In the second half of an extended interview with Tone Yasunao for post, the composer, artist, and writer discusses the trajectory of his work from graphic scores in the 1960s to his recent work with digital media. Since his earliest experiments, Tone Yasunao has consistently been poised to question expectations about music, art, sound, and performance, long before “performance art” or “sound art” were terms in the art lexicon. Tone discusses his encounter with a callous music publisher from Peters Edition, and his first solo exhibition at the Minami Gallery, where he combined performances based on graphic scores, experiments in electronic music. He also shares stories about a road trip with Shigeko Kubota and Nam June Paik, and his early encounters with Foucault, Wittgenstein, as well as grammatology through ancient Chinese poetry books that he found in used bookstores in Chinatown. Exclusive video documentation of Tone’s performances of his work since the 1960s and archival material from the artist’s personal archive accompany this interview. The interview was held at The Museum of Modern Art on February 10, 2013 by Miki Kaneda.

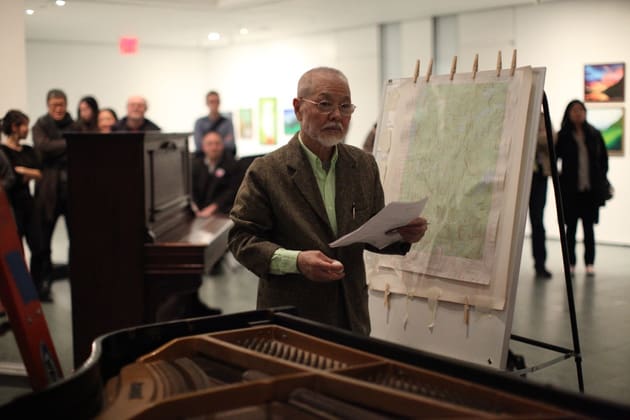

Miki Kaneda: I’d like to ask you about your music activities since the 1960s, and about some of the pieces you performed in the concert at MoMA last month [January 2013].

Tone Yasunao: That reminds me . . . I was invited by Peters Edition to publish a score. After I received the invitation, Peter Peterson, whom I learned was the president of Peters Edition, came to Japan looking to publish scores by Japanese composers. There was a music school called Ueno Gakuen, which was run by the father of Fukushima Hideko and Kazuo. They were having a party there and I was told to go, and so I did. Then the guy from Peters saw me and thought I was this kid, and so he asked me, “How old are you?” That pissed me off, and so I ignored him completely.

Kaneda: When was that?

Tone: Around 1963 or ’64, I think, after John Cage went back to the U.S. So I think the people who Cage named were asked to go to that party. The younger brother of Fukushima Hideko, Kazuo, was there, too. Ichiyanagi Toshi was also there. Mayuzumi Toshirō, too. When Mayuzumi saw that I was upset, he made sure that the guy knew I had graduated from Geidai. Apparently, he thought that that was my alma mater even though it actually wasn’t. Now that I think about it, George Maciunas wrote me a letter saying something along the lines of “the Cage school” is going to be over soon, and so don’t bother publishing in a place like Peters Edition.

Kaneda: Is that a reason you declined?

Tone: Well, that, too, but also, my English wasn’t that good. I thought it was too much work to translate all the instructions into English.

Kaneda: But Maciunas published your scores in English. How did that work out?

