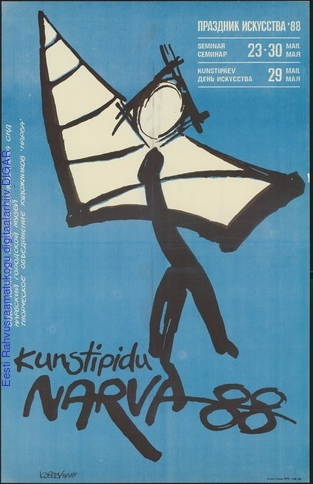

In May 1988 unofficial artists from across the Soviet republics gathered in Narva, Estonia, for what would be one of the last Soviet art festivals and yet one of the first such events to celebrate experimental performance art.1Throughout this essay, I use the term “unofficial artists” to refer to a generation of artists practicing experimental performance, installation, and street art outside of official Soviet institutional forums. However, many of the artists whose work I discuss here received training across the republics or participated in Soviet-wide artistic exchanges through official funding channels. The Festival of Art “Narva-88,” as it was called, was held on the threshold of the Soviet empire at Narva Castle, the Estonian castle fortress facing the Ivangorod Fortress—its Russian counterpart across the Narva River—and on the beach by the Baltic Sea, which surrounds the country to the north and west. By this time, Mikhail Gorbachev’s launch of perestroika (restructuring) reforms to promote economic “acceleration” had waned into stagnation as glasnost (openness), the promotion of cultural expression, made way for sovereignty claims throughout the Soviet republics. Held against a backdrop of dissident mobilizations ranging from the Karabakh conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan in February 1988 to a series of environmentalist independence campaigns in the Baltics in 1986–87, Narva became a flash point in the lead-up to the empire’s collapse.2For more on nationalist mobilization amid the collapse, see Mark R. Beissinger, Nationalist Mobilization and the Collapse of the Soviet State (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 47–102.

