John Cage and David Tudor visited Japan in October 1962 at the invitation of the Sogetsu Art Center (SAC). Over the course of the month they gave seven concerts in Tokyo, Kyoto, Osaka, and Sapporo, causing a sensation that would become known as “the John Cage shock.” But even before the legend settled in, documentation had already been arranged. Cage recalled that a photographer “snapped everything from the time I got off the plane with David.”1Quoted in Kenneth Silverman, Being Again: A Biography of John Cage (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2010), p. 184. The photographer, Yasuhiro Yoshioka, was commissioned by SAC to accompany Cage and Tudor everywhere they went. At the end of their stay, Yoshioka compiled his photographs in two albums as a present for Tudor—one focusing on sight-seeing and the other on performances. Together, the volumes constitute a visual record of an itinerary that was soon reduced in most accounts to a simplistic narrative of shock. A selection of images from the albums, which are now part of the David Tudor Papers at the Getty Research Institute, is presented here.

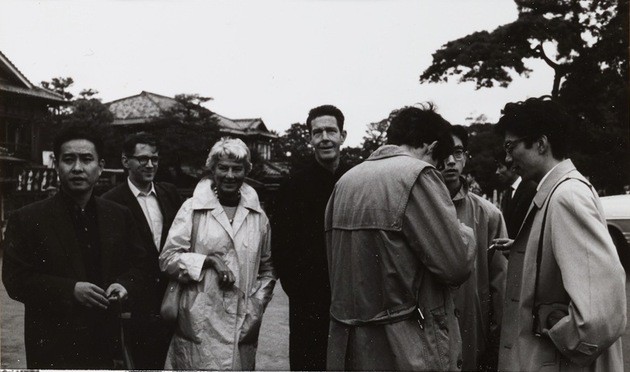

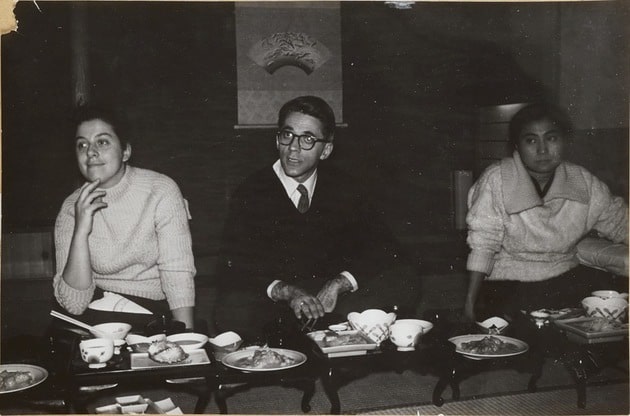

Album 1 begins with a photograph of Cage and Tudor being greeted at the airport by violinist Kenji Kobayashi and Yoko Ono. At the time, Ono was married to Toshi Ichiyanagi, a composer who had studied with Cage in the U.S. and was instrumental in organizing Cage and Tudor’s trip. The next images show the visitors at a meeting at SAC and then enjoying various welcoming events, including a “geisha banquet.”2Quoted in Being Again, p. 184. Cage found his hosts “unbelievably imaginative in finding ways to make our visit enchanting,”3Quoted in Being Again, p. 183. and Tudor sent a similar report to his then-partner, M. C. Richards: “They are treating us wonderfully & also it seems that it’s also very nice for them because everything here has to be specially arranged & we are thus sometimes introducing them to their own culture—(geishas & all that).”4David Tudor, letter to M. C. Richards, October 25, 1962. David Tudor Papers, Box 58, Getty Research Institute.

