Art historian Adomas Narkevičius brings together Baltic artists Anu Põder and Virgilijus Šonta, considering their mutual interest in human corporeality and non-heteronormative visuality to explore how their artwork reflects a disregard of official concerns of the late Soviet era, challenges the persistent art historical narratives of “belatedness” and “uniformity” of the former Socialist bloc, and sheds light on the blind spots of the homogenizing use of Western theoretical frameworks.

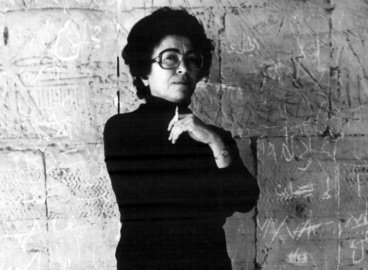

Current affairs perpetually extort blackmail from the artist who takes no notice of their urgency, who elects to dwell with the issues that the making of the artwork engender. In the context of the late Soviet era in the Baltics, Estonian artist Anu Põder (1947–2013) and Lithuanian photographer Virgilijus Šonta (1952–1992) disregarded the demands of their time—whether the concerns of their individual artistic milieus or ideological pressures. Three decades into the independence of the Baltic states, Põder’s ephemeral, corporeal sculptures and Šonta’s homoerotic photographs have only lately been reconsidered.1For Anu Põder, this includes Be Fragile! Be Brave!, a major retrospective in Tallinn’s Kumu Art Museum in 2017, which led to the acquisition of the majority of the artist’s previously uncollected works by the National Art Museum of Estonia. International exposure has followed—firstly, in the 13th Baltic Triennial (2018), and most recently, in the Liverpool Biennial of Contemporary Art (2021) and Tate Modern, which has acquired work by the artist. Incidentally, since I began my research into the intimate part of Virgilijus Šonta photographic archive in spring 2020, Lithuanian National Broadcaster (LRT) has published the following: Mindaugas Klusas, “Homoseksualumą ilgai neigęs fotografas Šonta su savimi susitaikė tik prieš kraupią baigtį,” December 6, 2020, https://www.lrt.lt/naujienos/kultura/12/1290350/homoseksualuma-ilgai-neiges-fotografas-sonta-su-savimi-susitaike-tik-pries-kraupia-baigti; and “Homoseksualaus fotografo Virgilijaus Šontos meilė ir žūtis: prabyla mylimasis, įtariamasis, anonimas,” February 14, 2021, https://www.lrt.lt/naujienos/kultura/12/1341609/homoseksualaus-fotografo-virgilijaus-sontos-meile-ir-zutis-prabyla-mylimasis-itariamasis-anonimas. Likewise, the first exhibition of these previously unpublished homoerotic auto-fictional photographs was held in September 2020 at The Naked Room, a gallery in Kiev, Ukraine. The corporeality of both is a call to the senses, a reminder that the perceiving mind is also a desiring body. Considering this, what does dwelling with these particular forms of knowledge originating under Soviet rule (and these artworks are exactly that) offer? How can it give meaning to what is otherwise opaque, and more broadly, what can postwar art history learn by writing from the vantage point of the Baltics—by keeping the region’s perspective fully in mind, as opposed to an afterthought—in new scholarship?

The case of visual art in the Baltic region during the Soviet decades is a peculiar one. First annexed in 1940 and subsequently incorporated as Western provinces of the USSR in 1944, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia did not reconstruct entire histories of neo-avant-garde gestures or feminist and queer art practices—unlike many former socialist “satellite” states in “Central East” Europe. The comparatively tighter grip imposed by the central apparatus on information dissemination, communication, and travel in effect led to the specificity of the Baltic art context under state communism. After the Stalinist period, government policies paved the way for the emergence of less resolvable gray zones between Baltic political and artistic spheres.2Klara Kemp-Welch, Networking the Bloc: Experimental Art in Eastern Europe, 1965–1981 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2019), 365–66. These incentivized pursuit of a quasi-modernist form with socialist subject matter, relative freedom in terms of artistic experimentation under the banner of applied arts, relative visibility on the margins of what was deemed official art, and even contact, albeit restricted, with artists working in Western Europe and the United States.3See ibid. See also Arūnas Streikus, “What Made Modernism So Quiet? The Particularities of the Art Field in the Soviet West,” Acta Academiae Artium Vilnensis 95 (2019): 14–28; and Erika Grigoravičienė, “Modernisation, (Post)Modernities, and New Modernism: The Concepts of Lithuanian Art History Starting from the Late 1950s,” ibid., 53–85. Recent art historical research exploring these developments disentangles the deceptive uniformity of “Central East” Europe, and moves beyond the model of “total suppression of artistic freedom,” itself a totalizing reading of late Soviet culture.4For “the regime against the dissident” art historical model, see Alla Rosenfeld and Norton D. Dodge, eds., Art of the Baltics: The Struggle for Freedom of Artistic Expression Under the Soviets, 1945–1991 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; Rutgers, NJ: Jan Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, State University of New Jersey, 2002), 3.