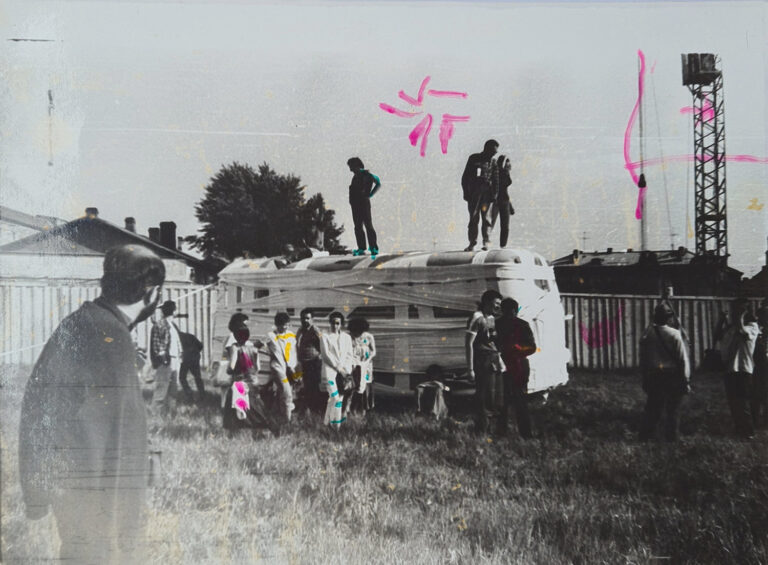

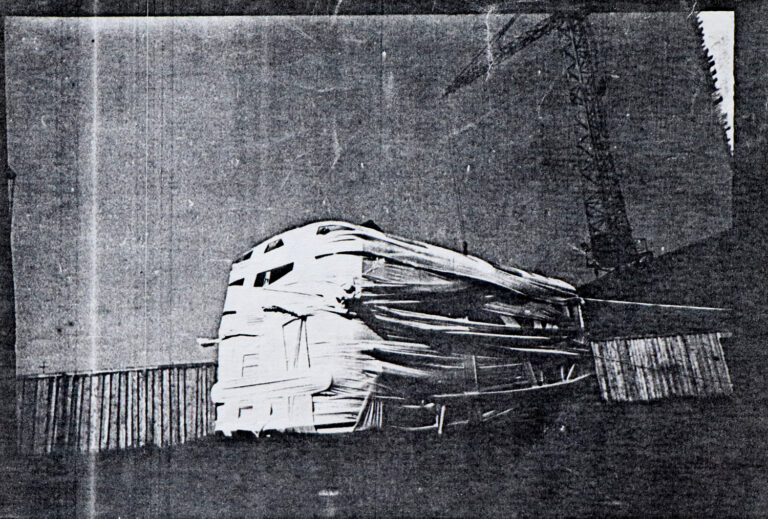

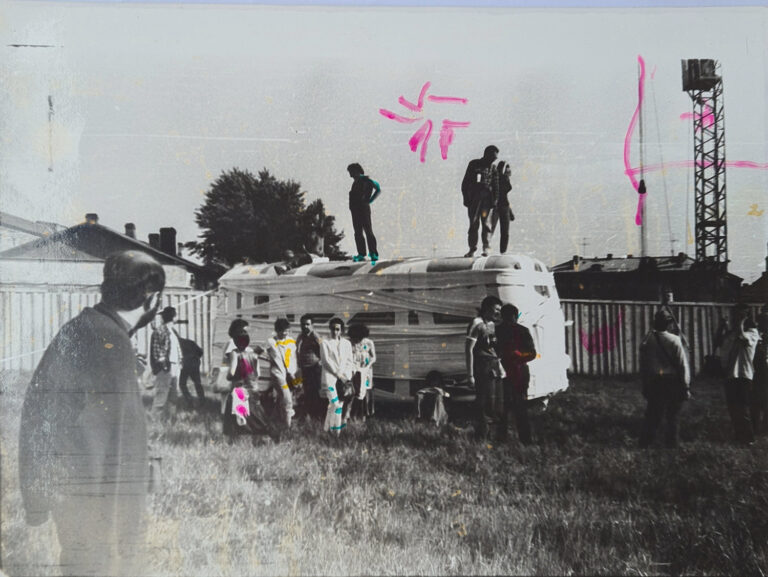

One local paper described the large-scale, mixed media assemblage constructed on the lawn near the castle fortress as “installations filled with expression and sarcasm—human statues in wrestling poses tightly bandaged with strips of fabric, as if trying to escape from their binds, and next to them, a broken-down bus waiting dejectedly and hopelessly—the desire for action turned into inaction.”3Curator Ninel Ziterova—with the department of culture of Narva Gorispolkom (the city’s executive committee) of the Estonian SSR—was one of the official organizers of the festival. This quotation is from Ziterova, “Prazdnik Iskusstva v Narve,” Sovetskaia Estoniia 158, no. 8 (1988): 2. Translation mine. Sick Bus and its accompanying figures were created by Lia Shvelidze (born 1959) with other members of the unofficial Georgian art collective—the Marjanishvilebi.4The name “Marjanishvilebi” was derived from the group’s clandestine studio in the Marjanishvili Theatre. See Vija Skangale, “An Underground Bridge to Georgian Collectiveness: Finding a Tribe through Collective Trauma,” post: notes on art in a global context, posted July 15, 2022, https://post.moma.org/an-underground-bridge-to-georgian-collectiveness-finding-a-tribe-through-collective-trauma/. In the 1970s abstract artists such as Avto Varazi (Georgian SSR) straddled official and unofficial spheres as they were occasionally paid to show work in the National Gallery (one of the only official art spaces at the time) while at the same time helped to organize apartment exhibitions. The asssemblage was the group’s first major work in an international public Soviet forum.5The installation at Narva was followed the same year by group exhibitions at the Galerie Eigen + Art in Leipzig and the Fransuaza Friedrich Gallery in Cologne and, in 1989, at the Black and White Gallery in Budapest and in the exhibition—Georgian Avant-Garde 80s— at the State Ethnographic Museum in Leningrad. Incorporating local found materials, the defunct Soviet bus parked in the castle yard was wrapped in cheap medical bandages, presented as not only a monument to wounded or arrested progress, but also a site of complex and conflicted feelings. The human figures captured a mix of rage, sarcasm, and raucous joy, expressions that were, in turn, concealed by the bandages.