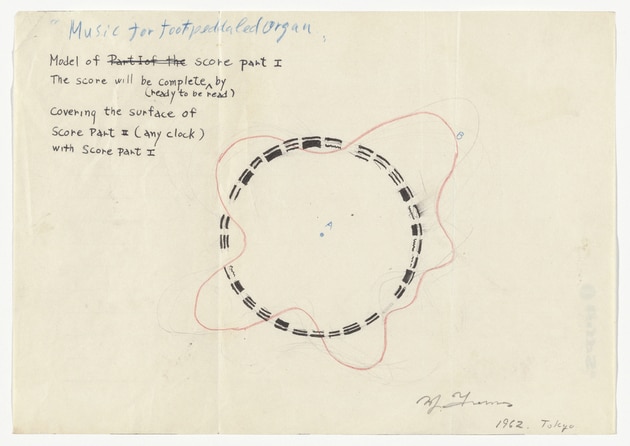

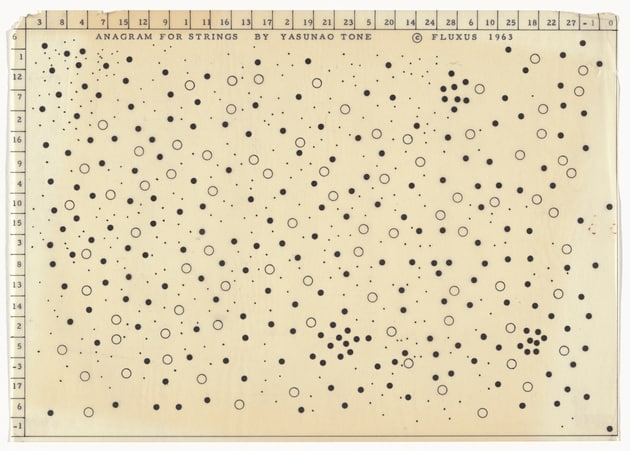

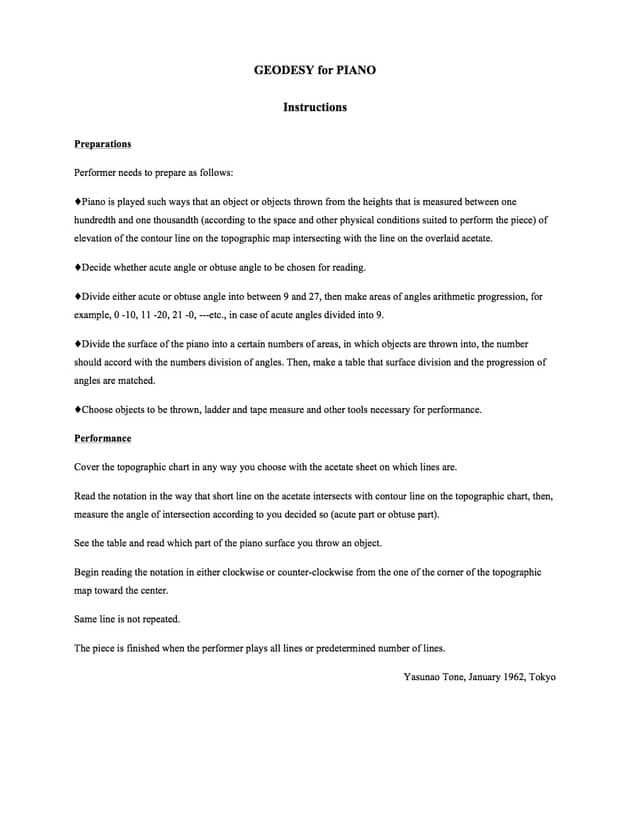

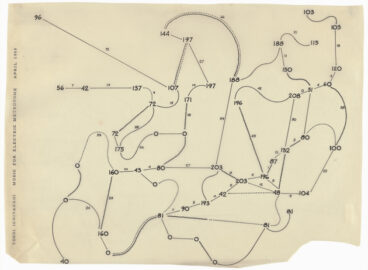

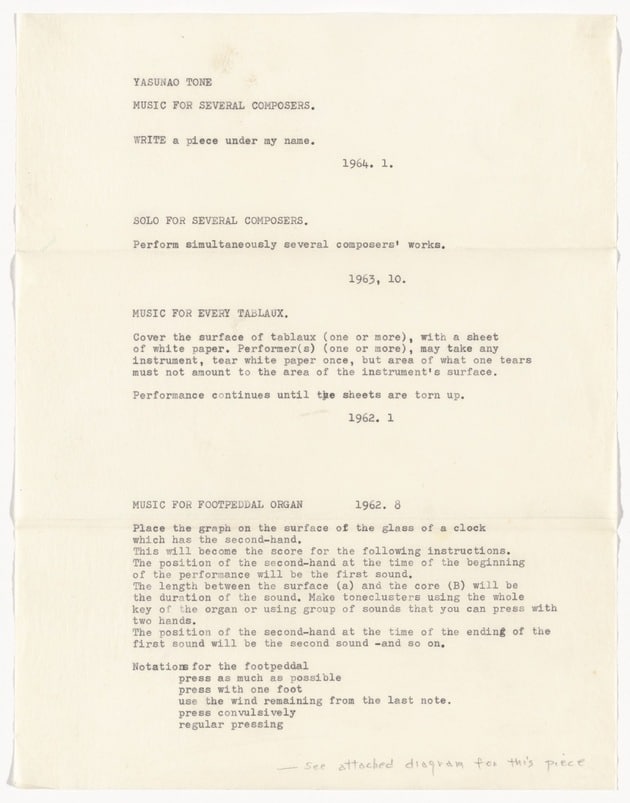

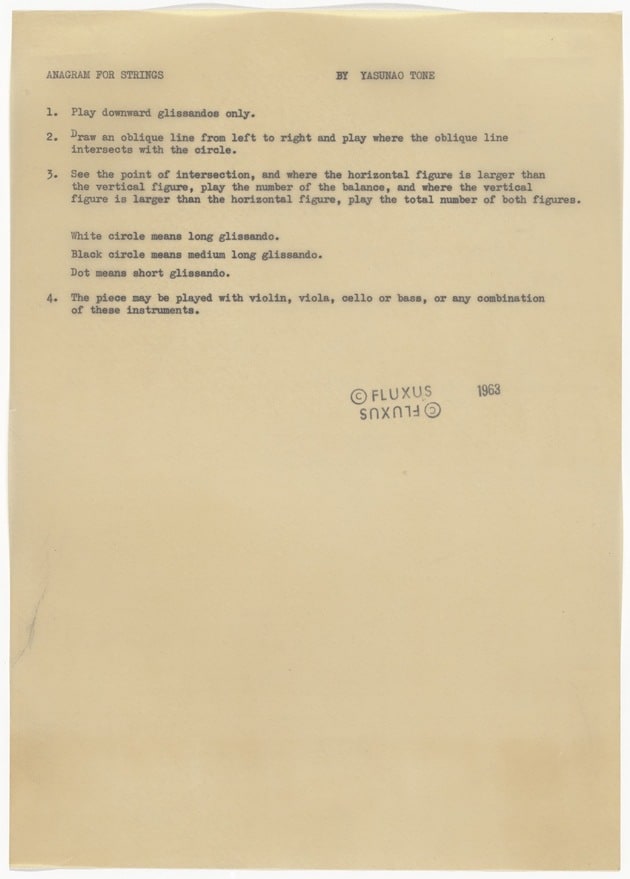

Tone: Oh, that was Yoko [Ono]. I think she did those for me. We didn’t have access to a typewriter, and so I think Maciunas took her handwritten text and typed it out. That score of Anagram that you have at MoMA has a Fluxus Edition stamp on it. So Maciunas probably reproduced it on the basis of the score that I sent to him. Also, you know the scores that have textual instructions, such as the Music for Reed Organ piece? Those were translated by Yoko as well. But the longer and more complicated ones, like Geodesy, I didn’t send. For the ones that did make it to Maciunas, Yoko suggested having a GI guy send the scores by the military mail because it was the cheapest way. It turned out the GI was Jeff Perkins.1Jeffrey Perkins is an artist and filmmaker living in New York City who took part in Fluxus activities.

Kaneda: Speaking of Fluxus Editions, did you ever make any money from being involved in that?

Tone: Not at all! I received a letter from Maciunas saying that one score would sell for something very little . . . under a dollar. And he said that we would split the profit evenly.

Kaneda: Well, that doesn’t sound like such a bad deal for Maciunas!

Tone: But I’ve been thinking, if I had taken the opportunity to publish through Peters, I might have been labeled as part of the “Cage school,” and it might have been harder for me to start doing my original work.

Kaneda: Is that something that you were thinking back then, too?

