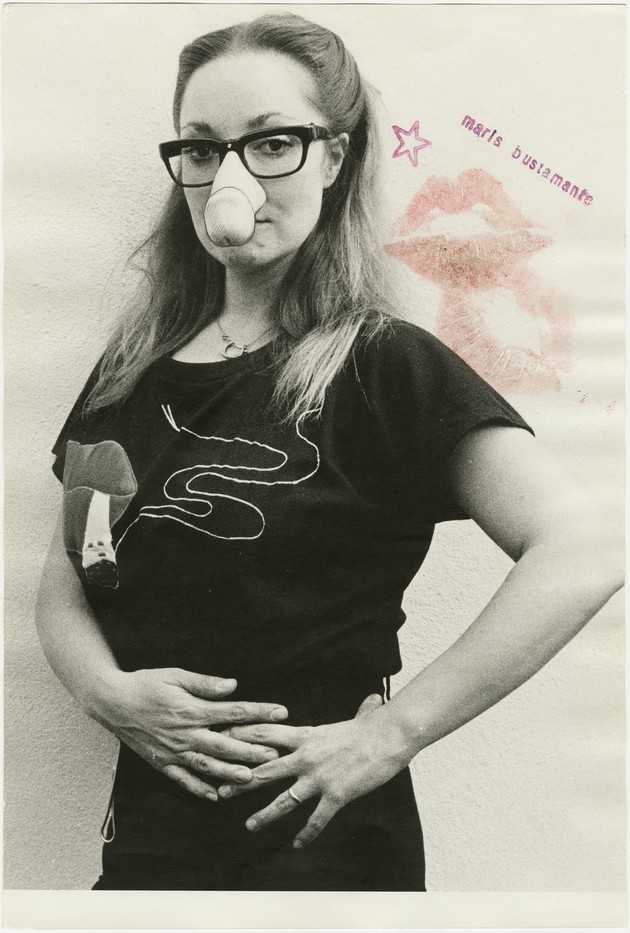

Created in 1982 by the Mexican conceptual artist Maris Bustamante, El pene como instrumento de trabajo/para quitarle a Freud lo macho (The Penis as a Work Instrument)/To Get Rid of the Macho in Freud) is an iconic work for the history of both performance art and feminist art in Mexico. By contextualizing the piece in relation to Bustamante’s practice as a member of the No-Grupo collective and later as part of the feminist group Polvo de Gallina Negra, we can understand its pivotal role in the emergence of feminist content in the artist’s production and in feminist art in general.

Bustamante received her initial training as an artist at the Escuela Nacional de Pintura, Escultura y Grabado “La Esmeralda” in the 1970s, and after early explorations in various media, her work became focused on conceptual and performance art.1Dina Comisarenco Mirkin, Eclipse de siete lunas: Mujeres muralistas en México (Mexico City: Artes de México, 2017), 188–190. She also worked as a professor and researcher at the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana beginning in the 1970s, concentrating on the transdisciplinary art forms she defined as Formas PIAS (performances, installations, and atmospheres).2Maris Bustamante, “‘Formas Pías’: Cartografías incompletas en la obra de Juan Acha,” post, September 28, 2017, https://post.at.moma.org/content_items/1042-formas-pias-cartografias-incompletas-en-la-obra-de-juan-acha.

