In December 1979, Lotty Rosenfeld created Una milla de cruces sobre el pavimento (A Mile of Crosses on the Pavement). Walking down a long road in eastern Santiago de Chile, Rosenfeld bisected the center-line markings through the perpendicular application of broad white tape. Executed at the height of the dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet, her defiant gesture generated a powerful new social sign: a path of crosses.

Following the dramatic aerial bombing and storming of the presidential Palacio de la Moneda (La Moneda Palace) in Santiago on the morning of September 11, 1973, a military junta led by General Augusto Pinochet toppled the government of Salvador Allende.1With Allende’s rise in 1970 as the world’s first democratically elected socialist president, a perceived new front in the global Cold War opened. From his first moments in office, Allende faced well-coordinated political opposition from conservative sectors of Chilean society, with covert support from abroad. When a series of general strikes starting in October 1972 did not cause the economic damage it was hoped would force Allende to resign, portions of the country’s military leadership began top-secret operational planning for a coup d’état. The Nixon administration was particularly anxious about developments in Chile, and the CIA implemented a strategy of operations code-named Project FUBELT, which was designed to undermine the Allende government. Documents detailing the project’s specific activities can be found online at the National Security Archive, the George Washington University. See Peter Kornbluh, “Chile and the United States: Declassified Documents Relating to the Military Coup, September 11, 1973,” National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book, no. 8. In the immediate aftermath of Allende’s overthrow, the military government began using coercive means to reshape all aspects of Chilean citizens’ lives.2During the months after Allende’s overthrow, the military began its persecution of citizens suspected of being leftists, eventually imprisoning an estimated forty thousand members of oppositional political parties at the Estadio Nacional (National Stadium) of Chile. In October 1973, a military convoy, which became known as the Caravana de la Muerte (Caravan of Death) crossed Chile, detaining and “disappearing” dissidents as well as establishing a reign of terror that would all but silence the opposition. Starting in 1975, the Pinochet regime also joined the military governments of Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Uruguay as members of Operación Condor (Operation Condor), a coordinated official program of political repression and intimidation intended to combat communist influence in the Southern Cone. A climate of fear overtook the nation’s public intellectual life, art institutions, and universities. Navigating the line between what could be said or seen, and what could not, was a risky proposition. Given the stakes of being perceived as critical of the government, many visual artists and writers engaged in a form of self-censorship. The challenges of negotiating a political climate of this type necessitated innovative tactics.

A set of new artistic practices slowly emerged among groups of Chilean visual artists, writers, and intellectuals—a confluence of critical theory and art practice later coined the escena de avanzada (the advanced scene) by Chilean cultural critic Nelly Richard.3Richard’s term for the Chilean neo-vanguard deliberately carries military connotations and invokes the western European historical avant-garde while still marking the new cultural ecosystem as specific to Chile’s contemporary sociopolitical realities. Her 1986 book Margins and Institutions: Art in Chile since 1973 was instrumental in shaping the international reception of the escena de avanzada. Nelly Richard, Margins and Institutions: Art in Chile since 1973 (Melbourne: Art & Text, [1986]). The Colectivo Acciones de Arte (Art Actions Collective), or CADA, was a central component of this neo-vanguard scene. Founded in 1979 by visual artists Lotty Rosenfeld (1943–2020) and Juan Castillo (born 1952), writer Diamela Eltit (born 1949), poet Raúl Zurita (born 1951), and sociologist Fernando Balcells (born 1950), the group dedicated itself to creating artworks open to interpretation by Chile’s fractured social body.4From the start, collaboration was central to CADA’s methods—whether in the form of collective artistic practice and authorship, the creation of works requiring an actively involved public, or the designation of the entire city of Santiago as an exhibition space. Though the name “CADA” (which translates as “each” or “every”) would seem to emphasize the importance of the individual, all of the group’s works were executed with a collective signature. CADA shared a philosophy that direct, regular engagement with art would transform the landscape into “a creative space that obligates one to remake their vision . . . and remake and question the surroundings.”5Unless otherwise noted, all translations are the author’s own. Diamela Eltit, “Sobre las acciones de arte: Un nuevo espacio crítico,” Umbral (Nuevo Época) 3 (1980); reprinted in Gaspar Galaz and Milan Ivelić, Chile, arte actual (Valparaíso: Ediciones Universitarias de Valparaíso, Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, 1988), 52. This orientation toward articulating a poetics of politics played out in conversations between the group members’ individual visual and literary projects and the collective’s public art actions.6The collective’s four public actions Para no morir de hambre en el arte (So as Not to Die of Hunger in Art), October 3, 1979; Inversión de escena (Scene Inversion), October 17, 1979; ¡Ay Sudamérica! (Oh South America!), July 12, 1981; NO +, 1983; and its “press-action” Viuda (Widow), 1985, form the core of the group’s production. CADA’s “video-actions” So as Not to Die of Hunger in Art, Scene Inversion, and Oh South America! are part of MoMA’s collection, acquired following their inclusion in curator Barbara London’s 1981 exhibition Video from Latin America.

