Scholar of performance studies Joshua Chambers-Letson considers Danh Vo’s Death Sentence, a work on paper in MoMA’s collection. From the conceptual artwork, Chambers-Letson extrapolates antinomies, in particular the coexistence of values related to life and death, continuity and termination, individuality and community.

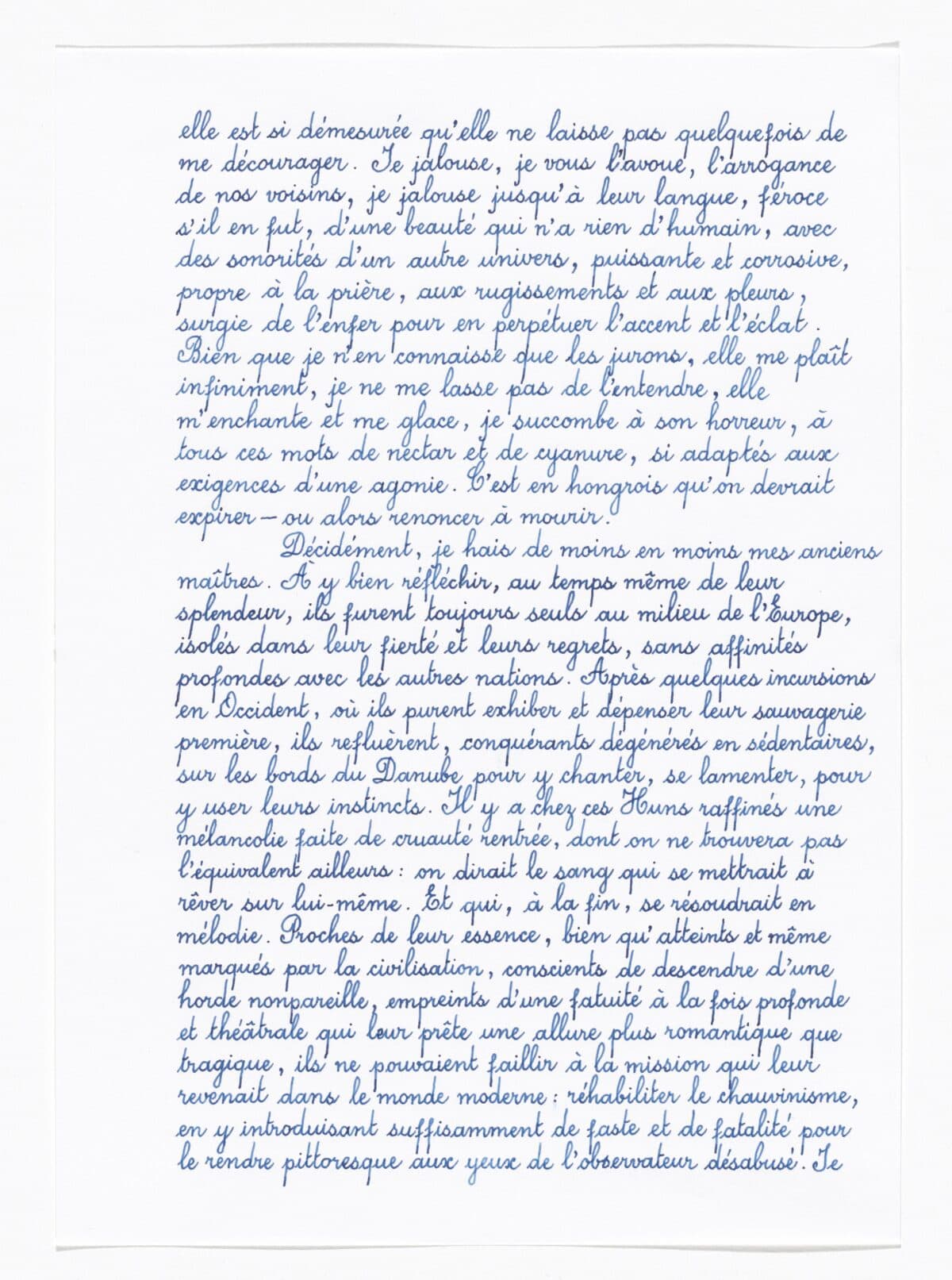

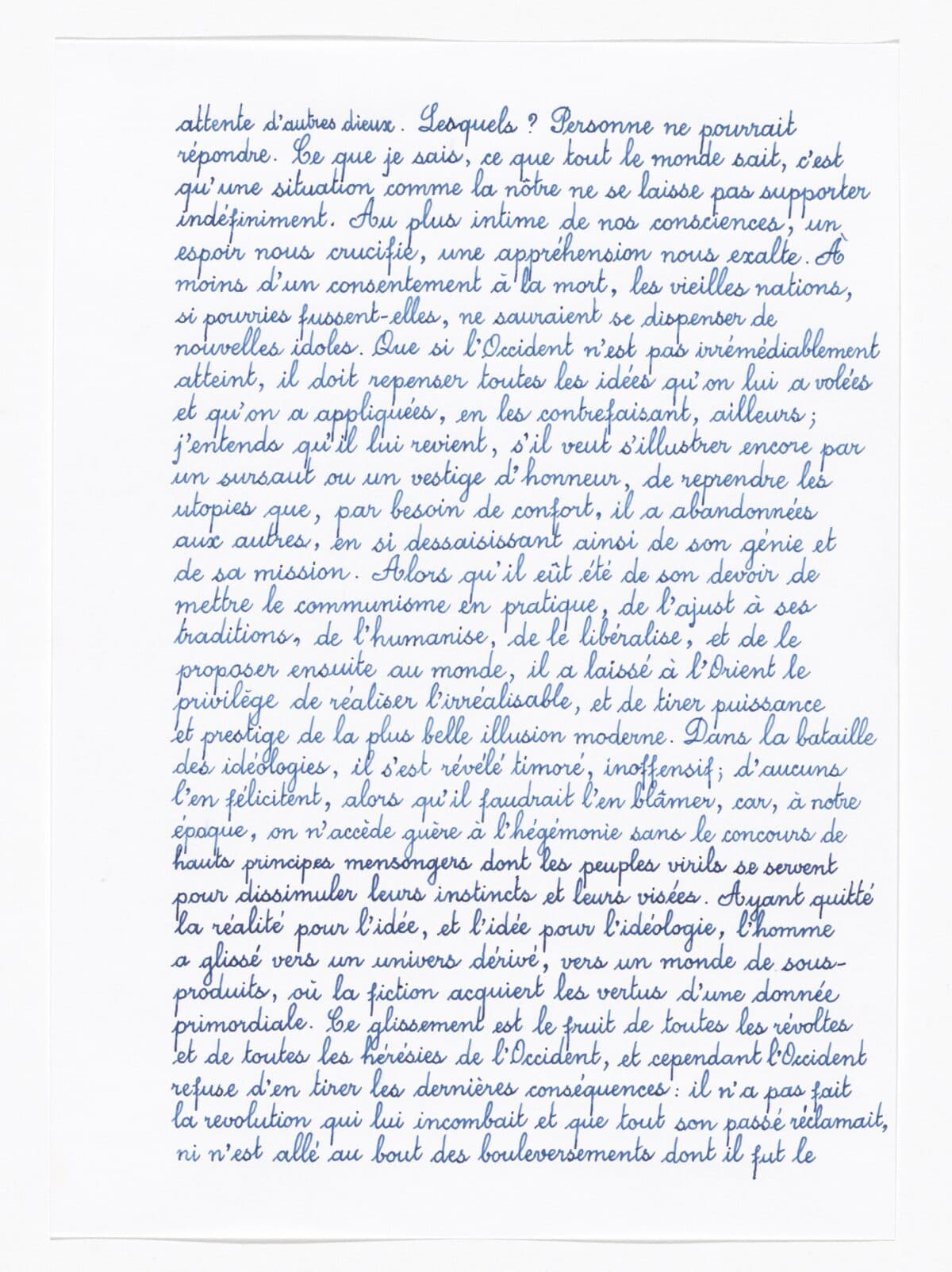

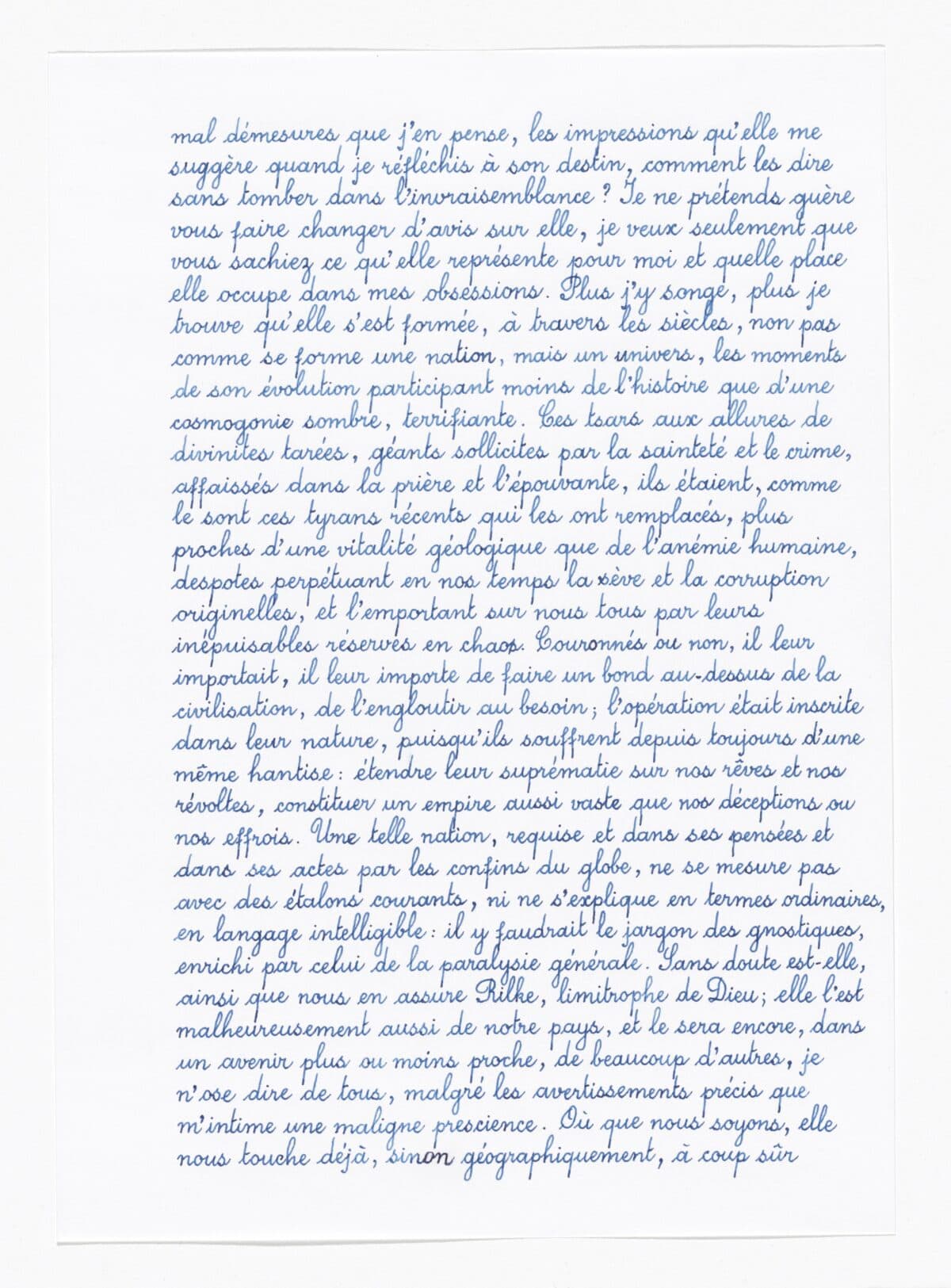

In Take My Breath Away, the Guggenheim Museum’s 2018 survey of work by artist Danh Vo (born 1975), Death Sentence (2009) was displayed in a custom shelf wrapping the inner edge of the museum’s iconic spiral ramp. Visitors encountered a sequence of sixty white sheets of standard A4-size paper adorned in blue ink calligraphy (supplied by the artist’s father, Phung Vo) in a script that is at once precise, orderly, and quickly assimilated, as it is florid, flowing, and idiosyncratic. First produced in 2009, the