In this interview, Mexican-born, Brooklyn-based artist Laura Anderson Barbata highlights the importance of reciprocity and shared knowledge in her community-based, trans-disciplinary practice.

Madeline Murphy Turner: Dearest Laura, thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me. I’m hoping that we can start our conversation from the point when we first met. In 2014, we were introduced by our wonderful mutual friend Edward J. Sullivan, renowned professor of Latin American art at New York University. Soon after, we went to Monterrey, Mexico, where you organized a large-scale public performance to coincide with your exhibition Transcommunality: Laura Anderson Barbata, Collaborations Beyond Borders at the Centro de las Artes de Nuevo León. This performance, and the many others that are part of your ongoing project titled Transcommunality, bring together performance groups from Trinidad, Brooklyn, and Oaxaca. Can you please talk about Transcommunality, and the experience of working with people whose practices emerge from distinct and yet interconnected histories?

Laura Anderson Barbata: Transcommunality has evolved and grown through the years. As you know, it is more than a series of art projects. It also involves many long-term relationships. I began working with Moko Jumbie stilt dancers in 2002 at the Keylemanjahro School of Arts & Culture in Cocorite, which is a suburb of Port of Spain, the capital of Trinidad and Tobago. In Western Africa, Moko Jumbie is a protective spirit that, due to its towering height, is able to foresee danger and evil. The Moko Jumbie is traditionally called in to cleanse and ward off evil spirits that have brought disease and misfortune to a village. In Trinidad and Tobago, hundreds of Moko Jumbies perform during Carnival, and they also play an important role in annual Emancipation Day parades. I designed and created thematic development and costuming for Keylemanjahro’s Junior Carnival Parade presentations in collaboration with many Carnival artists from Trinidad until 2006. After that, I wanted to take the experience of all I had learned in Trinidad farther—to expand it and share it with others—and to build bridges of dialogue, collaboration, and exchange in New York City, where I have my studio.

When I was still in Trinidad, I heard about the Brooklyn Jumbies, who like those at Keylemanjahro, hail from the Moko Jumbie tradition of stilt dancing that originated in West Africa. I set out to find them. Coincidentally, in 2007, I was offered a solo exhibition in New York. I proposed a project titled Jumbie Camp, which transformed the gallery into a community work space open to anyone wishing to collaborate. During the day, for the duration of the exhibition, the space was devoted to the preparation of costuming for a street performance, and in the evening, the Brooklyn Jumbies used the gallery and street as rehearsal and stilt-dancing training spaces for youth from Bedford-Stuyvesant and Flatbush. The exhibition culminated in a large-scale street performance outside the gallery, which is on West 24th Street in the Chelsea gallery district. I saw this event as a bridge that connected stilt-dancing groups from the West Indies, West Africa, and Brooklyn. These connections are highlighted by the two main founders of the Brooklyn Jumbies: Ali Sylvester and Najja Codrington. Ali, who is from Cocorite, was trained by Glen “Dragon” de Souza, the leader and founder of the Keylemanjahro School of Arts & Culture Moko Jumbies, while Najja was trained in the Chakaba stilt-dancing traditions of Senegal. Together, Najja and Ali passed on their stilt-dancing knowledge and traditions to youth from Bed-Stuy and Flatbush. But Jumbie Camp also built bridges between the residents of Chelsea and Brooklyn, as well as put tradition in dialogue with contemporary art.

This was the beginning of what has become a long and collaborative relationship with the Brooklyn Jumbies. As you know, I am from Mexico, and I knew of Mexican stilt-dancing traditions dating back to the pre-Columbian era and wanted to learn more about them. Coincidentally (again), in 2009, I was invited to Oaxaca, Mexico, to participate in the international experimental dance festival Prisma Forum. I was interested in meeting the Zancudos de Zaachila from Oaxaca. The Zancudos—stilt dancers in the town of Zaachila—perform annually to call upon the power of their saints to give them protection, bless them, and perform miracles. I wanted to learn more about their practice, history, and traditions.

This became the beginning of an extraordinary exchange of knowledge and sharing between the Zancudos de Zaachila and the Brooklyn Jumbies. Neither group had previously known about the other: the Zancudos did not know about the practice in Trinidad and Tobago, West Africa, and Brooklyn, and the Brooklyn Jumbies were unaware of the practice in Oaxaca, Mexico. Their shared and culturally unique practice created bonds of respect and friendship that led to collaborations between the groups, and we were invited by the town council of Zaachila to return for several consecutive years to join in their annual processions—and at the end of the cultural festivities, to present the results of our collaboration.

