Grace Salome Kwami (1923–2006) was undoubtedly a forerunner of modern art in the colonial Gold Coast, now Ghana.1This is my second short article on Da Grace, “Da” being an Ewé term of respect. The first—Elsbeth Court, “Da Grace Salome Abru Kwami, 1923–2006,” African Arts 41, no. 2 (Summer 2008), 10–11—followed my 2007 visit with Pamela Clarkson and Atta Kwami in Ayeduase (near Kumasi, their college home) and Ho (their family home). In both places, I was in the presence of Da Grace’s terra-cotta portrait sculptures and sensed an awareness of her career as an art educator. This essay takes a closer look at Da Grace’s artistic formation, key works, and restitution. My first, highly aspirational experience in Ghana was with Operation Crossroads Africa in 1964. She was among the first women to undertake an academic training in fine art, which presaged her lifelong professional career in the teaching and making of art. In the absence of female role models, she shaped a practice characterized by a strong domestic sense, maternal sensitivity, and local affinities; she was an intuitive rather than reflective feminist. The year 2022 is an opportune time to recover her story because it resonates so clearly with three topical “moments”: the resurgence of figurative imagery, especially Black figuration; the recovery of Independence-era African artists, particularly women; and the heightened inclusion of clay and ceramic art forms in contemporary art as seen, for example, in the Biennale Arte 2022: The Milk of Dreams, the 59th International Exhibition in Venice.

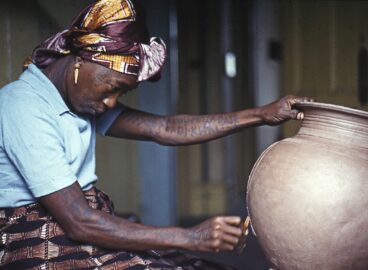

Grace Salome Abra Anku (hereafter “Da Grace”) was the third youngest child in an Ewé Christian family who lived in the highlands of the Volta Region, then British Togoland. She was precocious. Indeed, she attended school underage at the mission station where her father was the catechist and head teacher. At age four, she excelled at modeling objects in clay. Her post-primary education brought a mix of vocational certificates in teacher training and domestic/home science that included weaving.2This and another course taken by Da Grace included practical textile weaving. Such knowledge was prohibited in the cultural contexts of Asante and Ewé, where weaving kente cloth is the gender-specific work of men. This example shows how the intervention of formal/Western art education expanded opportunities for women. She then taught for several years before joining the Specialist Art and Crafts course at Achimota College in Accra (which in 1952, moved to the Kumasi College of Technology). Here, she excelled in painting and sculpture, specifically portraiture. The genre, taught through drawing from observation, was a significant innovation in the art education of both genders. At age thirty, she married Robert Kwami, also from a prominent Ewé Christian family, who was head of music at the renowned Achimota School. In Achimota, she set up her home studio, worked part-time in the Achimota College museum,3Da Grace was tasked with the display and repair of archaeological objects, said to include terra-cotta funerary portrait heads; this direct contact deepened her understanding of precolonial visual culture (Atta Kwami, discussion with author, July 4, 2021). At that time (1954–57), Achimota College housed the Archaeology Department, University College of the Gold Coast. Previous publications incorrectly state that Da Grace worked in the National Museum, which opened in 1957. and mothered three children. Tragically in 1957, in the fourth year of their marriage, Robert died, leaving Da Grace to raise their children and pursue her practice alone. She returned to the Volta Region to teach at a secondary school that provided housing. This astute decision gave her familial support, financial security, and a home studio. The focus of her oeuvre continued to be figurative portraiture, which was distinctive during the Independence era.