Moreover, Sick Bus, as a metaphor for the stalled Soviet economy, seemed to serve as a counter-monument in its sideward glace across the Russian-Soviet and European borders to The Point Neuf Wrapped (1975–85) by Bulgarian-born Paris-based artists Christo (1935–2020) and Jeanne-Claude (1935–2009). However, this critique of monumentality not only envisioned the specter of Soviet collapse, but also, more crucially, exposed the uncertainty of socialist belonging, a duality made palpalable in the uncomfortable conjunction between the work’s experimental form and its staging amid the official festival environment of state-sanctioned collectivity and optimism. Literally put under wraps, the mock-monument in the yard of the fortress under the banners of the Soviet festival drew viewers’ attention to the surface of its components—the texture of overlapping bandages. The symbolic object of the broken-down Soviet bus was transformed into a textural sculpture—a form that took shape in the contours of the cheap fabric covering it. In contrast to the official festival’s form, the installation represented an experimental and improvisational practice—figures suspended between political and social worlds—exposing the space of transition through the sensuous surface of the forms and the range of conflicted and muted emotions they evoked.

Sick Bus also highlights the transition in artistic value during the late Soviet period, whereby unofficial art in the Soviet Union began to draw support in part from state funds. Yet as the inaugural Sotheby’s sale of unofficial Soviet artworks held only a few months later, in July 1988, suggests, experimental works were also already beginning to garner currency in a global marketplace—albeit their acquired value traded in Euro-American fantasies of the “underground” scene of the almost “former East.”6See Sotheby’s, Russian Avant-Garde and Soviet Contemporary Art, sale cat., Moscow, July 7, 1988.Narva-88’s liminality between the collapsing Soviet empire and the accompanying social, economic, and ideological transitions exposes a diverse portrait of this complicated moment, one that prefigures the term “post-Soviet.”

In our current moment, narratives seeking to explain Putin’s violent invasion of Ukraine have raised necessary skepticism with regard to the idea of “post-Soviet.” Following a question set in motion since the dissolution on December 26, 1991, as to whether the “post-” in “post-Soviet” should also be read as “postcolonial,” the invasion has both confirmed that narrative and, at the same time, somewhat paradoxically revealed a persistent tendency to envision the region homogeneously, conflating Soviet with Russian—and Soviet society with an impenetrable ideological and cultural Cold War gaze. In the 1990s, “post-” marked a hard break—the rupture of a geopolitical, economic, and ideological worldview that Francis Fukuyama has described in the totalizing idiom of the “end of history.”7See Francis Fukuyama, “The End of History?” National Interest, no. 16 (Summer 1989): 3–18. But this moment should have instead called for a passionate rewriting. Staged amid a messy and uncertain moment on the eve of the collapse of the Soviet empire, Narva-88 exposes the diversity and complexity of this space-time. It asks what would it look like to speak of the collapse not from the vantage of “post-,” but instead as a transitional moment that forged radically new modes and logics of belonging, violent rupture, and flourishing from within multilingual, aesthetically and culturally diverse, and affectively conflicted spaces that shaped the transition. It complicates a Euro-American vision of the Soviet Union as a homogeneous political and social mass located in a Slavic-Russian metropolitan center. It questions how one can document the sociopolitical transition from the indeterminacy and uncertainty of the present moment of its unfolding—as opposed to from the finality connoted by “post-” or the ethno-cultural homogeneity suggested by “Russian”—to the illumination of a set of complicated attachments to Sovietness. This essay seeks to open one such vantage by exploring Narva-88 as the site of experimental performances of alternative logics of belonging that both precede and exceed the so-called post-Soviet.

While many studies of performance in the context of late Soviet neo-avant-garde art have focused primarily on Russian and male artists—from the Mitki to the Moscow Conceptualists—Narva-88 illuminates the liveliness of the Soviet art scene in the late 1980s beyond the Russian metropolitan centers of Moscow and Leningrad. As Kyrgyz artist Gulnara Kasmalieva (born 1960) remembers, the festival’s guest list took shape through personal connections she made on Soviet-funded trips through the Caucasus and during her tenure in Estonia for studies in printmaking in 1987, exposing more broadly how informal networks, seminars, and exchanges animated connections across the republics over the course of the 1970s and 1980s.8Gulnara Kasmalieva, interview by Leah Feldman, July 19, 2022. See Klara Kemp-Welch’s account of informal connections during the late 1960s and 1970s primarily in Eastern Europe, with some focus on Russian-Czech exchanges: Kemp-Welch, Networking the Bloc: Experimental Art in Eastern Europe, 1965–1981 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2019). See also Miglena Nikolchina’s analysis of the forum of the oral seminar as it provided a powerful format for exchange during the long collapse: Nikolchina, Lost Unicorns of the Velvet Revolution: Heterotopias of the Seminar (New York: Fordham University Press, 2013).

