Liubov’ Popova’s practice involved an active engagement with multiple movements and -isms in a relatively short period of time. In this essay, very formally distinct and different works by Popova, on view in the reinstalled galleries in 2019, are put into historical relation.

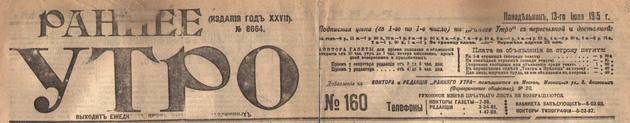

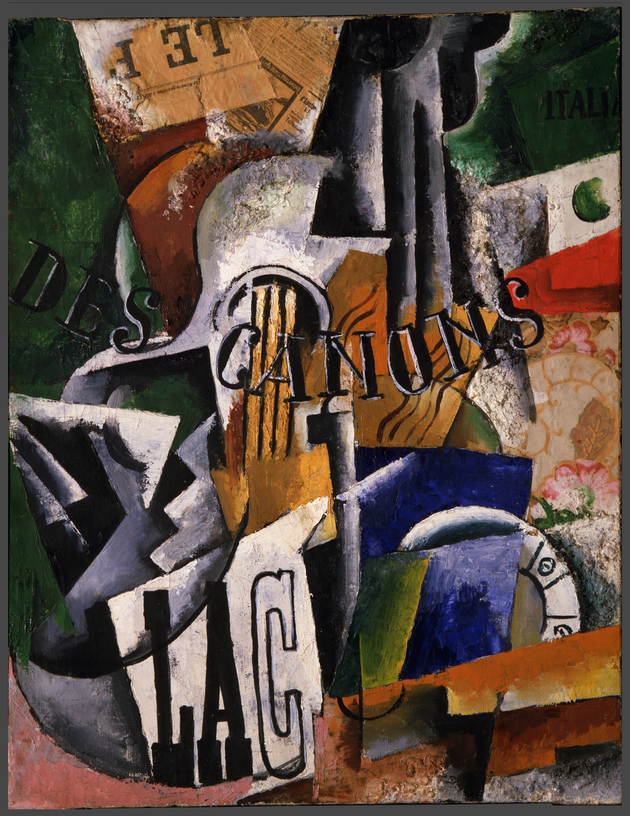

The title of Liubov’ Popova’s painting Objects from a Dyer’s Shop (Fig. 1) prompts the viewer to decipher the work’s imagery as a collection of fabrics, threads, and other objects, such as gloves and newspapers, piled on a table. The painting pays homage to both French Cubism and Italian Futurism and exemplifies a high point of Russian Cubo-Futurists’ absorption of both.1The term Cubo-Futurism was brought into circulation by Marcel Boulanger in October 1912 and was used by Italian critics in relation to the work of some of the French Cubists and Italian Futurists. It was most likely introduced into the Russian lexicon by the artist Alexandra Exter. Between 1912 and 1914, Exter spent a lot of time in Paris, where she lived with the Italian Futurist Ardengo Soffici in the same hostel as Popova and many other young Russian artists and served as a liaison between Russian, French, and Italian artists and critics. See Giovanni Lista, “Futurism and Cubo-Futurism,” Les Cahiers du MNAM no. 5 (September 1980): 458–459, and Georgii Kovalenko, “Alexandra Exter,” in Amazons of the Avant-Garde, eds. John Bowlt and Matthew Drutt (New York: Guggenheim, 2000), 133. In her autobiography, Popova distilled her artistic concerns: “The Cubist period (the problem of form) was followed by the Futurist period (the problem of movement and color).”2As quoted in Katalog posmertnoi vystavki khudozhnika konstruktora L.S. Popovoi (Moscow: VKhUTEMAS, 1924), 6. The painting’s still life—supplemented by isolated floating letters (П Е Р), a newspaper recognizable by its title and font (Rannee Utro [Early Morning]), (Fig. 2) and an illusionistic tassel—constitutes an overt tribute to Cubism. Yet what strikes the viewer most is not the work’s ostensible subject matter but rather its dense accumulation of shapes, colors, and textures that appear to be swirling in a shallow space. Sharp diagonal lines pierce the mass of colors and forms, structuring the work’s alternating volumetric and flat surfaces while contrasting with the painting’s curvilinear lines, such as the wide colored ribbons, enhanced by a strong chiaroscuro. The visual sense of overcrowding is further heightened by the bright and unnatural colors: blue, pink, orange, and, especially, yellow; the title’s explicit reference to a dyer’s shop—krasil’nia, also inscribed on the back of the stretcher—foregrounds Popova’s deliberate experimentation with color. Equally important is the play of disparate textures: one can guess the curly gray shapes might refer to woolen threads, but the brown fibers of the table subvert any resemblance to perceptible wood and highlight its material properties instead, in sync with the preoccupations of Popova’s fellow artist and studio neighbor, Vladimir Tatlin.3In 1913 and 1914, Tatlin was intensely interested in the properties of materials as such, seeking to convey them directly rather than illusionistically as Picasso and Braque had done. During this time Popova worked in Tatlin’s Moscow studio at Ostozhenka 37. Maria Gough has aptly analyzed Tatlin’s “materiological determinism” in “Faktura: The Making of the Russian Avant-Garde,” Res: Anthropology and aesthetics 36 (Autumn 1999): 32-59. Rather than dissecting the composition into formal elements, Popova actively constructed it. Densely populating a shallow space with swirling objects of varied textures, she gave dynamism to form, masterfully combining the findings of both Cubism and Futurism and beginning to develop her own pictorial idiom.

