Sharon Chin is an artist and activist based in Port Dickson, Malaysia. For Chin, the two practices are related, intertwined. Their demands and their burdens, however, are different, and so is the agency that informs and shapes them. Chin talks about how she has learned to cultivate a productive relationship between these two pursuits across two decades. Leaning into considerations of address, the artist shares her thoughts about the locations and locutions of the political in her work. This edited transcript comes out of two interviews conducted with the artist over email and video call in September 2024.

Carlos Quijon, Jr.: A typical entry point to the political in art is representation. I am interested in how you conceptualize the political and ideas of representation in relation to your practice, particularly in terms of your chosen materials and modalities. For one, this question relates to how you are also very embedded in activism, and most of your works use the forms and materialities of activist paraphernalia—banners, placards, etc. These are forms that are not necessarily made to last. Usually they are made from whatever materials are available and intended to be site-specific and very agile. For the other, there is the notion of address. We can think about the place of Port Dickson in Malaysia in your work, which is, in a sense, a hyperlocal site. What do you think about that in relation to, for example, the legibility of the political in your work? This question of address further opens up to the category of contemporary art. How do you reconcile your practice’s specificity of address with the wider circulation and citations of global contemporary art? Is this something that you also try to speak to in your work?

Sharon Chin: One of the features of doing activism here [in Port Dickson]—extremely local political action—is that so much depends on being around. The more I participate in the art world, the more I’m in a state of hypermobility that puts me at odds with staying local, or as I prefer to say it, being around. I’m away for a time, and I’ll miss things—that’s normal. But if it keeps happening, then the relationships that have built up from me being around start to adjust to the reality of my intermittent presence. And it’s not just neighbors and townspeople, it’s the land. The animals and plants, the mangrove trees, the rocks on the beaches . . . they forget my name, they lose my number.

This sounds like a one-way ticket to burnout at both ends. But spending time on the land has helped me understand that endurance can look less like individual struggle and more like collective ongoingness. When I saw the first green shoots in a mangrove forest devastated by an oil spill, I knew that crabs and snails had probably come back under the mud and were doing their thing. At some point, if we’re lucky, the feedback loops of mutually engaged agents in an ecosystem reach a stage where they take on a life of their own. I try to remember that and focus my activism on multiplying relations between neighbors, surrounding neighborhoods, local authorities, and refinery executives. Broadcasting online is not central at all to the strategy, but it is an important tool to have. The goal is to create social connections that are dense enough to produce emergent outcomes—and to reduce reliance on any single agent.

What I call “going on the land” is just spending time in the landscape that I call home. Being with the land, hiking, whatever. I’ll admit, in the beginning (a few years ago), I would go with a proposal or grant deadline chasing my heels, and look to the land to provide—I don’t know—content or insight or something I could use. But in recent years, I’m not searching for anything when I’m out on the land. It’s more like a leisurely day with a favorite person—brunch, a second coffee, evening drinks. That kind of pleasurable intimacy and companionship, always finding something new in their dear, familiar face. A relationship defined by long and stimulating ongoingness.

Then there’s the oil refinery next door. That’s an ongoing relationship too. It was established by Shell in the 1960s and taken over by a Chinese multinational in 2018. The first few years of the new management were not bad—they engaged residents in good faith and actively tried to mitigate the pollution from the refinery. But that changed when the C-suite turned over, and the last three years have been like living next to Mordor. I need to be around all the time, otherwise we lose momentum in the neighborhood organizing—a fact that’s at odds with the mobility and visibility requirements of participating in the art world.