In December 1979, Lotty Rosenfeld’s Una milla de cruces sobre el pavimento (A Mile of Crosses on the Pavement) moved the space of art further into the street to establish closer contact with daily life. Walking down a long road in eastern Santiago, Rosenfeld bisected the center-line markings through the perpendicular application of broad white tape. Her gesture generated a powerful new social sign: a path of crosses.7The performance of Una milla de cruces sobre el pavimento was carried out clandestinely over a period of four hours on Avenida Manquehue Norte in proximity to the Escuela Militar del Libertador Bernardo O’Higgins, the national military school. The action was captured on 16mm film and then transferred to video, where it was edited. The version of the video now in MoMA’s collection opens with an image of a two-lane road, and the audio “No, no fui feliz” (No, I wasn’t happy).8This phrase might be read as a response to the contemporary development of Alfredo Jaar’s project Estudios sobre la felicidad (Studies on Happiness), 1979–81, in which the artist engaged the public on the sidewalks in central Santiago with a series of surveys in June, August, and September 1980. His questions gauged respondents’ perceptions of their own personal happiness, as well as the happiness of their fellow Chileans and of citizens of other countries. In September 1981, billboards bearing the simple question “¿ES USTED FELIZ?” (Are you happy?) in a bold sans-serif black font on a flat white field began to appear around the city and its outskirts. The phrase also recurs throughout Rosenfeld’s artist’s book Una milla de cruces sobre el pavimento (Santiago: Ediciones C.A.D.A., 1980), both graphically and in “Congestionamientos,” (“Congestions”), a textual analysis of the art action authored by Eltit and critic Eugenia Brito. Rosenfeld signs her name on the pavement with a piece of chalk, thereby activating the road as an art space, and transforming the results of her action upon it into a work of public art. The camera begins to travel down the road in the right lane, with the occasional car passing it in the left. The artist repeats the gesture: gluing down the left edge with a paintbrush from a can of Pegafix adhesive, unfurling the roll of tape to the right, smoothing it, and then tacking down the right edge with glue.

In a handwritten artist’s statement included in an artist’s book published in May 1980, Rosenfeld explains that “a mile of crosses on the pavement is for me a way of presenting our bodies violating the functional inertia of their paths.”9Artist’s statement in Una milla de cruces sobre el pavimento, 28–29 If transit signs represent the status quo, then cancelling them signals an act of resistance. While invoking the Christian symbolism of the cross and the implication of pain,10Against the sociocultural backdrop of Pinochet’s Chile, the Christian symbolism of the white “+” is amplified. Promoting traditional Catholic values, the regime sought to reposition women as the emotional and spiritual anchors of the family and home. Rosenfeld’s action subverts this ideology, rejecting it by performing the sign of the cross out in the world. the line of crosses could also be read as a series of + signs, or as “waiting for the result of the addition of its members,” as Diamela Eltit explains.11Eltit, “Sobre las acciones de arte,” 53. This kind of mark-making carries the potential to symbolically reclaim an empty or neglected space, and the inscription of such marks on a cityscape seeks to make visible the overlooked and the repressed. Meanwhile, the act of applying the crosses to the road is also reminiscent of bandaging or closing a wound. At once both locating and dislocating, the openness of Rosenfeld’s + signs allowed the work to be translated to and repeated at locations across Chile and around the world.12Perhaps the most iconic image of the ongoing “+” series shows Rosenfeld unfurling a roll of the white tape to the north of the Palacio de la Moneda (October–November 1984). Capturing the artist’s emphatic action, the resulting film still and photograph encapsulate the power of the sign. As a gesture intended to expose the dynamics of power on both the national and international scales, Rosenfeld also staged actions at the sites of cultural power, such as at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes (October–November 1984), on international borders such as the Christ the Redeemer Tunnel between Chile and Argentina (April 1983), and at a crossing point between East and West Berlin (June 1983), as well as at sites of cultural, economic, and political power around the world, including Revolution Square in Havana (1985), court buildings in Buenos Aires (December 1985), the capitol building in San Juan, Puerto Rico (1994), and the Bank of England in London (1996).

