In the middle of debris and ruin, the Seville Oranges (naranj) were shining from behind dusty leaves. And again it was pickaxes that would come down on the rooftops, and the mud brick and dirt that would fall.

—Ebrahim Golestan, From the Days Gone Narrate

The wind is blowing through the street, the beginning of ruination.

—Forough Farrokhzad, Let Us Believe in the Beginning of the Cold Season

Parviz Kimiavi’s 1973 film The Mongols is a collage of disparate images, sounds, and narrative components that come at the audience like a whirlwind. Produced by National Iranian Radio and Television, The Mongols revolves around various forms of “unearthing,” of old artifacts buried in the soil, of old medieval texts, of fragments of history (writing), of moving images from cinema technology, even its prehistory, and of the “new media” of the time, the television. There are two main characters in the film, a young filmmaker for the national television network (played by Kimiavi himself) and his wife (played by the late Fahimeh Rastkar), who is completing her doctoral research on the Mongol invasion of medieval Persia. As he avidly reads on film history and worries about his assignment to a remote and underdeveloped province, his world is invaded by phantasms of Mongol soldiers from the script of her unfinished dissertation. The “Mongols” of the film (who, as the opening scene reveals, are in fact nonactors recruited from ethnic Turkmens from the northeast of Iran), both spectral and documentary-like, make their first appearance in the present time at an excavation site, a ruin.

The Iranian New Wave, as that large and heterogeneous body of Iranian art films produced before the 1979 revolution came to be known, was besieged by ruins and ruination from the start. Retaining a faith in what Siegfried Kracauer (whose work at MoMA in the 1940s was a forerunner in thinking film history at a museum) saw as the cinema’s ability to redeem physical reality, this essay sets out to explore the cinematic renderings of the ruin and that of the body. 1For more on Kracauer’s engagement with MoMA’s Film Library, established in 1935, see David Culbert, “The Rockefeller Foundation, the Museum of Modern Art Film Library, and Siegfried Kracauer, 1941,” Historical Journal of Film, Radio, and Television 13, no. 4 (1993): 495–511. Other film historians and theorists who worked with the Film Library, before there was an academic discipline called “Film Studies,” include Jay Leyda, Paul Rotha, Fernand Léger, and Luis Buñuel. The New Wave still occupies an unsettled space, at once affectionately remembered and orphaned. On the one hand, in Iran, it has finally gained an honored place in film historiography, represented in books and articles published every year in Persian. On the other hand, many of the New Wave’s great films still cannot be shown in Iran, just as the academic film historiography, presumably global now, has yet to give it a chance to find its deserving place within the international canon of art (read modernist) cinema. Almost all of the examples presented here are drawn from MoMA’s upcoming film series Iranian Cinema before the Revolution, 1925–1979, a selection unparalleled in its scope and insight. In time, certain material formations come to the fore in this piece—the ruin, the anguished body, the museum display, the mud-brick wall, the old neighborhood passageway. 2For more extensive and in-depth variations of the analyses presented here, see Farbod Honarpisheh, “Fragmented Allegories of National Authenticity: Art and Politics of the Iranian New Wave Cinema of the 1960s and 1970s” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 2016).

Persepolis (Fereydoun Rahnema, 1960)

Fereydoun Rahnema’s 1960 essay film Persepolis is constructed as a lyrical portrayal of the most iconic archaeological site in contemporary Iran, the ceremonial capital of the Persian Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BCE). Persepolis is drenched in a sense of historical loss and grief. The destruction of the palace, which the voice-over declares was once a garden, is evoked through the imagery, music, and sound. The scale of ruin is expansive. Not naming the invading army responsible, adding so subtly yet another shade to the film’s overall ambiance of ambiguity, the tragedy of destruction is instilled into all of Iranian history, if not into all history.

The expansion of the temporality of destruction across the ages means opening the door to another form of allegorical arrangement, that of the slow destruction, the decay. Differentiated from abrupt “destruction by man,” the decay (in a built structure) is, for Georg Simmel, significant as it was brought about by the nonconscious, yet creative, forces of nature.3Georg Simmel, “The Ruin” (1911), in Essays on Sociology, Philosophy and Aesthetics, ed. Kurt H. Wolff (New York: Harper and Row, 1965), 260. Persepolis dwells on the gradual, still ongoing, destruction brought on by the elements. Nature is still advancing over the ruin, a reality emphasized not only by the voice-over narrative but also by the images of broken stone, stumps of pillars amid grass and flowers, shots of small animals wandering about the place, birds singing, sounds of wind and water.

