Series Introduction

This series of three articles presents a selection of the performative practices in Armenian art in the late-Soviet and post-Soviet periods, practices that would herald the separation of nonofficial artists from the official Soviet cultural discourses and practices, and subsequently, in the 1990s, mark the institutionalization of nonofficial or semiofficial art as “contemporary art.” These practices were often not only symptomatic but also, at times, prognostic of broader sociopolitical developments in late-Soviet and post-Soviet Armenia.

The twenty years covered here—from 1987 to 2008—are conditionally demarcated as the period of transition from the late-Soviet to the post-Soviet condition (with an ideological implication of being a transition to liberal democracy)1In his book Transition in Post-Soviet Art, art historian Octavian Esanu refers to contemporary art in the post-Soviet sphere as the art of the post-socialist transition, with “transition” understood as the triumphalist shift to market capitalism and liberal democracy that is assumed to be the natural course of history. See Esanu, Transition in Post-Soviet Art: The Collective Actions Before and After 1989 (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2013). and ultimately to a marriage of neoliberalism and nationalism in the 2000s. The political and cultural discourses of glasnost in the 1980s would herald the onset in the 1990s of market capitalism, with its “inhuman face” (in contrast to “socialism with a human face”)2This slogan was used by reformist communists in Czechoslovakia in 1968 and was later adapted in the USSR during perestroika.combined with the construction of the liberal democratic nation-state on the ruins of Soviet modernity. However, in the later 1990s and throughout the 2000s, market capitalism and liberal democracy were decoupled, and late capitalism’s Armenian variant triumphed alongside the ideology of neoliberalism under the protective umbrella of political authoritarianism. This periodization, however, is not solely guided by political events. It also follows the internal development of performative practices as they unfolded within the complex contradictions and tensions of the late-Soviet and post-Soviet conditions. If in the late 1980s and throughout most of the 1990s, artists participated in the construction of a new state and in its cultural discourses through collective actions and interventions in the public sphere, in 1999–2008, with a few exceptions, they conducted solo performances and actions. If in the first instance, artist collectives laid claim to social participation and engagement, in the second, individual artists explored the embodied, sexed, damaged, and annihilated subject violated by political and social forces of control and repression.

As part of the explosion of political and cultural practices that challenged the officially sanctioned discourses, institutions, and narratives—and that encouraged a spirit of reformism licensed by Mikhail Gorbachev’s reformist agenda within the framework of perestroika and glasnost since the mid-1980s—performative gestures executed in the context of multimedia and multi-genre exhibitions therein formed within and in response to perestroika’s imperative of reforming official institutions from within.3Harutyunyan, Political Aesthetics of the Armenian Avant-Garde.Here, performative acts and actions came to signify unmediated communication between the artist and their public, an aspiration for the late-Soviet Armenian avant-garde artists. In their very origin, performative acts, as discreet as they may seem—whether Happenings and art actions in the late 1980s and 1990s or performance and video art in the late 1990s and 2000s—shared one fundamental characteristic: they were undertaken in opposition and resistance to dominant political and cultural discourses and narratives, even in moments when they adopted an overtly affirmative tone.4Often the rhetoric of resistance and transgression has been a retrospective construction by the artists themselves when remembering their earlier practices from a historical distance. See Angela Harutyunyan, “Veraimastavorelov hanrayin volorty: Sahmanadrakan petutyunn u Akt xmbi hastatoghakan qaghaqakan geghagitutyuny,” Hetq,September 23, 2010, https://hetq.am/hy/article/305930,and David Kareyan’s response, “Akt xmbi araspely,” Hetq, September 27, 2010, https://hetq.am/hy/article/30594. The performative gesture became a necessary means for pointing toward and critically challenging the boundaries of institutions, disciplines, discourses, established cultural narratives, and dominant aesthetic regimes at a time when the relationship between the center and the margins of culture was shifting and unstable.Attached to the advent and institutionalization of semiofficial and nonofficial art in the late Soviet period (which in the 1990s came to be referred to as “contemporary art”)5For a discussion of the later Soviet dissident ideologies that paved the way for contemporary art’s anti-Soviet program, see Angela Harutyunyan, “Toward a Historical Understanding of post-Soviet Presentism,” chap. 1 in Contemporary Art and Capitalist Modernization: A Transregional Perspective, ed. Octavian Esanu (New York: Routledge, 2021). and part of the broader context of overcoming the medium-bound imperatives of officially sanctioned art, performative practices carried with them the dilemmas and ambiguities characterizing late-Soviet and post-Soviet avant-gardes: the desire to remain marginal and resistant (even if political conditions were at times ripe for occupying “the center”), self-institutionalizing, and yet—espousing a quasi-anarchic anti-institutional rhetoric—adopting grand and absolute gestures that aimed to constitute their own artistic context as more real than reality itself and ultimately being formed by the negation of the Soviet historical experience.

