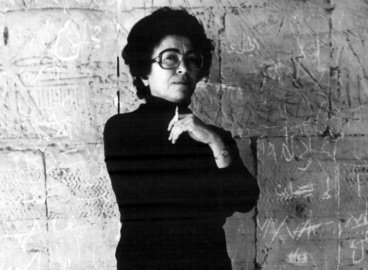

Evelyn Ashamallah (born 1948) presides over history from her small apartment in Talaat Harb in downtown Cairo.1Unless otherwise indicated, all personal accounts from Evelyn Ashamallah were gathered by the author during discussions with the artist in the fall and winter of 2024–25. Across the past six decades, she has demonstrated a legacy of constant negotiation between political ruptures, sanctioned and unsanctioned histories, as well as grounded and wayward mythologies. Ashamallah’s paintings and drawings are not easily characterized in the 20th-century binary frameworks of traditional versus modern, romanticism versus social realism, or local versus national. Instead, her oeuvre straddles the contradictions present in Egypt’s postcolonial era. Through all the shifts that rocked Egypt’s transition into modern statehood, Ashamallah’s ongoing artistic practice has wrestled with the inconsistencies of history that bear so heavily on our shared present.

Ashamallah was born in 1948, the year of the Nakba or “catastrophe,” a paradigmatic rupture that would change the course of history and redefine the trajectory of Egyptian nation-building.2According to Rabea Eghrabiah, “Meaning ‘catastrophe’ in Arabic, the term ‘al-Nakba’ (النكبة) is often used—as a proper noun, with a definite article—to refer to the ruinous establishment of Israel in Palestine. A chronicle of partition, conquest, and ethnic cleansing that forcibly displaced more than 750,000 Palestinians from their ancestral homes and depopulated hundreds of Palestinian villages between late 1947 and early 1949.” Eghrabiah, “Toward Nakba as a Legal Concept,” Columbia Law Review 124, no. 4 (2024), 889, https://columbialawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/May-2024-1-Eghbariah.pdf. See also Lila Abu-Lughod and Ahmad H. Sa’di, “Introduction: The Claims of Memory,” in Nakba: Palestine, 1948, and the Claims of Memory, ed. Ahmad H. Sa’di and Lila Abu-Lughod (Columbia University Press, 2007), 1–24; and “About the Nakba,” in “The Question of Palestine,” United Nations website, https://www.un.org/unispal/about-the-nakba/. Her life thereafter has been decidedly marked by events that punctuate the making of modern Egypt. Like many Egyptians, her sense of time is structured by presidential eras (Nasser, Mubarak), wars (the Six-Day War, Al Naksa, the War of Attrition), and agreements (Camp David, Oslo). These sweeping, large-scale, political shifts have reverberated in Ashamallah’s private life. Indeed, President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s nationalization policies impoverished her formerly middle-class family, and her brother’s martyrdom in the 1967 War of Attrition is a tragedy that has deeply afflicted her.

Ashamallah grew up in Desouk, a provincial town in the Egyptian Nile River Delta region of Kafr-el-Sheikh, amid rural traditions that continue to influence her painting and drawing today. Though her Christian family was not originally from this region, they lived in Desouk because her father was assigned there to oversee life insurance policies. At home, her father’s library was rich with literature, which she pored over. Outside, she climbed sycamore trees, befriended the local livestock, and sang folk songs with the neighboring children. She planted rice and other seeds on her aunt’s land, fascinated by watching how plants grow and yield fruits for picking. Today, her imagination is still populated by the creatures, real and invented, that inhabited her early childhood.

