The Fragile Body and the Damaged Subject: A Decade of Crisis and Resistance (1998–2008)

If in the early to mid-1990s, performative actions in Armenia were, to a large extent, launched by situational or strategic collectives and groups as interventions—as correctives to institutional operations of the state and the artworld—and motivated by the desire to communicate beyond the regulated boundaries of “systems” and borders, then the late 1990s marked a shift toward individual actions, enclosure within interiority, and exploration of the body as fragile and the subject as damaged and violated. In the meantime, the earlier emphasis on text, factorgraphic strategies, ephemeral “fixations,” and interventions had been replaced by the newly available medium of video and multimedia installation often involving theatrically infused live performances focused on the body as a site of antagonism toward the social and the political, tout court. The body in these actions served as the tragic locus of the irreparable schism between nature and culture, as a site of technologically inflicted hyper-alienation. This transition from collective actions and interventions to solo performances and video was partly a reaction to the sociopolitical transformations taking place in Armenia in the late 1990s. Fermented amid social and political upheaval, these transformations were experienced as violent and tectonic.

The wild and unregulated free-market reforms of the early 1990s prepared the ground for the rise of the new oligarchy in Armenia while the Karabakh war with neighboring Azerbaijan and Armenia’s 1994 victory inflamed nationalism. Yet it was another political event that triggered a shift in general sentiment, from post-Soviet optimism to imminent disillusionment. On October 27, 1999, several gunmen entered the Armenian parliament, held the deputies and ministers hostage for hours, and subsequently killed the popular, newly elected prime minister and speaker along with six other political figures. In the aftermath of this carnage, which was almost fully televised since the session of parliament taking place at the time of the terror attack was being broadcast live on national television, president Robert Kocharyan usurped political power (which he would retain until the bloody crackdown on oppositional protests in 2008). The 1999 parliament shooting was experienced by contemporary Armenian artists as a cataclysmic event, one heralding the end of post-Soviet aspirations for the construction of a democratic nation-state led by a progressive liberal government. Politically and economically, the newly sovereign state promoting free-market reforms and liberal democracy had given way to a convenient marriage between ethnocentric nationalism and neoliberalism. The official cultural policy of the 1990s of representing Armenia as an ancient yet modern and progressive nation began to fade in the face of “one nation, one culture” rhetoric under the umbrella of Christianity, an identity that became both ideologically expedient and commercially lucrative for the new nationalist elites. Contemporary artists were relegated to the margins of this new social order, foreclosing their embrace of dominant social and cultural narratives or their artistic participation within the country’s official institutions. If, in 1998, the artist known as Sev could have an exhibition at the National Assembly triggering art critic Vardan Jaloyan’s anxiety over art’s identification with power, after the 1999 parliament shootings, the relationship between state institutions and dominant cultural narratives on the one hand and the contemporary art scene on the other could be defined only in negative terms.1Vardan Jaloyan, “Arvesty ev Qaghaqakanutyuny,” Haykakan Jamanak, April 9, 1997.

Meanwhile, the late 1990s were also marked by a triumph of postmodern mediatization of the public sphere, where the world onscreen came to be perceived as more real than the social reality, which was replete with contradictions.2I trace this transformation in Angela Harutyunyan, “The Real and/as Representation: TV, Video, and Contemporary Art in Armenia,” ARTMargins 1, no. 1 (February 2012): 88–109. In contrast to the deceptive spectacle of media representations, contemporary artists used the technology of video to signify resistance and “truth.” Here, the performing body being screened for display served as a conduit to an authentic reality, one beneath and beyond the cultural “screen.” Video as a medium of subversion, truth, and exposure in Armenia had its roots in the early 1990s in the form of sexually explicit content on VHS tapes.3Vardan Azatyan, “On Video in Armenia: Avant-garde and/in Urban Conditions,” Previously published on www.video-as. org/project/video_yerevan.html. The link is no longer accessible. The proliferation of video was technically possible because the Armenian Center for Contemporary Experimental Art (ACCEA) imported cameras, DVD players, TV monitors, and projectors, which it then made available to artists, while the theatrical and ritualistic pathos of performative practices found nourishment in theatrically infused multimedia performances by New York–based Iranian Armenian artist Sonia Balassanian, whose aesthetics were promoted by ACCEA’s theater department.

