A trailblazing figure in the Southern Cone art scene of the middle decades of the 20th century, Yente (Eugenia Crenovich) has, until recently, received little recognition for her critical contributions to abstraction in Argentina. This essay discusses the context in which the artist realized one of her most unusual pieces, Object (1946), a work of art that defies clear alignment with either painting or sculpture.

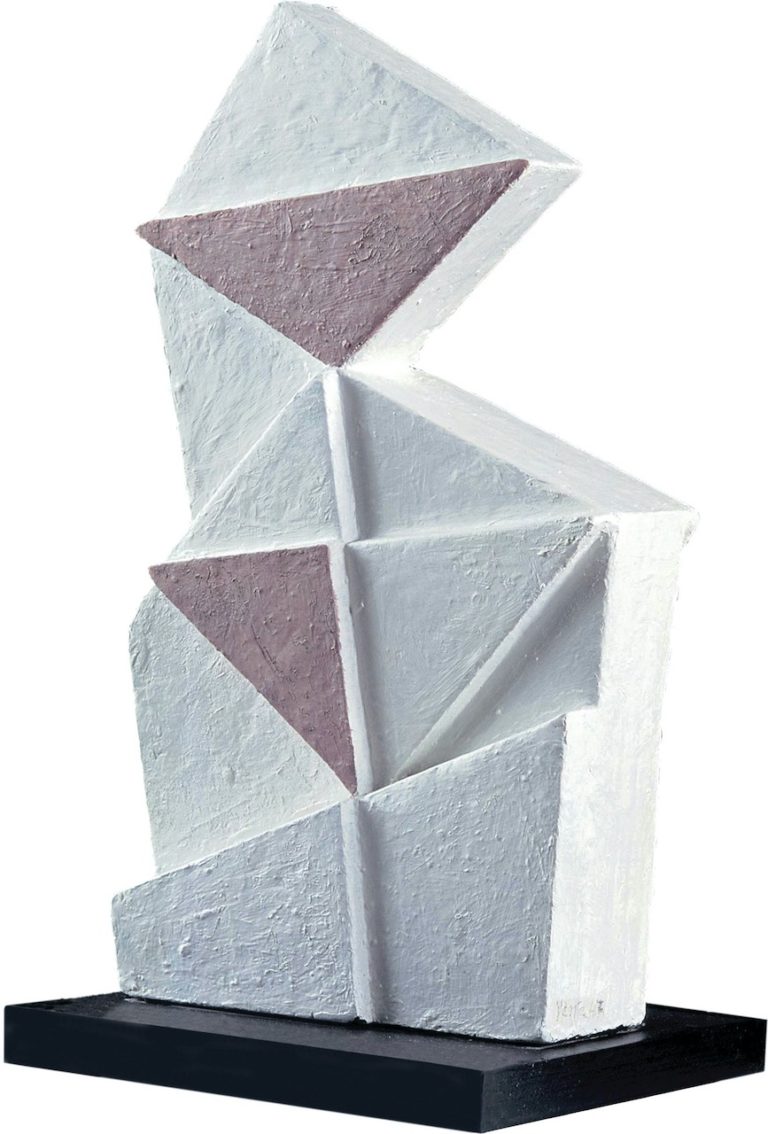

In Yente’s intriguing Object from 1946 (fig. 1), viewers are faced with an unusual presence. A sculptural form made from mixed media, this small-scale white object presents a surface that has been worked into irregular geometric planes that intersect to disorient the gaze. Upon further investigation, this work unfolds a history that reveals Yente’s position as a trailblazing figure in the Southern Cone art scene of the middle decades of the 20th century.

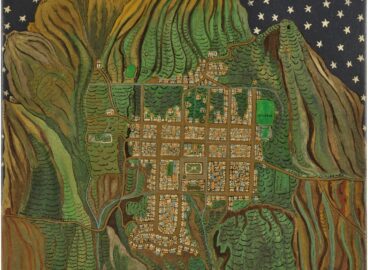

The life and career of Argentine artist Eugenia Crenovich, known as Yente (1905–1990), has always been entangled with that of artist Juan Del Prete (1897–1987), her partner beginning in 1935 (fig. 2). This omnipresent association has obscured her long trajectory in the Latin American art scene. Like other women artists working within abstract languages, such as Anita Payró (1897–1980), Yente wanted to publicly claim her role as a pioneer in developing new forms of visual expression, but she ultimately refrained from doing so. Scholar Adriana Lauría has noted that Yente often wrote letters to art historians and curators, most of which she never sent. From these detailed writings, in which she states the early dates of her abstract pieces, it is clear that Yente played a critical role in advancing abstraction in Argentina.1Adriana Lauría, “Yente. Una pionera en los márgenes,” in Yente-Prati, ed. Adriana Lauría, exh. cat. (Buenos Aires: Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires, 2009), 17.