Tone: No. When I was younger, I used to go back and forth and think that maybe I should have accepted the offer to publish through Peters. Once I arrived in America, though, I had it in my head that I had to do something completely new and different from the past. One of the first things that I did was to work with Merce Cunningham. But at Mills College I did do some of the things that I had been doing in Japan, like the cutting piece Music for a Painting. Bob [Robert Ashley] was at Mills College. At that time it was a women’s college, and they had a graduate music program. Among the graduate students at Mills, Paul DeMarinis, “Phil Harmonic” [aka Kenneth Werner], and Jon Bischoff were also there and performed my pieces for my concert. The interesting thing was that even with my poor English, people understood easily what I was trying to do.

Kaneda: How do you think the most recent performances of Smooth Event and Anagram at MoMA compare to performances of your work in the past?

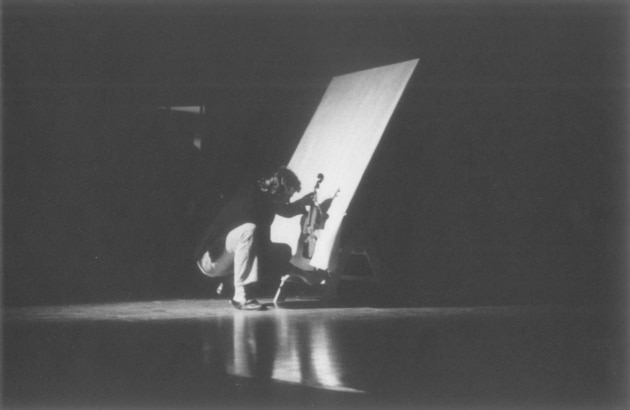

Tone: You know, I think it might be better now. Before, it used to be too “musical.” For example, in something like Anagram, the glissandi are supposed to flow like a river.

Kaneda: Do you mean sonically?

Tone: Well, I was thinking of it more as a concept, like the monochromes of Yves Klein or the achromes of Piero Manzoni—something that doesn’t change, that isn’t allowed to progress. In Anagram, well, I think there were some people who were trying to make ugly sounds on purpose, and I’m not sure about that, but when you listen to it, it’s not “musical.” I like that.

Kaneda: Anagram and Smooth Event have been performed a number of times since you first composed them. Can you talk about some of the other recent performances of these pieces?