The triangulation of theatrical video-performance, the conception of the fragile body as a site of violence, and the belief in art as a means of resistance was crystalized in works made by David Kareyan between 1999 and 2007. From ritualistic sacrifice (Dead Democracy, 1999) to eating the victim’s flesh (Eucharist-450, 2000) and splitting bones with an electric saw (Gastritus, 2002), Kareyan displayed the body, often naked, on a video monitor set among incongruent materials such as earth, plants, bones, and fleece to signify the subject’s alienation and estrangement from nature (fig. 1). Kareyan’s work of this period counterposed art’s promise of de-alienation with the false sublation of alienation within the social sphere—where the technologies of the cultivation of the self in a society in which standardized consumerist desires and behaviors promised fulfillment but instead mass-produced conformity. These social technologies of desire shaped the body as an image of power (in edified, upstanding form), while at the same time, subjugated it. The effects of political control and consumerism were inscribed on the body of the normative subject, whose complicit performance of militarism, patriotism, and conservative morality naturalized patriarchal domination. These ideologies produced autoerotic subjects whose frustrated desire could only be expressed through a primordial return to mud (The World Without You, 1999) or invoked through the impossible return to murder and incest (Sweet Repression of Ideology, 2000).

The culmination of these series of videos and performances was Kareyan’s No Return (subtitled Suicide for Eternal Life, Oral Hysteria, Speech Capability Paid [for] by Madness) of 2003.4The work was performed, for the second time, at the 3rd Gyumri Biennial in 2002, after its initial presentation at the ACCEA in the same year, and ultimately transported to the Venice Biennale in 2003. Realized in collaboration with curator Eva Khachatryan, this three-channel video installation was composed of a central screen showing a Bill Viola-esque video of Kareyan in a white nightshirt digitally superimposed on fire (in different versions of the work, the images on the screens vary) and two side screens showing montages of found footage from documentary films and world news reports of various recent turbulent events superimposed on politically charged signs and words. An audio piece composed of electronic bits and lyrics by early twentieth-century Armenian poet and writer Yeghishe Charents played in reverse accompanied the videos, as did a live performance involving seven female figures, most of whom were members of the punk band Incest, dressed up in hooded black gowns and drumming on tin plates and logs (fig. 2).

These works echoed Sonia Balassanian’s multimedia theatrical performances of the same period, which were infused with myth and ritual. Balassanian’s performances, in turn, referenced Armenian ecclesial traditions, enacting victimhood, sacrifice, and various rituals of domination and subjugation (Shadows of Dusk and Collapse of Illusions, 2000; and There Might Have Been, 2003, ACCEA). The construction of a total environment that overwhelmed the audience with its production of affect combined video projection, ready-made objects, voice, music, performance, and other media and encompassed the entirety of the viewer’s sensorial sphere, a Gesamtkunstwerk of sorts. Often, such as in Collapse of Illusions, this total environment also functioned as a grand theatrical setting that accommodated other artists’ performances (including those by David Kareyan, Karine Matsakyan, Sona Abgaryan, and Diana Hakobyan, among others). Collapse of Illusions was formed through multiple discrepant activities performed by subjects in solipsistic self-enclosure and constituted a negative side of reality in which everything was as it is in the social world but nonetheless dysfunctional, futile, and completely deplete of time and context. Sewing, knitting, hammering nails, dancing, and “cooking” book pages in tar were performed in a dystopic, atemporal landscape littered with media images, objects, artworks, and debris.