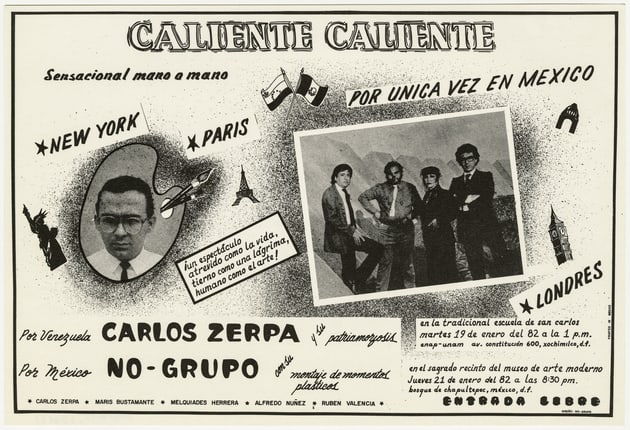

Bustamante came of age as an artist during a period that was characterized by the formation of interdisciplinary conceptual groups known as “Los Grupos,” and she was a key member of the No-Grupo, active from 1977 to 1983, with Rubén Valencia, Melquiades Herrera, and Alfredo Nuñez.3For more information about No-Grupo and its participants, see Sol Henaro, No-Grupo: Un zangoloteo al corsé artístico (Mexico City: Museo de Arte Moderno/Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, 2011), 18–21. In close dialogue with ideas about non-objectualist art expounded by the Peruvian-born critic and theorist Juan Acha, the group staged ephemeral actions in public spaces that Bustamante baptized as Montajes de Momentos Plásticos.4Henaro indicates that while Carla Stellweg, who worked at the Museo de Arte Moderno at the time, familiarized the group with the term “performance,” they preferred the nomenclature in Spanish formulated by Bustamante (No-Grupo, 23). These were characterized by the appropriation, activation, and resignification of everyday objects, language, and social situations in a kind of guerrilla action that sought to interrupt and subvert habitual codes of representation and the conventional structures and power relations of the art world and market.5Mara Polgovsky Ezcurra, Touched Bodies: The Performative Turn in Latin American Art (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2019), 172–173. Consonant with this practice, the announcements the group created for their activities used the formats and styles of publicity for popular urban events like lucha libre (Fig. 3).

Marked by the Mexican government’s violent repression of dissidence in the decades following the Tlatelolco massacre of 1968, No-Grupo’s actions presented a break with official institutions and hierarchies. They questioned dogmas and opened up spaces for critical reflection.6Polgovsky, Touched Bodies, 162–165. Also, unlike more group-minded collectives of the period, No-Grupo’s members created individual actions related to a general theme, maintaining their autonomy within a collaborative structure (an element underlined by the name of the collective).7Henaro, No-Grupo, 24. In this context, Bustamante carried out conceptual actions that constituted a sort of “Theatre of the Absurd,” highlighting key contradictions regarding power, property, and gender. The role of sexual symbolism was often underlined in these operations.

