The author applies what they call “a Buddhist reading” to Rirkrit Tiravanija’s Untitled (rucksack installation), 1993, an artwork in MoMA’s collection, analyzing it alongside recent developments in contemporary Thai art and politics.

You are packing what you need for a ten-day journey to a foreign country into a carry-on backpack. What do you carry with you?

Rirkrit Tiravanija’s answer was several ziplock bags of curry paste, spices, and dried ingredients for a Thai rice dish, plastic utensils, a can opener, coconut milk, plastic bottles of oil and sauce, tea, an Open Country Campware five-piece mess kit, a camping stove, and a folded paper map made of photocopies (fig. 1). These all fit into a roughly thirty-liter Eastern Mountain Sports black canvas backpack. Untitled (rucksack installation) (1993) was created as a study for Untitled (From Barajas . . . to Reina Sofia) (1994).1Jan Pfeiffer, Studio Tiravanija, “Rirkrit Article for MoMA,” October 7, 2022. The later work—Tiravanija’s contribution to a group show at the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid—took from the 1993 study the portability of dry ingredients in order to prepare meals on the road. Over ten days, Tiravanija traveled from the airport to the museum on a bike equipped with cooking supplies, stopping to cook food for people along the way, and supplementing the dry ingredients in his rucksack with fresh ones purchased locally.2Ibid., October 11, 2022. The six editions of Untitled (rucksack installation), each carrying a slightly different set of alimentary items, were never actually used to prepare meals.3Ibid., October 7, 2022. This peeved Tiravanija, who noted that the rucksack “has to have a history for it to become something.”4Richard Flood and Rochelle Steiner, “En route,” Parkett 44 (1995): 115. In 1995, he encouraged the director and chief curator of the Walker Art Center to take the museum’s purchased edition out of storage, to “put it on their backs and walk out into the garden and make a meal with it.”5Ibid.

The work began with a suggestion from gallerist Helga Maria Klosterfelde to create an edition of works related to Tiravanija’s itinerant lifestyle, “always on the road, always in planes, hospitality/service with Thai food.”6Jan Pfeiffer, Studio Tiravanija, “Rirkrit Article for MoMA,” September 26, 2022. The concept of being Thai abroad was familiar to Tiravanija. In a 2004 interview, he said, “All work that I have ever made is about the position I am in the Western world, which I was trying to understand.”7Delia Bajo and Brainard Carey, “RIRKRIT TIRAVANIJA with Delia Bajo and Brainard Carey,” Brooklyn Rail, February 1, 2004, https://brooklynrail.org/2004/02/art/rirkrit-tiravanija. Having grown up the son of a diplomat, Tiravanija has said that when he moved from Bangkok to Ontario at age nineteen, “I knew nothing about my own culture.”8Ibid. His subsequent work drove toward “getting [him]self back” and untangling his “subconsciously colonized” upbringing and American Catholic education. Through his practice, Tiravanija acquires and unpacks cultural baggage using some of the most widely known, even clichéd, foreign afterimages of Thai culture: food and Buddhism.9Ibid. This article takes up the gift of food in Untitled (rucksack installation) to reframe Tiravanija’s artistic practice through the lens of Buddhism.

Emptying a Rucksack

Feel the weight of your backpack, filled with necessary items for your travels. Now, take everything out and give it away. Your backpack still has something in it: emptiness.

Tiravanija’s itinerant lifestyle and meandering path to empty his rucksack in Untitled (From Barajas . . . to Reina Sofia) mirrors that of wandering Buddhist monks. The Thai word บรรพชิต (monk/clergyman) derives from pabbajati in the scriptural language of Theravada Buddhism, meaning “to leave home and wander about as mendicant or to give up the world.”10Yoneo Ishii, “Church and State in Thailand,” Far Eastern Survey 8, no. 10 (May 1939): 864, https://doi.org/10.2307/2642085. The constant movement of monks frees them from earthly attachment and creates the opportunity for laypeople to gain merit through giving.11Richard B. Mather, “The Bonze’s Begging Bowl: Eating Practices in Buddhist Monasteries of Medieval India and China,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 101, no. 4 (October –December 1981): 418, https://doi.org/10.2307/601214. Instead of cooking tools, wandering monks carry on their person eight necessary items (บริขาร), including a robe, razor, sewing needle, and alms bowl (บาตร). Instead of begging for rice, Tiravanija cooks it for others.