Several artists in the early 2000s produced videos and performances exploring the body as a fragile yet subversive locus of sexuality, eroticism, and desire. Tigran Khachatryan’s videos pursue sexually explicit content montaged onto signifiers of youth subcultures and remixed with ready-made references to film and pop culture. Repetitive and futile masturbatory gestures—or their metaphorical representation through juxtaposition of image and rhythm—often follow the structure of male orgasm (such as in the “explosive scene” of the gas stove burning and being extinguished in Romeo, 2003). This image of the virile subject appears alongside the figure of a male subcultural antihero as an average representative of a bored and jaded generation (Stakler, 2004). In a 2002 performance titled Bread and Cheese, filmed in the medieval monastery Ayrivank, the artist, dressed as a punk soccer fan mimicking a soccer player from the Turkish national team (Umit Davalan), approached a miniature football field lined with white paint, sat in front of the camera, and proceeded to eat bread and cheese (fig. 3). As viewers of the recording of the performance soon realize, the camera positioned in front of the artist was not filming the performance but rather displaying a soccer game. The action of eating bread and cheese evokes a common Armenian adage that one must eat a lot of bread and cheese in order to become an adult.5The work is a direct commentary on the notorious Armenian sports commentator Suren Baghdasaryan’s remark that Armenians should eat a lot of bread and cheese in order to compete with the Turks. The saying is often used in a derogatory sense to indicate that someone needs to grow up or mature. This “rite of passage” experienced by the young punk recalls an ironically enacted oedipal patricide that took place at a site of patriarchal authority, that is, on church grounds. However, instead of assuming the father’s place after the symbolic murder, Khachatryan’s male subject remains forever juvenile.

If the male body in Khachatryan’s work is at times virile and sexually provocative (such as in his series of “Garage” film productions including Romeo, 2003; Theodicy, 2005; and Entertate, 2010),6The series mixes found footage with the artist’s own recordings and often takes its cue from iconic films such as Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979), Piero Paolo Pasolini’s Arabian Nights (1974), and Sergei Parajanov’s The Color of Pomegranates (1969). and at other times bored and indifferent, in Harutyun Simonyan’s video performances, it is fragile and vulnerable. Simonyan’s performances are framed in a decontextualized and compressed space in which the naked artist assumes a fetal position onscreen—as in a womb (Untitled, 2001). Simonyan’s naked body dances, slips, and tumbles in a room covered with black linoleum and smeared with Vaseline (Untitled, 2003), it falls asleep (Sleep, 2001), and it performs the feminine work of sewing and attempts to don a feminine dress that is too small (Untitled, 2001; fig. 4). The sexualized male body is masochistically exposed to voyeuristic scopophilia as the audience “infiltrates” the artist’s private space. Yet, masochistic exhibitionism and exposure here do not unambiguously grant the viewer visual control over the fragile body; the subject is also protected and sheltered by the screen/womb in the fantasy of a return to its maternal origin. In Lusine Davidyan’s video Untitled (2003), the embryonic state unfolding on the TV monitor is not a prelapsarian fantasy of the whole and undivided subject but rather the horror of certain and predetermined death. An abstracted form of a body flickers onscreen while a black text on the white wall behind it issues the verdict “Embryonic Death Embedded in Your Body,” echoing the lyrics of heavy metal band Slayer: “Embryonic death, / Embedded in your brain.” The temporality of Simonyan’s work is a regression to the ahistorical and pre-subjective time before birth, to the mother’s body, while Davidyan’s is that of the anterior future—that is, of a future that will have happened in the past.

If the above-described works confine the body to a claustrophobic self-enclosure refusing any relationality or “outside,” other artists of the same generation explore the intersubjective dimension of bodily communication. In Sona Abgarian’s videos of the early 2000s, friendship is conceived as a medium of intersubjective exchange in which play and violence, communication and its failure, appear as rudimentary forms of sociality. In Untitled (2001), two female subjects (the artist and her friend, Astghik Melkonyan) assume a four-legged position and engage in a play of love and envy, empathy and violence, as they circle, hug, and bite each other (fig. 5).