The sight of antiquity here interrupts the continuity of the present time. Ruined structures, ancient or modern, it should be remembered, evoke other lives and worlds. Again, as Simmel saw it, the genuine ruin (ancient and decayed but not yet rendered unrecognizable in its fundamental formal features) creates “the present form of a past life,” and it does so in the fashion of “an immediately perceived presence.”4Simmel, “The Ruin,” 260. But in the place where Simmel looked for “balance,” “unity of form,” “metaphysical calm,” and the reconnections of nature and the spirit in the face of opposition and conflict, cinema is capable of opening radical fissures even as it brings together. And so in Persepolis the ruin of the past, set against a forceful and lively present time, emerges as a ghostly interruption.

The Hills of Marlik (Ebrahim Golestan, 1963)

This year,

last year,

thousands and thousands of years,

With the wind, the smell of pine’s oldness. . .

These words begin Golestan’s 1963 documentary The Hills of Marlik. Repeated again and again, these words mark the film as one concerned with temporality. The images preceding these words are of a pair of hands piecing together the broken parts of what seems to be an ancient artifact. A man sitting by a stream, the camera reveals. When this (re)assemblage is finished, a shot of a stylized clay pitcher placed by the water. “This year, last year, thousands and thousands of years . . .” We see a group of men, the archaeological excavation team of Marlik, with their small picks and brushes, unearthing the remains of a human skeleton. Suddenly, to the cue of a developing atonal music, a wipe cut radically changes the setting. The new scene is opened by a traveling camera moving through a dark space, passing by rows of objects suspended in the air. This twofold engagement with “archaeology” and the “museum display,” this fascination with excavation, with bringing old objects into the present time, shaped in the formative years of the New Wave, was to come back in its later years again and again.

The scenes built around displayed artifacts in The Hills of Marlik establish Golestan’s montage virtuosity beyond the field of word and syntax. The film’s “museum display sequences” principally consist of images of sharply lit excavated objects suspended in the air and filmed in various angles and from changing distances, at times moving and at other times static. They have an ethereal appearance against a background that is immaculately black. These museum sequences are striking in their broad array of editing and lighting arrangements, camera movements, and optical printing methods; the cinematic techniques put on display, most of them drawn from the inventory of cinematic modernism, include jump cuts, traveling shots, close-ups, extreme close-ups, stop-motion cinematography, dissolves, and fades. The “museum pieces” spread and are scattered, with or without justification from the voice-over commentary, into the rural landscape, appearing within or next to images of the villagers standing in front of their mud-brick homes. A result of these unexpected juxtapositions is a collage-like quality. In the face of this high degree of fragmentation, it is the flawless blackness of the background and Golestan’s words that conceive connection and lucidity.

In The Hills of Marlik, the image offered of (Iranian) history is one of loss and rupture. Reminiscent of Persepolis, the excavated skeletons, the ancient objects displayed on museum pedestals, and, above all, the commentary, point to a long process of destruction and decay. “History was lost, the cast became dust, and head that was the bowl of thought is no more.” The calamity, the voice-over continues, perhaps started by terror of an invasion from the outside, by a “tribe,” an “evil idea,” a “deceiving tyrant.” The gravest consequence of this history of disintegration and ruination is the disappearance of “seeing” and its interchangeable properties of “thinking” and “giving birth” (zaeeidan). But, suddenly, in the midst of this thousand-year-long destruction, the possibility of renewal. Golestan’s poetic discourse gives the promise of a life-giving force that can come, across the boundary of time, to this land. “May the ancient roots blossom again! May the god of seed salute the valley! May the eyes see! And seeing becomes life anew.”

The House Is Black (Forough Farrokhzad, 1963)

Forough Farrokhzad’s The House Is Black starts with Ebrahim Golestan’s voice. Golestan’s detached commentary offers a brief introduction to leprosy, stating that what is going to be seen is “an image of an ugliness” and a “vision of a pain.” What follows is an intricate and dense twenty-minute-long film with multiple currents and countercurrents in imagery, sound, and verbal components. We glance the people who inhabit the never-named leper colony going about their daily activities, attending classes and prayer sessions, standing still, undergoing medical treatments. With The House, Farrokhzad introduced the two elements of body and religious motifs into the Iranian New Wave. Farrokhzad reads from the Old Testament: “For I’ve been made in strange and frightening shape. My bones were not hidden from you when I was being created in the hidden, and was being molded in the bowels of the earth.” In The House the body is diseased, photographed, and in ruin. The dominant human body here is a figure of excess, its flesh either constantly in lack or in overflow. This is a body in complete alterity to that healthy productive body of progressive history, an ideal that modern Iran has been fully committed to for a very long time. The human body’s excess here is also a feature of the uncanny. A lot of things in The House cannot be explained with certainty, and to this, the foregrounding of the body element contributes. The diseased human body, then, adds to the film’s photographic realism as well as to its undoing. Like in ancient ruins, the flesh in its very materiality is a register of temporality. Through time the elements leave their marks on our bodies, and so does the process of aging. Scars leave their sign on the skin, and passage of time deepens the lines. But in The House Is Black, the life of the lepers has altered these processes. The age of many of the subjects filmed cannot be easily determined. Although there is an awareness of temporality that comes with the effects of decay, the historical trajectory that the decay has taken remains unclear.