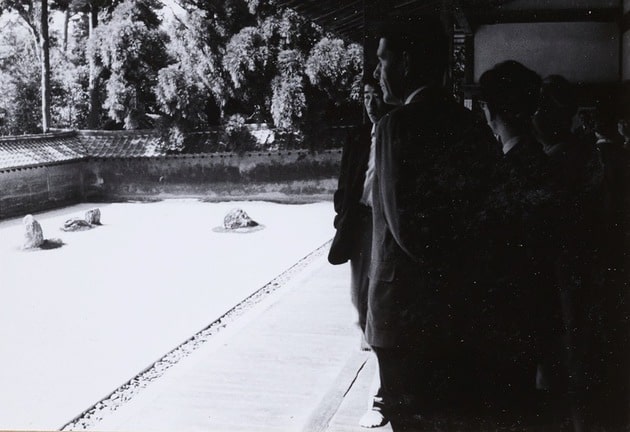

Following their two initial concerts at Tokyo Bunka Kaikan (October 9 and 10), Cage and Tudor traveled south, accompanied by Ichiyanagi and Ono and by Cage’s friend Peggy Guggenheim. They gave a concert in Kyoto (October 12), and another in Osaka (October 17). In their free time the group visited temples in Kyoto and Nara. Ryōan-ji, a Zen temple famous for its rock garden, left a profound impression on Cage, but he was not convinced that the placement of the fifteen stones within it was in any way particular. Whether or not he was informed that the stones had been arranged with the utmost care to make it impossible for a viewer on the veranda to see all fifteen of them at once, Cage opined to a Japanese critic “that those stones could have been anywhere in that space, that I doubted whether their relationship was a planned one, that the emptiness of the sand was such that it could support stones at any points in it.”5John Cage, “How to Pass, Kick, Fall, and Run,” in A Year from Monday: New Lectures and Writings (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1967), p. 137.Cage still held this view twenty years later when he composed the score of Ryōan-ji (1983) by tracing the contours of fifteen rocks whose positions he determined by means of chance operations.

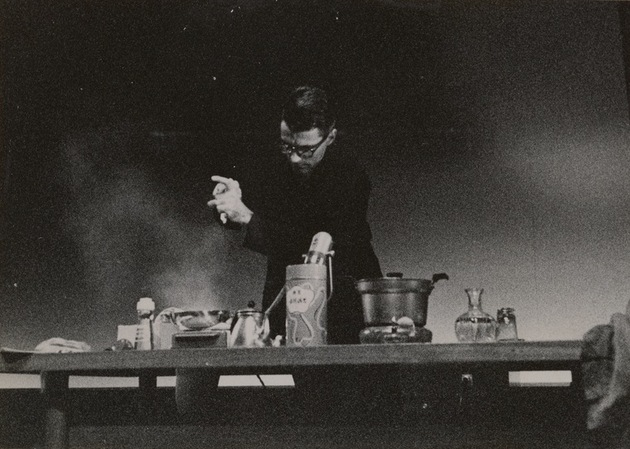

At Ryōan-ji Cage was drawn instead to the apparent “emptiness” of the sand: “I was now coming to the realization that there was no such thing as non-activity. In other words the sand in which the stones in a Japanese garden lie is also something.”6John Cage, Michael Kirby and Richard Schechner, “An Interview with John Cage,” The Tulane Drama Review 10, no. 2 (Winter, 1965), p. 64. His interest in the invisible micro-activity of the sand rather than in the rocks’ conspicuous visual array reflected a general shift in the composer’s aesthetics. In his own work, he was abandoning parametric measurements and using amplification to convert incidental sounds from daily life into “music.” These features would form the basis of 0’00’’ (4’33’’ No. 2), composed in Japan and dedicated to Ichiyanagi and Ono. The original score consisted of the following statement: “In a situation provided with maximum amplification (no feedback), perform a disciplined action.” Cage himself premiered the work at SAC on October 24; his action consisted of writing out the instructions for the very piece he was performing, with contact microphones attached to his pen, eyeglasses, and other objects.

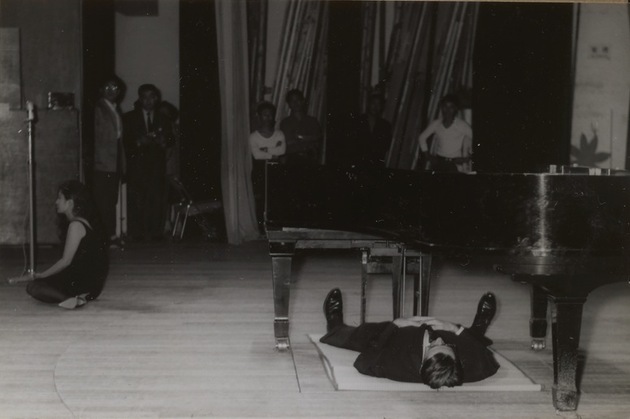

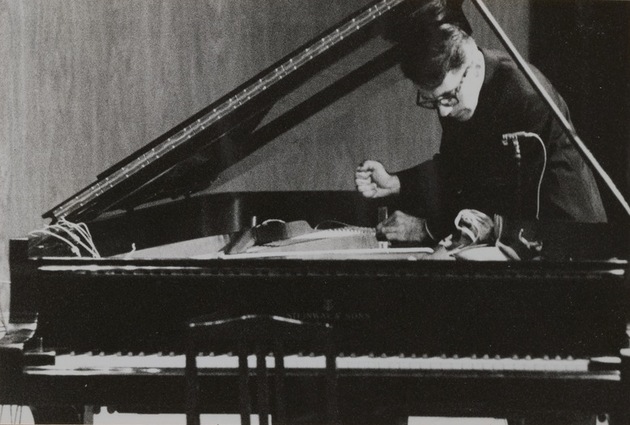

Album 2 starts with photographs from the first two Tokyo concerts, documenting performances of Cage’s Music Walk and Atlas Eclipticalis with Winter Music. These images are followed by photographs from the Osaka concert: Ono singing Cage’s Aria alongside Tudor, who is performing Cage’s Solo for Piano and Fontana Mix simultaneously; and a shot of Tudor and Cage performing Cage’s Variations II. A few photographs from the October 23 and 24 concerts at SAC are included, all showing Tudor performing Theatre Piece.