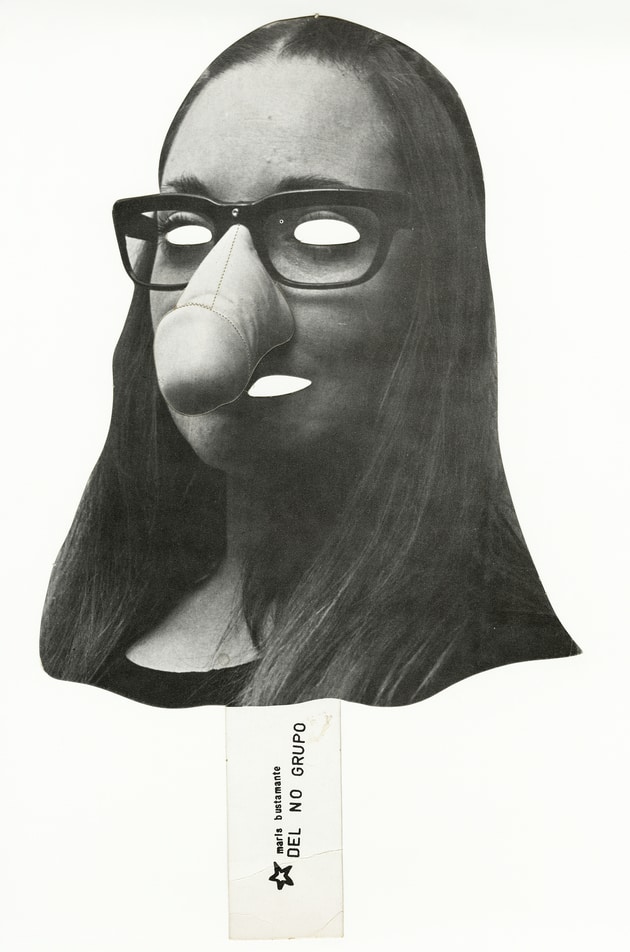

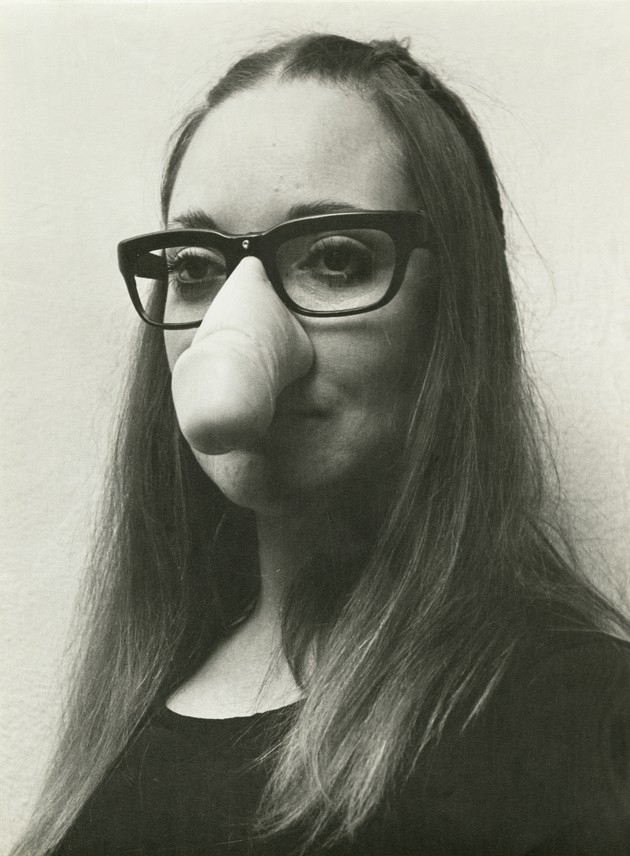

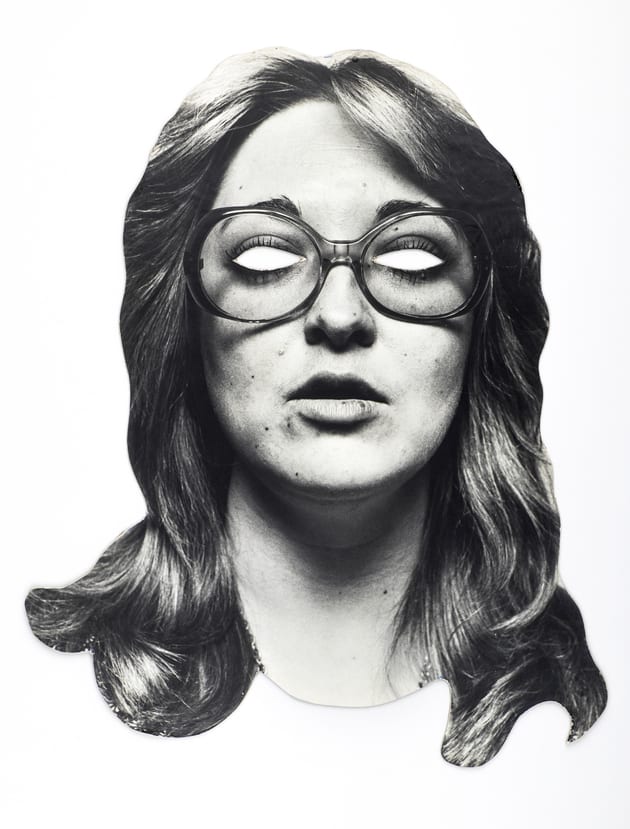

El pene como instrumento de trabajo/para quitarle a Freud lo macho was Bustamante’s personal contribution to the No-Grupo performance Caliente-Caliente (mano a mano con Carlos Zerpa)8Zerpa, a Venezuelan artist known primarily as a painter, was also active as a performance artist in the early 1980s and was close to No-Grupo. The performance Caliente-Caliente was organized on the occasion of his first presentation in this mode in Mexico. See “El pene como instrumento de trabajo,” Archivo Virtual Artes Escénicas, accessed June 25, 2019, artesescenicas.uclm.es/index.php?sec=obras&id=1139. [Hot-Hot (Hand in Hand with Carlos Zerpa)] that took place at the Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico City in January 1982 (Fig. 4). Bustamante manufactured 300 cardboard masks of her own face, replacing the nose on each with a phallus identified by a tag as a “work instrument,” and distributed them to the audience as a response “to Sigmund Freud’s theory that a woman who wanted to engage in professional endeavors suffered from penis envy.”9See Bustamante’s description of the work at http://www.reactfeminism.org/entry.php?l=lb&id=24&e=a&v=&a=Maris%20Bustamante&t=, accessed June 25, 2019. Like many of Bustamante’s works of the period, the action mobilized a concise, ironic gesture through her performing body and its interaction with the public in order to counter social and theoretical mystifications that are used to justify and institutionalize hierarchy and discrimination.

The pose adopted by Bustamante for the photographic mask and the documentation of the piece (Fig. 5) conjures Mona Lisa as crossed with Groucho Marx. Hinges on the mask’s “nose” and eyes allowed the faux penis to become erect and the eyelids to open. With the mask on, Bustamante intoned a Spanish translation of the lyrics to a song by punk artist Nina Hagen that played in the background (the lyrics expressed Hagen’s sardonic desire to be a man because men were allowed to have more fun).10Archivo Virtual Artes Escénicas, accessed