As a lyrical avant-garde work, the body of the filmic text in The House Is Black is also a ruin. It is as though the filmic text itself, like the bodies inhabiting it, is constantly on the verge of overspill and breakage. Passing glimpses of people, body parts (or their absence), trees, water, and animals seem to have been amassed free of narrative considerations and more for rhythmic and affective impact. The sound and Farrokhzad’s voice-over contribute to the rhythm but seldom, if at all, coincide with the diegetic space. In one of the earliest scenes in The House, a man dressed in rags is shown walking back and forth in front of a building, at every few steps, reaching and touching ever so lightly the brick wall of the dilapidated structure. The facade, made of bricks and windows, stretches from one side of the frame to near infinity. Over this intriguing scene, Farrokhzad’s voice slowly reads the names of the days of the week again and again: “Saturday . . . Sunday . . . Monday . . .” and so on. The world of The House Is Black seems to revolve around the cyclical time of the myth and not a progressive one, and that, too, is a messenger of horror.

The Wind of Jinn (Nasser Taghvai, 1969)

The 1969 documentary The Wind of Jinn, by Nasser Taghvai, brings together our two themes, the ruined built structure and the body. The Wind of Jinn’s opening scene is of waves from the sea hitting a harbor town that appears to be emptied of its inhabitants. Mixing with the sound of waves is the sound of wind. The voice-over, this time belonging to Ahmad Shamlou, an icon of modern Persian poetry, gives somewhat of an introduction to the place. “In the broken and ruined port of Lengeh still comes the sound of relentless battle, of waves and the rocks of shores without men.” What follows are shots of decaying buildings, alleyways, and dusty cemeteries. With the images of ruination, the soundtrack picks up a lullaby in a mournful female voice (remarkably reminiscent of Rahnema’s Persepolis). Here, too, as in The Hills of Marlik and Persepolis, the ruin simultaneously points to a past synonymous with life and to the long process of decay that has followed.

The male voice-over’s grieving is also for the “Southern Blacks” and their pains. The Winds, specially the one called the Wind of Jinn, are said to be responsible for the outburst of untold maladies among the remaining populace as well as for the destruction of the port city. Amid the death and decay, though, the locals have found the remedy, a gift deposited within those who (reportedly) have come from the shores of Africa. It is not that the Winds did not exist before the arrival of the Africans, as the commentary intriguingly discloses, but that they had remained “unknown,” “like the power in a diseased body, like the oil under the sea, like consciousness in the head of the uncultured.” The Winds have existed for a long time but they needed the “tradition of the Black” in order to become known, as that tradition was able to recognize the “resemblance” and become the healer. The healing was in mimesis.

From its highly fragmented early scenes of fallen alleyways and objects, The Wind of Jinn moves on to a relatively long possession/exorcism sequence. If so far the film has been finding pleasure in the haunting beauty of open spaces, of stormy seas and deserted shores, with the possession scene we move into the closed space of a crowded room. Slowly some in the group start to move to the center of the room, their bodies convulsing at an increasing rate. Cutaway shots to the ruins outside interrupt the flow of the visual and soundtracks alike. Is there a link between the two? Others in presence stand to shroud the bodies of those in trance, to assist and comfort them, covering them with white sheets. The film ends with a shot of a man wrapped in the middle of the room, as the lullaby we heard earlier returns.

Arbaeen (Nasser Taghvai, 1970)

The young director of The Wind of Jinn made a number of the most influential documentaries of the New Wave, some of which are among the best representatives of the subgenre of ritual films, a category that centers on bodies more than others. Taghvai’s Arbaeen starts with a slow zoom in on an illuminated object in the middle of a large room, a small replica of a Shia shrine. The music has already started and the image cuts to a small dusty back alley where men are beating on large drums. Arbaeen is going to be the first documentary discussed in this essay that does not have a voice-over commentary. Until this point, the camera is handheld and the whole scene has a rather informal touch. Then, suddenly, as soon as we might think we are seeing an Iranian equivalent of direct cinema, another scene opens that launches the film’s predilection for fragmentation and stylization. An abrupt cut to a black fabric edged with flowers and Qur’anic scripture is followed by a quick succession of shots of stained glass. These backlit glass windows, perfectly symmetrical and two-dimensional, appear to be suspended against the pitch black framing them. This “stained glass segment” in Arbaeen corresponds with what I refer to as the “museum aesthetics” of the New Wave.