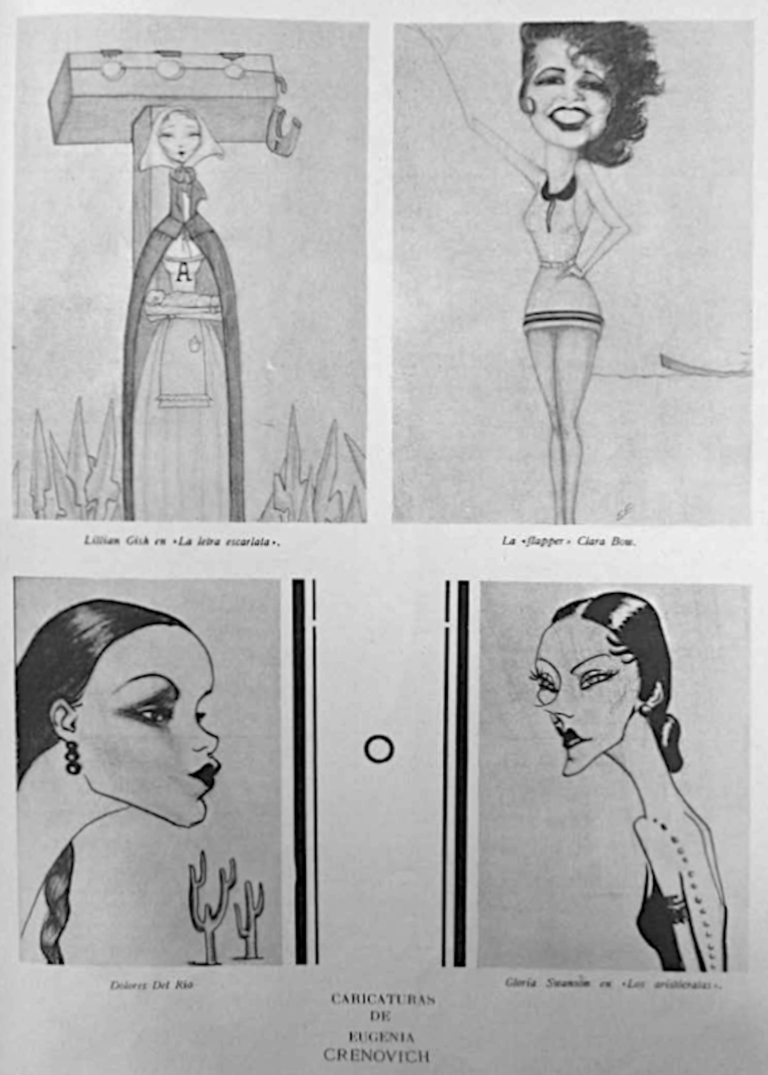

Yente spent the late 1920s and early 1930s between Buenos Aires and Santiago de Chile, two modern, bustling cities in the Southern Cone. It was there that she simultaneously studied philosophy and art. Her first known works are magazine illustrations that range from caricatures of movie stars (fig. 3) to images of working-class mothers (fig. 4). Published in Máscaras and La Mujer Nueva, these early works reveal two fundamental traits of Yente’s practice: a constant challenging of traditional artistic boundaries and an engagement with alternative networks of circulation. Working at the interstices of painting and graphic art, painting and sculpture, abstraction and figuration, and traditional and nontraditional materials, Yente’s work shifted and changed endlessly.

