Tone Yasunao has been embracing contradictions and challenging the limits of the possible since his days as a college student in Tokyo, when he performed in an antimusic ensemble that he named Group Ongaku (Group music). The group used unconventional instruments such as dishes and a vacuum cleaner in their improvised music. In his solo work, in pieces such as Geodesy, meticulously executed sets of instructions yield a curious mixture of tension, comedy, and boredom. And on the other side of his compositions comprised of maximally amplified sounds, such as his MP3 Deviation Series, lies a Chinese literary tradition dating to the sixth and fifth centuries B.C.

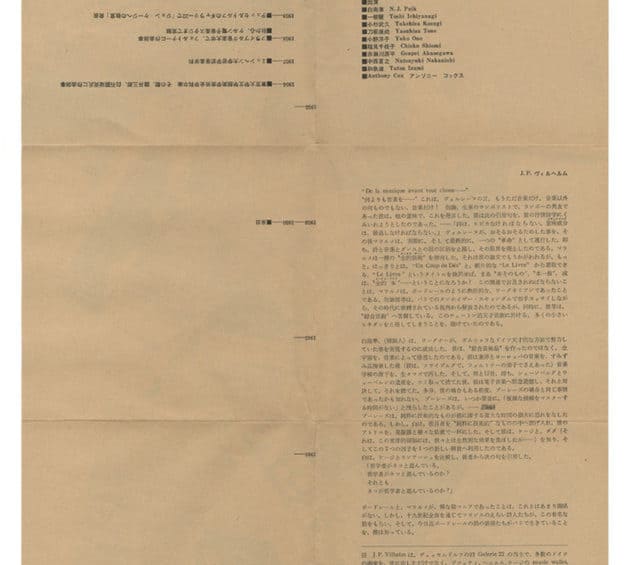

Over the years, as many of his iconoclastic peers from the postwar generation of Japanese artists have garnered prestigious titles and leadership roles in large cultural institutions, Tone has stayed put in the experimental art scene of downtown Manhattan, which has been his home since the 1970s. In his long career as a perpetual innovator and subversive figure in experimental music, he has worked with musicians, artists, and filmmakers such as Shiomi Mieko, Kosugi Takehisa, Nam June Paik, Yoko Ono, John Cage, George Maciunas, Kanesaka Kenji, and IImura Takahiko, among many, many, others.

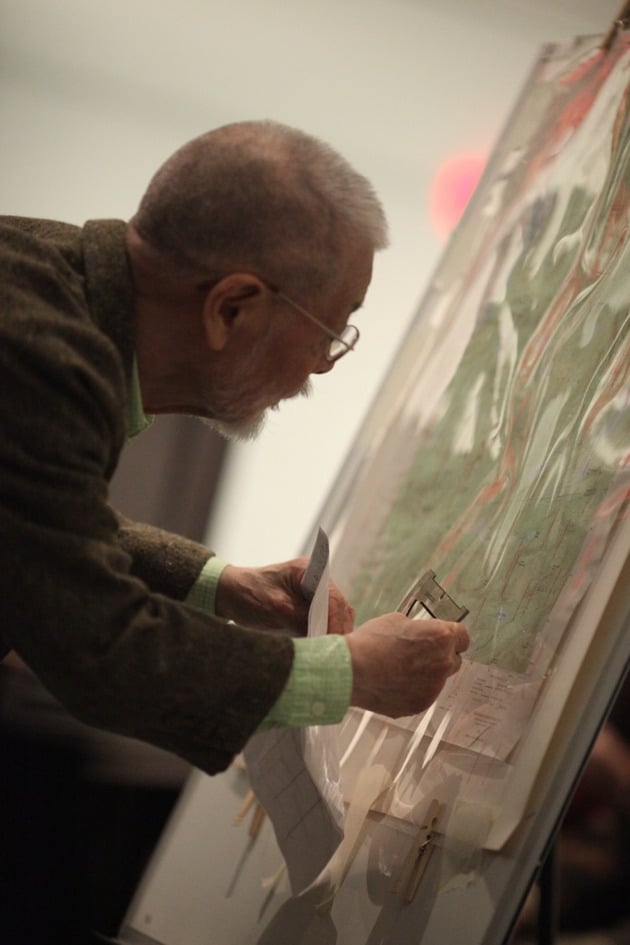

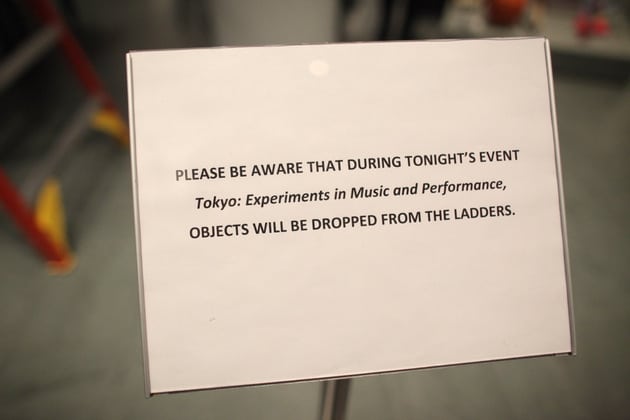

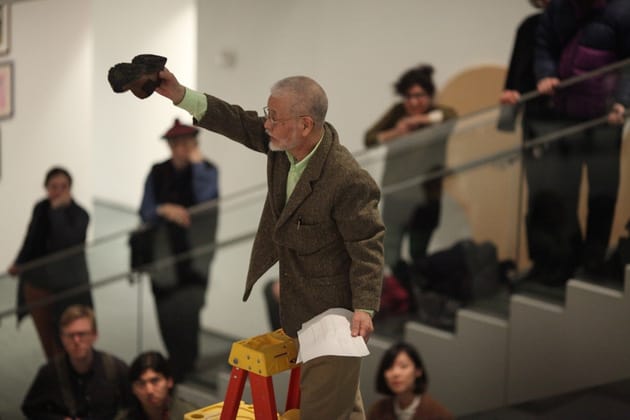

post is privileged to publish an extensive two-part interview with Tone, together with documentation from a concert of his works that was held at The Museum of Modern Art in January 2013 in the context of the exhibition Tokyo 1955–1970: A New Avant-Garde, and with material related to his output, since the 1960s, as a musician, artist, and critic. The first part of the interview, presented here, focuses on Tone’s early years as an experimental musician in Japan, his work with Group Ongaku, and his involvement with Fluxus in New York. The second part will focus on his work since the 1970s.