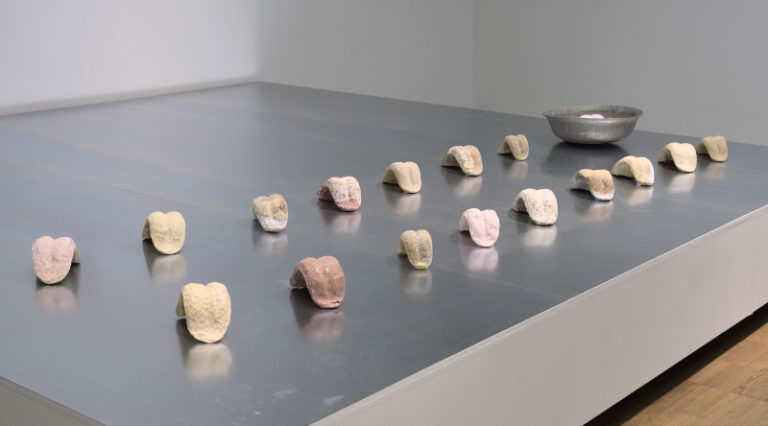

In the masculine “Bronze Age” of Estonian sculpture, many of Anu Põder’s peers were concerned with the timeless preservation of their work at the same time they were producing grotesque figuration that challenged the orthodox socialist realism. Põder instead opted to use “soft” materials and techniques prone to decay.5Rebeka Põldsam, “Anu Põder. Be Fragile! Be Brave!,” in Anu Põder. Be Fragile! Be Brave!, ed. Rebeka Põldsam, exh. cat. (Tallinn: Kumu Art Museum, 2017), 11. She recalled later, “As a small woman I could not lift stones or heavy scaffolding, and then while raising my children, I began using these lighter materials.”6Anu Põder, video interview by Isabel Aaso-Zahradnikova and Juta Kivimäe for the archives of the Art Museum of Estonia, 2007, Estonian National Museum, Tallinn. This was likely the more strenuous route as women artists who cast in metal would likely have received support from studio technical staff—as was common at the time.7Eha Komissarov, “Three Stories about the Work of Anu Põder,” in Anu Põder. Be Fragile! Be Brave!, 50. In the 1990s, uninterested in the newly encouraged national posturing, Põder continued undertaking personal, quietly defiant sculpture (figs. 1–3).8Põldsam, “Anu Põder. Be Fragile! Be Brave!,” 19. The artist’s preference for relatively perishable materials, for fabric, wax, plaster, soap, glue, and plastic—which was considered a shortcoming prior to the onset of installation art,9See Komissarov, “Three Stories about the Work of Anu Põder,” 44; and “Jaan Elken Interviews Anu Põder, 2008,” in Anu Põder, ed. Reet Varblane (Tallinn: Tallinna Kunstihoone Fond, 2009), 45. points to something more immediate than the high modernist ideal of autonomous authorship (figs. 4–7). Opting for an intimate, material art-making process, the artist—phenomenologically and politically—worked with and through the needs and capabilities of her own body. That is, she used soft materials to suggest the human-like corporeality of her sculptures, and at the same time, worked in full appreciation of the capabilities and limitations of her own body with regard to the choice of medium.