piece is a collaboration between the artist, his father, and his close friend and fellow artist Julie Ault (born 1957). Across the sixty pages of paper, Phung copied a sequence of five texts selected by Ault, each of which meditates, in its own quirky way, on themes of death, mourning, and representation.1They consist of a passage from a 1994 California land survey by John McPhee; an excerpt from Hungarian philosopher E. M. Cioran’s critique of Occidental culture; a passage from the diary of one of the survivors of the fated nineteenth-century Donner Party; a section of an essay by Pier Paolo Pasolini on life, death, and the cinematic capture of John Kennedy’s assassination; and J. G. Ballard’s 1968 sci-fi short story “The Dead Astronaut.” Cioran’s text is in French; the others are in English.

At the Guggenheim, the pages were placed face up on the horizontal shelf and exposed to the warm natural light flooding the atrium through the building’s oculus. Despite protective glass, the installation risked the work’s integrity since the sun pouring in through the skylight would slowly bleach the ink over the course of the exhibition’s three-month run. The willingness to court the potential destruction of an art object, appropriately titled Death Sentence, through its (re)presentation is a gesture that runs through much of Vo’s practice as he commonly curates, presents, alters, and rearranges objects that are sedimented with historical, cultural, and personal significance. Rather than treating the objects assimilated into his practice as rarefied objects of value to be preserved and protected for posterity, he approaches them as things to be worked with and used in the present.2For the 2015 installation Your mother sucks cock in Hell, for example, the artist directed his studio to saw apart a seventh-century French antiquity—a sculpture of a cherub—before displaying its new sculptural form.

