Although principally a political gathering, the Bandung Conference (or Asian-African Conference) of 1955 also hosted visual spectacles, including an architectural vista whose key buildings comprised the conference’s hotels and meeting venues, all renovated specifically for the occasion. The weeklong event, which took place April 18–24, 1955, brought together representatives from twenty-nine newly or soon-to-be independent Asian and African nation-states in Bandung, Indonesia, to negotiate economic cooperation and cultural collaboration across the Afro-Asian spheres. Art historian Y. L. Lucy Wang analyzes Bandung’s architecture and photographic record, revealing the ways in which the conference visually projected its aims of South-South solidarity by reconfiguring buildings laden with colonial history and bringing new meanings to architectural forms previously charged with historical associations.

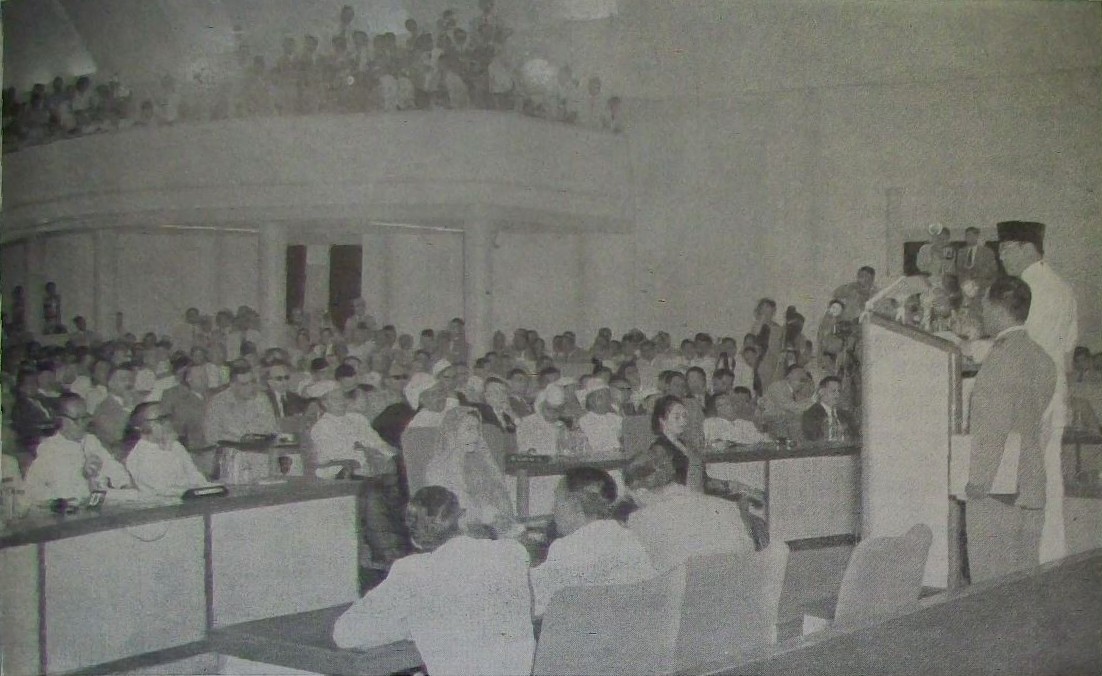

“Our nations and countries are colonies no more. Now we are free, sovereign, and independent. We are again masters in our own house.”1President Sukarno, “Let a New Asia and a New Africa Be Born!,” opening address, Bandung Conference, April 18, 1955, Bandung, Indonesia. See “Opening address given by Sukarno (Bandung, 18 April 1955),” CVCE.eu [Centre Virtuel de la Connaissance sur l’Europe], University of Luxembourg, https://www.cvce.eu/en/obj/opening_address_given_by_sukarno_bandung_18_april_1955-en-88d3f71c-c9f9-415a-b397-b27b8581a4f5.html. Dressed in a crisp military uniform and Muslim kopiah, President Sukarno of Indonesia delivered these words in his opening address at the 1955 Bandung Conference (or Asian-African Conference), a lectern dividing him from two floors of seated delegates and scores of international journalists crowding the room’s side aisles (fig. 1).

