In the mid-1980s, over the course of three years and across three continents, feminist artist Everlyn Nicodemus (born 1954, Kilimanjaro, Tanzania) gathered together women to discuss their everyday experiences. From these conversations, which took place in Skive, Denmark; Kilimanjaro, Tanzania; and Calcutta (now Kolkata), India, she produced a series of seventy-five paintings and related poems that she called “Woman in the World.”1In the case of the Tanzanian component, the conversations took place in the Kilimanjaro region, but Nicodemus painted the works in Dar es Salaam. Kristian Romare, “Woman in the World by Everlyn Nicodemus,” in Woman in the World III, exh. cat. (Calcutta: Sisirmanch, 1986), 2.Organizing such dialogues as a prelude to the act of painting was a way for the artist to reject her early training in social anthropology at Stockholm University, where she chafed at the idea that researchers could be neutral observers of communities to which they do not belong. With the permission of participants, Nicodemus taped the events. But she did not use these recordings as tools to empirically document what was shared, as one might do in academic research. Rather, through careful, solitary listening, she began to translate the joy, pain, and mundanity of women’s lives into abstracted figurations. Together these works foregrounded something latent in her earlier compositions: a desire to make the relationship between self and non-self (or “other”) a pictorial and poetic strategy based on affinity instead of an anthropological problem rooted in difference.

By her own account, Nicodemus decided to study social anthropology after being “confronted with everyday racialist attitudes for the first time when migrating to Europe.”2Everlyn Nicodemus, “African Modern Art and Black Cultural Trauma” (PhD diss., Middlesex University, 2012), 30.She had moved to Sweden in 1973 after spending her formative years in the Kilimanjaro region. Already fluent in Kichagga, Kiswahili, and English, she picked up Swedish quickly and enrolled in Stockholm University in 1978. Anthropology, she thought at the time, “seemed to offer the intellectual means to better understand human behavior,” especially the baser forms she encountered while living abroad as a Black and African woman.3Nicodemus, “African Modern Art and Black Cultural Trauma,” 30.

Once she began her coursework, however, she discovered that the discipline lacked the possibilities she imagined. Social anthropology was a relatively new offering in Swedish academia, but like all anthropological fields, it had deep roots in ethnography, which had itself emerged from the systems and structures of colonialism. About a decade before Nicodemus arrived, the university attempted to loosen these ideological ties by changing the department’s name from “General and Comparative Ethnography” to “Social Anthropology” and by moving away from curricula designed around the Museum of Ethnography collections.4See Ulf Hannerz, “Swedish Anthropology: Past and Present,” kritisk etnografi: Swedish Journal of Anthropology 1, no. 1 (2018): 55–57.Despite these changes, which might suggest a shift from a collection-based approach to studying culture and society to a people-oriented one, Nicodemus grew increasingly uncomfortable with the role of anthropologist—even as she continued her studies.

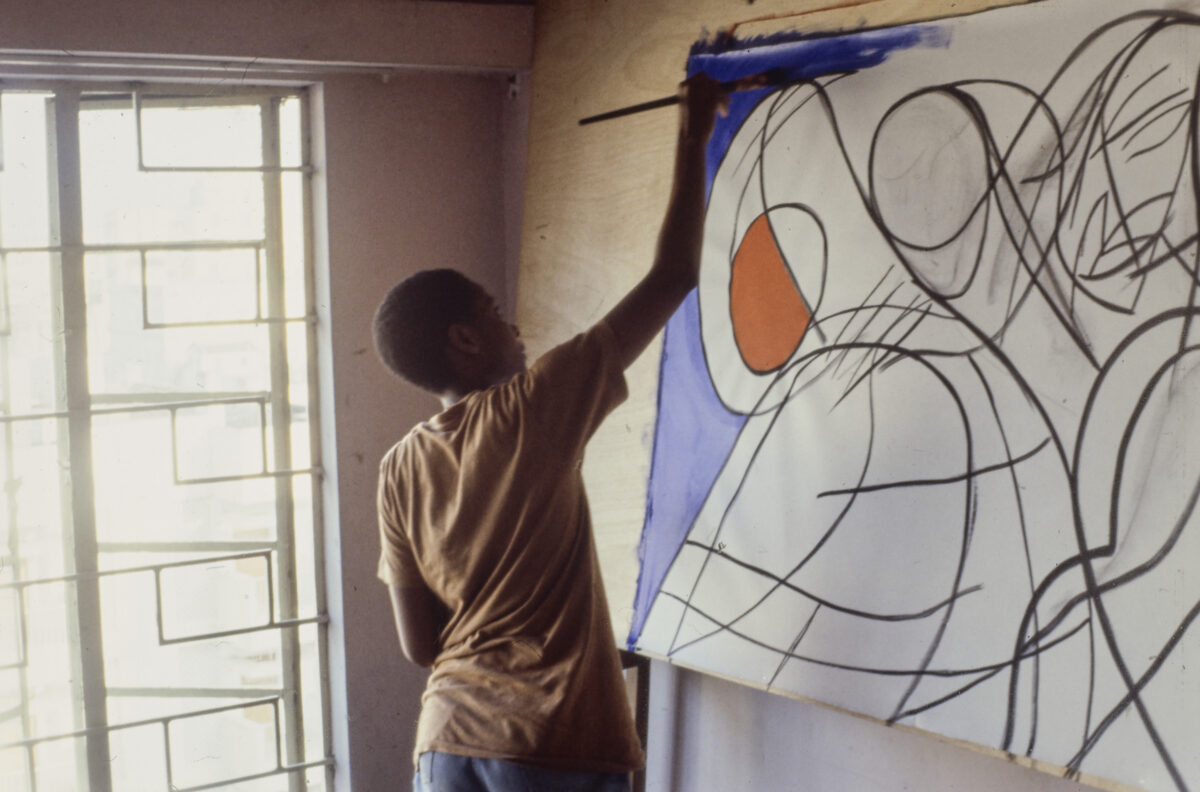

Her frustrations prompted her turn to art-making. Nicodemus returned to Tanzania in 1979 to do fieldwork while also providing Kiswahili instruction to, in her words, “Scandinavian aid workers.”5Everlyn Nicodemus and Catherine de Zegher, “The Black Color Is Joy and Pain: A Conversation between Everlyn Nicodemus and Catherine de Zegher,” in Everlyn Nicodemus: Vessels of Silence, exh. cat. (Kortrijk: Kunststichting-Kanaal-Art Foundation vzw, 1992), 6.While living in an international community of expatriates, she met some women who invited her to attend amateur drawing sessions.6Everlyn Nicodemus, email message to author, August 22, 2024.Nicodemus abandoned the sessions after a few meetings to make time for more serious artistic pursuits, resolving to have her own solo exhibition as quickly as possible.7Nicodemus and de Zegher, “The Black Color Is Joy and Pain,” 6.Nicodemus achieved her goal in 1980, when she debuted her paintings and poems in a one-woman show at the National Museum in Dar es Salaam, and preeminent Tanzanian modernist Sam Ntiro gave the opening remarks.8Everlyn Nicodemus, email message to author, February 22, 2023.