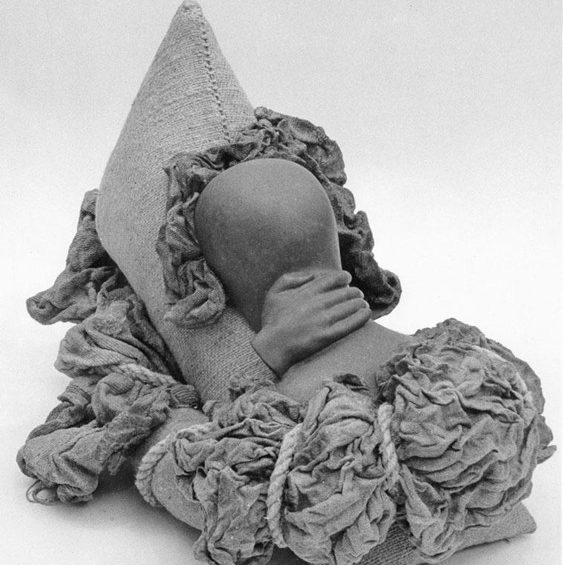

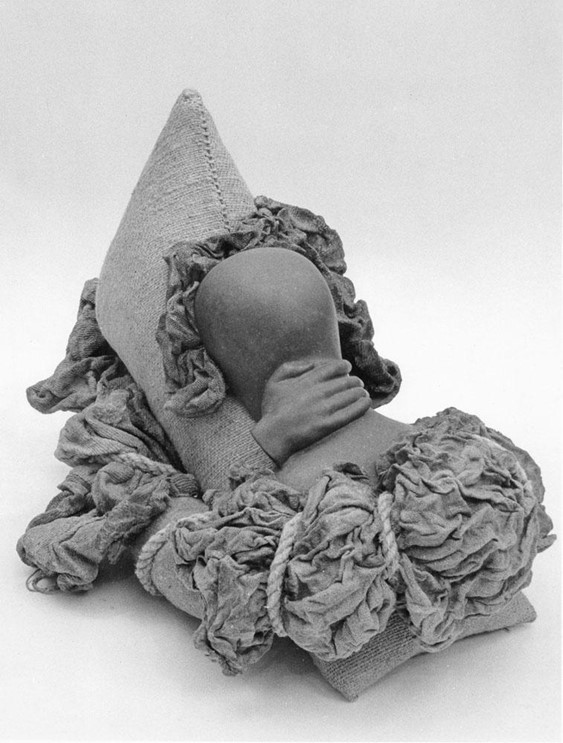

Põder’s sculpture Very Old Memories (1985; figs. 8–10)—caught between the figural and the formless—revels in the suspension of becoming.10Yve Alain Bois and Rosalind Krauss, Formless: A User’s Guide (New York: Zone Books; Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1997), 18. A burlap sack reclines as if a chaise longue for another body, which appears in the fragmented form of a mannequin’s head. Textiles and ropes entwine the two, the weight of the plastic head rendering the burlap a means of support. The material and formal decisions imply this asymmetrical relationship even before the “passive” burlap shape is made recognizable as a human body. This nestling quality often leads to the work being understood as the first of Põder’s “embrace” sculptures—or the first to suggest a physical bond between two bodies that is colored by affection,11Põldsam, “Anu Põder. Be Fragile! Be Brave!,” 13. that can be read variously as coitus or a maternal embrace.12See Põldsam, “Anu Põder. Be Fragile! Be Brave!”; and Komissarov, “Three Stories about the Work of Anu Põder.” However, taking the artwork’s partial formlessness back into the sphere of representation denies its implicit political gesture. The representational reading assumes gender, and attaches it to normative roles—such as maternal care or missionary sex—offering a fixed, binary resolution that the artwork resists at every turn. Very Old Memories provokes the viewer to act as a voyeur, to attempt to determine the origin of the scene, and to make sense of the relations within. To the observing eye, it suggests bodies resting and caressing, yet at the same time, clinging and violently grabbing. Here, memories (plural) and forms of memory—imagined, reconstructed and, perhaps, lived—play out. In thinking about what the artwork “contains,” one finds that it reveals itself as an overdetermined object in the psychoanalytic sense, as the visible effect of multiple likely causes.13Georges Didi-Huberman, Confronting Images: Questioning the Ends of a Certain History of Art (University Park: Penn State University Press, 2009), 179. The structure of the artwork plays with the assumption that it contains some genuinely lived mental content when instead, it “hosts” multiple incompatible psychological phenomena and states as it refracts them through the viewing subject’s own experience. The art object fictionalizes the “contained stuff” to show the complexity of human psychology—and to protect the life “facts” of the artist.