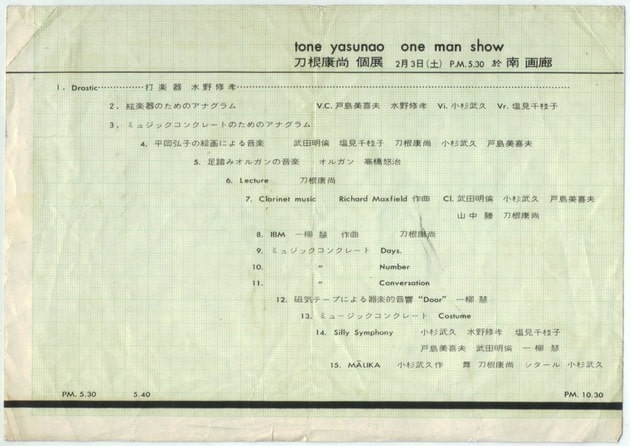

Tone: Joan Jeanrenaud, a former member of the Kronos Quartet, performed Anagram. Also, a video documenting Smooth Event was shown along with Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, Hans Haacke, etc. at the exhibition Iron Works at the Anne Reid Gallery in Princeton, New Jersey, in 2003. When Anagram and Smooth Event were performed at the Minami Gallery in 1962, I also presented pieces called Silly Symphony and Drastic. For Drastic, the idea was to take drastic laxatives and then bang on a drum to hold off from going to the bathroom during the performance. The title Drastic is a combination of drumstick and drastic laxatives. Mizuno Shūkō, who performed the piece at that time, took about five to eight minutes. It’s a good thing there was a bathroom right behind the wall next to where the performance took place at Minami Gallery! The audience could hear the flushing sound.

Kaneda: I received some feedback from people who attended the recent concert at MoMA, and while Fluxus concepts are quite well-known and understood, some people mentioned that having to sit through it and experience it was a very different thing. Grasping something intellectually is totally different from being put in a situation where you have to deal with your own reaction to the experience of the piece, whether it’s boredom or frustration.

Tone: Well, if you want boredom, it should have gone on longer! But that wasn’t the goal. The idea was that it’s just one thing and unchanging.

Kaneda: At your MoMA performance, everyone except for Lary Seven was playing with you for the first time. I was interested in your process—that there was no rehearsal and only minimal discussion leading up to the event. It seemed like a purposeful decision.

Tone: If someone takes a piece that I wrote a long time ago and does it the same way now, well, that’s fine by me, but I was wondering what it means for me to also be committed to the performance as a performer. But if there are young people who aren’t intimately familiar with my old work, instead of telling them how to play it, I wanted them to interpret the score based on what they’ve experienced and what they’ve learned in their lives so far. It’s kind of an experiment to see how they would respond to it, and I was really interested in seeing how that panned out. So it’s not that I didn’t tell them what do on purpose, but rather that I was curious to see what would happen, and I didn’t want to give the impression that they had to do as I said.

Kaneda: All the pieces in the concert were from the 1960s, but there was one piece that was paired with you performing MP3 Deviation, a much more recent project, along with the rest of the ensemble improvising. Could you please explain how MP3 Deviation works?

Tone: There is a sound source and a computer program for the piece. The sound source is related to the idea that I wanted to do something totally new when I came to the U.S. I decided, “Now that I am here in America, I don’t want to make works for somebody else, just for myself.” Anyway, around that time I also went to Paris. That’s when David Behrman was the music director of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. He sent me a letter asking me to do something for the next year’s season. That was probably Cage’s idea. Behrman had also heard about the Mills College concert and told me, “I heard that you did something really interesting at Mills.” He probably heard about it speaking on the phone with Bob [Ashley]. It hadn’t even been a month since I had come to New York.

I went to New York at the end of 1972, and before that, in November, I did my concert at Mills. In January or February, Cage and David Tudor had a concert at the State University of New York Albany campus, and I went with a bunch of friends in a car rented by the management company Performing Art Services [a not-for-profit management organization which represented Robert Ashley and other artists]. Ay-O and, I think, David Behrman were also in the car. Nam June Paik and Shigeko Kubota and my wife were in the car, too. Shigeko used to be Kosugi’s girlfriend. Then she married Behrman. After she divorced Behrman, she became Paik’s girlfriend. Kosugi didn’t come because he had gone back to Japan around 1967. He didn’t come back to the U.S. until 1977. Eventually, Shigeko married Paik. It was funny because in the car Paik was joking about making a band with Kosugi and Berhman and calling it something like the “Shigeko Brothers.”

Kaneda: Was Shigeko-san laughing?

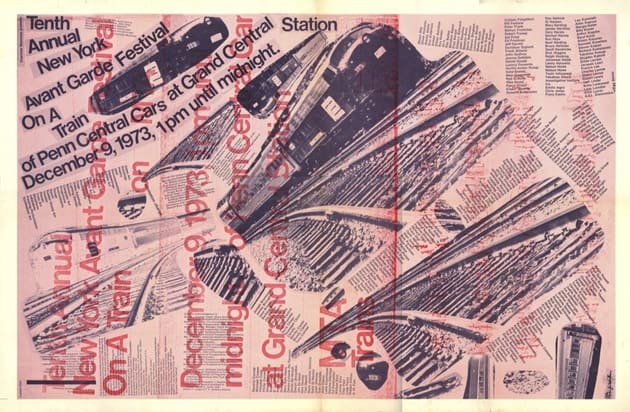

Tone: That kind of thing doesn’t faze her at all. She was complaining that it was all Japanese guys in the car, and then Paik protested that he wasn’t Japanese. But she ignored it. This was around the beginning of 1973. In the summer of 1973, Kudo Tetsumi was in Paris. He wrote to tell me that New York is nice enough, but why didn’t I come to Paris. And so I went to Paris with my wife. This was around the time of the Bastille Day festival, le quatorze juillet in French. The first thing I did after coming back from Paris was the Avant-Garde Festival at Grand Central. At that time I did two pieces that were just instructions based on the idea of a counter–Doppler effect because I had heard that we were going to borrow train cars and do the concerts inside them. But then it turned out that they didn’t move; they were just boxcars, and so it didn’t go according to my plan.