Soon after, the scenery changes to a large, brightly lit interior, and the ritual sequence, or what I see as the film’s “body sequence,” begins. In contrast to the streets outside, the interior space is male territory. Its inhabitants form circles around circles, each with one hand holding the next person in line, and with the other, beating his bare chest in a steady beat. In this sequence, by far the longest in the film, the human body not only becomes central thematically, it also bursts onto the screen in its very materiality. With the arrival of this sequence, the film’s rhythm slows down; longer takes take precedence, and the camera’s gaze follows the mourners. Longer duration of the shots and their deep focus allow the viewer to see significantly more. This affirmation of the visual evidence becomes even more intimate as the camera slowly moves closer and closer to the center of the room and among the men engaged in the ritual. Different body types, skin textures, muscle contractions, the shine of sweat, bodily eccentricities, occasional tattoos become visible. As the men beat their bare chests, the redness of the skin where their hands hit comes into view. Moreover, this act of hitting the upper body, simultaneously measured and improvisational, personal and collective, produces another effect, a rhythm. The rhythm generated here, itself in a “dialogue” with the sad lament sang by the singer, sets the tempo for the group’s movement in the pro-filmic world and, in turn, informs the pace of the film. Both the activities of the crew at the moment of filming, as Jean Rouch’s utopian ideas on cine-trance remind us, and the choices made at the editing table are affected by the sounds and movements produced by the bodies of mourners, in a somewhat diffused form of materiality proclaiming and “redeeming” itself. That bodily movements and sounds produced by the “subjects” being filmed have an impact on the documentary/ethnographer filmmakers (sound as well as filming crew) might be by now a part of an old wisdom, an old wish of the participatory cinema and its kin in the ideal of “shared anthropology.” The idea is still alive, though, even if we only take up Rouch’s thesis on “cine-trance” at its minimum reach, and not its maximalist dream of complete dissolve in the native’s ritual.

In Arbaeen, nonetheless, the movement toward more detail and visibility is paralleled by something different: a drive toward fissure and instability. As the ritual continues, as the mourners’ circular movement intensifies, the camera gets closer and closer to its subjects. As expected, this closeness first brings more clarity of sight, which can continue only to a point as, after a while, the now fast-moving hands and torsos start to fall out of focus and become a blurred mass. This arrangement of bodies enmeshed into one another, organized in tight circular lines ringing other circles made of human forms, as though in a whirlwind of flesh, becomes a visual celebration of the possibility of collectivity.

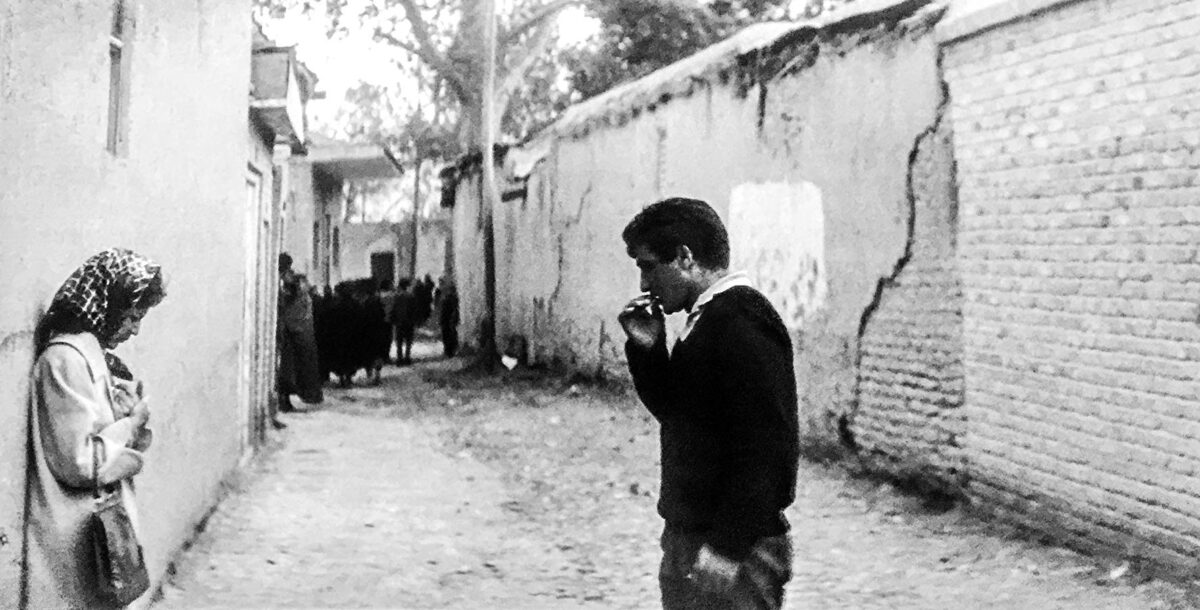

The Brick and the Mirror (Ebrahim Golestan, 1964)