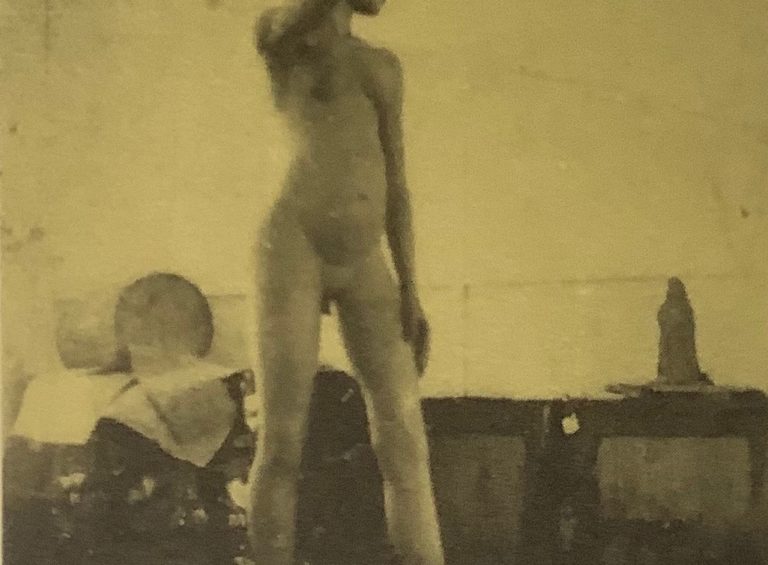

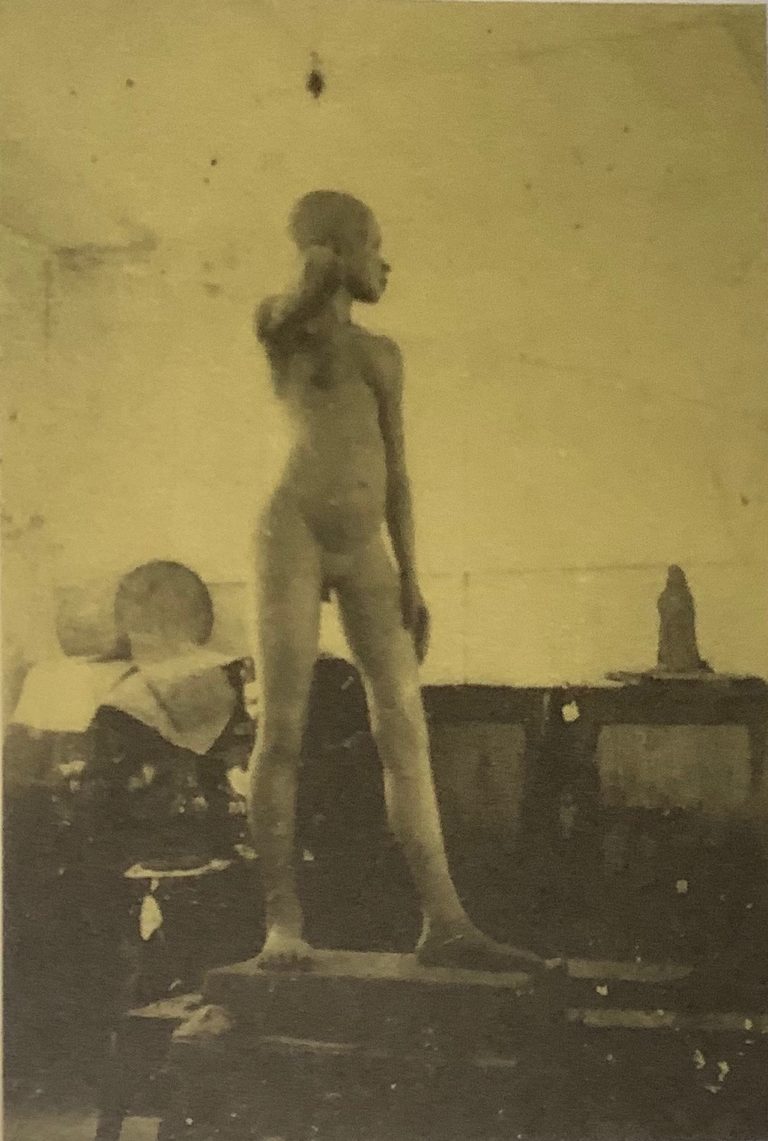

In the 1950s–mid-1960s, Da Grace’s talent was actively supported by leading modern artists Dr. Oku Ampofo (1908–1998) and Kofi Antubam (1922–1964),4Kofi Antubam, Ghana’s Heritage of Culture (Leipzig: Koehler and Amelang, 1963), 208. Ampofo cited in Court, “Da Grace Salome Abru Kwami, 1923–2006,” 11. and her work was exhibited in several public shows in Accra. In 1961, the Ghana Society of Artists recommended her to the Harmon Foundation in New York for inclusion in a documentary exhibition of contemporary African artists; this led to a significant correspondence between Da Grace and the foundation’s assistant director, Evelyn Brown.5Grace Kwami File Box 89, Records of the Harmon Foundation, Inc. (1913–1967), Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC. An exchange of letters (1961–62) was initiated by the assistant director of the Harmon Foundation, Evelyn Brown, who requested that Da Grace provide her resumé and photographs of her artwork. Da Grace replied; Brown then invited the artist to send a painting for consideration for purchase (without mention of shipment costs). Da Grace sent one more letter to share news of the 1962 exhibition 3 Housewives in Accra (note the patronizing title, given that Da Grace was not only a widow but also a teacher). Tellingly, Da Grace sent two staged photographs in which she is painting and sculpting portraits in her studio. The image with clay objects (fig. 2) is apposite in that it offers a purview of Da Grace’s art world during the early years of nationhood. It was a world in which she combined her affective knowledge of Ewé and West African cultures with the anglicization she acquired through formal education and exposure to English culture.

In her Harmon photograph, Da Grace, wearing a European-style floral-print dress, is finishing a terra-cotta portrait of a boy/youth in her home studio on the campus of Mawuli School. A selection of diverse, ceramic objects surrounds the large head, including (left to right): the artist’s northern-style bowl, assorted English crockery (the Kwamis had lived in London), her small portrait head, and a section of her largest and most complex piece, Drum (ca. 1960), which depicts a community of people of all ages carrying their oversize drum to a village meeting. According to the artist’s son Atta Kwami (1956–2021), the sculpture, which “stands for the social cohesion of community and its value to society, is her most patriotic work.”6Atta Kwami, discussion with author, July 4, 2021. In 1986, she made a small replica of Drum; neither piece survives. In her inclusive notion of art, she made “no split between art-craft-design.”7Ibid.