Reflecting on this period of her life in an interview with Belgian curator Catherine de Zegher in 1992, Nicodemus spoke about why anthropology troubled her so deeply and how her emerging artistic practice resolved some of the issues she identified in the discipline’s methodologies: “Anthropology demanded that I look at human beings in a way that was foreign to me. I had to disassociate myself from the humans I was to study, to deal with them as objects.”9Nicodemus and de Zegher, “The Black Color Is Joy and Pain,” 6.By contrast, the work she exhibited at the National Museum “was exactly the opposite of the objectifying approach. I exhibited myself as a subject, showing every part of myself, my problems, my hopes, my conflicts, my whole life.”10Nicodemus and de Zegher, “The Black Color Is Joy and Pain,” 8.These themes included her experiences of pregnancy, childbirth, child-rearing, and romantic love.

The artist’s comments capture aspects of critiques that had emerged among anthropologists and other scholars in the 1980s about the discipline’s operating assumptions and its origins in the enterprise of colonialism.11For a summary from the period, see George E. Marcus and Michael M. J. Fischer, Anthropology as Cultural Critique: An Experimental Moment in the Human Sciences (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986). Also helpful is the contemporaneous Edward W. Said, “Representing the Colonized: Anthropology’s Interlocutors,” Critical Inquiry 15, no. 2 (Winter 1989): 205–25.In brief, these assessments concern anthropology’s historical framework, in which cultures, and by extension peoples, are looked upon as hermetically contained entities that can be studied by supposedly outside, neutral observers and then interpreted for external audiences—often still located in the centers of Western empire. When Nicodemus says she turned herself into a “subject,” she does not mean the position of the anthropologist in relation to the ethnographic “other” as the field’s older conventions might have it; rather, she makes herself the center of the work, exploring her own vulnerabilities. An early example, After the Birth (1980) depicts a female figure curled on her side, a hand resting on—or covering—her face. A sleeping baby, the artist’s infant daughter, lies in front of her. A short poem accompanying the picture reveals the anxieties of a first-time mother both enthralled and overcome by her new responsibility.12It reads: “Here you were / laying, child / 45 cm / two-and-a-half kilos / helpless, / A whirlwind / of thoughts and emotions. / But there was / harmony in it. / This is the humanity. / Now I was a mother. / I will be a mother until my / death. / Now I am responsible. / A life.” The poem is reproduced in Everlyn Nicodemus, exh. cat.(London: Richard Saltoun Gallery, 2021), 8.

While Nicodemus has returned to her own biography throughout her career, she has increasingly framed her experiences vis-à-vis those of other women. Crucially, her paintings can be understood as situating those encounters as a series of mutual exchanges. For instance, she often describes one of her early works Two Black Candles (1983) in terms of a promise she made to acquire the bark cloth on which it is painted. Several years earlier, while pursuing her degree in anthropology, Nicodemus met an elderly woman living alone in one of the Bukoba districts near Lake Victoria.13Everlyn Nicodemus, in conversation with the author, January 13, 2023. See also Anne Wilson-Schaef, “An African Woman Gives Us ‘Woman in the World,’” Woman of Power: A Magazine of Feminism, Spirituality, and Politics, no. 7 (Summer 1987): 13–14.They spoke Kiswahili, and eventually, the woman agreed to trade Nicodemus the bark cloth for some cotton cloth—on the condition that the artist burn two black candles.14Wilson-Schaef, “An African Woman Gives Us ‘Woman in the World,’” 13–14.

Why two black candles? Nicodemus does not know exactly, except perhaps for the fact that bark cloth is used in tradition-based burials.15Everlyn Nicodemus, email message to author, August 22, 2024.In the region, the cloth is commonly associated with the Baganda people, whose kingdom in Uganda stretches to the southern border with Tanzania—an area near where this exchange took place.16For a study on bark cloth in this area, see Venny M. Nakazibwe, “Bark-Cloth of the Baganda People of Southern Uganda: A Record of Continuity and Change from the Late Eighteenth Century to the Early Twenty-first Century” (PhD diss., Middlesex University, 2005), https://repository.mdx.ac.uk/item/831w4.Historically, the fabric was produced for various purposes, including for clothing and funeral wrappings. The latter usage, Nicodemus suspects, was the reason the woman had saved it.17Nicodemus, in conversation with the author, January 13, 2023.(Incidentally, bark cloth is also the kind of cultural material that earlier generations of Western researchers would have collected for ethnographic museums, such as that in Stockholm.18As of July 31, 2024, the digital catalogue for the Världskulturmuseerna lists eight examples of bark cloth and several objects made with bark cloth from Central and Southern Africa, all of which are in the Museum of Ethnography collection. See https://www.varldskulturmuseerna.se/en/collections/search-the-collections/.)

More than anecdotal backstory, the exchange between the younger and elder women is integral to Two Black Candles. Its two female figures allegorize Nicodemus’s memory of the event—their tapered fingers dripping like wax, their bright white fingernails alight. The geometric and linear patterns of their robes flow into one another the closer they are to the ground, making the figures appear entwined. The soft texture of the bark cloth only heightens the effect. In that respect, the fabric has a dual function: It is the painting’s support, made plain by the untouched background. But it also peeks through the patterning, becoming an integral part of the represented clothes.