The sculpture relishes its polymorphous potential. In various iterations of the work (figs. 9, 10), its textile “orifices” are never consistently formed or located. The ever-changing placement of their folds perpetually shifts the relationship between the two “bodies.” Furthermore, the folds act as boundaries—as spaces that belong to neither entity. The beige hues blur them further, making it no longer obvious which “body” needs the other more.

Very Old Memories plays with the viewer’s desire to define the forms as two distinct and gendered human bodies. Outwitting its scopic regime, the work reflects back this gaze. In terms of gender identity, roles, and their asymmetrical dynamics through matter, the artwork puts the viewer in unpleasant proximity to their own need to define what they see in binaries. The (heteronormative) pasts marked by the sculpture haunt the (heteronormative) present and suggest a possible nonbinary future. This is how the work splits and weaves time. Likewise, the polymorphous politics of its form and materiality intimate the malleability of one’s own embodiment, the transience of gender identification, and the fleeting inverse of gender roles and interdependencies that follow. This is the vibrant future register of Põder’s work’s untimeliness.

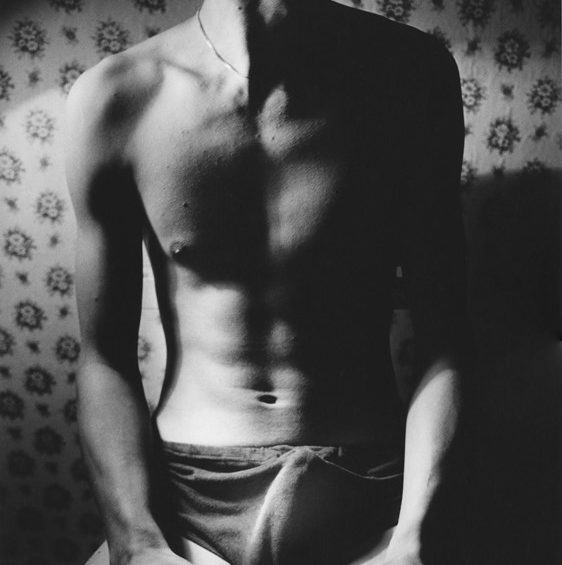

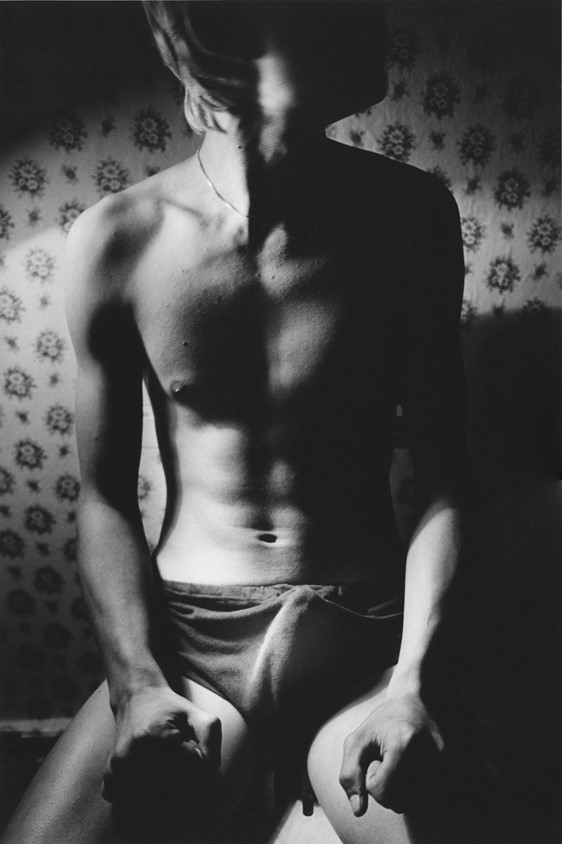

Virgilijus Šonta’s photographic archive holds at least thirty to forty photographs that diverge from his well-known humanist subject matter and aesthetic concerns, and that have faced uncomfortable silence (art) historically. Moreover, this silence has been sustained by the seclusion of the archive: until 2020, few of its photographs have circulated in the public eye through posthumous exhibitions and publications. Its more intimate content sets up a structure of homoerotic desire throughout the space of the Soviet Union in the depiction of a private cruising community of men, to which Šonta himself belonged, in a period when homosexual “acts” were criminalized (figs 11–14). The images not only depict homoerotic content but also function as carriers of homoerotic desire through time—the desire of those photographed, of the photographer himself, and of viewers many years later. They set up psychosomatic encounters between the bodies of those within the images and those outside of them. As such, these photographs continue to linger on the cusp of visibility, in the unconscious of the present.

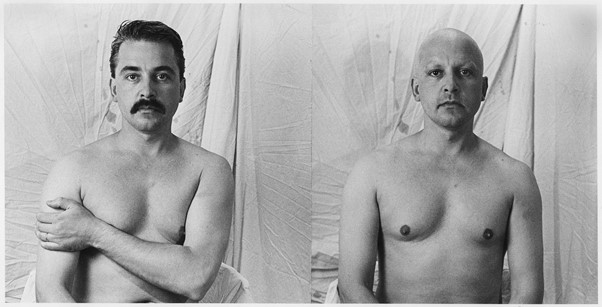