Against Canonization

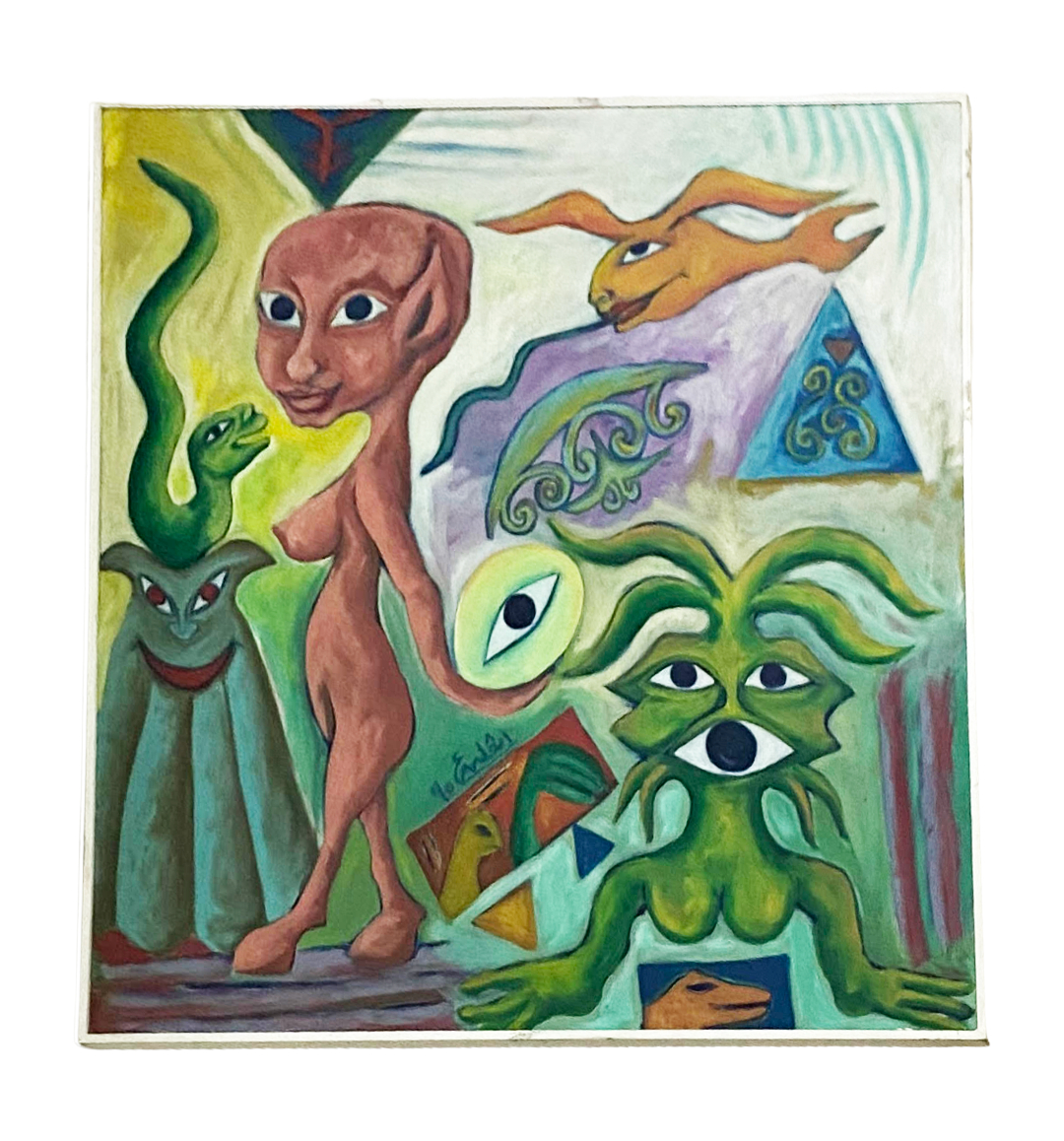

When prodded about the imaginative tropes in her work, Ashamallah sings a song that the village women would sing in a processional held at night during the lunar eclipse. Her artwork, which contains elements from Egyptian folklore and Pharaonic motifs—often hybridized alongside figments of her own imagination—offers novel interpretations of traditional forms. Ashamallah’s apartment is filled with paintings, and one that stands out is Hathour and Her Egg (1995), a large, prominent portrayal in her living room of the Pharaonic goddess Hathour (fig. 1). Ashamallah has been consistently preoccupied with the female figure and feminine prowess, as is evident in her depiction of Hathour, mother of all the Pharaohs and a goddess who represents the sky, motherhood, fertility, beauty, music, and joy. When asked what inspires these figures, she recounted a pivotal discovery: that the female mantis eats her partner by decapitating it after they have mated. Though Ashamallah did not elaborate further, it makes sense that the violence and beauty inherent to the natural process of mantis-mating could have inspired her to depict insect-like creatures as well as women with plants or other creatures inside their bellies. For Ashamallah, the female body is the touchstone of creation, the alpha and omega.3For more on the role of the mantis within the Surrealist tradition, see Ruth Markus, “Surrealism’s Praying Mantis and Castrating Woman,” Woman’s Art Journal 21, no. 1 (2000): 33, https://doi.org/10.2307/1358868.

It is challenging to attach Ashamallah to a particular school or “ism”—Expressionism, Primitivism, Surrealism. Instead, she weaves in and out of these styles at whim, eluding categorization by reworking forms that present her unique worldview. Though she received highly formal Beaux Arts–style training, she often surrenders her traditional education to follow the lead of her imagination. Her compositions present the world as she remembers it: full of trials and tribulations and marked by the simultaneity of euphoria and desolation. As an artist, her confidence in her own vision has always been steadfast. She recounts being on a field trip in middle school and visiting the Fine Arts Library. When her friend asked her, “Have you seen Picasso?” she responded, “Who is Picasso? I am Evelyn Ashamallah.”