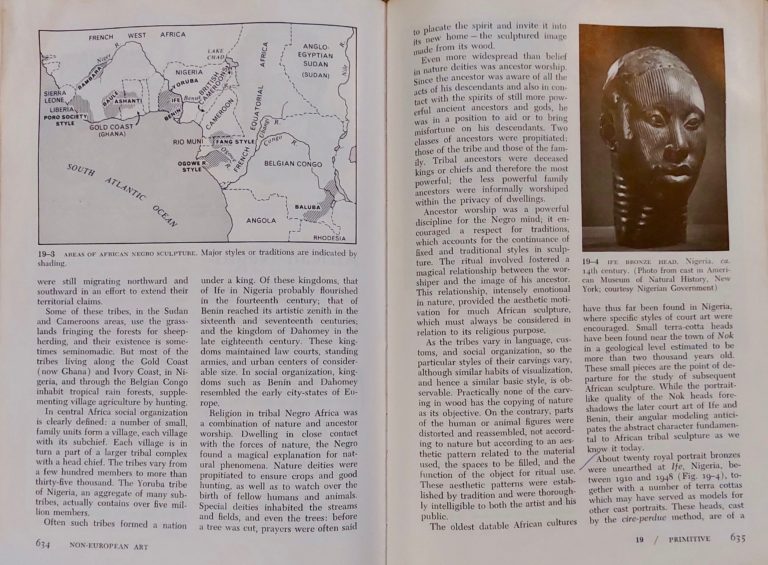

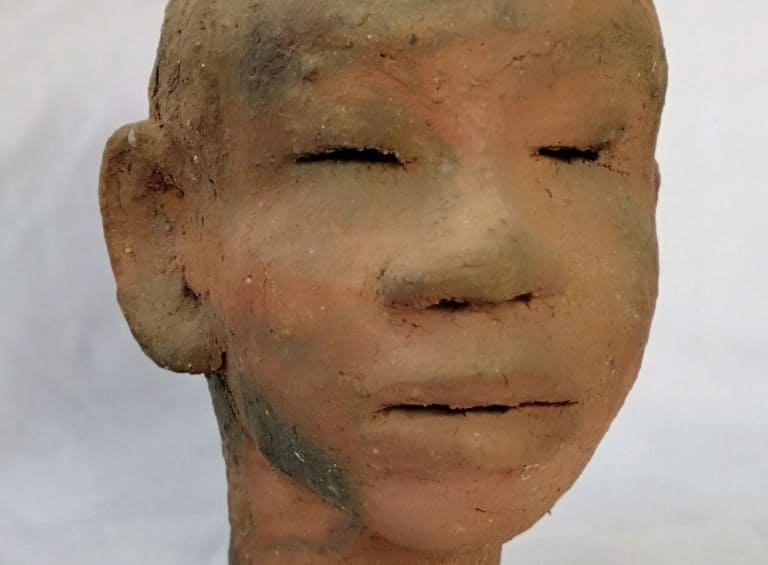

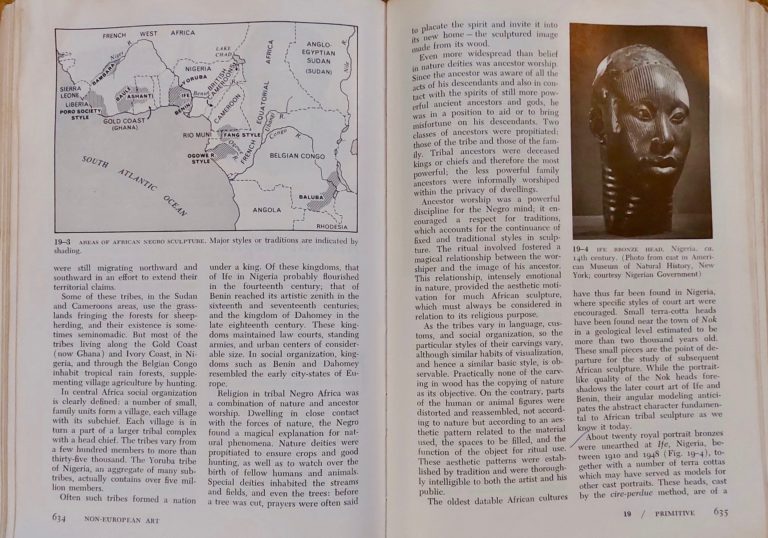

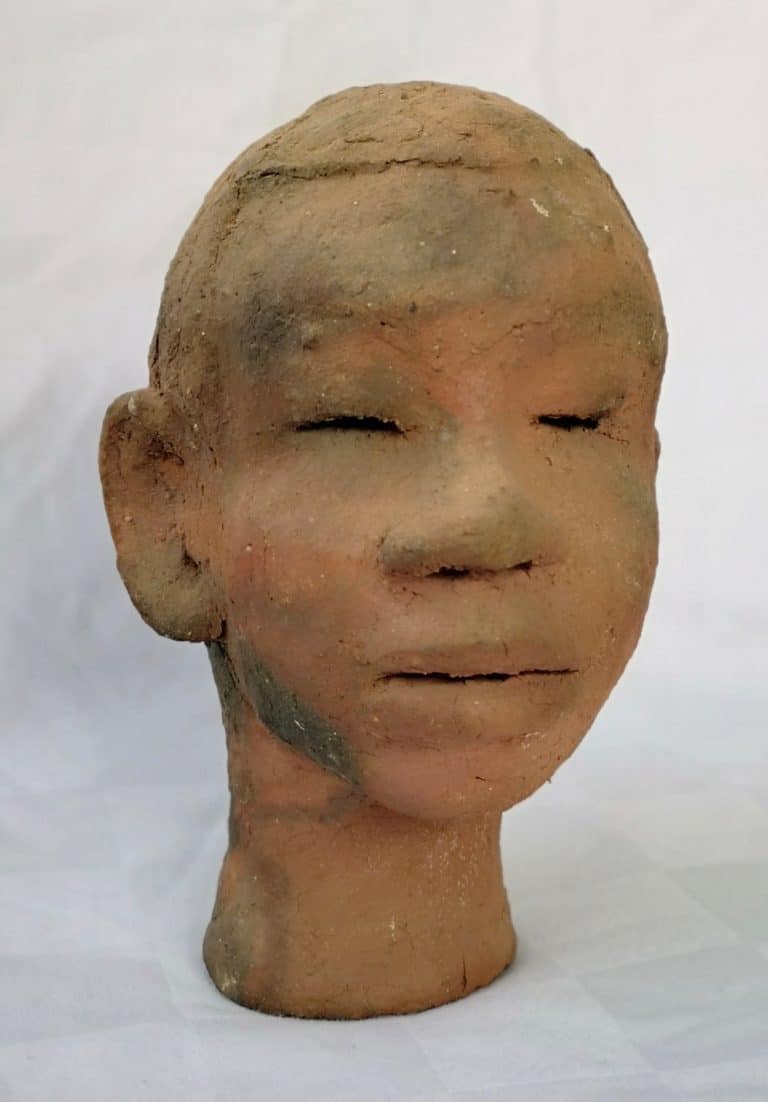

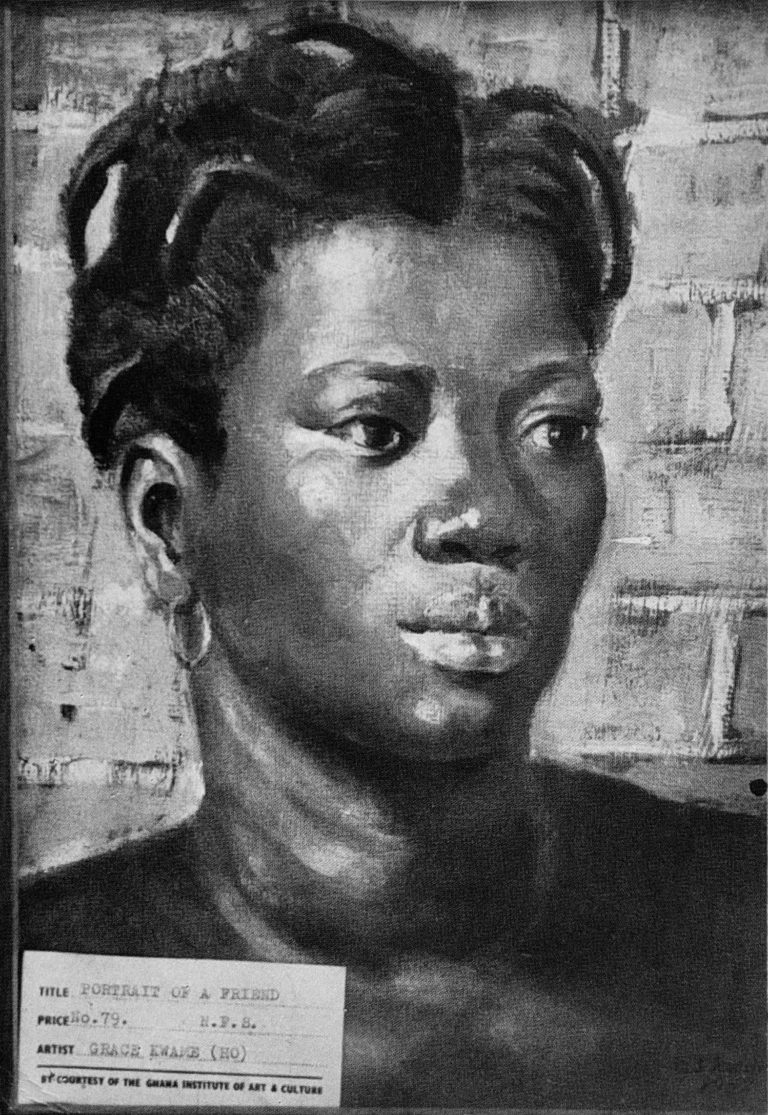

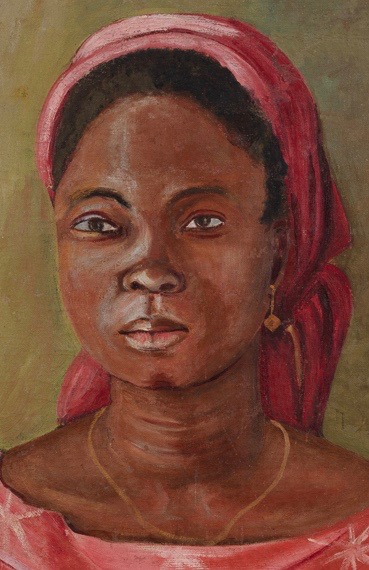

Da Grace’s Harmon photograph also prompts consideration of how she applied her Western academic training to her own visual language. This can be seen by comparing her college and post-college work. For example, Portrait of a Boy’s Head (fig. 3) and Asante Girl (fig. 4) are studies that were carried out under the instruction of a tutor from visual observation with the objective of mimesis. Her subsequent portraits also portray ordinary people, often women and children, rendered with greater subjectivity and expression. At that time, portrayal of commoners was an extension, if not a transgression, of the classical sculpture traditions for commemorative heads in the West African kingdoms. These were well-known to Da Grace from her college art history course, as can be seen in the textbook for the course (fig. 5),8Da Grace’s college art history course used the popular survey text Art through the Ages, which covers formal portraiture. The section on Non-European Art is comprised of seven chapters. Chapter 19 “Primitive (13th–20th Centuries)” begins pejoratively on page 632, “Primitive art is that produced by people who have no written literature, live in tribes, often still in a Neolithic cultural state” and then, in contradiction, describes the art of the kingdoms of Ife and Benin; it erroneously posits on page 633 that the Benin bronzes “were discovered by a British army expedition.” See Helen Gardner, Art through the Ages, ed. Sumner McKnight Crosby, 4th ed. (London: G. Bell and Sons, Ltd., 1959). Many years later, Da Grace recalled that “her art history course did not include modern art by Africans.” Atta Kwami, discussion with author, July 4, 2021. and her stint at the Achimota College museum. From this classical genre, it is likely that she retrieved—for use in her own practice—the special significance of the head and its dignified composure. Her application of these characteristics to figurative realism is among her contributions to the Ghanaian version of African modernism.9Atta Kwami, Kumasi Realism, 1951–2007: An African Modernism (London: Paul Hurst and Company, 2013), 28–32, 43. These observations can be seen in figs. 6–8. Also relevant is her college study Portrait of a Friend (fig. 9), which bears some likeness to an Ife bronze head (fig. 5) and to the melancholic countenance of A Girl in Red (fig. 11).