Self-Portrait (Double Portrait) (1990; fig. 15) combines two studio portraits of the artist—one in which he has hair on his head and face, and the other in which he does not. He otherwise sits topless in the same chair in the same room, with the same pale, crumpled fabric in the background. In both images, the bottom part of his body cropped out. The setting, lighting, and composition, as well as the crinkles of the backdrop, all seem to affirm the rigid logic of time: two photographs taken shortly, one after the other. At first, the artwork suggests a “before-and-after” narrative: a person who can make himself contingently different, in essence, remains the same. However, as with Põder’s Very Old Memories, a hand gesture suggests another, incidental detail: In the portrait on the left, the artist’s left hand rests below the opposite shoulder, exposing his wedding ring. Meanwhile, in the one on the right, he sits with his arms down, and his hands cropped out.

Self-Portrait is one of the most recognized works by Šonta. Featured in the only posthumously published catalogue of his work, it can also be found in more than one Lithuanian museum collection. Yet it has an unpublished double in the “private” archive that dramatically reframes the well-known photograph (fig. 16). This time, the shaven Šonta is on the left. On the right, his hand’s gesture is markedly performative, hiding the left nipple without attempting to hold the upper arm. This shift puts the much-publicized self-portrait in a new light, betraying the exposition of the wedding ring as a performative gesture. Likewise, the differences between the bottom of Double-Portrait and its doppelganger (figs. 15, 16) reveal the crop as a deliberate artistic device. Here, Šonta appears naked in two ways. He removes his clothes and the entirety of his facial hair, but more significantly, the “irrelevant” photographic detail discloses the wedding ring, which is subsequently out of sight and cropped out.

The two photographs use montage as a technique for ordering time and multiplying the possible states of subjecthood. As George Baker has argued, “In photography . . . we confront an endless doubling that is also a process of endless difference—not sheer or indexical replication—a copying that doubles, but is never the same.”14George Baker, “The Black Mirror,” October, no. 158 (Fall 2016): 49. Šonta’s use of doubling is a photo-performance of his own self-differing. The photographs trace his subjecthood as one that is decidedly not singular.

On the one hand, his doubled subjecthood as a gay man married to a woman, a circumstance that marks his era and place, is rendered through the form and narrative of the two Self-Portraits. On the other, this twofold identity, specific to the legal, political, and social circumstances of late Soviet Lithuania, shapes the two artworks, and not least, the relations of proximity they sense. Do Šonta’s homoerotic photographs, then, function exclusively as social documents—evidence of defiant acts in the face of the legal and social frameworks of their time? Or, do they, like Põder’s works, puncture the barriers of chronology and carve out a trajectory of a time yet to come?