During this time in Oaxaca, I also wanted to further expand the project by inviting local artisans to contribute to and be part of what would be presentations of their traditions: textile weaving, carving, alebrijes, novohispano altar techniques, painting, gourd carving, etc. And so I began exploring with each of the people interested in participating the different ways their work could be integrated into the whole. The results of those collaborations are the exhibition and performance that you mention—the ones that the Zancudos de Zaachila and the Brooklyn Jumbies traveled to Monterrey for—and we also held workshops and roundtables with Monterrey stilt dancers. To date, the Brooklyn Jumbies and I have performed and held workshops in the US, Mexico, Jamaica, and Singapore. Transcommunality has been exhibited in several venues in Mexico and the US, and will be exhibited at the Newcomb Art Museum in New Orleans this year.

MMT: Incredible. Thank you for highlighting that your practice is composed of so many integral participants. One of the many thematic threads I find so impactful across your artistic practice is that processes of exchange are always central. You continuously prioritize reciprocity, whether it’s between you and your collaborators, the audiences who witness the performance unfold, or even historical figures. I’d love it if you would talk about how you first came to understand the significance of this aspect of your work, as well as some of the challenges that you have faced over the years in committing to such a perspective.

LAB: As you say, these projects go beyond the performance of public experiences; they are primarily relationships that are built over extended periods of time, and reciprocity is at their core. This requires that I make a commitment to acompañamiento: to listen and learn and approach the participants and collaborators with open and continuous communication, self-evaluation and collective evaluations, because it is normal for things to change and we often need to recalibrate and refocus. In the process of exchange, in sharing and learning from each other, we agree on what we will give and what we would like to receive, and in this way, all participants become stakeholders in the project.

But for me, this way of working began in the nineties, when I was asked a simple but powerful question: “If we teach you how to build a canoe, what can you teach us in return?” I was asked this question by the Ortiz family, who are members of the Ye´Kuana community in the Venezuelan Amazon and were teaching the Yanomami community in Mahekototeri how to build a canoe. I wanted to learn, too, and to become an apprentice. Their response to my interest was to ask this question, and it influenced me profoundly, because it recognizes the role that responsibility, reciprocity, and balance have in our lives—and the importance of equally valuing one another’s knowledge and contributions. This question ultimately established the methodology for the Yanomami Owë Mamotima paper- and bookmaking project in the Venezuelan Amazon (which became my first community-driven arts project), and to this day, it continues to be the motivating factor in my work. In other words, reciprocity has become my methodology.

MMT: I’d like to delve a little deeper into the work that you have done with the Brooklyn Jumbies, particularly your ongoing project Intervention: Indigo and its connection to the Black Lives Matter movement. You and the Jumbies started this project in 2015 with an intervention in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Bushwick that began in front of the local police precinct, reminding viewers of the crisis that faces communities of color in the United States and abroad, and the dire need to change the police system. I’m hoping you can tell us more about how you conceived of this project, and how you have been thinking about it recently, in the context of the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Daniel Prude—to name just a few recent victims of police violence—and the subsequent global protests.

LAB: I started to spend time in New York in the late eighties, and in the mid-nineties, set up a studio there while dividing my time between Mexico, New York, Venezuela, Trinidad and Tobago—and wherever else my projects took me. As a Mexican and foreigner in New York, it was impossible not to have strong emotional and intellectual responses to the historically blatant systemic racism and violence toward people of color in the United States. I felt it was necessary and my duty as an artist to address this in my work; the Brooklyn Jumbies and I had discussed it in depth over the years and felt the need to find a way to respond to it through our collaborations. It took several years to finally be able to articulate it in a cohesive work: Intervention: Indigo. In 2015, the Brooklyn Jumbies, Chris Walker, Jarana Beat, and I presented Intervention: Indigo, a project that combines procession, performance, dance, music, textile arts, costuming, ritual, improvised interactions with the audience, and protest. It began at the Bushwick police precinct. The work is a call to action to serve and protect—and a protest in response to the violence and murder at the hands of the police of Black people living in this country and all over the world. The point of departure is the color indigo, a dye that is used around the globe and associated with protection, wisdom, and royalty. For example, in Burkina Faso, newborn babies are wrapped in indigo-dyed cloth to protect them. And I do not think it is a coincidence that indigo is the color of police uniforms here in the US, and almost all around the globe. It is a color imbedded with great meaning.