Part I

1980s: Resurrected Ghosts, Underground Heroes, and Saintly Saviors

The show “Happening,” which opened in Yerevan in 1982 and was curated by V. Tovmassyan, was an important show. Vigen Tadevossyan . . . presented a huge balloon that was constantly being filled with air. There was a wonderful poet named Belamuki. But focus was on two actors who, in a very strange way, resembled Salvador Dali and Picasso.

“To be honest, it was neither a happening nor a performance, but theatre directed by the sculptor Vardan Tovmassyan. I was not invited to the above-mentioned exhibition, and a month later decided to make a performance entitled “Exit to the city.” . . . For about an hour we were screaming texts edited from politically oriented newspapers and art magazines. The speech of Henry Igityan (the first and “irreplaceable” director of the Museum of Modern Art since 1972) that followed the performance was very typical of the times: “Our people do not need your experiments” (we performed both “Happening” and “Exit to the City” in his museum space). It meant that neither my friends nor I could have exhibitions there any more, not to mention at the Artists’ Union. We had to exhibit on the streets, at the conservatory, and the education worker’s house.”6Arman Grigoryan, “Informed but Scared: The ‘3rd Floor” Movement, Parajanov, Beuys and Other Institutions,” in Adieu Parajanov: Contemporary Art from Armenia, ed. Hedwig Saxenhuber and George Schöllhammer (Vienna: Springerin, 2003), 13–15, https://www.springerin.at/static/pdf/adieu_parajanov.pdf—Arman Grigoryan

This quote from artist Arman Grigoryan’s recollection of the early to mid-1980s art scene in Yerevan is one of the very few published statements on performative artistic gestures in Armenia at the time. But Grigoryan’s testimony is more than symptomatic. Indeed, it not only reveals the discontent that he and his peers experienced with nonofficial artists of the 1970s generation, it also places them antagonistically in relation to the “officially oppositional” Museum of Modern Art and its founding director.7Vardan Azatyan, “Disintegrating Progress: Bolshevism, National Modernism, and the Emergence of Contemporary Art in Armenia,” ARTMargins 1, no. 1 (February 2012): 62–87, https://doi.org/10.1162/ARTM_a_00004.The museum was the first of its kind in the USSR. It presented works by the 1960–70s generation of artists who entered the scene because of the Thaw, Nikita Khrushchev’s liberalization of culture. In their work, they reflected on national and ethnic themes with modernist form and positioned themselves as oppositional to orthodox Soviet culture, although the very foundation of the Museum was licensed by the Soviet state. Given this anti-institutional ethos, one would expect the Museum to be a natural ally of the younger generation of rebellious artists. However, acting from a position of defense of high modernism and its national spirit, the Museum responded negatively. The anti-institutional ethos—even when enacted from within an institution, as was already the case with the Museum of Modern Art in Yerevan—was to characterize the first large artistic/cultural movement of nonofficial artists in Armenia: the 3rd Floor. The assumption that truly free art has the power to break away from institutional boundaries and conventions was to become formative for contemporary art in Armenia and serve as a key signifier of the resistance and subversion attached to performative practices. These practices were often seen as a means of revealing the truth that the deceptive facade of official narratives and institutions concealed. As the figure of truth, the performative gesture occupies a structurally marginal and, at times, subterranean position vis-à-vis the official institutions.