It all hinges on the structures of feeling that the formal decisions within Šonta’s homoerotic photography carry. In Morning (fig. 11), the cropping off of the young man’s lower body defers desire to future viewers’ encounters with the photograph as it pushes us to live out this lack, to fantasize a relation that is not represented, to desire to complete these images that cannot be completed. In Untitled (fig. 13), the suggestive contours of the male genitalia, which are covered by the briefs, target libidinal drives. The absence of explicit nudity in effect produces a libidinal economy. The images come alive when their affective structure resonates with the responses within their viewers’ own bodies. Alongside lust, another interdependence unfolds through Šonta’s images. His use of composition, cropping, blurring, and shading does not allow one to identify his protagonists, thereby protecting them from unwanted attention. Not just desire but care for the subjects permeates Untitled (fig. 13), Morning (fig. 11), and other photographs in the series (figs. 12, 14).

More than signifying subject matter on the surface of bodies that we now recognize as feminist or queer, Põder’s and Šonta’s artworks are committed to partially inaccessible bodily interiorities and particular structures of feeling via a shared formal maquette of repetition, doubling, deferral, obfuscation, and fragmentation. These latently feminist and queer structures of feeling, respectively, resurface through sensitive encounters between the works of art and the viewers responding to them. The specific late Soviet historical context not only modifies the forms that feminist and queer works of art took but also continues to inform the modes of proximity and affect these artworks carry through time.

Within models of regional uniformity and conformism vs. dissidentism, these works can be reduced to an assumed “belatedness” and “irrelevance” of the Baltics to both regional and global postwar art histories.15On self-acceptance of the logic of belatedness, see Francisco Martínez, Remains of the Soviet Past in Estonia: An Anthropology of Forgetting, Repair and Urban Traces (London: UCL Press, 2018), 212; and Neda Genova, “‘A Better Past Is Still Possible.’ Interview with Boris Buden,” LeftEast, April 7, 2018, http://www.criticatac.ro/lefteast/a-better-past-is-still-possible-interview-with-boris-buden/. Põder’s and Šonta’s art practices do not fit into the reductive conformist–dissident binary. Neither artist was regarded as a leading figure in their local artistic milieu nor celebrated as a counter-figure after independence; nor was either one part of neo-avant-garde movements that paralleled those in the West. As such, their works can be read as anachronistic—or examples of “belated” humanist photography and post-minimalist sculpture respectively. And yet, what if we do not foreclose their relation to time past and present?

The relative lack of interest that persisted under the radically different sociopolitical and economic realities of late Soviet-era and neoliberal capitalism points to a potentiality within the artworks themselves. Their continued untimeliness showcases precisely their transformative possibility—an epistemic disobedience with regard to assimilation and ossification into a moment past or present.16Walter D. Mignolo, “Geopolitics of Sensing and Knowing: On (De)Coloniality, Border Thinking, and Epistemic Disobedience,” Transversal Texts (blog), September 2011, https://transversal.at/transversal/0112/mignolo/en. These artworks alter time passing through them as much as passing time alters them. As such, they ask to be recognized as embodied forms of knowledge possessing the agency to modify the “universal” theoretical or preestablished historical framings one employs to read them.17“It is not sufficient to write a history of a problem for that problem to be resolved. A theoretical object is something that obliges you to do theory . . . but it also furnishes you with the means to do it.” Hubert Damisch, “A Conversation with Hubert Damisch,” by Yve-Alain Bois, Denis Hollier, and Rosalind Krauss, October, no. 85 (Summer 1998), 8. These artworks demand that one “pays the closest possible attention to their materiality, phenomenality, their singularities, their effects, and their uses.”18Xavier Vert, “Expectation of Art: The History of Its Theoretical Bases,” trans. Simon Pleasance, Critique d’art: Actualité internationale de la littérature critique sur l’art contemporain / International Review of Contemporary Art Criticism 39 (Spring 2012): 3. This attentiveness leads to matters of body and history, or rather, of differing bodies in nonlinear histories.