Between the late 1960s and mid-1980s, a combination of adverse conditions, familial and national, delimited Da Grace’s artistic potential and dashed her hope “to become a full-time sculptor.”10Da Grace to Elizabeth Brown, April 19, 1961, Grace Kwami File Box 89, Records of the Harmon Foundation, Inc. (1913–1967), Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC. Her artistic presence faded, largely due to the unsupportive climate for modern art in Ghana during eighteen years of military rule and economic depression.11For example, the price of her small “head” sculptures was higher in 1962 than in 1991; yet each receipt was less than fifteen dollars. Significant familial challenges included the death of her daughter, Attawa, in 1969, after which Da Grace transferred to Tamale Women’s Training College in northern Ghana (she returned to Ho in 1978), and during the 1980s, the absence of her well-educated sons, who were teaching in Nigerian colleges. Conditions eventually improved, and gradually, her story is being reclaimed, initially by her son Atta Kwami through his own art-making (fig. 16) and art historical research.12Atta Kwami, Grace Kwami Sculpture (London: Royal College of Art, 1993); and Kwami, Kumasi Realism, 1951–2007. More recently, her role in cofounding the Sankofa movement with artists Kofi Antubam (1922–1964) and Vincent Kofi (1923–1974) was cited in the Ghana Freedom pavilion at the Biennale Arte 2019: 58th International Art Exhibition in Venice.13Nana Oforiatta Ayim, “Ghana Freedom,” in Ghana Freedom: Ghana Pavilion at the 58th International Art Exhibition; La Biennale di Venezia (London: König Books, 2019), 28. The Sankofa movement envisioned a distinctive Ghanaian modernism blending colonial/academic training with select African traditions. El Anatsui, a lecturer who taught art education using “Sankofa syndrome” at college level (1969–75), gives an excellent firsthand account. See El Anatsui, ‘‘Sankofa: Go Back an’ Pick’: Three Studio Notes and a Conversation,” Africa Special Issue, Third Text 7, no. 23 (1993): esp. 45 and 50–51. For Da Grace and Anatsui, both Ewé speakers, the Sankofa movement reprised an Ewé proverb—xoxo na wogbea yeye do—about growth that is critical in the oral literature about their forebears’ legendary story of migration, involving diplomacy and the efficacy of clay as an art material [the proverb’s translation is complex which why I have omitted it; ‘local’ understanding is contingent on awareness of the legend in Third Text above or Okwui Enwezor & Chika Okeke-Agulu. El Anatsui The Reinvention of Sculpture (2022, Damini),101. The simple version is “The new is woven on to the old”. N.K. Dzobo. African Proverbs Guide to Conduct The Moral Value of Ewe Proverbs (1973, University of Cape Coast), 73. Anatsui prefers a translation that is closer to the legend, ”It is on the sample of the old rope that one weaves the new one,” Anatsui 1993, 51; e-mail correspondence to the author, May 8, 2022.] Da Grace’s profile as a woman artist, practitioner in clay, modernizer of portraiture, art educator, and promoter of Ewé oral literature (through radio broadcasts) extended the reach of the movement. Currently, in an exemplary act of collaborative restitution, Da Grace’s most accomplished painting, A Girl in Red (1954), will be in the exhibition African Modernism in America, 1947–67, which reinterprets the Harmon Foundation’s 1961 breakthrough exhibition Art from Africa of Our Time.14Perrin Lathrop, “African Modernism in America. 1947–1967,” African Arts 54, no. 3 (Autumn 2021): 68–81.

A coming-of-age portrait, A Girl in Red (fig. 11) depicts Gladys Ankora, a guest from the Kwami’s homeland, possibly during her first visit to Accra. Filling most of a monochrome picture space, the subject’s solitary half-length figure is composed of soft, curvy shapes. A warm palette of earthy colors with mild luminosity creates harmony between the figure and the ground, complementing the color of the girl’s skin. Her arms appear relaxed, while her chest, neck, and face are rendered with more volume. She is well-dressed in a light red, scoop-neck dress and matching head scarf; arcs of red textile frame her face. According to Antubam in Ghana’s Heritage of Culture,15Antubam, Ghana’s Heritage of Culture, 82. the wearing of red by Ewé girls signifies the melancholy associated with puberty. This awareness of life-cycle transitions is evoked in the portrait’s tantalizing title and content—though she looks physically mature, Gladys had not yet attained the social status of womanhood and was no doubt anxious about her future.

The narrative continues with the delicate gold jewelry that Gladys is wearing: Ghanaian filagree drop earrings and a chain that is partially covered by her dress. The occluded pendant raises a query: is it a cross or a heart? Gladys’s pretty, round face appears younger, less angular, than that of the friend in fig. 9. However, both women are portrayed with anxious expressions, far more emotive than the calmness associated with Da Grace’s other portraiture. Indeed, A Girl in Red is distinguished by the penetrating stare of Gladys’s slightly uneven eyes! That stare is the consequence of Da Grace’s female gaze. Her empathy for her sitters evolved from her long experience of mentoring girls and from her own belated transition to marriage and motherhood. No other Independence-era Ghanaian artist created figurative imagery that is as specific and as compassionate as A Girl in Red.