A fluidity of line, in which bodies and body parts appear to meld into one another, marks Nicodemus’s work from this point forward. The resulting interpenetration of forms can be understood as a compositional device as much as a conceptual framework exploring the contours between self and other. Her painting technique is a prime example in this regard. Typically, the artist starts by drawing lines with charcoal, which she then goes over with a brush dipped into a tube of paint.19Nicodemus, in conversation with the author, January 13, 2023.She lets the brush empty as she drags it across the surface so that the resulting line skips. Afterward, she paints flat fields of color just up to the edge of these boundaries. Nicodemus’s process leaves caesuras, letting the bark cloth—or, later, the canvas—break through her lines. These lines are not separations or hard boundaries but rather a means of entwining her figures so that one emerges from another. Indeed, Nicodemus’s caesuras might be seen less as negative spaces than as pauses that make room for other kinds of encounters between her subjects, herself among them.

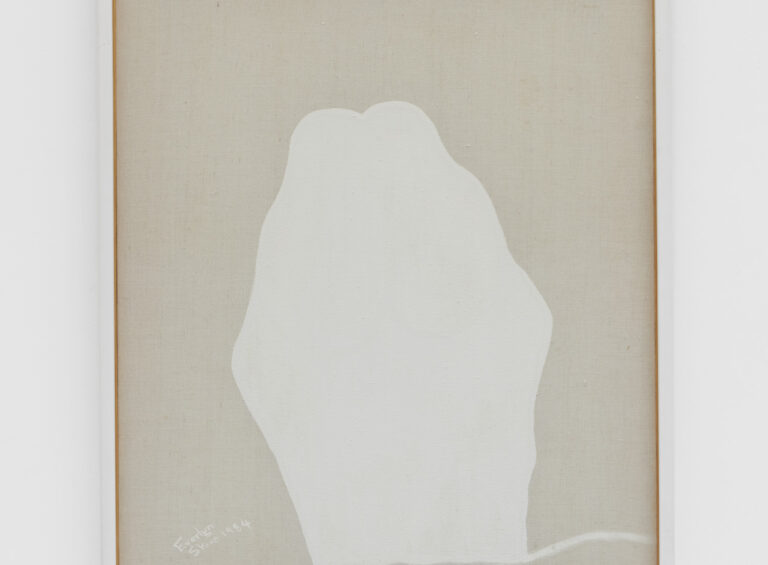

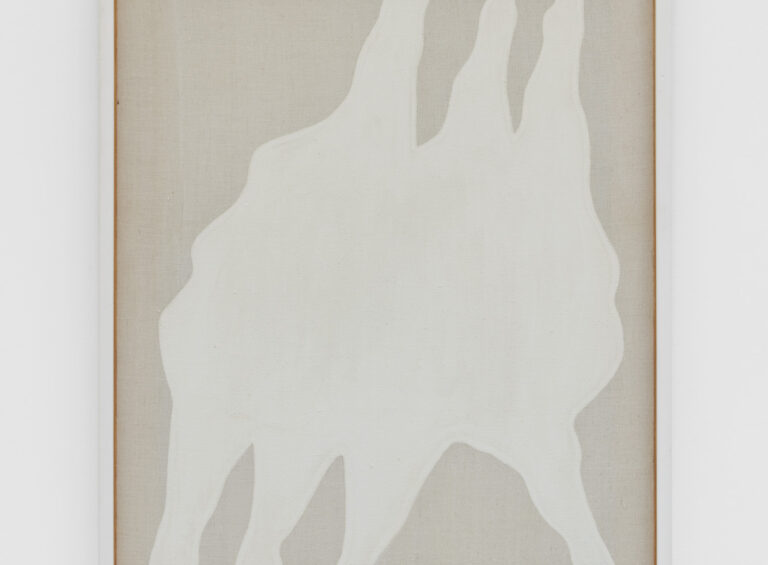

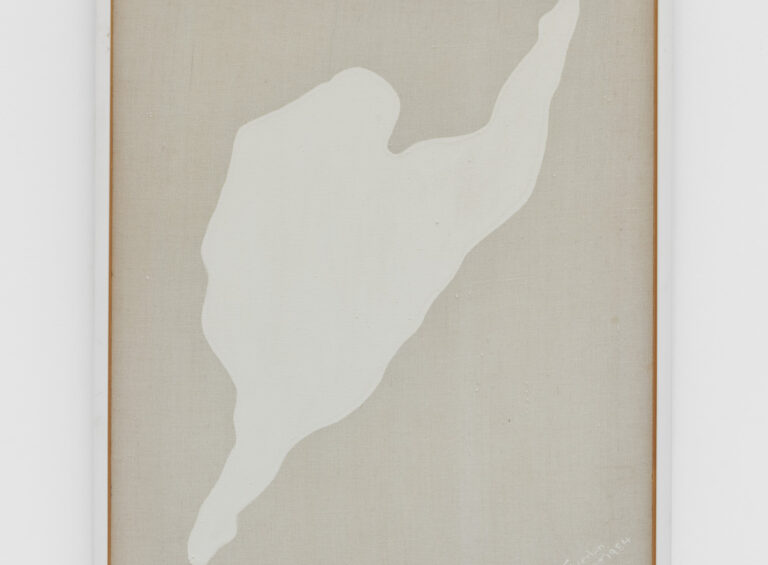

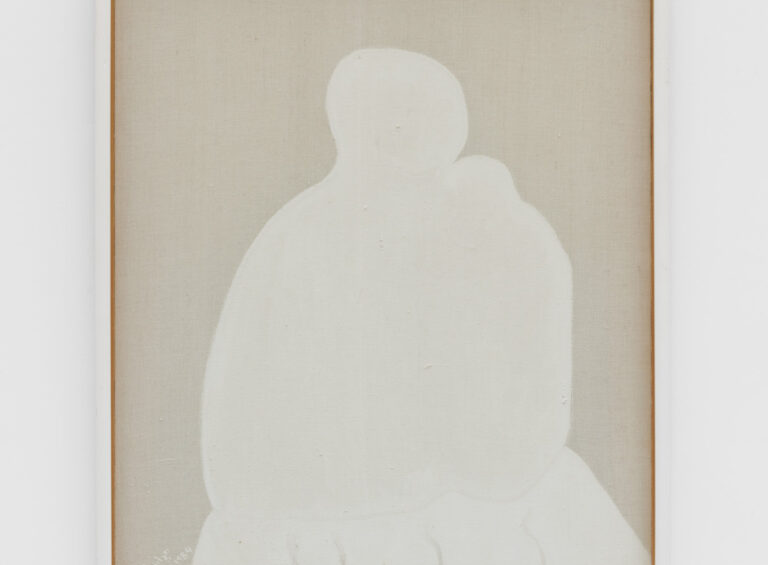

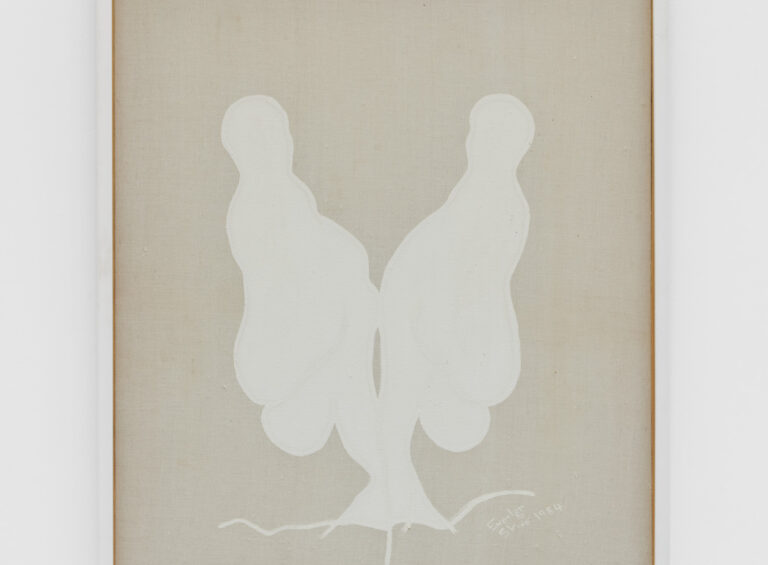

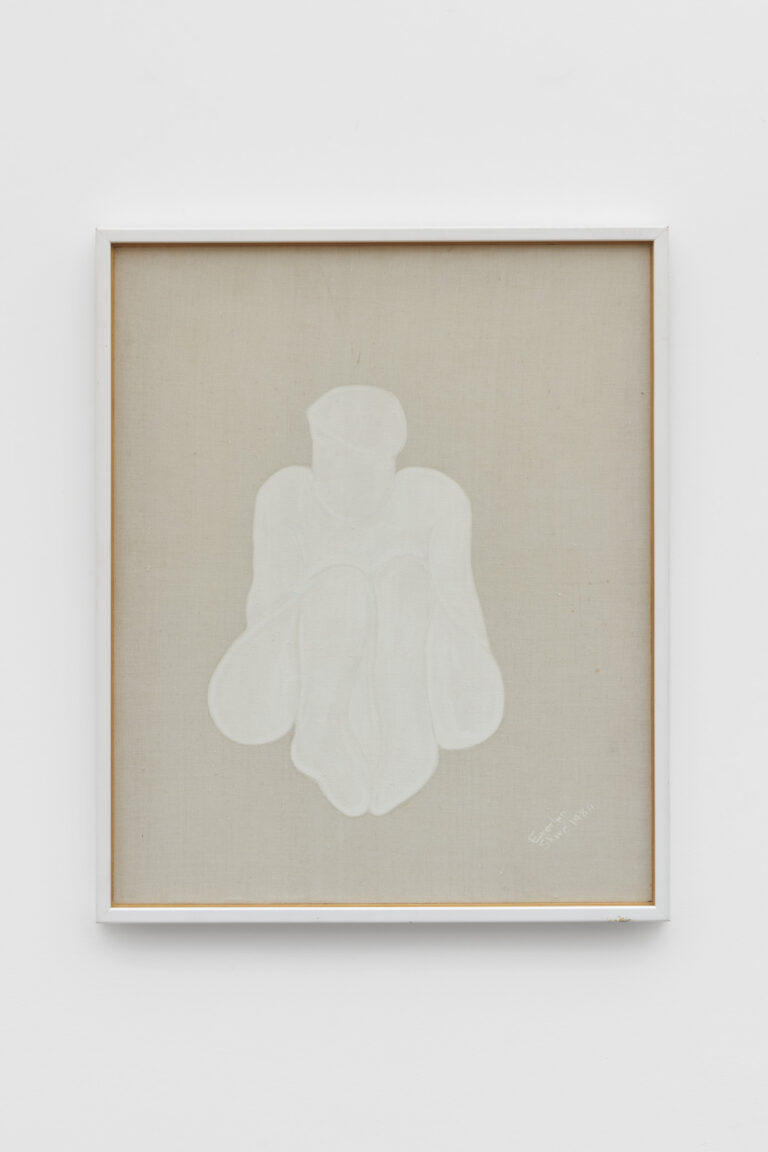

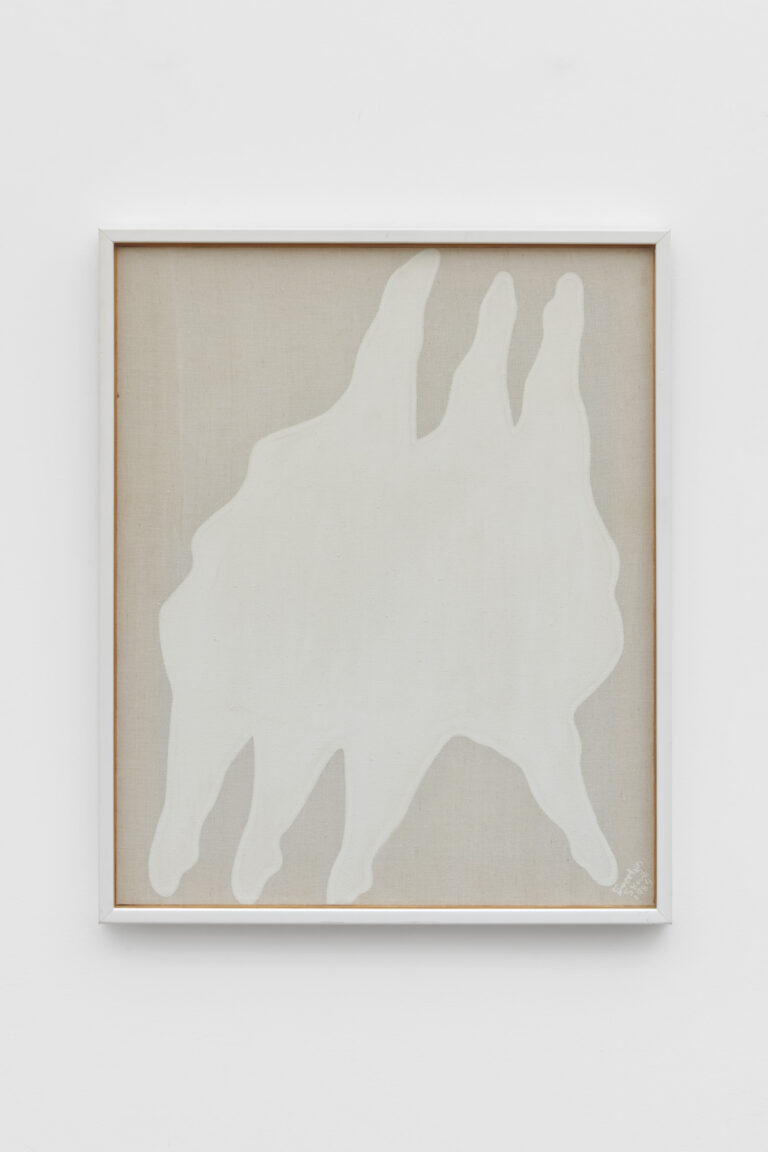

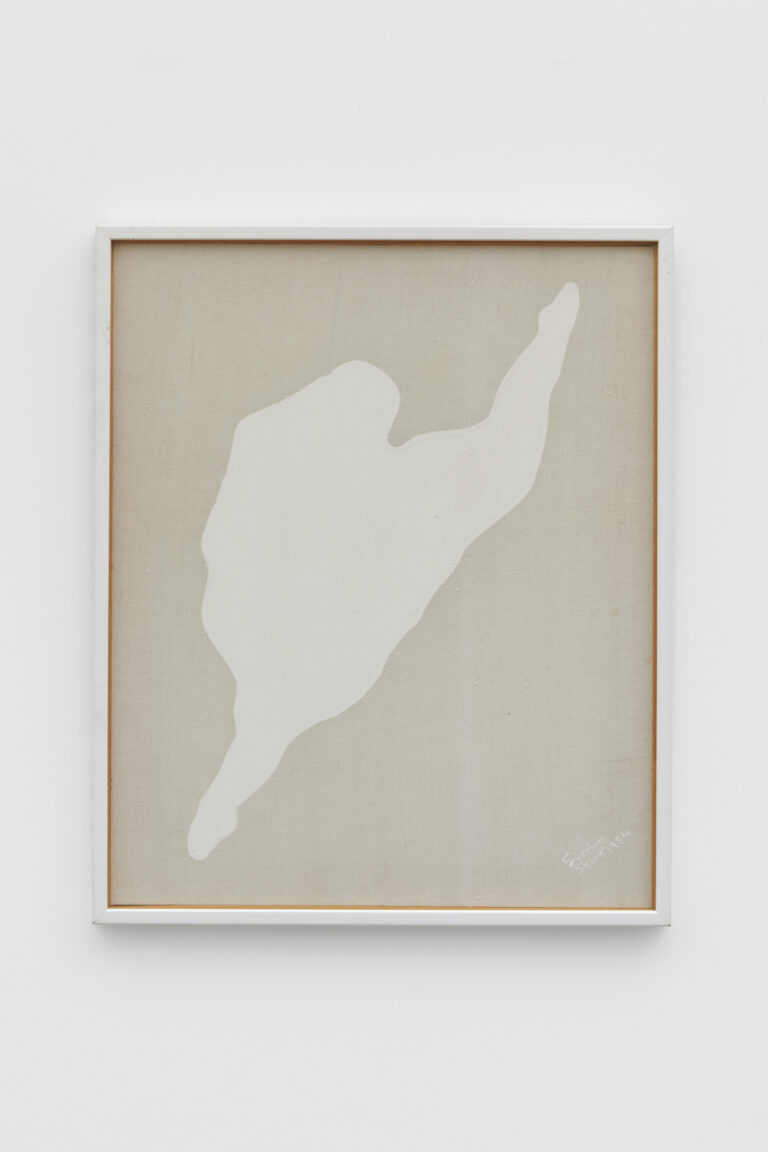

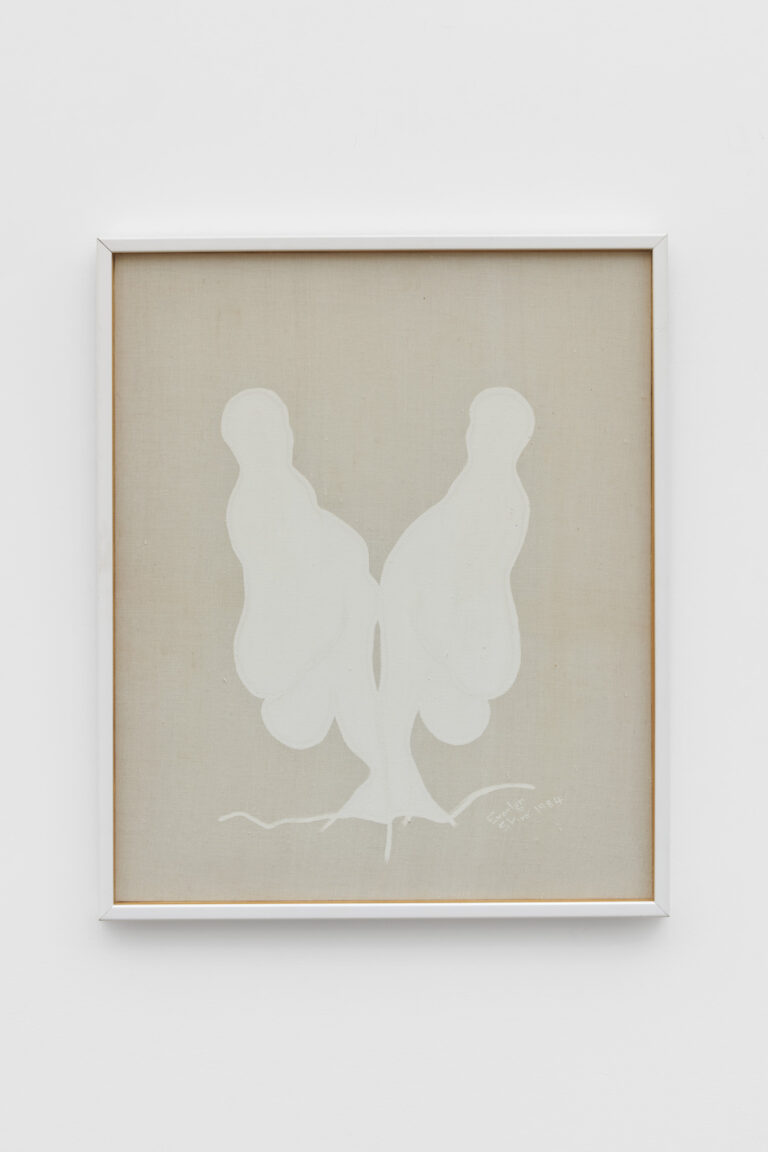

The artist’s initial works for Woman in the World, a set of six paintings titled Tystnaden (The Silence, 1984), suggest that she continued to find conceptual utility in the idea of absence after developing it stylistically in Two Black Candles. The Tystnaden paintings