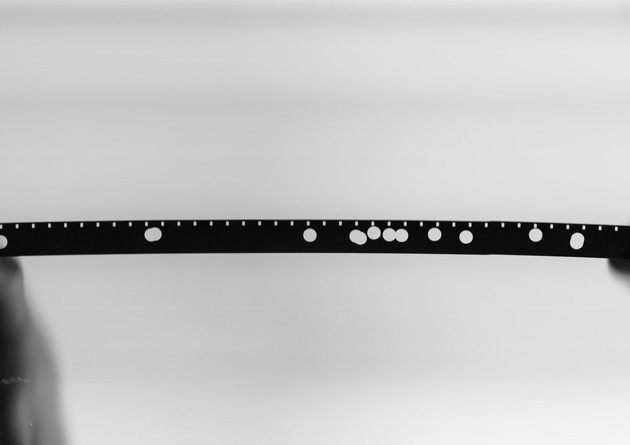

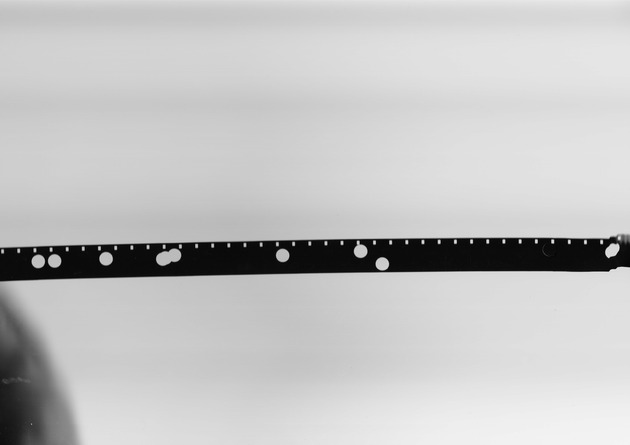

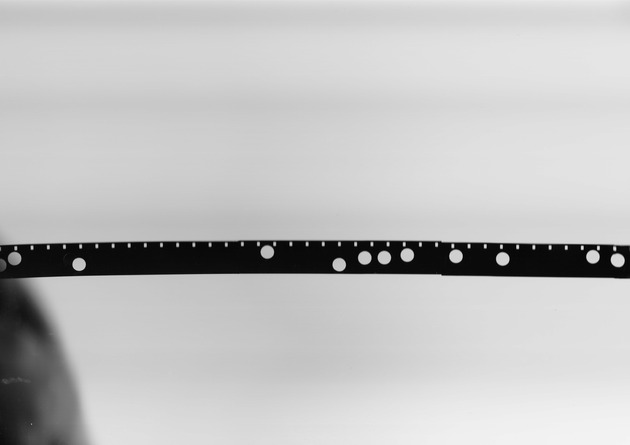

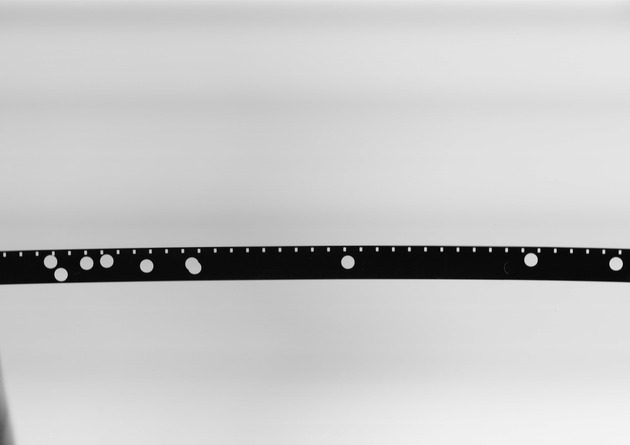

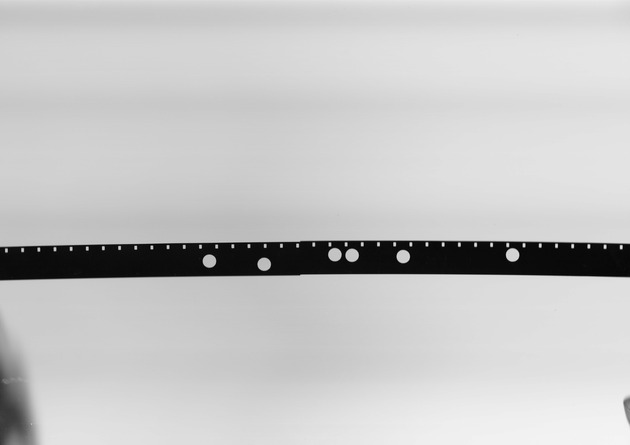

Figures 1–6 are scans of what remains of Circle & Square, performed at LUX in London on the October 13, 2003, by Iimura Takahiko. Try clicking sideways and then back again.

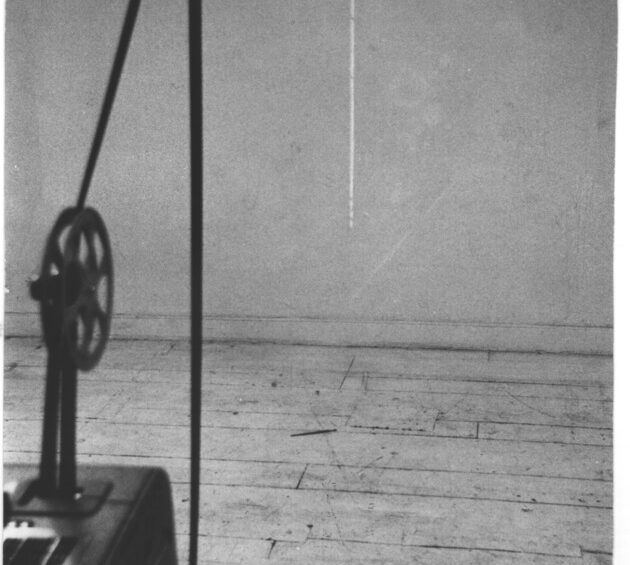

A black film leader pierced with holes is what we see when looking at the filmstrip today. What the audience saw, when it was incorporated into a performance, was something quite different. The filmstrip was looped through a hook in the ceiling and into a film projector at the back of the room. On the screen, circles of white light appeared as Iimura perforated the filmstrip with a hole puncher. The clicking sounds produced by the hole-punching operation could be heard over the buzzing of the projector. The white circles accumulated as the performance continued until finally Iimura punched one hole too many, and, after a final spin around the room, the filmstrip fell to the floor, leaving a white square on the screen at the front.

Beyond the Screen

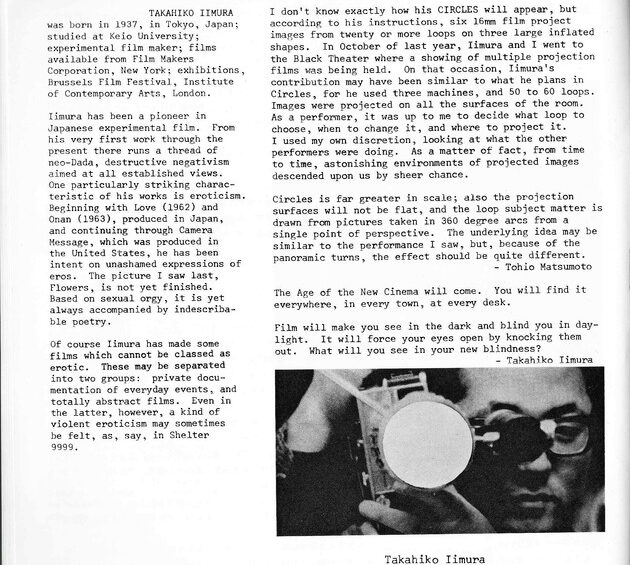

“Film actions” is the term Iimura used to describe his film presentations during a Q&A held after a screening at Theatre Scorpio in Shinjuku in 1970.1Oshima Tatsuo refers to Iimura’s screening at Sasori-za (Theatre Scorpio), where he repeatedly referred to his own presentations as “film actions” in the Q&A session on February 20,1970, as part of the Iimura Takahiko: Cinema Love-In program. (Oshima, Tatsuo. “Eizo no Umareru Chitai: Iimura Takahiko to Arakawa Shusaku no Eiga Sakuhin o Mite,” SD (Space Design), 72 [October 1970]: 104.) By then, Iimura had been engaging in alternative modes of film projection for almost a decade, seeking surfaces other than the screen for his images. Channeling a performative impulse and a resistance to institutional frameworks, he screened his films in galleries, gymnasiums, and churches and onto ceilings, balloons, and bodies. Frustrated with filmmakers’ persistent focus on recording, which led to their neglect of presentation, Iimura declared that “the screening is the first occasion where film as expression unfolds.”2Iimura Takahiko, “Imeji no Comyuniti” (Community of Images), Kikan Firumu 2, (February 1969): p. 153. He regarded screenings as opportunities to communicate with his audience and, in the case of collaborative works, with other artists. His desire for such encounters culminated in a series of film performances that reveal Iimura as a pioneer in seeking unconventional approaches to moving image presentation and a proponent of new methods for film exhibition. Iimura’s commitment to testing the limits of film while engaging with the specificities of the medium itself is most apparent in his experiments in film performance.