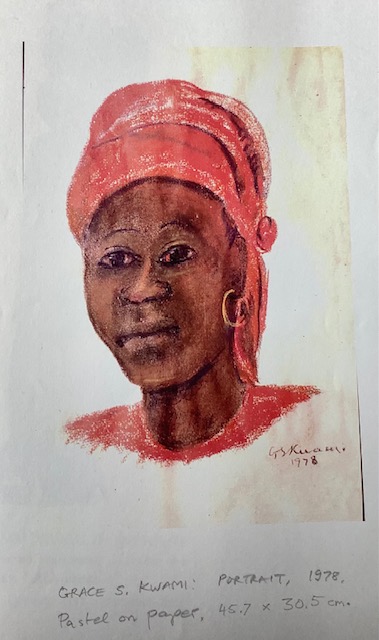

For forty years Da Grace returned again and again to this theme. For example, the imagery in a pastel sketch from 1978 (fig. 12), said to be a self-portrait, is more schematic and less observed than her earlier portraiture. As she lost exactitude in her ability to capture close likenesses, she shifted to a more impressionistic style—as can be seen in her final oil painting, Woman in Red (1994).

Upon her retirement from teaching in the early 1980s, Da Grace built her own house and became a full-time artist. Working in clay, she modeled a wide range of robust portraits (fig. 13), including in nonrepresentational formats, such as a hearth (fig. 14). Her final portrait depicts the head of a child whose visage blends bright youthfulness with the stillness of West African terra-cotta funerary sculpture (fig. 15). Possibly, it is a tribute to her eldest son, who passed away in 2004. Da Grace also carried out experiments with gourds, cultivated in her own garden, incorporating pyro-techniques and assemblage sculpture.16Kwami, Grace Kwami Sculpture; and Atta Kwami, discussion with author, July 5, 2021. To generate additional income, she made beaded jewelry and artifacts that also gave her credibility with Ho market women, whose company she enjoyed. In the artistry she brought to everything she touched, Da Grace was a consummate artist.