She first met Del Prete in 1935, and this encounter opened new creative paths for both artists. Yente would remember the episode more than forty years later: “It was a fundamental event for me: it was the first time that I came into contact with the work of a creator.”2Raúl Vera Ocampo, “La obra libre,” La Opinión Cultural, August 19, 1979, 8, http://www.cvaa.com.ar/02dossiers/yente/07_anto_1979_5a.php. All translations are my own. While her relationship with Del Prete would allow her to form lasting associations in a milieu that favored married over single women, many considered her to be simply a disciple of her more recognized partner.3In Argentina, the “official” history of abstract art of recent times includes only a handful of women. Artists such as Yente and Lidy Prati (1921–2008), who married Tomás Maldonado (1922–2018) in 1942, have been subjects of exhibitions. These two women artists share the fact that they were both married to much more visible male artists. Being associated with major male figures in the art world helped both women to participate in the prestigious and often avant-garde exclusive art networks. For example, in his memoirs, artist Juan Melé (1923–2012) rarely mentions Yente and Prati on their own. Juan N. Melé, La vanguardia del 40. Memorias de un artista concreto (Buenos Aires: Ediciones Cinco), 1999. Moreover, art critics often discussed the work of married women only alongside that of their husbands, suggesting women artists would have been overlooked had they not been married. See Damián Carlos Bayón, “Arte abstracto, concreto, no figurativo,” Ver y Estimar (September 1948): 62. However, she contradicted this understanding in an interview: “His work was a lesson to me, although he was never my teacher. His lesson was his work.”4Raúl Vera Ocampo, “La obra libre,” 8.

After her first solo show, an exhibition that included figurative drawings, held in 1935 at the Amigos de Arte cultural space, Yente began her experiments with abstraction through the medium of painting (fig. 5). She connected this radical change to her relationship with Del Prete, writing: “From 1937, I joined Del Prete in his fight for nonfigurative art.”5Yente to Ernesto B. Rodríguez, January 12, 2021, in Yente, Anotaciones para una semblanza de Juan Del Prete (Rosario: Iván Rosado, 2019), 74. In her first ventures, she often utilized poster paint (fig. 6)—a medium commonly used in primary school art classes and far removed from the so-called fine arts tradition—along with hardboard, cardboard, and paper as modest supports. In the early 1940s, Yente also began working with composite wood, an industrial derivative of the natural material. Easy to carve with simple tools, this medium an ideal vehicle to create simple yet compelling structures.

At the Buenos Aires–based Galería Müller in 1945, Yente presented works she had made between 1937 and 1945. Most importantly for the present text, in that exhibition, she included her relieves (reliefs) and corpóreos (corporeal objects). Painting, relief, and sculpture convene in these strange objects that defied traditional artistic labels of the time, destabilizing the tranquility of the exhibition halls of the gallery. These series of works confused art critics. The exhibition reviews, such as those published in the influential newspapers La Nación and La Prensa, evidence the shock experienced by art critics when they encountered Yente’s latest works. Argentine writer Vizconde Lascano Tegui (1887–1966) expresses his hesitations regarding them: “The exhibition room is presented as a laboratory and not as a workshop.”6Vizconde Lascano Tegui, “Eugenia Crenovich,” El Mundo, October 4, 1945, 17, http://www.cvaa.com.ar/02dossiers/yente/07_anto_1945_1a.php. An anonymous critic writes: “The result [of all the works displayed] gives us a kaleidoscopic impression that we must sort out ourselves.”7“Exposición de Eugenia Crenovich,” La Prensa, October 15, 1945, http://www.cvaa.com.ar/02dossiers/yente/07_anto_1945_3a.php By challenging the constructive and machine-made aesthetic of Concrete Art, a dominant mode of abstraction in Argentina at the time, and by disrupting categorical divisions of media, the artist uncovered a new arena for creative investigation. Nevertheless, she received little critical recognition.

While Yente made Object in 1946, the year after her controversial exhibition at Galería Müller, the relieves and corpóreos clearly foreshadow the piece. A distinctly human-made work of art, yet defying clear alignment with either sculpture or painting, Object can be understood in the contexts of experimentation and the art-making process. It was first presented publicly in 1946 when Yente held a second solo exhibition at the Galería Müller, this one encompassing only nonfigurative works. In an article published the same year, writer and art critic Romualdo Brughetti (1912–2003) expresses a nuanced and informed vision of Yente’s practice, one that offers an overview of the abstract currents in Argentina and includes a reproduction of one of Yente’s relieves (which, accordingly, was incorrectly labeled as a painting). Brughetti depicts the artist as an independent figure connected to well-known artist groups including Asociación Arte Concreto-Invención and Arte Madí thanks to a shared interest in abstraction but as nonetheless clearly autonomous in her artistic explorations.