emerged from a lull in the conversation among the participants in Skive, the first of the three gathering locations.20The artist lists the number of participants as “dozens” in Kvinnan I Världen: Malerier og digter fra møden og samtaler i Skive 1984; Sammen med malerier og digter, 1980–84, exh. cat. (Skive, Denmark: Skive Museum, 1984), 7. Niels Henriksen generously provided translations for my citations of this catalogue.Listening later to the tapes of the group discussion, Nicodemus began to paint on antique linen she had received as a gift from her mother-in-law.21In the exhibition catalogue that accompanied the show, Nicodemus refers to her as an eighty-six-year-old Swedish woman. Kvinnan I Världen, 8. In an email message to the author dated August 22, 2024, Nicodemus confirms her identity.Her pictures are not direct translations of the women’s stories, however. As her title suggests, the moments of quiet were just as important to her. The artist saw them as pregnant pauses, conveying what could not or did not need to be said.

Featuring monochromatic silhouettes of female forms, the six compositions that make up Tystnaden evoke but never fully disclose the tenor of the wordless exchanges. The artist describes the silence as having “passed through the conversation like a white thread,” a metaphor that explains the choice of paint color as much as it points to the fine weave of the textile that she left bare in the background.22Kvinnan I Världen, 8.The outlines of the figures suggest an array of feelings, with some bodies folding in on themselves and others springing open in balletic leaps and arabesques penchées. Two women are solitary, but the remainder appear in pairs and groups. The swaths of white paint fuse them together so that, in