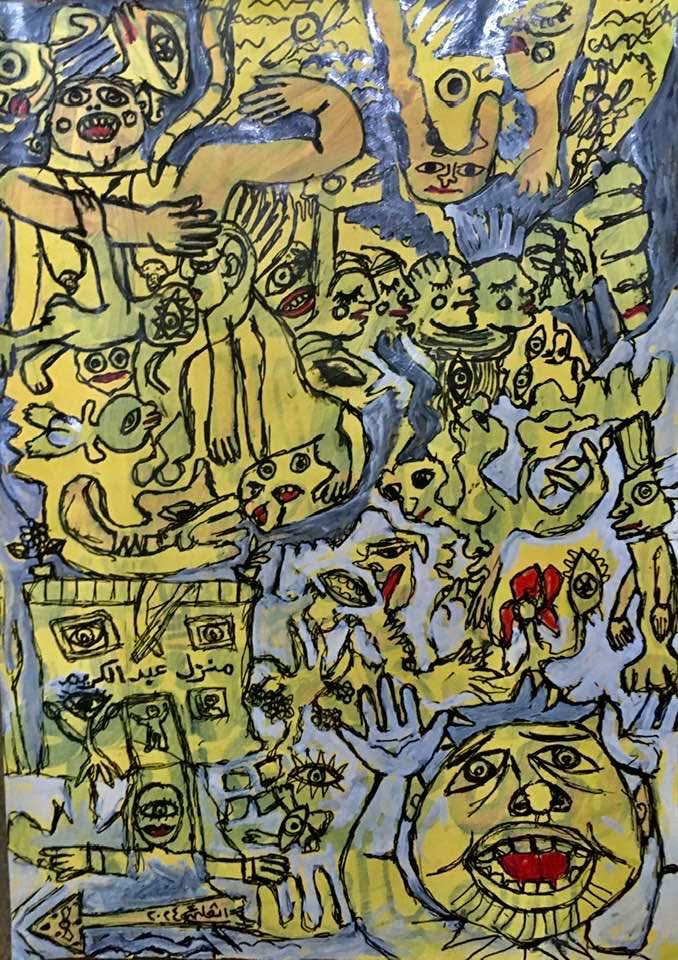

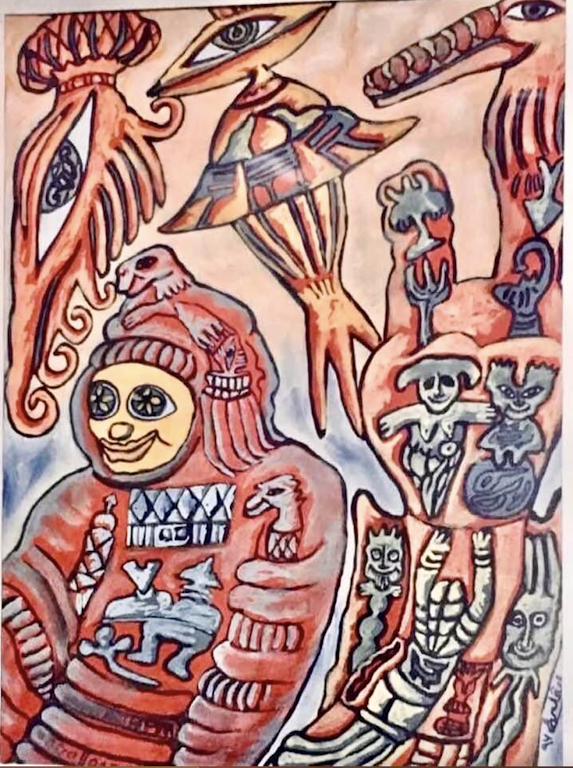

Her politics are seldom explicitly manifest in her artwork, though on certain occasions, she has illustrated specific political events, such as the 1982 Sabra and Shatila massacre or the ongoing genocide in Gaza (fig. 2). Nevertheless, most of her paintings and drawings are not didactic. When looking back on her body of work, it is difficult not to read certain pieces as parallels to the large-scale political transformations taking place in the background at the time they were made. Compositions featuring peasants tilling their land or astronauts (fig. 3), aliens, and UFOs evoke societal changes such as the 1952 Land Reform Law, which redistributed Egypt’s arable land, or the establishment of a national space program in 1960.

As a young artist, Ashamallah found herself caught in the 20th-century gestation of a new republic. She graduated from the Painting Department of the Faculty of Fine Arts in Alexandria in 1973 and then moved to Cairo. There, not yet fully embracing her painting practice, she worked as a journalist for Rūz al-Yūsuf, a weekly political magazine that had just begun distribution in the Gulf countries. Her first piece, published in August 1973, was on the bride economy between the Gulf and Egypt. As an investigative journalist, she shed light on cases of newly wealthy Arabs from Saudi Arabia and the Emirates who would come to various rural places across Egypt and purchase young girls to bring home as wives. After this fearless debut, she earned a living by writing similar political, investigative editorial pieces until a disagreement with her editor led her to find work elsewhere. In 1977, the Egyptian government issued a warrant for Ashamallah’s arrest for her alleged involvement in leftist political activity. Forced to leave the country until they were no longer targets of the Egyptian state, she and her husband, journalist Mahmoud Yousri, moved to Algeria, where they lived in exile for six years. While she would not return to journalism, she was always involved in her husband’s editorial work and has remained an avid writer. Later in her practice, she began incorporating her writings into her artwork.

During one of our interviews, I asked Ashamallah about her relationship to politics after the 2011 uprising in Tahrir Square, in which she played a prominent role as a leading dissident and organizer. She discussed how, in retrospect, almost fifteen years later, she sees “how naive and blind we were, how we didn’t understand anything.”4The Tahrir uprising on January 25, 2011, included a massive public demonstration demanding democracy and an end to President Hosni Mubarak’s 30-year rule that evolved into an 18-day occupation of the square, with protesters facing tear gas and violence from security forces. It culminated on February 11, 2011, when Mubarak resigned, handing power to the military. For more on this subject, including a historicization of protest movements in Egypt leading up to January 2011, see Bahgat Korany and Rabab El-Mahdi, eds., Arab Spring in Egypt: Revolution and Beyond (American University in Cairo Press, 2012). Now, after a lifetime of involvement in different political groups—ranging from leftist to Marxist to Socialist to Communist throughout regime changes and political fluctuations—Ashamallah wants her artwork to be free of political determinations and social burdens. As she explained to me, “They’re free to politicize whatever they want. For me, what do I do? What is good for me to do? I paint. Let me paint.”5Evelyn Ashamallah, in discussion with the author, October 29, 2024.