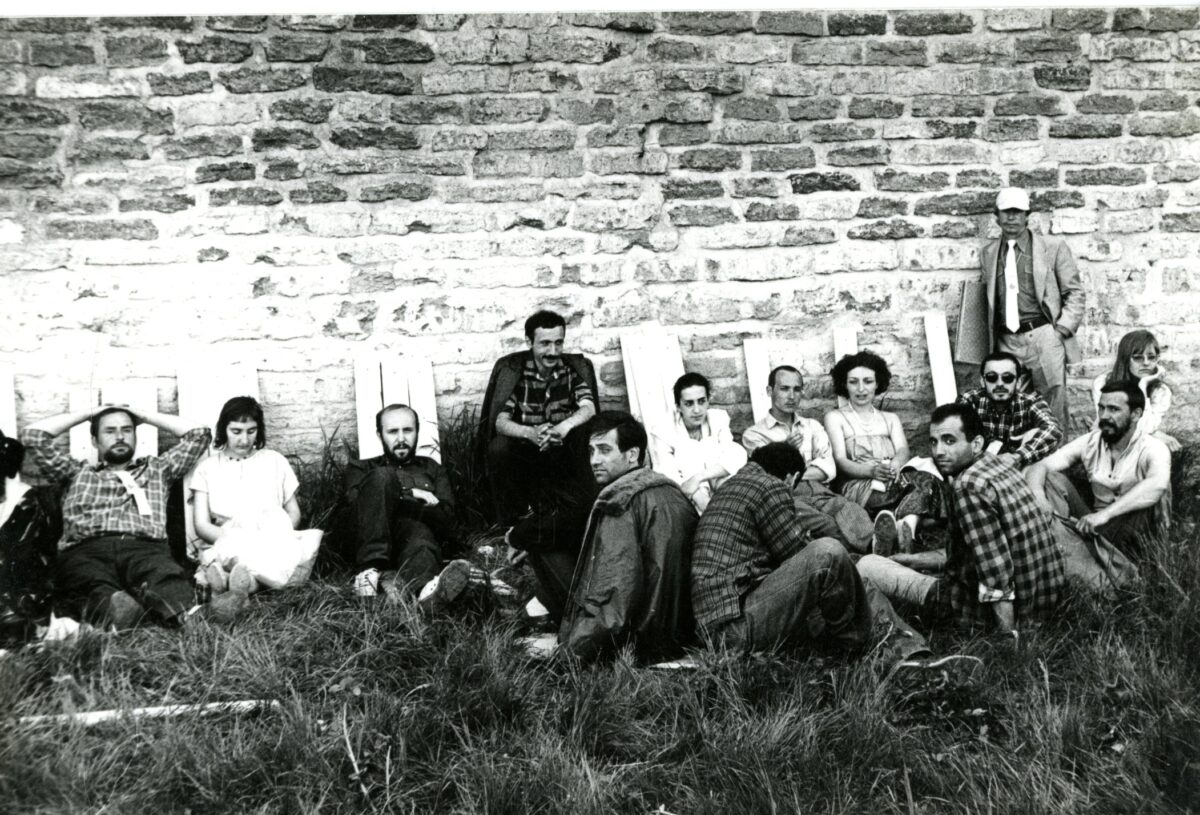

Narva-88 also marks the heyday of the unofficial art collective and of performance art broadly speaking—blending installation environments and performative actions carried out by individual and collective bodies. The festival was attended by members of the Georgian Marjanishvilebi, the Armenian Third Floor group, several Belarusian groups—Forma, Kvadrat (the Square), and Belarusian Climate—and the infamous Russian Mitkis. Artists exhibiting at Narva-88 who went on to have solo careers in the mid-1990s in installation, performance, and video art in addition to Shvelidze and Kasmalieva include Mamuka Japharidze (born 1962), Niko Tsetskhladze (born 1959), Mamuka Tsetskhladze (born 1962), Oleg Timchenko (born 1957), Gia Rigvava (born 1956), Koka Ramishvili (born 1956), and Karlo Kacharava (1964–1994) from Georgia; Igor Kashkurevich (Ihar Kashkurevich, born 1957) and Ludmila Rusava (1954–2010) from Belarus; Arman Grigorian (born 1960) from Armenia; and Zhilkichi Zhakypov (born 1957) from Kyrgzstan, among others. Narva-88 also marked a pivotal moment in the development of improvisational performance, installation, and public art across the Soviet Union, building on movements staged in private apartments and squats or outside of the urban setting since the 1970s. Moreover, for the first time, it brought improvisational works manifest as collaborative actions orchestrated between collectives to an international public stage.

The organization of the official Soviet festival foregrounded the tension between waning attachments to the Soviet institutional form and the unofficial genres of installation and performance works staged there. While the festival organization in part reflected Kasmalieva’s personal connections to emerging unofficial collectives, the Estonian festival organizers also sent official invitations addressed to “national delegations”— the artist unions of the Kyrgyz, Georgian, Armenian, and Russian Soviet Socialist Republics (rather paradoxical given that many of the artists who attended were not affiliated with the official unions)—inviting them to a festival and two-day seminar on the problems of contemporary art. The festival program, held at Narva Castle, consisted of exhibitions and youth events. Lodging was provided for artists at the nearby youth summer camp – the Estonian International Youth Center—on the banks of the Baltic Sea. The cultural program for the festival included classical music concerts, rock concerts, literary readings, and a performance