James Barnor (b.1929) is a pioneering figure in Ghanaian photography. He documented the decolonizing processes and realities of the postcolonial context in Ghana, as well as the diasporic, metropolitan life in London. Between studio photography and photojournalism, the work of James Barnor captures identities and societies in transition. His career, spanning six decades, bridges continents and photographic genres to create a transcultural narrative consistently driven by his passionate interest in people.

Photography as a new technology prefiguring the modern era was appropriated almost simultaneously across the world. George A.G. Lutterodt and his son Albert founded the first portrait studio in Accra, Ghana in the late 19th century. The increasing desire to be photographed led to the establishment of permanent studios in most West African capitals as early as the 1900s. Cameras and films were rare commodities and the position of the photographer was regarded with particular respect. From passport pictures to portraits and group compositions, the act of being photographed was considered a special occasion to mark a life-changing moment, often a wedding or graduation. The subject would dress in their finest attire and pose in front of a backdrop textile, initially imported from England and reminiscent of a wealthy colonial interior. 1“This was especially visible with the backdrops imported from England. All photographers had their own backdrops and props, these would show affluence and a certain British influence.” James Barnor, James Barnor Ever Young, edited by Renée Mussai (Paris: éditions Clémentine de La Féronnière, 2015), 17. In the absence of an educational institution for photography, the craft and know-how was transmitted from the studio photographer to his apprentices. Therefore, when, in 1947, eighteen-year-old James Barnor decided to become a photographer, he asked his cousin J. P. Dodoo for a two-year apprenticeship in his portrait studio. Whether it was the allure of photography, the increasing circulation of photographs in everyday life or the authority of the photographer’s position, Barnor felt compelled to try it.2“The first photographers I remember were the police photographers: when there was an accident or crime scene, one particular police photographer would turn up and act as if he were the ruler of the whole scene […] He would control the entire place. So that caught my eye in the first place […] So photography was “in it”, in Ghana at the time when I grew up. […] Many of my relatives were photographers.” Ibid., 17.