Exile and Early Drawings

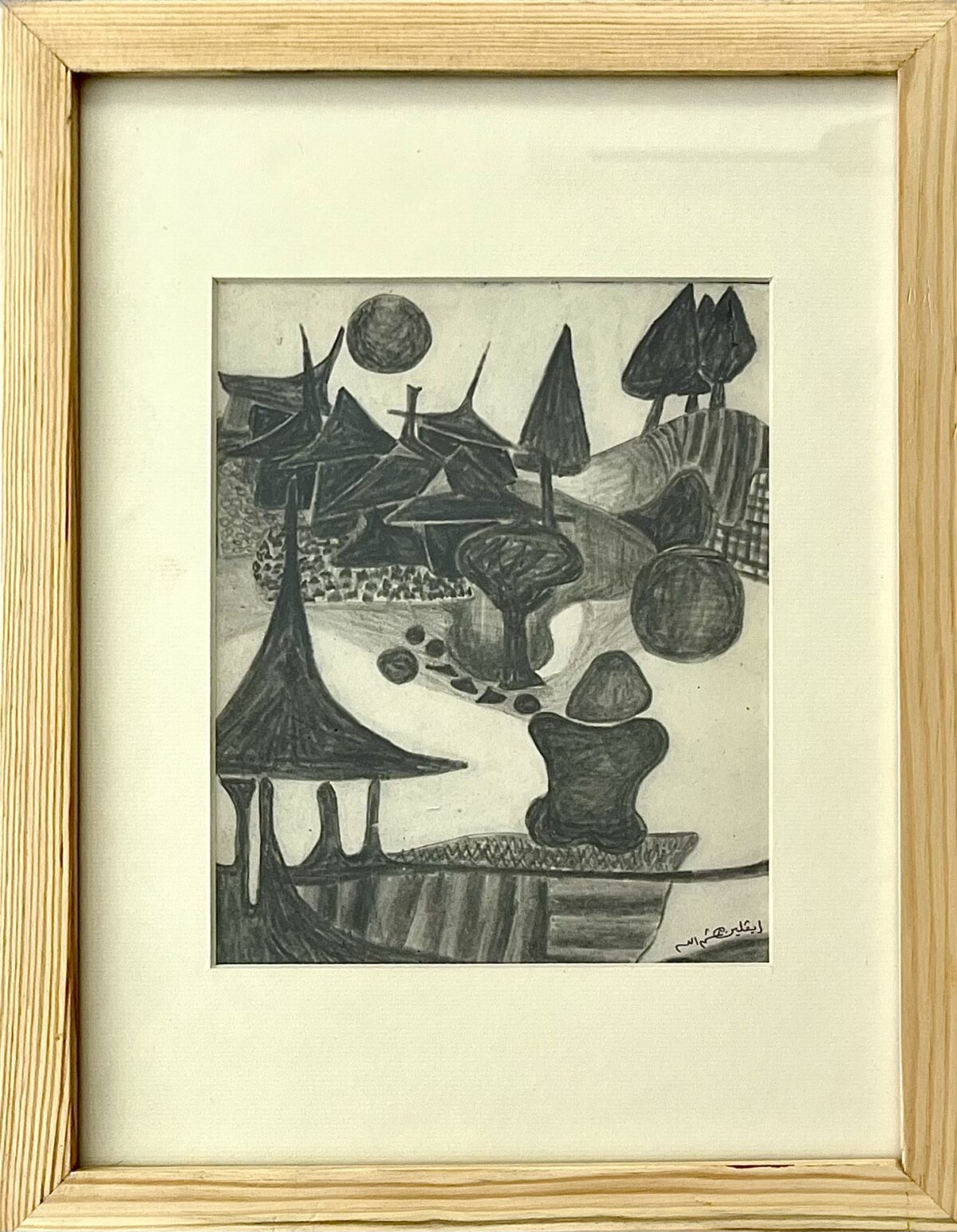

In our discussions, Ashamallah referenced multiple times how the farmers’ fields inspired her developing visual language as a young girl.6Translated from the Arabic غيطان الفلاحين Despite this, she did not demonstrate interest in landscape painting while a student in Alexandria. Instead, she preferred riding the tram all day long and watching—and drawing—the hustle-bustle. It was not until she arrived in Tiaret, Algeria, in 1977 and encountered the topography of the agricultural province that she began drawing landscapes. Before traveling to Algeria, she had never seen such majestic hillsides. Given the flat, agricultural lands of her childhood, she was captivated by the different elevations in her first landscapes, which are often rendered in flat compositions with multiple planes stacked on top of each other. This compositional structure has remained present throughout her work, as she still typically divides the surface—whether cardboard, canvas, or paper—into sections that she then populates with original forms.

Landscape in Algeria (1980) is made of quasi-organic, geometric shapes that are common in her other illustrations from this time (fig. 4). Inspired by local crafts within the Amazigh tradition, Ashamallah borrowed certain forms that suited her desire to blend human figures with bushes, and trees with architecture. This hybridization is a constant throughout her artistic practice, whereby people are depicted with plantlike traits, and animal-creatures float in boundless spaces, undisturbed by the laws of perspective or gravity.

In Algeria, Ashamallah’s husband only found sporadic work as a schoolteacher, and so they struggled to make ends meet. Though she never stopped drawing (“not even for one day”), it was a rare joy for her to receive colors, and when she did, she gravitated toward the saturated tones that she would later use in her acrylic works.

When they moved from Tiaret to the capital of Algiers, Ashamallah developed a tight-knit community of friends from the political, intellectual, and artistic milieus across the Arab region—Syria, Palestine, Iraq, and, of course, Algeria. She was influenced by many of the conversations that took place at this time. The Algerian modernist artist Mohammed Khadda states in his essay “Elements for a New Art,” which he wrote fresh out of the Algerian War (1954–62) in 1964, “Our country is taking the socialist path, and the artist—like the worker and the peasant, has a duty to participate in the edification of this new world, in which man will no longer exploit man.”7Mohammed Khadda, “Elements for a New Art” [1964], in Modern Art in the Arab World: Primary Documents, ed. Anneka Lenssen, Sarah A. Rogers, and Nada M. Shabout (The Museum of Modern Art, 2018), 232. Though Ashamallah never directly references Khadda—except for in a side conversation in which she notes his calligraphic forms with admiration—it is clear that Ashamallah shares some of the concerns he waged in the formation of the new independent Algeria. She was inspired by the goings-on around her and has spoken extensively about the importance of her time in Algeria in her personal life and artistic trajectory.

In 1984, Ashamallah returned to an Egypt that was fundamentally different from the country she had left: one that was rife with economic disparity, increasingly common sectarian clashes, and a new age of political repression under the leadership of President Hosni Mubarak. Nevertheless, determined to support her children and continue making art, Ashamallah engaged with formal cultural apparatuses, staging exhibitions in state-run venues such as the Cairo Atelier (1986), among others. In the 1990s, she served as director of the Mohamed Nagy Museum in Giza before becoming director of the Museum of Modern Egyptian Art in Cairo. In 2011, she left this post, emphatically exposed the corruption within the Ministry of Culture, and took to Tahrir Square.

The Rural Trace

Now, as Ashamallah has lived longer in the dense urbanity of Cairo than in its rural environs, she continues to derive inspiration from the landscape that defined her youth. It is there that she identifies the “Egyptian spirit” in its truth and essence. This portrayal of the rural as the “essence” of the nation, and the peasant as the “true Egyptian,” defined art historical, literary, and political debates in Egyptian modernism throughout the 20th century. In 1911, the newly established Egyptian Faculty of Fine Arts opened with a European curriculum and the following aim: “After having taught the students the conventional rules of each art, the professors shall endeavour to develop in them a taste for a national art, that which should become the expression of the modern civilized Egyptian. This will be thanks to what is available to them through the remarkable examples they see of Egyptian monuments and relics and of the Golden Age of Arab art.”8Fatenn Mostafa Kanafani, Modern Art in Egypt: Identity and Independence, 1850–1936 (I. B. Tauris, Bloomsbury, 2020), 43; citation of Muzakarat,’ in Ramadan, Dina A. “The Aesthetics of the Modern: Art, Education, and Taste in Egypt 1903-1952.” The Aesthetics of the Modern: Art, Education, and Taste in Egypt 1903-1952, Columbia University , Columbia University, 2013: 91.