Although this evocation of “our own house” acts as a literary flourish that likens homeownership to the decolonization movements that swept the globe in the aftermath of World War II, it also contains a literal dimension. Sukarno’s “own house” was, in a sense, the physical venue where his words rang out. It was the same hall to which he made passing reference five times in the course of his speech and within which the Bandung Conference’s plenary sessions were held.2Ibid. Originally constructed in 1895 to house what was a primarily Dutch social club called the Sociëteit Concordia, the structure was rebuilt and enlarged in the ensuing decades, before being selected by Bandung Conference organizers as a key meeting venue (fig. 2). It was then quickly renovated, freshly painted, and renamed the Gedung Merdeka (Freedom Building). Recast in this way, it served to represent the homecoming of Sukarno’s postwar governmental forces, who, once again, were “masters in [their] own house”—a house to which they invited international delegates, to “discuss and deliberate upon matters of common concern” in the “first intercontinental conference of colored peoples in the history of mankind.”3Ibid. The Tricontinental Conference of 1966 is widely seen as a successor to the Bandung Conference, as it built upon Afro-Asian solidarity and emphasized diplomatic relations between Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Prior to the 1966 conference, the establishment of the Non-Aligned Movement, which held its first summit in Belgrade in September 1961, is also part of this lineage, although its participants were not uniformly nonwhite. This was the founding premise of the Bandung Conference, as Sukarno explained in his opening address at the Gedung Merdeka.

However, to characterize the aim of the conference as self-determined, anti-imperialist decolonization is to engage with the event as both a historical record and a mythos. Plenary sessions and closed-door meetings did indeed address political and economic interests, but recent scholarship has examined the ways in which on-the-ground realities diverged from stated goals. Robert Vitalis has scrutinized transcripts, direct outcomes, and the positions of different delegations, comparing them to first-hand reportage and public memory to expose various Bandung generalizations as mere “fables.”4Robert Vitalis, “The Midnight Ride of Kwame Nkrumah and Other Fables of Bandung (Ban-Doong),” Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development 4, no. 2 (Summer 2013): 261–88, https://doi.org/10.1353/hum.2013.0018. Robbie Shilliam has argued that self-determination, as pursued at the conference and by its participating delegations, followed colonial blueprints.5Robbie Shilliam, “Colonial Architecture or Relatable Hinterlands? Locke, Nandy, Fanon, and the Bandung Spirit,” Constellations 23, no. 3 (September 2016): 425–35, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8675.12163. In the realm of visual culture, Christopher J. Lee has analyzed the event’s intimate, seemingly informal photojournalistic street photography and how it actively participated in mythmaking.6Christopher J. Lee, “The Decolonising Camera: Street Photography and the Bandung Myth,” Kronos 46, no. 1 (November 2020): 195–220. Naoko Shimazu has framed the conference as a “theatrical performance” that “staged” the city of Bandung to be full of symbolic meaning legible to Western audiences learning about the event from its press coverage.7Naoko Shimazu, “Diplomacy as Theatre: Staging the Bandung Conference of 1955,” Modern Asian Studies 48, no. 1 (January 2014): 225–52.

This essay adds to the visual cultural discourse by foregrounding architecture—namely sites instrumental to the Bandung Conference, including the city’s airport, main thoroughfares, and two meeting venues—as material enablers of the event’s renown, from both near and far and as both fact and myth. In their glistening renovations and renamings, these architectural sites reveal the conference’s engagement with decolonization to be highly symbolic and intentionally so. Rather than burying the material remnants of Dutch East Indies colonial rule in the city of Bandung, conference organizers repurposed the spaces and structures of past regimes, creating new associations between architecture and its use and ownership while maintaining the visibility and legibility of this repurposing.