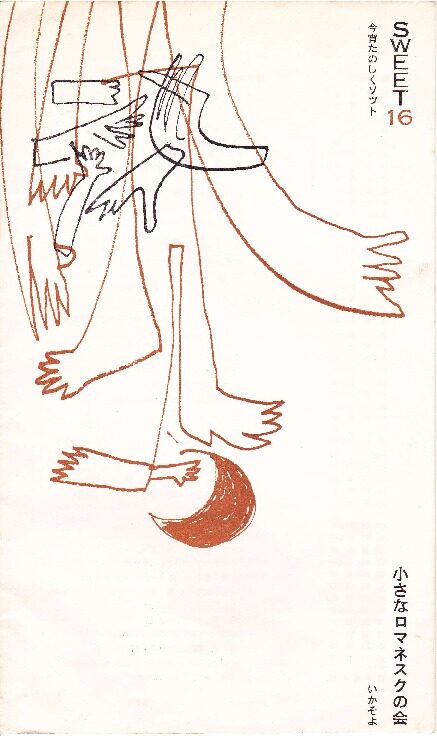

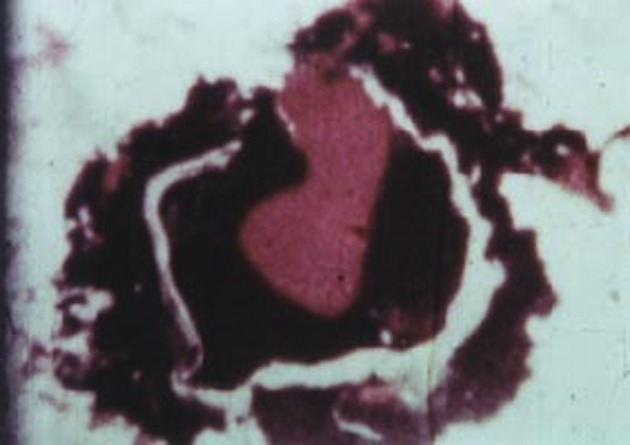

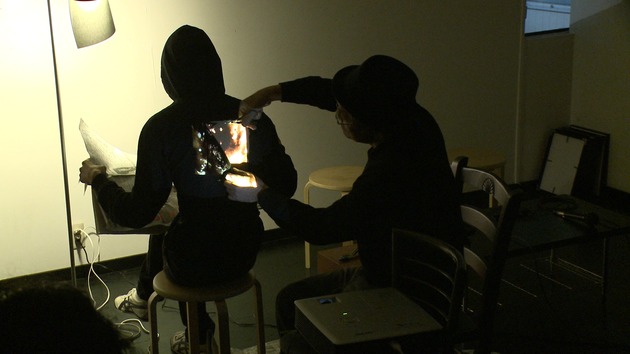

Searching for an alternative to the cinema screen, Iimura discovered the antithesis of that rigid fixed frame in human skin and the movement of the body it encases. Billed as a performance event, Sweet 16 was held at the Sogetsu Art Center December 3 to 5, 1963 (Fig. 7). Iimura was the only filmmaker on the program. He presented Screen Play, a projection of his abstract film Iro (Color, 1963) on the back of Takamatsu Jiro, a member of Hi Red Center (Fig. 8).3Hi Red Center was a performance group active from 1963 to ’64. Members included Takamatsu Jiro, Akasegawa Genpei, and Nakanishi Natsuyuki, as well as occasional guests. They often performed in public spaces but also exhibited in art galleries such as the Naiqua Gallery, where Iimura Takahiko’s works were screened. Hi Red Center’s members later became associated with Fluxus. Iro, a recording of chemical reactions concocted when paints are dropped into oil, is devoid of conventional modes of action or narrative. It encourages the audience to focus on the presence of the image rather than on what has been recorded. Iimura reportedly cut a square hole in Takamatsu’s jacket during the performance so that the film was projected directly onto his naked back while he sat between the stage and the audience, reading a newspaper (Fig. 9).4Akasegawa Genpei, however, claims that he cut Takamatsu Jiro’s jacket in the shape of the projected image. See Akasegawa, Genpei, Tokyo Mikisa Keikaku: Hi Red Center Chokusetsu Kodo no Kiroku (Tokyo Mixer Plan: Records of Hi Red Center’s Direct Actions) (Tokyo: Chikuma, 1994), p. 353. Iimura’s rejection of the Sogetsu Art Center’s eminently serviceable stage and screen was all the more pronounced as Takamatsu sat between the stage and the audience reading a newspaper, apparently oblivious to the spectacle unfolding behind him.

In an essay about Tatsuki Yoshihiro’s nude photographs, Iimura commented that in contrast to objects, the naked body (ratai) renders words inefficient due to, in his words, “its overpowering visuality.” 5Iimura Takahiko (1969). “Tatsuki Yoshihiro Shashi-ten nado: Hadaka ni tsuite (Tatsuki Yoshihiro’s Photography Exhibition: On Naked Bodies),” SD (Space Design), 65 (March): p. 109. Rather than seeing the naked body as flesh (nikutai), Iimura suggests Japan has historically conceived of the body as a figure (keishi) in pictorial representations, and he traced the tradition from traditional Japanese woodcut prints, ukiyo-e, to Tatsuki’s photography. As we can see in Ai (Love, 1963) and his film performances, Iimura attempts to show the body as nikutai: corporeal and carnal (Fig. 10). The projection onto skin illuminates the body, serving to highlight—beyond any figural characteristics—its irreducibility.6 After relocating to New York in 1966, Iimura participated in the 5th Avant-Garde Festival (1967), where he projected his films onto the face of Charlotte Moorman and other artists while they performed, attesting to his desire to forge new relationships and attain unexpected results with his films. See Iimura Takahiko, “Involuvumento – Aruiwa Jiden” (Involvement – In Account of One’s Life) in Bijutsu Techo, 327 (May 1970): p. 179. Projections onto the body became familiar offerings on Tokyo’s art scene in performances that included Jonouchi Motoharu’s Gewaltopia at Runami Gallery (1967), Yamaguchi Katsuhiro’s Lulu (1967), Tachimi Tadahiro’s Psychedelic Show (1968) at Modern Art in Shinjuku, in a pink film Buru Firumu no Onna (Blue Film Woman, Mukai Kan, 1969), and in films produced and/or distributed by the Art Theater Guild: Hatsukoi: Jigoku-hen (Inferno of First Love, Hani Susumu, 1969), Erosu purasu Gyakusatsu (Eros Plus Massacre, Yoshida Kiju, 1969), Tokyo Senso Sengo Hiwa, (The Man Who Put His Will on Film, Oshima Nagisa, 1970).

