In this text, Dorota Jagoda Michalska writes about Erna Rosenstein (1913–2004), a Jewish Polish postwar artist. Until now, Rosenstein’s work has been situated among the very few examples of Surrealist work in socialist Poland. Michalska opens up a transnational perspective, inviting us to look at the artist’s oeuvre through the lens of global surrealisms, connecting her articulations of Holocaust trauma with the work of artists who have dealt with slavery, genocide, exile, and colonial dispossession.

Against a black and lustrous background, a silvery landscape painted with elegant and delicate lines emerges. An aural simmering envelops what looks like the gentle slope of a mountain in the far-off distance. Several fractured lightnings irradiate from the mountain’s peak, cutting through the black background. Erna Rosenstein’s enigmatic painting Palace of Lightnings (Pałac błyskawic, 1989) has rarely been the focus of critical reflection, because it slips through the main theoretical categories used to describe the artist’s oeuvre. Current scholarship sees her work as an articulation of Holocaust trauma, situating it within the field of postwar modern art in Eastern Europe.1See Dorota Jarecka, Surrealizm, realizm, marksizm: Sztuka i lewica komunistyczna w Polsce w latach, 1944–1948 (Warsaw: Instytut Badań Literackich PAN, 2021). Scholars also underscore that her paintings are among the very few examples of Surrealism in socialist Poland.2See Dorota Jarecka and Barbara Piwowarska, eds., Erna Rosenstein: Mogę powtarzać tylko nieświadomie (Warsaw: Fundacja Galerii Foksal, 2014). However, her complex artistic practice benefits from a more transnational reflection, one that positions her work not only in the context of her Jewish identity and Polish history but also against a broader background of global experiences of Surrealism.

Present readings of Rosenstein’s practice see her work as inexorably linked to her biography. The artist was born in 1913 in Lviv (currently western Ukraine) to an upper-class Jewish family. While her parents acknowledged their ethnic background, they opted for full assimilation into Polish society. Paradoxically, while the artist herself did not consider her ethnic identity paramount, during the Nazi occupation of Eastern Europe, it was exactly her family’s Jewish background that brought tragedy upon them. In their escape from Warsaw in 1942, they were betrayed by a Polish shmaltsovnik (slang for a person who blackmailed Jews during the Nazi occupation), who brutally murdered the artist’s parents.

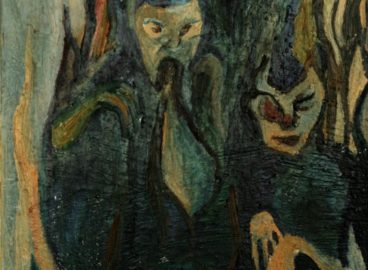

Miraculously, Rosenstein escaped and managed to survive. Among her most famous works is Screens (Ekrany) from 1951, which has been the central subject of most of the critical writings about Rosenstein. This violently traumatic painting portrays the decapitated figures of the artist’s parents playing ball with their cutoff heads. The work immediately makes us realize just how deeply Rosenstein’s work is rooted in the long history of the difficult cohabitation of Poles and Jews, which reached its tragic zenith during World War II.

While acknowledging the fundamental importance of this historical context, my text proposes a different inroad into Rosenstein’s practice. My aim is to situate her paintings in a broader, international context, one shaped by global histories of coloniality, dispossession, and racial necropolitics. It is for this reason that I want to place Rosenstein’s work within the framework of global histories of the Surrealist avant-garde as outlined in the 2021–22 exhibition Surrealism Beyond Borders, which included Screens.3Surrealism Beyond Borders, curated by Stephanie D’Alessandro and Matthew Gale, was held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (2021–22) and Tate Modern in London (2022). While Rosenstein’s work is often categorized as Surrealist within the framework of Polish art history, a comparative perspective opens up new readings of her practice, ones that challenge current narrations on the artist’s works.

Post-Genocidal Ecologies

In 1950, decolonial writer, thinker, and activist Aimé Césaire published the groundbreaking essay “Discourse on Colonialism,”in which he famously claims that there are profound and direct genealogical ties between fascism and the European colonial project. Césaire maintains that European colonies were an experimental ground for Nazism, especially the war and genocide waged upon the Herero and Nama people in Namibia.4Aimé Césaire, Discourse on Colonialism, trans. Joan Pinkham(1955; New York: Monthly Review Press, 2000), 16-21. Seen in this light, fascism was not merely a tragic exception in European history, but rather quite the opposite; in fact, it was a logical continuation of earlier historical processes and political formations. Nowadays, Césaire’s text is seen as crucial, because it traces fundamental historical parallels between the Holocaust and the experiences of slavery, genocide, exile, and colonial dispossession.5See Michael Rothberg, Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009), 5-25.