Tiravanija’s generosity has been analyzed extensively with respect to European philosophies of the gift and alternative economies of reciprocity.12See Claire Bishop, “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics,” October 110 (Autumn 2004): 67; Janet Kraynak, “Rirkrit Tiravanija’s Liability,” Documents, no. 13 (Fall 1998): 28, https://doi.org/10.1162/0162287042379810; and Miwon Kwon, “Exchange Rate: On Obligation and Reciprocity in Some Art of the 1960s and After,” in Work Ethic, ed. Helen Molesworth et al., exh. cat. (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press in association with the Baltimore Museum of Art, 2003), 87. In the 1990s, when Tiravanija first began his now-iconic performances with food, critics were quick to contrast Tiravanija’s gifts of food with the artwork-as-commodity, pointing to his creation of a “familial atmosphere” as a haven from the rapidly commercializing art world.13Kraynak, “Rirkrit Tiravanija’s Liability,” 28. Tempering such notions of conviviality, Janet Kraynak has taken up Marcel Mauss’s theory of the gift as a pre-evolution of economic commodities, arguing that participants in Tiravanija’s work are swept into a sort of market with a predetermined “system of reciprocal obligations.”14Ibid., 33. Miwon Kwon, building on Kraynak, assumes Mauss’s view that “there is no such thing as a free gift or entirely disinterested, uncalculated giving.”15Kwon, “Exchange Rate,” 87. According to a 2019 interview, however, Tiravanija saw the relational conditions elicited through his work existing “without judgment, precondition, and demands,” a contrast, he says, to the relational aesthetics of “Western artists.”16Chieng Wei Shieng and Clifford Loh, “The Relational Artist,” Vulture, April 3, 2019, https://vulture-magazine.com/articles/the-relational-artist. For Tiravanija, these artists’ emphasis on aesthetics distinguishes the spectator from the art, producing “objects,” as opposed to “a way of living.”17Ibid. Maussian analyses of Tiravanija’s work, rooted in a Western perspective of economy and exchange, run counter to the role of gifting in Theravada Buddhism, Tiravanija’s self-proclaimed spiritual tradition.18Bajo and Carey, “RIRKRIT TIRAVANIJA with Delia Bajo and Brainard Carey.”

One of the primary practices of Buddhism is dana (generous giving, religious gift). According to eminent religious scholar Diana Eck, dana’s “moral energy runs against the grain of Mauss’s theory.”19Diana L. Eck, “The Religious Gift: Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain Perspectives on Dana,” in “Giving: Caring for the Needs of Strangers,” special issue, Social Research 80, no. 2 (Summer 2013): 361. Unlike the gifting practices in most modern societies, dana—gifts from laypeople to worthy receivers (usually renouncers of worldly things)—is definitionally nonreciprocal. It is in this nonreciprocity that dana’s spiritual power lies.20Ibid. In Thailand, the most common form of dana is giving rice to monks, and if the gift is freely given (without desire for reciprocity), it makes merit toward one’s spiritual advancement.21Wendi L. Adamek, “The Impossibility of the Given: Representations of Merit and Emptiness in Medieval Chinese Buddhism,” History of Religions 45, no. 2 (November 2005): 135, https://doi.org/10.1086/502698. Crucially, “if even an unreciprocated gift is motivated by the desire for merit, then none will result.”22James Laidlaw, “A Free Gift Makes No Friends,” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 6, no. 4 (December 2000): 624. As the public gains merit through dana, the monks—dispossessed of material goods—are (at least symbolically) dependent on the gifts begged each morning for survival.23Ishii, “Church and State in Thailand,” 865. Any notion of debt between renouncers and donors is neutralized by “the universal and impersonal currency—merit,” which is karmically returned to givers and which renouncers elicit through mass ritual.24Adamek, “The Impossibility of the Given,” 139, 141. Buddhist gifts, then, operate via “individual donors and no individual recipients.”25Ibid., 141. Monks and laypeople are systemically intertwined in a bilateral, existentially dependent relationship of givers and receivers of food, merit, and ultimately, spiritual liberation. Seen in this light, Tiravanija’s gifts of rice may not be setting up economies of reciprocity under capitalism but rather a way to make merit through dana.