Already well-known as a writer, photographer and documentary filmmaker Ebrahim Golestan made his first fiction feature The Brick and the Mirror in 1964. The film opens with a long take of a busy Tehran street, the only thing visible at night, the city’s lights and cars in sharp black and white. What follows is a long driving sequence. Passing cars, flickering streetlights, rotating neon signs, their hazy reflections. The driver switches between radio stations. As the car travels through the city, it is called over by a female voice: “Taxi!” The driver pulls over and a woman covered in a black chador, played by Forough Farrokhzad, gets into the back seat. The destination turns out to be a faraway neighborhood, desolate, only half-built and half-lit. The car stops on a road next to a mud-brick wall. When the woman exits and disappears into the night, the driver realizes that she has left behind a child. He runs into the thick of the dark and enters what appears to be a ruined building. This desolate structure is inhabited by three ghostly characters: an older woman, a disabled man, and a pregnant woman. The older woman is waiting for her son to come back, the younger woman is languishing in the dream of her husband’s return, and the disabled man, too, is hoping that the older woman’s son, “his friend,” is going to come back one day. At the same time, the first woman seems to believe in something else: “Here is a ruin. Nobody comes here.”

But the ruin in The Brick and the Mirror is a ruin with a difference. Golestan, on different occasions, has used the same term, as in a booklet accompanying the film’s release, while also contesting the designation at other times by insisting that it was an “unfinished home.” This inconsistency is perhaps a continuation of the larger semantic uncertainties of the ruin as an idea, a representation, and as a material formation. The discrepancy we face in the accounts of the building in this most hard-to-pin-down scene in The Brick and the Mirror might not be a bad thing. Between a ruin and an “unfinished home” is, in their existence in the lexicon and beyond, I believe a built-in tension that when further aggravated will bear good results for critical analysis.

An unfinished structure looks to the future. That is to say that it is shadowed by a particular, more flamboyant futurity invested in the site from the moment its material construction begins. An unfinished building is not only different from the ruins of antiquity (like Persepolis in Rahnema’s documentary) but also different from the ruins with chronicles of ruination falling within modern times in one way or another. The unfinished structure, unlike other ruins of modernity, has hardly had its chance under the sun to experience the effects of decay and destruction, natural or otherwise.5Exceptions do exist, and Iran again provides us with one as in the case of the building projects from the Pahlavi era that were left unfinished for a decade, if not more, after the Revolution.

Rendering an unfinished building as the ruin, in naming, in conception, contains within it a buried critique of the original project of chronological progress. If the classical ruin in its romantic representation stands as a testimony to the transient nature of history, the unfinished structure as ruin points to the blind eye of the faith in the future. If, as Golestan insists, the building in The Brick and the Mirror’s ruin scene is “a home unfinished,” it is one with all its deformities, in fact stillborn. The stairways cut across darkness, connecting the different floors, the driver with the child in his arms traverses them, only to find out that each layer holds very little except stories of separation. The old woman, her figure and voice progressively disembodied:

Poor souls, they still are hopeful.

But nobody is coming back.

Here was once farmland.

One day they came and sold it all.

The wheat and barley were ready to seed.

But one day they came

with steel.

The ruin scene in The Brick and the Mirror, standing somewhat apart from the film’s plot and overall style, might be the only passage in the film conjuring a pre-urban past and, in so doing, carries a particular weight. The unfinished structure built on farmland is now standing on the edges of an ever-expanding metropolis. The walls of the city that emerged from the destruction not only divided people from each other but also discursively fractured the temporality of the place. The two distinctive worlds created live simultaneously side by side in their materiality as well as, ethereally, in memory.

In Tehran, too, the country plays hide-and-seek with the city, as Walter Benjamin once observed on Moscow.6Walter Benjamin. Moscow Diary, ed. Richard Sieburth, trans. Gary Smith (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1986), 67. The perception that the great metropolis by the Alborz mountain range is divided by a multiplicity of temporal planes finds its most well-known dualistic manifestation in the division between the South and the North. In many regards, this is a split that projects inward the already existing division between the rural and the urban. The “south of the city” stands for the working class, underdevelopment, narrow alleyways (koochehs), buildings in decline, mosques and calls to prayer, men with black open shirts, fallen women, women with chadors, camaraderie, but also poverty, lonely souls, crowds, and crime. South of the City was also the name of a 1958 film by Farrokh Ghaffari, a film that could have been regarded as the Iranian New Wave’s first fiction feature if its negatives had not been destroyed by the authorities.

The Brick and the Mirror ends where it begins, on a busy street with a woman in a black chador calling, “Taxi!” It is getting dark and Hashem is sitting behind the wheel of his car. But right before the final scene, there is another scene. In this scene before the last, the female protagonist enters the orphanage where, earlier in the day, her lover had abandoned the child. Inside she discovers countless little children on different floors. Some in groups on the floor, some in tightly set rows of beds, some smiling, some crying. Most look back at the camera. Many of the kids have an unusual repetitive body movement, back and forth, back and forth. With these images of entrapment and anguish it is as though The Brick and the Mirror opens a door to The House Is Black.