This interview took place in Tone Yasunao’s loft in Chinatown, NY, August 12, 2012.

“I picked up whatever was lying around and experimented with it.”

Miki Kaneda: Could you please say a few words about your student days and Group Ongaku?

Tone Yasunao: One thing I did in my student days that had an impact on my later activities was writing my thesis on Dada and Surrealism. Then, toward the end of the 1950s, some art students and I formed an improvisational music unit called Group Ongaku. Being a bit cerebral, I was initially planning to work on the theory side of things rather than actually performing. At some point, though, I got swept up in it and started playing music with them.

I started out on the sax. I hadn’t had any formal musical training, so at first I taught myself to play the sax with a manual. Then I gradually grew more ambitious and thought playing just a single instrument wasn’t enough. Koizumi Fumio, a professor who taught an ethnomusicology course at the art university, had all of these musical instruments from around the world, and I borrowed them one after another and performed with them.

After a while, though, that started to bore me, too, and I thought, “A musical instrument is an object, and it’s fundamentally no different from other objects.” I started picking up this and that object and using them to produce sounds. I might read aloud from a book, I might beat on a metal barrel or scrape on a washboard. I picked up whatever was lying around and experimented with it, making noise. It occurred to me that this was a form of automatism, and I persuaded the others to accept this interpretation. After that, everyone started talking about what we were doing in terms of automatism.

We formed the group in 1958, and in 1961 we played our first and last concert as Group Ongaku at the Sogetsu Art Center. Until then we had been playing in various places: in the Department of Musicology at the art school, of course, or in other unused classrooms there; at Mizuno Shuko’s house, or at the house of this guy, a friend of a friend, who made his own guitars. The guy was single, and making your own guitars costs a lot of money, so it was obvious the guy was well off. We kind of invited ourselves over to his place, and he said he wanted to improvise with us. Those are the kinds of places we played before doing the concert.

Around that time Shiomi Mieko (then known as Chieko) was giving piano lessons to Kaga Mariko’s older sister. Of course just sitting there practicing the piano is boring, so they got to talking, and Mieko mentioned that we were doing this Group Ongaku thing. It turned out that the sister was a classmate of my older brother’s at Meiji University, so there was a kind of double connection there. And the sister knew a music critic named Sakisaka Masahisa—ever heard of him? She offered to introduce us to him, and so we talked to him, and he said incredulously, “You guys perform without any audience?” We replied that what we did was automatism, and it wasn’t the kind of thing you perform in front of people. He said that was a wasted opportunity, and he would introduce us to the Sogetsu people, and we should most certainly perform there. We then met Igawa Kozo from Sogetsu, and he offered to let us perform without paying any rental fee for the hall.

That’s how we came to play our first concert at the Sogetsu Art Center. That is to say, our first concert by ourselves. We had performed earlier at a place called the Kuni Chiya Dance Institute, along with the dancers. We also played places like the Toshima Public Hall in Ikebukuro, along with friends of Kuni Chiya’s. It was different, though, because we were accompaniment for the dancers.

Kaneda: Where does the name Group Ongaku come from?

Tone: Kuni Chiya was involved with a group of young dance critics called Niju Seiki Buyo no Kai (20th-Century Dance Circle), and they were planning to run a feature in their journal about the connection between improvisation and dance, or some such theme. We were all invited to write a piece, as guest writers, but we didn’t have a name for our group. I suggested simply Ongaku (music), thinking about the literary journal Littérature that the Dadaists founded. That name was tongue-in-cheek, and I wanted ours to be, too. The Japanese word ongaku could be written with different characters, like「音が食う」, so that it means “sound eats,” or 「音が苦」, “sound is pain.” Since just calling it Ongaku would be confusing, we called it Group Ongaku, so that people would know what it was. That’s the origin of our name.