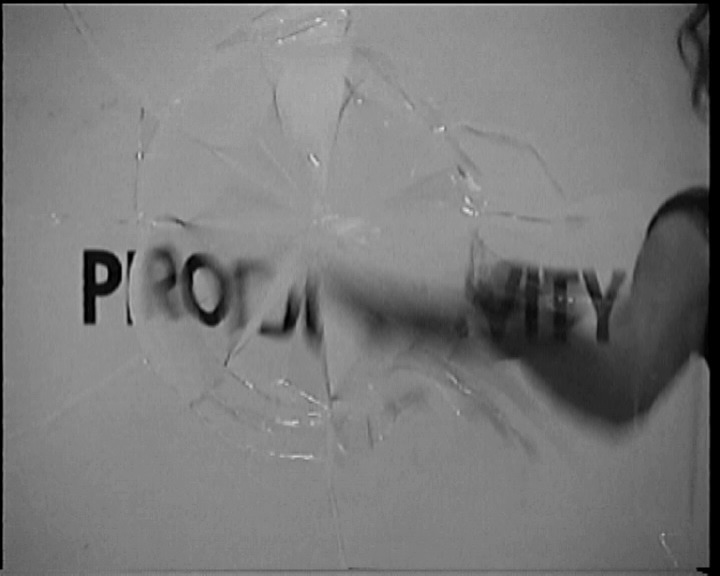

Diana Hakobyan’s videos of the early 2000s position the active body as disruptive to the induced passivity of media spectacle and consumerism as she engages with the deconstruction of the rhetoric of mediatized images and social clichés. In I Can’t Believe in Your Dreams (2002), the artist is seen skipping rope in a series of close-ups (of her face, abdomen, chest, or legs), while her action is rhythmically interrupted by shots of a hammer smashing panes of glass inscribed with social ideals such as “Collaboration,” “Productivity,” “Success,” and “Imagination” (fig. 6). In another, the artist boxes against a pane of glass covered in illegible scribbles in red paint. This figure of the female artist as warrior against social clichés and consumerist desires can be traced to an earlier work by Karine Matsakyan. In 1995, as part of her solo exhibition Triumph of the Consumer at Charlie Khachatryan Gallery, Matsakyan walked into a butcher’s shop with a toy gun and “fired” at hanging flesh (Suicidal Tendencies, 1995).

Anna Barseghian’s 1999 performative photograph taken in a men’s bathroom in the Grand Théâtre de Genève intervenes in the sexual division of intimate spaces. The image shows the artist dressed in a black ceremonial costume, like that worn by a widow or a theatrical performer (fig. 7). She is standing still and upright at a urinal, her back to the viewer. The contrast between the artist’s stern and austere appearance and the “hooliganism” of the act, the assumption of a phantasmal phallus by a conservatively dressed female figure, juxtaposes two incongruent notions, thus estranging the social reproduction of sexuality as it is conducted through the demarcation of segregated sights and signs.

Up until the early 2000s, these actions were not overtly framed as feminist—with the exception of Barseghian’s work, among a few others.7Heriqnaz Galstyan and Arevik Arevshatyan were also perhaps exceptions. Arevshatyan articulates feminist concerns in her 1995 work The Belt. A shift in framework took place in about 2002–3, when Sonia Balassanian on the one hand and Austrian curator Hedwig Saxenhuber (who was visiting Yerevan) on the other, encouraged an explicitly feminist framing of women artists’ work concerned with the social reproduction of sexual divisions, gender roles and anti-patriarchal manifestations, and the body. The feminist exhibitions Women’s City curated by Arpine Tokmajyan, Heriqnaz Galstyan, and Narine Zolyan in 2004 and Rocks Melting in the Depth of the Earth in 2004 and Women’s City by Eva Khachatryan in 2005 were testament to this shift toward revealing explicitly feminist concerns through a language and discourse of difference and identity characteristic of US third-wave feminism of the 1970s and 1980s. First displayed at the festival Rocks Melting in the Depth of the Earth, artist and musician Tsomak’s video juxtaposes her frantically dancing naked body with a video of a dancing stripper filmed in a club in Yerevan, whereas Sona Abgaryan’s work shows the artist buttoning her blouse, taking it on and off in awkward movements, as a first-person account of violence against women runs in the subtitles.