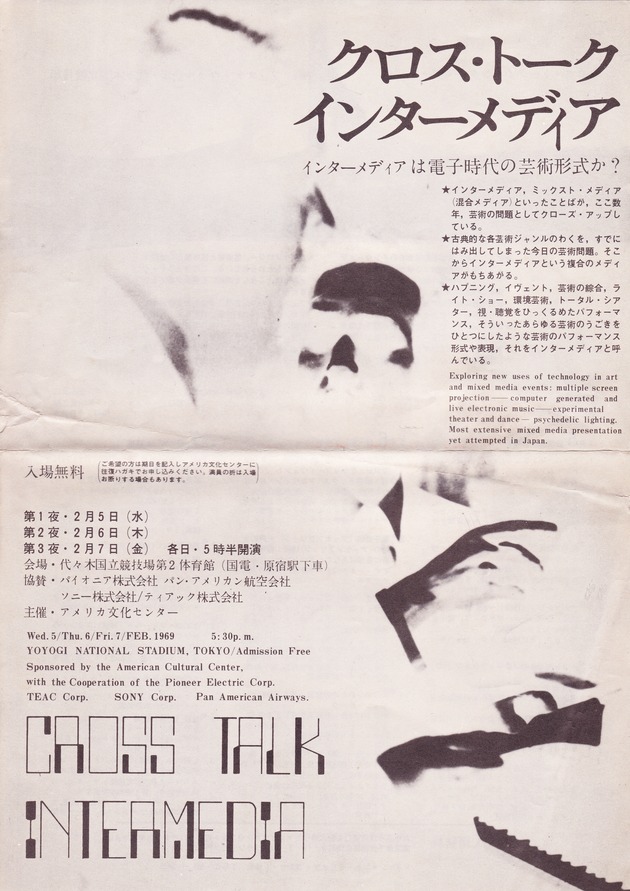

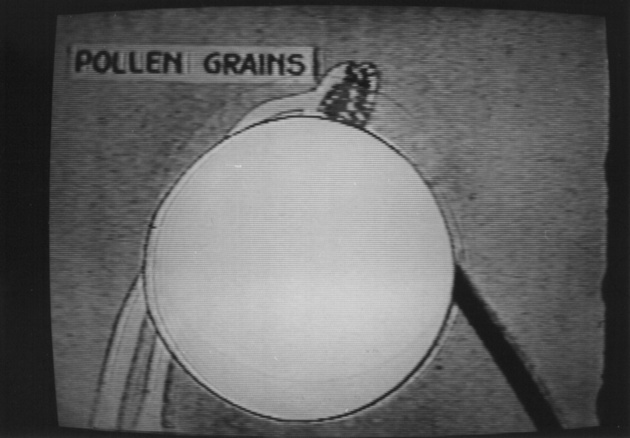

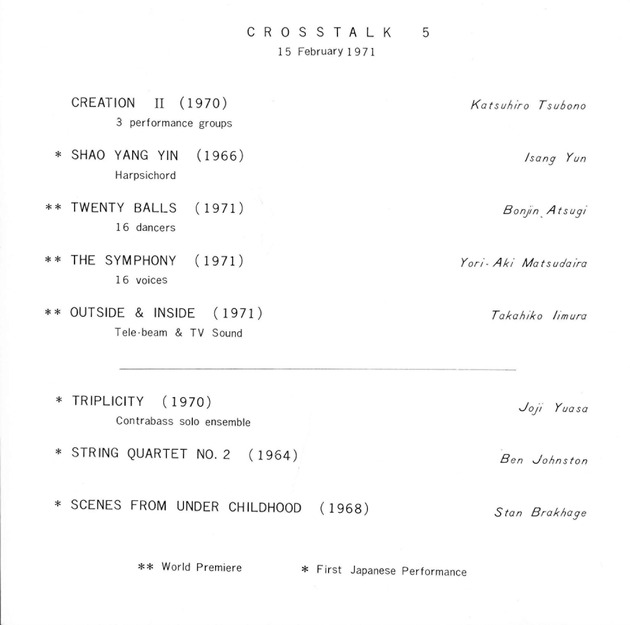

Continuing to eschew the screen, Iimura had his Circles piece projected onto spherical objects at Cross Talk Intermedia in February 1969 (Fig. 11).7Cross Talk Intermedia was the fourth event of the Cross Talk series organized by the American Cultural Center to foster collaboration between Japanese and American artists working primarily in the field of music. Spearheaded by Roger Reynolds and Kuniharu Akiyama, the event was unique in the series for its focus on expanded cinema. Participants included Stan VanDerBeek, Alvin Lucier, Robert Ashley, George Cacioppo, Salvatore Martirano, Gordon Mumma, Ronald Nameth, David Rosenboom, Ichiyanagi Toshi, Matsumoto Toshio, Yuasa Joji, Takemitsu Toru, Kosugi Takehisa and Shiomi Mieko. Iimura’s Circles was performed on February 6, 1969, using the same balloons made by Shinohara Ushio for Matsumoto Toshio’s Projection for Icon. He was unable to attend but sent instructions for six 16mm projectors to project more than 20 loop-films onto three large inflated objects, accompanied by Alvin Lucier’s Sound Environment Mixtures, a recording made with a shotgun microphone that rotated on a 360-degree horizontal arc (Fig. 12). Iimura’s loop-films all showed the same image: a 360-degree pan of the view from a street corner (Fig. 13). The footage was shot specifically for the performance in order to echo the circularity of the Cross Talk Intermedia venue, the Yoyogi National Gymnasium. Although the choice of balloons as a surface for projection had become commonplace in expanded cinema of the United States and Japan, Iimura had expressed his interest in projecting onto spherical objects as early as 1963 in a short essay published to coincide with his performance of Screen Play. In rejection of its immobility and rigid geometry, Iimura substituted the screen with balloons and bodies to rejuvenate the image in the moment of projection.8The use of balloons had been gaining popularity among Japanese artists such as Kazakura Sho, Isobe Yukihisa, and Onishi Seiji, who found in the spherical objects an alternative to the fixed position imposed by the frame conventionally found in exhibitions. Kazakura, at the “Intermedia” event at Runami Gallery, May 23 to 28, 1967, threw balloons into the gallery space during one of the screenings as a performative interruption, marking the first encounter between film projection and balloons in Japan, Other than Kazakura’s, Matsumoto’s and Iimura’s works that have already been mentioned, Azuchi Shuzo Gulliver and Yoshizawa Toshimi with Ishii Kahoru also took part in events that involved projections onto balloons. Balloons had also become a common feature internationally in performative situations such as Robert Whitman’s Two Holes of Water, No. 2 (1966), which Iimura reviewed in an article for Eiga Hyoron. Iimura discussed Robert Whitman’s Two Holes of Water, No. 2 in his article “Special Report! Seismic Rumbles from the Underground” (1966, pp. 89–98) and again in the same journal, with a photographic insert: “Chitei ni Inanake Nandaguraundo,” Eiga Hyoron, 24 (May 1967): p. 69.

Punching Holes into the Filmstrip

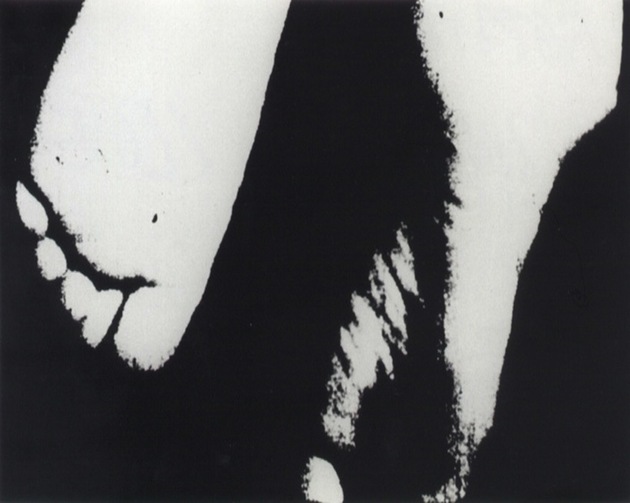

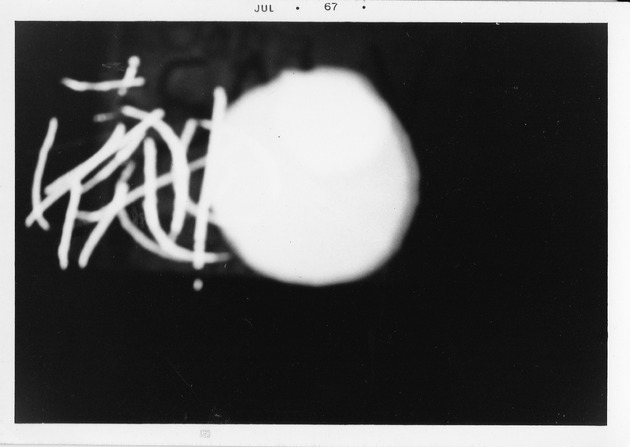

At the Expanded Art Festival, held at the Kishi Gymnasium in Shibuya on March 21 and 22, 1970, Iimura once again projected onto inflated objects for his performance Floating (Fig. 14–16).9Organized by dance critic Ichikawa Miyabi, the Expanded Art Festival was primarily a dance event with performances by Atsugi Bonjin, Kuni Chiya, and Ankoku Butoh dancer Hijikata Tatsumi’s disciple Ishii Mitsutaka. Ichikawa Miyabi wrote extensively on intermedia in the pages of SD (Space Design) and anticipated for it to instigate new directions in dance. He was based in New York when Iimura arrived in 1966 and let Iimura stay in his flat apartment while searching for a place to live. Reeling black film leader filmstrips into three 16mm projectors aimed at large black balloons made by sculptor Onishi Seiji, Iimura used a hole puncher to perforate the filmstrip. Light passing through the holes created circular flashes while the recorded sounds of speeches by Black Panther Party members played as the soundtrack (Fig. 17). The white flashes gradually increased until the voids created by the circular holes eventually caused the filmstrip to snap. In the absence of prerecorded footage, the act of film projection is reduced to its most bare-bones, purely mechanical form, revealing the common denominators of light and shadow. As such, the technical apparatus of cinema in this performance highlights its own existence, foregrounding the usually hidden mechanics of projection.

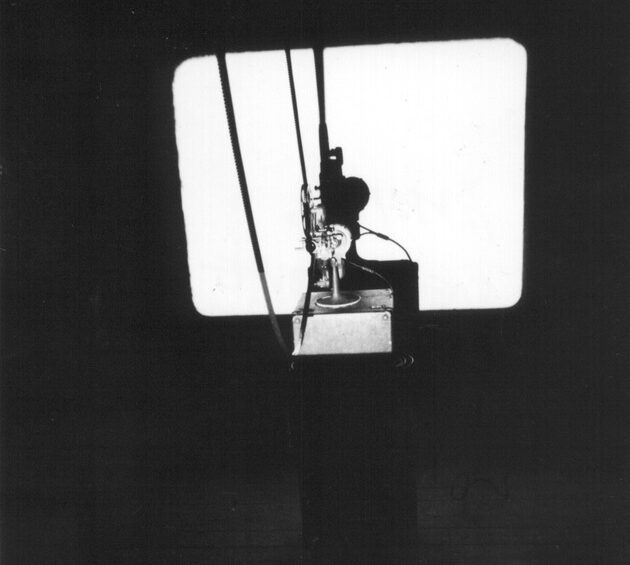

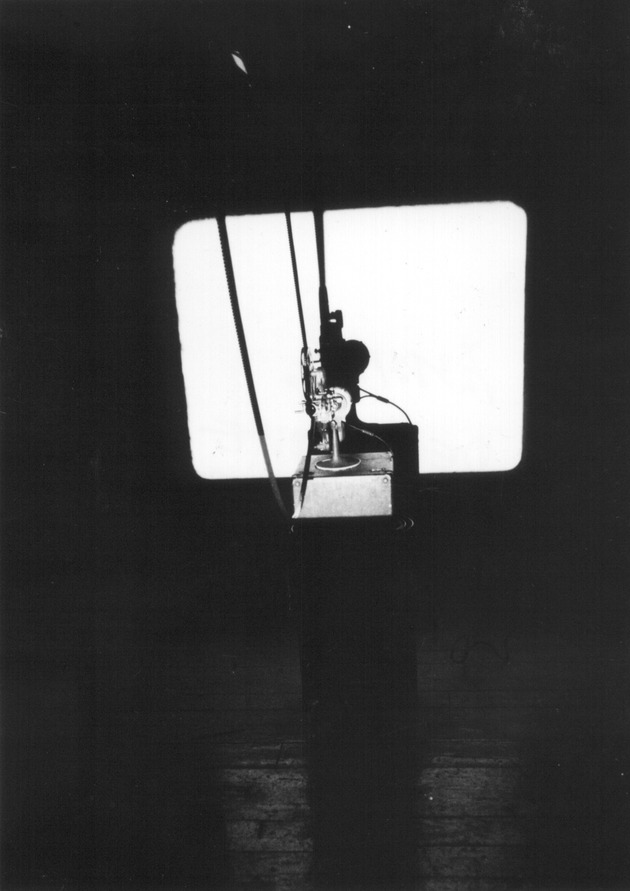

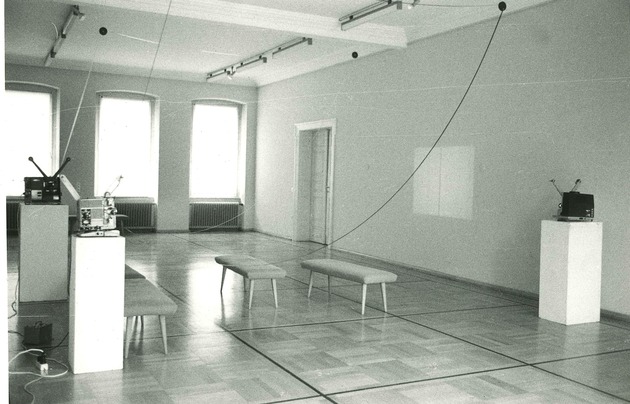

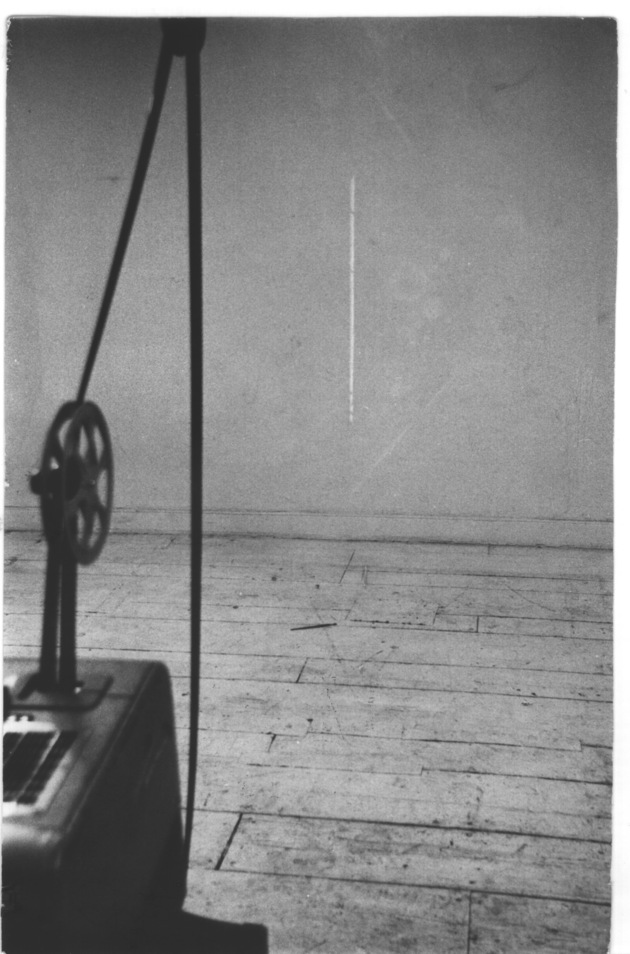

Iimura began to hole punch performatively in his first film installation, Dead Movie, 1964, in which two 16mm projectors, one with a black film leader hung and looped from the ceiling and another operating with no film, were placed against opposite walls and facing each other (Fig. 18).10Dead Movie was presented at Tokyo’s Goethe-Institut (1964), Judson Gallery, New York (1968), and Nichidoku Gendai Ongaku Enso-kai, Tokyo, in 1970. When Iimura added a third projector to the installation at Judson Gallery, he named it Projection Piece (1968–72). For more information on Dead Movie, see Iimura’s article “Media Ato to shiteno Eizo: Jisaku ni Kakwaru Noto,” (The Image as Media Art: Notes on My Own Work) in Shinsuke Ina (ed.), Media Ato no Sekai: Jikken Eizo 1960–2007 (Tokyo: Kokusho Kankokai, 2008), p. 29–44. The hole punch, a destruction of material for the creation of light, was what Iimura called a “peep window” that invites our eyes through the film and onto the screen, or in the case of this installation, onto the projector positioned on the other side. He continued using the technique in works such as Circle & Square (1981), most recently performed in July 2013.