by the Estonian children’s choir. The seminar program included a series of lectures and discussions of problems in contemporary art and film screenings, including of the previously censored Andrei Rublev (1966) by Andrei Tarkovsky (1932–1986), signaling the increasing integration of unofficial culture into official forums during the late Soviet period.9All documents and video footage related to the Narva festival, unless otherwise noted, are held in the official archive of the Narva Museum in Estonia (hereafter NMA). The archive consists of three folders of collected materials: typeset schedules for seminars and festival events; a list of aims and directives; lists of attendees; official invitations to national artist delegations; newspaper articles about the events; still photographs of selected works, attendees, and events; and a film. Information about the aims and schedule of events can be found in the unnumbered collated papers labeled “Seminar: v ramkax prazdnika iskusstva—88. Narva, 20–30 May 1988 goda.”

Official documents outline the general aims and structure of the festival. They announce the creation of a local archive in Narva for the promotion of “peace, ecology, and culture,” reflecting Cold War environmental campaigns that began under Nikita Khrushchev and called for a turn away from Stalinist industrialization and toward the new ideological frameworks of “friendship, ecology, and peace.” Narva-88 is described as a prazdnik, or holiday, celebration, and festival, a sentiment echoed in the youth summer-camp setting. The goals listed for the seminar include “the development of the new structures of the festival to form the basis of a new tradition” such as “festival design” and a study of the urban and social infrastructure of the festival.10NMA.Many of the activities, including youth choir performances, rock concerts, and film screenings, drew directly from the traditional Soviet festival playbook as did the lodging and official invitations. The works created in the seminar, which were largely improvisational and incorporated found materials, were required to be exhibited and then to become part of the primary collection of a Narva museum of contemporary art. In this way, Narva-88 made the festival genre—the development of festival traditions and social infrastructure—foundational to the creation of a contemporary art scene. The festival environment, in turn, played a broader role in generating experimental performance aesthetics, exemplifying a shift to bring experimental art into public spaces.