My approach employs a soft Marxian analytic regarding notions of use and value.3Marx describes the usefulness or utility of a thing (it’s “use-value”) as being “only realized [verwirklicht] in use or in consumption” in volume 1 of Das Kapital (Capital), first published in Berlin in 1867. Karl Marx, Capital, vol. 1, A Critique of Political Economy, trans. Ben Fowkes, rev. ed. (1976; repr., New York: Penguin in association with New Left Review, 1990), 126. When a particular value is brought into a quantitative relation with other types of value, this quantitative metric becomes known as the object’s “exchange value.” Ibid. Part of Marx’s project in volume 1 of Capital is to trace the degree to which different registers of value (and especially “surplus value,” or the difference between the cost of making a commodity and the dearer price at which it is sold) are produced within the capitalist mode of production. There, Marx describes the process through which labor is expropriated from the laborer and congealed into commodities that are sold away at a higher price by the capitalist in control of the means of production. For Marx, capitalist value is largely centered on the production of commodities, or things that can be bought and sold in the marketplace. The commodification of art within the art market reflects this position, as the fetishistic assignment of value to a given work is often organized around the work’s physical presence as an enduring art object: something that is to be preserved, rather than used. In Vo’s practice, there is consistent refusal to preserve the commodity/art object as he purchases objects on the market before converting them back into “use values” that he consumes within his own practice. This move doesn’t necessarily subvert or resist the logic of the market, but it does invert and queer these logics as, for example, he cannibalizes these works into his broader practice, before returning them to the market to sell at a dearer rate. But in making use of them, he may alter or even, depending on one’s perspective, destroy, if not kill, them.

To make the wall-mounted installation Lot 20. Two Kennedy Administration Cabinet Room Chairs (2013), for example, Vo purchased at auction two chairs that Jackie Kennedy had given to Robert McNamara. McNamara was one of the chief architects of the Vietnam War. Kennedy gave the chairs to McNamara following the assassination of her husband John F. Kennedy, the president who oversaw the war’s commencement. A refugee of the war, Vo disassembled the chairs and displayed their leather upholstery, padding, and desiccated wooden skeletons as a deconstructed sculptural arrangement. Refusing to freeze these historically overdetermined objects in time, Vo makes use of the chairs in a fashion that rescues them from becoming nostalgic, nationalist relics, while transforming them into a still-life spectacle of vengeful, anti-imperial critique, annihilating and exposing their previous form. By acquiring these historically and ideologically charged objects only to dismantle them, the artist coolly and violently confronts the equally destructive legacy of “Camelot,” before breathing new life into these objects for and in his critical present.

As Vo makes (new) use of and (re)presents objects that are tethered to converging sites of death and mourning (the abstract scale of the death and destruction of Vietnamese life during the war alongside the intimate grieving practices of the people who designed and executed the war), he confronts the spectator with the compresence of life and death and, similarly, a mutually implicated relationship between creation and destruction. These pairs do not form oppositional binaries, but instead are resolved into a state of constant, co-constitutive relation. Life with death, creation with destruction.

Exposing Death Sentence to the sun might have destroyed the work, but it was not the Guggenheim’s to destroy. The piece was on loan from The Museum of Modern Art, which, in 2010, acquired Death Sentence along with two of Vo’s other works. For that acquisition, Vo’s gallery supplied MoMA with an invoice doubling as the artist’s certificate of authenticity, a copy of Phung’s text, an appendix with a bibliography of the five texts comprising the work, and instructions for manufacturing the custom wood, glass, and metal cabinet to be used for its display.4Photocopy of Danh Vo and The Museum of Modern Art, “Non-Exclusive License [for Death Sentence and Last Letter of saint [sic.] Theophane Venard to his father before he was decapitated copied by Phung Vo] and Object Questionnaire [sic.],” October 1, 2010.

Through the certificate of authenticity, Vo cites the conceptual practice of one of his major influences, Félix González-Torres (1957–1996), who often supplied collectors with certificates of authenticity and instructions for assembling his work, thus forgoing the delivery of an enduring art object. The work’s life, in such pieces, need not exist as ossified commodity. It may exist instead, when it is staged or performed in a given time and place and in relation to a specific public.5This notion resonates with the approach of progenitors of conceptual art including Yoko Ono (born 1933) as well as Joseph Kosuth (born 1945), with whom Félix González-Torres was in direct conversation. Felix Gonzalez-Torres and Joseph Kosuth, “A Conversation,” in Felix Gonzalez-Torres, ed. Julie Ault (New York and Göttingen: Steidl, 2006), 348-360. I have elaborated on this relationship between time, performance, labor, and the art object as commodity in Vo’s and González-Torres’s work extensively in Joshua Chambers-Letson, After the Party: A Manifesto for Queer of Color Life (New York: New York University Press, 2018): 1–36, 81–162. As a conceptual work, however, Death Sentence is distinguished by the presence of an enduring object as its central component: Phung’s text. Unwilling to risk the destruction of MoMA’s property via the artist’s ongoing use of the work at the Guggenheim, it was decided that for this particular installation, Phung would produce a new copy of the text, which would be subject to slow death by ultraviolet bath. MoMA would retain its “original.”6I am unclear as to the source of the solution in which Phung produced a second copy for the Guggenheim exhibition. In an email exchange, Ault underscored that the decision to display the work in the oculus was likely more about the way the work might interact with other components of the show than an innate desire to render the piece vulnerable. The decision for a second copy was centrally a question of pragmatics and conservation: Julie Ault, email message to author, January 12, 2023. My interest in underscoring the risk, vulnerability, and destruction in this manifestation of the work is less about ascribing artistic intent (that is, Vo’s desire to destroy) than to emphasize the degree to which destruction is baked into the creative process, even (especially) when destruction is not the aim. By having his father produce another copy, one fated for destruction by way of the Guggenheim’s oculus, the artist quietly questioned where the work lives or even what MoMA has purchased. Does the museum own the concept for the piece, it’s schematics, Phung’s first sixty-page copy of the manuscript, the right to materialize the work, or some combination of these and other elements? Further, the solution worked out for the Guggenheim exhibition raised the question of whether the work could ever truly be possessed or destroyed. I am less interested in resolving these questions than I am in the way Vo’s practice consistently raises them. As he does so, he places pressure on a conception of “value” that is grounded in the preservation of the art object as commodity, and suggests instead a notion of art as a ceaselessly unfolding process/practice of mutually implied creation and destruction. One that appropriates objects and artworks to use and consume them in the making of new work. The impulse is not merely, or not always, destructive.7Recognizing the degree of value conferred by his own signature, for example, Vo’s purchased objects held in the private collection of the late artist Martin Wong (1946–1999) and his mother, Florence Wong Fie, with the intention of transforming them into a work (I M U U R 2) so that they could be preserved together (as they have been in the collection of the Walker Art Center). Rather, it may be instructive insofar as it teaches a powerful set of lessons about living with destruction, if not the universal death sentence that accompanies all forms of living.