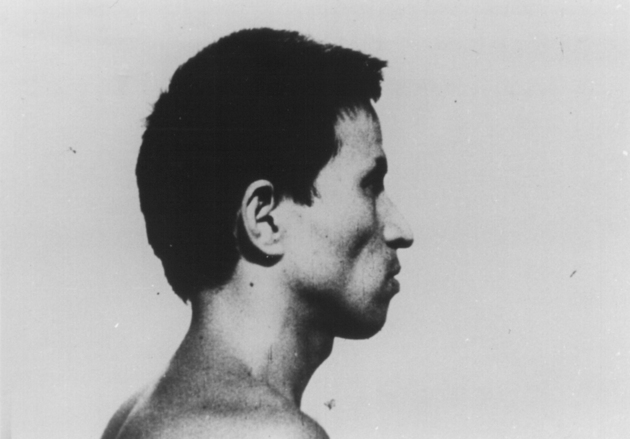

By 1970, the hole unch had become a recurring motif in Iimura’s films and presentations. In an essay on his film Onan (1963), Iimura outlined the work’s multiple versions (he re-edited the piece for each screening). Unusually for Iimura, this film has a narrative, and it concerns a young man overwhelmed with adolescent lust (Fig. 19). In the film’s fifth presentation, Iimura pierced the filmstrip with holes that bore no relationship to the images presented.11There was, however, one exception: at one point, the main character burns holes in the nudes in his erotic magazines in an attempt to efface his lechery. In Shikan ni Tsuite (On Eye Rape, 1962), Iimura and Nakanishi Natsuyuki, member of Hi Red Center, had commented on the absurdity of censorship by punching holes and scratching onto a sex-education film Nakanishi found in a dustbin (Fig. 20). The perforations in On Eye Rape parody attempts to censor sexuality by the Japanese establishment with the blocking of the image by virtue of penetrating through film material. Although sexuality remained a key theme in his practice, Iimura’s concern shifted towards showing his audience the workings of the film apparatus as a reason for punching holes into his own work (Fig. 21–22). In his essay reflecting on Onan, he describes the act of hole punching as “less a destruction than a spotlight on the illusory nature of the image.”12Iimura, Takahiko, “Eiga no Jikken ka Jikken no Eiga ka: Onan no Ba’ai” (A Film Experiment or Experimental Film?: The Case of Onan) Eizo Geijutsu, 3 (February 1965): p. 20. The sudden appearance and disappearance of a white circle of light encourages an awareness of the materiality of the filmstrip and the discrete nature of each frame. For Iimura, “Film is material first and only subsequently an image.”13Iimura, Takahiko, “Community of Images,” p. 156.

Introduction to Intermedia

By the time Iimura moved to New York in 1966, he had been experimenting with expanded modes of projection for several years.14In 1966 Iimura received a fellowship to attend an international summer seminar at Harvard University and a visiting artist fellowship from the Japan Society, New York. He was deeply inspired by New York’s underground film scene and the emerging artistic discourses of intermedia and expanded cinema, which he felt were closely related to his practice. That December, he reported what he had encountered in the United States in the journal Eiga Hyoron (Film Criticism), in what was to be the first text to introduce intermedia to Japan. In the article, he discussed recent works by Stan VanDerBeek, Robert Whitman, and the media art collective USCO that he had seen at the New York Film Festival and that represented what he understood to be the new wave of American independent film. Earlier that same year, Dick Higgins had highlighted the space between distinct media as a neglected field and pointed to its exploration as a potential source of stimulation in the arts.15Dick Higgins, “Intermedia”, Something Else Press Newsletter, 1, 1 (February 1966): p. 1–3. Channeling aspects of Higgins’s interpretation, Iimura described intermedia as “the expansion, combination, or dare I say the copulation of media.”16Iimura Takahiko, “Tokuho! Meidou Tsuzuku Anda guraundo” (Special Report! Seismic Rumbles from the Underground), Eiga Hyoron, 23 (December 1966): p. 22. Although their descriptions share many characteristics, Iimura departs from Higgins’s theory in one crucial way. Whereas Higgins resists attaching the concept of intermedia to any artistic movement or genre,17Higgins drew inspiration from Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s use of the word “intermedium” and included in his concept of intermedia artworks ranging from pattern poetry to Happenings. See Higgins, “The Origin of Happening,” American Speech, 51, 3/4 (Autumn–Winter 1976): p. 271. Iimura regards it as synonymous with what is known as “expanded cinema”18Iimura Takahiko, “Special Report! Seismic Rumbles from the Underground,” p. 22. —in other words, he sees it as intrinsically linked to cinema and the film medium. Iimura’s essay, along with his own works, had a significant influence on the way intermedia was to be received in Japan, as seen in the preponderance of underground filmmakers represented in the lineup for Runami Gallery’s Intermedia event on May 23–28, 1967, and the abundance of slide and moving-image projection in the events that were later billed in Japan as intermedia.19The underground filmmakers who participated in Runami Gallery’s “Intermedia” event include Donald Richie, Nagano Chiaki, Okabe Michio, Obayashi Nobuhiko, Takabayashi Yoichi, Adachi Masao, Jonouchi Motoharu, Miyai Rikuro, Noda Shinkichi, and Kanesaka Kenji. Iimura was listed in the pamphlet but was not able to participate. U.S.-based artists on the program included Stan Brakhage and Aldo Tambellini.