From late 1986 through the summer of 1987, a wave of environmental protests and indigenous land rights movements sprang up in the Baltics, motivated by increased ecological concerns following the catastrophic Chernobyl disaster and a series of Soviet industrial projects that created an influx of Russian workers to the region that further heightened social and cultural tensions.11See Beissinger, Nationalist Mobilization and the Collapse of the Soviet State, 147–99. Against the backdrop of these dissident mobilizations for territorial and cultural sovereignty in the late 1980s across the republics, Narva staged works that resonated with signs of the imminent dissolution of the Soviet empire. The festival thus at once emphasized the politics of the cultural turn through spectacles of the Soviet “good-life”—promoting Soviet optimism and friendly multinational relations—and called for the aesthetic renovation of contemporary unofficial art movements that mediated local desires for ecological preservation and cultural autonomy. Ecology and wildness served conjointly as recurring themes, political symbols, and methods driving the experimental art at Narva. Belarusian Climate described their art as an attempt to “convey the wild (dikii) humidity” of late Soviet life in the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic. “Here, in this territory, it feels a little bit colder, then hotter—that is, everything is unbearable. A small thing becomes hypertrophied due to this wild humidity. There is no comfort here.”12Tania Arcimovich, “Art-gruppa ‘Belarusskii Klimat’: Mifopoetika perekhodnoi epokhi.” Originally published on Kalektar research platform, http://zbor.kalektar.org/14/. Manuscript provided by author. See also Tania Arcimovich, “’Freedom Cannot be Personal,’ or Art as a Restrictions Antithesis,” Minsk. Non-conformism of the 1980s (Minsk: Galiiafy, 2016). I am grateful to Sasha Razor and Aleksei Borisionok for for this material. The Georgian Marjanishvilebi also called themselves dikie, or the wild ones, in a parodic reversal of the imperial Russian Orientalist imaginary of the “wild Caucasus.”13This Orientalist framework is explored in Susan Layton, Russian Literature and Empire: Conquest of the Caucasus from Pushkin to Tolstoy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995); Harsha Ram, The Imperial Sublime: A Russian Poetics of Empire (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003); Katya Hokanson, Writing at Russia’s Borders (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008); and Leah Feldman, On the Threshold of Eurasia: Revolutionary Poetics in the Caucasus (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2018). For Kyrgyz artists Gulnara Kasmalieva and painter Zhilkichi Zhakypov, wildness also invoked a connection to nature. For their installation, they constructed an artificial garden at the Narva castle: an abstract composition of grass, stones, and plastic bags filled with water laid around a circle cut into the grass.14Yuri Igrusha (Jury Ihrusha), Prazdnik iskusstva, video, 18:21–18:56, held in the collection at the NMA.

While the work was hailed as a “synthesis of the national and international,” as if echoing Soviet internationalist propaganda, Kasmalieva instead described her interest in the textures of the installation, which like Sick Bus, highlighted the sensuous and environmental dimensions of the work.15Ziterova, “Prazdnik Iskusstva v Narve,” Sovetskaia Estoniia 158, no. 8 (1988): 2; Gulnara Kasmalieva, interview by Leah Feldman, July 19, 2022. For Kasmalieva, it illuminated the play of light reflecting off the water-filled bags and the contrast between the texture of the grass from the field and the stark geometric imprint of the cut circle that became visible when viewed from the castle above.16Gulnara Kasmalieva, interview by Leah Feldman. Both the festival and natural environment at Narva shaped the sensuous experience of the encounter with these installations. Kasmalieva’s recuperation of the artifice of the “natural” installation, in turn, playfully subverted a Soviet image of an “authentic” Kyrgyz national art. Poised between a critique of Soviet industrialization and Orientalist imaginaries of the non-Russian republics, for the Belarusian, Georgian, and Kyrgyz artists, the wilds came to reclaim ecology as a site for unofficial art-making, cultural and ecological autonomy and the basis for a collaborative improvisational method.

One of the most captivating documentations of the festival wilds is recorded in a video of the event filmed by Belarusian filmmaker Yuri Igrusha (Jury Ihrusha, born 1963) and collected at the Narva Museum archive.17Yuri Igrusha (Jury Ihrusha), Prazdnik iskusstva, video, 2:2:32, NMA. The structure of the video itself echoes the official festival framework, with each “chapter” attributed to a national artist delegation. However, though the narrative follows this formal arrangement, Igrusha’s videography features experimental documentary film techniques, including sometimes jarring handheld camerawork, exaggerated close-ups, lengthy pan shots, and montage. Igrusha’s cinematography also captures the improvisational performances staged on the Baltic Sea beach next to the camp where the artists resided, a thirty-minute bus ride from the exhibition at the Narva Castle.