Six weeks before the global outbreak and lock-down because of Covid-19, in February 2020, we performed Intervention: Indigo again in Mexico City. This time, we were joined by Los Diablos de la Costa Chica, Los Rebeldes de El Capricho, who had traveled from Ometepec, a city in the state of Guerrero on the Afro-Mexican coast, to take part in the project. We started at the center plaza of the Glorieta de los Insurgentes, facing two significant buildings: the Secretaría de Seguridad Ciudadana CDMX [Ministry of Public Security of Mexico City] and the Fiscalía General de la República [Attorney General of Mexico]. The figures of Rolling Calf, performed by Chris Walker, and Little Jaguar, who I portrayed, initiated the intervention at the center of the roundabout, and were joined by Los Diablos in a choreographed symbolic call for justice and protection, which we directed toward the institutions we were facing and to all citizens. It is important to note that the Mexican Constitution did not officially recognize our Afro-Mexican population until 2018. An estimated two million Afro-Mexicans inhabit the coastal states of Guerrero, Oaxaca, and Veracruz. In 2020, for the first time, the Mexican census allowed for self-identification as Afro-Mexican, Afro-descendant, or Black.

In Brooklyn and in Mexico City, as we made our way around informal street vendors, through traffic, residential areas, and artist neighborhoods, we were joined by the rest of the performing artists and by onlookers, who not only followed us but also became an integral part of the unfolding narrative. As we moved through the streets, we transformed them and our relationship with public space—and we offered a new narrative, one that demands visibility, recognition, and justice for all Afro-descendant and BIPOC communities. Through the act of intervention, we exercise our right to occupy public space, and in doing so, express our defiance as we symbolically appropriate what is ours and demand protection. We do this while wearing the color that symbolizes care and service but also the repression of QTBIPOC communities.

MMT: Thank you so much for those very powerful and crucial words. I’m especially interested in what you say about the only recent recognition of Afro-Mexican populations. In thinking about the work you are doing for Intervention: Indigo with these communities, and many other projects of yours that we don’t have time to get into today, it seems that there is an aspect of your practice that is deeply committed to people and histories that have been expunged from “official” narratives.

LAB: During the recent global health crisis and lock-down, it has become evident that governments and institutions meant to serve their populations were incapable of attending to the most basic needs and rights of the people. And it was during this time that we witnessed—once again—the brutal murder of African-American people, the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Daniel Prude, among many others who have tragically lost their lives at the hands of the police. These horrific acts of violence, injustice, and hate mobilized massive protests around the world to demand change; to demand the dismantling of the racist, sexist, and white supremacist systems that continue to deny the rights of QTBIPOC communities; to demand that the ongoing discrimination be reckoned with and to affirm the responsibility that white and privileged communities and institutions have in dismantling this violence; and to demand change. The BLM movement continues to press forward to bring about awareness and equality for QTBIPOC communities. There is no going back to the time before Covid-19—global economies are crumbling. It is a time to unite in a commitment to real change on both social and personal levels, to build a future in which justice and equal rights are honored. It is a time to support our most vulnerable communities. It is OUR responsibility as citizens of the world to serve and protect each other and to stand up for our Black Brothers and Sisters.

MMT: Through your social practice, you have also confronted the global climate crisis. I had the joy of witnessing the performance of Ocean Calling, which you created on the occasion of World Oceans Day at the United Nations Plaza during the first United Nations Ocean Conference in New York City in 2017. Since 2016, you have pursued several projects dealing with climate change and that compel audiences to acknowledge the need to protect our oceans. I’m hoping you can tell us more about these projects, and how you think about the environment or the natural world in relation to your community-based practice.