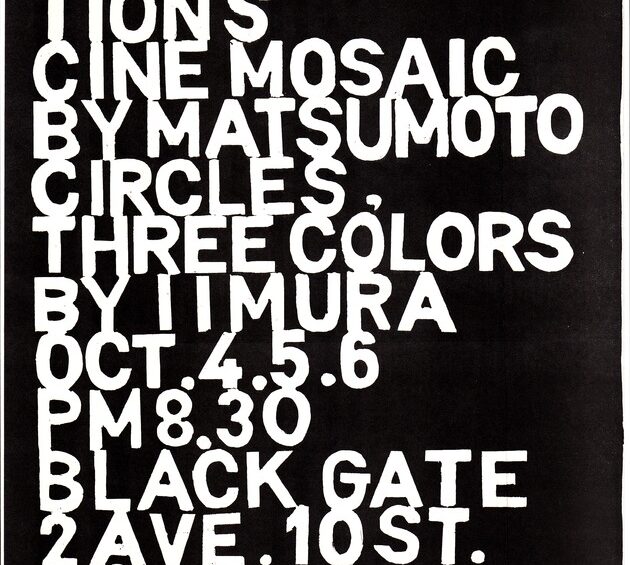

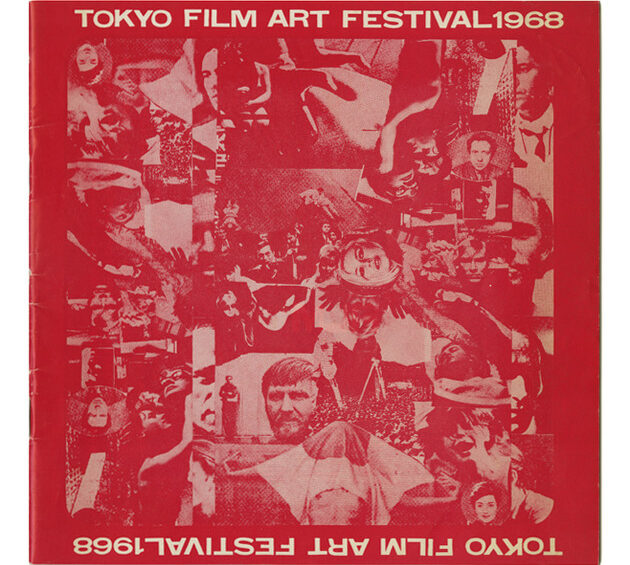

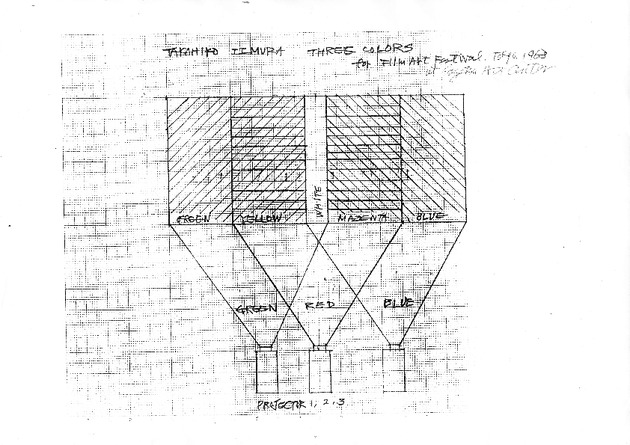

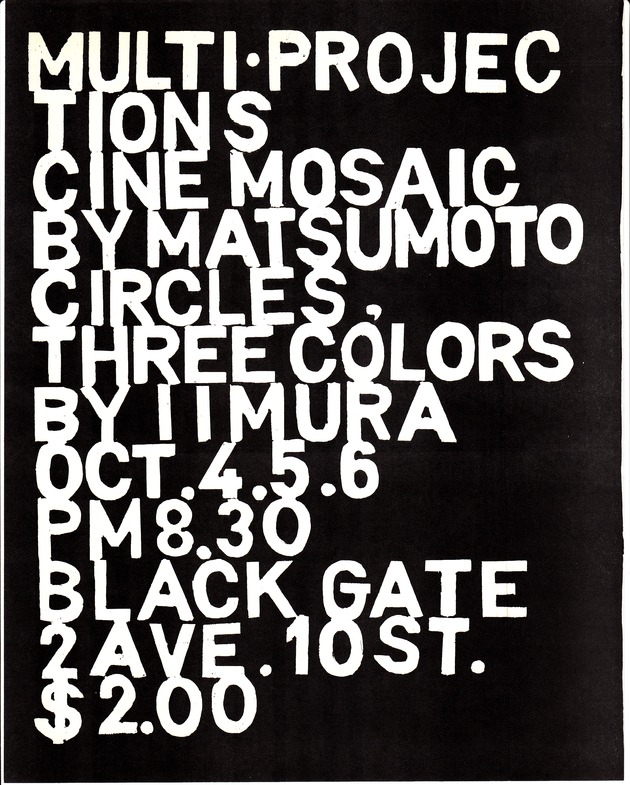

In the United States, Iimura was stimulated to discover multiple projectors used in art that he regarded as intermedia. Multiple projection, which Iimura saw as “an escape from the impasse of linear approaches to projection and something that demands an active engagement from the audience,”20Iimura, Takahiko, “Community of Images,” p. 154 was a technique that he employed in his own presentations. In Lilliput Okoku Butokai No. 2 (Dance Party in the Kingdom of Lilliput No. 2, 1966), Iimura projected two versions of the original Dance Party in the Kingdom of Lilliput (1964) onto two screens placed side by side (Fig. 23).21A Dance Party in the Kingdom of Lilliput follows Kazakura Sho performing outdoors in various spaces. The title is a reference to a poem by Henri Michaux and was used by Kazakura in performances, starting with his performance for the event Sweet 16. One of the projections showed a re-edited version, with scenes randomly rearranged, removed, or scratched. The presentation, which Iimura equated to concrete poetry owing to the focus on layout over content, allowed for the two projections to interact with one another, to forge unexpected relationships between the images.22Iimura Takahiko, “Shi to Eiga” (Poetry and Cinema) in Eizo Jikken no tame ni: Tekisuto, Conseputo, Pafomansu (For Experiments in the Image: Text, Concept, Performance) (Tokyo: Seido-sha, 1986), p. 17. Originally published in Pietoro, August 1970. Three Colors, presented in 1968 at the Black Gate in New York and at the Tokyo Film Art Festival at the Sogetsu Art Center, was a triple projection piece with uninterrupted gleams of blue and green projected alongside each other and red overlapping both in the middle (Fig. 24–27).23Presented together with Miyai Rikuro’s Sekibun Genshogaku (Integral Phenomenology, 1968) and Michael Snow’s Wavelength, Iimura’s triple projection Three Colors marks a shift in experimental film towards an engagement with what was later to be named structural cinema. The screening was presented at the symposium “What Does Cinema Mean to Me?” October 24, 1968. Recalling experiments in synesthesia carried out by the early Futurists, Iimura’s multiple projections mixed primary colors to create a white stream between the overlapping hues.24In “Abstract Film – Chromatic Music” (1912), Bruno Corra, one of the authors of the Futurist film manifesto (1916), wrote of his experiments, conducted with his brother Arnolda Ginna, in creating musical octaves using color projection. Iimura froze the frame and changed projection speeds to shift the color gradations in what he considered a performance of no fixed duration.

Intermedia not only affected Iimura’s art but took the entire Japanese art scene by storm in the late 1960s. After events such as the Intermedia Art Festival in January 1969 and Cross Talk Intermedia in February 1969, intermedia was subsumed into the rhetoric of the World Exposition in Osaka that was to be held in 1970. Iimura’s contempt for the event, which he described as “an amusement park,” stemmed largely from its use of multiple projection.25Iimura Takahiko, “Bankokuhaku no Eizo Hyogen” (Film Expression at the Osaka Expo), SD (Space Design), 70 (August 1970): p. 42–45. Iimura declared that due to the commercial framework of the installations, the artists commissioned to create the spaces were employing multiple projection in a formulaic way. For Iimura, intermedia designated practices that went beyond established ways of working with a medium, in particular the film medium and its presentation.