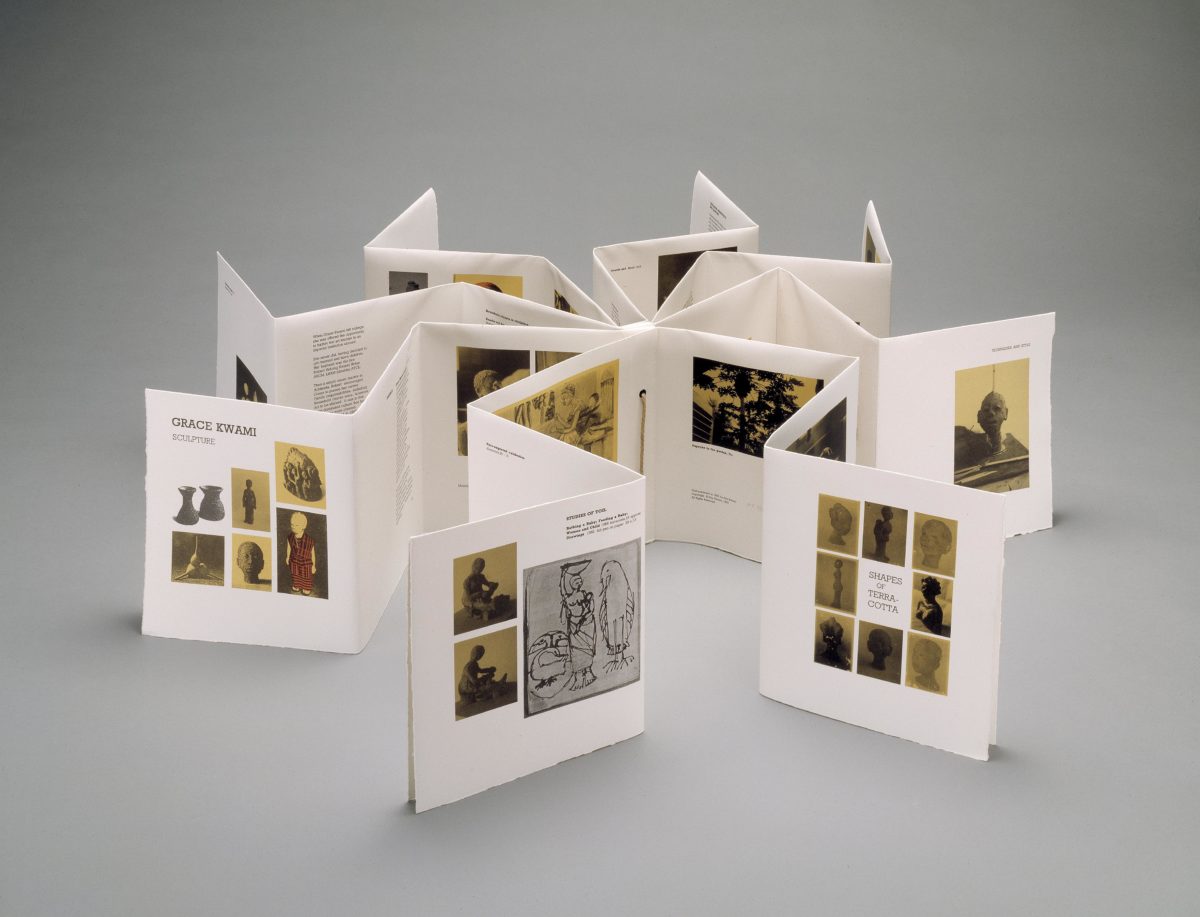

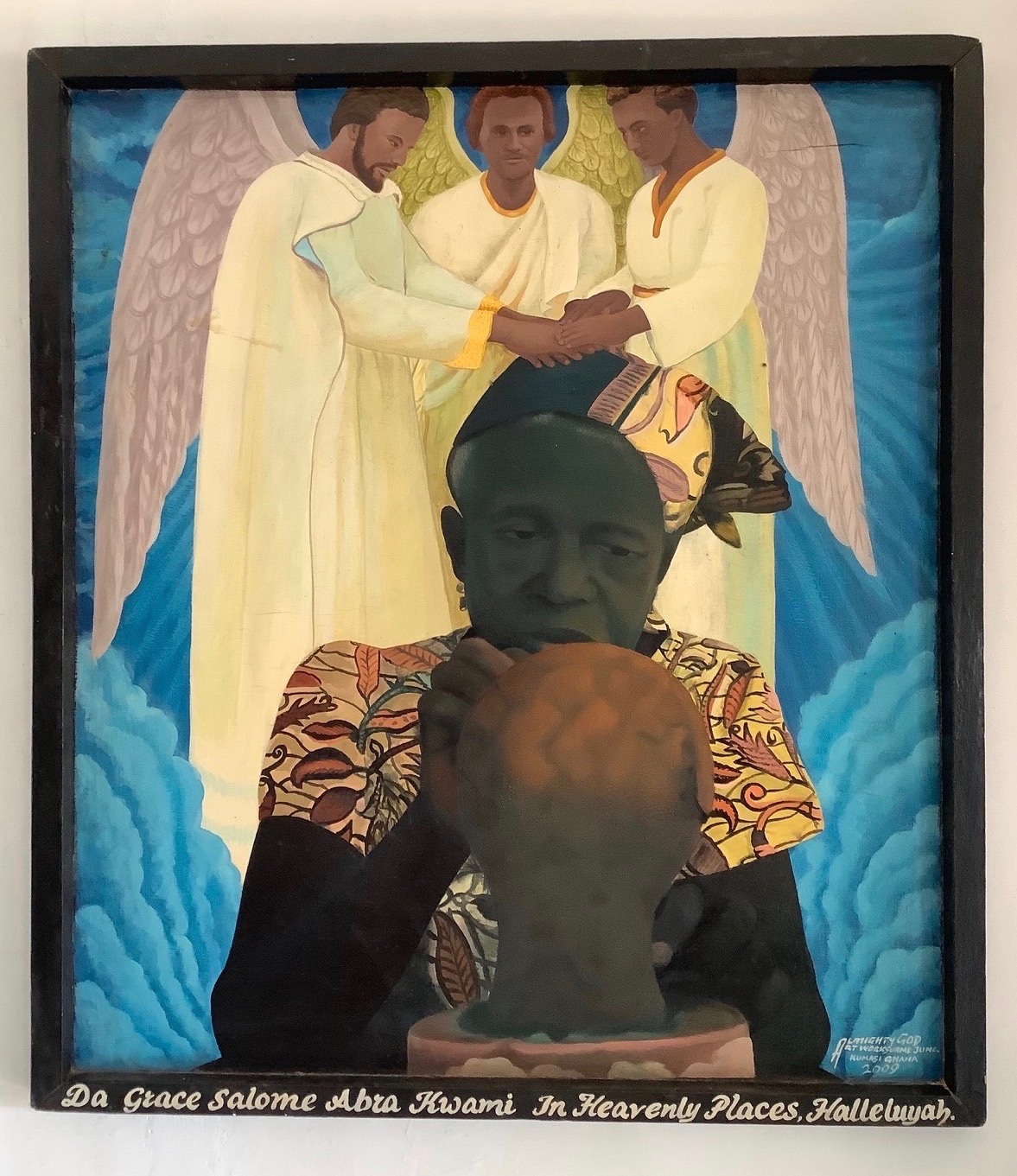

Prior to the international restitution of her career, Da Grace’s life was memorialized locally in an art space in Ghana and by two special works that focus on her clay portraiture. These are the artist’s book Grace Kwami Sculpture (fig. 16) by Atta Kwami and Da Grace Salome Abru Kwami In Heavenly Places, Halleluyah (fig. 17) by urban painter Kwame Akoto (born 1959), aka “Almighty God.” Akoto’s portrait speaks for itself—apart from the shift in Da Grace’s religious beliefs toward an Asian universalist spirituality. A mini-exhibition in the form of the iconic storytelling spider Ananse, Grace Kwami Sculpture provides a carefully curated portrait of the artist’s life through photographs of her sculpture (throughout her career) and Atta’s insightful text.17For further images and text, see “Grace Kwami Sculpture,” in “Artists’ Books and Africa,” Smithsonian Libraries website, https://library.si.edu/exhibition/artists-books-and-africa/grace-kwami-sculpture-full. Lastly, the 2012 establishment of Grace Salome Kwami House in Ho is a living memorial for “the promotion of [her] art and intellectual legacy in the community where she operated.”18See Grace Salome Kwami House facebook page, https://www.facebook.com/gracesalomekwamihouse/. Its holdings include her artworks and other examples of modern Ghanaian art.

With the author’s grateful thanks to Atta Kwami, RIP; Pamela Clarkson; Amanda Beardsmore; Perrin Lathrop; John and Sue Picton; Janet Stanley; Benjamin Kankpeyeng; Christopher DeCorse; Deborah Radcliffe and Emmanuel Anatsui.

- 1This is my second short article on Da Grace, “Da” being an Ewé term of respect. The first—Elsbeth Court, “Da Grace Salome Abru Kwami, 1923–2006,” African Arts 41, no. 2 (Summer 2008), 10–11—followed my 2007 visit with Pamela Clarkson and Atta Kwami in Ayeduase (near Kumasi, their college home) and Ho (their family home). In both places, I was in the presence of Da Grace’s terra-cotta portrait sculptures and sensed an awareness of her career as an art educator. This essay takes a closer look at Da Grace’s artistic formation, key works, and restitution. My first, highly aspirational experience in Ghana was with Operation Crossroads Africa in 1964.