several cases, it is difficult to make out the relationships among the parts. How many dancers, for example, are in the cluster with only seven limbs? Are the pairs of figures merging into one or splitting into two? What intimacies unite them? These questions are perhaps never meant to be answered, but they point to the gender-based affinities that the artist wanted to establish in her work at the time.23In line with the artist’s self-identified feminism, art critic Kristian Romare notes that she had “found that the silence of women, full of tears and smiles and secret understanding, was a revolt.” That revolt was, in the language of the day, the struggle for women’s liberation. Romare, “Woman in the World by Everlyn Nicodemus,” in Woman in the World II, exh. cat. (Dar es Salaam: National Museum, 1985), 3.Nicodemus further stresses this sense of commonality—in which one figure appears inextricable from another—in the corresponding poem “Women Silence.”24The entire poem is reproduced in English in Wilson-Schaef, “An African Woman Gives Us ‘Woman in the World,’” 14.According to her verse, having to hold secrets and, by extension, one’s tongue are universal undercurrents that unite women, connecting the womb, blood, and milk to the flow of rivers and oceans.

Although the formal resemblance of the figures underscores the shared moment of silence in the gathering, Nicodemus was also keenly aware that not all the women who contributed shared the same life experiences. After all, at every Woman in the World event, the participants came from different generations, class backgrounds, and professions. Several years later, the artist put a sharper point on the project she embarked on in Skive by acknowledging the limits of a feminism that does not account for the circumstances of race and geography:

The so-called First [W]orld comes to us to collect our knowledge. They put us under their magnifying glass. They study us. Giving us nothing of themselves in return. Giving nothing back of what they collect. And nevertheless talking about aid and cultural exchange.

We have to ask ourselves: Who owns the knowledge of the Third World women? We have to act to change this colonialistic one way order. I, a black woman, made an expedition to the Danish natives, to the women of Skive. I said to them: “Look at my pains, my happiness! This is me! What is it for you to be a woman?”

I gave them my knowledge, they gave me theirs. Together, we penetrated deeper. I tried to put it all in paintings and poems, not into statistics and tables. And I share my results with my sisters.25Quoted in Romare, “Woman in the World” (1986), 2.

Here, Nicodemus trenchantly borrows the language of colonial ethnography (“expedition,” “natives,” “study,” “collect”) and of anthropological analysis (“statistics,” “tables”) to reframe her own position and those of her participants. I want to draw a distinction, however, between the way in which she rhetorically presents herself in this passage and the model of the artist as ethnographer, to borrow a helpful formulation from Hal Foster, who used it to describe a slightly later set of practices from the 1990s.26Hal Foster, “The Artist as Ethnographer,” in The Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996), 171–203.Although her statement can be read as a self-aware critique, anticipating the kind of “othering” that can happen when communities become the subject of an artist’s work, Nicodemus ultimately speaks of an equal interchange in which she too gives and not just collects.