Accra moving towards Independence

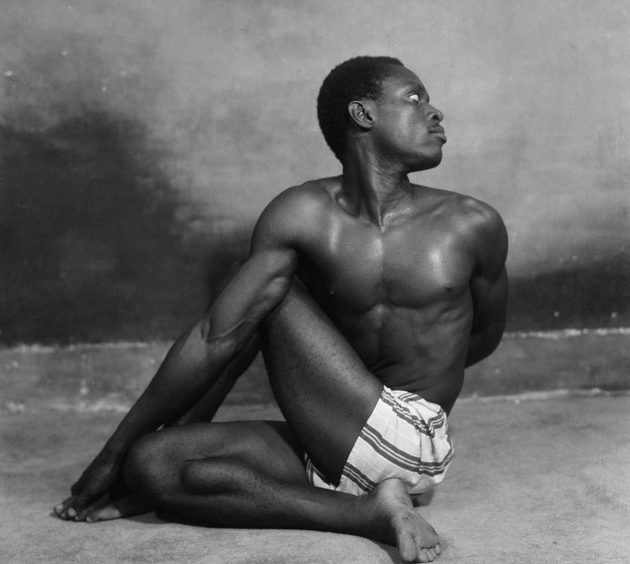

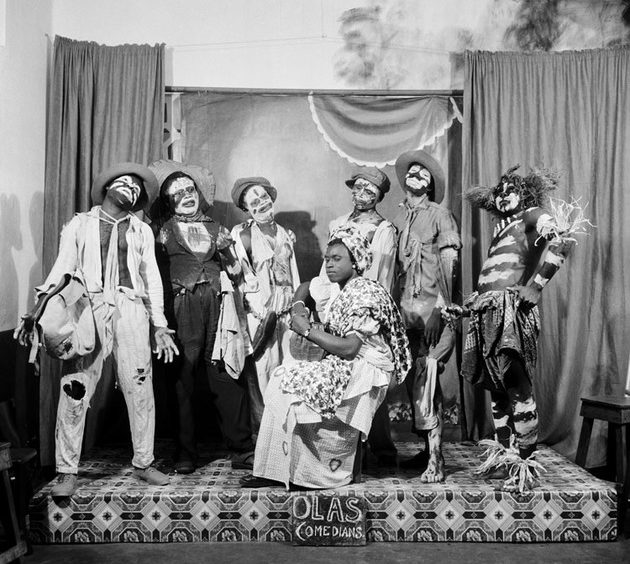

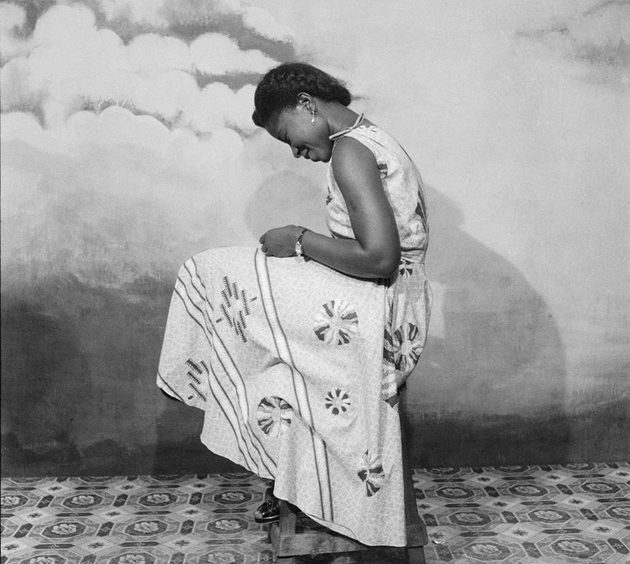

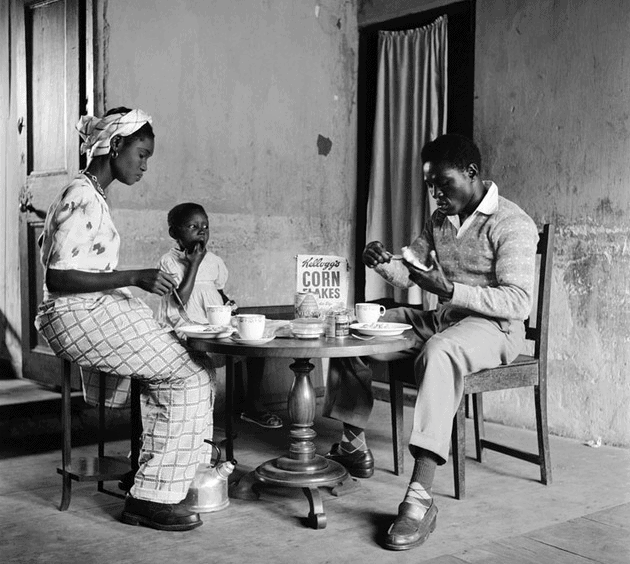

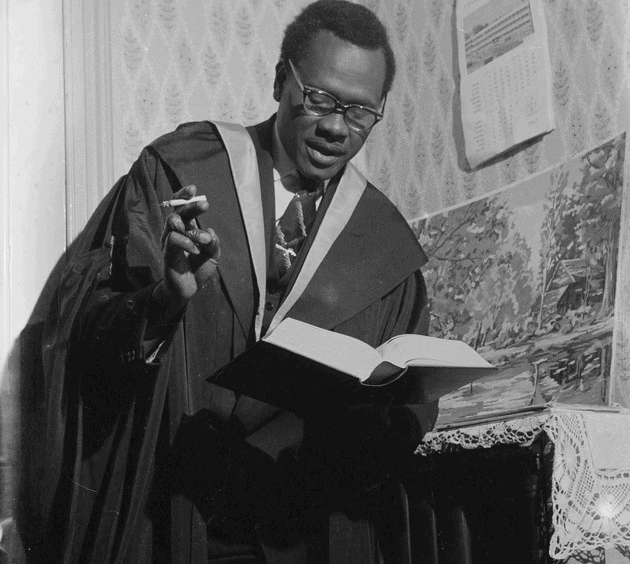

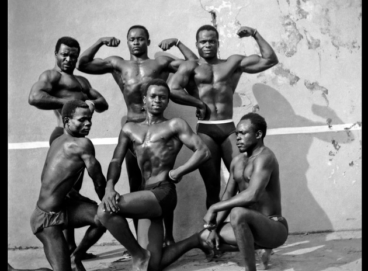

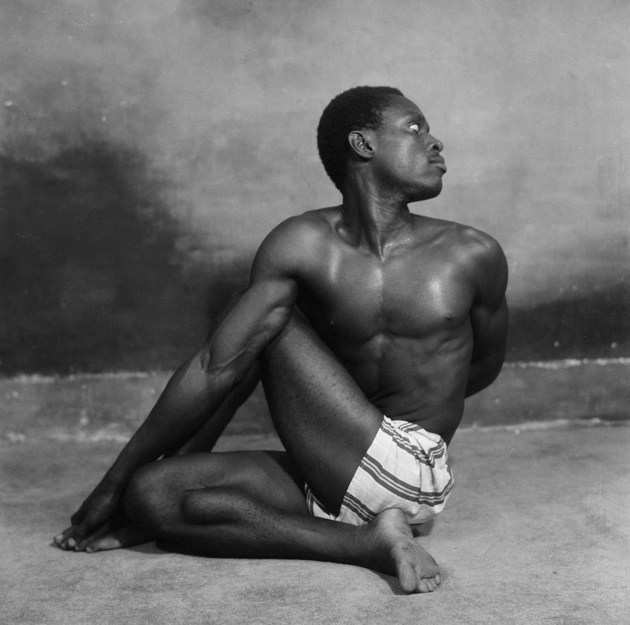

James Barnor’s first portraits were staged outdoors, using natural daylight and borrowed equipment, backdrops and props. His first studio Ever Young opened in Jamestown in 1953 (fig. 1) and quickly became a pivotal center for a diverse clientele consisting of newlyweds, young women and pastors, nurses and yoga practitioners, civil servants and performers (fig. 2-5).3A permanent protagonist in Barnor’s pictures of the time is a porcelain figurine, which would become the trademark of his portraits until 1955 when one of Barnor’s children broke it. Ibid., 82, 85. This body of work establishes the principal aesthetics of Barnor’s photography: a deep appreciation, tenderness and protectiveness towards youth, elegance and feminine beauty. Simultaneously, his pictures testify to an ongoing social shift: the subjects distance themselves from the colonial canon, gradually embracing their traditional Ghanaian clothing and kente textiles and choose to be represented in less formal poses and arrangements (fig. 6). This almost unnoticeable transition cannot be viewed separately from the writings of Nnamdi Azikiwe for the African Morning Post in the ‘30s, the discourse of Léopold Sédar Senghor in the ‘40s, the fifth Pan-African Congress in 1945, the boycott of overpriced imported European goods and the anti-colonial riots of February 1948 in Accra, and finally the arrival to power of Kwame Nkrumah and the CPP (Convention People’s Party) in 1951. The studio pictures of James Barnor are indicative of a rigorous and burgeoning pre-Independence Gold Coast and draw attention to the tensions between the local, the intuitive, and the spontaneous, on the one hand, and the formal, the staged, and the prescribed on the other.

