In Campesinos Testifying, Palace of Justice, Cuzco (c. 1929) by Peruvian photographer Martín Chambi (1891–1973), six Andean peasants huddle together at the Cuzco courthouse—four on a wooden bench and two standing behind them. Behind this group, two men are seated along a wall and, to their right, two functionaries sit at a table, one bent over his paperwork. Receding into the background of the room, these four men in suits underscore the peasants’ incongruous presence in a government office. The stripes of their rough ponchos contrast with the faded floral carpet beneath their bare feet. Bearing expressions that flicker from impassive to imploring, obdurate to contrite, the peasants meet the camera’s lens with serious gazes. Scant information about this arresting—and possibly arrested—group exists beyond the title of the photograph. Who are these people and what brought them to court? The image alone provides no answer.

Active between 1908 and 1954, Chambi photographed widely in the southern Andes of Peru, achieving significant renown in his own day. Born to an Indigenous family in a small highland town in the province of Puno, Chambi was a native speaker of Quechua, the most common Indigenous language spoken in the Andes. His skill behind the camera afforded him social mobility in a region riven by racial and economic inequality. Having first laid eyes on the apparatus as a teenager outside the gold mine where his late father had labored, Chambi apprenticed with the photographer Max T. Vargas (1874–1959) in Arequipa before opening his own photography studio in Cuzco. There, in the former Inca capital, Chambi made portraits of the middle and upper classes; shot scenes of urban and rural life in the city and its surroundings; and documented architectural and archaeological sites. At the time of his death in 1973, Chambi’s archive contained some thirty thousand negatives; in 1978, his son Víctor Chambi, collaborated with U.S. photographer Edward Ranney (born 1942) on a restoration project. The following year, in 1979, they selected a group of negatives to reprint for an exhibition that traveled to The Museum of Modern Art and subsequently entered MoMA’s collection.1Projects: Martín Chambi and Edward Ranney was on view at MoMA from March 23 to May 3, 1979.

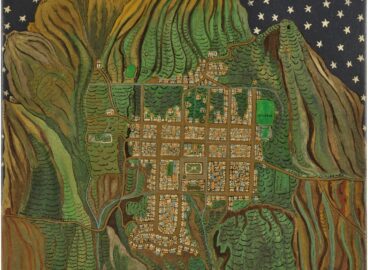

Campesinos Testifying is presently on view at the Museum in a collection gallery related to Indigenism, a movement of considerable cultural and political influence across Latin America in the early twentieth century that sought to redress the oppression of Indigenous peoples. The Peruvian Marxist critic José Carlos Mariátegui offered one of the first literary theories of Indigenism, describing it as an emergent yet transitional genre, as a prerequisite for a future literature written by and for Indigenous people. “Indigenist literature cannot give us a rigorously veristic version of the indio,” he wrote, in the parlance of the time. “It must idealize and stylize the indio. Nor can it give us its proper spirit, for it is still a literature of mestizos.”2“La literatura indigenista no puede darnos una versión rigurosamente verista del indio. Tiene que idealizarlo y estilizarlo. Tampoco puede darnos su propia ánima. Es todavía una literatura de mestizos. Por eso se llama indigenista y no indígena.” José Carlos Maríategui, Siete Ensayos de Interpretación de la Realidad Peruana (1928; Barcelona: Linkgua, 2009), 288. In these few lines Mariátegui makes two foundational observations about Indigenist art: first, that Indigenism is the prerogative of non-Indigenous or mixed-race intellectuals; second, that it aspires to representation but not realism. As an artist of Indigenous heritage and a photographer, Chambi challenged these precepts, even collaborating with Indigenist intellectuals who often chose or commissioned his work to illustrate their writings.3For a thorough analysis of Chambi’s relationship to Indigenism, see Natalia Majluf, “Martín Chambi: Fotografía e Indigenismo,” in Chambi, ed. Natalia Majluf and Edward Ranney, exh. cat. (Lima: Museo de Arte de Lima, 2015), 274–93. Deborah Poole has shown how photographic technologies are inextricable from the construction of race in the Peruvian Andes. See Poole, Vision, Race, and Modernity: A Visual Economy of the Andean World (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997). A photograph like Campesinos Testifying, which has lost the original context of its production, demonstrates how Chambi’s work might speak for itself.