If Nicodemus introduces the idea of reciprocity first through an ironic reversal of roles, in which the African researcher goes to the European indigenes, her framing was in part informed by something that transpired between 1984, when she painted Tystnaden, and 1986, when this statement was published for Woman in the World’s final iteration in Calcutta. “Who owns the knowledge of the Third World women?” Nicodemus inquires above. She also had posed this question as the title of an article she published earlier that year in Economic and Political Weekly, a social sciences journal based in Bombay (today Mumbai).27The phrasing is slightly different in the article’s title. Everlyn Nicodemus, “Who Owns Third World Women’s Knowledge?: An Experience,” Economic and Political Weekly 21, no. 28 (July 12, 1986): 1197–201.Her account details the paternalistic attitudes and heavy-handed revisions she witnessed as a jury member and then editor for a planned volume of writings by African women sponsored by a Swedish government aid organization. What she describes, essentially, is the silencing of the contributing authors, whose texts were significantly shortened, reworked, and even retitled without their involvement. For Nicodemus, these interventions were particularly galling because the organization privileged its own agenda over the voices and stylistic choices of the writers—as well as undercut her purview as editor.

Literary critic Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s seminal “Can the Subaltern Speak?,” another text from the period, underscores the broader sense of urgency in Nicodemus’s question. Spivak first presented her ideas in 1983 at the conference “Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture: Limits, Frontiers, Boundaries,” before publishing them in 1988 and again, in revised form, in 1999.28Both versions are reprinted in Rosalind C. Morris, ed., Can the Subaltern Speak? Reflections on the History of an Idea (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010). My reading focuses on the earlier of the two, which was first published in Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg, eds., Marxism and the Interpretation of Cultures (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988), 271–313.Beyond a general time frame and the complementary formulation of their titles, Nicodemus’s and Spivak’s bodies of work are both concerned with the ways in which the West constructs a notion of the non-Western female “other” through intertwined forms of discursive and economic control that happened first through colonialism and then through global capital. (The latter of the two was a channel for the aid workers and organizations with whom and which Nicodemus crossed paths.) To boil down Spivak’s argument for the purposes of my short essay, the question is less whether the subaltern woman has agency to speak than how institutional, political, and archival structures mute or misinterpret what is said.

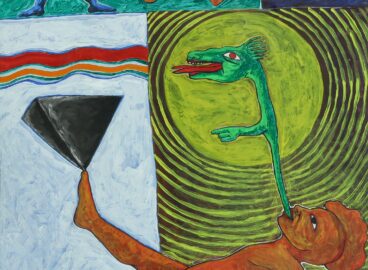

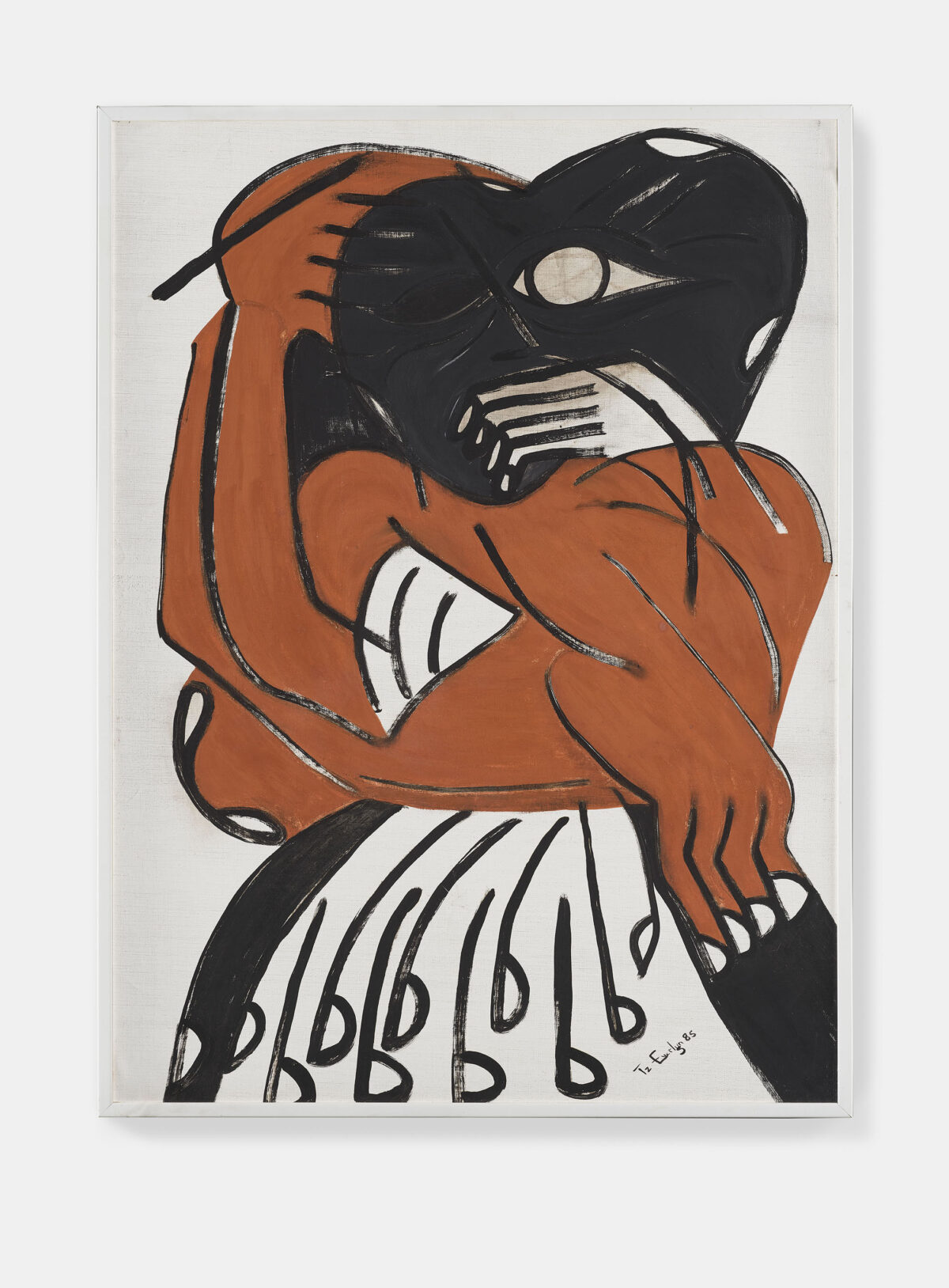

Who choses silence, and who is subject to it? Nicodemus’s work proposes different answers over the course of Woman in the World. Notably, while the artist was back in Tanzania for the second iteration of the series in 1985, the problems with the anthology of African women’s writings were coming to a head.29Nicodemus, “Who Owns Third World Women’s Knowledge?,” 1189.One of the ways that Nicodemus responded was to paint Silenced, a knot of black and brown forms punctuated with features like eyes and extremities. Emerging from this jumble of rounded shapes—heads, shoulders, elbows, knees—is a white hand covering the spot where a mouth should be. By the time she made Silenced, Nicodemus had fully developed the painting process I previously described, in which caesuras are left within and around the lines that form her compositions. In fact, barring Tystnaden, nearly all the works in Woman in the World feature some variation of this technique. That Tystnaden was the exception seems less an aberration than an acknowledgment that the pause, the absence, the silence demand critical acts of interpretation.