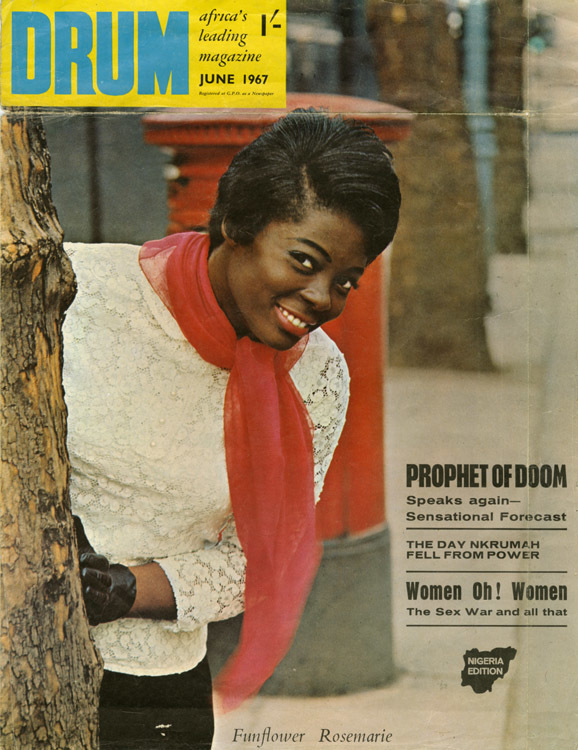

However, the major social, political, and historical transformations of African subjectivity in the ‘50s are documented more explicitly in James Barnor’s work as a photojournalist. A decisive moment in Barnor’s formation was his exchange with another cousin, Julius Aikins, also a photographer, working for the West African Photographic Services, who introduced Barnor to the work of other photographers through books, magazines, and literature.4Circulation of information has consistently been a challenge across African countries, and was especially marked between Anglophone and Francophone colonies. James Barnor says he did not know of the practices of Malian Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé or Nigerian J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere at the time. Although working at the same time and preoccupied with similar subject matter, Barnor he only became aware of these similar bodies of work later when they received broad international attention. Ibid., 18. See also this interview. Already during his apprenticeship, Barnor came to appreciate the storytelling aspects of photography and began venturing beyond the static space of the studio, the theatricality of the set-up, and the rigid big-plate camera. With his first owned camera, a Kodak Baby Brownie that took eight frames on 127 film, Barnor turned the city into his studio, satisfying his enthusiasm for experimentation and exploration.5The transition from the studio to the street was not uncommon for many West African photographers, including Malian Malick Sidibé, Nigerian J. D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere and Burkinabe Sanlé Sory. Ibid., 18. When Cecil King, chairman of the British media group Daily Mirror, came to Accra to inaugurate Daily Graphic, he approached James Barnor who photographed for the first paper in 1950.6“I remember when Cecil King, who was the chairman of the Mirror group, came to Accra in 1950 with the idea of establishing a press. He already had a press group in Lagos, Nigeria and wanted to do something similar here. So he came with a team including McLellan, a veteran photographer from England, and they were looking for a photographer to start the paper. They were directed to my cousin Mr. Dodoo, who said, ‘I do not do this sort of work,’ but he sent his little boy to me. […] I didn’t expect then that I would be working for anybody and didn’t have a portfolio to show people. As he looked through my box of prints, he said ‘Not quite, but we will train you.’ I started working in September and the first paper came out in October 1950.” Ibid., 21. Approximately a year later, Barnor began to work on a freelance basis for the anti-apartheid South African Drum magazine for lifestyle, culture, and politics, which would evolve into a long-time affiliation.7The rise of the new states gave rise to numerous official press agencies, such as AMAP in Mali, Congo Press in Congo-Kinshasa, Silly-Photo in Guinea, and ANTA in Madagascar. […] Drumfeatured work of some of the best black photographers. It was a vehicle that exerted subtle political pressure without jeopardizing its existence under draconian apartheid rule. It also recorded the vital cultural life of urbanized South Africans and thus promoted a positive expression of black urban resilience. Pierre-Laurent Sanner, Kelly Berman [eds], Eye Africa : African photography 1840-1998 (Cape Town: Eye Africa Project, 1998), 16.