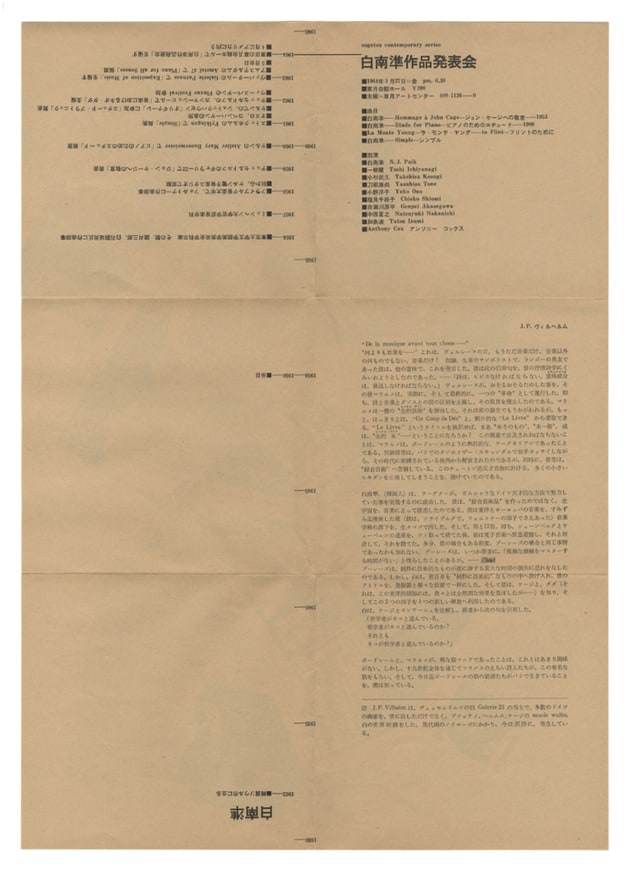

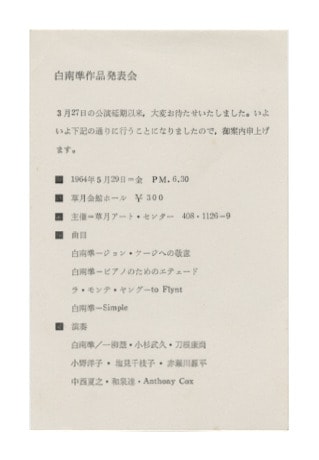

But our group split up after that first concert at the Sogetsu Art Center. What happened was, Kosugi Takehisa, Mizuno Shuko, and I got in an argument. It was Kosugi and I against Mizuno. Mizuno said what we were doing was not music. We said, “You’re a conservative reactionary unfit for our group.” That was the end of the group. However, I went on performing with Kosugi, and all the members later performed with me at my concert at Minami Gallery, along with Ichiyanagi Toshi and [Takahashi] Yuji.

Kaneda: Group Ongaku remains well known today. Was the public response to the group immediate?

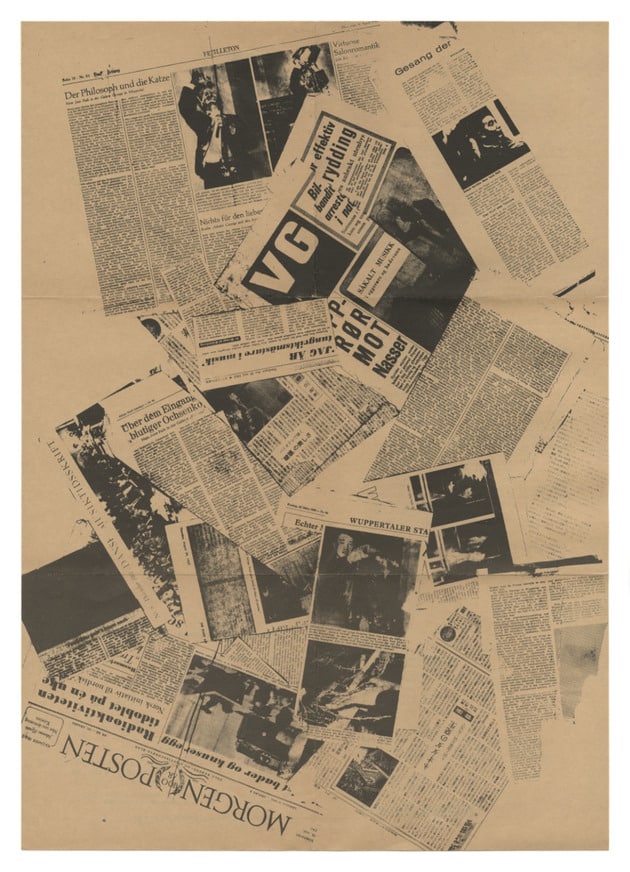

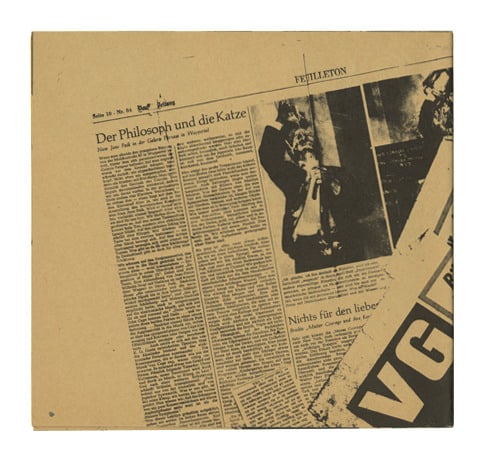

Tone: Well, that concert at the Sogetsu Art Center was talked about a lot. The Mainichi and Asahi newspapers, I think it was, covered it. You know there was no TV in those days, or rather it existed, but very few people in Japan had one, so they used to show these newsreels before or after movies at the movie theater. We were featured in one of those. After that concert they interviewed us, and they also filmed us performing at Harumi Pier or somewhere. A review of us ran in a mainstream newspaper. We got that degree of attention.

The “John Cage Shock” is a fiction!

Kaneda: At that time, did you already have the perception that Group Ongaku was engaged in something very innovative?

Tone: Yes. We really did! We thought everyone in the music world was a bunch of old fogeys. You know, the phrase “John Cage shock” was hogwash they made up. On the other hand, there was a man named Hewell Tircuit who wrote a music column for the Japan Times. I think he still lives in Japan. He said what Cage was doing was something that had been developing in Japan for quite a while, and I’m sure he was making a veiled reference to Group Ongaku. So, the whole notion of “John Cage shock” was a fiction! Cage’s music and ideas weren’t such a shock—Japanese people accepted them with relative ease. After all, Cage himself said that Japan was the first country to recognize and understand what he was doing.

Kaneda: Was there a particular mentality that made Japan very open to Cage’s music?

Tone: Well, one thing was that with the political turmoil surrounding the 1960 U.S.–Japan Security Treaty, there was a progressive mindset of rejecting the old and welcoming the new, even among the general public. The anti-treaty movement was a huge one, even by global standards. Sixteen million Japanese people took part in the movement between 1959 and May 1960. I believe that this political situation had an impact on the general mentality.

Kaneda: Did you see Group Ongaku as very political during this period?