It is significant that Phung produced Death Sentence with the same ink and calligraphic style that he used for another ongoing collaboration with his son, 2.2.1861 (2009).8MoMA purchased an edition of 2.2.1861 at the same time as it acquired Death Sentence. For this latter work, which is also on paper, Phung reproduced a letter sent from French missionary Jean-Théophane Vénard to his father on the event of his beheading, having been condemned to death by the Vietnamese crown for illegal proselytization. In it, Vénard writes that “all [involved] regret that the law of the kingdom condemns me to the death sentence.”9Danh Vo, 2 Février, 1861 / Phung Võ (Bregenz: Kunsthause Bregenz, 2013), 234. The French passage reads, “regrettent que la loi du royaume me condamne a la mort,” and the English translation I have used appears here as well. It is dated January 20, 1861. The artwork’s title refers to the fact that the letter was received by the father some days later, after his son’s death, on February 2, 1861. The piece is editioned, but the edition will only be defined by the conclusion of Phung’s own life. As Vo writes, “My father will write this letter repeatedly until he dies,” suggesting that the work itself is a kind of “death sentence.”10Vo, 2 Février, 1861 / Phung Vo, 234. The number of editions will be determined by the number of times the piece is purchased until Phung dies. MoMA acquired Death Sentence for its collection together with an edition of 2.2.1861. When displayed in relation to Death Sentence, as it did in the Guggenheim’s rotunda in Take My Breath Away, the two works offer a profound meditation on the compresence of a multitude of unfolding presents with the finitude of death: that is, not life versus death, but the mutual implication of life and death (as well as creation and destruction) with each other.

The origins of Death Sentence are based in Vo’s friendship with Ault, one born from the grounds of queer of color loss. González-Torres died in 1996 at age thirty-eight amid the first waves of the AIDS crisis. He has been a major influence on Vo’s practice, and the two share a set of formal and autobiographical similarities. Both are artists who deploy sculptural, conceptual, and performance dynamics in their practices, just as both are queer men and refugees of the Cold War (Cuba and Vietnam, respectively) who incorporate autobiographical matter into their work. But by the time Vo encountered the work of this queer ancestor, or Cold War cousin, González-Torres was already dead.

Ault was one of González-Torres’s dearest friends and collaborators. They worked closely together and, in 1987, Ault helped recruit him to join the conceptual art collective Group Material. In the early 2000s, Ault was briefly in residence in Denmark, where Vo’s family settled after escaping Vietnam by boat when he was a child. He sought her out with questions about González-Torres’s practice and process. According to Vo , she was interested in what the “next generation” of artists would do with González-Torres’s legacy. She was immersed in editing her 2006 compendium Felix González-Torres11Ault, Félix González-Torres. and the two began a dialogue regarding González-Torres. This dialogue led to a deep and ongoing friendship.12Danh Vo, in conversation with the author at the artist’s home in Güldenhof, Germany, August 20, 2022.