Astghik Meklonyan’s work Bokhcha (2004) likewise engaged with traditional feminine roles and tasks. But this engagement was not guided by a subversive reperformance of sexual roles. Rather, it was carried out through an exaggerated over-performance in which the female subject became the object of her own labor. In Bokhcha, the artist’s body was wrapped and de-subjectivized and barely visible among other colorful and patterned wraps as she moved slowly through them (fig. 8). These wraps made of blankets and sheets functioned as signifiers of the household labor undertaken by women, while also evoking the experience of displacement and migration. Indeed, “bokhcha,” a Turkish word assimilated in Armenian slang, designates a self-made wrap that immigrants, nomads, travelers, and the displaced use to carry their belongings.

The dominant paradigm of Armenian performative art practices in the late 1990s and early 2000s could be construed as one of a critical deconstruction of socially imposed gender roles, sexual identities, and forms of subjectivization. In this context, Azat Sargsyan’s performative interventions propose another strategy: not to rearticulate the body, identity, and subject in order to subvert dominant discourses but rather to annihilate the very material upon which this ideology conducts its wicked schemes—that is, the subject itself. In Azat (free) Hanging on Freedom Square on the Independence Day (2000) the artist hung upside-down from a streetlight (fig. 9). The title of the action plays with the artist’s name Azat which in Armenian means freedom and is repeated in the name of the iconic Freedom square where the demonstrations for Armenia’s independence took place throughout the late Soviet period. According to the artist, through the action he was commenting on independent Armenia’s actual dependence upon larger geopolitical forces.8E-mail correspondence with the artist, 23.08.2024. A photograph shows the artist anthropologically opposite the human orientation and iconographically in contrast to the statue of Armenian composer Alexander Spendiaryan in the background on the right. This reversal or repositioning as a means of annihilation of the subject was performed in Welcome (1999), which took place at the exhibition After the Wall in Stockholm in 2000 and in 2002 at the São Paulo Biennial.9After the Wall: Art and Culture in Post-Communist Europe, Moderna Museet, Stockholm, October 16, 1999–January 16, 2000; and São Paulo Biennial, Fundação Bienal de São Paulo, Parque Ibirapuera, March 23–June 2, 2002. This time, the artist positioned his body horizontally as a doormat and lied there for two hours to mark the entrance to the exhibition space. This willful self-objectification as a lowly, abject doormat beneath visitors’ feet marked a desire for the obliteration of subjectivity, a desire that reached its extreme in Azat’s subsequent performances involving death and the politics of its commodification.

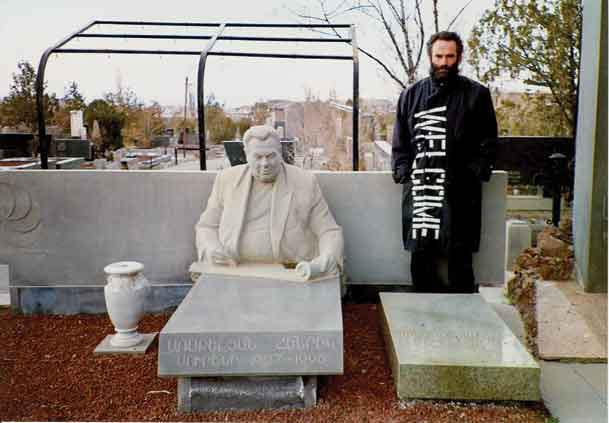

In Welcome to Armenia, Museum Under Heaven (2003) commissioned for the exhibition L’environement du corps génétiquement modifiable, curated by Barseghian and Nazareth Karoyan, the artist studied the economy of cemeteries, especially the real-estate speculations through which municipal burial grounds in Yerevan spread toward residential neighborhoods. They had become “last destinations” for expat Armenians who lived abroad but dreamt of being buried in their homeland. Azat showed funerary accessories across the city, including a guide to the cemetery “Armenia,” placing the country itself as a cemetery under heaven. The artist, wearing a black garment with a white painted inscription “Welcome,” was photographed next to funerary statues and tombs (fig. 10). His identification of Armenia as a place of death exposed the commodification of this myth and positioned it as an object of touristic consumption.10Vardan Azatyan, “Azat Sargsyan, Welcome to Armenia,” in L’environnement du corps, exh. cat. (Geneva: Metis Presses, 2005), 50. Continuing identification with death and dying, this subject was finally obliterated in the impossible act of witnessing one’s own funeral (the Gyumri Biennial of 2008116th Gyumri Biennial for Contemporary Art, September 7–21, 2008.).