In performing this simple, provocative gesture for the photographer and cinematographer, Rosenfeld ensured the future circulation of the critical event. A video installation, mounted in June 1980 in the original location of the intervention, included two giant video monitors and a movie screen, which projected looped footage of the performance, or “actions of actions,” as Rosenfeld has described it.13Lotty Rosenfeld, Lotty Rosenfeld: Antología digital, 1979–2003, DVD 1, liner notes, 3. The documentary photographs and video footage function as a trace and a record of the action, both “an accusing reference”14Eltit, “Sobre las acciones de arte,” 52–53. and a solution to the problem of preserving and transmitting the actions to a wider audience. By “prolonging the gesture,” as Richard proposes, video could be instrumentalized as a new “model of disobedience.”15Nelly Richard, “Resta de sentido,” in Desacato: sobre la obra de Lotty Rosenfeld, eds. María Eugenia Brito et al. (Santiago: Francisco Zegers, 1986), 21–22.

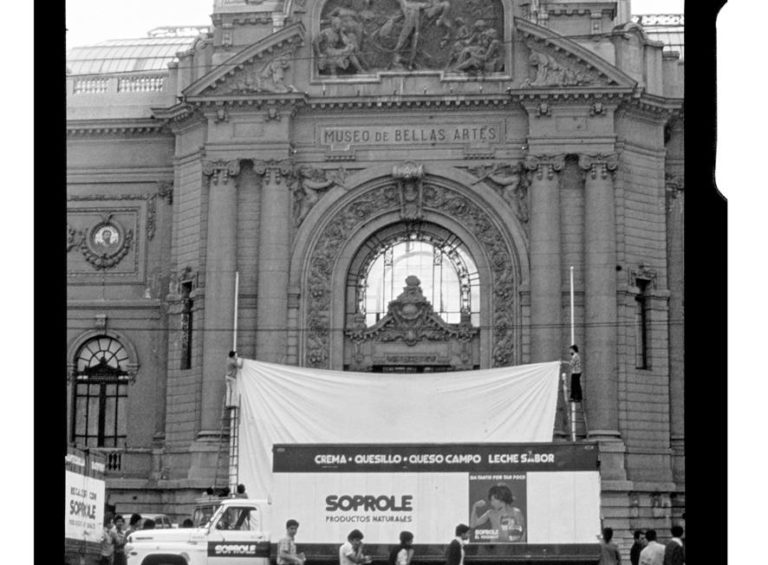

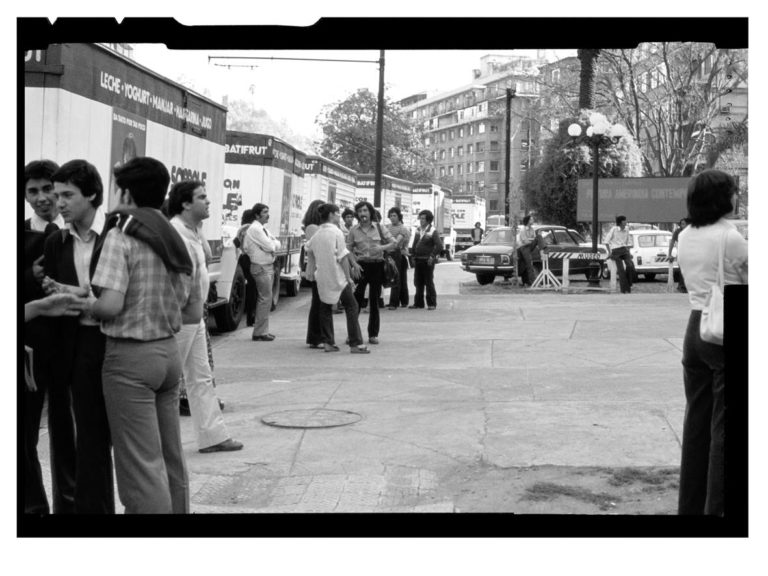

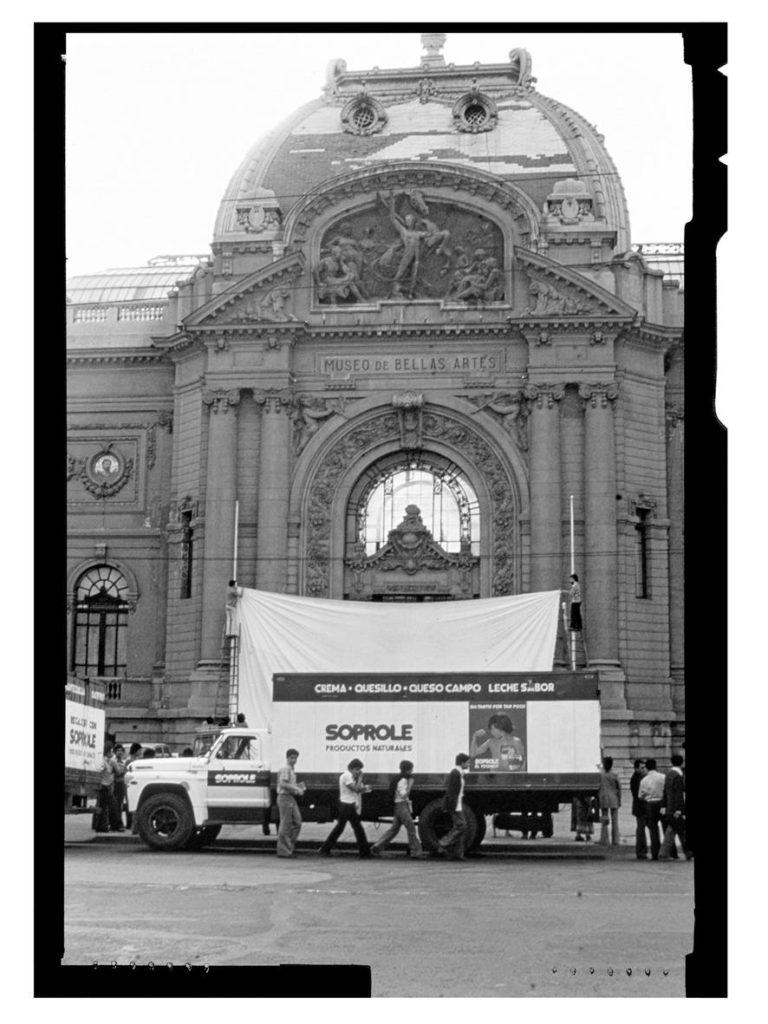

On October 17, 1979, two months before Rosenfeld executed her avenue intervention, CADA staged Inversión de escena (Scene Inversion)—one of three of the collective’s acciones de arte in MoMA’s collection. Orchestrating a procession of ten milk trucks through the streets of Santiago, the event evoked—as Raúl Zurita has suggested—the martial image of an advancing tank brigade.16Raúl Zurita proposed this reading in an interview with Robert Neustadt. Robert Alan Neustadt, CADA día: la creación de un arte social (Santiago: Cuarto Propio, 2001), 79–80. The trucks moved as a unit, attempting not to be separated by traffic signals, until they reached the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes (National Museum of Fine Arts), where they parked in a line. Upon their arrival at the museum, the group’s members proceeded to unfurl an enormous white sheet and hoist it up the flagpoles flanking the steps leading to the main entrance. Effectively blocking access to the institution, the white sheet served as a metaphoric blank canvas, or movie screen waiting to be filled with shadows from passersby or the moving images of life. This inverted scene insists that the real contemporary art is to be found in the streets of the city.17During the installation, a television monitor in the back of one of the trucks replayed video footage shot as the caravan traveled to the museum, delivering nearly simultaneous documentation of the performance to interested passersby.