The historical parallels drawn by Césaire shed new light on some of Rosenstein’s paintings. For many years, I have been deeply fascinated by a number of her less well-known works, in particular, those that portray a complex landscape dominated by dark, lush, and impenetrable vegetation. The painting It Is Growing (Rośnie, 1965) presents a florid and vibrant ecological system of hybrid, organic forms undergoing constant transformation.

Another work—the more somber No Man’s Land (Ziemia Niczyja, 1964)—portrays a similar organic landscape; however, instead of brimming with greenery, it confronts us with dark, swirling layers of gray, which sit heavily on the painting’s surface. Both works can be seen as articulations of a post-genocidal landscape marked by fleeting echoes, decaying remains, and spectral presences. Indeed, Rosenstein’s organic ecosystems are expressions of an almost forensic artistic sensibility alert to the smallest and often non-visible traces of the genocide perpetrated by Nazism in Eastern Europe.6Andrzej Juchniewicz, “‘Ziemia otworzy usta’: O wyobraźni forensycznej Erny Rosenstein,” Narracje O Zagładzie, no. 5 (2019): 149–75, https://doi.org/10.31261/NoZ.2019.05.08.

As I looked at Rosenstein’s traumatic visions of nature, I was reminded of Jungle (La Jungla, 1943), which waspainted by Cuban artist Wifredo Lam (1902–1982) amid World War II. This painting is, nowadays, considered a fundamental decolonial work reflecting the diasporic identities of the Caribbean.7See Genevieve Hyacinthe, Radical Virtuosity: Ana Mendieta and the Black Atlantic (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2019), 8-29. More specifically, it is an attempt to articulate the postcolonial status of the Caribbean ecosystem marked by colonial violence, extortionists policies, racial fantasies, and slave labor. In 1951, Guyanese writer and decolonial thinker Martin Carter (1927–1997) expressed a similar sentiment in his poem “Listening to the Land”: “I bent down / listening to the land / but all I heard was tongueless whispering . . . as if some buried slave wanted to speak again.”8Stewart Brown and Ian MacDonald, eds., Poems by Martin Carter (Oxford: Macmillan Caribbean, 2006), 43. Lam’s Jungle and Carter’s poem closely resonate with Rosenstein’s paintings of post-genocidal nature, revealing a profound kinship between postcolonial landscapes marked by the histories of slavery and the Polish ecosystem in the aftermath of the Holocaust.

The Alchemy of Gender

Recent years have marked a resurgent interest in underrepresented women artists associated with Surrealism. Of special importance in this context is the rediscovery of women artists outside the Western canon, such as Egyptian painter and feminist activist Inji Efflatoun (1924–1989), Brazilian sculptor Maria Martins (1984–1973), and Czech painter and illustrator Toyen (1902–1980). How can Rosenstein be set against this expanded backdrop of Surrealism? Akin to numerous Polish women artists in the 1960s and 1970s, the Jewish-Polish artist never considered her work in feminist terms; rather, she insisted upon the universal dimension of her practice. However, a reframing of her works within global histories of Surrealism helps us to approach this question from a slightly different perspective.

Throughout her life, Rosenstein maintained a keen interest in alchemy. The language of alchemical practices, founded on such concepts as transformation, distillation, and sublimation, seems particularly well suited for describing the dynamic and ephemeral nature of her paintings. Her works often portray nebulous, vaporized matter that seems just on the verge of either liquifying or evaporating. While researching Rosenstein’s practice, I remember being immediately struck by her painting The Burning of the Witch (Spalenie czarownicy) from 1966. This work confronts viewers with its sprawling, painterly surface of swirling patches of intense color: vibrant reds, fleshy pinks, and deep yellows. The fluidity of shapes seems to echo an ever-changing magmatic surface that, in turn, invokes uneasy images of intense heat and flames. In this piece, Rosenstein directly refers to the widespread phenomena of witch-hunting and public burnings that engulfed early modern Europe (including Eastern Europe) in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. As such, her painting offers a powerful image from the long history of violence toward women and their dispossession by both capitalism and colonialism.