Egyptian modernists responded to this prompt by representing the rural Egyptian, a figure that could potentially unite a heterogeneous population seeking a national identity.9There are also a number of artists who responded to this prompt by drawing on Pharaonic tropes and figures, as Ashamallah does as well. Both the rural figure and the Pharaonic legacy were important in the formation of a national artistic identity for the Egyptian modernists, though here I will focus more on the former. For more references on Pharaonic tropes in modern Egyptian art see Kanafani, Modern Art in Egypt; 170-171; 177-182; 201-207; 239-248. As did the artists Mahmoud Saïd (1897–1964), Seif Wanly (1906–1979) and his brother Adham Wanly (1908–1959), Ragheb Ayad (1892–1982), Mahmoud Naghi (1888–1956), Hamed Owais (1919–2011), and Injy Aflatoun (1924–1989) before her, Ashamallah identified the rural condition as the ultimate, defining feature of Egyptian society. Like them, she occupied an insider-outsider position, portraying the peasant from close proximity though never fully occupying the role herself.

In the scramble to locate a static Egyptian national identity, images of peasants and the agricultural landscape they tilled—an unchanging constant across dynasties, kingdoms, and empires of rule—became a fixture in Egyptian artistic representation of the 20th century.10For more on the role of the peasant in Egyptian modernism, see Kanafani, Modern Art in Egypt; 89-171; and Arthur Debsi, “Imagery of the Egyptian Peasant, 1911–1956,” Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation website, May 30, 2022, https://dafbeirut.org/literature/imagery-egyptian-peasant-1911-1956. From Mahmoud Said’s 1938 portrait Fille à l’imprimé (Girl in a Printed Dress) to Mahmoud Mokhtar’s 1930 sculpture Au Bord du Nil (On the Banks of the Nile) or Injy Aflatoun’s 1963 L’Or Blanc (White Gold), the Egyptian modernists were obsessed with portraying the “ordinary Egyptian” in a rural setting. There is no doubt that this practice was highly influential in Evelyn Ashamallah’s work, with some of her early works portraying women as abstract, organic figures that resemble Mokhtarian sculptures.

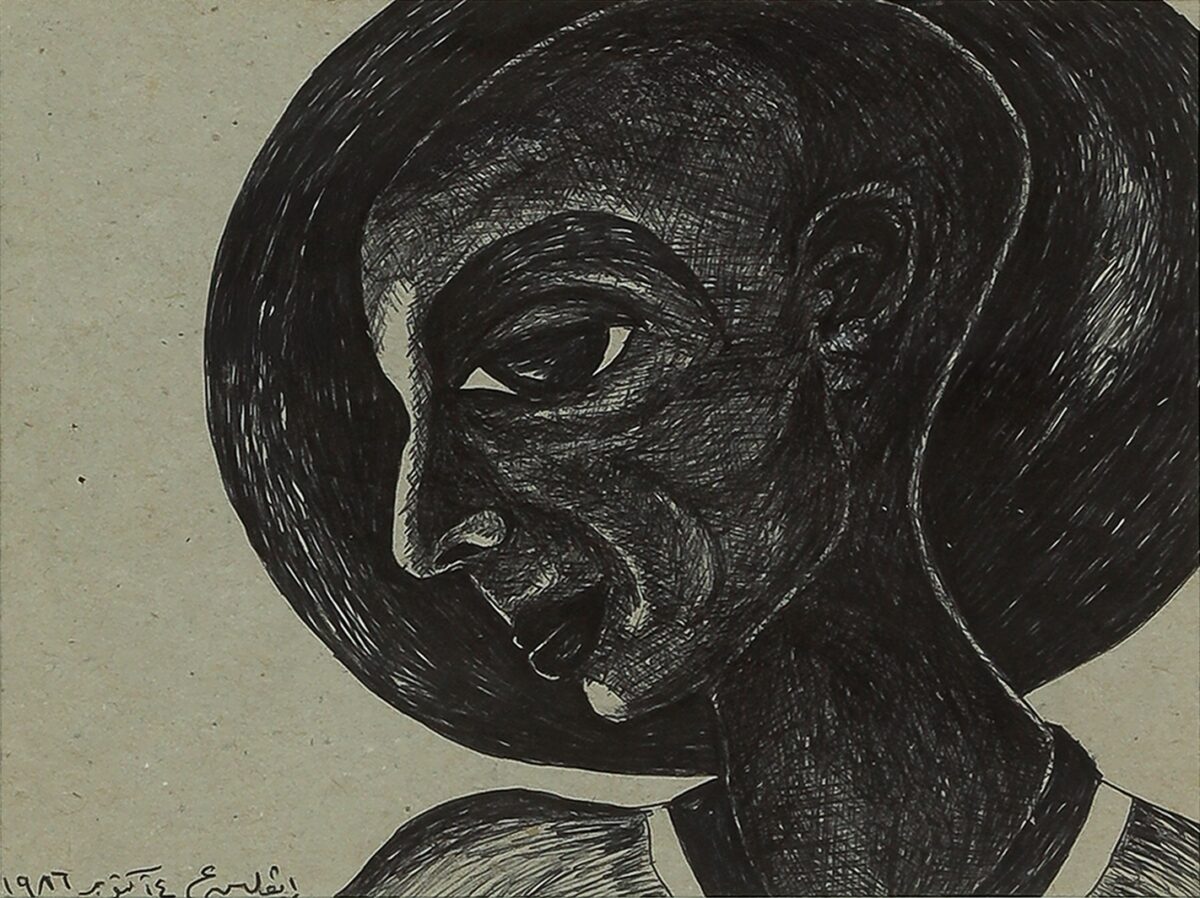

In 1986, Ashamallah borrowed from the tropes of peasant representation (for example, the jagged portraiture of Hamed Oweais and the rural stereotypes of Ragheb Ayad) in Portrait or Analysis of the features of the Egyptian peasant, a profile sketch with a pseudo-Pharaonic phrenology (fig. 5). While this portrait borrows from Ashamallah’s antecedents, it also demonstrates the germination of some of her signature features: the almond-shaped hollow eyes and large skull. Over time, she further developed her own typologies of representation, departing from the rural depictions typical in the work of earlier Egyptian modernists.