In 1987 young art critic Nazareth Karoyan—as if echoing Grigoryan’s retrospectively expressed discontent with the Museum of Modern Art in Yerevan—first discovered and then meticulously categorized the garbage accumulated on the roof of the Museum. The pile of trash was documented in an inventory that Karoyan presented the same year at the Union of Artists’ official meeting, to the distress of many of those present. It is interesting that garbage, as a signifier of contradictions hidden behind the beautiful facade of official cultural politics, was not merely revealed but also categorized and itemized. This conceptual gesture was among the triggers for the 3rd Floor’s first exhibition, held that same year, and marked the movement’s mission, which was to reform cultural institutions from within and resist official culture from its very margins.

In the same year as Karoyan’s “garbage action,” a group of artists embarked upon the reformation of the Union of Artists of Armenia. This first event was more of a festival than a coherent exhibition, and it took place in the conference hall located on the third floor of the Union, a space not designated for exhibitions. It was the location of the organization’s first convention that gave the movement its name: “the 3rd Floor.” The 3rd Floor came into being in 1987 when several young artists were invited to be part of the youth division of the Union.

Ideologically, the movement presented a mixture of romantic liberalism, nationalism, and libertarianism, with anarchist dreams of omnipotence and contradicting ideologies that often went hand in hand. Its members romanticized symbols of Western consumerism and subcultures to the degree that they had come to denote ideals of individual freedom and autonomy. The critique of Soviet culture through its opposite other—signs of capitalist consumer culture as inherently democratic—situates the 3rd Floor within the intellectual climate of the late-Soviet and socialist intelligentsia’s romantic alliance with liberal democracy. In the practices of those involved in the 3rd Floor, these ideals were understood from an artistic perspective: the citizen’s freedom was equal to that of the artist’s “absolute and universal right to mix different artistic styles and images on the surface of the canvas.”8“Cucadrum e 3rd harky” [The 3rd Floor is showing], Arvest, no.11–12 (1992): 3–8.The Union’s seminal 1988 performance Hail to the Union of Artists from the Netherworld: The Official Art Has Died reenacted the opposition to the Soviet and its cultural policy on metaphorical terms.

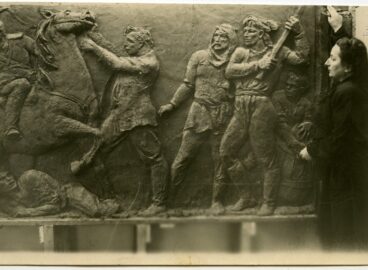

On December 12 several artists in the movement dressed as the resurrected dead and, like their heavy-metal heroes, strode into one of the Union of Artists’ conventional exhibitions and declared the death of official art. In this Happening, recorded under two different titles—The Official Art Has Died and Hail to the Union of Artists from the Netherworld—they made their way silently through the exhibition hall, viewed traditional paintings hung on the walls of an art institution defending Soviet official orthodoxy, and recognizing the symptomatic significance of their action, took photographs of themselves in various groupings and positions before walking out. (fig. 3) This event crystalized the 3rd Floor’s belief in the incommensurability of art as a space for free creation and the institution ruled by the tyranny of banality: if art is the collectively constructed dream of underground heroes, the institution is the counterimage of the conventional domain of a properly dead and officially sanctioned reality.9Angela Harutyunyan, Political Aesthetics of the Armenian Avant-Garde, 59.