- 2This and another course taken by Da Grace included practical textile weaving. Such knowledge was prohibited in the cultural contexts of Asante and Ewé, where weaving kente cloth is the gender-specific work of men. This example shows how the intervention of formal/Western art education expanded opportunities for women.

- 3Da Grace was tasked with the display and repair of archaeological objects, said to include terra-cotta funerary portrait heads; this direct contact deepened her understanding of precolonial visual culture (Atta Kwami, discussion with author, July 4, 2021). At that time (1954–57), Achimota College housed the Archaeology Department, University College of the Gold Coast. Previous publications incorrectly state that Da Grace worked in the National Museum, which opened in 1957.

- 4Kofi Antubam, Ghana’s Heritage of Culture (Leipzig: Koehler and Amelang, 1963), 208. Ampofo cited in Court, “Da Grace Salome Abru Kwami, 1923–2006,” 11.

- 5Grace Kwami File Box 89, Records of the Harmon Foundation, Inc. (1913–1967), Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC. An exchange of letters (1961–62) was initiated by the assistant director of the Harmon Foundation, Evelyn Brown, who requested that Da Grace provide her resumé and photographs of her artwork. Da Grace replied; Brown then invited the artist to send a painting for consideration for purchase (without mention of shipment costs). Da Grace sent one more letter to share news of the 1962 exhibition 3 Housewives in Accra (note the patronizing title, given that Da Grace was not only a widow but also a teacher).

- 6Atta Kwami, discussion with author, July 4, 2021.

- 7Ibid.

- 8Da Grace’s college art history course used the popular survey text Art through the Ages, which covers formal portraiture. The section on Non-European Art is comprised of seven chapters. Chapter 19 “Primitive (13th–20th Centuries)” begins pejoratively on page 632, “Primitive art is that produced by people who have no written literature, live in tribes, often still in a Neolithic cultural state” and then, in contradiction, describes the art of the kingdoms of Ife and Benin; it erroneously posits on page 633 that the Benin bronzes “were discovered by a British army expedition.” See Helen Gardner, Art through the Ages, ed. Sumner McKnight Crosby, 4th ed. (London: G. Bell and Sons, Ltd., 1959). Many years later, Da Grace recalled that “her art history course did not include modern art by Africans.” Atta Kwami, discussion with author, July 4, 2021.

- 9Atta Kwami, Kumasi Realism, 1951–2007: An African Modernism (London: Paul Hurst and Company, 2013), 28–32, 43.

- 10Da Grace to Elizabeth Brown, April 19, 1961, Grace Kwami File Box 89, Records of the Harmon Foundation, Inc. (1913–1967), Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

- 11For example, the price of her small “head” sculptures was higher in 1962 than in 1991; yet each receipt was less than fifteen dollars. Significant familial challenges included the death of her daughter, Attawa, in 1969, after which Da Grace transferred to Tamale Women’s Training College in northern Ghana (she returned to Ho in 1978), and during the 1980s, the absence of her well-educated sons, who were teaching in Nigerian colleges.

- 12Atta Kwami, Grace Kwami Sculpture (London: Royal College of Art, 1993); and Kwami, Kumasi Realism, 1951–2007.

- 13Nana Oforiatta Ayim, “Ghana Freedom,” in Ghana Freedom: Ghana Pavilion at the 58th International Art Exhibition; La Biennale di Venezia (London: König Books, 2019), 28. The Sankofa movement envisioned a distinctive Ghanaian modernism blending colonial/academic training with select African traditions. El Anatsui, a lecturer who taught art education using “Sankofa syndrome” at college level (1969–75), gives an excellent firsthand account. See El Anatsui, ‘‘Sankofa: Go Back an’ Pick’: Three Studio Notes and a Conversation,” Africa Special Issue, Third Text 7, no. 23 (1993): esp. 45 and 50–51. For Da Grace and Anatsui, both Ewé speakers, the Sankofa movement reprised an Ewé proverb—xoxo na wogbea yeye do—about growth that is critical in the oral literature about their forebears’ legendary story of migration, involving diplomacy and the efficacy of clay as an art material [the proverb’s translation is complex which why I have omitted it; ‘local’ understanding is contingent on awareness of the legend in Third Text above or Okwui Enwezor & Chika Okeke-Agulu. El Anatsui The Reinvention of Sculpture (2022, Damini),101. The simple version is “The new is woven on to the old”. N.K. Dzobo. African Proverbs Guide to Conduct The Moral Value of Ewe Proverbs (1973, University of Cape Coast), 73. Anatsui prefers a translation that is closer to the legend, ”It is on the sample of the old rope that one weaves the new one,” Anatsui 1993, 51; e-mail correspondence to the author, May 8, 2022.]

- 14Perrin Lathrop, “African Modernism in America. 1947–1967,” African Arts 54, no. 3 (Autumn 2021): 68–81.

- 15Antubam, Ghana’s Heritage of Culture, 82.

- 16Kwami, Grace Kwami Sculpture; and Atta Kwami, discussion with author, July 5, 2021.

- 17For further images and text, see “Grace Kwami Sculpture,” in “Artists’ Books and Africa,” Smithsonian Libraries website, https://library.si.edu/exhibition/artists-books-and-africa/grace-kwami-sculpture-full.

- 18See Grace Salome Kwami House facebook page, https://www.facebook.com/gracesalomekwamihouse/.