Tone: I have a funny story about that. The 20th-Century Dance people held a symposium and let us speak at it. A man named Yamano Hakudai asked, “What do you people think about engagement?” He used the French word, meaning political engagement, but I intentionally misconstrued his words to mean audience participation in a performance rather than political participation, and I answered his question in this way. I wanted to make the point that thanks to the political environment at the time, artists were being asked questions like his, and the role of artists was changing. As old hierarchies of composer, performer, and audience were broken down, we were becoming aware of new creative possibilities. I think his question led me toward things I later did, like composing music with graphic notation and creating event pieces.

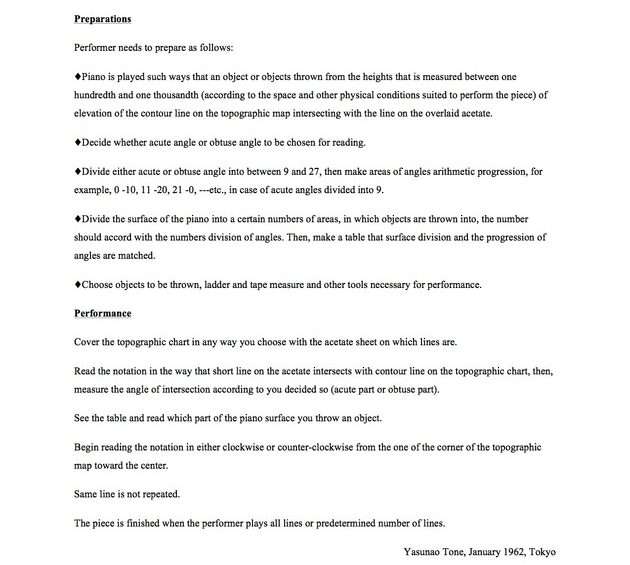

Graphic notation generates unexpected sounds and unpredictable actions

Kaneda: Did you write your first musical scores using graphic notation?

Tone: That’s right.

Kaneda: Did graphic scores composed by other people inspire you?

Tone: Actually, I don’t think I had seen any. I had only heard about them, from Ichiyanagi Toshi and so on. Ichiyanagi told me, “In the U.S., there are guys who do nothing but events.” I thought, “Doing only events sounds all very well, but seeing as how I’ve been doing music thus far, I’d like to compose music and then place it within the context of the event.” In a case like that, I’d like to have people that are not professional musicians do the performing and be working with a clear concept. To do that, graphic notation seemed like the most appropriate method.

Kaneda: Did you have a lot of opportunities to hear European avant-garde music at that time?

Tone: I did. For example, in the late 1950s, Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Kontra-punkte was performed at Tokyo Video Hall, a small concert hall located in or next to the Asahi Shimbun building in Yurakucho. When I went to see it, I ran into Mizuno Shuko. I knew him by sight, since we were in the same year at Chiba University. We both said, “Hey, I didn’t know you were into this kind of thing.”

In those days, Shibata Minao, who hadn’t yet become an art school professor, was doing a long-running program on NHK [Nihon Hoso-Kyoku (Japan Broadcasting Corporation)] to introduce listeners to contemporary music. I used to listen to that all the time.

In high school, I had wheedled my dad into buying me an LP record player. That was in the early 1950s, around 1951 or so, so I must have been fifteen or sixteen. The first records I bought were Bartók, Prokofiev, and then they had these jazz EPs…I still remember I had Duke Ellington’s “Take the A Train.” When I first came to New York and rode the A subway line, I thought to myself, “I’m actually taking the A train,” and I was overcome with deep emotion. The record I owned actually had Dave Brubeck on piano, not Ellington, but in any case, that’s the kind of thing I was into.

Kaneda: Would you say that the music you performed with Group Ongaku was a kind of reaction against the music you had been listening to?

Tone: I think we were trying to say that we were completely different and we had no relation to anything that had come before. Though when I first got to know her, Shiomi Mieko would talk about Brahms and things like that. She had been brainwashed [laughs]. And Takemitsu Toru asked us, “Why don’t you guys play jazz?” I told him, “What we do isn’t jazz, man. It’s tango [laughs].” And he said, “Oh, I forgot, you’re a bunch of Surrealists” [laughs].

Kaneda: Was that a joke? Or were you serious?

Tone: As a matter of fact, Kosugi Takehisa had a part-time job playing the violin in a tango band called Orquesta Tica or something. He was literally playing third fiddle, and during actual performances they wouldn’t even let him produce any sound. He told me, “If I actually play, they get angry with me” [laughs].

Kaneda: Even nowadays, we hear a lot about the “John Cage shock” and the extent of Cage’s influence in Japan, but earlier, you distanced Group Ongaku from Cage. Can you say a little more about that?

Tone: At first I thought John Cage was irrelevant, but when I actually listened to his music in depth, I realized how great he was. I had started writing graphic scores at that point, and I noticed that Cage’s work was quite close to the kind of thing we were attempting to do. I came to admire John Cage.

Kaneda: Judging by Cage’s 1963 lecture “Contemporary Japanese Music,” edited by Fred Lieberman, which he delivered after returning to the U.S. from Japan in 1963, Cage had a lot of admiration for you and Group Ongaku.

Tone: People’s influence on one another is mutual, and even if they’re in a teacher-student relationship, it’s possible for the student to influence the teacher. For him to admire what we were doing doesn’t seem strange to me.