- 1In the case of the Tanzanian component, the conversations took place in the Kilimanjaro region, but Nicodemus painted the works in Dar es Salaam. Kristian Romare, “Woman in the World by Everlyn Nicodemus,” in Woman in the World III, exh. cat. (Calcutta: Sisirmanch, 1986), 2.

- 2Everlyn Nicodemus, “African Modern Art and Black Cultural Trauma” (PhD diss., Middlesex University, 2012), 30.

- 3Nicodemus, “African Modern Art and Black Cultural Trauma,” 30.

- 4See Ulf Hannerz, “Swedish Anthropology: Past and Present,” kritisk etnografi: Swedish Journal of Anthropology 1, no. 1 (2018): 55–57.

- 5Everlyn Nicodemus and Catherine de Zegher, “The Black Color Is Joy and Pain: A Conversation between Everlyn Nicodemus and Catherine de Zegher,” in Everlyn Nicodemus: Vessels of Silence, exh. cat. (Kortrijk: Kunststichting-Kanaal-Art Foundation vzw, 1992), 6.

- 6Everlyn Nicodemus, email message to author, August 22, 2024.

- 7Nicodemus and de Zegher, “The Black Color Is Joy and Pain,” 6.

- 8Everlyn Nicodemus, email message to author, February 22, 2023.

- 9Nicodemus and de Zegher, “The Black Color Is Joy and Pain,” 6.

- 10Nicodemus and de Zegher, “The Black Color Is Joy and Pain,” 8.

- 11For a summary from the period, see George E. Marcus and Michael M. J. Fischer, Anthropology as Cultural Critique: An Experimental Moment in the Human Sciences (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986). Also helpful is the contemporaneous Edward W. Said, “Representing the Colonized: Anthropology’s Interlocutors,” Critical Inquiry 15, no. 2 (Winter 1989): 205–25.

- 12It reads: “Here you were / laying, child / 45 cm / two-and-a-half kilos / helpless, / A whirlwind / of thoughts and emotions. / But there was / harmony in it. / This is the humanity. / Now I was a mother. / I will be a mother until my / death. / Now I am responsible. / A life.” The poem is reproduced in Everlyn Nicodemus, exh. cat.(London: Richard Saltoun Gallery, 2021), 8.

- 13Everlyn Nicodemus, in conversation with the author, January 13, 2023. See also Anne Wilson-Schaef, “An African Woman Gives Us ‘Woman in the World,’” Woman of Power: A Magazine of Feminism, Spirituality, and Politics, no. 7 (Summer 1987): 13–14.

- 14Wilson-Schaef, “An African Woman Gives Us ‘Woman in the World,’” 13–14.

- 15Everlyn Nicodemus, email message to author, August 22, 2024.

- 16For a study on bark cloth in this area, see Venny M. Nakazibwe, “Bark-Cloth of the Baganda People of Southern Uganda: A Record of Continuity and Change from the Late Eighteenth Century to the Early Twenty-first Century” (PhD diss., Middlesex University, 2005), https://repository.mdx.ac.uk/item/831w4.

- 17Nicodemus, in conversation with the author, January 13, 2023.

- 18As of July 31, 2024, the digital catalogue for the Världskulturmuseerna lists eight examples of bark cloth and several objects made with bark cloth from Central and Southern Africa, all of which are in the Museum of Ethnography collection. See https://www.varldskulturmuseerna.se/en/collections/search-the-collections/.

- 19Nicodemus, in conversation with the author, January 13, 2023.

- 20The artist lists the number of participants as “dozens” in Kvinnan I Världen: Malerier og digter fra møden og samtaler i Skive 1984; Sammen med malerier og digter, 1980–84, exh. cat. (Skive, Denmark: Skive Museum, 1984), 7. Niels Henriksen generously provided translations for my citations of this catalogue.

- 21In the exhibition catalogue that accompanied the show, Nicodemus refers to her as an eighty-six-year-old Swedish woman. Kvinnan I Världen, 8. In an email message to the author dated August 22, 2024, Nicodemus confirms her identity.

- 22Kvinnan I Världen, 8.

- 23In line with the artist’s self-identified feminism, art critic Kristian Romare notes that she had “found that the silence of women, full of tears and smiles and secret understanding, was a revolt.” That revolt was, in the language of the day, the struggle for women’s liberation. Romare, “Woman in the World by Everlyn Nicodemus,” in Woman in the World II, exh. cat. (Dar es Salaam: National Museum, 1985), 3.

- 24The entire poem is reproduced in English in Wilson-Schaef, “An African Woman Gives Us ‘Woman in the World,’” 14.

- 25Quoted in Romare, “Woman in the World” (1986), 2.

- 26Hal Foster, “The Artist as Ethnographer,” in The Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996), 171–203.

- 27The phrasing is slightly different in the article’s title. Everlyn Nicodemus, “Who Owns Third World Women’s Knowledge?: An Experience,” Economic and Political Weekly 21, no. 28 (July 12, 1986): 1197–201.

- 28Both versions are reprinted in Rosalind C. Morris, ed., Can the Subaltern Speak? Reflections on the History of an Idea (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010). My reading focuses on the earlier of the two, which was first published in Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg, eds., Marxism and the Interpretation of Cultures (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988), 271–313.

- 29Nicodemus, “Who Owns Third World Women’s Knowledge?,” 1189.