June 25, 2019, artesescenicas.uclm.es/index.php?sec=obras&id=1139. Overall, the piece humorously debunked the phallocratic division of labor by suggesting that anyone could put on and take off the very attribute that permitted access to certain social roles and activities, thus upending the patriarchy by reducing its talismanic object to the realm of the everyday. There was also an element of the burlesque to the performance (a theme Bustamante would take up again in Pornochou of 1984 to 1985).

Bustamante’s use of a mask underlined an important political strategy of No-Grupo’s. As noted in the exhibition catalogue Perder la forma humana: Una imagen sísmica de los años ochenta en América Latina, “the mask as conceived by Bakhtin is a ‘negation of identity and fixed meaning,’ an ‘expression of transferences’….The mask acts as a kind of catalyst: it not only covers the face, but also with that same gesture reveals different aspects of the social body.”11Fernanda Nogueira, Lía Colombino, Sol Henaro, Ana Longoni and Paulina Varas, “Máscaras” in Red Conceptualismos del Sur, Perder la forma humana: Una imagen sísmica de los años ochenta en América Latina (Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 2012), 186. Indeed, the mask as a discursive vehicle had been present in No-Grupo’s work since their action for the 10th Paris Biennial in 1977, held at the Centre Georges Pompidou. They did not attend physically, but sent cardboard masks based on photographs of their faces for the public to wear in accordance with the collective’s instructions (Fig. 6). “Our proposition induces the possibility that the spectator be the one who facilitates our virtual presence,” the group declared. “We want to be there without being there physically; we want the viewer to be the one who takes us there; we want to inhabit the visage of each person who puts on our masks; we want to be the spectator.”12The typewritten text is reproduced in Henaro, No-Grupo, 38. Their intervention suggested a merging of identities, a displacement of the self and an inhabiting of the other—a psychological and social exercise presented in a neobaroque mode.