One might label the bilateral giving between laypeople and renouncers as “reciprocity,” but it transcends the capitalist notion of economic exchange and even “symbolic capital”26Kraynak, “Rirkrit Tiravanija’s Liability,” 35. in that its process, substance, and ultimate goal is not the circulation of value, but rather emptiness. Scholar of Buddhism Wendi Adamek asserts that “for Buddhists, merit/gift is sustained by emptiness.”27Adamek, “The Impossibility of the Given,” 137. This is because for Buddhists, emptiness is a state of realizing the inherent mutuality of all things, whereas, for Jacques Derrida (building on Mauss), interconnectedness comes through exchange.28Ibid., 138. The goal of emptiness is grounded in the Buddha’s teaching that suffering is born from “our propensity for craving and grasping, our attempt to hold on tight to the world.”29Eck, “The Religious Gift,” 364. If givers hold ambitions of reciprocity, or recipients do not fulfill the requirement of “being unwilling” to receive the gift, they risk suffering somatic and karmic harm for their greed.30Laidlaw, “A Free Gift Makes No Friends,” 630. One can imagine Tiravanija’s rucksack getting emptier over the ten-day journey, the artist’s physical and spiritual load lightened through gifting to others.

Applying Mauss to Tiravanija’s work leaves little room for the use value of a truly free gift, which lies in the negative space or emptiness it leaves behind. In contrast to the collection and preservation logic of museums like the Walker that house—or hoard—Tiravanija’s works, Buddhist renouncers must give up material possessions. Additionally, renouncers train to have an empty mind (จิตว่าง) that is open to receive teachings: an immeasurable gift.31Ibid., 625. This wisdom likens the value of an empty mind to that of an empty bowl, which lies in its capacity.32B. Boisen, comp., “Eleven,” in Lao Tzu’s Tao-Teh-Ching: A Parallel Translation Collection (Boston: GNOMAD Publishing, 1996), https://www.bu.edu/religion/files/pdf/Tao_Teh_Ching_Translations.pdf. Tiravanija attributes his own empty mind (and poor memory) to “the speed of travel,” and his Buddhist philosophy “of living now, not in the future or past.”33Bajo and Carey, “RIRKRIT TIRAVANIJA with Delia Bajo and Brainard Carey.” Tiravanija’s cultivation of an empty mind gives rise to site-specific works that adapt to foreign spaces and unfold into the undetermined present. It also supports his practice of gift-giving. For Derrida, self-awareness of one’s giving (and the resultant self-congratulation or desire for reward) destroys a gift, and so “absolute forgetting” can preserve it.34Adamek, “The Impossibility of the Given,” 177. In addition to the exercise of forgetting, Tiravanija’s practice exercises another requirement of dana: detachment from the fruits of one’s actions.35Eck, “The Religious Gift,” 370. Curator Laura Hoptman described Tiravanija’s release of ownership over the outcome of a 1997 work at MoMA in terms of “reticence approaching self-abnegation,” in which he left the substance of the artwork “up to chance.”36Laura Hoptman, “Projects 58: Rirkrit Tiravanija,” exh. brochure (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1997), https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_242_300015283.pdf. This approximates the Buddhist principle of non-determination, which Tiravanija also reflects in his contentedness to “land wherever” in his travels.37Renate Dohmen, “Towards a Cosmopolitan Criticality: Relational Aesthetics, Rirkrit Tiravanija and Transnational Encounters with Pad Thai,” in “Cosmopolitanism as Critical and Creative Practice,” special issue, Open Arts Journal, no. 1 (Summer 2013): 41, https://doi.org/10.5456/issn.5050-3679/2013s05rd. Practicing freedom from attachment and expectation, Tiravanija’s non-controlling attitude toward his work and its outcomes positions him as a giver of dana.