Tone: For the counter-Doppler piece, the idea was to make a sound with your voice each time the train passed another train. The voice was supposed to do the opposite of the Doppler effect. With the Doppler effect, when a moving vehicle approaches, the sound gets louder, but in this case, you were supposed to do the opposite and make your voice softer when the train passed and raise your voice gradually again as it moved away. So it’s a hard piece.

Kaneda: But the trains didn’t move, and so then what happened?

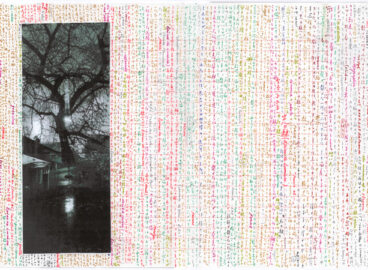

Tone: We just pasted the instructions on the wall of a boxcar, along with instructions for the piece titled One Day Wittgenstein, which I performed with two other participants at Grand Central Terminal Main Concourse. That was all! It was simply conceptual. That was kind of leaning toward a kind of text-based music, right? Next was a piece for the Merce Cunningham concert. There is a book called Dada by Hans Richter, and I made a piece looking at that. This was a video piece that I made for a two-day Cunningham event. Using a pulley system, I used three turntables, each moving, respectively, according to the second, minute, and hour hands of a clock. The turntable going according to the seconds would make a full rotation every minute. I placed a video camera on the turntables. This idea came from the space of the Cunningham Studio, which has a stage on one side and a full mirror on the other side. I put the turntables right by the mirrors and the image goes around half in the real space and half in the virtual space of the mirror. All the while, the camera is reflects both real and virtual spaces. I had this visual idea first, and then I made a text based on “Theatrum Philosophicum,” Latin for the “theater of philosophy.” This was a text by Michel Foucault on Deleuze. I took some passages from Foucault’s text and combined them with a text of mine called “On Looking at Photography” (Shashin o miru koto ni tsuite), which appeared in a magazine called Shashin Eizō. It’s also in my book Gendai Geijutsu no Isō (1970).

After this, when I was asked to do this piece again, I didn’t use this text but instead used a nude woman videotaped in three parts: the head was one part that was rotating once an hour, the body was another part, and the legs were moving once a second or something like that. Those images were projected onto a monitor and each piece was rotating at a different rate; once every hour, they would come back together. The piece is based on René Magritte’s painting of a nude woman’s body divided into three separately framed images, I called this piece Clockwork Video à la Magritte. Then I added a new text for the piece. So these are the beginnings of my work with “text” in music, or so-called textual music.

Then I did a piece at Phil Niblock’s Experimental Intermedia Foundation. I thought of using text, and so I thought about the title Voice and Phenomenon. The title is the same as Derrida’s book, but the rest is totally different. Mine was based on the Tang poems in the collection Tōshisen.

This was what I consider my really original project that no one else had done. I decided that now that I had come all the way to New York, I would not work for anyone but myself, and I would not do things that someone else had already done.