Campesinos Testifying pictures a trial, but researchers have yet to find written records that, corresponding to the event, confirm whether the peasants were defendants or plaintiffs. Literary historian Jorge Coronado located a descendant of one lawyer pictured in the photograph,who alleged that the peasants were on trial for attempting to assassinate a powerful landowner.4Jorge Coronado, The Andes Imagined: Indigenismo, Society, and Modernity, (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburg Press, 2009), 160. Uprisings plagued plantations and farms in Peru’s rural provinces throughout the 1920s, and the press sensationalized particularly violent episodes, stoking elites’ fears of revolution.5For a history of early twentieth-century uprisings in the southern Andes, see José Deustua and José Luis Rénique, “Indigenistas y Movimientos Campesinos en el Cusco, 1918–1923,” in Intelectuales, indigenismo y descentralismo en el Perú, 1897–1931 (Cuzco: Centro de Estudios Regionales Andinos “Bartolomé de las Casas,” 1984): 69–92; and Wilfredo Kapsoli and Wilson Reátegui, El campesinado peruano: 1919–1930 (Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, 1972). But Andean peasants also employed nonviolent methods as they resisted the exploitation of their labor and dispossession of their lands under the feudal structure of the agricultural economy. They petitioned local and federal authorities, for example, attempting to claim rights granted by the 1920 constitution, in which the state first legally recognized Indigenous communities—even as the justice system proved inadequate in the face of the political influence of wealthy landowners.6Indigenous activist Miguel Quispe, for example, used the press to draw attention to landowners’ attacks on his community, traveling from the southern highlands to Lima to publicize his cause. On Quispe, see Marisol de la Cadena, Indigenous Mestizos: The Politics of Race and Culture in Cuzco, Peru, 1919–1991 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2000): 306–10. See also a rare untitled interview with an unnamed Indigenous activist attesting to the obstacles facing Andean peasants in the courts, in El Comercio (Cuzco),March 27, 1922, 2.

In Chambi’s time, photography was perceived as a privileged mode of objective representation. During the nineteenth century, photographs gained the status of evidence through their role in the development of criminology, forensics, and surveillance.7John Tagg, The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993). Campesinos Testifying shirks this social function. Even before the loss of context rendered the image ambiguous, it had failed to serve as a testimonial, revealing the camera to be an unreliable witness. According to historian Alfredo Flores Galindo, when called to court to testify against their interests, Andean peasants occasionally refused to speak. 8Alberto Flores Galindo, In Search of an Inca: Identity and Utopia in the Andes, ed. and trans. Carlos Aguirre, Charles F. Walker and Willie Hiatt, (1986; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 173. As a mute record, perhaps Chambi’s photograph mirrors this strategy, its silence intentional rather than circumstantial.

The author wishes to thank Beverly Adams for facilitating this publication, as well as Horacio Ramos, Hannah Rose Blakeley and Fedor Karmanov for thinking through it with her.

Campesinos Testifying was on view at the Museum in a collection gallery related to Indigenism, a movement of considerable cultural and political influence across Latin America in the early twentieth century that sought to redress the oppression of Indigenous peoples.

- 1Projects: Martín Chambi and Edward Ranney was on view at MoMA from March 23 to May 3, 1979.

- 2“La literatura indigenista no puede darnos una versión rigurosamente verista del indio. Tiene que idealizarlo y estilizarlo. Tampoco puede darnos su propia ánima. Es todavía una literatura de mestizos. Por eso se llama indigenista y no indígena.” José Carlos Maríategui, Siete Ensayos de Interpretación de la Realidad Peruana (1928; Barcelona: Linkgua, 2009), 288.

- 3For a thorough analysis of Chambi’s relationship to Indigenism, see Natalia Majluf, “Martín Chambi: Fotografía e Indigenismo,” in Chambi, ed. Natalia Majluf and Edward Ranney, exh. cat. (Lima: Museo de Arte de Lima, 2015), 274–93. Deborah Poole has shown how photographic technologies are inextricable from the construction of race in the Peruvian Andes. See Poole, Vision, Race, and Modernity: A Visual Economy of the Andean World (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997).

- 4Jorge Coronado, The Andes Imagined: Indigenismo, Society, and Modernity, (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburg Press, 2009), 160.

- 5For a history of early twentieth-century uprisings in the southern Andes, see José Deustua and José Luis Rénique, “Indigenistas y Movimientos Campesinos en el Cusco, 1918–1923,” in Intelectuales, indigenismo y descentralismo en el Perú, 1897–1931 (Cuzco: Centro de Estudios Regionales Andinos “Bartolomé de las Casas,” 1984): 69–92; and Wilfredo Kapsoli and Wilson Reátegui, El campesinado peruano: 1919–1930 (Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, 1972).

- 6Indigenous activist Miguel Quispe, for example, used the press to draw attention to landowners’ attacks on his community, traveling from the southern highlands to Lima to publicize his cause. On Quispe, see Marisol de la Cadena, Indigenous Mestizos: The Politics of Race and Culture in Cuzco, Peru, 1919–1991 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2000): 306–10. See also a rare untitled interview with an unnamed Indigenous activist attesting to the obstacles facing Andean peasants in the courts, in El Comercio (Cuzco),March 27, 1922, 2.

- 7John Tagg, The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993).

- 8Alberto Flores Galindo, In Search of an Inca: Identity and Utopia in the Andes, ed. and trans. Carlos Aguirre, Charles F. Walker and Willie Hiatt, (1986; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 173.