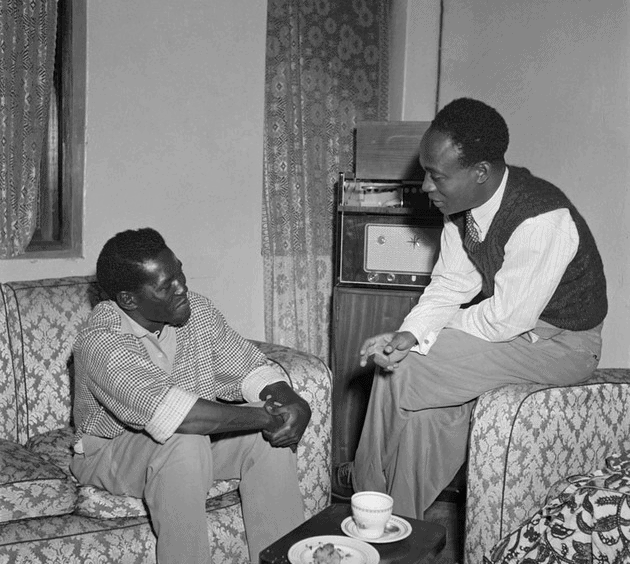

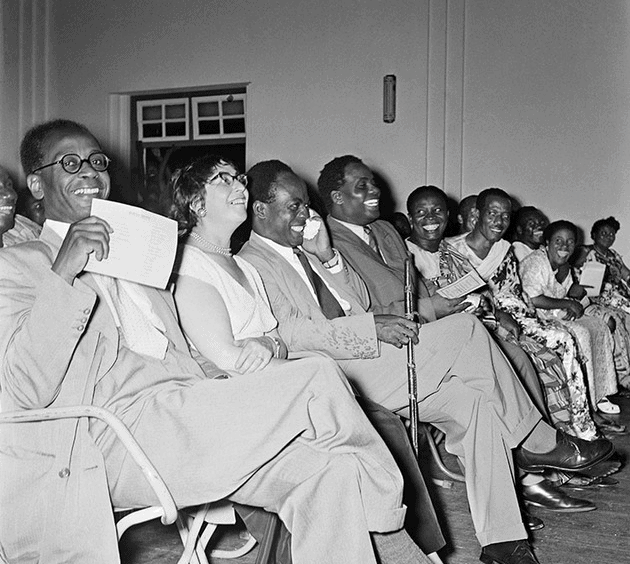

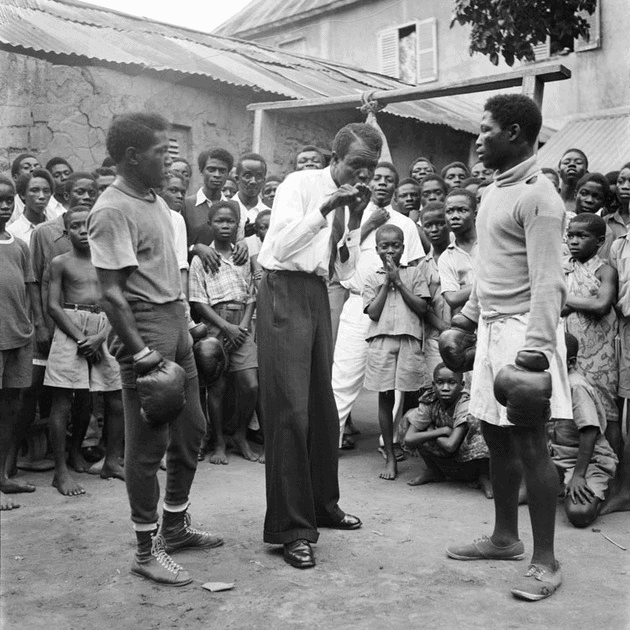

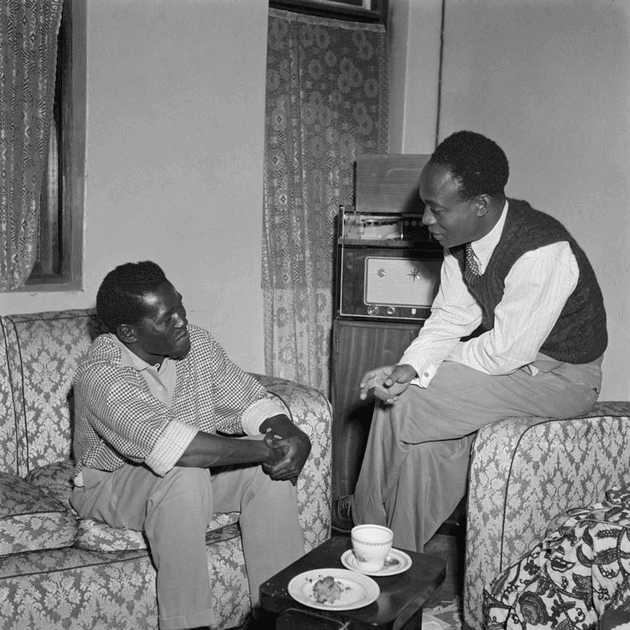

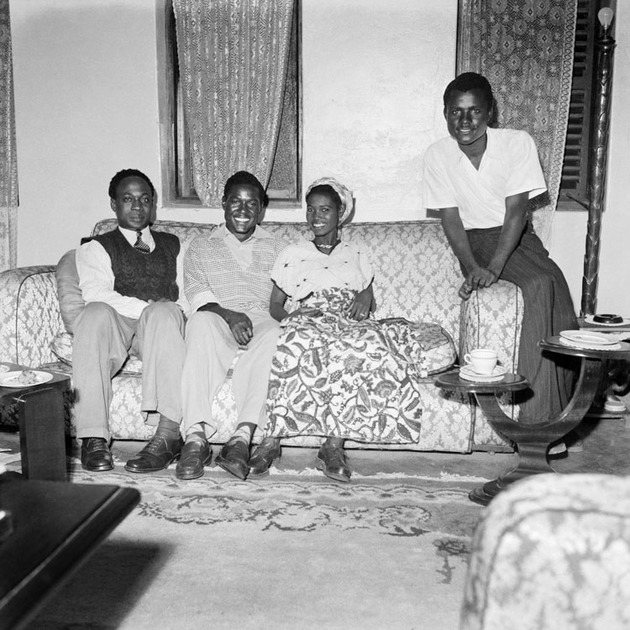

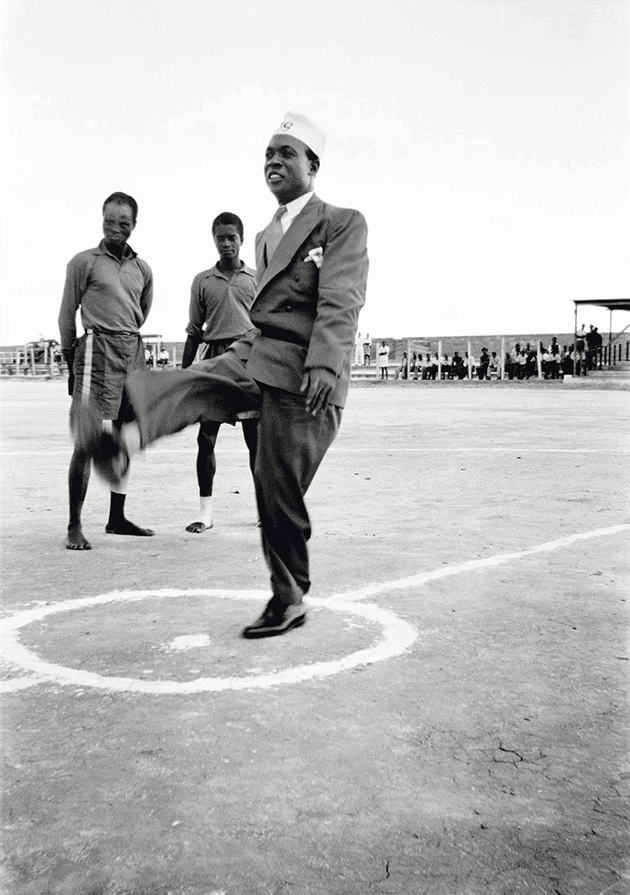

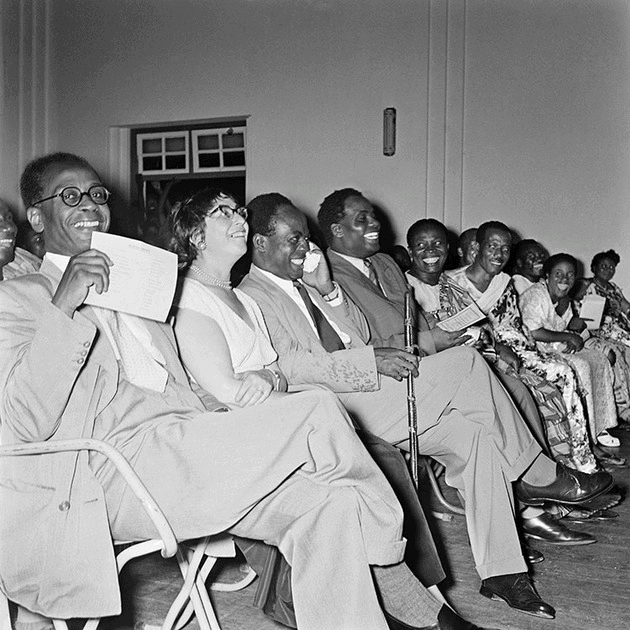

Whether on professional assignments and reportages or on his own initiative, Barnor documented the cosmopolitan living of Ghanaian society as it was coming into being. Pictures of weddings, parades, beach parties, and spontaneous festivities on the street illustrate the lightness of the yearlong summer, the fusion of rhythms, the communal spirit, the youthful playfulness of everyday life. Representative of this era are the photographs of 1952 when James Barnor followed the boxer Roy Ankrah in an early example of celebrity reportage. Barnor sets out to build the portrait of the athlete through a series of photographs of matches in public space, intimate moments with his family, and a visit to Kwame Nkrumah (fig. 7-9). Beyond just the portrait of a historical figure, one could argue that Barnor here constructs a portrait of the historical moment; his pictures become historical in the sense that they bear witness to the multidimensionality of experience in the wake of independence, perhaps even lending a voice to the processes of decolonization. They are inexhaustible studia, as Roland Barthes would put it: they inform, represent, cause to signify. Documenting an event that is unarguably historically significant