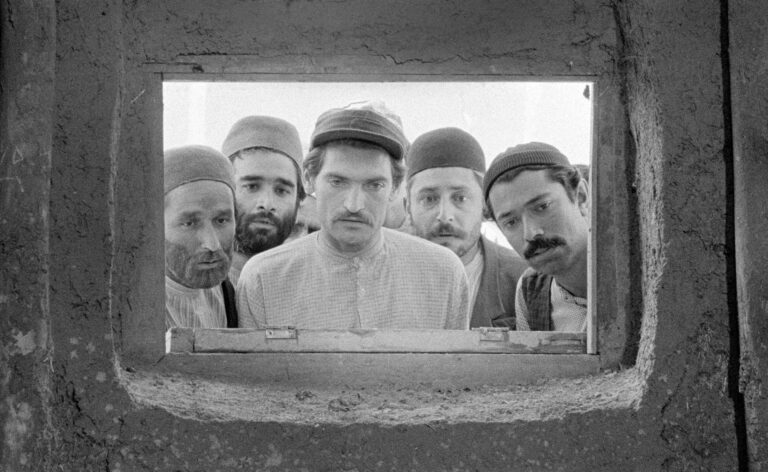

The Cow (Dariush Mehrjui, 1969)

Then, in The Cow I moved a little more daring and fearless. In The Cow I was even able to create metaphysical and surreal ambiences, or the ambience of meaningful silences. —Dariush Mehrjui7Esmael Mihan-Doost, Jahan-e Now, Sinema-ye Now: Goftegoo ba Kargardanan-e Sinema-ye Iran [New World, New Cinema: Dialogues with Directors From Iranian Cinema] (Tehran: Nashr-e Cheshmeh, 2008/1387), 16.

The most celebrated film of the Iranian New Wave until not long ago, Dariush Mehrjui’s The Cow has a simple narrative. 8The filmscript is based on a story from The Mourners of Bayal (1964) by Gholam-Hossein Saedi, a well-known author of fiction and stage plays. He was also a passionate producer of folklore studies and ethnographies. G. Sa’edi, The Mourners of Bayal: Short Stories by Gholam-Hossein Sa’edi, trans. Edris Ranji (Bethesda, MD: Ibex, 2018). Published in its original language in 1964. It is a story of a village, unnamed and unlocated, a man living in that village called Mashhadi Hassan, and his cow. One night when he is away, his cow dies. The villagers at first try to hide the bad news from him but to no avail. Mashhadi Hassan metamorphoses into something new, something frightening. In both its narrative and its visuality, The Cow shows a disposition for shedding the “nonessential” to the point that only the formative outlines of the story or image remain. Instead of resulting in simplicity, however, the film’s fascination for austere structures produces a form of stylization.

These austere sets, especially those in the exterior shots of the village, contribute greatly to the film’s particular and hard-to-forget look. 9The title sequence credits Ismael Arham Sadr, a set designer and actor active in theater and cinema, for the film’s “Décor.” The walls, the houses, and the alleys they create, are made of mud bricks covered with a coating of mud plaster. This adobe material is formed into smooth curvaceous surfaces. The adobe soil is of course a common element used in buildings in Iran (and around the world). It is used as bricks and plaster. Until recently, in rural Iran particularly, unbaked soil mixed with dry hay was the basic building material (called kah-gel). In their earthlike tone and texture, and in their association with the homes of the “down-to-earth people,” these materials of construction stand for authenticity in architecture and in culture. In many of the New Wave films shot in the countryside, mud bricks and mud plaster are inevitably part of the scenery; in that, Mehrjui’s The Cow is an exception only because of the overwhelming degree of this visibility of earth, mud, and dust.

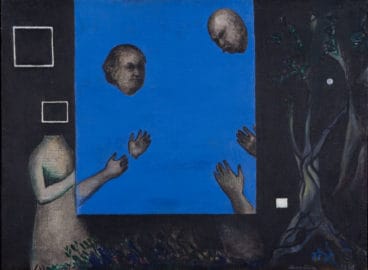

Even before Mehrjui made his classical New Wave film, the adobe earth had entered, discursively and in its very physicality, the world of Iranian visual modernism. Marcos Grigorian (1925–2007) stands as a great example. A graduate of Rome’s Accademia di Belle Arti, Grigorian returned to Iran in 1954 and immediately became influential as an artist, teacher, and gallery owner. He was among the earliest proponents of “traditional” and “naïve” creative practices like the local popular genre known as “coffee house painting,” which often uses themes and motifs from Persian literature and mythology as well as Shia hagiology. The soil, in which dissolved the expressionism of Grigorian’s early years in Italy, became increasingly important in his milieu from the early 1960s onward, the time span that also saw the emergence of the New Wave. This creative use of Iran’s “parched earth and mud” by Grigorian can be seen in such works as Kharg Island (1963), Spiral (1967), and Desert (1972), eventually culminating in a series entitled Earthworks. Made out of adobe soil, at times mixed with dry hay, that other old-fashioned building material, Grigorian’s Earthworks are distinguished by a minimalism that allows the texture of the adobe, cracked and rustic, to come to the fore. At the same time, the compositional sparseness takes in simple rectangular or curved shapes. Rectangles framing other rectangles and circles.