Additionally, Brughetti praises her “pinturas en relieve” (relief paintings) and her sculptures,8Romualdo Brughetti, “Un mundo más puro y sencillo. El arte abstracto en la Argentina,” Cabalgata, November 19, 1946, 6. employing traditional and nontraditional artistic terminology, a clear sign of the challenges Yente’s works posed to art criticism. In fact, Yente herself developed her own terminology for her art. In 1962, she wrote about the works on display in these exhibitions of the mid-1940s as “abstract reliefs and some sculptures I called Objects.”9Yente to Rodríguez, January 12, 2021, in Yente, Anotaciones, 75. MoMA’s piece is a rare example of this series of Objects (figs. 7–9): a nonfigurative sculpture reminiscent of a relief, with empty spaces in the bottom and bereft of a pedestal separating it from viewers, Object is still as captivating as ever.

Throughout her life, Yente would present her works in a variety of contexts, using every possible space to display her vision. National, provincial, and even municipal salons, such as the Salón de Arte de Mar del Plata, attracted her attention. A fiercely independent artist, Yente rightfully claimed for herself the status of a pioneer of abstract art, a fact that is just beginning to be acknowledged. Moreover, her involvement with textile art from the 1950s shows another side of her career. Yente’s Tapestry no. 6 (1958), with its connection to informalist aesthetics, shows layers of color, both painted and embroidered. This series of textile works connects Yente with a genealogy of women artists interested in creating environments with modern objects and re-signifying the domain of decorative arts.10Contemporaries such as Sonia Delaunay (1885–1979), Marion Dorn (1899–1964), and Anni Albers (1899–1994) devoted themselves to the creation of objects, textiles, and clothing. Whether working on wood or wool, Yente continued to expand the concept of art, all the while surprising viewers.

- 1Adriana Lauría, “Yente. Una pionera en los márgenes,” in Yente-Prati, ed. Adriana Lauría, exh. cat. (Buenos Aires: Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires, 2009), 17.

- 2Raúl Vera Ocampo, “La obra libre,” La Opinión Cultural, August 19, 1979, 8, http://www.cvaa.com.ar/02dossiers/yente/07_anto_1979_5a.php. All translations are my own.

- 3In Argentina, the “official” history of abstract art of recent times includes only a handful of women. Artists such as Yente and Lidy Prati (1921–2008), who married Tomás Maldonado (1922–2018) in 1942, have been subjects of exhibitions. These two women artists share the fact that they were both married to much more visible male artists. Being associated with major male figures in the art world helped both women to participate in the prestigious and often avant-garde exclusive art networks. For example, in his memoirs, artist Juan Melé (1923–2012) rarely mentions Yente and Prati on their own. Juan N. Melé, La vanguardia del 40. Memorias de un artista concreto (Buenos Aires: Ediciones Cinco), 1999. Moreover, art critics often discussed the work of married women only alongside that of their husbands, suggesting women artists would have been overlooked had they not been married. See Damián Carlos Bayón, “Arte abstracto, concreto, no figurativo,” Ver y Estimar (September 1948): 62.

- 4Raúl Vera Ocampo, “La obra libre,” 8.

- 5Yente to Ernesto B. Rodríguez, January 12, 2021, in Yente, Anotaciones para una semblanza de Juan Del Prete (Rosario: Iván Rosado, 2019), 74.

- 6Vizconde Lascano Tegui, “Eugenia Crenovich,” El Mundo, October 4, 1945, 17, http://www.cvaa.com.ar/02dossiers/yente/07_anto_1945_1a.php.

- 7“Exposición de Eugenia Crenovich,” La Prensa, October 15, 1945, http://www.cvaa.com.ar/02dossiers/yente/07_anto_1945_3a.php

- 8Romualdo Brughetti, “Un mundo más puro y sencillo. El arte abstracto en la Argentina,” Cabalgata, November 19, 1946, 6.

- 9Yente to Rodríguez, January 12, 2021, in Yente, Anotaciones, 75.

- 10Contemporaries such as Sonia Delaunay (1885–1979), Marion Dorn (1899–1964), and Anni Albers (1899–1994) devoted themselves to the creation of objects, textiles, and clothing.