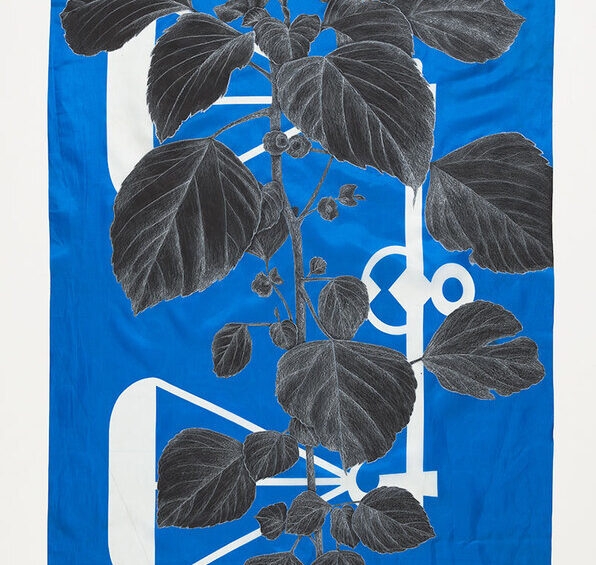

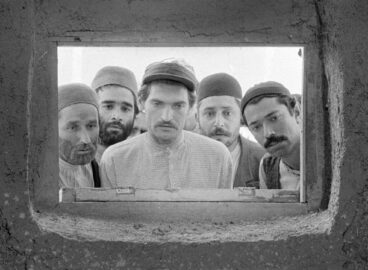

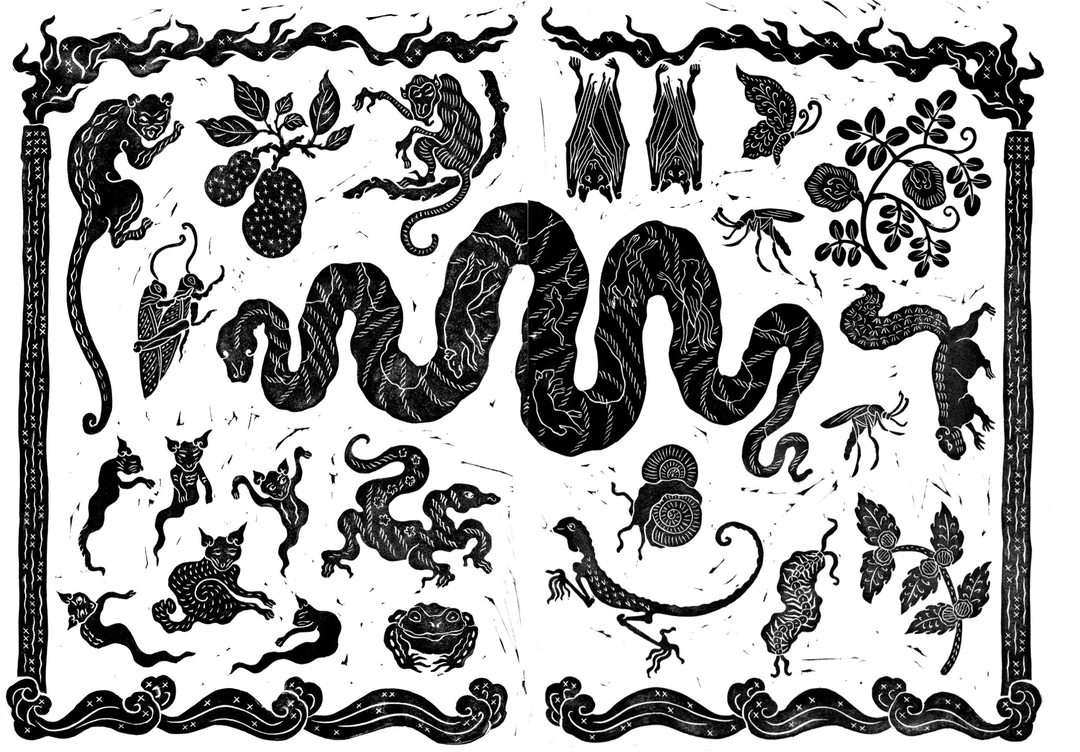

A similar ongoingness has been playing out in my practice since 2018, when Creatures of Near Kingdoms came out. It’s a book of short stories about fantastic animals and plants, set in Southeast Asia. My partner Zedeck Siew wrote the stories, and I made a series of linocuts and repeating patterns to illustrate each one (fig. 1). I’ve iterated some of the animal forms in the book into a number of projects over the years: enlarging them into placards for a climate protest in Kuala Lumpur (2019; figs. 2–5) and photographing them as shadow puppets lit by the refinery flare for Creatures on the Move (2022–24; figs. 6–8). An upcoming show in 2026 will bring me closer to realizing my vision of a shadow-puppet play, but it will also be about animals disappearing from the scene, leaving humans alone on the stage we created and in the spotlight we’re so unwilling to share. Where have they gone? I want to find out—I will follow them.

To your point about how these conditions have shaped the formal aspects of my work, I’d say I’m conscious of playing with a certain lack of polish in presentation. I am familiar with the grammar of the gallery or museum space. I’m not sure these are necessarily political choices given the context, but they are certainly aesthetic ones. For example, wheat-pasting poster images directly to the gallery walls for Creatures on the Move, as opposed to using light boxes or getting wall stickers professionally installed (figs. 9, 10). The technique is messy and laborious and finicky enough that I have to be on-site to do it myself (with assistants). But the glitches and wrinkles left behind exude the warmth of humans working in space and time, which I believe can be perceived by the person looking. How much of this is just compensating for my lack of technical ability or resources to create high-definition finishes? It doesn’t matter. I’m an artist as well as an activist, and how good or bad my politics are is not a stand-in for the formal choices I make in a gallery space. It’s probably more important to remember that the reverse is also true.

CQJr: My next question is a bit more self-reflexive. I am wondering if there’s some anxiety about these forms being cannibalized by the art world. In relation to, for example, more performative, ephemeral, temporary forms and how these kinds of materials and forms have been co-opted by the contemporary art world into mere spectacle or contemporary currency. I was wondering if you have this anxiety?