Rosenfeld continued the line of investigation established in Una milla de cruces sobre el pavimento with an art action at The White House in Washington, DC in June 1982, when she traced a white cross in the street facing the building’s south facade. The process was photographed and filmed, documenting the transplantation of the + sign to a North American context.18This footage was incorporated into her 1982 video work Una herida americana (An American Wound), which was screened as part of her art action Bolsa de Comercio de Santiago at the Santiago Stock Exchange that same year. Installed on two video monitors on the central desk of the exchange, An American Wound played as preoccupied traders engaged with the day’s urgent financial transactions. The piece featured two groups of images: video documentation of the artist’s action on the Pan-American Highway in the Atacama Desert in northern Chile and photographic documentation of the action in front of the White House. In a statement for the project, Rosenfeld describes how the work draws “an imaginary line between these points, a line susceptible to being seen not only as a wound I suture in an exemplary way but [one] that will heal only with the advent of another history. I suggest this as an aesthetic proposition, thinking of the alteration of the totality of signs as a collective construction of social happiness.” Lotty Rosenfeld, artist’s statement in “Una herida americana,” May 15, 1982, in Textos por Latinoamérica, Serie Cuadernos Marginales (Santiago: Talleres del Mar, 1982), n.p.

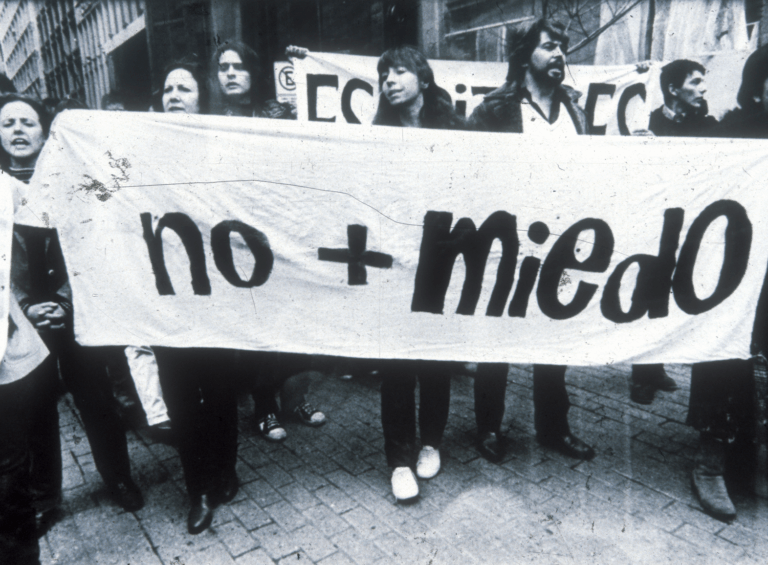

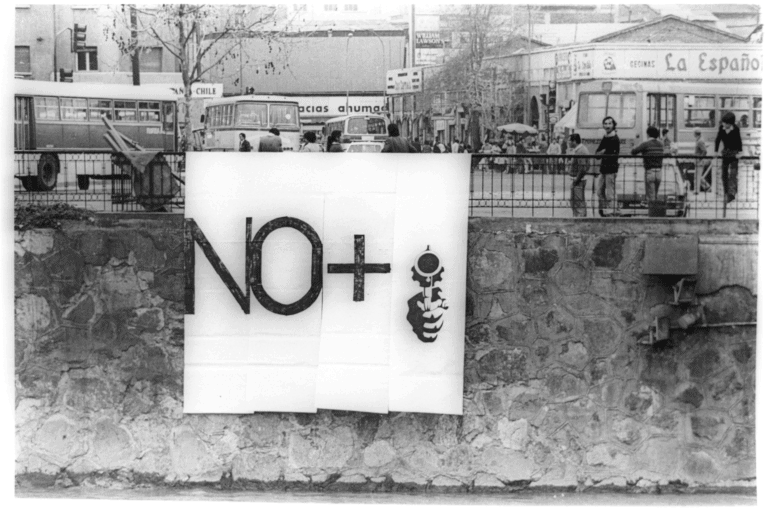

Recognizing the visual power of Rosenfeld’s + sign and the poetry of multivalent social gestures, CADA launched its most politically effective intervention in 1983. Thoroughly blurring the line between art and politics, NO + (No más / No more) was conceived in the tenth year of the military dictatorship. Invoking the legacy of the Chilean mural painting brigades of the late 1960s and early ’70s, the action began in late 1983 and continued into early 1984, when artist collaborators painted the text “NO +” on walls in neighborhoods across Santiago. This graphic was completed by residents, as an anonymous outlet for their discontent with the repressive policies of the military government. The text quickly became ubiquitous as a rallying cry for Chile’s burgeoning pro-democracy movement. In the period leading up to the 1988 referendum on Pinochet’s rule, “NO +” was adopted by resistance groups all over the country.