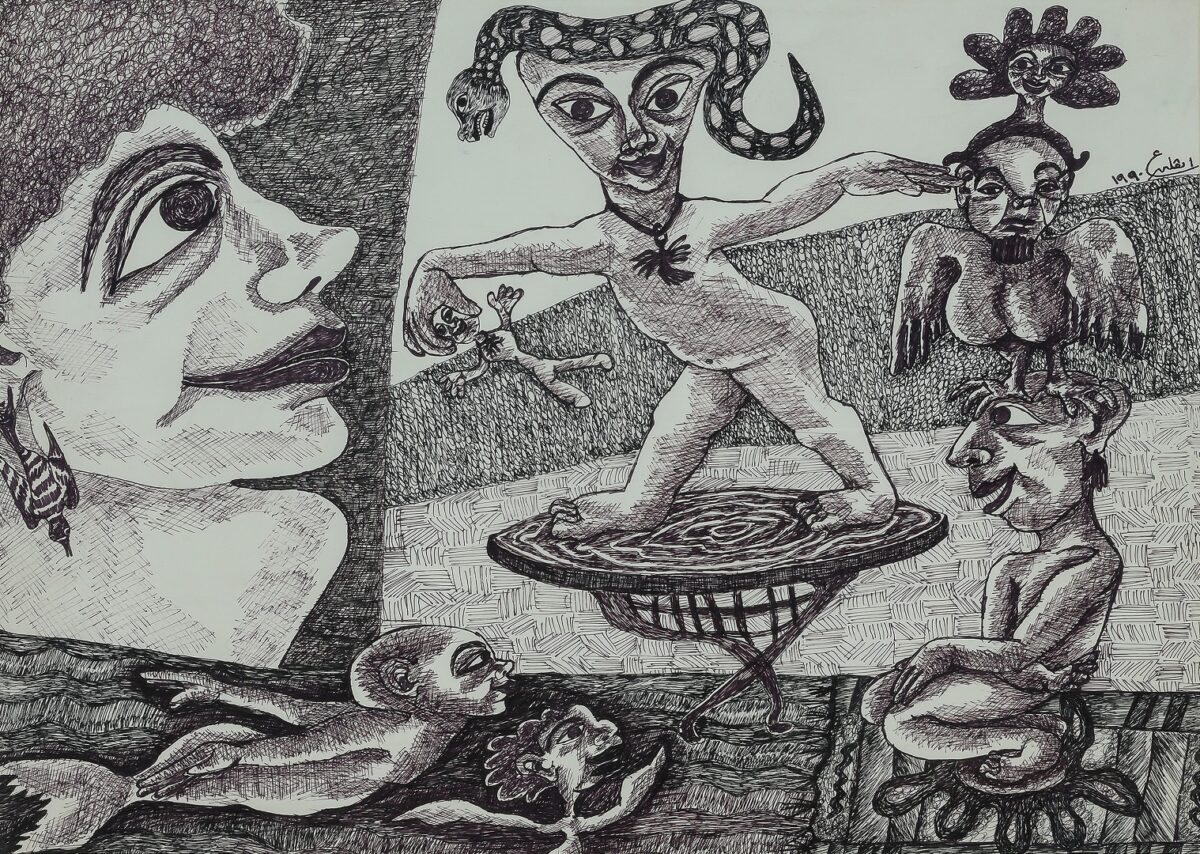

In her 1990 drawing The Peasants’ Hope, Ashamallah employs the signature stacked composition she used in her early Algerian landscapes to completely recast a tired and pernicious rural trope (fig. 6). In the left of the composition, a woman with curly hair and an earring in the form of a striped bird diving downward is rendered in closeup profile above an underworld inhabited by part-sea part-human creatures, who swim toward a twirling structure at the surface. Above it, a central figure is positioned in the typical Pharaonic stance, wherein the feet point in one direction, and the body and head face the viewer. This figure also wears bird-like jewelry as well as a snake on its head. On the right, the artist stacks three figures on top of each other to make one hybrid creature: a crouching man, a bird-woman, and a flower-child. Each figure in this totemic trio relates to a figment from Ashamallah’s memory. Free from the stereotypical tropes that were common in the work of her predecessors, Ashamallah portrays what she knows about Egyptian peasants. Perhaps her renderings are acts of subversion, but it is more likely that they are forms of fantastical futurity, pointing to a time when humans, animals, land, sea, and sky will have all collapsed into an incongruent harmony.