is the self-portrait of James Barnor with Kwame Nkrumah, Roy Ankrah and his wife Rebecca in Nkrumah’s living room (fig.10). “We were together for about an hour just talking, taking photographs and having tea at Nkrumah’s home. At the end, I set up my camera and tripod for a portrait of the four of us. With the Leader of Government Business already on the sofa, I decided to sit up on the edge, not realizing that they’d moved and made space for me… I would have liked to be closer to them, but that didn’t happen,” Barnor recollects.8Barnor, Ever Young, 50. Despite the historical significance of the photograph, it simultaneously invokes Barthes’ punctum: his positioning on the edge of the sofa is the accident that pricks and pierces, offering up an unapologetic liveliness arising in the moment between the click and the closing of the shutter. 9“For culture (from which the studium derives) is a contract arrived at between spectators and consumers. The studium is a kind of education (knowledge and civility, “politeness”) […] this second element which will disturb the studium I shall therefore call punctum: for punctum is also sting, speck, cut, little hole and also a cast of the dice”. Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida Reflections on Photography (New York : Hill and Wang, 1981), 27-28.

Fig. 10. Self-portrait with Kwame Nkrumah, Roy Ankrah and his wife Rebecca, Accra, c. 1952. Courtesy of the artist and galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière (Paris).