Ironically, one of Cage and Tudor’s most significant encounters in Japan, their meeting with SAC sound engineer Junosuke Okuyama, took place off-camera. Cage held Okuyama in high esteem, later describing him as “one of the finest engineers I’d ever encountered”7John Cage, “Contemporary Japanese Music: A Lecture by John Cage,” in Yayoi Uno Everett (ed.) Locating East Asia in Western Art Music (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2004), p. 195. and “who if the Lord knew His business would be multiplied and placed in every electronic music studio in the world.”8John Cage, “Happy New Ears,” in A Year From Monday, p. 34. One particular conversation with Okuyama inspired Cage to extend the approach taken in 0’00’’ toward the micro-activities of apparently mute objects: “[Okuyama] remarked one day that he thought using contact microphones in musical compositions was very interesting, but what seemed to him more interesting yet was the use of such fine microphones that one would be able to place one on a piece of wood, for instance, and . . . make audible the interior vibrations of the wood itself.”9Cage, “Contemporary Japanese Music,” p. 196. Like the stones and sand at Ryōan-ji, this idea would make a lasting impression on Cage.

The American composer found something “typically Japanese” in Okuyama’s thinking.10Cage, “Contemporary Japanese Music,” p. 196. Like the shifting of his gaze at Ryōan-ji, Cage’s view of what constituted “Japanese” fluctuated. On the one hand, Cage felt that, just as the fifteen stones could have been placed anywhere in the garden, it did not really matter from which country a composer came. “The situation music finds itself in in the United States and Europe, it also finds itself in in Japan. We live in a global village.”11Cage, “Happy New Ears,” p. 33. Those who connected “the accident that they’re Japanese”12Cage, “Happy New Ears,” p. 33. with their music were therefore fixating on a particular outcome of chance: the circumstance of their birth. On the other hand, Cage also maintained that, like the sand supporting the stones, being Japanese amounted to “something” that persisted beneath the constant relativization of the global village. He expressed this view mostly in relation to Ichiyanagi, the only Japanese composer who, according to Cage, had “found several efficient ways to free his music from the impediment of his imagination” (including any connection Ichiyanagi might have drawn between his music and the fact that he happened to be Japanese).13Cage, “Happy New Ears,” p. 34. For Cage, this achievement made Ichiyanagi’s work something of a paradox: “The world now has a Japanese music which is universal in character, but which is Japanese and not European.”14Cage, “Contemporary Japanese Music,” p. 198. Perhaps by accident, this assessment echoed a “typically Japanese” notion about being Japanese proposed by none other than D. T. Suzuki, Cage’s teacher of Zen. According to Suzuki, Zen was not only the spirit of Buddhism but also comprised the universal ground of all religious truths. At the same time, it typified the unique essence of Japanese spirituality—a koan-like claim that was developed in complicity with Japanese nationalism.15See, for instance, D. T. Suzuki, “A Reply from D. T. Suzuki,” Encounter 17, no. 4 (1961), pp. 55—58. Robert H. Sharf has analyzed how this attitude was coupled with the ideology of Japanese nationalism during the years leading up to the Second World War: “The claim that Zen is the foundation of Japanese culture has the felicitous result of rendering the Japanese spiritual experience both unique and universal at the same time. And it was no coincidence that the notion of Zen as the foundation for Japanese moral, aesthetic, and spiritual superiority emerged full force in the 1930s, just as the Japanese were preparing for imperial expansion in East and Southeast Asia.” “Whose Zen? Zen Nationalism Revisited,” in James W. Heisig and John C. Maraldo, eds., Rude Awakenings: Zen, the Kyoto School, & the Question of Nationalism (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1995), p. 46.