Popova was an avid learner, and her privileged background (she was born into a rich and educated merchant family highly interested in the arts) gave her an early and diversified exposure to the arts. By 1912, when she was 23, Popova had studied Old Master paintings and Italian Renaissance works at both the Hermitage Museum and at sites in Italy during a family trip there in 1910. Moreover, she had carefully examined medieval Russian paintings in situ while visiting a number of old Russian cities and had methodically studied the Post-Impressionists she thought most important: Paul Gauguin, Vincent Van Gogh and, especially, Paul Cézanne. Between December 1912 and May 1913, she immersed herself in the cosmopolitan Parisian avant-garde, studying with Henri Le Fauconnier and Jean Metzinger at L’Académie de La Palette and befriending numerous French, Russian, and Italian artists and critics. Back in Moscow, Popova fueled artistic exchange, working in shared studios alongside Tatlin, Nadezhda Udal’tsova, Aleksandr Vesnin, and other ambitious vanguard artists. (Fig. 3) In March 1914 she returned to Paris and travelled on to Italy, together with her sculptor friends Vera Mukhina and Iza Burmeister. There they studied the Italian Renaissance and absorbed the advances of the Italian Futurists, visiting 15 cities before the outbreak of World War I.4Mukhina recalled that in Popova’s study of classical art in Italy, she was especially focused on the issue of color. See P. K. Suzdalev, Vera Mukhina (Moscow: Izobrazitel’noe Iskusstvo, 1971), 85. The use of autonomous color was also of primary interest to Popova in medieval Russian painting.

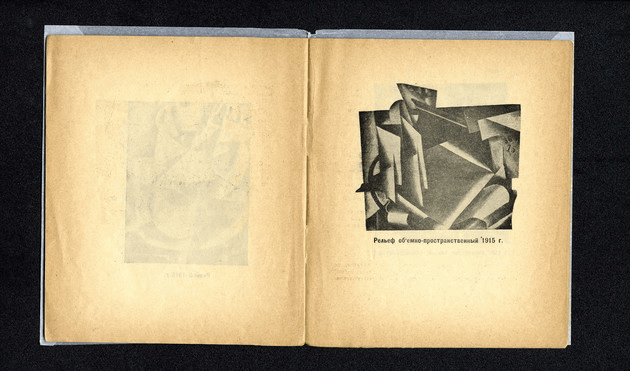

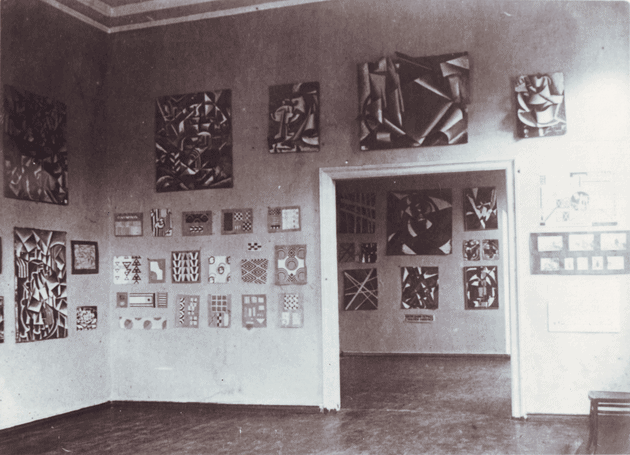

Popova first exhibited Objects from a Dyer’s Shop at the First Futurist Exhibition of Paintings Tramvay V in Petrograd in March 1915. The painting was listed in the exhibition catalogue as Object from a Dyer’s Shop and was preceded by another Popova work entitled simply Object (Predmet). The painting’s next known showing was at Popova’s posthumous exhibition of 1924, now titled plurally Objects from a Dyer’s Shop (Predmety iz Krasil’ni) and followed by a sketch for it (now lost) in the catalogue. The painting is visible in the installation photo alongside a number of formally similar works. (Fig. 4) (Two visually comparable examples among her preserved works are Italian Still Life (Fig. 5) and Objects (Fig. 6).) Tramvay V was an important turning point in the history of the Russian avant-garde: there Tatlin showed his first abstract reliefs, while Malevich exhibited paintings he called “alogical” and accompanied them with a handwritten sign on the wall that read “the content of the works is unknown to the author.” Tatlin and Malevich were then on the brink of abstraction, which they would present on a large scale at the famous Last Exhibition of Futurist Paintings 0.10 in December 1915.5Interestingly, only eight months passed between the “first” and “last” Futurist exhibitions of paintings.