Alongside Põder’s and Šonta’s untimely artworks, many other artworks in the Baltics remain deferred, an unthought known, or a form of knowledge that is yet to be thought. The translation of untimely artworks into the field of art history entails a desire to grasp their mode of address. This address makes it difficult to assimilate them into the homogenous narratives of the regional past and discourses based on Western-centric theory, which would place them as late sidekicks to the arrow of time.19See Martina Pachmanová, “In? Out? In Between? Some Notes on the Invisibility of a Nascent Eastern European Feminist and Gender Discourse in Contemporary Art Theory,” in Gender Check: A Reader; Art and Theory in Eastern Europe, ed. Bojana Pejic (Köln: Verlag der Buchhaltung Walther König, 2010); and Jovana Stokic, “Un-Doing Monoculture: Women Artists from the ‘Blind Spot of Europe’—the Former Yugoslavia,” ARTMargins Online, March 10, 2006, https://artmargins.com/un-doing-monoculture-women-artists-from-the-blind-spot-of-europe-the-former-yugoslavia/. Such difficulty speaks to the political and epistemological disobedience they embody to this day. The artworks of Anu Põder and Virgilijus Šonta nuance our understanding of the late Soviet period. In their temporal excess, quietly and resolutely, they insist that the “universal” techniques of looking and writing must change for the latent global dialogues in art history to truly begin.20On critically assessed notion of the “global,” see Mignolo, “Geopolitics of Sensing and Knowing”; on potential pitfalls of “the global” and a roadmap toward reciprocal, sustainable local-to-local art historization, see Zdenka Badovinac, “The Sustainable Museum,” May 10, 2017, Glossary of Common Knowledge website, https://glossary.mg-lj.si/referential-fields/other-institutionality/sustainable-museum. As much in the 2020s as in the 1980s, they take off the seal of time, for the benefit of what is, let us hope, yet to come.

- 1For Anu Põder, this includes Be Fragile! Be Brave!, a major retrospective in Tallinn’s Kumu Art Museum in 2017, which led to the acquisition of the majority of the artist’s previously uncollected works by the National Art Museum of Estonia. International exposure has followed—firstly, in the 13th Baltic Triennial (2018), and most recently, in the Liverpool Biennial of Contemporary Art (2021) and Tate Modern, which has acquired work by the artist. Incidentally, since I began my research into the intimate part of Virgilijus Šonta photographic archive in spring 2020, Lithuanian National Broadcaster (LRT) has published the following: Mindaugas Klusas, “Homoseksualumą ilgai neigęs fotografas Šonta su savimi susitaikė tik prieš kraupią baigtį,” December 6, 2020, https://www.lrt.lt/naujienos/kultura/12/1290350/homoseksualuma-ilgai-neiges-fotografas-sonta-su-savimi-susitaike-tik-pries-kraupia-baigti; and “Homoseksualaus fotografo Virgilijaus Šontos meilė ir žūtis: prabyla mylimasis, įtariamasis, anonimas,” February 14, 2021, https://www.lrt.lt/naujienos/kultura/12/1341609/homoseksualaus-fotografo-virgilijaus-sontos-meile-ir-zutis-prabyla-mylimasis-itariamasis-anonimas. Likewise, the first exhibition of these previously unpublished homoerotic auto-fictional photographs was held in September 2020 at The Naked Room, a gallery in Kiev, Ukraine.

- 2Klara Kemp-Welch, Networking the Bloc: Experimental Art in Eastern Europe, 1965–1981 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2019), 365–66.

- 3See ibid. See also Arūnas Streikus, “What Made Modernism So Quiet? The Particularities of the Art Field in the Soviet West,” Acta Academiae Artium Vilnensis 95 (2019): 14–28; and Erika Grigoravičienė, “Modernisation, (Post)Modernities, and New Modernism: The Concepts of Lithuanian Art History Starting from the Late 1950s,” ibid., 53–85.

- 4For “the regime against the dissident” art historical model, see Alla Rosenfeld and Norton D. Dodge, eds., Art of the Baltics: The Struggle for Freedom of Artistic Expression Under the Soviets, 1945–1991 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; Rutgers, NJ: Jan Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, State University of New Jersey, 2002), 3.