Alchemical practices were also key references for other Surrealists, including British-born Leonora Carrington (1917–2011) and Spanish artist Remedios Varo (1908–1963). In the 1940s, both Carrington and Varo found themselves in exile in Mexico, having fled Europe, which was, at the time, engulfed by Nazism. Soon the two formed a close friendship based on their mutual keen interest in alchemy. Indeed, scholars unanimously underline the proto-feminist dimension of alchemical references in both their work.9See Tessel M. Bauduin, Victoria Ferentinou, Daniel Zamani, eds., Surrealism, Occultism and Politics: In Search of the Marvellous (London: Routledge, 2017), 75. This is particularly evident in the case of Carrington, who was also actively engaged in the women’s liberation movement in Mexico. This context allows us to perhaps approach from a slightly different angle the question of gender in Rosenstein’s works. Though the artist claimed not to be interested in feminism, her focus on alchemy reveals an interest in processes of identity formation that eschew fixed categories of normative gender practices and policies. By focusing on alchemical transmutations—conjunctions, separations, sublimations—she forges her own artistic language to give voice to an unfixed subjectivity that slips through the enforced normativity of the discourse. While such an artistic language might seem removed from the more canonical forms of feminism, alchemy may have offered Rosenstein an idiomatic way of articulating her creative position in the postwar Polish art sphere dominated by male artists.

The Night of the Soul

In 1947, a volume of poetry entitled Suryāl (Surreal) was published in Aleppo, Syria. The avant-garde poet Urkhan Muyassar (1911–1965) claimed that the collected poems sought to unearth the “mysterious moments” of human creativity and to liberate them from the imposed tyranny of everyday life and the brutality of logic.10Anneka Lenssen, Beautiful Agitation: Modern Painting and Politics in Syria (Oakland: University of Califronia Press, 2020), 45–46. The circle of artists active in Aleppo understood Surrealism as an artistic and spiritual project of reaching toward “what lies beyond reality.”11Lenssen, Beautiful Agitation, 46. Such an understanding is deeply indebted to Sufism and older mystic practices. A similar claim was made later, in 1995, by Syrian poet Adūnīs (Ali Ahmad Said / علي أحمد سعيد إسبر, born 1930) in his book of critical essays Sufism & Surrealism. Adūnīs insists that there are fundamental ties between Sufism—as a mystical practice of losing one’s subjectivity and ecstatically approaching God/Nothingness—and writings by Surrealists poets and writers such as Arthur Rimbaud (1854–1891) or André Breton (1896–1966).12Adūnīs, Sufism & Surrealism (2005; London: Saqi Books, 2016). Originally published in Arabic as al-Sufiyya wal surriyaliyya (Beirut: Dar al Squi, 1995).

These considerations open up a new perspective on several works by Rosenstein that so far have escaped critical attention. Pieces such as Evening (Wieczór, 1974) or Palace of Lightning (Pałac błyskawic, 1989) portray the delicate outlines of fantastic landscapes, frail architectural structures, and isolated human silhouettes cast against a deep and impenetrable black background. At first glance, these works might be seen as expressions of Rosenstein’s traumatic war experience. However, a different reading is possible. These paintings can also be understood as attempts to express what the Spanish mystic and poet St. John of the Cross calls the “dark night of the soul.”13St. John of the Cross, The Dark Night of the Soul by St. John of the Cross, trans. David Lewis (London: Thomas Baker, 1908). This moment marks a profound spiritual and existential crisis, but ultimately, it also leads to a mystic experience of illumination. This view offers a different perspective on the current psychoanalytical interpretations of Rosenstein’s work, which usually describe it as a sort of traumatic repetition—that is, a horror that recurs in her paintings.14See Jarecka and Piwowarska, Erna Rosenstein. A mystical perspective allows us to see the “dark night of the soul” not only as a traumatic moment, but also as the beginning of an inner transformation. It is important to emphasize that—to my knowledge—Rosenstein was not aware of either the Syrian surrealists or Adūnīs’s writings; however, we can still weave together these parallel artistic sensibilities to see how they reflect and dialogue with one other.