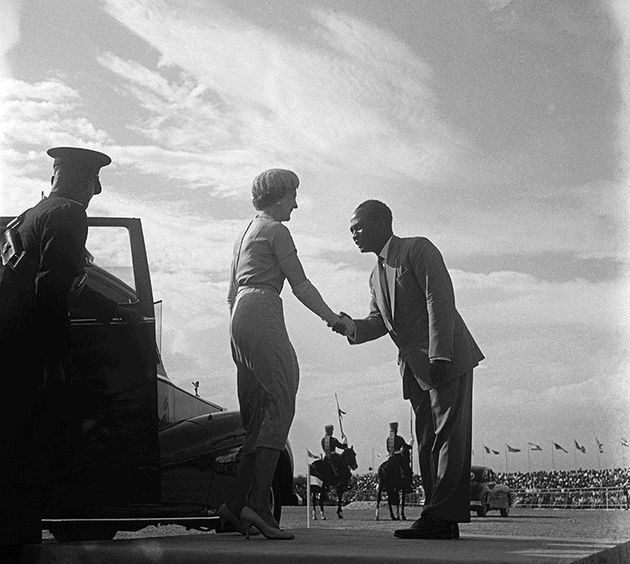

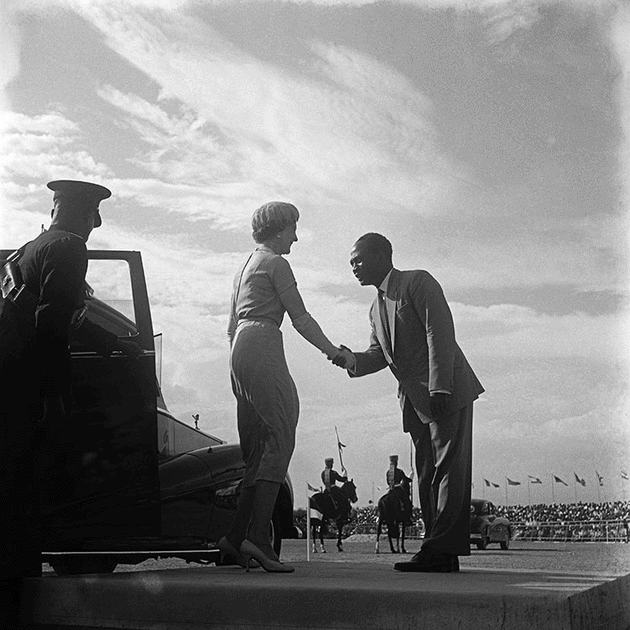

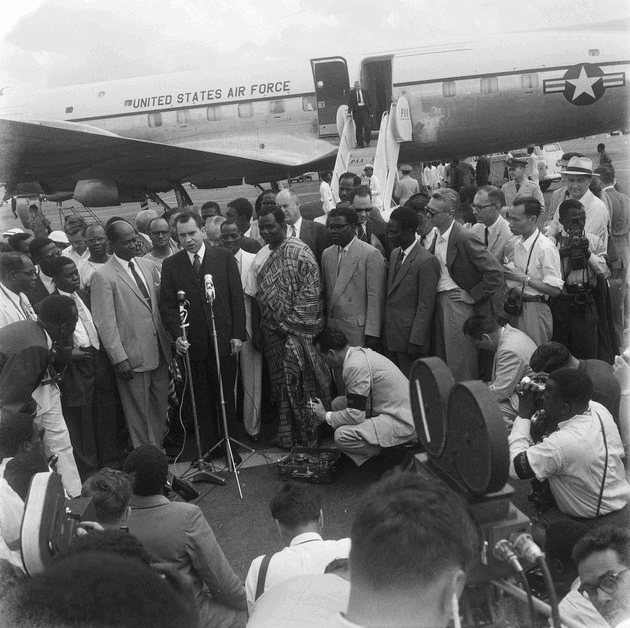

Following and documenting his times, Barnor was able to capture Kwame Nkrumah in various occasions beyond the comfort of his living room, spanning from his release, along with his Convention People’s Party colleagues, from the James Fort Prison in 195110“He had been a political prisoner detained by the British Colonial government but was freed after winning the seat in the general election for Accra Central contingency. I took two or three pictures, and for the rest of the month I was printing and selling them in the market and the streets of Accra”. The value placed on Nkrumah’s photograph testifies to the people’s desire for a leader who represented them, manifested by the purchase of his likeness to be positioned in their homes. Ibid., 55. to dance parties and concerts at Rogers Club or Cape Coast (fig. 11-12). Barnor’s tracing of this political figure also includes March 1957 and the days marking the country’s Independence. He took his box camera and went out on the street to witness and immortalize the festivities of a nation in its infancy (fig. 13-14).11“So we walked the streets of Accra. We finished up at the Old Polo ground, where the Nkrumah Mausoleum is now- right opposite Parliament House. From there Nkrumah and his people spoke to the crowd from a stage that was built. I remember Jim Bailey and I were standing right in the front. I took pictures of Nkrumah declaring, “Now Ghana is free”. Unfortunately I sent all those pictures away to South Africa for printing”. Ibid., 23. His films were sent to South Africa for processing and were delayed, so his pictures were never published in the newspapers.12“My images were delayed and so they never made it to the papers”. Ibid., 57.

Vibrant London and the diasporic experience

Two years later, following the pivotal turning point of Ghanaian independence, James Barnor moved to London. It was time for the Swinging Sixties of a multicultural metropole and Barnor was thirty years old. As a photographer for Drum, assistant at the Colour Processing Laboratory, student at Medway College of Art, and as a protegé of Dennis Kemp at Kodak Lecture Service, he had the chance to photograph emblematic figures of his time, with the city’s most celebrated landmarks as background. His photographs have a quality that might be reminiscent of stills from an Antonioni or a Hitchcock movie. Yet, not quite, because Barnor documented a diasporic black community in the UK, a reality distinct both from the rise of Black Power in the US in the 1960s, but also from the dominant culture featuring Twiggy and The Beatles in London. In 1968, the year Enoch Powell, British Member of Parliament, gave his “Rivers of Blood” anti-immigration speech, James Barnor’s photography seemed to insist on the representation of a blackness that cannot be fixed or framed within one nation, one identity, one dimension.