Conference as Stage and Curtain

If the Bandung Conference is to be viewed as a “stage” on which diplomacy was performed, to borrow Shimazu’s rich lens of analysis, then the city’s airport is the setting of Act One.8Ibid., 225. Events of public interest began upon arrival, not upon the start of plenary sessions days later. This much is clear, based on the formidable volume of press coverage of the airport itself—from photographs to interviews to speeches—and the fact that these media outputs are in line with the high visibility of international diplomatic outings and the publicity they engender.9Photographers such as Howard Sochurek (1924–1994) and Lisa Larsen (1925–1959), both employed at the time by LIFE magazine, alongside bevies of journalists, captured stills and video reels of various airport scenes—including the beaming figure of Prime Minister John Kotelawala of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) draped in a flower garland, and the stoic visage of Zhou Enlai, Premier of the People’s Republic of China, carrying a bouquet and walking alongside Indonesian Prime Minister Ali Sastroamidjojo. See “The LIFE Picture Collection,” Shutterstock, https://www.shutterstock.com/editorial/collections/the-life-picture-collection.

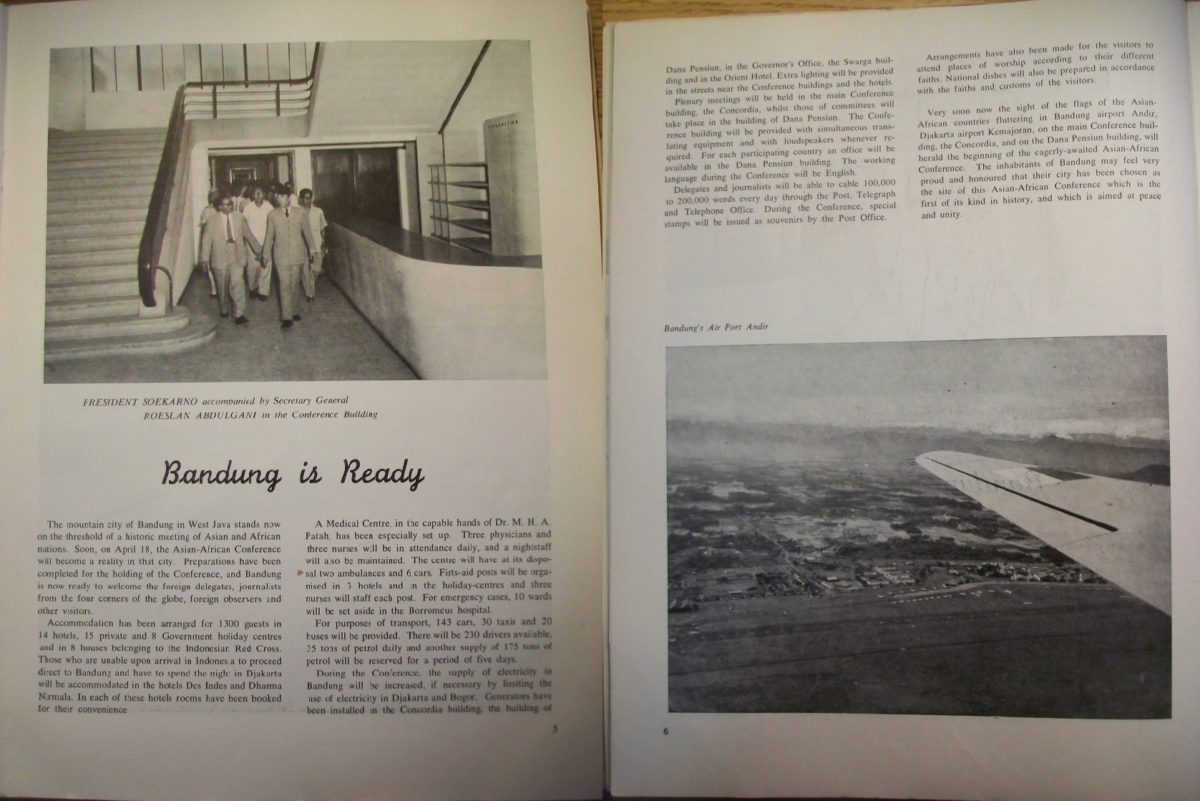

Elsewhere, however, this architectural setting stood as more than a dependable backdrop. One month prior to the opening of the Bandung Conference on April 18, 1955, and then daily throughout the event’s duration, the Indonesian government published the freely distributed, English-language Asian-African Conference Bulletin, which functioned equally as magazine, government-sanctioned reportage, and speech transcript. “Bandung is Ready,” the bulletin’s second issue declares. This bold, cursive-font headline and its accompanying descriptions of the preparations taking place citywide are visually bookended by two half-page images: an interior view of the Gedung Merdeka during an inspection tour led by President Sukarno and Secretary-General Ruslan Abdulgani, and “Bandung’s Air Port Andir” photographed from the air, its runway just visible below the plane’s left wing (fig. 3).10“Bandung is Ready,” Asian-African Conference Bulletin, no. 2 (April 1955): 6. As the last issue published before the conference opened, this volume also features a who’s who of national leaders via organizational charts and short biographies, as well as a summary of related press coverage. Since the publication is laid out like a photo book introducing readers to the conference’s most visible cast of characters, both human and architectural, it confers high recognizability to the Gedung Merdeka and Andir Airport (now the Husein Sastranegara International Airport), counting them among the list of prominent people and places associated with the conference.