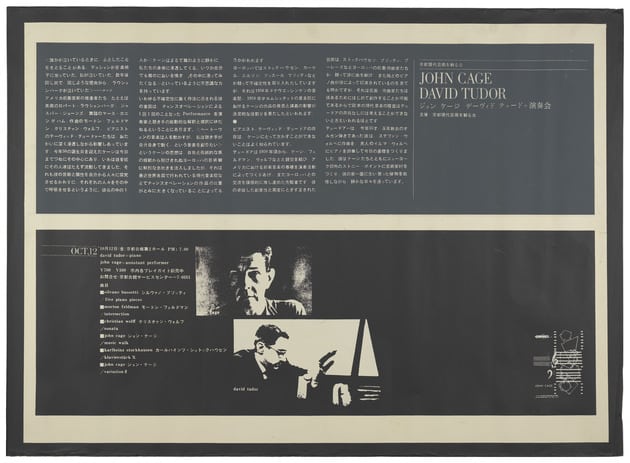

Cage came to Japan along with David Tudor, and Tudor’s piano playing was quite incredible. The combination of Cage’s compositions and Tudor’s performance was really something else. It blew me away.

Kaneda: Contemporary musicians today are now quite accustomed to forms of graphic notation, but the majority of them do not seem to be interested in the graphic score as such. Some go as far as saying that the music that results from a graphic score is just not that interesting. Conversely, Cage’s scores and other graphic scores are presented in museums as works of art. What do you think is the ideal way of dealing with a graphic score?

Tone: This can’t be a matter that’s limited to graphic scores. It has to be about works in general. In a graphic score, if the concepts are crystal clear and can easily be grasped in visual form, the graphics aid the task of performing the piece. There are some people who just look at art, as well as some who just listen to music, and some who do both. However, when it comes to people that only listen to music and don’t know much about art, you’ll find that their attitude toward art hasn’t evolved past the nineteenth century. That means they might look at the most intriguing work of art and find it uninteresting. For that matter, if you ask someone about something outside their limited areas of interest, they’ll always say it’s uninteresting [laughs]. If you abandon the format of staff notation and write things in graphic notation, or even just as a set of instructions, the range of possibilities for performers’ actions expands so as to be almost limitless. It’s fascinating. However, whether it’s a set of instructions or a graphic score, it’s not too interesting if you can look at it and easily imagine what it’s going to sound like. The great thing about graphic notation is that it generates unexpected sounds and unpredictable actions.

Kaneda: Was there a score for the piece Tape Recorder, which you showed in the 1962 Yomiuri Independent exhibition?

Tone: What I did was take a lot of tape recordings of my piece Anagram for Strings and create a thirty-minute loop wound inside a plastic case that I then placed on top of a tape recorder. The case was placed on top of the tape recorder instead of the reels, and the tape threaded through the pickup in such a way that it produced sound indefinitely. The music is all stringed instruments performed by the members of Group Ongaku.

Kaneda: Group Ongaku’s music is improvisational, and the sound is somewhat similar to that of British free improv. However, it seems as if you arrived at that sound by a different route. Did you have any interactions with British musicians?

Tone: I never did. I used to look down on them [laughs]. When I saw MEV [Musica Elettronica Viva] at Cunningham House, I thought, “What on earth makes this group so famous?” With Group Ongaku, when things aren’t going well during a performance, like when everyone gets too carried away producing noises and the volume suddenly rises, we all notice and put a stop to it. Their performance was like that all through. Group Ongaku had decided long before that we had to stop that kind of thing, not to get worked up by what the other members were doing and start going overboard. We made a conscious decision that each member would produce his or her own sound without being affected by the surrounding sounds. That is, each of us listens to the others, but we don’t react to each other directly. If you react, then the music becomes indistinguishable from jazz.

“In Paik’s concert, I played one of La Monte Young’s pieces, which involves pushing a piano around. The instructions were along the lines of ‘Simply keep pushing the piano, and if you come to an obstacle, keep pushing until you get through it.’ I followed these instructions and pushed the piano as hard as I could up to the wall and then kept pushing so it would break through. It didn’t go the way Young planned it, though.”

Kaneda: What events at the Sogetsu Art Center made a particularly lasting impression on you?

Tone: Well, at the time when John Cage was in Japan, I was particularly struck by a piece composed by La Monte Young. It involved dragging furniture and other objects. That was really something. Another one was Takahashi Yuji playing Cage’s Winter Music. I’d have to say that was the most impressive performance I’ve seen of one of Cage’s compositions. The sounds are all disjointed and seemingly unrelated to one another. I thought to myself, “Hey, this guy is doing exactly the same thing as me.” When I played the sax, I tried my hardest to play without any distinct melodic line. I went about it by playing one very fast passage with all sorts of disparate sounds packed into it, so that it was both extremely fast and sonically diverse, with twenty to thirty different noises produced per second. But there is no continuity, and there are intervals between them. When Takahashi performed Winter Music, he banged out a series of tone clusters at intervals of two minutes or so, which he timed with a stopwatch. I can’t remember if that was before or after John Cage came to Japan.

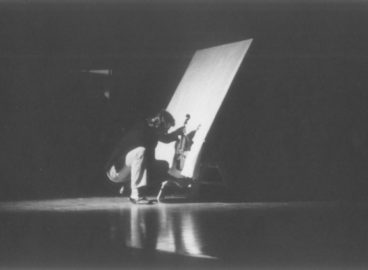

Also, La Monte Young had a piano piece that had the performer kowtowing. That’s a Chinese style of bowing where they kneel, fold their arms across their chests, and prostrate themselves so their heads touch the floor. In that piece, the performer kowtows and then plays the black keys with his right hand and the white keys with his left hand. Nam June Paik played that piece at his [Paik’s] concert, and it made a great impression on me. In Paik’s concert, I played one of La Monte Young’s pieces, which involves pushing a piano around. The instructions were along the lines of “Simply keep pushing the piano, and if you come to an obstacle, keep pushing until you get through it.” I followed these instructions and pushed the piano as hard as I could up to the wall and then kept pushing so it would break through. It didn’t go the way Young planned it, though.

Kaneda: It seems like it would only take a little while for you to push the piano to the wall [laughs]? But the Sogetsu piano was a very expensive Bösendorfer, wasn’t it?