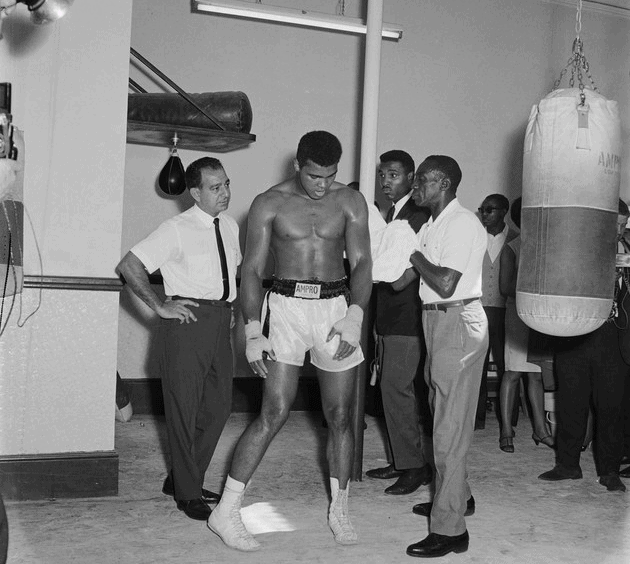

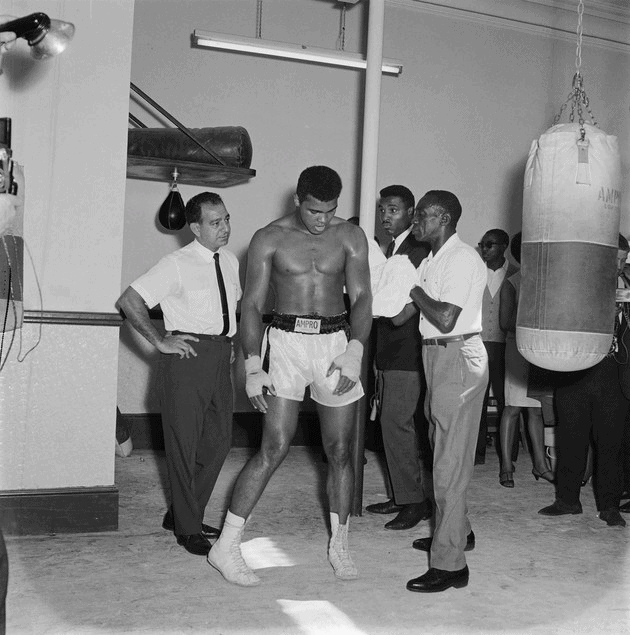

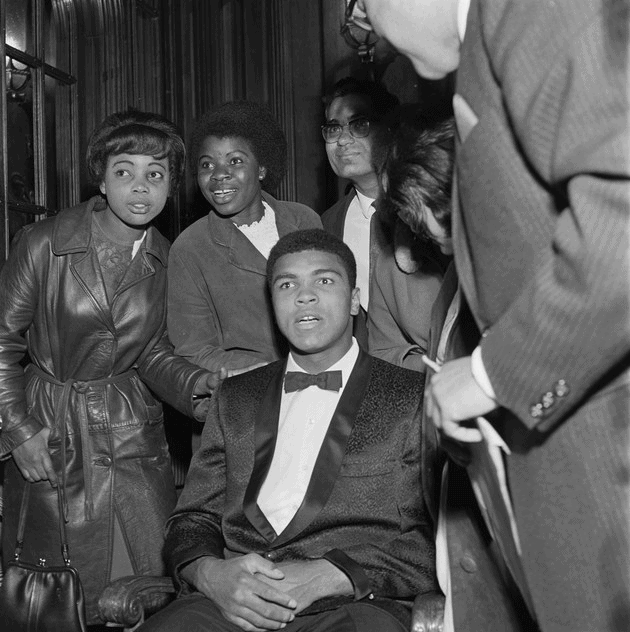

The number of films in his archives from the 1960s point to an insatiable photographic practice and the willingness to push the medium as far as the available means would allow. He followed BBC news presenter Mike Eghan to Piccadilly Circus (fig. 16) and boxer Muhammad Ali at Earls Court (fig. 18-19); he photographed models at Trafalgar square, in studios and on the street; friends at parties; public holidays and parades. His cover photographs and fashion images were distributed internationally, reaching readerships in Nigeria, Kenya, as well as South Africa. Echoing the idea that photography, and portraiture in particular, is premised on the artifice of self-construction,13Walther Collection, Events of the self : Portraiture and Social Identity, Contemporary African photography from The Walther Collection, ed. by Okwui Enwezor (Göttingen : Steidl, 2010), 26. the figures in Barnor’s photographs, rather than being depicted and displayed, seem to insist on being seen, looked at and admired. A sense of optimism and an appreciation for life pervade these portraits. Barnor resists depicting signs of exclusion, marginalization or segregation, rather directing the camera’s gaze to his confident, seductive, individual subjects. Whether models or friends, the images often seem to evince an exchange of glances between the camera and the subject photographed, in some cases as if sharing a common yet unspoken connection that is then passed on to the viewer of the eventual printed image (fig. 20).

Return and Color Photography

A feeling of responsibility and an awareness that “civilization flourishes when men plant trees under which they never sit”14Barnor, Ever Young, 28. and a need to share his experience and his knowledge with younger Ghanaian photographers, led James Barnor back to Accra in the early 1970s.15“But I am always thinking of what I can do to help Ghana, because not many people had the opportunities that I had… I wanted to pass on some of my knowledge, which comparatively, was above a lot of photographers in Ghana.” A sense of longing for his native context is also evident in a quote describing when he visited Ghana with a friend from Europe: “I took him to our cocoa farm, and we visited the West African Cocoa Research Institute. He was there for four days, and on the second day he said ‘But James, why did you leave all of this to come to London?’ It still rings in my mind…” Ibid., 26-28. The occasion was the opening of a technical advisor position for color photography, which Agfa Gevaert was introducing to Ghana. Barnor’s experience with the Colour Processing Laboratory in London was invaluable as he opened and managed the first laboratory in Accra. Meanwhile, he continued his practice not only as a photojournalist, but also as a studio photographer following the opening of Studio X23, his second in Jamestown, named after his postal box number. He worked for various advertising campaigns, for the United States Information Service and then as a government photographer for the military leader that followed Nkrumah, Jerry John Rawlings.

The introduction of color photography made it possible for Barnor to work fully with the varied palette, patterns, textures and textiles of Ghanaian culture. There is a correlation between the invention of color photography and self-perception; in Ghana, Barnor represented Ghanaians for themselves, embodied and in vivid color. His subjects, no longer fashion models, are captured leaving church on Sunday, adjacent to a sports car; playing in the neighborhood or dancing during community festivals, thereby reflecting the various rhythms and speeds of Ghanaian society, from pose (fig. 21), to stillness (fig. 22), to frantic motion (fig. 23).

The Archives

Barnor worked in Accra for twenty-four years before moving back to London in the early ’90s. Despite his continuous work for over six decades, James Barnor had not attained the attention of a wider audience of curators, scholars or art institutions. The exhibition Mr Barnor’s Independence Diaries at Black Cultural Archives (BCA) in London in 2007, curated by Nana Oforiatta Ayim, was the first cohesive account of Barnor’s multifaceted work. The arts agency Autograph ABP curated his first retrospective James Barnor: Ever Young in 2010 and, in 2012, Barnor had his first public exhibition in Ghana.16For more information on Barnor’s exhibition history, see here The show James Barnor: A retrospective inaugurated the new building of the Nubuke Foundation in Accra in 2019, exploring the wide range of his photographic work in eight thematic directions: Family Affair, Governance and Order, Sports, Iconic, Muses, Community, Rhythm and Young at Heart, which was an important step in creating an initial overview of the multidimensionality of his work during the various chronopolitical and transcultural moments it traverses.