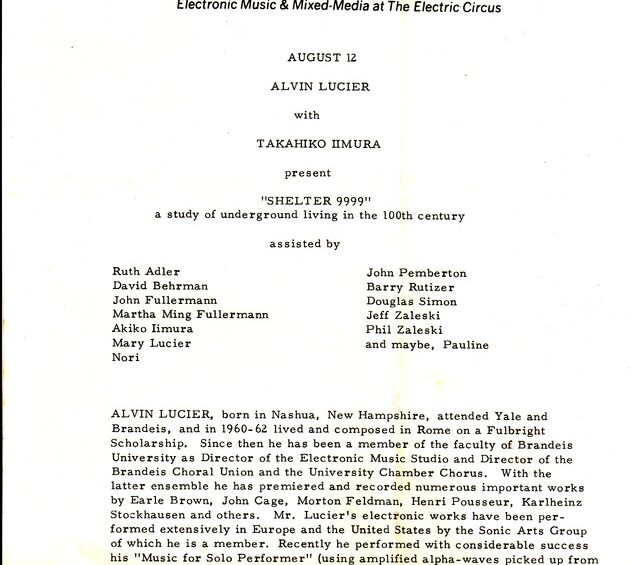

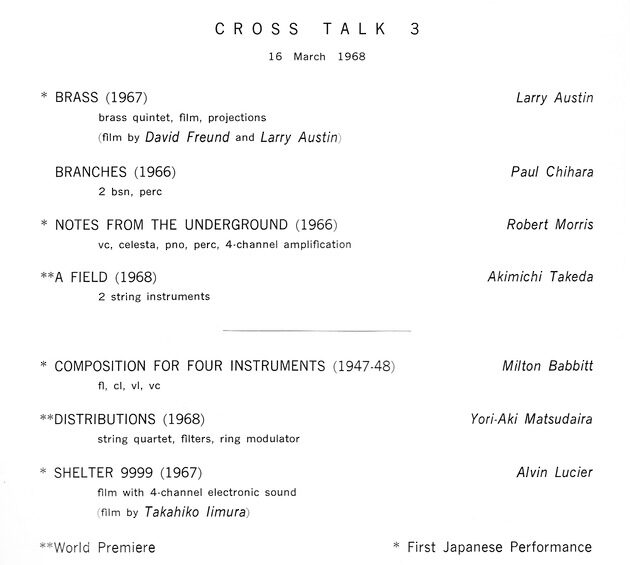

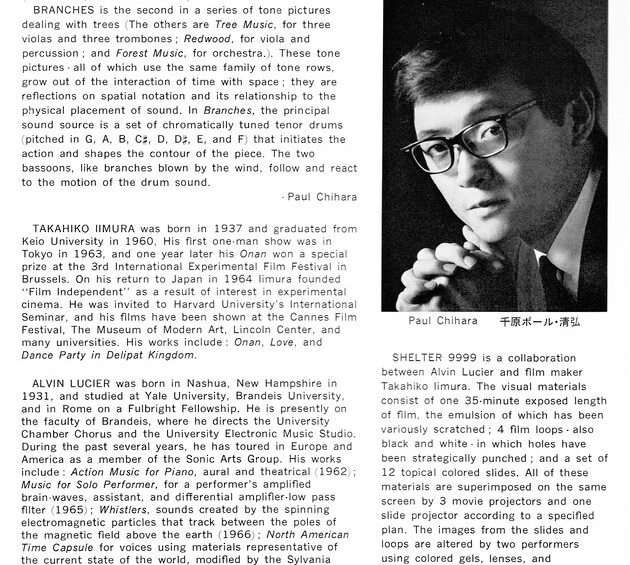

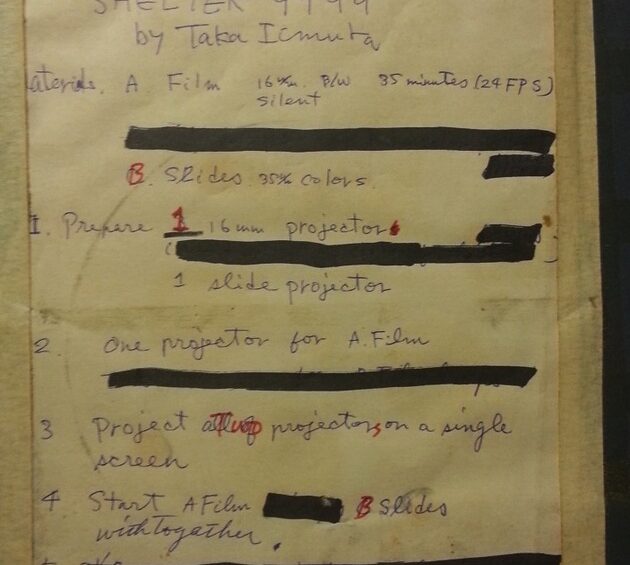

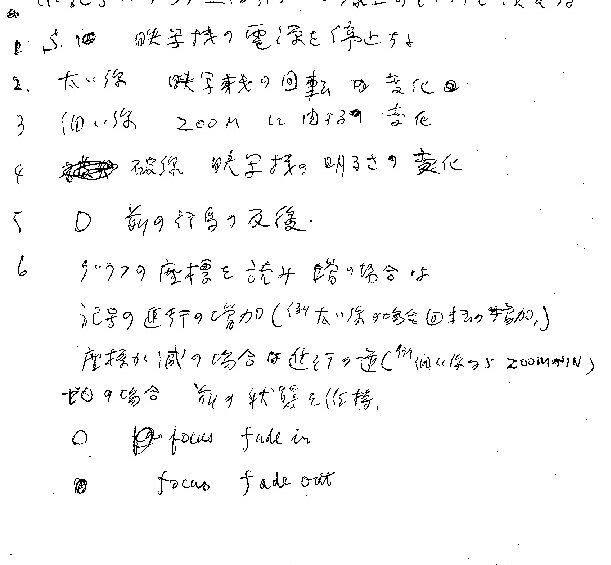

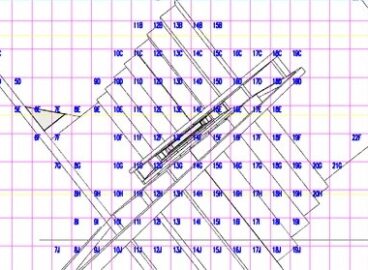

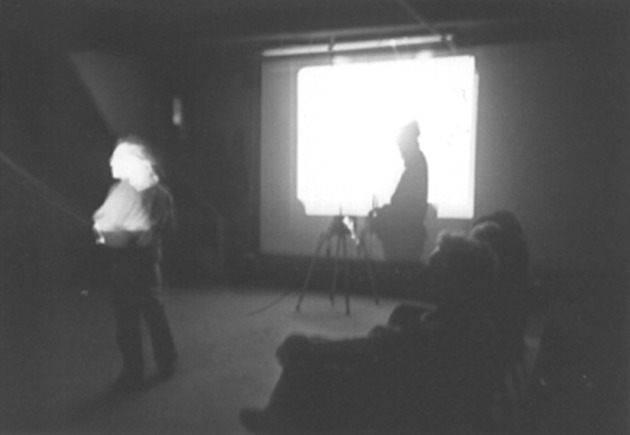

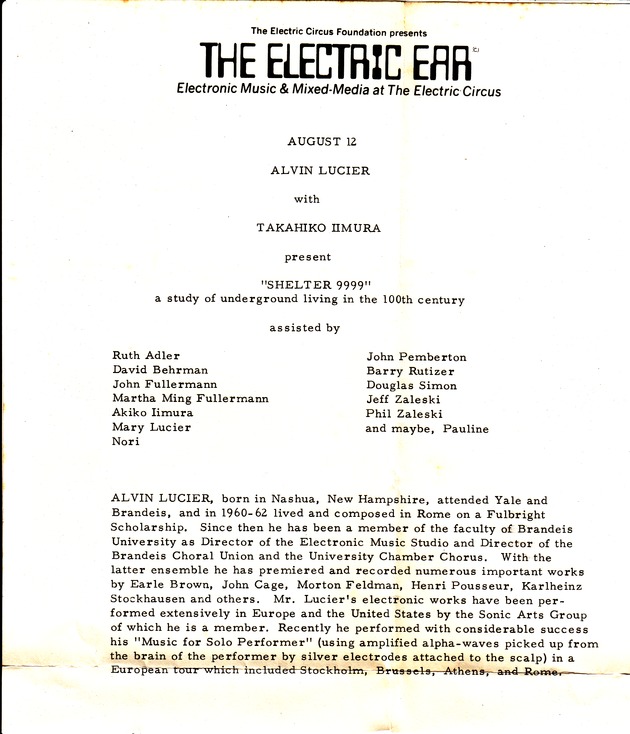

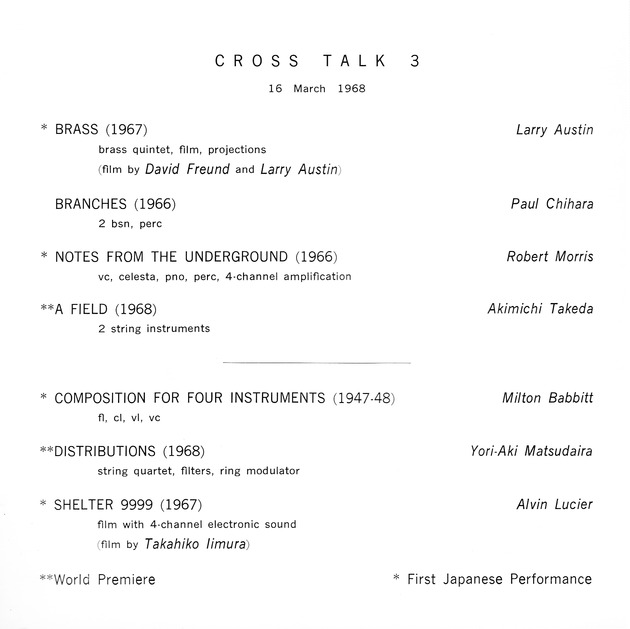

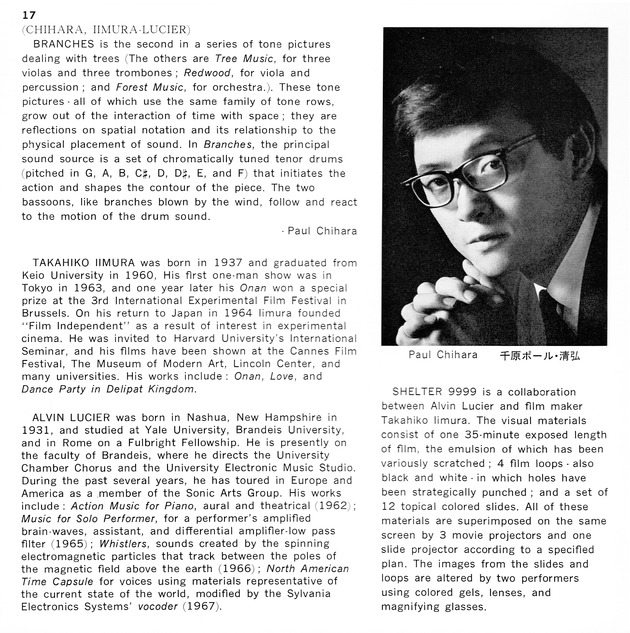

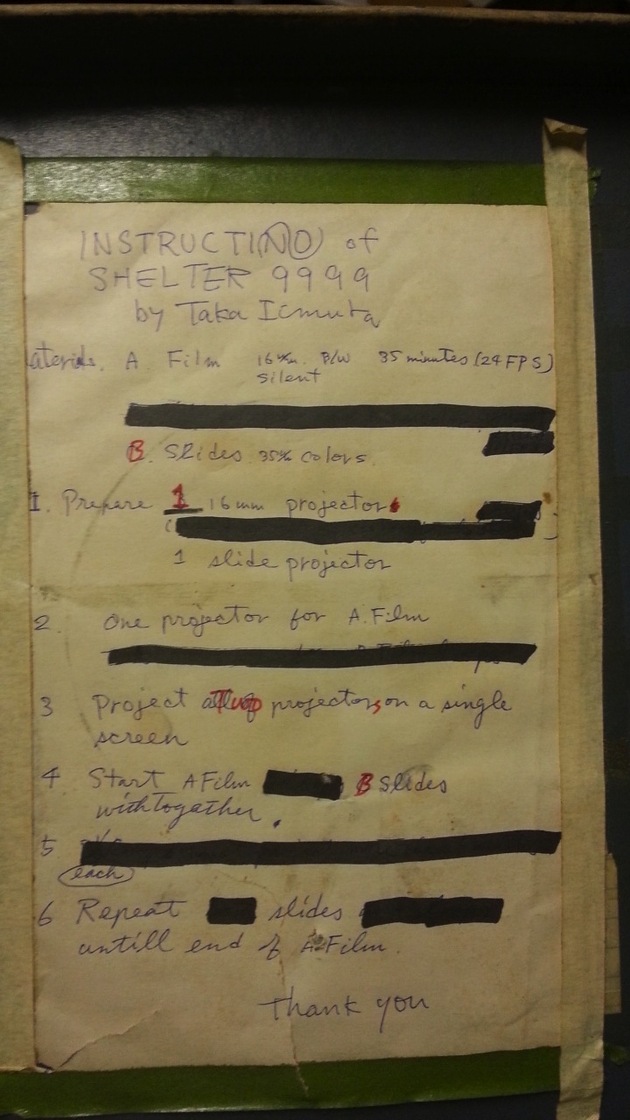

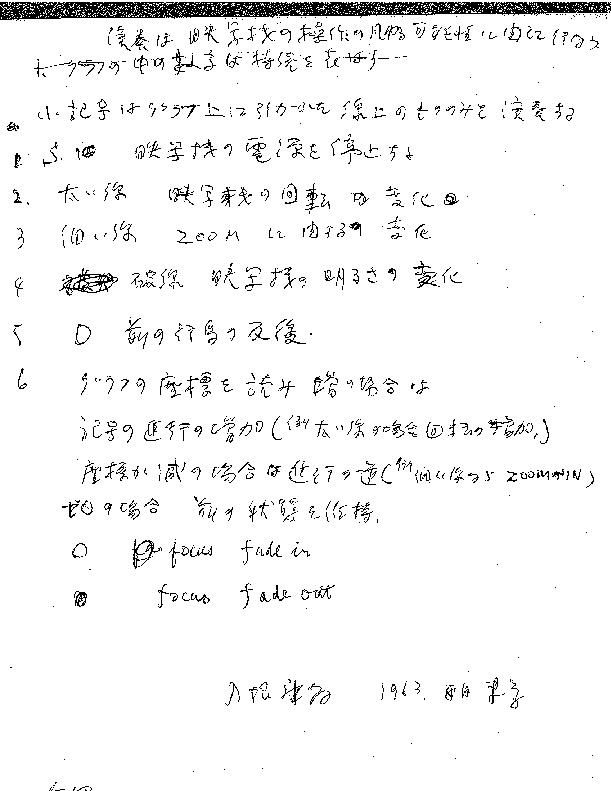

Describing the pavilions at the Osaka Expo as closed spaces that placed audiences in pre-arranged frameworks,26Iimura, Takahiko, “Bankokuhaku no Eizo Hyogen,” p. 43. Iimura sought to create open environments through the use of multiple projection. In an event at the Black Gate, Matsumoto Toshio was asked to operate one of the three projectors used in Iimura’s Circles and was given free reign to decide which of fifty or sixty loop-films to project, when to change reels, and where to project the images (Fig. 28).27Matsumoto Toshio presented Tsuburekakatta Migime no Tameni (For My Damaged Right Eye) with Iimura Takahiko’s Circles and Three Colors at the Black Gate Theater, October 4 to 6, 1968. In a 1967–68 collaboration with Alvin Lucier, whom Iimura had met in Boston in 1966, Iimura presented Shelter 9999, an improvised performance of film and slide projections to tape music by Lucier. Billed in promotional material as “the study of the underground world,” Shelter 9999 was showcased in auditoriums, gymnasiums, and nightclubs: the Filmmakers’ Cinematheque, Black Gate, Page Hall, and the Electric Circus in New York; Gray Hall in Hartford, Connecticut; a church on the outskirts of Chicago; and in Tokyo as part of Cross Talk 3. For the Electric Circus performance, Iimura covered the walls and parts of the ceiling with slide and moving-image projections of newspaper clippings that were gradually replaced with white flashes to conclude the show (Fig. 29). At Cross Talk 3 in Tokyo, he pointed all the projectors toward one screen on which the images overlapped, disappeared into, and reappeared out of one another as he swapped lenses and used different color filters (Fig. 30–31). In his essay “Community of Images,” Iimura wrote that he had used as many as seven projectors and described a version employing two film projectors reeling scratched and hole-punched black film leader and two slide projectors showing photographs he had taken of banners, neon signs, and graffiti (Fig. 32). The instructions, recently discovered along with a print of the film used as the central projection, are heavily marked up with alterations for individual performances (Fig. 33). Iimura’s multi-projection events were thus reshaped on each occasion for the spatial context in which they were presented.