These two photographs are noteworthy for their relative emptiness. The architecture of both locations, namely the Gedung Merdeka’s cruise liner–like Art Deco stairwell and Andir Airport’s runway, feature in the foreground, and despite the prominence of the figures in the former image, there exists a balance in visual composition between animate people and inanimate architecture. Thus, straight from the pages of the official bulletin-of-record of the Bandung Conference, one detects the intent to fashion architecture not simply as empty containers but rather as instrumental sites—or “stages”—signaling the city’s readiness to host international delegations.

A functioning airfield since decades past, when it served the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army Air Force, Andir Airport was renovated alongside other conference sites in the four months leading up to April 1955, although the decision was made to retain its name, a straightforward reference to the village of Andir. The most significant alterations targeted its diplomatic decorations, with airport crews installing the national flags of conference-attending delegations in a neat row along the runway (fig. 4).11“What It Was Like Watching the Opening Ceremony,” Asian-African Conference Bulletin, no. 3 (April 18, 1955): 14.

Across the city of Bandung, event organizers deployed flags in a similar fashion, draping architecture and public spaces in photo-op-appropriate symbols of the nation-state. These flagpole rows make a vivid appearance in The Color Curtain: A Report on the Bandung Conference (1956), a prominent first-person account by Black American writer Richard Wright:

“We drove past the conference building and saw the flags of the twenty-nine participating nations of Asia and Africa billowing lazily in a weak wind; already the streets were packed with crowds and their black and yellow and brown faces looked eagerly at each passing car. . . . Day in and day out these crowds would stand in this tropic sun, staring, listening, applauding; it was the first time in their downtrodden lives that they’d seen so many men of their color, race, and nationality arrayed in such aspects of power, their men keeping order, their Asia and their Africa in control of their destinies.”12Richard Wright, The Color Curtain: A Report on the Bandung Conference (Cleveland: World Pub. Co, 1956), 133–34.