Within the framework of perestroika’s belief in change from within, the 3rd Floor oscillated on a thin and delicate line between official recognition and rejection, occupying both the cultural mainstream and its vanguard margins. The official discourse of the pre-perestroika period of stagnation, identified with the Soviet experience as such, returned in the practices of the 3rd Floor’s members as a trauma never able to be articulated but rather transformed through the recurring return of various invented and real personages. These personages were born from the anti-Soviet realm. Sometimes they occupied the margins of official discourses, styles, forms, and techniques; at other times, they hid underground from the watchful eyes of the Soviet collective consciousness. The “Soviet” recurred in the haunted figures of ghosts and “authoritarian personages,” such as a character found in the works of Grigor Mikaelyan (known as Kiki), who was, at that time, part of the 3rd Floor. Kiki constructed and consistently pursued the “revelation” of Bobo, a disembodied fictional character with no particular shape or form, whose name is commonly invoked to scare children. In Kiki’s series of abstract paintings, which materialize through performative gestures, Bobo is the secret service agent, the KGB officer, the immaterial eye that controls: he is the scarecrow for the dissident intelligentsia. The figure of Bobo had to be constantly reconstituted, constantly in process, never fully materialized. (The first Bobos appeared in the mid-1980s, and they continue to appear today.) This figure would be indexed through a performative action enacted on a canvas spread out on the floor around which the artist circled in mad movements as they threw paint in scribbly brushstrokes (or rather “broomstrokes,” as Kiki would always use a broom). The canvas itself became a site of exorcism of the official and ideological. This character’s formal features include two circles created through the expressive gestural application of paint and sometimes enclosed in a triangle, while its repetitive reconstitution reveals the compulsively repetitive structure of trauma—a repetition that paradoxically recurs as a unique event each time it is reproduced. The canvas appears as a space of psychic discharge upon which the repressed returns.10Angela Harutyunyan, Political Aesthetics of the Armenian Avant-Garde, 57–59.

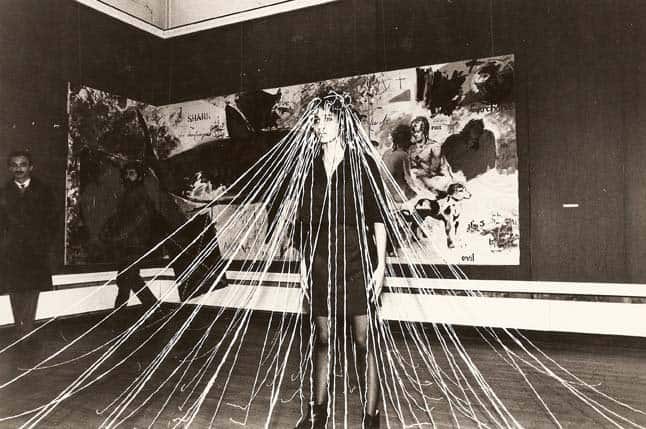

In the framework of the 3rd Floor’s exhibitions, artist Ashot Ashot executed several performances that made metaphysical claims of transcendence through the overcoming of “facts.” For this, Ashot Ashot adopted a self-designated strategy called afaktum, which comprised deliberate and methodic reduction of matter and speech to their basic elements, pointing toward “permanent art.” A photograph of his performance A Structure of Communication for the 1989 exhibition 666 shows a woman standing in the middle of the action with threads diagonally stretched from her head to the ground and forming a web around her. (fig. 5) Here, communication is revealed as a cultural imperative of a supposedly closed world opening to the outside, but as soon as it is revealed, it is demolished: the threads are subsequently unthreaded and destroyed.