Tiravanija’s work is often analyzed in terms of “community,” but Buddhists don’t give dana to strengthen community.38Bishop, “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics,” 67. Dana should be given to an “other” (Buddhist or not), contrasting with reciprocal gifts given to “one’s own people.”39Laidlaw, “A Free Gift Makes No Friends,” 630. In this way, anthropologist James Laidlaw contends that “impersonality, if it is a feature of the commodity . . . is equally a feature of the free gift,” not a point of difference, as cursory readings of Mauss may suggest.40Ibid., 632. Tiravanija’s gift is nothing personal. This Buddhist reading of gifting contrasts with Kraynak’s suggestion that “to read Tiravanija’s art as a gift is to suggest that it potentially undermines the premise of alterity.”41Kraynak, “Rirkrit Tiravanija’s Liability,” 39. Rather than undermining otherness, Tiravanija gives to those who must be definitionally “other.” Tiravanija, with the religious background to understand the perils of adopting an economic attitude toward dana, would not dare enter the process of gifting with reciprocal ambitions, even that of “building community.” Indeed, Laidlaw details how rituals of dana in Jainism, a related Indic religion, go to great lengths to avoid the creation of social bonds. This is because such bonds “preclude the transcendence of temporal causal relations” necessary to achieve the ultimate spiritual goal: enlightenment.42Laidlaw, “A Free Gift Makes No Friends,” 626. Although a Buddhist interpretation of Tiravanija’s gifts releases them from the commodity structure, I argue that this act does not form kinship, “family,” or “community,” but rather emptiness and the freedom of nonattachment.

Still, like any traveler, Tiravanija must reckon with the friction between one system of value and another. Here, the goals of emptiness and self-obliteration come up against those of consumption, advancement, and fullness, the latter of which risks reducing human interaction to economic relationships. Tiravanija’s rucksack meals in Madrid, Spain, were cooked for passersby who were likely strangers to him and Buddhism. Diana Eck points out that Thais daily encounter “saffron-robed monks with begging bowls, reminding us by their voluntary asceticism of spiritual values that cannot be gained from our busy lives of wealth and work”—values of nonattachment and dana that are abstract for Western urban audiences.43Eck, “The Religious Gift,” 364. The slippages between a gift’s intention, execution, and reception threaten to taint dana, which requires all three to align on the value of emptiness. Participants’ acceptance of the artist’s food, traditionally meant for those with nothing to give back, embodies a lesson in the “divide between greed and need.”44Kanon, “Rirkrit Tiravanija, ‘Untitled 2021 (Rich Bastards Beware),’ 2021,” Medium (blog), June 18, 2021, https://medium.com/kanon-log/rirkrit-tiravanija-untitled-2021-rich-bastards-beware-2021-e0aa0783b678. The worthiness of dana recipients determines its moral value, making the gift potentially poisonous to those who—eager to exploit its economic value—take more than they need.45Laidlaw, “A Free Gift Makes No Friends,” 630. When recipients frame free gifts through the materialistic lens of either a suspicious debt trap or an opportunity for exploitation, they miss the point: if a gift fills a need, it does not add to your load—it leaves you freer.

Using a Rucksack in Thailand Today

You are packing again, but not for travel. Add to your backpack the tools you need to build a world in which you feel at home. In other words, a world where you are free.

In a 2004 interview, Tiravanija said it is “the contemporary Thai artist’s struggle to be a Buddhist and an artist.”46Bajo and Carey, “RIRKRIT TIRAVANIJA with Delia Bajo and Brainard Carey.” In 2019, Tiravanija noted that he sees his work as a part of his “everyday spiritual practice and life,” rather than making “art” as such.47Chieng Wei Shieng and Loh, “The Relational Artist.” Untitled (rucksack installation) embodies Tiravanija’s integration of artistic and spiritual practice. It packs elements of Buddhist philosophy into Tiravanija’s travels between hubs of the global contemporary art world. Tiravanija’s rucksack, however, may take on an additional meaning in Thailand today, one that reveals the artist’s distance from his home country.