The “color curtain” Wright evokes is a metaphor for Afro-Asian solidarity.13Ibid., 13. Based on shared postcolonial experiences and concerned “beyond left and right” political positions, this “color curtain” grouped the twenty-nine participants together as a cultural bloc. While Wright considered this unity to be an energizing potentiality as well as a personal imperative, he nevertheless acknowledges that a solidarity on the grounds of race and religion—“brown, black, and yellow men”—“was the kind of meeting that no anthropologist, no sociologist, no political scientist would ever have dreamed of staging; it was too simple, too elementary.”14Ibid., 13–14. Moreover, scholars like Brian Russell Roberts, Keith Foulcher, and Nina Kressner Cobb have critically studied Wright’s 1955 Indonesian travels alongside his optimistic narratives in The Color Curtain, proposing frameworks for engaging with Wright’s work as a deeply personal account reflective of his own political, racial, and national identities.15See Brian Russell Roberts and Keith Foulcher, eds., “Mochtar Lubis’s ‘A List of Indonesian Writers and Artists’ (1955)” and “Gelanggang’s ‘A Conversation with Richard Wright’ (1955),” chaps. 7 and 8 in Indonesian Notebook: A Sourcebook on Richard Wright and the Bandung Conference (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016); and Nina Kressner Cobb, “Richard Wright and the Third World,” in Critical Essays on Richard Wright, ed. Yoshinobu Hakutani (Boston: G. K. Hall, 1982), 228–39. In other words, historical scholarship has revealed The Color Curtain to be less a measured assessment of the Bandung Conference itself, in duration and legacy alike, and more an encapsulation of Wright’s worldview and hopes for the enduring spirit of the conference.

Perhaps, then, the rows of flags raised across Bandung could be considered their own form of color curtain. Placed at the Andir Airport, in various hotels, and both inside and outside of meeting venues, these lines of graphically bright textiles were fitting decorations for the conference and, simultaneously, intentionally oversimplified symbols of its participating agents. These physical curtains of bold color gave visual coherence to Wright’s hopeful if simplistic conception of the event’s twenty-nine delegations as a “color curtain” of solidarity.

Sites of the Conference: Renaming

Driving from Andir Airport to Bandung’s city center, as visiting delegations, members of the press, and Wright would have done, visitors encountered wide architectural vistas flanked on either side by motorcades and crowds of onlookers. American Unitarian minister Homer A. Jack, another governmentally unaffiliated visitor writing in the first person from Bandung, described the city as all “scrubbed and painted,” with its meeting venues “entirely rebuilt,” although the latter description is an exaggeration of the truth.16Homer A. Jack, Bandung: An On-the-Spot Description of the Asian-African Conference; Bandung, Indonesia; April, 1955 (Chicago: Toward Freedom, 1955), 5. Another American visitor and unofficial delegate to the conference was Adam Clayton Powell Jr. In reality, conference organizers arranged for renovations, not outright rebuilding, across the city in a four-month-long lead-up to April 1955.17Shimazu, “Diplomacy as Theatre,” 241.

Key renovations occurred at the Gedung Merdeka, the venue for the conference’s major speeches and plenary sessions; the Gedung Dwi Warna, a secondary meeting hall where the Economic, Cultural, and Heads of Delegations Committees held closed-door sessions; colonial-era villas, repurposed as residences for heads of delegations; fourteen hotels, including the Savoy Homann, a grand luxury resort designed in 1939 by Dutch East Indies-based architect Albert Aalbers; as well as public landmarks, such as Bandung’s central mosque, railway station, and aforementioned airport.18Ibid., 237.

