C-MAP Asia Fellow Wong Binghao continues their dialogue with artist Gaëlle Choisne about the details and entryways to her practice. This text serves as a record of Choisne’s artistic and conceptual process, and is part of the Fellow’s ongoing research about curatorial approaches to art.

Wong Binghao: In your artworks, you imaginatively congregate a diverse, cross-pollinating, and ever-changing array of intellectual and countercultural references (Black feminism, Haitian anti-colonial histories, permaculture, music, pop culture, queerness), media (sculpture, photography, video, installation, text, sound), and sensorial experiences (smell, hearing, taste, touch, emotion). You’ve described your work as a “kaleidoscopic prism with multiple entries of meanings and signs.”1Gaëlle Choisne, artist statement. You are an architect or facilitator of these permutations. How are these creative connections and networks important to your practice? What do they do or manifest?

Gaelle Choisne: This kaleidoscopic artistic prism is, of course, influenced by postcolonial cultural studies, where action and thought are open to a multiplicity of domains through which one can interconnect truths and experiences that will be authentic to historicity. I see this as a way of embracing the world and its complexity. I am especially interested in soliciting our wide range of cognitive and sensorial capacities. Before the Enlightenment, there already existed visions of the world that were less cut, chopped, and fragmented; science embraced astrology, chemistry, and divinatory arts. As beings belonging to a larger universe, we already exist within a network, in which all branches learn from each other. I work in a very large field of social and cultural experimentation, transmission, learning, imitation, and reproduction, and I translate it through my prism—a wide array of creation and encounters that always mixes with my intimate and personal stories. What interests me is, of course, how universes meet, dialogue, or reject each other. Everything lies in the experience. I am on the ground, I talk to people, I am interested in them, I listen to them, and I let them deploy their own creative field if we decide to work together. For instance, Temple of Love—Attente (Waiting; 2020) is a project I proposed for La Villette in collaboration with the Centre Pompidou in Paris. I invited students from École des Actes, a French language school for newly arrived immigrants, to produce the set design for an upcoming video work. Partnering with them during one week of a paid workshop allowed us to create a moment of intense collaboration, apprenticeship, and solidarity. Another example is Temple of Love—Atopos, presented in 2022 at MAC/VAL (Musée d’art contemporain du Val-de-Marne) in Vitry-sur-Seine near Paris, where we invited people with reduced mobility and young people from the neighborhood to attend and get involved in somatic dance sessions with choreographer and voguing yoga dancer Emanuelle Soum. I personally will be part of one of these sessions to offer moments of energetic healing and meditative relaxation.

I also create in deep relation with my spirituality and my shamanistic learning, which is growing more and more, and opens doors related to a more omnipotent intuition. In a more concrete way, I build and realize these networks with the Temple of Love project. My primary intention has always been to talk about political issues, but also to open up these issues as much as possible through forms, or situations, or devices as various as dance floors, a massage table, projection rooms, furniture . . . I put forward formal devices dealing with postcolonial and racial issues, social injustices, or issues of minoritized people, such as queer communities.

WBH: Temple of Love (2018– ) is your long-term, ongoing series of immersive and sprawling installations, each inspired by various chapters in Roland Barthes’s book A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments (1977). There are currently thirteen iterations. In what ways has Temple of Love changed (or not) since you first embarked on it, and why?

GC: Here is the manifesto of Temple of Love, which I wrote in 2018:

“Temple of love is an inclusive ecosystem around the notion of love.

It seemed essential to put forward the concept of love as a new political deal and to make it predominant in a heterosexist, racist, homophobic, transphobic society dominated by an authoritarian and predominantly white patriarchate. This radical, inverted communitarianism must be quickly challenged by cultural and governing institutions.

The “Temple of Love” project began in 2018–2019 in Bétonsalon in Paris, as a preface to a geographically indeterminate cycle.

It takes shape as an uninterrupted, multidisciplinary, systemic space.

The temple must be considered as a sacred space, i.e., linking the spaces of men and Gods and spiritual entities. This implies a questioning of our way of thinking about the world, the universe, the Nature that surrounds us.

It is of public utility.

It contains its own rules and customs.

It allows the questioning of the museum space as an entity coming from the colonial heritage.