Thousands of negatives that are currently being scanned, indexed, and captioned by galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière in Paris, with Barnor’s assistance, will illuminate more untold stories and will constitute a complete record of his work, and by extension the history of Ghana, especially during the period 1970s–1980s that often goes overlooked in favor of focuses on earlier moments. A closer look in the archives reveals analogies to the studio photographs of Seydou Keïta or the portraits of J. D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere, while the duality between studio and street is comparable to the practice of Malick Sidibé and Sanlé Sory. The continuity and consistency of Barnor’s photographic work are reminiscent of the contribution of Ousmane Sembène’s œuvre to Senegalese cinema. Barnor’s photographic practice has followed the critical social shifts towards independence and testifies to the postcolonial realities of African states, the specificity of the Ghanaian context, as well as offering fresh views on the diasporic cultures of Britain. Producing vivid records of societal transformations, technological innovations, and geopolitical histories in the second half of the 20th century, Barnor has consistently insisted on a joyful and empowering present propelled by the people he depicts with tenderness, humor and trust.

- 1“This was especially visible with the backdrops imported from England. All photographers had their own backdrops and props, these would show affluence and a certain British influence.” James Barnor, James Barnor Ever Young, edited by Renée Mussai (Paris: éditions Clémentine de La Féronnière, 2015), 17.

- 2“The first photographers I remember were the police photographers: when there was an accident or crime scene, one particular police photographer would turn up and act as if he were the ruler of the whole scene […] He would control the entire place. So that caught my eye in the first place […] So photography was “in it”, in Ghana at the time when I grew up. […] Many of my relatives were photographers.” Ibid., 17.

- 3A permanent protagonist in Barnor’s pictures of the time is a porcelain figurine, which would become the trademark of his portraits until 1955 when one of Barnor’s children broke it. Ibid., 82, 85.

- 4Circulation of information has consistently been a challenge across African countries, and was especially marked between Anglophone and Francophone colonies. James Barnor says he did not know of the practices of Malian Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé or Nigerian J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere at the time. Although working at the same time and preoccupied with similar subject matter, Barnor he only became aware of these similar bodies of work later when they received broad international attention. Ibid., 18. See also this interview.

- 5The transition from the studio to the street was not uncommon for many West African photographers, including Malian Malick Sidibé, Nigerian J. D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere and Burkinabe Sanlé Sory. Ibid., 18.

- 6“I remember when Cecil King, who was the chairman of the Mirror group, came to Accra in 1950 with the idea of establishing a press. He already had a press group in Lagos, Nigeria and wanted to do something similar here. So he came with a team including McLellan, a veteran photographer from England, and they were looking for a photographer to start the paper. They were directed to my cousin Mr. Dodoo, who said, ‘I do not do this sort of work,’ but he sent his little boy to me. […] I didn’t expect then that I would be working for anybody and didn’t have a portfolio to show people. As he looked through my box of prints, he said ‘Not quite, but we will train you.’ I started working in September and the first paper came out in October 1950.” Ibid., 21.

- 7The rise of the new states gave rise to numerous official press agencies, such as AMAP in Mali, Congo Press in Congo-Kinshasa, Silly-Photo in Guinea, and ANTA in Madagascar. […] Drumfeatured work of some of the best black photographers. It was a vehicle that exerted subtle political pressure without jeopardizing its existence under draconian apartheid rule. It also recorded the vital cultural life of urbanized South Africans and thus promoted a positive expression of black urban resilience. Pierre-Laurent Sanner, Kelly Berman [eds], Eye Africa : African photography 1840-1998 (Cape Town: Eye Africa Project, 1998), 16.

- 8Barnor, Ever Young, 50.

- 9“For culture (from which the studium derives) is a contract arrived at between spectators and consumers. The studium is a kind of education (knowledge and civility, “politeness”) […] this second element which will disturb the studium I shall therefore call punctum: for punctum is also sting, speck, cut, little hole and also a cast of the dice”. Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida Reflections on Photography (New York : Hill and Wang, 1981), 27-28.

- 10“He had been a political prisoner detained by the British Colonial government but was freed after winning the seat in the general election for Accra Central contingency. I took two or three pictures, and for the rest of the month I was printing and selling them in the market and the streets of Accra”. The value placed on Nkrumah’s photograph testifies to the people’s desire for a leader who represented them, manifested by the purchase of his likeness to be positioned in their homes. Ibid., 55.

- 11“So we walked the streets of Accra. We finished up at the Old Polo ground, where the Nkrumah Mausoleum is now- right opposite Parliament House. From there Nkrumah and his people spoke to the crowd from a stage that was built. I remember Jim Bailey and I were standing right in the front. I took pictures of Nkrumah declaring, “Now Ghana is free”. Unfortunately I sent all those pictures away to South Africa for printing”. Ibid., 23.

- 12“My images were delayed and so they never made it to the papers”. Ibid., 57.

- 13Walther Collection, Events of the self : Portraiture and Social Identity, Contemporary African photography from The Walther Collection, ed. by Okwui Enwezor (Göttingen : Steidl, 2010), 26.

- 14Barnor, Ever Young, 28.

- 15“But I am always thinking of what I can do to help Ghana, because not many people had the opportunities that I had… I wanted to pass on some of my knowledge, which comparatively, was above a lot of photographers in Ghana.” A sense of longing for his native context is also evident in a quote describing when he visited Ghana with a friend from Europe: “I took him to our cocoa farm, and we visited the West African Cocoa Research Institute. He was there for four days, and on the second day he said ‘But James, why did you leave all of this to come to London?’ It still rings in my mind…” Ibid., 26-28.

- 16For more information on Barnor’s exhibition history, see here