With the exception of Andir Airport, the Gedung Dwi Warna, and individual villas, all of these structures are located in a compact zone in the city center, which the Joint Secretariat of the conference referred to as the “AAC zone,” short for “Asian-Africa Conference zone.”19Ibid., 237. Renovations to the area consisted of intensive cleaning, painting, street-vendor removal, and renamings. Jalan Alun Alun Barat (West Square Street) became Jalan Masjid Agung (Great Mosque Street), while the central thoroughfare cutting across the AAC zone, known formerly as Jalan Raya Timur (Great Eastern Street), became Jalan Asia Afrika. Under Dutch rule, Jalan Asia Afrika was home to governmental buildings, hotels, and other upscale structures, and if plans to move the colonial capital from Batavia to Bandung had materialized before World War II, this wide avenue would have served as the equivalent of the Champs-Élysées for Bandung, dubbed the “Paris of Java.” The Gedung Dwi Warna, just like the Gedung Merdeka, also underwent a reinvention by way of repurposing and renaming. Formerly a colonial governmental office for administering pension funds, the structure also served as a military headquarters during the Japanese occupation. Its new 1955 identity as the Gedung Dwi Warna (Two-Color Building) references Indonesia’s red-and-white post-independence national flag, in keeping with the liberatory theme of conference-related renamings (fig. 5).

According to news coverage and the reminiscence of Secretary-General Ruslan Abdulgani, President Sukarno took an active and personal interest in Bandung’s pre-conference architectural preparations. Beyond the fanfare and photojournalistic coverage of him inaugurating renamed sites, he also personally selected conference venues and made decisions regarding the “inspiring” design directions their renovations should take.20Ruslan Abdulgani and Molly Bondan, The Bandung Connection: The Asia-Africa Conference in Bandung in 1955 (Singapore: Gunung Agung, 1981), 68. Sukarno’s time in Bandung far predated the conference and can be traced back to his adolescence. In 1921 he enrolled at the Technische Hoogeschool te Bandoeng (now Bandung Institute of Technology) to study architecture and civil engineering and then, after graduation, he established his Bandung-based architectural practice Sukarno & Anwari.21C. L. M. Penders, ed., Indonesia: Selected Documents on Colonialism and Nationalism, 1830–1942 (St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1977), 302. One of his teachers in Bandung was Dutch architect Charles Prosper Wolff Schoemaker, who designed the Sociëteit Concordia’s 1921 enlargements and renovations.22C. J. van Dullemen, Tropical Modernity: Life and Work of C. P. Wolff Schoemaker (Amsterdam: SUN, 2010), 180. Sukarno and Schoemaker maintained a close friendship throughout the 1930s, and they continued to correspond even after Sukarno assumed the presidency of post-independent Indonesia.23Ibid., 56. His choice of the Gedung Merdeka as a conference venue thus tapped into his architectural expertise and can be seen as a public endorsement of his former mentor (fig. 6).

Returning, then, to Sukarno’s opening address at the Bandung Conference, his analogizing of participant delegations as “masters in our own house” is heavy with autobiographical gravity.24Sukarno, “Let a New Asia and a New Africa Be Born!” He was deeply familiar with the vast chasm in operational use between Bandung’s colonial past and its conference present, having had a hands-on role in both eras, in architectural practice and diplomatic preparations, respectively. The city’s 1955 renovations and renamings preserved—and indeed cosmetically airbrushed—the visual forms of the former society while self-consciously reconfiguring its architectural venues to a new world order. However, another metaphor of homecoming and liberatory struggle brings clarity to these aims. More than two decades after the Bandung Conference, in 1979, American civil rights activist Audre Lorde admonished that “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”25Audre Lorde, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” in This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, ed. Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa, 2nd ed. (New York: Kitchen Table, Women of Color Press, 1983), 94–101. In 1955 Bandung, dismantling was never the goal.

- 1President Sukarno, “Let a New Asia and a New Africa Be Born!,” opening address, Bandung Conference, April 18, 1955, Bandung, Indonesia. See “Opening address given by Sukarno (Bandung, 18 April 1955),” CVCE.eu [Centre Virtuel de la Connaissance sur l’Europe], University of Luxembourg, https://www.cvce.eu/en/obj/opening_address_given_by_sukarno_bandung_18_april_1955-en-88d3f71c-c9f9-415a-b397-b27b8581a4f5.html.

- 2Ibid.