LAB: The environment has been an interest and concern of mine throughout my career. I began my practice making works in the studio—drawings on paper, sculpture, and outdoor installations—that address nature and the environment. I also initiated community projects in the Venezuelan Amazon that combined environmental protection and the preservation of oral history in the communities through paper- and bookmaking using local materials. This background and experience are the reasons that I was invited in 2015 by curator Ute Meta Bauer to be a fellow of Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary’s TBA21-Academy, which is an ambitious, innovative program to bring awareness and find solutions to environmental crises such as global warming and the need to protect the oceans. The program brings together scientists, researchers, curators, and artists to embark on exploratory trips by sea to different parts of the South Pacific. I participated in an expeditionary trip to Papua New Guinea. As part of the program, all of the participating fellows were brought together after their trips to exchange ideas, to share our experiences and findings with different communities, and to listen to these community members’ experiences and responses to our work. This is the genesis of the performance at the UN in 2017, which was commissioned by Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary–TBA21 Academy.

Ocean Calling, is a cross-disciplinary work created in collaboration with artists from the Caribbean diaspora and Mexico, and it is inspired by all forms of life that make the ocean their home—as well as by the people and the histories and cosmography of the communities that for millennia have lived in close relationship with the ocean. The resulting work combines spoken word, dance, improvisation, stilt dancing, ritual, procession, costuming, sculpture, and music to create a form of storied performance that unfolded at the United Nations Plaza after the first United Nations Ocean Conference in 2017. It was presented in a highly political space at a crucial moment, and in New York City, a metropolitan environment that is extremely dependent on the health of the oceans—even though this may not be overtly obvious to urban communities.

During the performance, I read aloud the declaration signed by the Pacific Island Countries and territories to significantly improve ocean governance. This statement was drafted during the Pacific Regional Platform for Partnerships and Action on Sustainable Development Goal 14 meeting, which took place in Suva, Fiji, just months before the UN Ocean Conference. It led the way to action on SDG 14: Sustainable Development Goal 14, and the work highlights the global impact of the collaboration among the Pacific Island Countries and territories on significant policy changes.

MMT: I’m really interested, Laura, in what you say about the unrecognized impact of oceans on the urban environment, especially given how as humans, we often, incorrectly, think of the urban and the “natural” environments as such distinctly different spheres. Your perspective is so important, because, as you have beautifully elaborated, you have worked with communities ranging from those in the middle of the Amazon to those in the center of New York City. How do you see your interest in the environment arising or unfolding across these different sites?

LAB: Perhaps my interest in the ocean is rooted in the fact that I grew up in Mazatlán, a coastal town (now a city) in the state of Sinaloa. Every day we woke up to the ocean, and the beach was where my sisters and I would play and explore for hours after school. We had no interest in toys; the beach and the ocean had everything: it is a place of marvel, a place that is different every day; it is teeming with life on the surface, in the sand, and in the water; sunsets are spectacular and different every day, with millions of colors painting the sky. It is a place of delight as well as of mystery. And as children, it was not unusual for us to be woken up in the middle of the night by a loudspeaker telling us to evacuate the area because of the possible dangers of an approaching ola marina [tidal wave or hurricane]. We were continually reminded of the powerful presence of nature, and of the importance of listening to it, respecting it, and getting out of its way when necessary. Nature was just part of life.

I think that I was also impacted and informed by having spent so much time in the Amazon rainforest of Venezuela, a place where you experience your relationship with nature and the environment in a very direct way. Nature dictates everything, all activities: health, productivity, mobility, life, and death. One must learn to commune with this reality wholeheartedly, and to do so with humility, with respect, and with gratitude—and if you can do that, you will be able “listen” to it and to learn.

As I mentioned earlier, the environment has been an ongoing concern of mine. In 1992, I was living in Mexico City and the subject of my work was the environment: seeds, nature, cycles of life in the natural world. One of my drawings from this time received an award at the exhibition Eco Art 92 at the Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro (MAM), which was held in conjunction with the 1992 United Nations Earth Summit. It was a hopeful moment, as that conference yielded Agenda 21, the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, which was adopted by 178 governments, and laid the groundwork for environmental protection safeguards for the twenty-first century.

At this current stage of my life, when I do the math, I have mostly lived in cities, primarily in Mexico City and New York, both megacities. What has always surprised me about urban life is how easy it is to disconnect from the environment. I don’t want to say the obvious, but I have to: our urban lifestyle is designed to make life more convenient and comfortable in order to meet the demands of capitalist ideals. Discomfort must be avoided, and that means not accepting, looking at, or even acknowledging what is uncomfortable or unpleasant: greenhouse gas emissions, global warming, rising ocean levels, climate refugees, poverty, slave labor, climate, jobs, and justice. These crises are interconnected and we have been taught to turn a blind eye to them.