The montage sequence begins with a close-up of a JVC television, which zooms out to a wide-angle shot that situates the TV on the Baltic Sea beach.18Igrusha (Ihrusha), Prazdnik iskusstva, 1:19:26.The JVC television was one of the iconic foreign imports that gained popularity in the Soviet Union in the 1980s. Its image here also prefigures the promotion of the medium of video art by “post-Soviet” development initiatives like Soros in the late 1990s through early 2000s. Belarusian artist Igor Kashkurevich (Ihar Kashkurevich), dressed in a black scarf painted with white crosses—a garment designed by Ludmila Rusava to evoke the Black Square (1915) by avant-garde painter Kazimir Malevich (1878–1935)—walks along the beach to greet the camera.19Igrusha (Ihrusha), Prazdnik iskusstva, 1:20:05.

The camera then cuts to a shot of three members of Belarusian Climate, who are buried feet-first in the sand, their naked upper torsos emerging from the sand—suspended in classical poses as if sculptures—as the fog from the sea rolls across their bodies. 20Igrusha (Ihrusha), Prazdnik iskusstva, 1:21:05–1:21:07.

The next shot is an image of their bodies planted face down in the sand, and it cuts to a sand sculpture made by Kashkurevich of a woman’s body stretched across the beach. The camera pans—tracing the sand sculpture’s form against the evening light—and then cuts to morning, when it has been severed by a tractore. 21Igrusha (Ihrusha), Prazdnik iskusstva, 1:21:56–1:23:50.

Every evening, a military tractor patrolled the border, policing movement across European waters by night. Both the sand figure and the performance actions made by the artists’ bodies are staged on the tractor lines, which mark both the policing of the political border and the temporal transition from day to night. Belarusian Climate walks into the sea, naked, holding pododeialniki,or Soviet-made duvet covers, notable for their design, which features a rhomboidal hole in the center.22Igrusha (Ihrusha), Prazdnik iskusstva, 1:36:25–1:37.

The rhomboidal hole seems at once to conjure a contorted vision of Malevich’s canonical avant-garde revolutionary form and to evoke the material tradition of Soviet manufacturing. The objects—the JCV television and pododeialniki—thus render cotemporaneous the global import and consumer product as they expose the artists’ bodies suspended in a complex set of desires: for a Soviet festival “good-life,” for global consumer products, and for the legibility of experimental performance on an international stage.

These artworks improvised visions of wilds that captured the dynamism of this transitional space and time, engaging found materials and collaborative performances that illuminated shifting border zones on the eve of dissolution. The natural landscape (the sand and sea), the liminal spaces of the fortress and beach, the margins of the Soviet empire, and the sociopolitical scene at this site of border policing across which allegedly only consumer products could circulate shaped the artworks around and through the political and social collapse. As one of the last Soviet festivals, Narva-88 not only challenges the finality of “post-,” its homogeneous portrait of the end of history, and the whitewashing of the Soviet empire. In its exploration of this transitional space and time—on this border zone at the eve of collapse—Narva also exposes how artists from Tbilisi, Minsk, Bishkek, and beyond drew on performance art to experiment with their own repertoires of aesthetic and political gesture. Narva-88 conjured the waning imaginary of Soviet-national art in the process of its unraveling, and in so doing, generated political and aesthetic openings—rhomboidal or otherwise—for the unruly collectivities that must succeed “post-.”

- 1Throughout this essay, I use the term “unofficial artists” to refer to a generation of artists practicing experimental performance, installation, and street art outside of official Soviet institutional forums. However, many of the artists whose work I discuss here received training across the republics or participated in Soviet-wide artistic exchanges through official funding channels.

- 2For more on nationalist mobilization amid the collapse, see Mark R. Beissinger, Nationalist Mobilization and the Collapse of the Soviet State (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 47–102.

- 3Curator Ninel Ziterova—with the department of culture of Narva Gorispolkom (the city’s executive committee) of the Estonian SSR—was one of the official organizers of the festival. This quotation is from Ziterova, “Prazdnik Iskusstva v Narve,” Sovetskaia Estoniia 158, no. 8 (1988): 2. Translation mine.