The referendum on October 5 of that year on whether Pinochet should govern another eight years was won by the “No” side, with approximately 56 percent of the vote. Presidential and parliamentary elections were held in December 1989, and the opposition candidate Patricio Aylwin entered office on March 11, 1990, ending the Pinochet regime’s nearly seventeen years in power. For more than a decade after their original appearance in Santiago, Lotty Rosenfeld’s crosses reinforced her own statements about them as “calls to attention,” offering “a thousand horizons unfurled until their relevance is used and vanishes.”19Artist’s statement in Una milla de cruces sobre el pavimento, 28–29. By repeating the crossings “as personal and collective works of transformation of the social landscape imaginary,”20Ibid. Rosenfeld and CADA’s art actions encapsulated the spirit of opposition to authoritarianism, evolving into tools that helped Chile’s citizens express their dissent, and a poetico-political power that persists today.

- 1With Allende’s rise in 1970 as the world’s first democratically elected socialist president, a perceived new front in the global Cold War opened. From his first moments in office, Allende faced well-coordinated political opposition from conservative sectors of Chilean society, with covert support from abroad. When a series of general strikes starting in October 1972 did not cause the economic damage it was hoped would force Allende to resign, portions of the country’s military leadership began top-secret operational planning for a coup d’état. The Nixon administration was particularly anxious about developments in Chile, and the CIA implemented a strategy of operations code-named Project FUBELT, which was designed to undermine the Allende government. Documents detailing the project’s specific activities can be found online at the National Security Archive, the George Washington University. See Peter Kornbluh, “Chile and the United States: Declassified Documents Relating to the Military Coup, September 11, 1973,” National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book, no. 8.

- 2During the months after Allende’s overthrow, the military began its persecution of citizens suspected of being leftists, eventually imprisoning an estimated forty thousand members of oppositional political parties at the Estadio Nacional (National Stadium) of Chile. In October 1973, a military convoy, which became known as the Caravana de la Muerte (Caravan of Death) crossed Chile, detaining and “disappearing” dissidents as well as establishing a reign of terror that would all but silence the opposition. Starting in 1975, the Pinochet regime also joined the military governments of Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Uruguay as members of Operación Condor (Operation Condor), a coordinated official program of political repression and intimidation intended to combat communist influence in the Southern Cone.

- 3Richard’s term for the Chilean neo-vanguard deliberately carries military connotations and invokes the western European historical avant-garde while still marking the new cultural ecosystem as specific to Chile’s contemporary sociopolitical realities. Her 1986 book Margins and Institutions: Art in Chile since 1973 was instrumental in shaping the international reception of the escena de avanzada. Nelly Richard, Margins and Institutions: Art in Chile since 1973 (Melbourne: Art & Text, [1986]).

- 4From the start, collaboration was central to CADA’s methods—whether in the form of collective artistic practice and authorship, the creation of works requiring an actively involved public, or the designation of the entire city of Santiago as an exhibition space. Though the name “CADA” (which translates as “each” or “every”) would seem to emphasize the importance of the individual, all of the group’s works were executed with a collective signature.

- 5Unless otherwise noted, all translations are the author’s own. Diamela Eltit, “Sobre las acciones de arte: Un nuevo espacio crítico,” Umbral (Nuevo Época) 3 (1980); reprinted in Gaspar Galaz and Milan Ivelić, Chile, arte actual (Valparaíso: Ediciones Universitarias de Valparaíso, Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, 1988), 52.

- 6The collective’s four public actions Para no morir de hambre en el arte (So as Not to Die of Hunger in Art), October 3, 1979; Inversión de escena (Scene Inversion), October 17, 1979; ¡Ay Sudamérica! (Oh South America!), July 12, 1981; NO +, 1983; and its “press-action” Viuda (Widow), 1985, form the core of the group’s production. CADA’s “video-actions” So as Not to Die of Hunger in Art, Scene Inversion, and Oh South America! are part of MoMA’s collection, acquired following their inclusion in curator Barbara London’s 1981 exhibition Video from Latin America.