Now, at the start of the second decade of the twenty-first century, I look back on the progress spurred in 1992, which marked an important shift in global policy and social consciousness in terms of the protection of our environment and the communities that live in close relationship with it. However, these gains stand at risk of being systematically erased and replaced with shortsighted agendas that serve the privileged few. To feel discouraged by this reality only paralyzes us. We have the opportunity to make an impact, beginning by recognizing that our personal choices have tremendous power. We can inspire others to take a stance and to change the values and practices of private industry and policy. We are at a crossroads. I created Intervention: Ocean Calling and Ocean Blues in response to these issues, and although these works in themselves will not solve the problems we are facing, they can inspire necessary conversations, and ultimately, ideally, make some waves.

MMT: As we can see in the wearable artworks that you create for Transcommunality, Intervention: Indigo, Intervention: Ocean Blues, among others, textiles are integral to your work, not just in their visual effects, but in the meaning and stories that they communicate. Can you take a moment to talk about this element of your practice? How did your interest in textiles develop, and how do you conceive of the links between the very detailed, contemplative, and minuscule process of creating these materials and the large-scale nature of your performances?

LAB: My work in Trinidad and Tobago introduced me to the role that textiles play in public processions and performance. It was through assisting the Keylemanjahro School of Arts & Culture Moko Jumbies that I saw the potential that textiles have to convey an impactful message. Not only are they the foundation of the costuming for the youth participating in Junior Carnival, but the larger-than-life scale of the characters on stilts enable exploration in terms of movement, scale, and narrative. The physical characteristics of each of the textiles, along with their embedded symbolism, allowed me to utilize them as an integral part of thematic development and character design.

Because creating Moko Jumbie costumes requires a significant amount of fabric, I often recycle textiles from past projects and combine them with newer materials sourced locally in markets in my native country. I am also very interested in repurposing discarded materials that I have collected from numerous sources, such as Mas camps in Port of Spain; in New York, I collected discarded CDs as well as fabric scraps from the North American company Victor Textiles. Each piece of cloth holds a story within it, and by putting them together, I create dialogues between them that can be communicated through the dancer and expand their meaning.

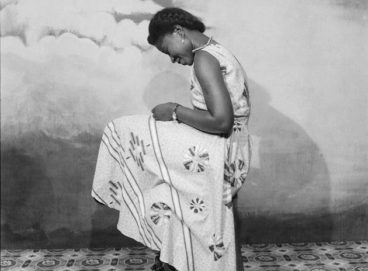

The Transcommunality project was developed further in Oaxaca and scheduled to be exhibited at the Museo Textil de Oaxaca. The museum’s director, Hector Meneses, introduced me to extraordinary textiles from their collection and educated me about their uses and traditions within the different weaving communities of Oaxaca. During my research in Oaxaca, I was also eager to meet master artisans specializing in alebrijes, church restoration, wax flower candles, gourd carving, weaving, and embroidery who I invited to produce elements for new costumes to be worn by the Zancudos de Zaachila and the Brooklyn Jumbies. I met with each of the master artisans to discuss and plan their contribution; some chose to have complete freedom, while others were interested in responding to specific interests that I expressed. And in the case of Intervention: Indigo, the characters are made with indigo textiles that were handwoven and dyed in Burkina Faso, Guatemala, Japan, and the United States as a point of departure in addressing the use and misuse of the color blue by those whose duty it is to serve and protect. Indigo is one of the oldest plant-based dyes, and it is used all over the world and ritually embedded with symbolism and spirituality, power, and nobility. The color historically represents absolute truth, wisdom, justice, and responsibility. The textiles are embedded with this information and are central to the work itself.

MMT: Recently, we were talking about your position as an artist who works between Mexico City and New York City. How do you think this element of nomadism or transversality, if I may call it that, has impacted your perspective and work?

LAB: As a Mexican-born, New York–based artist, it is my belief that a shared artistic and social practice can serve as a platform on which to connect, learn, exchange, create, and transcend borders in order to activate one’s sense of belonging—locally and globally—and our shared responsibility toward the welfare of one another.