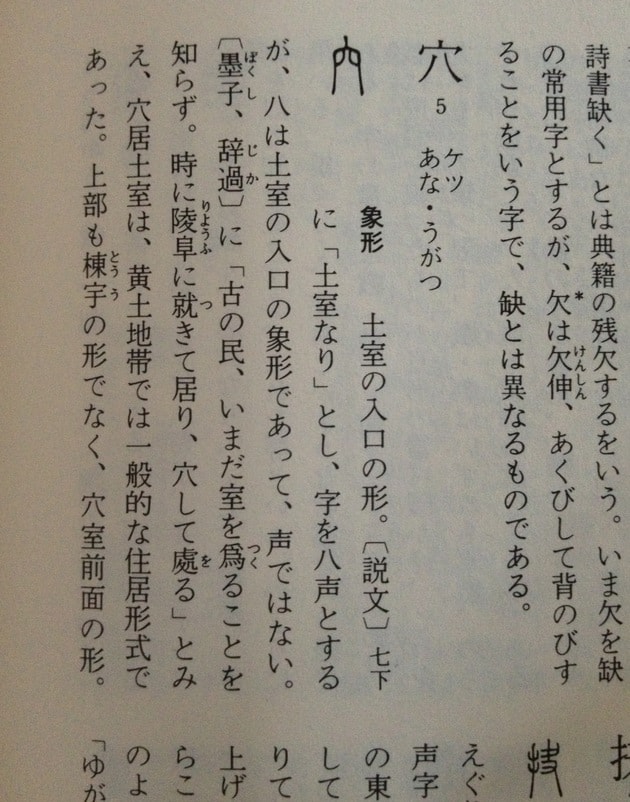

Around that time, Shirakawa Shizuka, an East Asian Studies scholar, published a book called Kanji through Iwanami Shinsho that I found at Tokyo Shoten, a Japanese bookstore on Fifth Avenue near 50th Street in New York. Shirakawa talks about how kanji [Chinese characters] came to be from an ancient ethnographic perspective. Shirakawa was a very esteemed scholar. After I came across this book, Nam June Paik told me that Shirakawa was a very important person, and that since he was getting old, he should make a video while Shirakawa was still alive. But then Nam June died before Shirakawa, who lived into his mid-nineties and was an honorary professor emeritus of Ritsumeikan University. Reading Shirakawa’s book, I started thinking about how I might use this idea of Derridian grammatology for myself. I found the analysis of kanji to be very interesting. Normally, when you think of the kanji character for sky, you think the character is just a representation of the sky. But think about it—if you made an image of the sky with a cloud in it, how are you going to tell if the character is supposed to represent the sky or a cloud, right? So when you look at the term sora 空 (sky) it’s the word ana (hole) 穴 combined with kō 工 as in kōgu 工具 (tool). Shirakawa explains how these parts came to mean “sky” by going back to ancient Chinese bronze inscriptions and oracle bone script.

Kaneda: What were the images that you projected?

Tone: The images were based on the kanji. I researched all the origins of the parts of the characters based on Shirakawa Shizuka. Some of them were not in his first book. There is a set of hardcover books by Heibonsha called Kanji no Sekai, and two volumes about the history of ancient Chinese bronze inscriptions and oracle bone script called Kōkotsu-bun no Sekai and Kinbun no Sekai, also from Heibonsha. I also used Setsumon Kaiji, a five-volume Chinese reference book about the origin of characters, which dates back to the early second century. I used both of those sources to look up all these characters. This took a very long time!

Then, I developed this piece to turn the images into sounds by putting CDS light sensors on a screen. They are sensors that detect light and convert it into an electric signal. I connected that to an oscillator to make it into sound, and I amplified that through a PA system. When you screen that, the kanji turns into a sound.

Kaneda: So this is the basis of all of your music since the early 1970s!

Tone: Yes. When I released Musica Iconologos in 1993, I had already been working in this way for a while, and my question was whether I could do something similar using a digital process on a computer. This was right after Steve Jobs got kicked out of Apple and made the NeXT Cube on his own, not at Apple. It was all black and a very cool-looking computer. I used this machine. I wanted to make digitize an image and use the computer to turn that into sound. I had to find someone who could write a program to do this kind of thing. Tudor introduced me to one of his assistants, who was a student at McGill University in Montreal. At McGill there was an electronic music studio that I was free to use. I had an assistant, because I wasn’t very proficient at using their system. McGill had developed a program that recognized patterns, like pitches, or English characters. There was a Japanese-Canadian scholar, Fujinaga Ichiro, at McGill who made that program. Using that program to read images and characters, I then generated histograms—a kind of bar graph. Fujinaga’s program was combined with another program called Projector to read the wavelike shape of the histogram as a sound wave. Scanning an image, the program would read the digitized result and produce sound. One image becomes one histogram, which produces sound. The outcome of this project was released by Lovely Music as Musica Iconologos (1993).

Kaneda: What I find fascinating and perplexing is how in all these stages before the sound that we as listeners have access to, you are dealing with very concrete objects like images and characters and their histories. But when you hear the resulting sounds, which are very noisy, there is no way to hear any reference or connection to the original images and texts. How can we make sense of this relationship between the sound and the images that generate the material for the sounds?

Tone: First of all, if you wanted to create completely random sounds, that’s actually very difficult to accomplish because of habit and taste: if there are things that you found while you were messing around and that you liked, you might want to produce them again. I wanted to remove those tendencies but still remain very precise about my method. When I make music, I don’t start with an idea about a sound I want to make. Rather, I want there to be both rigor and differentiation in the sounds. If you start worrying about references between sound and the source, then it starts to be no different than what old-fashioned composers do, namely, representation as re-presentation.

Kaneda: But what do you make of a situation like your recent performance of Improvisation with MP3 Deviation? Your own contribution was based on MP3 Deviation, and so you could say that you yourself were not responding to the other players, but what about the interactions between others in the group?

Tone: We just happened to be in the same place at the same time. It was juxtaposition. This was true of when Group Ongaku members were working with Kuni Chiya’s dance company. When we were making the music, we weren’t looking at the dance at all.

Kaneda: That’s the method that Cunningham and Cage used in their collaboration.

Tone: Exactly. And so when I learned about that, it was not a surprise at all. As Group Ongaku, we were doing the same thing in the early 1960s. But it wasn’t that much of a conscious choice. It was also all we could do.

Kaneda: Why did you choose to work specifically with MP3s as opposed to any other digital format?