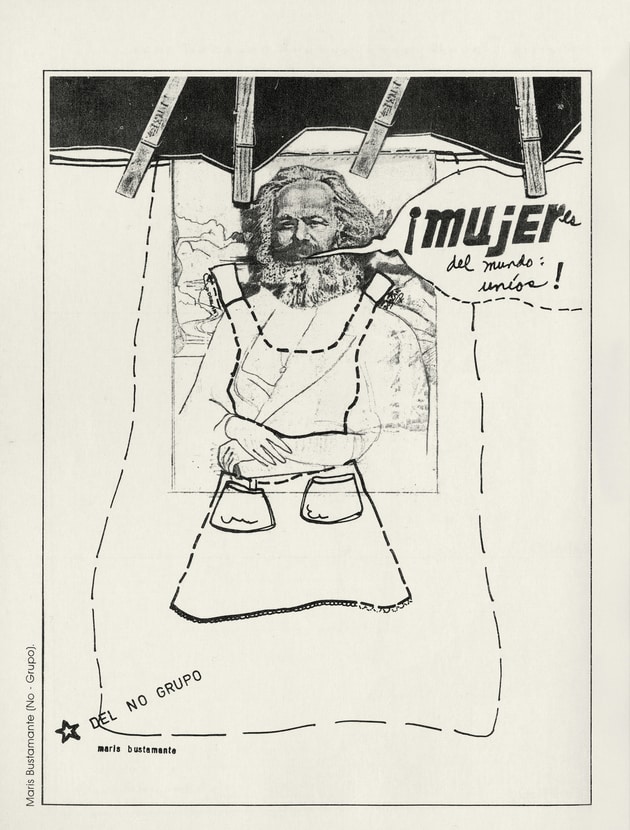

The feminist bent in Bustamante’s work that emerged in El pene como instrumento de trabajo was undoubtedly linked to the increasing influence of the feminist movement in Mexico in that moment13For more information on this topic, see Nora Nínive García, Márgara Millán, and Cynthia Pech, eds., Cartografías del feminismo mexicano, 1970–2000 (Mexico City: Universidad Autónoma de la Ciudad de México, 2007). and was expanded in her contribution to Agenda Colombia 83, a graphic diary produced by No-Grupo in 1982 in collaboration with the Colombian insurgent group M-19 and the Mexican art collectives Proceso Pentágono and Grupo Mira, among others (Fig. 7).14Henaro, No-Grupo, 89. In this work, she presented herself with her visage displaced by that of Karl Marx (who became her “mask”), and introduced additional elements to her performative identity and feminist iconography that would be consolidated the following year when she and Mónica Mayer, another pioneering Mexican feminist artist, formed the first feminist art group in Mexico: Polvo de Gallina Negra (Black Hen Powder) (Fig. 8).15The group’s name comes from a powder sold in traditional Mexican markets to protect people from the evil eye, a quality that seemed appropriate to Mayer and Bustamante given the precarious situation of art in Mexico at the time, especially for women and feminist artists. For more details, see Sol Henaro, et al., Mónica Mayer. Si tiene dudas… pregunte: Una exposición retrocolectiva/When In Doubt… Ask: A Retrocollective Exhibit (Mexico City: MUAC-UNAM, Alumnos 47, and Editorial RM, 2016), 60.

Bustamante’s image in Agenda Colombia 83 shows what seems to be a cloth hung on a clothesline, on which is traced a rectangular form suggesting both a sewing pattern and a notebook page. Within it is another sketch of a more conventional landscape, which serves as a background to a portrait that once again echoes the Mona Lisa. In this meta-image, the artist’s hands are demurely folded in front of her lower torso (an anatomical area that would later be emphasized by Polvo de Gallina Negra as the defining zone of motherhood) and her body, scored with a few lines alluding to a brassiere, is covered by an apron, represented with the dashed lines of a sewing pattern and with tabs to affix it to the body as if it were a paper-doll costume. All these aspects refer to the imposition of gendered stereotypes on women in various contexts—dress, play, and artistic representation, to name a few—but the artist’s head is replaced by a photograph of Marx’s face, from which emerges a speech bubble containing the appropriated, modified slogan “¡Mujeres del mundo: uníos!” (Women of the World: Unite!). “Mujer” is rendered in a bold graphic font, intimating a masculinist command, but it is interpolated with a handwritten script that holds the rest of the statement (“-es del mundo: uníos”). Altogether, Bustamante transmuted a directive both patriarchal and Communist into a feminist motto.