Image courtesy the author.

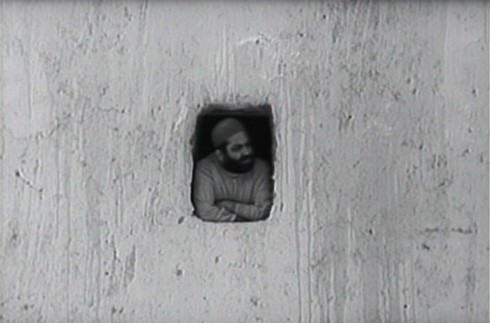

Curvaceous and symmetrical at the same time, the sunbaked walls and rooftops of the “décor” in Mehrjui’s film have a pronounced presence in most of the scenes. The characters of the story, the villagers, are filmed against them, more often in frontal tableau-like shots. The facades of the humble homes crafted out of these adobe walls and roofs are also symmetrical, complicated by curves of windows and arches. Though time after time, through cinematography and lighting, the surfaces of the buildings are framed in such a manner as to separate them from their surroundings, a strategy that creates geometrically minimal graphics. Unlike in Grigorian’s paintings/installations, in Mehrjui’s films the rectangular orifices of windows and doors constantly slip into the narrative as openings into other spaces. Within multiple mediums, whether on celluloid, on the walls of country homes, or on the walls of art galleries, this quotidian building material was entangled with a literary-ethnographic register.

The transmutation that the grieving Mashhadi Hassan undergoes is of the most radical form, affecting him both within and without. It is a source of unimaginable agony for him and the people around him, and it places the film’s narrative on a new, unexpected course. When he is told of his cow’s death, Mashhadi Hassan refuses to accept the calamity and begins to change. He becomes the dead animal. An inventory of bodily excess is put on display, rolling eyes, crying aloud, head hitting against walls, eating cattle feed, howling. Is this a story of a spirit possession or one of a metamorphosis? Part of the strangeness of the film comes exactly from the tension between these two modes of alterity-becoming, from the fact that it is both. Like in possession/trance films, Mashhadi Hassan’s condition finds its primary medium in the body. If mimesis in possession rituals is a performance/dance of empowerment over an alterity (à la Michael Taussig), in The Cow it leads to the horrors of alienation.

Soon after the release of The Cow, in 1971 Mehrjui made The Postman (Postchi) based on Georg Büchner’s stage play Woyzeck. The story of The Postman takes place in the countryside, unfolding, at least on one level, along a country-city schema. This is a dynamic that is also at play within the two other features directed by Mehrjui before the Revolution, Mr. Simpleton (1970) and The Cycle (1974). In all of these films made after The Cow, a major part of the tragedy, the modern horrors befallen on the characters’ lives, comes not just from the opposition between the country and the city, but, more exactly, from the predestined victory of the latter over the former. The Cycle, based on a script cowritten with Saedi, is yet another celebrated film of the New Wave taking up the tragic theme of the arrival in Tehran. The film begins with images of a young man and an ailing old man against an industrial landscape and ends with the son looking on as his father is buried in a desolate landscape. What takes place in between is the story of their fall, physical and moral, in an urban scene overwhelmed by deceit and corruption.

Film and History in Pieces

Ruins are at the heart of Kimiavi’s cinema, including in The Mongols, the film with which we opened this essay. They are the sites of illegal excavations, where the Mongols, invaders from another time and place, first arrive in the flesh. The landscape, at once breaking into the vision of the filmmaker-turned-protagonist (played by Kimiavi himself, you remember) and into the body of the film, is mainly made of sand dunes minimal in composition and colors, and the scattered, decaying ruins of mud-brick structures. There is also a guillotine, a device more associated with modern France and its terrors than with the Mongol armies of the past, but also the capacity of the cinematic apparatus for cutting and montage. In some shots, the blade of the guillotine is replaced with a TV monitor, as the filmmaker lies down in the place of the condemned.