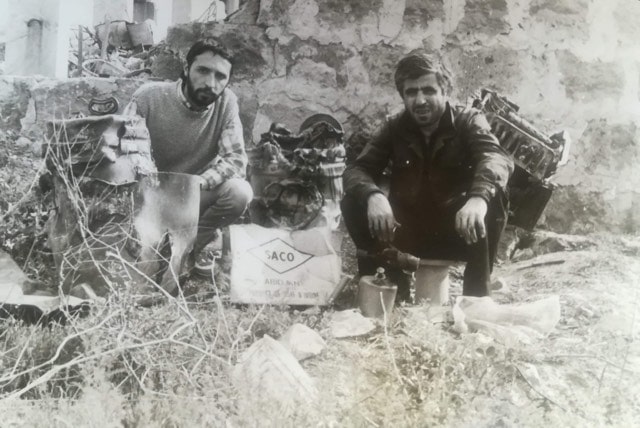

Another underground hero of the netherworld Sev (Herik Khachatryan) used performative actions to produce objects from scrap metal. His adopted persona was itself performative, involving his signature black clothing, a color reaffirmed in his artistic name (sev in Armenian means “black”).11According to Sev, he chose the name because of his attraction to Malevich’s Black Square (1913) and because of the practical nature of the color in terms of clothing: for a young bachelor, black clothes were convenient since they do not show dirt as easily. Sev, in discussion with the author, April 8, 2022.As early as 1985 (since his first encounter with Kiki), Sev had been visiting junkyards, collecting scrap metal, and welding it in front of audiences as objets, a practice that is ongoing. A photograph from 1987 records one such expedition to the Yerevan Thermal Power Plant with photographer Aram Udinyan. (fig. 6) In this image, both protagonists are squatting next to materials they have gathered. One can only imagine Sev’s “sinister” visage, dressed all in black, marching with a fire torch and manipulating metal in front of bewildered audiences in the late-Soviet years. Sev’s work was directly inspired by postwar Neo-Dada and Nouveau Realism, which he encountered for the first time through catalogues and slides introduced by art critic Nazareth Karoyan.12Sev, in discussion with the author.In a 1989 action, the artist paid homage to his idol of Nouveau Realism César (César Baldaccini; French, 1921–1998) during the 3rd Floor’s visit to Paris for the opening of their exhibition. The artist executed a reverse summersault in front of one César’s assemblages. (fig. 7) For Sev, artists of the historical avant-garde and neo-avant-garde, such as Kazimir Malevich (Russian, born Ukraine, 1878–1935), César, and Alberto Burri (Italian, 1915–1995) were his guides and inspiration toward a countercultural understanding of art as a sphere of freedom.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s the imperative formulated by the late-Soviet anti-Soviet artistic avant-garde in Armenia was the revelation of the authentic yet subterranean layers of reality as truth that had been distorted and falsified behind the ideological facade of official lies. The allegorical personifications of this subterranean truth were various netherworld dwellers, as in the case of the 3rd Floor’s 1988 Happening, or antiheroes whose painterly materialization invoked deep-seated scopophobia (Bobo’s main feature are the two empty circles that gaze back from their void without forming an eye—a “location” of the scopic drive that circles around the organ but never dwells within it, as per Lacan’s formulation of the gaze)13See Jacques Lacan, “The Split between the Eye and the Gaze” (1964), in The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, trans. Alan Sheridan, ed. Jacques-Alain Miller (New York: W. W. Norton, 1978), 67–78. and the surpassing of the empirical and factual in search of a quasi-mystical pure reality (as in the work of Ashot Ashot). But paradoxically, these anxieties of visibility were not revealed through disappearance and immaterialization but instead through loud gestures and actions of excess and plentitude that were positioned as constituting a counter-sphere to the official and the ideological. Ultimately, the 3rd Floor was striving for cultural and social visibility.

Aesthetically, the artists associated with the movement engaged with painting in an “expanded field” in order to exceed it from within, through the body and temporality: artists of the Happening walked through an exhibition of paintings with their faces painted, Bobo was invoked in paintings, and Ashot-Ashot “overcame” paint by spilling it over the model’s body. Painting here was both affirmed and surpassed through its multimedia expansion, and this dynamic of affirming a traditional medium while exceeding its specificity and, at times, negating it altogether rhymes with the structural positioning of these gestures from within the official discourse and in resistance to it. In other words, these performative gestures were articulated from within the margins of the officially sanctioned glasnost policy as its avant-garde. Retrospectively, however, the 3rd Floor artists often situated their exhibitions as a resistant and anti-institutional subcultural response to what they perceived as the violence of the official culture that hindered freedom and creativity. With the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 and Armenia’s independence, this understanding of avant-garde art as a mode of subcultural resistance to the dominant culture entered a certain crisis. As the Soviet world was disappearing through fast-paced privatization, financial collapse, de-modernization of urban spaces, and socially induced historical amnesia of the recent past, to the late-Soviet avant-gardists, the 1990s promised a reconciliation between art (imagined as a realm of free creation) and dominant culture (understood as a regressive and repressive mechanism of conformity).