Tone: Before MP3s, I developed an idea while working on a project called Solo for Wounded CD. The CD wasn’t released until 1997, but the piece has been performed live since 1985. While I was preparing for the concert, I found a Japanese paperback titled Mijikana Kagaku Zeminaru (A science seminar for the familiar) by Hashimoto Hisashi, and I was intrigued by the author’s remark on digital recording. According to the author, digital recording is an excellent device, but a mistake in the numeric value will lead to a totally different and unusual sound. This became an idea for the new piece. When there are scratches or other marks of damage on the CD, the CD reader or CIRC [Cross-Interleaved Reed-Solomon Code], an error-correcting system, “corrects” these spots. I had a friend—a rich Chinese guy, who had a Swiss-made CD player from early on. I wanted to know how to override the correcting function of CD players. An engineer friend of his told me that if you poke tons of pinholes on the surface of the CD and then put little pieces of Scotch Tape on the CD’s surface and hit “play,” the CD player tries very hard to “fix” the files. But if there are too many errors in the original, then the errors will override the player and cause unexpected sounds. And so I tried it, and it worked. It took some time, but I figured out how to make different kinds of sounds this way. I would make twenty CDs, and maybe one would work. Sometimes the machines would just spit out the CD. Maybe I’m inefficient. Everything takes a lot of time for me. But it’s like that for things like Japanese pottery, too. The craftsmen make hundreds, and only one or two of them make the cut.2The piece is fully described in the liner notes of the CD. Back then, in 1985, there were no CD burners and no CDRs, and so I used commercial CDs.

Later, as an alternative to using the program made by Dr. Fujinaga, I tried going more directly from the characters using a sound-editing program called Sound Designer II. You can see what it looks like if you look inside the CD cover of my self-titled album released on Asphodel. This process makes things sound very good. In addition, you can do very detailed manipulations. Using a WACOM tablet with a stylus with the pencil function, I wrote out the characters in the Man’yōshu [the oldest existing collection of Japanese poetry]. So I used the flow of the characters as the sound-wave forms. I used this process for one of the tracks on the album. These sounds became the main source sounds for my later work, the album titled Yasunao Tone, released by Asphodel in 2002.

With MP3s, I figured out how to corrupt the file between the encoder and decoder using a program developed in collaboration with researchers at the New Aesthetics in Computer Music research group (NACM) at the University of York, in the U.K. When a file is corrupted, you get an error message inside the program, and so we used the program errors. The program converts the error messages into designated numbers. We used twenty-one different categories of error messages, and so we made the numbers one through twenty-one of the messages convert to designate the sample length for the sounds. When a sound file is corrupted, we made it so that degrees of corruption are adjustable with percentages ranging from 1 to 100. For example, if a text is converted to the number 2346, then that becomes the length of a sample sound of the original. Then there is another parametric change we use, and that determines the speed of the designated sample played. If the number is one, then it plays at the same speed as the original sample. If it’s two, then the playback speed is twice as fast, and so on. Another device in the program is inversion of polarity; in one sample, you invert the polarity with a certain duration of the waveform, and it produces a completely different timbre. This process makes it so that the original sounds are converted into something completely different. That’s the main idea—there’s no way to predict what kind of sounds this is going to produce. I wanted each corruption to produce a different sound, but at first, the resulting sounds weren’t very varied, so we had to experiment a bit.

Basically, I want to be able to not repeat the same sounds. And I don’t want habits of representation to get in the way of the music that I’m making. In other words, “representation” is “re-presentation,” which I want to avoid. I want to find sounds that I’ve never heard before.

Kaneda: Some critics who write about you focus on the fact that your music is about the destruction of technology. Related to this, the “noise” that you produce is sometimes described as the sound of this destruction.

Tone: That’s simply incorrect! I just added an important function to the way we use machines—producing errors.

Kaneda: This leads some people to place you in the lineage of noise music, but the processes and concepts behind your music make it seem as if you’re coming from a very different place. It seems like those kinds of connections are based on listening to the sonic product of your work without taking into account the processes or concepts, or the scenes that you’ve been affiliated with. But what has been important in your work for a very long time is this idea of media.

Tone: I’ve been influenced by Walter Benjamin’s “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” The reason this essay resonated with me so much is that I always felt that technologies of reproduction are not merely tools for playback. I see them as technologies for production or creation. Also, when I was young, I read a lot of modernist poetry. There is a poet named Kondo Azuma, and one poem of his that I felt was particularly interesting is a poem called Aoi Shigunaru (The Green Light). This is a poem that is meant to be read out loud. He wrote it to be played on radio. There are some naïve Marxist elements to this, but the main idea goes something like this: Right after the title, before the poem is heard, the listeners are invited to close their eyes and listen. The text of the poem itself is something along the lines of “Ladies and gentlemen, do you know what the green signal means?” At the very end, though, it says, “Ladies and Gentlemen, to those of you who have closed your eyes! / In the depths of your eyes, / What do you see? / Can you see the green light? If you can see it, let us depart / If you can see it, let us go / If you can see it, let us move / If you can see it, all aboard! / But if you cannot see it, there’s nothing that can save you. / You might as well enter into a deep sleep now.”3Kondo Azuma Zenshū (Tokyo: Hobunkan Shuppan, 1987), pp. 66–67. Translation by Miki Kaneda This was amazing to me, because the act of the listeners closing their eyes is outside the text of the poem, but it’s of utmost importance to how the poem works. I’m interested in the things outside music in the same way. Here’s an example. In a piece titled Days, a tape music piece I composed in 1961 and performed for a dance piece by Kawana Kaoru, I tried to accomplish something similar for music. I started by reading the numbers, one, two, three, four . . . all the way to one hundred or two hundred. Once I had finished reading them, I recorded the same recitation of numbers onto a tape at a very low volume. Next, I played back that recording at a very loud volume while recording that plus a new layer of recitation. I repeated this a number of times, always recording low and replaying high. On an open-reel tape, this process produces so much distortion that the tape recorder (an old-fashioned reel-to-reel) placed on the stage literally starts jumping around. I remember somebody commented in a blog that Alvin Lucier did the same thing much later [I Am Sitting in a Room, 1969].