Collaborations: Music, Dance, and Theater

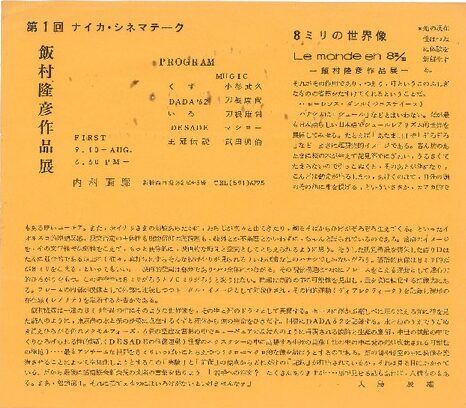

Iimura’s collaborations with musicians and dancers resulted in works that were closer than his multi-projection performances to Higgins’s original notion of intermedia. At a screening at the Naiqua Gallery (August 8 and 9, 1963), Dada ’62 (1962), a filmed record of the 15th Yomiuri Independents exhibition,28The Yomiuri Independent Exhibition was a series of exhibition organized by the Yomiuri newspaper, held at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum between 1946 and 1963. For more on the exhibition, see Tomii, Reiko, “Yomiuri Independent Exhibition,” in Doryun Chong et. al (eds.), From Postwar to Postmodern: Art in Japan 1945–1989 (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2012), p. 116–117. was projected according to Iimura’s interpretation of a graphic score that Tone Yasunao had composed for the occasion (Fig. 34–36). Using an 8mm projector, Iimura blurred the focus, adjusted the projection speed, froze frames, and moved the projection over the walls as he followed Tone’s score. The audience, seated on the floor of the gallery, was made to shift positions for each film during the event as Iimura projected onto different walls of the gallery. At a dance recital arranged by Kuni Chiya that same year, Iimura chased small screens held up by dancers with his projection of Sakasama (Upside Down, 1963), a film largely consisting of footage of women’s legs captured upside-down at a department store (Fig. 37). The images, vertically juxtaposed with the bodies of all-female dance troupe, mirrored the latter, connecting the real with the recorded.29Iimura, Takahiko, “Involuvumento – Aruiwa Jiden” (Involvement – In Account of One’s Life) in Bijutsu Techo, 327 (May 1970): p. 179.

Such encounters and collaborations with dancers and performance artists encouraged Iimura to treat the act of recording as a performance in and of itself. Iimura was invited to join Ankoku Butoh dancers in a 1963 recital at Asahi Hall and to participate in their performance in the role of an observer. Iimura attempted to translate the dancers’ gestures into camera movements, treating “[his] hand as an extension of the camera, or the camera as an extension of [his] hand.”30Julian Ross, “As I See You You See Me,” in Vertigo Magazine, 31, 2012. Originally published in 2010 in Midnight Eye. The result, shot on an 8mm spring-wind-motor camera to allow for maximum mobility, has been described as an anti-document, due to its lack of clarity.31Stephen Barber, Hijikata: Revolt of the Body (Washington, DC: Solar Books, 2010), p. 54. At the same event, the butoh dancers invited still photographers to join them onstage as observers. Performer Kazakura Sho took a seat on a plinth propped fifteen feet above the audience and gazed at them as well as the performance, turning the spectators into subjects of observation.32Bruce Baird, Hijikata Tatsumi and Butoh: Dancing in a Pool of Gray Grits (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), p. 92–94. The event demonstrated the interlacing of art forms that were of central concern to the art community during that period and revealed Iimura’s avid questioning of conventional roles assigned to any given art form. Moreover, Iimura’s action posed a challenge to the notion that performance exists only in the present: his ‘performance’ as an observer of the dance endures in the camera movements of his film.

The Medium in Intermedia

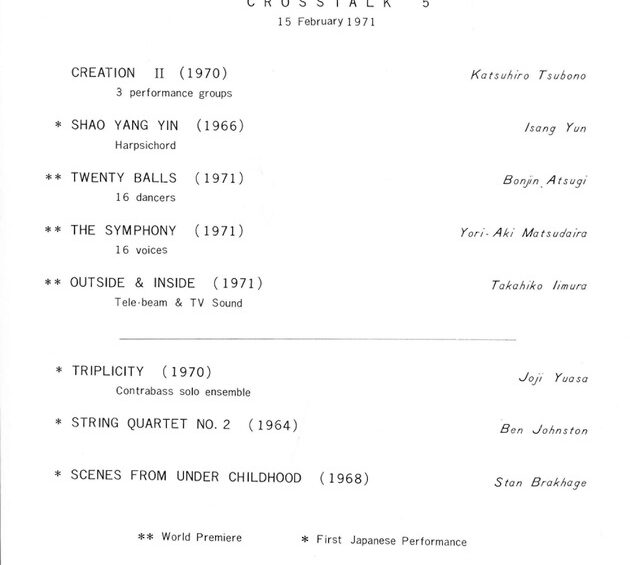

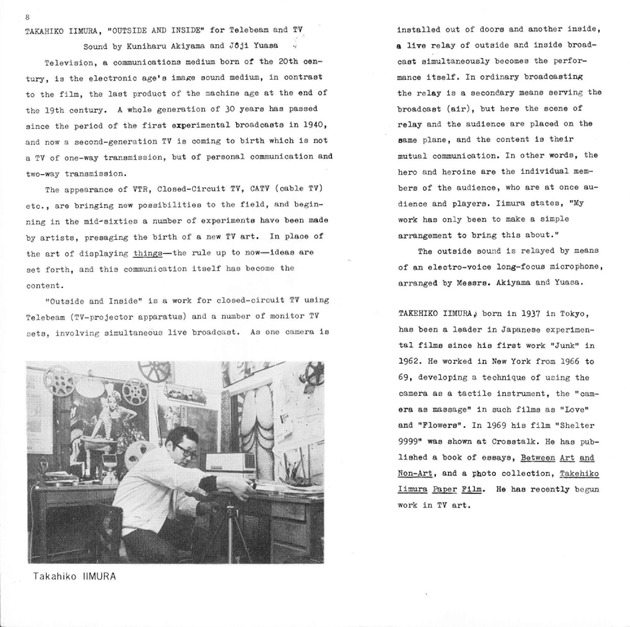

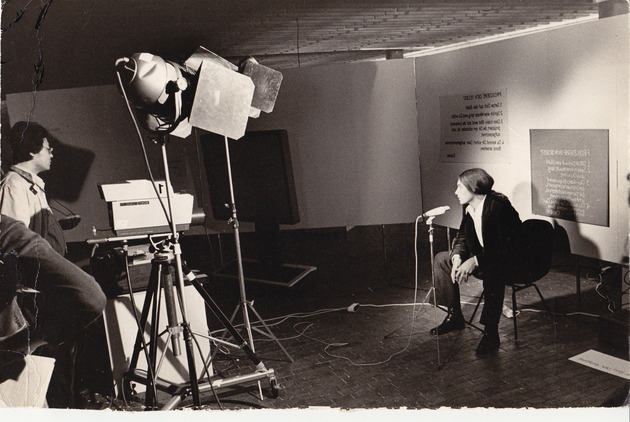

In the early 1970s, Iimura started to experiment with video performances. In Outside and Inside, presented as part of the crossdisciplinary festival Cross Talk 5, he used the closed circuit and live relay system of Telebeam (TV-projector apparatus) to transmit interviews conducted with people walking from the street into the auditorium (Fig. 38–40). In Project Yourself (1973), he employed the possibility afforded by television and video to record and project simultaneously by giving audience members an opportunity to speak or act freely for one minute in front of the camera while their image was projected on a screen behind them (Fig. 41). This medium-specific use of video is consistent with Iimura’s use of film in his film performances (Fig. 42–43). Starting with Dead Movie, he made the filmstrip the principal point of focus of his film installations, moving it, together with the projection apparatus, out of the projection room and into the exhibition space.

Iimura’s view of screenings as occasions for performance developed new directions for film exhibition in the Japanese art scene. His removal of the projector from the movie theater and into gallery spaces opened up new perspectives that shifted film projection off the screen and onto widely divergent surfaces. While Iimura pushed the limits of the film medium in his performances and collaborations with other artists, his performances revealed an unyielding commitment to film. Despite their close association with other forms of expression, Iimura’s films deal with the specificities of film: its materiality, technology, and the conventions of its presentation.33I expand on this notion in my analysis of Iimura’s recent re-performances of White Calligraphy (1965) in Ross, Julian (2013), “Projection as Performance: Intermediality in Japan’s Expanded Cinema,” in Lúcia Nagib and Anne Jerslev (eds.), Impure Cinema: Intermedial and Intercultural Approaches to Cinema (London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2013), p. 249–267. A diagram that instructs a performative version of White Calligraphy can be found in Iimura Takahiko, Geijutsu to Hi-geijutsu no Aida (Tokyo: San’ichi Shobo, 1970), p. 264. In his conception of intermedia, Iimura saw the expansion of cinema as resulting from its interactions with other mediums: “By reducing each medium to its bare essence,” he wrote, “intermedia, actually reveals the independence of a medium.”34Iimura, Takahiko, “Community of Images”, p. 157. His film performances highlight the fundamental components of cinema—screen, filmstrip, and projector—by displacing them from their prescribed frameworks. Thus he exposes the rigidity of conventional film projection. In the same way that the round, punched holes admit light through the square frame of the filmstrip and onto the screen, Iimura’s film performances of the 1960s spotlight the limits and specificities of the medium.

- 1Oshima Tatsuo refers to Iimura’s screening at Sasori-za (Theatre Scorpio), where he repeatedly referred to his own presentations as “film actions” in the Q&A session on February 20,1970, as part of the Iimura Takahiko: Cinema Love-In program. (Oshima, Tatsuo. “Eizo no Umareru Chitai: Iimura Takahiko to Arakawa Shusaku no Eiga Sakuhin o Mite,” SD (Space Design), 72 [October 1970]: 104.)