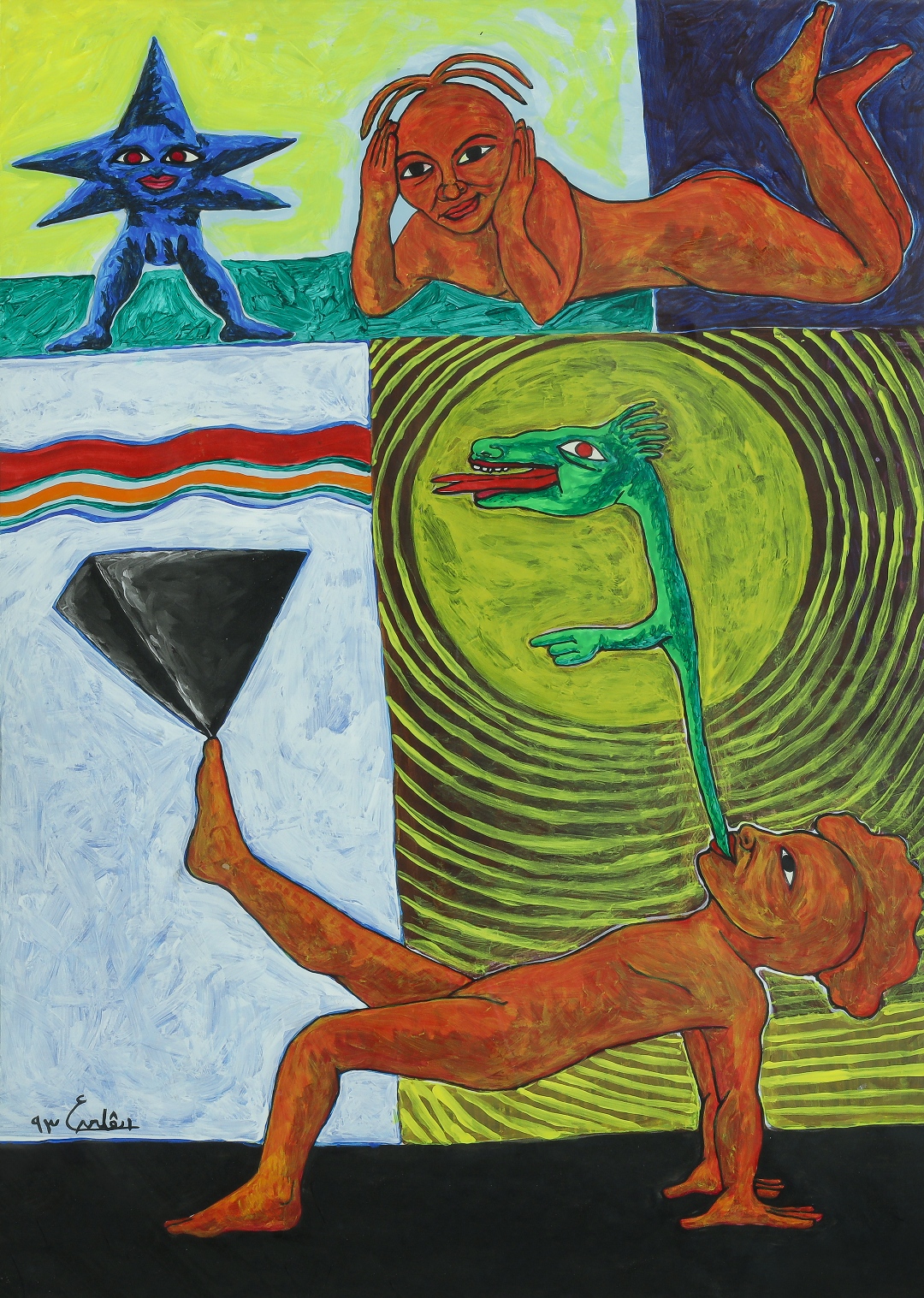

Throughout the 1990s into the early 2000s, Ashamallah dove further into the interspecies realms that had long populated her imagination. In the work from this period, we can begin to identify recurring motifs, including femininity, motherhood, and birth, which are conveyed by pregnant creatures or by characters contained in eggs, and womanhood in the form of reptilian beings with full breasts. These works almost always contain an unbridled articulation of humor and whimsy. As time progressed, Ashamallah depicted her figures with more limbs, tails, and fins, and she portrayed their encounters with even more levity. In her droll renderings, she would imagine conversations between different species that, as she has stated, “are not so easy to understand.” In her painting Balance (1993), we see her signature saturated colors deployed in the portrayal of four figures spilling over four quadrants of a composition (fig. 7). A turnip-headed red boy lies on his stomach and swings his feet next to a blue star creature with red lips, who smiles directly at the viewer. On the bottom of the composition, another red boy balances a reptilian figure in his mouth and an upside-down pyramid on his foot. As in Ashamallah’s other works, the composition is split and stacked, with each section containing a creature floating in its own respective world, yet brought into conversation with the other creatures in their whimsical portrayal.