Kaneda: How many repetitions did it take for that to happen?

Tone: More than ten repetitions. At that point, you are not just dealing with sounds. It’s about the action produced by the overstressed tape recorder physically moving as a result of the layering of the tracks.

Kaneda: When this event took place, was the tape player visible to the audience?

Tone: Yes, they could see it shaking.

Kaneda: I noticed that in many of your pieces, including those like Smooth Event, which you recently performed, visible actions and things beyond the idea of music as sound figure prominently.

Tone: That’s right. Normally, when you think of playing the piano, you move your hands in order to make sound. I was more interested in specifying the action. Graphic scores are ideal in that sense because it’s about entering through action, and that’s the piece. Sound is merely a result.

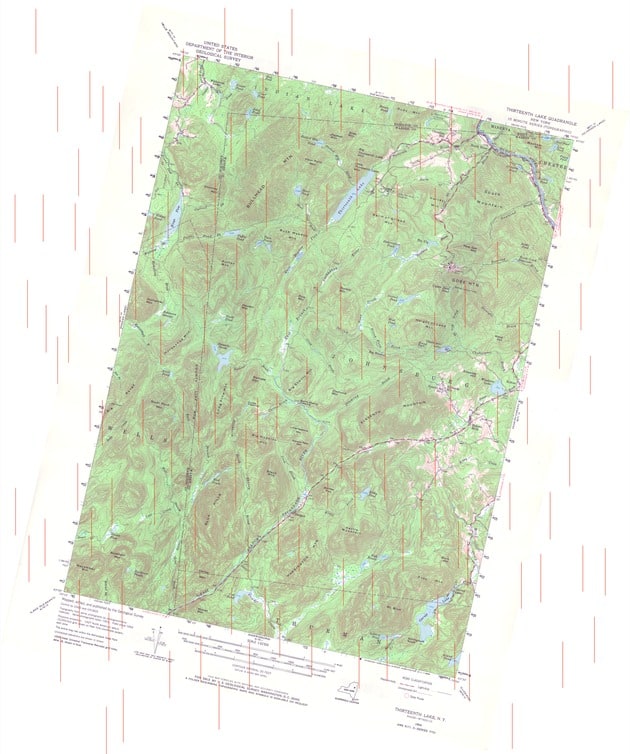

Kaneda: Based on your interest in what is happening around the exterior of a piece, what is the role of the audience for you? Do you consider their reactions as part of a performance? For example, when you performed Geodesy at MoMA, I think there was a general sense of fear from the audience as we watched you ascend a tall ladder to drop things into the piano. I didn’t realize how intense that physical, visceral element of the piece would be in a performance.

Tone: Do you mean because I’m old?!

Kaneda: No. I was afraid for your co-performer, Ning Yu, as well.

Tone: Well, sound doesn’t exist as some kind of abstract entity. In addition, listening to re-presentation of sound is the same thing as listening to a record many times. As a composer, that’s meaningless to me. There are some people who like to listen to the same thing many times, but personally, I think it’s a bit strange that people don’t get bored of doing something like that. It would be great if you could write something that, even if it’s the same sound, turns out sounding different each time you hear it. There are certain things that sound is good for, but it’s very imprecise. In terms of the senses, it’s much rougher than something like vision. You can’t do the same things with sound that you can do with image or text. So there’s always the danger of sound becoming mere representation, which is what I try to avoid.

Kaneda: You’re talking about other ways to understand the idea of music as more than just “sound.”

Tone: Sound is vibrations, and so sometimes people describe things as “noise,” but in a sound coming from speaker cones, there’s already extra sound there, because of the physical movement of the cones. That’s why I think it’s wrong to want to design a concert hall where the audience members will hear the same sound, regardless of where they are sitting in the hall. These kinds of desires are driven by people’s world views, which are informed by certain assumptions about what “music” is.

- 1Jeffrey Perkins is an artist and filmmaker living in New York City who took part in Fluxus activities.

- 2The piece is fully described in the liner notes of the CD.

- 3Kondo Azuma Zenshū (Tokyo: Hobunkan Shuppan, 1987), pp. 66–67. Translation by Miki Kaneda