- 7The performance of Una milla de cruces sobre el pavimento was carried out clandestinely over a period of four hours on Avenida Manquehue Norte in proximity to the Escuela Militar del Libertador Bernardo O’Higgins, the national military school.

- 8This phrase might be read as a response to the contemporary development of Alfredo Jaar’s project Estudios sobre la felicidad (Studies on Happiness), 1979–81, in which the artist engaged the public on the sidewalks in central Santiago with a series of surveys in June, August, and September 1980. His questions gauged respondents’ perceptions of their own personal happiness, as well as the happiness of their fellow Chileans and of citizens of other countries. In September 1981, billboards bearing the simple question “¿ES USTED FELIZ?” (Are you happy?) in a bold sans-serif black font on a flat white field began to appear around the city and its outskirts. The phrase also recurs throughout Rosenfeld’s artist’s book Una milla de cruces sobre el pavimento (Santiago: Ediciones C.A.D.A., 1980), both graphically and in “Congestionamientos,” (“Congestions”), a textual analysis of the art action authored by Eltit and critic Eugenia Brito.

- 9Artist’s statement in Una milla de cruces sobre el pavimento, 28–29

- 10Against the sociocultural backdrop of Pinochet’s Chile, the Christian symbolism of the white “+” is amplified. Promoting traditional Catholic values, the regime sought to reposition women as the emotional and spiritual anchors of the family and home. Rosenfeld’s action subverts this ideology, rejecting it by performing the sign of the cross out in the world.

- 11Eltit, “Sobre las acciones de arte,” 53.

- 12Perhaps the most iconic image of the ongoing “+” series shows Rosenfeld unfurling a roll of the white tape to the north of the Palacio de la Moneda (October–November 1984). Capturing the artist’s emphatic action, the resulting film still and photograph encapsulate the power of the sign. As a gesture intended to expose the dynamics of power on both the national and international scales, Rosenfeld also staged actions at the sites of cultural power, such as at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes (October–November 1984), on international borders such as the Christ the Redeemer Tunnel between Chile and Argentina (April 1983), and at a crossing point between East and West Berlin (June 1983), as well as at sites of cultural, economic, and political power around the world, including Revolution Square in Havana (1985), court buildings in Buenos Aires (December 1985), the capitol building in San Juan, Puerto Rico (1994), and the Bank of England in London (1996).

- 13Lotty Rosenfeld, Lotty Rosenfeld: Antología digital, 1979–2003, DVD 1, liner notes, 3.

- 14Eltit, “Sobre las acciones de arte,” 52–53.

- 15Nelly Richard, “Resta de sentido,” in Desacato: sobre la obra de Lotty Rosenfeld, eds. María Eugenia Brito et al. (Santiago: Francisco Zegers, 1986), 21–22.

- 16Raúl Zurita proposed this reading in an interview with Robert Neustadt. Robert Alan Neustadt, CADA día: la creación de un arte social (Santiago: Cuarto Propio, 2001), 79–80.

- 17During the installation, a television monitor in the back of one of the trucks replayed video footage shot as the caravan traveled to the museum, delivering nearly simultaneous documentation of the performance to interested passersby.

- 18This footage was incorporated into her 1982 video work Una herida americana (An American Wound), which was screened as part of her art action Bolsa de Comercio de Santiago at the Santiago Stock Exchange that same year. Installed on two video monitors on the central desk of the exchange, An American Wound played as preoccupied traders engaged with the day’s urgent financial transactions. The piece featured two groups of images: video documentation of the artist’s action on the Pan-American Highway in the Atacama Desert in northern Chile and photographic documentation of the action in front of the White House. In a statement for the project, Rosenfeld describes how the work draws “an imaginary line between these points, a line susceptible to being seen not only as a wound I suture in an exemplary way but [one] that will heal only with the advent of another history. I suggest this as an aesthetic proposition, thinking of the alteration of the totality of signs as a collective construction of social happiness.” Lotty Rosenfeld, artist’s statement in “Una herida americana,” May 15, 1982, in Textos por Latinoamérica, Serie Cuadernos Marginales (Santiago: Talleres del Mar, 1982), n.p.

- 19Artist’s statement in Una milla de cruces sobre el pavimento, 28–29.

- 20Ibid.