Azat’s works recall the 1980s practices of unofficial artists of the Soviet Union, for whom disappearance and death became a means of escaping the watchful eyes of the Soviet apparatus. But, paradoxically, this self-annihilation was also a road to absolute freedom (“Azat” in Armenian means “free”). Enacted in the 2000s, Azat’s anachronistic dissidence was a reminder of the ghostly reverberations of a world that had supplied negative content for the conception of art as a free space for dreaming, a conception formative for contemporary art in Armenia and performative practices within it. This world was the disappearing landscape of Soviet modernity. In the 2000s, when identification with the social context could no longer be secured, the artist’s social function could no longer be affirmed. To be sure, amid conditions of increasing alienation, the imaginary world of artistic creations became a shelter of sorts, a compensatory mechanism, while the artist became ever more marginalized in the context of rampant nationalism and neoliberalism. The return of Armenia’s first president Levon Ter-Petrosyan, a liberal democrat, to politics in 2007 opened up a space for renewed participation in politics and public life for artists, a space that was soon to be violently shut down as the outgoing president Kocharyan announced martial law and, on March 1, 2008, issued a deadly crackdown of the opposition.

Editors’ note: Read the Introduction and Part I of this series here, and Part II here.

Author’s note: The research for this three-part article was commissioned by ARé Cultural Foundation in 2022. Some parts are informed by earlier research conducted for my monograph. See Angela Harutyunyan, Political Aesthetics of the Armenian Avant-Garde: The Journey of the “Painterly Real,” 1987–2004 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017).

- 1Vardan Jaloyan, “Arvesty ev Qaghaqakanutyuny,” Haykakan Jamanak, April 9, 1997.

- 2I trace this transformation in Angela Harutyunyan, “The Real and/as Representation: TV, Video, and Contemporary Art in Armenia,” ARTMargins 1, no. 1 (February 2012): 88–109.

- 3Vardan Azatyan, “On Video in Armenia: Avant-garde and/in Urban Conditions,” Previously published on www.video-as. org/project/video_yerevan.html. The link is no longer accessible.

- 4The work was performed, for the second time, at the 3rd Gyumri Biennial in 2002, after its initial presentation at the ACCEA in the same year, and ultimately transported to the Venice Biennale in 2003.

- 5The work is a direct commentary on the notorious Armenian sports commentator Suren Baghdasaryan’s remark that Armenians should eat a lot of bread and cheese in order to compete with the Turks.

- 6The series mixes found footage with the artist’s own recordings and often takes its cue from iconic films such as Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979), Piero Paolo Pasolini’s Arabian Nights (1974), and Sergei Parajanov’s The Color of Pomegranates (1969).

- 7Heriqnaz Galstyan and Arevik Arevshatyan were also perhaps exceptions. Arevshatyan articulates feminist concerns in her 1995 work The Belt.

- 8E-mail correspondence with the artist, 23.08.2024.

- 9After the Wall: Art and Culture in Post-Communist Europe, Moderna Museet, Stockholm, October 16, 1999–January 16, 2000; and São Paulo Biennial, Fundação Bienal de São Paulo, Parque Ibirapuera, March 23–June 2, 2002.

- 10Vardan Azatyan, “Azat Sargsyan, Welcome to Armenia,” in L’environnement du corps, exh. cat. (Geneva: Metis Presses, 2005), 50.

- 116th Gyumri Biennial for Contemporary Art, September 7–21, 2008.