The temple of love is ecofeminist by embodying a queer and therefore inclusive empowerment.

T.O.L is a space of resistance. It activates itself through meeting and sharing.

Temple of Love is defined through its modes of appearance and its genesis according to its invitations and its location. It is adaptable.

Roland Barthes’s original essay on love, Fragments d’un discours amoureux, in 1977, will guide us through each new chapter of the Temple of Love. I will adapt each chapter of the essay from the private to the public sphere.

T.O.L is a tribute to the invisible bodies, to minority and fragile souls and to dispossessed hearts.

I act as an artist and in very close collaboration with the curators to create a set of invitations for Russian dolls.

As an artist, I propose already existing works in the corpus of this project, new works produced for the new chapter, sometimes a new video referring to it.

The works correspond to functional sculptures acting at the crossroads of design, art, and architecture.

The functional aspect of the sculptures refers to a desacralization of art through the possibility of touching and using it.

What I like to highlight in the project—when possible—are the punctual or permanent invitations within the exhibition, of living or dead artists to whom I pay homage, who inspire me and whom I love: they are my “Luvs*.”“

Temple of Love is a backbone that allows me to generate all kinds of sculptural forms, design, and architecture, and above all, to create a real system of invitations, always according to geography, budget, institutional context, etc. The project has evolved considerably. The first chapter, which was presented in 2018 at Bétonsalon in Paris, was an ode to love and a response to racism in an overly burdensome, heteronormative, patriarchal system. The exhibition was sort of a preface to the project that allowed me to instill a system in which new ideas would be created with new invitations—in this case, artists, structures, philosophers, and activists such as Tarek Lakhrissi; Nadia Yala Kisukidi; Karim Kattan; or The Cheapest University; Carmen Brouard; Hessie; my mother, Marie-Carmel Brouard; Crystallmess; Eden Tinto Collins; Yu Araki; Arghtee; and more. The chaptered structure provides me with an axis of reflection, commented and completed by the invited figures. These figures are sometimes ghostlier than others—but they remain very important to me. It’s a way of highlighting my own creative process, which has always been done through tributes. Chance is also significant in my process, since each chapter exists by chronological iteration. I only read a specific chapter of Barthes’s book when I deploy a new T.O.L. iteration. I also never take the intimate context of Barthes’s love duo at face value, since I always retranslate it for a more social and political context—and at the end, the idea remains the same. Of course, Barthes is an important figure—the way he treats the emotional status as a white, homosexual man is revolutionary. But that being said, bell hooks is also a matrix figure of this evolving project. The way she speaks about love in the African American/Black community in the US is a major statement for me, which makes me consider her like a mother. So, Barthes is definitely not alone in Temple of Love. For instance, in 2019, for my reinterpretation of the “Adorable” chapter of A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments at The Mistake Room in Los Angeles, I proposed a tribute to Haitian classical pianist and composer Carmen Brouard and invited the students from the Colburn School of music to re-perform her pieces. I like to mix eras and styles in order to provoke third spaces of thought and creation.

WBH: Could you describe the elements in your multisensory installation Temple of Love—Love to Love for the recent New Museum Triennial? Why did you choose a refrigerator as the “main” structure for this installation?

GC: I came up with and interpreted the statement “love to love” as an expression of the ego. In the installation, I sought to embody the destructive voice of the ego inside us—which sometimes appears to be the origin of racism. I imagined a whole journey, an initiatory route, where one would shift from the raw state of an oversize ego to a state of gratitude and unconditional love. For this peregrination, I imagined a corridor interspersed with grids and barriers that represent the imaginary obstacles of our own limiting beliefs. These were only imaginary and didn’t physically protect or block anything or anyone. Other symbolic elements also appeared. Some CNC–milled sculptures made of walnut after Paleolithic Venus figures guarded the “temple”—the future joins the past to state a time that no longer exists. From time to time, perfumed smoke is emitted from one of the shipping crates in the installation. The fragrance is about unconditional love. It has a really light and fresh smell composed with some prominent spice notes, a beautiful balance between the sky and the earth. I made it in collaboration with Morgan Courtois and called it “Corps Subtiles” (Subtle Bodies). It cleanses souls and nourishes them with unconditional love. On the shipping crates, there were images from my various travels to Haiti, Brazil, and China, which were mixed with photographs from lesbian feminist archives sourced from the Internet. These crates were functional: they once contained the entire installation, and were then transformed into artworks themselves. The ghostly Madonna, a mysterious hooded sculpture dressed in chains of black roses with many balloon-like appendages, was placed opposite the refrigerator and acted as its mirror. It is the embodiment of a wounded faith, of both a masculine and a feminine energy. This installation is very spiritual. The sage branches for purification, which I wrapped myself and stuck between the grids of the fences, act as a reminder of this. They are also a tribute to the traditional use of plants in Haiti and elsewhere.