Tone: Well, they wouldn’t let us use the Bösendorfer for something like that. For that I used a plain, cheap upright piano. The Bösendorfer, that was specially ordered—it was a sight to see. It looked more like a red, white, and blue sculpture than a piano.

Kaneda: Could you tell me a little more about the Paik concert that you just mentioned?

Tone: Paik selected the performers himself, and they were like a who’s who of avant-garde music. First came Ichiyanagi’s concert, then Yoko’s, and then Nam June Paik’s. Paik’s was the most artistic.

Kaneda: What was the piano destruction like?

Tone: It was beautiful. Spectacularly beautiful. Aesthetically sublime.

Kaneda: What do you mean by beautiful?

Tone: Well, I think he had made incisions with a saw beforehand so that it would fall apart properly. Then he sawed and hammered at it, and when there was an impact on the strings inside, they made this drawn-out, flanged sound like the scraping of a plane, which was truly beautiful. Finally, he attacked it with the hammer until it fell apart. Only the strings didn’t come off; they were attached to a steel frame and remained intact. The performance was sonically and visually gorgeous. The destruction of a piano is a spectacle like the collapse of a cathedral ceiling. It’s not at all violent.

Paik also has a piece called Solo for Violin, where the performer waves a violin around like a sword and smashes it: wham, it shatters and falls apart. I performed it once myself in a Fluxus concert during the Fluxus Festival at the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague. A violin is flimsy, so it comes apart easily. When I first saw this piece performed, I thought they had made cuts in advance so it would smash more easily, but in fact it doesn’t need it. When it comes to the piano, though, I’m sure he prepared it by making cuts or something in advance, or else it wouldn’t go so smoothly.

“Until [1972] I considered myself anti-American because of the Vietnam War.”

Kaneda: When did you first start hearing about Fluxus?

Tone: Ichiyanagi came back to Japan from New York, and he and I got to be very good friends. And he told me that George Maciunas wanted one of my works. I asked him who Maciunas was, and he told me he was this really flaky artist. He did things like filling a bathtub with water, floating oil paint on the surface, then putting a canvas face down on the water and calling the results an “instant painting.” A really out-there artist, but he got things done. If he said he was going to do something, he did it. I didn’t have a lot of work at that point, so I sent him Anagram for Strings. That and a few pieces of tape music. Maciunas kept telling me to send him something, and I was at a bit of a loss as to what to do.

Kaneda: And that led to your getting involved with Fluxus.

Tone: After that I went to New York and met Maciunas, who said he was really glad I could make it. We went to 80 Wooster Street in SoHo, and we talked about all kinds of things. Maciunas often put on all kinds of events and Happenings at 80 Wooster. He was living in the basement, and Anthology Film Archives was on the ground floor, run by Jonas Mekas. They had an event there called the Fluxus Olympics, with activities based on various sports. Maciunas built a tandem bicycle for it. I bought this toy drum and used it in place of the ball in a game of volleyball.

Kaneda: Did you first visit New York in 1972?

Tone: That’s right. Until then I considered myself anti-American because of the Vietnam War.

Kaneda: What prompted you to visit the United States?

Tone: Over a two-year period starting in 1971, I was working on a fifty-year chronology of contemporary art for Bijutsu Techo magazine. When you’re doing something like that, you stop producing work of your own. You even stop being able to write. You get bogged down, creatively stagnated. Until then I had been making a living as a writer, and I thought, “I could write just as well in New York.” I happened to attend this puppet play, I can’t remember if it was by the Yuki Magosaburo Company or Hitomi-za—in any case, it was held in Kichijoji, Tokyo. Afterward, I was talking with some people including Takiguchi Shuzo and Nakanishi Natsuyuki. And Takiguchi asked me, “Tone, don’t you ever go overseas?” And I answered that I needed a reason to go. Nakanishi never went abroad either, and he said he saw no reason to, unless it was to a country with great coffee [laughs].

Well, after that I started thinking about how I hadn’t been abroad, and Takiguchi was encouraging me to go. While I was thinking about this, I got a pamphlet in the mail saying there would be a design conference in Aspen, Colorado, the World Design Conference. I was writing about this for Bijutsu Techo and Design Hihyo as well, and I told them I’d be going to Colorado for a week or so to cover it. After the design conference was over, though, I thought it would be dull to go back to Japan right away, so I stuck around for this event called the Aspen Music Festival. Before I left Japan, people had told me New York was hot in the summer, so why didn’t I check out San Francisco? And so I did.

Sakurai Koshin, a member of the Kyushu-ha, had started a commune in San Francisco. I think he moved to San Francisco around 1965. It was one of the first hippie communes, called the Konnyaku Commune. Sakurai founded it along with two other people, a Filipino poet called Al Robles and a Rinzai Zen monk named Gisen. When I was departing for the U.S., I heard that this commune still existed, so I wrote them a letter saying I would visit, and then I called when I arrived in San Francisco before going to Aspen to say I’d be stopping by afterward. They said I should by all means visit on my way back. I planned to spend about a month there as a summer vacation, but I ended up staying until November, six months in all.

Kaneda: When did you next come back to Japan after that?

Tone: It was about seven years before I got back.

Kaneda: Did you bring a lot of things with you?

Tone: Actually, I lost all kinds of things, like books and photographs of things I had done in the past. The only things that survived were a few things my younger brother just happened to be keeping. I have those still. The rest is gone.

Kaneda: What was your life in New York like?

Tone: I wasn’t thinking at first about how to make a living, but my wife followed me to the U.S. and stayed with me for about a month in San Francisco; then we went to New York. At first we were living on savings, but then I got sick and had to be hospitalized. Shortly before that, I had gotten to know a woman named Thais Lathem, who was the director of the Intermedia Art Institute in New York. She let us rent the ground floor of the institute cheaply, for just one hundred dollars a month or something [laughs]. We moved in there, and then I got sick and had to enter the hospital. I couldn’t speak English, though, and I didn’t know what to tell the doctor, but Nam June Paik rushed to the hospital by taxi and interpreted for me. Thais negotiated with the welfare office and took care of my medical fees.