- 3Ibid. The Tricontinental Conference of 1966 is widely seen as a successor to the Bandung Conference, as it built upon Afro-Asian solidarity and emphasized diplomatic relations between Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Prior to the 1966 conference, the establishment of the Non-Aligned Movement, which held its first summit in Belgrade in September 1961, is also part of this lineage, although its participants were not uniformly nonwhite.

- 4Robert Vitalis, “The Midnight Ride of Kwame Nkrumah and Other Fables of Bandung (Ban-Doong),” Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development 4, no. 2 (Summer 2013): 261–88, https://doi.org/10.1353/hum.2013.0018.

- 5Robbie Shilliam, “Colonial Architecture or Relatable Hinterlands? Locke, Nandy, Fanon, and the Bandung Spirit,” Constellations 23, no. 3 (September 2016): 425–35, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8675.12163.

- 6Christopher J. Lee, “The Decolonising Camera: Street Photography and the Bandung Myth,” Kronos 46, no. 1 (November 2020): 195–220.

- 7Naoko Shimazu, “Diplomacy as Theatre: Staging the Bandung Conference of 1955,” Modern Asian Studies 48, no. 1 (January 2014): 225–52.

- 8Ibid., 225.

- 9Photographers such as Howard Sochurek (1924–1994) and Lisa Larsen (1925–1959), both employed at the time by LIFE magazine, alongside bevies of journalists, captured stills and video reels of various airport scenes—including the beaming figure of Prime Minister John Kotelawala of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) draped in a flower garland, and the stoic visage of Zhou Enlai, Premier of the People’s Republic of China, carrying a bouquet and walking alongside Indonesian Prime Minister Ali Sastroamidjojo. See “The LIFE Picture Collection,” Shutterstock, https://www.shutterstock.com/editorial/collections/the-life-picture-collection.

- 10“Bandung is Ready,” Asian-African Conference Bulletin, no. 2 (April 1955): 6.

- 11“What It Was Like Watching the Opening Ceremony,” Asian-African Conference Bulletin, no. 3 (April 18, 1955): 14.

- 12Richard Wright, The Color Curtain: A Report on the Bandung Conference (Cleveland: World Pub. Co, 1956), 133–34.

- 13Ibid., 13.

- 14Ibid., 13–14.

- 15See Brian Russell Roberts and Keith Foulcher, eds., “Mochtar Lubis’s ‘A List of Indonesian Writers and Artists’ (1955)” and “Gelanggang’s ‘A Conversation with Richard Wright’ (1955),” chaps. 7 and 8 in Indonesian Notebook: A Sourcebook on Richard Wright and the Bandung Conference (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016); and Nina Kressner Cobb, “Richard Wright and the Third World,” in Critical Essays on Richard Wright, ed. Yoshinobu Hakutani (Boston: G. K. Hall, 1982), 228–39.

- 16Homer A. Jack, Bandung: An On-the-Spot Description of the Asian-African Conference; Bandung, Indonesia; April, 1955 (Chicago: Toward Freedom, 1955), 5. Another American visitor and unofficial delegate to the conference was Adam Clayton Powell Jr.

- 17Shimazu, “Diplomacy as Theatre,” 241.

- 18Ibid., 237.

- 19Ibid., 237.

- 20Ruslan Abdulgani and Molly Bondan, The Bandung Connection: The Asia-Africa Conference in Bandung in 1955 (Singapore: Gunung Agung, 1981), 68.

- 21C. L. M. Penders, ed., Indonesia: Selected Documents on Colonialism and Nationalism, 1830–1942 (St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1977), 302.

- 22C. J. van Dullemen, Tropical Modernity: Life and Work of C. P. Wolff Schoemaker (Amsterdam: SUN, 2010), 180.

- 23Ibid., 56.

- 24Sukarno, “Let a New Asia and a New Africa Be Born!”

- 25Audre Lorde, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” in This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, ed. Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa, 2nd ed. (New York: Kitchen Table, Women of Color Press, 1983), 94–101.