As he was preparing for his landmark 2009 exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel, Where the Lions Are, Vo invited Ault to write a text for the exhibition catalogue. She was unsure at first, but they agreed to meet at a film festival in Argentina where they continued the exchange. Of the trip he remembers only the consuming nature of their conversations at the hotel and the films. Ault would later reflect that “the period was exuberant and exhausting; we thrived on and suffered from utter mental saturation.”13Julie Ault, “Appendix: 1–47,” in Where the Lions Are, ed. Adam Szymczyk (Basel: Kunsthalle Basel, 2009), 1-45. From the exchange, Ault curated the five texts to be reproduced at the catalogue’s conclusion in lieu of the traditional catalogue essay, titling her contribution “Death Sentence.” Doing so, she sought to avoid the exegetical form that is the norm for the catalogue essay: “It didn’t ring true for me to interpret or explain Danh’s work. It didn’t make sense to have something like a unified narrative.”14Julie Ault and Katherine Brinson, “Death Sentence by Danh Vo,” Guggenheim Museum website, January 31, 2018, https://www.guggenheim.org/audio/track/death-sentence-by-danh-vo. Rather, and in Vo’s own words, he “wanted a text that I could use for the future . . . something to learn from. That you can carry with you. I think that’s also what I mean when I think of artwork. No? It just sits there and you keep thinking about it.”15Vo, in conversation with the author, August 20, 2022. Sharing the desire for a text that could be worked with and used over time, rather than explaining and fixing Vo’s work in time, Ault chose texts that “bore a kind of analogic . . . significance to Danh’s way of thinking and working . . . because of the way that they would, together, as a whole, configure, not diagram, but begin to configure, or suggest, a kind of unfolding of the cosmology of Danh’s practice.”16Ault and Brinson, “Death Sentence by Danh Vo.” Her hope that Vo would continue to work with the texts bore immediate fruits as he absorbed them into a new piece, also titled Death Sentence, which was first displayed at Art Basel in Miami Beach in 2009 before being purchased by MoMA in 2010.

Reading the five texts in sequence, one finds a wide range of resonances with Vo’s practice. In a lushly poetic fragment from a California land survey, for example, one catches descriptive language that seems presciently relevant to Vo’s conceptual approach. The author, John McPhee, lyrically narrates the earth’s story through the analogy of furniture housed in an attic, all in different styles and from different eras. Resonating with Vo’s practice of curating and (re)presenting objects amid shifting contexts and points of reference, McPhee writes that one tells such objects’ stories by moving “backward through shifting space to differing points in time,” before consoling the reader by telling them that “you can’t see the story whole. You cannot tell when each of these items has come, any more than its maker could have known where it would go.”17Citations for Death Sentence are drawn from, and use pagination, from Ault, “Death Sentence,” in Where The Lions Are, ed. Szymczyk. Ault, “Death Sentence,” 2. This emphasis on subjective experience and contextual meaning making not only points to Vo’s methods, but also resonates with tactics deployed by Ault and Gonzalez-Torres (as evidenced in Group Material’s seminal AIDS Timeline of 1989).18In an introduction to Ault’s anthology of writings, critic Lucy Lippard describes Ault’s emphasis on context and meaning making as a decentralized process, or practice, rather than an end point. This emphasis on decentralization is reflected in hers and González-Torres’s practices, as well as in the formal approach to compiling the text for “Death Sentence.” Citing Ault, Lippard writes, “Ault sees decentralization as an open-ended strategy privileging no single point of view. . . The trick to working within such a decentralized field, she [Ault] writes, ‘is to find just enough mechanisms so that people can make relevant connections. This is precisely where art can be useful.” Lucy P. Lippard, “A State of Unending Inquiry,” in In Part: Writings by Julie Ault, ed. Nicolas Linnert (Brooklyn: Dancing Foxes Press in association with Galerie Buchholz, 2017), viii.

A fragment from an essay by Pier Paolo Pasolini, in turn, dissects the cinematic footage of Kennedy’s assassination. Reading the footage, Pasolini describes the way a sequence of cinematic shots form a multitude of unfolding, subjective presents. Through the effects of montage, he writes, “We obtain a multiplication of ‘presents,’ as if an action, instead of unfolding only once before our eyes, unfolded more times.”19Ault, “Death Sentence,” 28, original emphasis. The act of cinematic editing (of editing the multiplication of presents into a single, streamlined sequence) will, in turn “render the present past”just as death provides a completed form for a life that is, until that point, unfixable and multitudinous potentiality.20Ibid. The Pasolini fragment closes with the insistence that, “It is therefore absolutely necessary to die, because, so long as we live, we have no meaning, and the language of our lives . . . is untranslatable; a chaos of possibilities, a search for relations and meanings without resolution. . . Death effects an instantaneous montage of our lives.”21Ibid., 32, original emphasis. As curator Katherine Brinson has noted, Vo’s studied interest in questions of death, and his deconstruction of the binary that divides life from death, appear resonant with Pasolini’s conclusion. In her reading of Death Sentence, Brinson remarks, “In an oeuvre predicated on a belief in the incommensurable vagaries of lived experience and the flickering instability of the self, death finally arrests this ceaseless flux and is a perpetual, countering presence in the work.”22Katherine Brinson, “Little or Nothing but Life,” in Danh Vo: Take My Breath Away, exh. cat. (New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 2018), xxvii. Death functions in two competing ways here. Death is that which arrests the arc of a particular life, but it is also a kind of continuance: what Brinson describes as this “perpetual, countering presence” of death in the mix with the living.23Ibid.