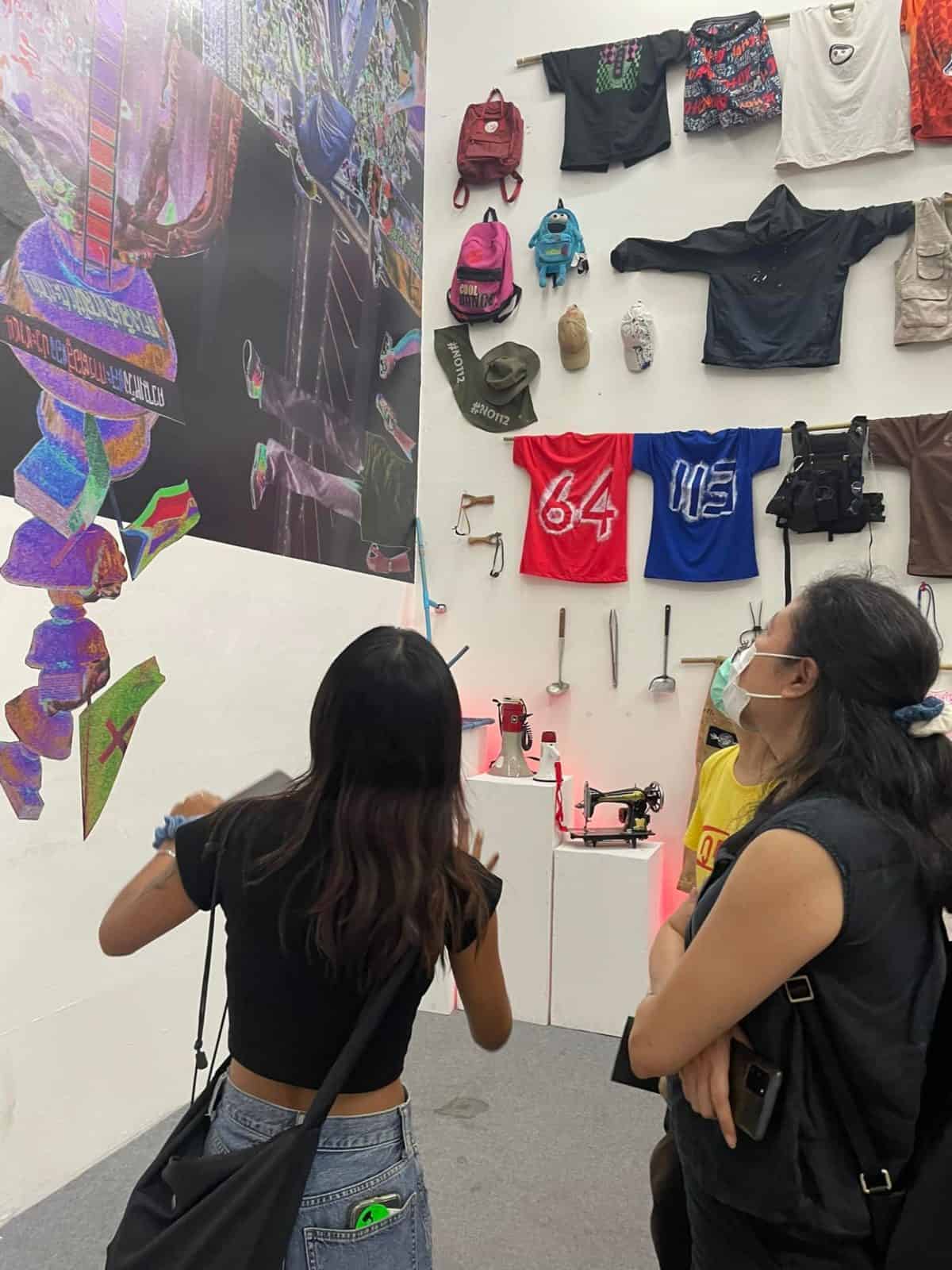

Contrast Tiravanija’s rucksack with the backpacks shown in the March 2022 exhibition Battle Wounds at Cartel Artspace in Bangkok, Thailand (fig. 2). The backpacks and accompanying protest ephemera were used by political youth group Talufa (ทะลุฟ้า,) at the protests near Bangkok’s Democracy Monument in August 2021.48Mit Jai Inn, Cartel Artspace founder, instant message to author, October 17, 2022. Like Untitled (rucksack installation), the protesters’ backpacks carried tools to make and share meals, including ladles, tongs, and spatulas. Whereas Tiravanija’s rucksack might hold the tools of a Buddhist traveler giving without desire, the backpacks in Battle Wounds equipped occupiers to hold space in the days-long “mob” protests for democratic reforms. Beginning in 2020, participants in these student-led protests cooked not for passing strangers or renouncers, but to sustain a politically grounded community that stayed put in the movement for a new national future. Along with kitchenware, their backpacks were stuffed with slingshots, gas masks, and political slogans.49Ibid. The occupiers used their backpacks to make temporary homes in public space rather than traverse it itinerantly.

By exhibiting the protest ephemera of young Thais rooted in their country, Battle Wounds offered an alternative perspective on the necessary items and methods of Thai contemporary artists and activists. Their backpacks, carrying the weight of the tools to build a future, do not leave enough empty space for dana. Understandably, the relationship between Buddhism and art is a defining question for Tiravanija—a traveler whose practice of nonattachment creates a home in the present moment. Taken in the context of 2020–22 Bangkok, this question does not, however, characterize “the contemporary Thai artist’s struggle” to shape the future of the nation. Uncannily, this contrast reflects the very phenomenon Tiravanija addresses in his art: the literal and cultural distance between his itinerant life and Thailand.