The talking “LSD” refrigerator appeared as a strange figure from the human unconscious, fed by our emotions and fears. It spoke through an androgynous voice—my own voice, which was altered—so that gender identification would not be obvious. This sculpture speaks to our anxieties, what the media feeds us, and what feeds hate—whether it be racial or not.

It is a funny and endearing but toxic character who sees a possible door to healing. My voice also acted as a collective energy healing. This is the text “spoken” by the refrigerator:

“EAT ME EAT ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME LOVE ME E. G. O. E. G. O. E. G. O. EGO

E. G. O. E. G. O. E. G. O. EGO

E. G. O. E. G. O. E. G. O. EGO

E. G. O. E. G. O. E. G. O. EGO

I don’t want to say my name. I prefer to stay anonymous.

I can be everyone and nobody.

I can’t describe myself. You know me already haha, yes, I’m those energy-consuming thoughts. I can’t feel the pain of your soul. I live for myself and only for myself.

I live for myself and only for myself. I’m satisfied when I’m right. I help you wear masks. I’m sure it’s the only way to protect you. I know it’s also a way to feed your wounds. The more you ignore me, the more I exist in you. Of course I love to be complimented and to be recognized. I’ll use every method to get more compliments hahaha hum hum hum . . . Hum, I am a stranger who has lived in your soul for so long that you have forgotten about me. You have become homeless in your own home.

You feed me easily when someone hurts you. I’m so proud, not humble at all, I love comparing everything and judging everything. Hahahaha that’s my funny game.”

WBH: How does your relationship with Haiti and the diaspora influence your work (or not)?

CG: My relationship with Haiti is quite complex. I discovered the country really late. The only connection I had to it was through my mother and my aunts, their expressions and behaviors, the Creole language used sometimes at home, and most of all the food. I went to Haiti for the first time in 2012, and it came as a double shock.

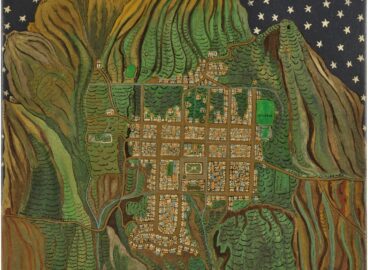

The first shock was my understanding of how my work was connected to this country without even knowing it. This organized chaos, this baroque and variegated way that I create forms and installations; the fragility of things, their ghostly presence, suspended in time and ready to disappear, in a place where elements vibrate singularly before our eyes. Colors, odors, landscapes, ways to do things and know-how—everything felt so close and yet so far.

The second shock was to discover a country still standing up after an earthquake that tore cities and families down. Haiti is brave. She never has time to recover: dangers and disasters are always at her front door. Despite multiple jeopardizing scenarios, the country has a strong and intense philosophy of life based on the importance of existence.

I’m also inspired by Haiti’s history and its stories, from urbanism to Haitian and voodoo culture. One can see these themes and topics in many ways in my work. Photography took on a new meaning when I went there for the first time. I wanted to offer images of the country that were deeper than the journalistic and touristic points of view used in Europe. Sharing and re-creating bonds between my personal, fragmented life and this Haitian life brought a lot of answers. It’s a concentrate of world diplomacy, in which one can quickly and intensely witness the direct consequences and repercussions of capitalism, international corruption, and political dishonesty. Haiti is also the embodiment of cultural blending. It is a country invented by colonization, where cultures and customs interwove themselves through slaves who came from all across Africa—but, most importantly, from Congo and Benin. This diversity and cultural interweaving take root in my work.

- 1Gaëlle Choisne, artist statement.