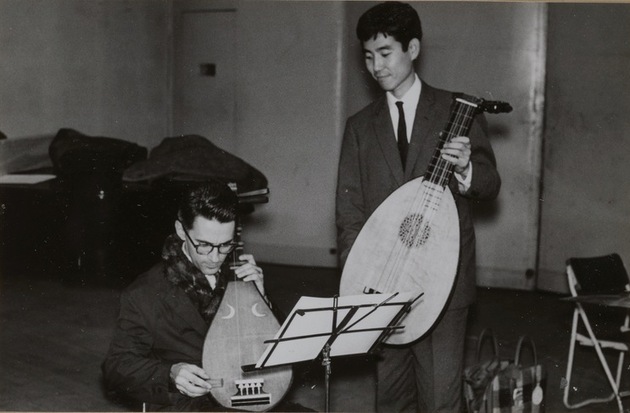

Tudor maintained his usual reticence in Japan, but the recordings of his performances there seem to bespeak a distinct concern.16The SAC and Osaka concert recordings can be heard on John Cage Shock, vols. 1–3, 2012, EM Records, EM 1104, 3 CDs. In contrast to 0’00”, in which the level of amplification was preset to exclude feedback so that accidental sounds could be made audible, Tudor’s realization of Variations II, (using the amplified piano) foregrounded real-time control of the process of amplification and the manipulation of its resulting feedback. In other words, his focus was on the particular (electronic) devices and instruments that came between, and mediated, the sand and the stones. During the final days of the Americans’ visit, Yoshihara documented a pertinent encounter Tudor had in Japan. Album 2 ends with photographs of the rehearsal and performance of Ichiyanagi’s piece Sapporo in the city of the same name. Tudor is seen here playing the biwa, a short-necked “Japanese” lute that was imported from China in the seventh or eighth century, and whose roots can be traced further back to India. As a musical instrument, the physical specificity of the biwa Tudor came in contact with was neither globally interchangeable nor universally Japanese, but rooted in the particular history of its trajectory. Tudor indeed brought the biwa back to the US, and played it at least on one occasion (the performance of Sapporo during the Tudorfest held at the San Francisco Tape Music Center in April 1964). Throughout his life, Tudor revisited Japan on numerous occasions, but temples were not where he spent his time. Concealed inside many electronic instruments Tudor built are material evidences of these trips: components and kits that he purchased in Akihabara Electric Town every time he returned to Japan.

The author would like to thank Rosaly Roffman for kindly sharing her memory of the Hokkaido trip with Cage and Tudor.

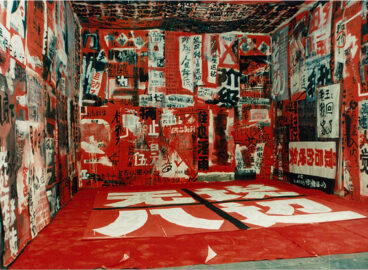

Album 1

Album 2

- 1Quoted in Kenneth Silverman, Being Again: A Biography of John Cage (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2010), p. 184.

- 2Quoted in Being Again, p. 184.

- 3Quoted in Being Again, p. 183.

- 4David Tudor, letter to M. C. Richards, October 25, 1962. David Tudor Papers, Box 58, Getty Research Institute.

- 5John Cage, “How to Pass, Kick, Fall, and Run,” in A Year from Monday: New Lectures and Writings (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1967), p. 137.

- 6John Cage, Michael Kirby and Richard Schechner, “An Interview with John Cage,” The Tulane Drama Review 10, no. 2 (Winter, 1965), p. 64.

- 7John Cage, “Contemporary Japanese Music: A Lecture by John Cage,” in Yayoi Uno Everett (ed.) Locating East Asia in Western Art Music (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2004), p. 195.

- 8John Cage, “Happy New Ears,” in A Year From Monday, p. 34.

- 9Cage, “Contemporary Japanese Music,” p. 196.

- 10Cage, “Contemporary Japanese Music,” p. 196.

- 11Cage, “Happy New Ears,” p. 33.

- 12Cage, “Happy New Ears,” p. 33.

- 13Cage, “Happy New Ears,” p. 34.

- 14Cage, “Contemporary Japanese Music,” p. 198.

- 15See, for instance, D. T. Suzuki, “A Reply from D. T. Suzuki,” Encounter 17, no. 4 (1961), pp. 55—58. Robert H. Sharf has analyzed how this attitude was coupled with the ideology of Japanese nationalism during the years leading up to the Second World War: “The claim that Zen is the foundation of Japanese culture has the felicitous result of rendering the Japanese spiritual experience both unique and universal at the same time. And it was no coincidence that the notion of Zen as the foundation for Japanese moral, aesthetic, and spiritual superiority emerged full force in the 1930s, just as the Japanese were preparing for imperial expansion in East and Southeast Asia.” “Whose Zen? Zen Nationalism Revisited,” in James W. Heisig and John C. Maraldo, eds., Rude Awakenings: Zen, the Kyoto School, & the Question of Nationalism (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1995), p. 46.

- 16The SAC and Osaka concert recordings can be heard on John Cage Shock, vols. 1–3, 2012, EM Records, EM 1104, 3 CDs.