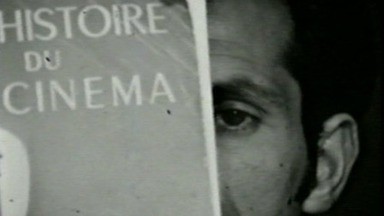

Kimiavi had engaged before with the imagery of archaeology and museums, the two closely related material formations with the New Wave from its inception, shaping its thematic and aesthetic contours. In 1969 his highly playful and lyrical documentary The Hills of Gheytarieh begins with these words: “We are in touch, with the world of the dead, with those who were lost in history. We renew our historical affinity.” Produced by National Iranian Radio and Television, it is a film that brings together excavation scenes and museum imagery (as did The Hills of Marlik before it). The film depicts an excavation team at work at an archaeological site. Batches of three-thousand-year-old artifacts are unearthed in pieces and then put back together. Meanwhile, in a movement in reverse, the film breaks up the pro-filmic world and then reassembles it. Showing a degree of self-consciousness and autocriticism both toward the medium of cinema and what we now call the heritage/memory industry, The Hills of Gheytarieh takes up an ironic tone in its museum scene, evoking an art auction through its accompanying soundtrack. The critical angle, however, is more apropos to the loss of “authenticity,” indeed, the loss of “life” of the appropriated artifacts.

The last things before the last. In The Mongols, excavating old artifacts includes unearthing old film and media. In many ways a found-footage film, the images are taken out of their contexts and reassembled. We see men dressed in some local attire from the eastern parts of Iran digging holes in the ground in search of ancient artifacts and, suddenly, the Mongols. The film’s treatment of film history moves in parallel to what these men are doing, back in time, as a form of excavation of “primitive” relics. So what comes to the fore, breaking the continuity of the present time, is an onslaught from the cinema’s primal years and the precursors to the apparatus: Eadweard Muybridge’s horses and men; Georges Demenÿ uttering, “Je vous aime!” in 1891; and William Kennedy Dickson’s The Gay Brothers (c. 1896), among others. The ancient relics taken out of the dry earth and the earliest moving images of history emerge, in Raymond Williams’s prediction, as “sources and as fragments against the modern world.”10Examining the “range of basic cultural positions within Modernism,” Williams includes “conscious options for past or exotic cultures as sources or at least as fragments against the modern world.” See Raymond Williams, Politics of Modernism: Against the New Conformists (London: Verso, 1989), 43.The newness of media, like television and cinema before it, are confirmed (in their impact) and thrown into question (in the recurrence of their forms and conditions). Film and media archaeology before its time.

Photograph by the author.

In Memory of Dariush Mehrjui (1939-2023).

This article is published in conjunction with the most comprehensive survey of Iranian pre-revolutionary cinema ever assembled in North America, “Iranian Cinema before the Revolution, 1925-1979,” on view at MoMA in October and November 2023. The series is organized by guest curator Ehsan Khoshbakht, Codirector, Il Cinema Ritrovato, with Joshua Siegel and La Frances Hui, Curators in the Department of Film at MoMA.

- 1For more on Kracauer’s engagement with MoMA’s Film Library, established in 1935, see David Culbert, “The Rockefeller Foundation, the Museum of Modern Art Film Library, and Siegfried Kracauer, 1941,” Historical Journal of Film, Radio, and Television 13, no. 4 (1993): 495–511. Other film historians and theorists who worked with the Film Library, before there was an academic discipline called “Film Studies,” include Jay Leyda, Paul Rotha, Fernand Léger, and Luis Buñuel.

- 2For more extensive and in-depth variations of the analyses presented here, see Farbod Honarpisheh, “Fragmented Allegories of National Authenticity: Art and Politics of the Iranian New Wave Cinema of the 1960s and 1970s” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 2016).

- 3Georg Simmel, “The Ruin” (1911), in Essays on Sociology, Philosophy and Aesthetics, ed. Kurt H. Wolff (New York: Harper and Row, 1965), 260.

- 4Simmel, “The Ruin,” 260.

- 5Exceptions do exist, and Iran again provides us with one as in the case of the building projects from the Pahlavi era that were left unfinished for a decade, if not more, after the Revolution.

- 6Walter Benjamin. Moscow Diary, ed. Richard Sieburth, trans. Gary Smith (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1986), 67.

- 7Esmael Mihan-Doost, Jahan-e Now, Sinema-ye Now: Goftegoo ba Kargardanan-e Sinema-ye Iran [New World, New Cinema: Dialogues with Directors From Iranian Cinema] (Tehran: Nashr-e Cheshmeh, 2008/1387), 16.

- 8The filmscript is based on a story from The Mourners of Bayal (1964) by Gholam-Hossein Saedi, a well-known author of fiction and stage plays. He was also a passionate producer of folklore studies and ethnographies. G. Sa’edi, The Mourners of Bayal: Short Stories by Gholam-Hossein Sa’edi, trans. Edris Ranji (Bethesda, MD: Ibex, 2018). Published in its original language in 1964.

- 9The title sequence credits Ismael Arham Sadr, a set designer and actor active in theater and cinema, for the film’s “Décor.”

- 10Examining the “range of basic cultural positions within Modernism,” Williams includes “conscious options for past or exotic cultures as sources or at least as fragments against the modern world.” See Raymond Williams, Politics of Modernism: Against the New Conformists (London: Verso, 1989), 43.