Untitled (rucksack installation) offers us insight into what it means to be a Thai traveler who has lived abroad most of their life. I have argued that the work embodies the Buddhist principles of dana, nonattachment, and non-determination, rarely gleaned in readings of Tiravanija’s artistic practice. In giving freely to Madrileños, Tiravanija opened the door to a new way of relating to the world and each other: one in which we give not to fulfill a debt, but for the lightness of being empty. Removed from their culturally specific contexts, however, these Buddhist principles are ungrounded from their spiritual and material use. Indeed, this friction and distortion in communication is the ocean in which travelers crossing philosophical traditions learn to swim. But such misunderstandings and lost meanings might attend the work’s reception even in present-day Thailand. As Battle Wounds suggests, for many young Thais, nonattachment is affordable only with the luxury of distance, or the ability to make the road, rather than a nation, your home. Ultimately, Untitled (rucksack installation) offers a Buddhist solution to Tiravanija’s impossible journey toward “getting [him]self back”: give away, and let go. Tiravanija’s work echoes the Buddhist values underpinning Thai society while untethering them from contemporary Thai geopolitics and culture. It reminds us of what a traveler cannot take with them when they leave their homeland. There are some things a rucksack cannot carry.

Acknowledgments: The editorial brilliance of Wong Binghao, Will Seaton, and Elizabeth Keto provided the directional light to grow the article into its current form. Without the confidence and inspiration of Chanon Kenji Praepipatmongkol and Thanavi Chotpradit, this article would never have been seeded. Thank you for your priceless gifts.

- 1Jan Pfeiffer, Studio Tiravanija, “Rirkrit Article for MoMA,” October 7, 2022.

- 2Ibid., October 11, 2022.

- 3Ibid., October 7, 2022.

- 4Richard Flood and Rochelle Steiner, “En route,” Parkett 44 (1995): 115.

- 5Ibid.

- 6Jan Pfeiffer, Studio Tiravanija, “Rirkrit Article for MoMA,” September 26, 2022.

- 7Delia Bajo and Brainard Carey, “RIRKRIT TIRAVANIJA with Delia Bajo and Brainard Carey,” Brooklyn Rail, February 1, 2004, https://brooklynrail.org/2004/02/art/rirkrit-tiravanija.

- 8Ibid.

- 9Ibid.

- 10Yoneo Ishii, “Church and State in Thailand,” Far Eastern Survey 8, no. 10 (May 1939): 864, https://doi.org/10.2307/2642085.

- 11Richard B. Mather, “The Bonze’s Begging Bowl: Eating Practices in Buddhist Monasteries of Medieval India and China,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 101, no. 4 (October –December 1981): 418, https://doi.org/10.2307/601214.