Editors’ note: Read Part II of this series here, and Part III here.

Author’s note: The research for this three-part article was commissioned by ARé Cultural Foundation in 2022. Some parts are informed by earlier research conducted for my monograph. See Angela Harutyunyan, Political Aesthetics of the Armenian Avant-Garde: The Journey of the “Painterly Real,” 1987–2004 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017)

- 1In his book Transition in Post-Soviet Art, art historian Octavian Esanu refers to contemporary art in the post-Soviet sphere as the art of the post-socialist transition, with “transition” understood as the triumphalist shift to market capitalism and liberal democracy that is assumed to be the natural course of history. See Esanu, Transition in Post-Soviet Art: The Collective Actions Before and After 1989 (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2013).

- 2This slogan was used by reformist communists in Czechoslovakia in 1968 and was later adapted in the USSR during perestroika.

- 3Harutyunyan, Political Aesthetics of the Armenian Avant-Garde.

- 4Often the rhetoric of resistance and transgression has been a retrospective construction by the artists themselves when remembering their earlier practices from a historical distance. See Angela Harutyunyan, “Veraimastavorelov hanrayin volorty: Sahmanadrakan petutyunn u Akt xmbi hastatoghakan qaghaqakan geghagitutyuny,” Hetq,September 23, 2010, https://hetq.am/hy/article/305930,and David Kareyan’s response, “Akt xmbi araspely,” Hetq, September 27, 2010, https://hetq.am/hy/article/30594.

- 5For a discussion of the later Soviet dissident ideologies that paved the way for contemporary art’s anti-Soviet program, see Angela Harutyunyan, “Toward a Historical Understanding of post-Soviet Presentism,” chap. 1 in Contemporary Art and Capitalist Modernization: A Transregional Perspective, ed. Octavian Esanu (New York: Routledge, 2021).

- 6Arman Grigoryan, “Informed but Scared: The ‘3rd Floor” Movement, Parajanov, Beuys and Other Institutions,” in Adieu Parajanov: Contemporary Art from Armenia, ed. Hedwig Saxenhuber and George Schöllhammer (Vienna: Springerin, 2003), 13–15, https://www.springerin.at/static/pdf/adieu_parajanov.pdf

- 7Vardan Azatyan, “Disintegrating Progress: Bolshevism, National Modernism, and the Emergence of Contemporary Art in Armenia,” ARTMargins 1, no. 1 (February 2012): 62–87, https://doi.org/10.1162/ARTM_a_00004.

- 8“Cucadrum e 3rd harky” [The 3rd Floor is showing], Arvest, no.11–12 (1992): 3–8.

- 9Angela Harutyunyan, Political Aesthetics of the Armenian Avant-Garde, 59.

- 10Angela Harutyunyan, Political Aesthetics of the Armenian Avant-Garde, 57–59.

- 11According to Sev, he chose the name because of his attraction to Malevich’s Black Square (1913) and because of the practical nature of the color in terms of clothing: for a young bachelor, black clothes were convenient since they do not show dirt as easily. Sev, in discussion with the author, April 8, 2022.

- 12Sev, in discussion with the author.

- 13See Jacques Lacan, “The Split between the Eye and the Gaze” (1964), in The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, trans. Alan Sheridan, ed. Jacques-Alain Miller (New York: W. W. Norton, 1978), 67–78.