By refusing to provide a “unified narrative” of Vo’s practice by way of an exegetical text for Where the Lions Are, Ault sought to avoid the trap of fixing or killing the work. Instead, she provided Vo with a text (or a sequence of five texts) that could continue to live and work for him: “My hope is that ‘Death Sentence’ is something that Danh continues to read and delve into” as the text’s meanings transform and take on new life across different spaces, times, contexts, and utilizations.24Ault and Brinson, “Death Sentence by Danh Vo.” So doing, it is inevitable that old meanings might be destroyed or killed off, making way for new points of connection and entry to emerge. This is a process of living, where death and destruction are not anathemas to life, but “a perpetual, countering presence” within it. 25Brinson, “Little or Nothing but Life,” xxvii. This might suggest that when Vo exposed Death Sentence to the destructive rays of the sun, his aim was not to slay the work. In some ways, by becoming a rarefied art object acquired by MoMA and held in its collection, the piece had already been killed. By exposing it to the sun, giving it a new purpose, and giving it away to a new public, Vo sought to give it a new use, to find new life, as his work often does, in a seemingly dead and inert thing.

Vo once remarked to me, “The art world thinks I destroy things.”26Danh Vo, in conversation with the author at the artist’s home in Berlin, Germany, on December 8, 2022. He didn’t finish the thought, but I inferred that he understood this particular “unified narrative” of his practice as incomplete, if not inaccurate. Death and destruction are not, within his work, finite or conclusory. They are not the period delimiting the end of a (death) sentence. They are, instead, a part of the ceaselessly unfolding project of living. Rather, and in keeping with something Sigmund Freud once argued, death here does not run counter to life, so much as it is the realization of life’s aim.27This conclusion appears in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920), where Freud notes, “If we are to take it as a truth that knows no exception that everything living dies for internal reasons—becomes inorganic once again—then we shall be compelled to say that ‘the aim of all life is death’ and, looking backwards, that ‘inanimate things existed before living ones.” Sigmund Freud, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, ed. James Strachey, trans. James Strachey, rev. ed. (1961; repr., New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1989), 45–46. Emphasis original. That is, living is, always and at the same time, a process of dying, and all living matter ultimately comes from, and returns to, the pregnant nothingness that we sometimes call “death.” To put a work of art to use in the present, and presence of the living, as Vo often does, is to risk altering it and wearing it out, if not rendering it vulnerable to death and destruction. But Vo’s work is often an invitation to experience a shift in perspective. Seen otherwise, what appears to be destruction might be an invitation to come to terms with the fact that destruction and death are perpetual companions to creation, life, and the art of living on. As we are all sentenced to die, a death sentence need not necessarily be the opposite of living. As Death Sentence reminds us, it is the art of living with death that gives the act of living on meaning, substance, and stakes. A death sentence, in other words, is a precondition for More Life. It is the negotiation of this contradiction that gives life, and perhaps art, its force of power in the world.

(Boundless thanks to Danh Vo, Julie Ault, Marta Lusena, Binghao Wong, Susan Homer, and Daisy Matias (for excellent research support).

- 1They consist of a passage from a 1994 California land survey by John McPhee; an excerpt from Hungarian philosopher E. M. Cioran’s critique of Occidental culture; a passage from the diary of one of the survivors of the fated nineteenth-century Donner Party; a section of an essay by Pier Paolo Pasolini on life, death, and the cinematic capture of John Kennedy’s assassination; and J. G. Ballard’s 1968 sci-fi short story “The Dead Astronaut.” Cioran’s text is in French; the others are in English.

- 2For the 2015 installation Your mother sucks cock in Hell, for example, the artist directed his studio to saw apart a seventh-century French antiquity—a sculpture of a cherub—before displaying its new sculptural form.

- 3Marx describes the usefulness or utility of a thing (it’s “use-value”) as being “only realized [verwirklicht] in use or in consumption” in volume 1 of Das Kapital (Capital), first published in Berlin in 1867. Karl Marx, Capital, vol. 1, A Critique of Political Economy, trans. Ben Fowkes, rev. ed. (1976; repr., New York: Penguin in association with New Left Review, 1990), 126. When a particular value is brought into a quantitative relation with other types of value, this quantitative metric becomes known as the object’s “exchange value.” Ibid. Part of Marx’s project in volume 1 of Capital is to trace the degree to which different registers of value (and especially “surplus value,” or the difference between the cost of making a commodity and the dearer price at which it is sold) are produced within the capitalist mode of production. There, Marx describes the process through which labor is expropriated from the laborer and congealed into commodities that are sold away at a higher price by the capitalist in control of the means of production.