Oh, yes. I had gotten to know Thais through Nam June. She told me, laughing, about meeting Fukuzumi Haruo, the senior editor at Bijutsu Techo. She had been contacted by the U.S. State Department, who told her that a high-ranking editor at Japan’s top art magazine was going to visit and instructed her to meet him. She waited for him at the Intermedia Art Institute office and was surprised when the person who stepped out of a limo was this little bearded fellow in a rumpled army jacket.

Kaneda: Was there already quite an extensive community of Japanese artists in New York at the time?

Tone: There was, though I was wary of associating with them. After all, the reason Japanese people can’t speak English is that they always isolate themselves in these Japanese communities. In the commune in San Francisco, they had a bit of diversity, I suppose. There was a black painter, a white hippie girl, and her boyfriend, a former coal miner from West Virginia with a very thick accent. Then there were five or six Japanese people from the neighborhood who would get together. Sakurai Koshin asked me to give a lecture to these young Japanese people and “educate” them [laughs]. At that time the journal Shiso (Thought) had just published a Japanese translation of Louis Althusser’s “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses” in their June and July issues, and I suggested we all study that. That’s an example of why I didn’t make progress in English at first. My English is still rotten today, to tell the truth. In the experimental music community in New York, though, at least there weren’t a whole lot of Japanese people.

Kaneda: I get the impression that Fluxus and Maciunas were very accepting of Japanese artists.

Tone: Maciunas actively sought our work, as I mentioned, and Japanese artists were participating in Fluxus just like any other members, at a time when, in general, there was little recognition for artists from outside America and Europe. One reason for this is that Maciunas had a certain interest in Japan. For example, he was fascinated by the Shoso-in collection of national treasures in Nara, and he had the idea of creating a collection of Fluxus art that would be like a contemporary Shoso-in. He also came up with the name for Neo Haiku Theater, a short Fluxus event, which was inspired by Japanese haiku poetry. There’s no doubt: Maciunas took an active interest in Japanese culture. Rather than say that he accepted Japanese artists into Fluxus, I think it would be more accurate to say that he explicitly sought Japanese artists to join Fluxus. And not only Japan; he also did various things in other countries, for example in Wiesbaden, in Copenhagen, in Paris, where the early Fluxus concerts took place.

When he asked us Japanese artists to send him work, and we did, that was still before Fluxus had even gotten started. Fluxus was formed around 1962, right? It was in 1961 that he asked us for work. So at that time, we didn’t think it was such a big deal just because we were getting attention from overseas—after all, there was little audience for our work there. In Japan, in contrast, when we played a concert at Sogetsu in Tokyo, there was a full house. And as for my concert at the Minami Gallery, the proprietor, Mr. Shimizu, thought it would make an ideal opening event for his new gallery space, but I wasn’t taken with the horseshoe-shaped layout of the new space, so I got him to hold it in the old Minami Gallery in the building next door, which was still unoccupied. There was a big audience there as well. By comparison, I heard from Ichiyanagi Toshi that La Monte Young, for example, had a piece for nine musicians where there were only four people in the audience, and the performers surrounded the audience so that they couldn’t leave. In that sense, we were more famous in terms of media attention. Funny, isn’t it?

The Sogetsu Hall seats about four hundred, and we had a full house at our concert. You wouldn’t see that in New York even nowadays! The audience for avant-garde music in New York was really negligible, so just to be hearing from a guy in New York wasn’t particularly thrilling.

Kaneda: So it was Maciunas who sought out Japanese artists for Fluxus, not the other way around?

Tone: Maciunas was basically the brains behind Fluxus, and my impression is that he was more or less responsible for pulling various people together and forming a group. Some people who disagreed with Maciunas, like La Monte Young, ended up dropping out. Dick Higgins was expelled at one point as well. And Kosugi Takehisa sent Maciunas some work towards the beginning but was purged.

Kaneda: Why was that?

Tone: I guess there was a strong element of sectarianism, you know? And there was animosity between Maciunas and Charlotte Moorman, so when Kosugi took part in Moorman’s Avant-Garde Festival as soon as he arrived in the U.S., that rubbed Maciunas the wrong way, I suppose.

Kaneda: Did you maintain a good relationship with Maciunas?

Tone: Yeah, it’s hard to say why that is. To Maciunas, Fluxus was not art. It wasn’t a career—it was something to do for fun after working an eight-hour day job. If you were an artist, then you could spend eight hours a day making art and then do Fluxus in the evening. The idea that Fluxus itself was art was completely out of the question. That’s why he had no objections if I was doing things that were geared toward the mass media, since we weren’t supposed to be in the business of making high art anyway.

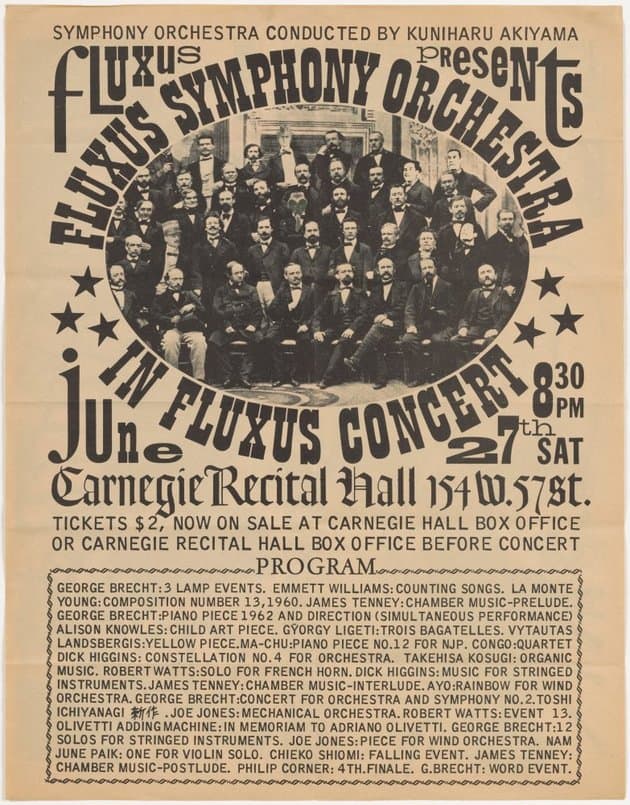

Kaneda: Did you take part in Fluxus activities in Japan before you went to New York?