While Objects in a Dyer’s Shop shows Popova as a diligent student of European avant-gardes, it also reveals the rigor of her pictorial practice that soon led her to create her own distinct abstract visual language. As she described it, “The principle of abstracting parts of an object led, by logical necessity, to the abstraction of the object itself—this is the path to nonobjectivity. The problem of representation is replaced by the problem of construction of form and lines (post-Cubism) and of color (Suprematism).”6As quoted in Katalog posmertnoi vystavki, 6. Popova’s precise articulation of the inner logic of her artistic evolution revealed the complementarity of the methods developed by Malevich and Tatlin, which were polarized by their rivalry into Suprematism and “Tatlinism.” Popova’s next step was to take her keen sense of faktura7A key term in the history of the Russian avant-garde, faktura comes from the Latin facere (to make) and refers to the ways in which a work of art has been made—specifically, how its material constituents have been worked. See Gough, “Faktura,” 33. and color into three dimensions. In 1915, she made an abstract Volumetric-spatial Relief (Ob’emno-prostranstvennyi Rel’ef) (Figs. 7-8), and at the 0.10 exhibition she showed works subtitled “plastic painting” (plasticheskaia zhivopis’). These works integrated a sensibility to faktura and space with a keen sense of color and pictorial planarity.

Through a gradual process of abstracting from objects and focusing on the construction of an integrated pictorial form, Popova developed a unique and compelling abstract idiom, which reached its peak in her series Painterly Architectonics (Zhivopisnaia Arkhitektonika) (1916–19) (Fig. 9) and Spatial-Force Constructions (Prostranstvenno-Silovyie Postroeniia) (1920–21). (Fig. 10) Just as she wove together the principles of Cubism and Futurism from 1912 to 1915, later that decade she successfully synthesized the essential attributes of Suprematism and Tatlinism—their focus on color and plane, materiality and faktura—thus exposing the formal commonalities between these important trends. Always valuing artistic exchange, Popova worked closely with Tatlin from 1913 to 1914, then with Malevich and his group of Suprematists during 1916 and 1917, and then joined the emerging group of Constructivists at GINKhUK (the State Institute of Artistic Culture) from 1920 to 1921. She went on to pioneer Constructivist theater design with Vsevolod Meyerhold and, finally, moved into production before her sudden death from scarlet fever in 1924. Her artistic path was in tune with the most vanguard ideas of her contemporaries, while also being confidently independent.

- 1The term Cubo-Futurism was brought into circulation by Marcel Boulanger in October 1912 and was used by Italian critics in relation to the work of some of the French Cubists and Italian Futurists. It was most likely introduced into the Russian lexicon by the artist Alexandra Exter. Between 1912 and 1914, Exter spent a lot of time in Paris, where she lived with the Italian Futurist Ardengo Soffici in the same hostel as Popova and many other young Russian artists and served as a liaison between Russian, French, and Italian artists and critics. See Giovanni Lista, “Futurism and Cubo-Futurism,” Les Cahiers du MNAM no. 5 (September 1980): 458–459, and Georgii Kovalenko, “Alexandra Exter,” in Amazons of the Avant-Garde, eds. John Bowlt and Matthew Drutt (New York: Guggenheim, 2000), 133.

- 2As quoted in Katalog posmertnoi vystavki khudozhnika konstruktora L.S. Popovoi (Moscow: VKhUTEMAS, 1924), 6.

- 3In 1913 and 1914, Tatlin was intensely interested in the properties of materials as such, seeking to convey them directly rather than illusionistically as Picasso and Braque had done. During this time Popova worked in Tatlin’s Moscow studio at Ostozhenka 37. Maria Gough has aptly analyzed Tatlin’s “materiological determinism” in “Faktura: The Making of the Russian Avant-Garde,” Res: Anthropology and aesthetics 36 (Autumn 1999): 32-59.

- 4Mukhina recalled that in Popova’s study of classical art in Italy, she was especially focused on the issue of color. See P. K. Suzdalev, Vera Mukhina (Moscow: Izobrazitel’noe Iskusstvo, 1971), 85. The use of autonomous color was also of primary interest to Popova in medieval Russian painting.

- 5Interestingly, only eight months passed between the “first” and “last” Futurist exhibitions of paintings.

- 6As quoted in Katalog posmertnoi vystavki, 6.

- 7A key term in the history of the Russian avant-garde, faktura comes from the Latin facere (to make) and refers to the ways in which a work of art has been made—specifically, how its material constituents have been worked. See Gough, “Faktura,” 33.