Moreover, the apron foreshadows those that would become the hallmark of Polvo de Gallina Negra, acting both as a reference to women’s identification in relation to domestic activities and as a prop that set off both the real and simulated pregnant bodies of the group’s two members in the performative activities of their project ¡MADRES! (1983–90).16¡MADRES! was conceived as a way to integrate the art and life of its participants at a time when both had small children. It included various elements, among them performances, actions, and mail art. ¡MADRES! also included a series of performances for television, including one in 1987 for the program Nuestro Mundo in which they invited host Guillermo Ochoa to put on a Styrofoam belly and named him “Mother for a Day.” See Henaro, et al., Mónica Mayer, 61. The contrast between the submissive hand gesture and the vehement rhetoric in her piece for Agenda Colombia 83 was characteristic of No-Grupo’s artistic strategy—highlighting ironic contradictions to underline pointed social messages—but the work also launched a new performative persona for Bustamante that she would embody for the next 10 years—a direction signaled by the movement of her own body out of the picture frame and into a feminist framing device. In this respect, El pene como instrumento de trabajo/para quitarle a Freud lo macho can be understood not only as a powerful conceptual statement in its own right, but also as one that articulated and enacted a decisive repositioning of Bustamante’s practice overall in relation to issues of gender.

All title translations in this text by the author.

- 1Dina Comisarenco Mirkin, Eclipse de siete lunas: Mujeres muralistas en México (Mexico City: Artes de México, 2017), 188–190.

- 2Maris Bustamante, “‘Formas Pías’: Cartografías incompletas en la obra de Juan Acha,” post, September 28, 2017, https://post.at.moma.org/content_items/1042-formas-pias-cartografias-incompletas-en-la-obra-de-juan-acha.

- 3For more information about No-Grupo and its participants, see Sol Henaro, No-Grupo: Un zangoloteo al corsé artístico (Mexico City: Museo de Arte Moderno/Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, 2011), 18–21.

- 4Henaro indicates that while Carla Stellweg, who worked at the Museo de Arte Moderno at the time, familiarized the group with the term “performance,” they preferred the nomenclature in Spanish formulated by Bustamante (No-Grupo, 23).

- 5Mara Polgovsky Ezcurra, Touched Bodies: The Performative Turn in Latin American Art (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2019), 172–173.

- 6Polgovsky, Touched Bodies, 162–165.

- 7Henaro, No-Grupo, 24.

- 8Zerpa, a Venezuelan artist known primarily as a painter, was also active as a performance artist in the early 1980s and was close to No-Grupo. The performance Caliente-Caliente was organized on the occasion of his first presentation in this mode in Mexico. See “El pene como instrumento de trabajo,” Archivo Virtual Artes Escénicas, accessed June 25, 2019, artesescenicas.uclm.es/index.php?sec=obras&id=1139.

- 9See Bustamante’s description of the work at http://www.reactfeminism.org/entry.php?l=lb&id=24&e=a&v=&a=Maris%20Bustamante&t=, accessed June 25, 2019.

- 10Archivo Virtual Artes Escénicas, accessed June 25, 2019, artesescenicas.uclm.es/index.php?sec=obras&id=1139.

- 11Fernanda Nogueira, Lía Colombino, Sol Henaro, Ana Longoni and Paulina Varas, “Máscaras” in Red Conceptualismos del Sur, Perder la forma humana: Una imagen sísmica de los años ochenta en América Latina (Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 2012), 186.

- 12The typewritten text is reproduced in Henaro, No-Grupo, 38.

- 13For more information on this topic, see Nora Nínive García, Márgara Millán, and Cynthia Pech, eds., Cartografías del feminismo mexicano, 1970–2000 (Mexico City: Universidad Autónoma de la Ciudad de México, 2007).

- 14Henaro, No-Grupo, 89.

- 15The group’s name comes from a powder sold in traditional Mexican markets to protect people from the evil eye, a quality that seemed appropriate to Mayer and Bustamante given the precarious situation of art in Mexico at the time, especially for women and feminist artists. For more details, see Sol Henaro, et al., Mónica Mayer. Si tiene dudas… pregunte: Una exposición retrocolectiva/When In Doubt… Ask: A Retrocollective Exhibit (Mexico City: MUAC-UNAM, Alumnos 47, and Editorial RM, 2016), 60.

- 16¡MADRES! was conceived as a way to integrate the art and life of its participants at a time when both had small children. It included various elements, among them performances, actions, and mail art. ¡MADRES! also included a series of performances for television, including one in 1987 for the program Nuestro Mundo in which they invited host Guillermo Ochoa to put on a Styrofoam belly and named him “Mother for a Day.” See Henaro, et al., Mónica Mayer, 61.