- 4The name “Marjanishvilebi” was derived from the group’s clandestine studio in the Marjanishvili Theatre. See Vija Skangale, “An Underground Bridge to Georgian Collectiveness: Finding a Tribe through Collective Trauma,” post: notes on art in a global context, posted July 15, 2022, https://post.moma.org/an-underground-bridge-to-georgian-collectiveness-finding-a-tribe-through-collective-trauma/. In the 1970s abstract artists such as Avto Varazi (Georgian SSR) straddled official and unofficial spheres as they were occasionally paid to show work in the National Gallery (one of the only official art spaces at the time) while at the same time helped to organize apartment exhibitions.

- 5The installation at Narva was followed the same year by group exhibitions at the Galerie Eigen + Art in Leipzig and the Fransuaza Friedrich Gallery in Cologne and, in 1989, at the Black and White Gallery in Budapest and in the exhibition—Georgian Avant-Garde 80s— at the State Ethnographic Museum in Leningrad.

- 6See Sotheby’s, Russian Avant-Garde and Soviet Contemporary Art, sale cat., Moscow, July 7, 1988.

- 7See Francis Fukuyama, “The End of History?” National Interest, no. 16 (Summer 1989): 3–18.

- 8Gulnara Kasmalieva, interview by Leah Feldman, July 19, 2022. See Klara Kemp-Welch’s account of informal connections during the late 1960s and 1970s primarily in Eastern Europe, with some focus on Russian-Czech exchanges: Kemp-Welch, Networking the Bloc: Experimental Art in Eastern Europe, 1965–1981 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2019). See also Miglena Nikolchina’s analysis of the forum of the oral seminar as it provided a powerful format for exchange during the long collapse: Nikolchina, Lost Unicorns of the Velvet Revolution: Heterotopias of the Seminar (New York: Fordham University Press, 2013).

- 9All documents and video footage related to the Narva festival, unless otherwise noted, are held in the official archive of the Narva Museum in Estonia (hereafter NMA). The archive consists of three folders of collected materials: typeset schedules for seminars and festival events; a list of aims and directives; lists of attendees; official invitations to national artist delegations; newspaper articles about the events; still photographs of selected works, attendees, and events; and a film. Information about the aims and schedule of events can be found in the unnumbered collated papers labeled “Seminar: v ramkax prazdnika iskusstva—88. Narva, 20–30 May 1988 goda.”

- 10NMA.

- 11See Beissinger, Nationalist Mobilization and the Collapse of the Soviet State, 147–99.

- 12Tania Arcimovich, “Art-gruppa ‘Belarusskii Klimat’: Mifopoetika perekhodnoi epokhi.” Originally published on Kalektar research platform, http://zbor.kalektar.org/14/. Manuscript provided by author. See also Tania Arcimovich, “’Freedom Cannot be Personal,’ or Art as a Restrictions Antithesis,” Minsk. Non-conformism of the 1980s (Minsk: Galiiafy, 2016). I am grateful to Sasha Razor and Aleksei Borisionok for for this material.

- 13This Orientalist framework is explored in Susan Layton, Russian Literature and Empire: Conquest of the Caucasus from Pushkin to Tolstoy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995); Harsha Ram, The Imperial Sublime: A Russian Poetics of Empire (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003); Katya Hokanson, Writing at Russia’s Borders (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008); and Leah Feldman, On the Threshold of Eurasia: Revolutionary Poetics in the Caucasus (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2018).

- 14Yuri Igrusha (Jury Ihrusha), Prazdnik iskusstva, video, 18:21–18:56, held in the collection at the NMA.

- 15Ziterova, “Prazdnik Iskusstva v Narve,” Sovetskaia Estoniia 158, no. 8 (1988): 2; Gulnara Kasmalieva, interview by Leah Feldman, July 19, 2022.

- 16Gulnara Kasmalieva, interview by Leah Feldman.

- 17Yuri Igrusha (Jury Ihrusha), Prazdnik iskusstva, video, 2:2:32, NMA.

- 18Igrusha (Ihrusha), Prazdnik iskusstva, 1:19:26.

- 19Igrusha (Ihrusha), Prazdnik iskusstva, 1:20:05.

- 20Igrusha (Ihrusha), Prazdnik iskusstva, 1:21:05–1:21:07.

- 21Igrusha (Ihrusha), Prazdnik iskusstva, 1:21:56–1:23:50.

- 22Igrusha (Ihrusha), Prazdnik iskusstva, 1:36:25–1:37.