It is undeniable that I have learned from and been impacted by the opportunity of having worked in Mexico, Venezuela, Trinidad and Tobago, the United States, and Norway. I mentioned before how a question I was asked in the Venezuelan Amazon clarified for me the way in which we can create platforms of reciprocal exchange that are rooted in respect. And this has become the fundamental philosophy of my work. But also, working in different parts of the world with many people has impacted my intervention work. For example, Intervention: Indigo is informed by my homeland of Mexico, which has a rich legacy of ritual public processions and celebrations—as well as protest—the importance of the occupation of public space through processional performance from my work in Trinidad and Tobago, and my research on textile traditions and material culture from around the globe. As artists, we can unite to name the forces that are oppressing our societies and identify a common purpose by using all the forms of creativity we have available—dance, music, stilt dancing, spoken word, the creation of ritual space through interventions, and the creation of wearable art from textiles. These expressions have the capacity to cross boundaries, and they invite us to honor traditions. Through the process, we recognize ourselves in the work and build art-based social-practice projects that result in long-term exercises of reciprocity and collaboration.

MMT: I’d like to conclude by asking you about your activities during the pandemic. I’m thinking especially about your incredible initiative to make face masks, which you then donate to neighbors, hospitals, and homeless shelters. While it is an emergency response in an unprecedented moment, I think your effort to make and distribute masks also, almost surreally, aligns with your broader artistic practice in its very concrete commitment to the communities in which you live and work.

LAB: In a way, I feel that my work has come full circle, and I’m still trying to understand my role as an artist in the future. For now, what to do has been absolutely clear to me. As I mentioned earlier, shortly before the COVID-19 outbreak, I had presented Intervention: Indigo in Mexico City. This experience was still very much present in me and I was still processing it, which is normal after a solo exhibition—and especially after one of my interventions, which as you know, are few and far between. And so I returned to Brooklyn and shortly thereafter, I was facing the onset of COVID-19, and it was absolutely clear that it would disproportionately impact our Latinx, Native American, and Black communities. My first impulse was an urgent need to respond with whatever skills and materials I had available, and the answer as to how to do it was right in front of me. I immediately gravitated to the Indigo project textiles I had in the studio, and I started making masks to donate. I was sewing nonstop until I had completed a big batch, and then I set out to find people and places that needed them. At the beginning of the lock-down, essential workers in the local deli markets were not being given masks—yet they had long and crowded subway commutes from Queens and the Bronx to my neighborhood in Brooklyn. The homeless shelter around the corner from where I live was also not receiving PPE for its staff or residents, and the director of the shelter was desperately trying to find face masks to distribute. I contacted a community group based in the Bronx that was also in need of masks, and I posted a sign on my building for neighbors to contact me if they needed them. The need was, and still is immense. So I went from making masks for stilted characters, which can be up to almost twenty feet high, to—in the spirit of Intervention: Indigo—making face masks to protect and to serve our BIPOC communities. The project Intervention: Indigo gained new meaning for me, and I have continued to make and distribute masks.

I also knew early on that Mexico would be impacted in unimaginable ways due to social, economic, and political inequities, and so I made several tutorials in Spanish on how to make masks by hand. These were circulated through social media by cultural institutions and museums in Mexico, and projected around the clock on a large screen on the street. The tutorials were also circulated in the US in Spanish by community centers that serve Latinx communities. World leaders—including those in Mexico and the US—were behaving as if they could minimize the effects of the pandemic by merely ignoring the crisis. Believing that they had to choose between economies and health, they ignored medical experts and created a narrative that contradicts scientific facts and statistics; all around the globe, we are seeing that the systems that serve the needs of citizens are inadequate and failing. This only fueled in me the urgency to continue making and distributing masks, and we all had to act quickly. But it also made clear why it is more important than ever to create networks of support for one another.

To date, I have made and donated approximately two thousand masks—to hospitals, shelters, clinics, neighbors, and friends, and to people in Queens, the Bronx, and Texas, and on Native American Reservations in Montana. As I began donating masks, the people receiving them responded in beautiful ways. They have sent me tortillas, beans, maseca, jalapeños, flowers, cheese, and fabric, among other items, in exchange for the masks. People I do not know have been reminding me of and reintroducing into these efforts the driving force behind my own work, which is the importance of recognizing each other’s labor, each other’s value, each other’s work, and each other’s knowledge, and of responding through balanced exchange, through gestures of reciprocity. This is the essence of mutual aid.