- 2Iimura Takahiko, “Imeji no Comyuniti” (Community of Images), Kikan Firumu 2, (February 1969): p. 153.

- 3Hi Red Center was a performance group active from 1963 to ’64. Members included Takamatsu Jiro, Akasegawa Genpei, and Nakanishi Natsuyuki, as well as occasional guests. They often performed in public spaces but also exhibited in art galleries such as the Naiqua Gallery, where Iimura Takahiko’s works were screened. Hi Red Center’s members later became associated with Fluxus.

- 4Akasegawa Genpei, however, claims that he cut Takamatsu Jiro’s jacket in the shape of the projected image. See Akasegawa, Genpei, Tokyo Mikisa Keikaku: Hi Red Center Chokusetsu Kodo no Kiroku (Tokyo Mixer Plan: Records of Hi Red Center’s Direct Actions) (Tokyo: Chikuma, 1994), p. 353.

- 5Iimura Takahiko (1969). “Tatsuki Yoshihiro Shashi-ten nado: Hadaka ni tsuite (Tatsuki Yoshihiro’s Photography Exhibition: On Naked Bodies),” SD (Space Design), 65 (March): p. 109.

- 6After relocating to New York in 1966, Iimura participated in the 5th Avant-Garde Festival (1967), where he projected his films onto the face of Charlotte Moorman and other artists while they performed, attesting to his desire to forge new relationships and attain unexpected results with his films. See Iimura Takahiko, “Involuvumento – Aruiwa Jiden” (Involvement – In Account of One’s Life) in Bijutsu Techo, 327 (May 1970): p. 179. Projections onto the body became familiar offerings on Tokyo’s art scene in performances that included Jonouchi Motoharu’s Gewaltopia at Runami Gallery (1967), Yamaguchi Katsuhiro’s Lulu (1967), Tachimi Tadahiro’s Psychedelic Show (1968) at Modern Art in Shinjuku, in a pink film Buru Firumu no Onna (Blue Film Woman, Mukai Kan, 1969), and in films produced and/or distributed by the Art Theater Guild: Hatsukoi: Jigoku-hen (Inferno of First Love, Hani Susumu, 1969), Erosu purasu Gyakusatsu (Eros Plus Massacre, Yoshida Kiju, 1969), Tokyo Senso Sengo Hiwa, (The Man Who Put His Will on Film, Oshima Nagisa, 1970).

- 7Cross Talk Intermedia was the fourth event of the Cross Talk series organized by the American Cultural Center to foster collaboration between Japanese and American artists working primarily in the field of music. Spearheaded by Roger Reynolds and Kuniharu Akiyama, the event was unique in the series for its focus on expanded cinema. Participants included Stan VanDerBeek, Alvin Lucier, Robert Ashley, George Cacioppo, Salvatore Martirano, Gordon Mumma, Ronald Nameth, David Rosenboom, Ichiyanagi Toshi, Matsumoto Toshio, Yuasa Joji, Takemitsu Toru, Kosugi Takehisa and Shiomi Mieko. Iimura’s Circles was performed on February 6, 1969, using the same balloons made by Shinohara Ushio for Matsumoto Toshio’s Projection for Icon.

- 8The use of balloons had been gaining popularity among Japanese artists such as Kazakura Sho, Isobe Yukihisa, and Onishi Seiji, who found in the spherical objects an alternative to the fixed position imposed by the frame conventionally found in exhibitions. Kazakura, at the “Intermedia” event at Runami Gallery, May 23 to 28, 1967, threw balloons into the gallery space during one of the screenings as a performative interruption, marking the first encounter between film projection and balloons in Japan, Other than Kazakura’s, Matsumoto’s and Iimura’s works that have already been mentioned, Azuchi Shuzo Gulliver and Yoshizawa Toshimi with Ishii Kahoru also took part in events that involved projections onto balloons. Balloons had also become a common feature internationally in performative situations such as Robert Whitman’s Two Holes of Water, No. 2 (1966), which Iimura reviewed in an article for Eiga Hyoron. Iimura discussed Robert Whitman’s Two Holes of Water, No. 2 in his article “Special Report! Seismic Rumbles from the Underground” (1966, pp. 89–98) and again in the same journal, with a photographic insert: “Chitei ni Inanake Nandaguraundo,” Eiga Hyoron, 24 (May 1967): p. 69.

- 9Organized by dance critic Ichikawa Miyabi, the Expanded Art Festival was primarily a dance event with performances by Atsugi Bonjin, Kuni Chiya, and Ankoku Butoh dancer Hijikata Tatsumi’s disciple Ishii Mitsutaka. Ichikawa Miyabi wrote extensively on intermedia in the pages of SD (Space Design) and anticipated for it to instigate new directions in dance. He was based in New York when Iimura arrived in 1966 and let Iimura stay in his flat apartment while searching for a place to live.

- 10Dead Movie was presented at Tokyo’s Goethe-Institut (1964), Judson Gallery, New York (1968), and Nichidoku Gendai Ongaku Enso-kai, Tokyo, in 1970. When Iimura added a third projector to the installation at Judson Gallery, he named it Projection Piece (1968–72). For more information on Dead Movie, see Iimura’s article “Media Ato to shiteno Eizo: Jisaku ni Kakwaru Noto,” (The Image as Media Art: Notes on My Own Work) in Shinsuke Ina (ed.), Media Ato no Sekai: Jikken Eizo 1960–2007 (Tokyo: Kokusho Kankokai, 2008), p. 29–44.

- 11There was, however, one exception: at one point, the main character burns holes in the nudes in his erotic magazines in an attempt to efface his lechery.

- 12Iimura, Takahiko, “Eiga no Jikken ka Jikken no Eiga ka: Onan no Ba’ai” (A Film Experiment or Experimental Film?: The Case of Onan) Eizo Geijutsu, 3 (February 1965): p. 20.

- 13Iimura, Takahiko, “Community of Images,” p. 156.

- 14In 1966 Iimura received a fellowship to attend an international summer seminar at Harvard University and a visiting artist fellowship from the Japan Society, New York.

- 15Dick Higgins, “Intermedia”, Something Else Press Newsletter, 1, 1 (February 1966): p. 1–3.

- 16Iimura Takahiko, “Tokuho! Meidou Tsuzuku Anda guraundo” (Special Report! Seismic Rumbles from the Underground), Eiga Hyoron, 23 (December 1966): p. 22.

- 17Higgins drew inspiration from Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s use of the word “intermedium” and included in his concept of intermedia artworks ranging from pattern poetry to Happenings. See Higgins, “The Origin of Happening,” American Speech, 51, 3/4 (Autumn–Winter 1976): p. 271.

- 18Iimura Takahiko, “Special Report! Seismic Rumbles from the Underground,” p. 22.

- 19The underground filmmakers who participated in Runami Gallery’s “Intermedia” event include Donald Richie, Nagano Chiaki, Okabe Michio, Obayashi Nobuhiko, Takabayashi Yoichi, Adachi Masao, Jonouchi Motoharu, Miyai Rikuro, Noda Shinkichi, and Kanesaka Kenji. Iimura was listed in the pamphlet but was not able to participate. U.S.-based artists on the program included Stan Brakhage and Aldo Tambellini.

- 20Iimura, Takahiko, “Community of Images,” p. 154

- 21A Dance Party in the Kingdom of Lilliput follows Kazakura Sho performing outdoors in various spaces. The title is a reference to a poem by Henri Michaux and was used by Kazakura in performances, starting with his performance for the event Sweet 16.

- 22Iimura Takahiko, “Shi to Eiga” (Poetry and Cinema) in Eizo Jikken no tame ni: Tekisuto, Conseputo, Pafomansu (For Experiments in the Image: Text, Concept, Performance) (Tokyo: Seido-sha, 1986), p. 17. Originally published in Pietoro, August 1970.

- 23Presented together with Miyai Rikuro’s Sekibun Genshogaku (Integral Phenomenology, 1968) and Michael Snow’s Wavelength, Iimura’s triple projection Three Colors marks a shift in experimental film towards an engagement with what was later to be named structural cinema. The screening was presented at the symposium “What Does Cinema Mean to Me?” October 24, 1968.

- 24In “Abstract Film – Chromatic Music” (1912), Bruno Corra, one of the authors of the Futurist film manifesto (1916), wrote of his experiments, conducted with his brother Arnolda Ginna, in creating musical octaves using color projection.

- 25Iimura Takahiko, “Bankokuhaku no Eizo Hyogen” (Film Expression at the Osaka Expo), SD (Space Design), 70 (August 1970): p. 42–45.

- 26Iimura, Takahiko, “Bankokuhaku no Eizo Hyogen,” p. 43.

- 27Matsumoto Toshio presented Tsuburekakatta Migime no Tameni (For My Damaged Right Eye) with Iimura Takahiko’s Circles and Three Colors at the Black Gate Theater, October 4 to 6, 1968.

- 28The Yomiuri Independent Exhibition was a series of exhibition organized by the Yomiuri newspaper, held at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum between 1946 and 1963. For more on the exhibition, see Tomii, Reiko, “Yomiuri Independent Exhibition,” in Doryun Chong et. al (eds.), From Postwar to Postmodern: Art in Japan 1945–1989 (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2012), p. 116–117.

- 29Iimura, Takahiko, “Involuvumento – Aruiwa Jiden” (Involvement – In Account of One’s Life) in Bijutsu Techo, 327 (May 1970): p. 179.

- 30Julian Ross, “As I See You You See Me,” in Vertigo Magazine, 31, 2012. Originally published in 2010 in Midnight Eye.

- 31Stephen Barber, Hijikata: Revolt of the Body (Washington, DC: Solar Books, 2010), p. 54.

- 32Bruce Baird, Hijikata Tatsumi and Butoh: Dancing in a Pool of Gray Grits (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), p. 92–94.

- 33I expand on this notion in my analysis of Iimura’s recent re-performances of White Calligraphy (1965) in Ross, Julian (2013), “Projection as Performance: Intermediality in Japan’s Expanded Cinema,” in Lúcia Nagib and Anne Jerslev (eds.), Impure Cinema: Intermedial and Intercultural Approaches to Cinema (London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2013), p. 249–267. A diagram that instructs a performative version of White Calligraphy can be found in Iimura Takahiko, Geijutsu to Hi-geijutsu no Aida (Tokyo: San’ichi Shobo, 1970), p. 264.

- 34Iimura, Takahiko, “Community of Images”, p. 157.