- 12See Claire Bishop, “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics,” October 110 (Autumn 2004): 67; Janet Kraynak, “Rirkrit Tiravanija’s Liability,” Documents, no. 13 (Fall 1998): 28, https://doi.org/10.1162/0162287042379810; and Miwon Kwon, “Exchange Rate: On Obligation and Reciprocity in Some Art of the 1960s and After,” in Work Ethic, ed. Helen Molesworth et al., exh. cat. (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press in association with the Baltimore Museum of Art, 2003), 87.

- 13Kraynak, “Rirkrit Tiravanija’s Liability,” 28.

- 14Ibid., 33.

- 15Kwon, “Exchange Rate,” 87.

- 16Chieng Wei Shieng and Clifford Loh, “The Relational Artist,” Vulture, April 3, 2019, https://vulture-magazine.com/articles/the-relational-artist.

- 17Ibid.

- 18Bajo and Carey, “RIRKRIT TIRAVANIJA with Delia Bajo and Brainard Carey.”

- 19Diana L. Eck, “The Religious Gift: Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain Perspectives on Dana,” in “Giving: Caring for the Needs of Strangers,” special issue, Social Research 80, no. 2 (Summer 2013): 361.

- 20Ibid.

- 21Wendi L. Adamek, “The Impossibility of the Given: Representations of Merit and Emptiness in Medieval Chinese Buddhism,” History of Religions 45, no. 2 (November 2005): 135, https://doi.org/10.1086/502698.

- 22James Laidlaw, “A Free Gift Makes No Friends,” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 6, no. 4 (December 2000): 624.

- 23Ishii, “Church and State in Thailand,” 865.

- 24Adamek, “The Impossibility of the Given,” 139, 141.

- 25Ibid., 141.

- 26Kraynak, “Rirkrit Tiravanija’s Liability,” 35.

- 27Adamek, “The Impossibility of the Given,” 137.

- 28Ibid., 138.

- 29Eck, “The Religious Gift,” 364.

- 30Laidlaw, “A Free Gift Makes No Friends,” 630.

- 31Ibid., 625.

- 32B. Boisen, comp., “Eleven,” in Lao Tzu’s Tao-Teh-Ching: A Parallel Translation Collection (Boston: GNOMAD Publishing, 1996), https://www.bu.edu/religion/files/pdf/Tao_Teh_Ching_Translations.pdf.

- 33Bajo and Carey, “RIRKRIT TIRAVANIJA with Delia Bajo and Brainard Carey.”

- 34Adamek, “The Impossibility of the Given,” 177.

- 35Eck, “The Religious Gift,” 370.

- 36Laura Hoptman, “Projects 58: Rirkrit Tiravanija,” exh. brochure (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1997), https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_242_300015283.pdf.

- 37Renate Dohmen, “Towards a Cosmopolitan Criticality: Relational Aesthetics, Rirkrit Tiravanija and Transnational Encounters with Pad Thai,” in “Cosmopolitanism as Critical and Creative Practice,” special issue, Open Arts Journal, no. 1 (Summer 2013): 41, https://doi.org/10.5456/issn.5050-3679/2013s05rd.

- 38Bishop, “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics,” 67.

- 39Laidlaw, “A Free Gift Makes No Friends,” 630.

- 40Ibid., 632.

- 41Kraynak, “Rirkrit Tiravanija’s Liability,” 39.

- 42Laidlaw, “A Free Gift Makes No Friends,” 626.

- 43Eck, “The Religious Gift,” 364.

- 44Kanon, “Rirkrit Tiravanija, ‘Untitled 2021 (Rich Bastards Beware),’ 2021,” Medium (blog), June 18, 2021, https://medium.com/kanon-log/rirkrit-tiravanija-untitled-2021-rich-bastards-beware-2021-e0aa0783b678.

- 45Laidlaw, “A Free Gift Makes No Friends,” 630.

- 46Bajo and Carey, “RIRKRIT TIRAVANIJA with Delia Bajo and Brainard Carey.”

- 47Chieng Wei Shieng and Loh, “The Relational Artist.”

- 48Mit Jai Inn, Cartel Artspace founder, instant message to author, October 17, 2022.

- 49Ibid.