These kinds of forms can easily be co-opted by contemporary art into abstract values of specificity or timeliness. Or if there’s no anxiety, I am wondering if you’ve been thinking about ways to prevent this co-optation. I think, off the top of my head, that your idea of “anti-polish” is something like that. Do you have these kinds of strategies for how to participate in the contemporary art world without having the political edge of such forms blunted by it?

SC: In contemporary art spaces, staging—what is allowed to be visible—is everything. I am constantly aware of that. In many ways people can only perceive what is put in front of them. In terms of the reality of living next to an oil refinery, I’m not interested in representing my activism work in a gallery space because 1) I have yet to be moved by seeing a spreadsheet in a museum, and 2) it doesn’t help the activism.

Although I have been tempted sometimes to do that because there’s a legitimacy to all that documentation, I’m averse to most archive-based artworks in a gallery setting, where there are vitrines, diagrams, files of documents to dig through, books on a shelf, etc. And I understand it’s a whole museological thing. What’s interesting is that evidence-gathering has been crucial in our neighborhood’s struggle against refinery pollution. There’s so much data collection and building paper trails for every stage of engagement. Then the material has to be translated, i.e., made legible, to various agents. In fact, CCTV footage of the refinery’s flare stack has done the most so far to convince both the public and the authorities of the harm that’s being done to us by industrial emissions (figs. 11–12, 19–23).

But when it comes to an exhibition, I’m not thinking about that kind of legibility at all. I’m concerned about how these empirical data are translated into questions of form, of space. I’m concerned with what’s going to seduce the person who’s looking, because that’s why I look at art: to be entranced and transported into the heart of something.

The anxiety about being co-opted, I feel . . . no, I don’t. Maybe I used to, but these days, there’s a confidence in being able to step into different spaces and contexts. It’s funny—I used to have more anxiety about it when I made art about national politics, like Weeds/Rumpai (2013–15), a series of weeds painted on political party flags collected during election time (figs. 13–14), or Mandi Bunga/Flower Bath (2013), a performance inspired by the Bersih movement for clean and fair elections, in which I had a hundred people take a flower bath with me in public (figs. 15–18).

I think doing activism at the local level has made me more confident about stepping into and addressing the particularities of any given space. So if we’re in the contemporary art space, I’m in control of what goes in, what is staged, and importantly, what is refused. Sometimes it helps to think about being like a river (although I find it vaguely obnoxious or cringeworthy—who do I think I am, Bruce Lee?), because that means there’s no place I won’t go, but also, I’m just passing through; I won’t be trapped, and there’s nothing to fear.

Whatever the work or project is, it’s made to be carried into different contexts. There is a lightness and contingency built into the form that helps it catch whatever current is available. All this stuff needs to find its way back, too, to the place that gave it meaning—that’s its momentum. That circulation is very important, because it’s how you don’t get trapped by prestige or authority or the need to impress. The gallery or institution is not where things end. It shouldn’t end there. It’s just another stop.

CQJr: I think this also speaks to how you foreground ideas of distribution and circulation and their relationship to the political. I feel like the one thing about forms, particularly “activist forms,” like the effigy, the agitprop, the zines, is that all of them that are easy to produce and distribute, easy to let go of, easy to shed off, easy to keep. So, I think that’s also something interesting about your practice, how that formal genealogy also informs or is thought through your works. There is a keen attentiveness to this across what you do.

My last question is in relation to the categories. I feel like the categories always matter because with the categories comes currency and visibility. What do you think about art and activism? How do you see, in your practice in particular, the relationship between art and activism? And I want to dovetail this question to what you mentioned before as the seduction of form.

I feel like that was something interesting when we were doing the project with Ilham Gallery in Malaysia. Of course your work there was about Port Dickson and the effects of the refinery on the community, but you created wayang puppets of animals found in and around Port Dickson. This was the translation that you mentioned earlier, and it was so evident in that project. You don’t lose sight of the politics of the refinery, but it’s not like your activist persona will be the same as your artist figure. I am wondering if you can talk more about the relationship between art and activism—and how the forms are the ones in a way mediating the relationship for you.

SC: I think this can be clarified with that river metaphor. Lately I have started to ask myself, “Can the neighborhood speak to the national or international, and what does it have to say?” But then there’s the other question: Can the national or international artist speak to the neighborhood?

When I lived in Kuala Lumpur, the capital, I felt comfortable about speaking on what I perceived to be national issues, translated through an intensely personal and subjective lens. My works were addressed to an imaginary national audience. But the thing about moving to Port Dickson and becoming a local is that the address turns around, and I am confronted with the question of how to speak to the people here. Now the river metaphor turns into a challenge to live up to: Can you go everywhere, in all directions? Back and forth from the neighborhood to the national and from the national to the neighborhood. So we’re just circulating things constantly: forms, ideas; translating, carrying something from there to here.

I think what artists and activists share is a spirit or a will to intervene in reality. You’re awake to the world and all its forms of address to you. You’re picking up those calls, baby. Otherwise, where will the art come from—or the frankly stupid conviction required to make things better for life on earth?