- 4Photocopy of Danh Vo and The Museum of Modern Art, “Non-Exclusive License [for Death Sentence and Last Letter of saint [sic.] Theophane Venard to his father before he was decapitated copied by Phung Vo] and Object Questionnaire [sic.],” October 1, 2010.

- 5This notion resonates with the approach of progenitors of conceptual art including Yoko Ono (born 1933) as well as Joseph Kosuth (born 1945), with whom Félix González-Torres was in direct conversation. Felix Gonzalez-Torres and Joseph Kosuth, “A Conversation,” in Felix Gonzalez-Torres, ed. Julie Ault (New York and Göttingen: Steidl, 2006), 348-360. I have elaborated on this relationship between time, performance, labor, and the art object as commodity in Vo’s and González-Torres’s work extensively in Joshua Chambers-Letson, After the Party: A Manifesto for Queer of Color Life (New York: New York University Press, 2018): 1–36, 81–162.

- 6I am unclear as to the source of the solution in which Phung produced a second copy for the Guggenheim exhibition. In an email exchange, Ault underscored that the decision to display the work in the oculus was likely more about the way the work might interact with other components of the show than an innate desire to render the piece vulnerable. The decision for a second copy was centrally a question of pragmatics and conservation: Julie Ault, email message to author, January 12, 2023. My interest in underscoring the risk, vulnerability, and destruction in this manifestation of the work is less about ascribing artistic intent (that is, Vo’s desire to destroy) than to emphasize the degree to which destruction is baked into the creative process, even (especially) when destruction is not the aim.

- 7Recognizing the degree of value conferred by his own signature, for example, Vo’s purchased objects held in the private collection of the late artist Martin Wong (1946–1999) and his mother, Florence Wong Fie, with the intention of transforming them into a work (I M U U R 2) so that they could be preserved together (as they have been in the collection of the Walker Art Center).

- 8MoMA purchased an edition of 2.2.1861 at the same time as it acquired Death Sentence.

- 9Danh Vo, 2 Février, 1861 / Phung Võ (Bregenz: Kunsthause Bregenz, 2013), 234. The French passage reads, “regrettent que la loi du royaume me condamne a la mort,” and the English translation I have used appears here as well.

- 10Vo, 2 Février, 1861 / Phung Vo, 234.

- 11Ault, Félix González-Torres.

- 12Danh Vo, in conversation with the author at the artist’s home in Güldenhof, Germany, August 20, 2022.

- 13Julie Ault, “Appendix: 1–47,” in Where the Lions Are, ed. Adam Szymczyk (Basel: Kunsthalle Basel, 2009), 1-45.

- 14Julie Ault and Katherine Brinson, “Death Sentence by Danh Vo,” Guggenheim Museum website, January 31, 2018, https://www.guggenheim.org/audio/track/death-sentence-by-danh-vo.

- 15Vo, in conversation with the author, August 20, 2022.

- 16Ault and Brinson, “Death Sentence by Danh Vo.”

- 17Citations for Death Sentence are drawn from, and use pagination, from Ault, “Death Sentence,” in Where The Lions Are, ed. Szymczyk. Ault, “Death Sentence,” 2.

- 18In an introduction to Ault’s anthology of writings, critic Lucy Lippard describes Ault’s emphasis on context and meaning making as a decentralized process, or practice, rather than an end point. This emphasis on decentralization is reflected in hers and González-Torres’s practices, as well as in the formal approach to compiling the text for “Death Sentence.” Citing Ault, Lippard writes, “Ault sees decentralization as an open-ended strategy privileging no single point of view. . . The trick to working within such a decentralized field, she [Ault] writes, ‘is to find just enough mechanisms so that people can make relevant connections. This is precisely where art can be useful.” Lucy P. Lippard, “A State of Unending Inquiry,” in In Part: Writings by Julie Ault, ed. Nicolas Linnert (Brooklyn: Dancing Foxes Press in association with Galerie Buchholz, 2017), viii.

- 19Ault, “Death Sentence,” 28, original emphasis.

- 20Ibid.

- 21Ibid., 32, original emphasis.

- 22Katherine Brinson, “Little or Nothing but Life,” in Danh Vo: Take My Breath Away, exh. cat. (New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 2018), xxvii.

- 23Ibid.

- 24Ault and Brinson, “Death Sentence by Danh Vo.”

- 25Brinson, “Little or Nothing but Life,” xxvii.

- 26Danh Vo, in conversation with the author at the artist’s home in Berlin, Germany, on December 8, 2022.

- 27This conclusion appears in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920), where Freud notes, “If we are to take it as a truth that knows no exception that everything living dies for internal reasons—becomes inorganic once again—then we shall be compelled to say that ‘the aim of all life is death’ and, looking backwards, that ‘inanimate things existed before living ones.” Sigmund Freud, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, ed. James Strachey, trans. James Strachey, rev. ed. (1961; repr., New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1989), 45–46. Emphasis original.