- 5Rebeka Põldsam, “Anu Põder. Be Fragile! Be Brave!,” in Anu Põder. Be Fragile! Be Brave!, ed. Rebeka Põldsam, exh. cat. (Tallinn: Kumu Art Museum, 2017), 11.

- 6Anu Põder, video interview by Isabel Aaso-Zahradnikova and Juta Kivimäe for the archives of the Art Museum of Estonia, 2007, Estonian National Museum, Tallinn.

- 7Eha Komissarov, “Three Stories about the Work of Anu Põder,” in Anu Põder. Be Fragile! Be Brave!, 50.

- 8Põldsam, “Anu Põder. Be Fragile! Be Brave!,” 19.

- 9See Komissarov, “Three Stories about the Work of Anu Põder,” 44; and “Jaan Elken Interviews Anu Põder, 2008,” in Anu Põder, ed. Reet Varblane (Tallinn: Tallinna Kunstihoone Fond, 2009), 45.

- 10Yve Alain Bois and Rosalind Krauss, Formless: A User’s Guide (New York: Zone Books; Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1997), 18.

- 11Põldsam, “Anu Põder. Be Fragile! Be Brave!,” 13.

- 12See Põldsam, “Anu Põder. Be Fragile! Be Brave!”; and Komissarov, “Three Stories about the Work of Anu Põder.”

- 13Georges Didi-Huberman, Confronting Images: Questioning the Ends of a Certain History of Art (University Park: Penn State University Press, 2009), 179.

- 14George Baker, “The Black Mirror,” October, no. 158 (Fall 2016): 49.

- 15On self-acceptance of the logic of belatedness, see Francisco Martínez, Remains of the Soviet Past in Estonia: An Anthropology of Forgetting, Repair and Urban Traces (London: UCL Press, 2018), 212; and Neda Genova, “‘A Better Past Is Still Possible.’ Interview with Boris Buden,” LeftEast, April 7, 2018, http://www.criticatac.ro/lefteast/a-better-past-is-still-possible-interview-with-boris-buden/.

- 16Walter D. Mignolo, “Geopolitics of Sensing and Knowing: On (De)Coloniality, Border Thinking, and Epistemic Disobedience,” Transversal Texts (blog), September 2011, https://transversal.at/transversal/0112/mignolo/en.

- 17“It is not sufficient to write a history of a problem for that problem to be resolved. A theoretical object is something that obliges you to do theory . . . but it also furnishes you with the means to do it.” Hubert Damisch, “A Conversation with Hubert Damisch,” by Yve-Alain Bois, Denis Hollier, and Rosalind Krauss, October, no. 85 (Summer 1998), 8.

- 18Xavier Vert, “Expectation of Art: The History of Its Theoretical Bases,” trans. Simon Pleasance, Critique d’art: Actualité internationale de la littérature critique sur l’art contemporain / International Review of Contemporary Art Criticism 39 (Spring 2012): 3.

- 19See Martina Pachmanová, “In? Out? In Between? Some Notes on the Invisibility of a Nascent Eastern European Feminist and Gender Discourse in Contemporary Art Theory,” in Gender Check: A Reader; Art and Theory in Eastern Europe, ed. Bojana Pejic (Köln: Verlag der Buchhaltung Walther König, 2010); and Jovana Stokic, “Un-Doing Monoculture: Women Artists from the ‘Blind Spot of Europe’—the Former Yugoslavia,” ARTMargins Online, March 10, 2006, https://artmargins.com/un-doing-monoculture-women-artists-from-the-blind-spot-of-europe-the-former-yugoslavia/.

- 20On critically assessed notion of the “global,” see Mignolo, “Geopolitics of Sensing and Knowing”; on potential pitfalls of “the global” and a roadmap toward reciprocal, sustainable local-to-local art historization, see Zdenka Badovinac, “The Sustainable Museum,” May 10, 2017, Glossary of Common Knowledge website, https://glossary.mg-lj.si/referential-fields/other-institutionality/sustainable-museum.