By bringing mysticism into contact with Rosenstein’s practice, we might discover a new reading of her painting Clearance (Prześwit, 1968). To understand this work, we must be aware of the historical context of its creation: Rosenstein painted the piece during the anti-Semitic campaign that was waged in Poland in 1968 and resulted in hundreds of thousands of Jews leaving the country. However, other interpretations are also possible. The painting depicts a turbulent landscape with swirling gusts of violent pink. The land is in upheaval, and this restlessness hints at the histories of violence and genocide deeply embedded within the Polish landscape. Rosenstein represents reality as dominated by turbulent, billowing matter that abounds in dramatic transformations, movement, and sudden flashes. At the center of the image, a massive explosion of light is taking place, with sharp beams of light cutting across the whole canvas. The piece captures the moment just before the break of dawn—a mystical experience of vitality and renewal.

(Global) Polish Art Histories

Erna Rosenstein’s work recently has been exhibited in several important international shows, marking a new wave of interest her work.15Currently, Erna Rosenstein’s estate is co-represented by Foksal Gallery Foundation and Hauser & Wirth. In 2021, Hauser & Wirth opened the solo exhibition Erna Rosenstein: Once Upon A Time, curated by Alison M. Gingeras, in New York. While older scholarship almost exclusively situates her practice within the field of postwar art in Poland, my text takes a different approach in that it considers the global implications of her practice. I believe that Rosenstein’s paintings allow us to see important historical parallels between the works of artists impacted by the Holocaust and those of artists facing the experience of slavery, genocide, exile, and colonial dispossession. Such a perspective is of paramount importance as it makes it possible to consider art practices from Eastern Europe in an expanded field, to see them as deeply shaped by global formations of coloniality and race. This line of thinking allows us to go beyond dominant narratives of national exceptionalism and to instead forge horizontal networks of solidarity and common political consciousness. Rosenstein’s practice—like the fractured lightnings she painted in 1989—point us toward these multiple directions, sudden illuminations, and affinities between what, at first glance, might seem to be very different realities.

- 1See Dorota Jarecka, Surrealizm, realizm, marksizm: Sztuka i lewica komunistyczna w Polsce w latach, 1944–1948 (Warsaw: Instytut Badań Literackich PAN, 2021).

- 2See Dorota Jarecka and Barbara Piwowarska, eds., Erna Rosenstein: Mogę powtarzać tylko nieświadomie (Warsaw: Fundacja Galerii Foksal, 2014).

- 3Surrealism Beyond Borders, curated by Stephanie D’Alessandro and Matthew Gale, was held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (2021–22) and Tate Modern in London (2022).

- 4Aimé Césaire, Discourse on Colonialism, trans. Joan Pinkham(1955; New York: Monthly Review Press, 2000), 16-21.

- 5See Michael Rothberg, Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009), 5-25.

- 6Andrzej Juchniewicz, “‘Ziemia otworzy usta’: O wyobraźni forensycznej Erny Rosenstein,” Narracje O Zagładzie, no. 5 (2019): 149–75, https://doi.org/10.31261/NoZ.2019.05.08.

- 7See Genevieve Hyacinthe, Radical Virtuosity: Ana Mendieta and the Black Atlantic (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2019), 8-29.

- 8Stewart Brown and Ian MacDonald, eds., Poems by Martin Carter (Oxford: Macmillan Caribbean, 2006), 43.

- 9See Tessel M. Bauduin, Victoria Ferentinou, Daniel Zamani, eds., Surrealism, Occultism and Politics: In Search of the Marvellous (London: Routledge, 2017), 75.

- 10Anneka Lenssen, Beautiful Agitation: Modern Painting and Politics in Syria (Oakland: University of Califronia Press, 2020), 45–46.

- 11Lenssen, Beautiful Agitation, 46.

- 12Adūnīs, Sufism & Surrealism (2005; London: Saqi Books, 2016). Originally published in Arabic as al-Sufiyya wal surriyaliyya (Beirut: Dar al Squi, 1995).

- 13St. John of the Cross, The Dark Night of the Soul by St. John of the Cross, trans. David Lewis (London: Thomas Baker, 1908).

- 14See Jarecka and Piwowarska, Erna Rosenstein.

- 15Currently, Erna Rosenstein’s estate is co-represented by Foksal Gallery Foundation and Hauser & Wirth. In 2021, Hauser & Wirth opened the solo exhibition Erna Rosenstein: Once Upon A Time, curated by Alison M. Gingeras, in New York.