Tone: Fluxus was formed in late 1962. Akiyama Kuniharu went to New York in 1965, I think it was, and he participated in the Fluxus Festival that was held at the Carnegie Recital Hall. There were reports on that in the Yomiuri Shimbun and so forth, so there was a degree of knowledge about Fluxus in Japan. Then, in 1966, or maybe it was 1965, something called Fluxus Week was held at the Crystal Gallery in Ginza. What grabbed everyone’s attention at that time was Nam June Paik’s Opera Sextronique—no, no, it was Serenade for Alison, dedicated to Alison Knowles. It had a female dancer, one of Kuni Chiya’s troupe, wearing seven pairs of panties that she stripped off one by one in a kind of striptease. The dancer said she was embarrassed and didn’t want to do it, but Ichiyanagi persuaded her, saying something like, “The whole point is that an ordinary girl is doing it. There’s nothing interesting about a professional stripper shedding her panties.”

Kaneda: So who ended up doing it?

Tone: It was a woman by the name of Nakahara, one of Kuni Chiya’s dancers. Kosugi Takehisa had become infatuated with her, and for his sake I asked her on a date to go see West Side Story, but then I didn’t go and Kosugi went in my place to meet her at a coffee shop. I can’t remember clearly, but I think things didn’t go well at all, and he came back without even taking her to the movie.

The idea for the soundtrack to Adachi Masao’s Gingakei was based on a computer flow chart

Fluxus in Japan wasn’t well known as an active group like the one in New York. I was interested in introducing Fluxus to Japan, but I was more focused on making my own work. And I was busy earning money as well, for example, making music for a television commercial.

Kaneda: What kind of commercial was it?

Tone: One of those things with mint in it, you know, to prevent bad breath—like candy, breath mints. And the person who was in charge of the commercial also got Takeda, Sugino, and Shiomi to compose music…

Kaneda: What kind of music did you do for the commercials?

Tone: Pretty simple stuff, sounds like the flourish of a vibraphone and things like that. We were just pulling things out of a hat. I can’t remember clearly what we did [laughs]. Then there were film soundtracks. There was this Tokyo extra-governmental organization called the Tokyo Metropolitan Film Institute, and Adachi Masao was working there part time. They had this weekly Tokyo cinema news report, and I did music for that.

Kaneda: You also did music for one of Adachi Masao’s Gingakei (Galaxy)?

Tone: That was fun to make. I showed Adachi my idea for the soundtrack, which wasn’t computer music but was based on something like a computer flow chart. Then I asked a jazz critic named Aikura Hisato to get together some young jazz musicians, and they improvised. All of them became quite famous later, but at the time they were still unknown.1According to music critic Aikura Hisato, the performers for this piece were Nakamura Seiichi on clarinet and tenor saxophone, Moriyama Takeo on drums, and Aikura Hisato on piano. Nakamura and Moriyama started their careers as members of the famed Yamashita Yosuke Trio shortly after working on the film.

Kanesaka Kenji had a film called Hopscotch, right? The sound for that was recorded at Sogetsu, at the Sogetsu Hall film studio or somewhere. Okuyama Junosuke did some sound engineering, and then there was this circle of people we formed to work on the music for Hopscotch, and people were given instructions to prepare to play something. The Japanese word for play is hiku, and it can have multiple meanings. People asked what it meant specifically, and I said it could mean a lot of things depending on the context. For example, if you say ocha o hiku, it means “to grind tea.”2In Japanese, Ocha o hiku is an expression used to describe a sense of boredom when business is slow for entertainers such as courtesans and performers (i.e., when one has nothing else to do but grind tea [to make matcha]). I told them it was up to them what to hiku. So Takamatsu Jiro did subtraction problems on a blackboard (hiku also means “to subtract”), Kanesaka Kenji and some others played Japanese traditional playing cards (hiku can mean “to take [a card]”) [laughs], and Togashi Masahiko pulled the trigger of an air gun (hiku can also mean “to pull”). My idea was to do color subtraction applied to sound. I made a chart correlating colors to sounds. If you subtract red from purple, you get blue; if you subtract blue from green, you get yellow; and so forth. So I would do the subtraction and then produce the corresponding sound. We recorded all these various sounds and used this as the source for the soundtrack.

Kaneda: Did you interact with a lot of jazz musicians?

Tone: Not a lot, though I did play the piano for one of Kara Juro’s plays at the request of Aikura Hisato, along with some other jazz musicians. Ri Reisen, one of the actresses, complained that I made noise with the piano every time she was delivering a line [laughs]. They never asked us to perform again!

Translated into English by Colin Smith; transcribed by Yu Yamaguchi

- 1According to music critic Aikura Hisato, the performers for this piece were Nakamura Seiichi on clarinet and tenor saxophone, Moriyama Takeo on drums, and Aikura Hisato on piano. Nakamura and Moriyama started their careers as members of the famed Yamashita Yosuke Trio shortly after working on the film.

- 2In Japanese, Ocha o hiku is an expression used to describe a sense of boredom when business is slow for entertainers such as courtesans and performers (i.e., when one has nothing else to do but grind tea [to make matcha]).