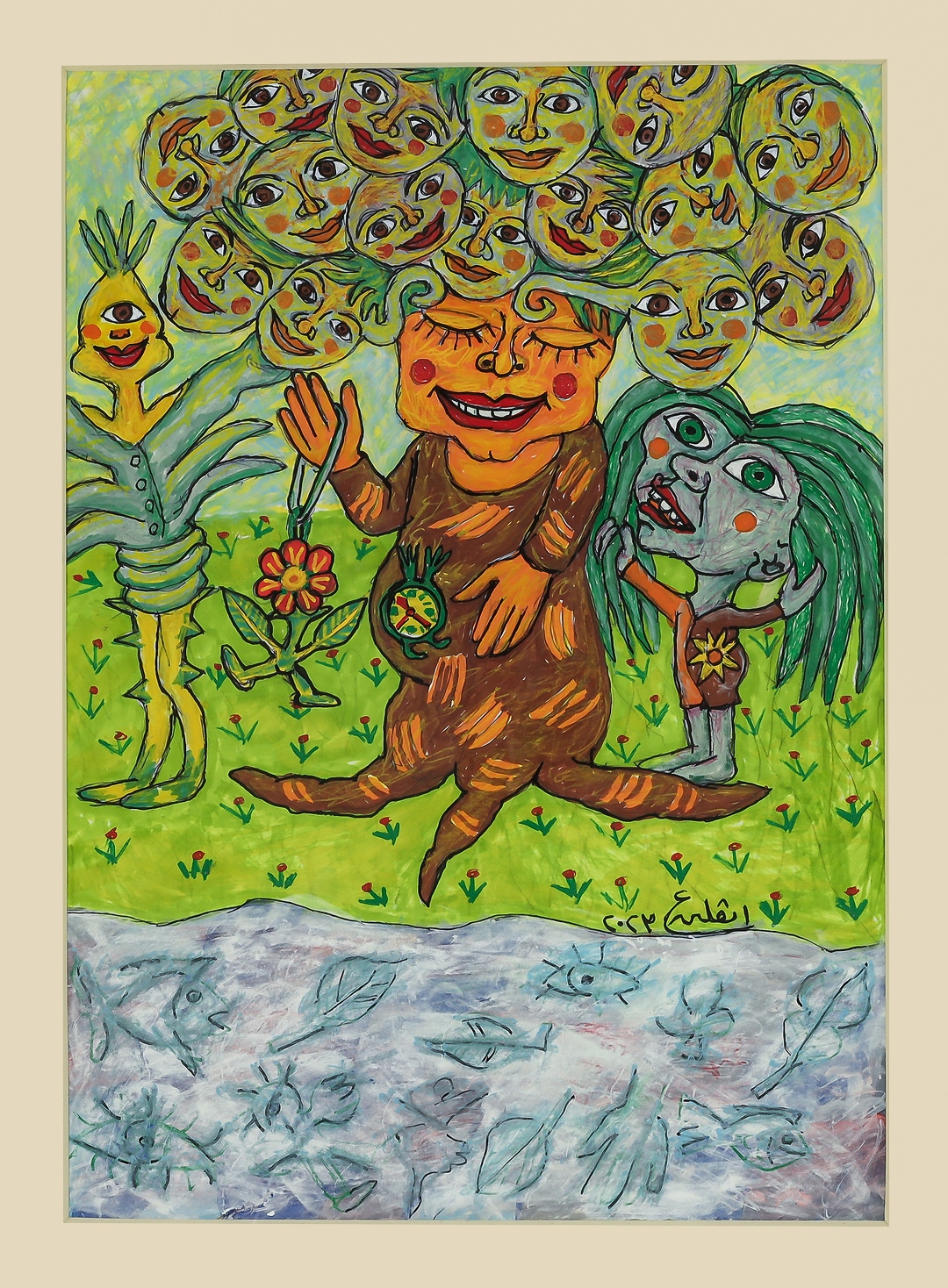

In the fall of 2024, Ashamallah’s largest retrospective opened at Azad Art Gallery in Cairo’s Zamalek neighborhood. Titled The Harvest of a Lifetime, this exhibition was organized by decade, demonstrating Ashamallah’s evolution as an artist and offering unfettered access to her phantasmagorical world.11The Harvest of a Lifetime, Azad Art Gallery, Cairo, September 15–27, 2024. In some ways, Ashamallah’s ongoing legacy fits squarely into an art historical evolution of Egyptian modernism that draws key articulations from the rural. However, her representations offer something much more alluring than those of her predecessors. In reading her paintings and drawings alongside her writings, her exile, her political engagement, and then her disengagement, it becomes clear that her imagination is her antidote to the injustices that she has borne witness to throughout her life. She knows that this world-building is not entirely her own creation, as it follows the folktales and customs that surrounded her as a child. Now, looking back on a life laden with the contradictions, affiliations, and disaffiliations not uncommon to those navigating the rubble of the 20th century, Ashamallah consciously returns to the land, still, still invigorated by the potential of its promise (fig 8).

- 1Unless otherwise indicated, all personal accounts from Evelyn Ashamallah were gathered by the author during discussions with the artist in the fall and winter of 2024–25.

- 2According to Rabea Eghrabiah, “Meaning ‘catastrophe’ in Arabic, the term ‘al-Nakba’ (النكبة) is often used—as a proper noun, with a definite article—to refer to the ruinous establishment of Israel in Palestine. A chronicle of partition, conquest, and ethnic cleansing that forcibly displaced more than 750,000 Palestinians from their ancestral homes and depopulated hundreds of Palestinian villages between late 1947 and early 1949.” Eghrabiah, “Toward Nakba as a Legal Concept,” Columbia Law Review 124, no. 4 (2024), 889, https://columbialawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/May-2024-1-Eghbariah.pdf. See also Lila Abu-Lughod and Ahmad H. Sa’di, “Introduction: The Claims of Memory,” in Nakba: Palestine, 1948, and the Claims of Memory, ed. Ahmad H. Sa’di and Lila Abu-Lughod (Columbia University Press, 2007), 1–24; and “About the Nakba,” in “The Question of Palestine,” United Nations website, https://www.un.org/unispal/about-the-nakba/.

- 3For more on the role of the mantis within the Surrealist tradition, see Ruth Markus, “Surrealism’s Praying Mantis and Castrating Woman,” Woman’s Art Journal 21, no. 1 (2000): 33, https://doi.org/10.2307/1358868.

- 4The Tahrir uprising on January 25, 2011, included a massive public demonstration demanding democracy and an end to President Hosni Mubarak’s 30-year rule that evolved into an 18-day occupation of the square, with protesters facing tear gas and violence from security forces. It culminated on February 11, 2011, when Mubarak resigned, handing power to the military. For more on this subject, including a historicization of protest movements in Egypt leading up to January 2011, see Bahgat Korany and Rabab El-Mahdi, eds., Arab Spring in Egypt: Revolution and Beyond (American University in Cairo Press, 2012).

- 5Evelyn Ashamallah, in discussion with the author, October 29, 2024.

- 6Translated from the Arabic غيطان الفلاحين

- 7Mohammed Khadda, “Elements for a New Art” [1964], in Modern Art in the Arab World: Primary Documents, ed. Anneka Lenssen, Sarah A. Rogers, and Nada M. Shabout (The Museum of Modern Art, 2018), 232.

- 8Fatenn Mostafa Kanafani, Modern Art in Egypt: Identity and Independence, 1850–1936 (I. B. Tauris, Bloomsbury, 2020), 43; citation of Muzakarat,’ in Ramadan, Dina A. “The Aesthetics of the Modern: Art, Education, and Taste in Egypt 1903-1952.” The Aesthetics of the Modern: Art, Education, and Taste in Egypt 1903-1952, Columbia University , Columbia University, 2013: 91.

- 9There are also a number of artists who responded to this prompt by drawing on Pharaonic tropes and figures, as Ashamallah does as well. Both the rural figure and the Pharaonic legacy were important in the formation of a national artistic identity for the Egyptian modernists, though here I will focus more on the former. For more references on Pharaonic tropes in modern Egyptian art see Kanafani, Modern Art in Egypt; 170-171; 177-182; 201-207; 239-248.

- 10For more on the role of the peasant in Egyptian modernism, see Kanafani, Modern Art in Egypt; 89-171; and Arthur Debsi, “Imagery of the Egyptian Peasant, 1911–1956,” Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation website, May 30, 2022, https://dafbeirut.org/literature/imagery-egyptian-peasant-1911-1956.

- 11The Harvest of a Lifetime, Azad Art Gallery, Cairo, September 15–27, 2024.