Mário Pedrosa is widely considered Brazil’s preeminent critic of art, culture, and politics and is one of Latin America’s most frequently cited public intellectuals. Three selections from his writings included here (“The Vital Need for Art”; “Environmental Art, Postmodern Art, Hélio Oiticica”; “The New MAM Will Consist of Five Museums”) come from the anthology Mário Pedrosa: Primary Documents and illustrate his penetrating critical approach to the art of his time. A fourth text, “The Machine, Calder, Léger, and Others,” does not appear in the anthology and is available here in English for the first time.

Mário Pedrosa: Primary Documents is the first publication to provide comprehensive English translations of Pedrosa’s writings. Texts range from art and architectural criticism and theory to political writings as well as correspondence with his artistic and political interlocutors, among them such luminaries as André Breton, Alexander Calder, Lygia Clark, Ferreira Gullar, Oscar Niemeyer, Hélio Oiticica, Pablo Picasso, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Harald Szeeman, and Leon Trotsky.

The Vital Need for Art

In this landmark 1947 lecture, the legendary Brazilian critic and public intellectual Mário Pedrosa advocates a Universalist view of art that includes the creativity of children and the mentally ill. The text also outlines the importance for modernism of what was then called primitive art. Drawn from the recent publication Mário Pedrosa: Primary Documents, this lecture was given on the occasion of the closing of an exhibition of works by patients at the Hospital Dom Pedro II, a psychiatric center in the Engenho de Dentro district of Rio de Janeiro overseen by the Jungian psychiatrist Dr. Nise da Silveira. The artist Almir Mavignier helped establish an art studio at the center in which local abstract artists, such as Abraham Palatnik and Ivan Serpa, actively participated. Pedrosa was central to articulating the significance of the work undertaken by the studio, and he brought several critics like Albert Camus, Murilo Mendes, and Léon Degand to the center to broaden the intellectual appreciation of its activities.

The trouble with understanding the problem that brings us together here today is a conceptualization of art that centuries of bad tradition have implanted in our minds. The reality is that the world today does not know what art is. The public cannot discern what is fundamental about the artistic phenomenon.

To the public, visual art is the imitation of nature—the representation of reality according to certain canons that have been codified since the Renaissance. All so-called works of art are immediately subjected to this criterion and the public wishes to see this confirmed in them—this identification with external reality.

Hence the public’s incomprehension of so-called modern art. And its even greater incomprehension in light of an experiment such as the exhibition currently on view at the Centro Psiquiátrico Nacional.1As of 1946, the Centro Psiquiátrico Nacional Pedro II, located in the Engenho de Dentro district of Rio de Janeiro, contained an occupational therapy unit directed by Dr. Nise Silveira, who opposed controversial treatment methods such as electroshock therapy. Artists who collaborated with the unit included Almir Mavignier, Abraham Palatnik, and Ivan Serpa, as well as Pedrosa himself. In 1952 Dr. Silveira founded the Museu de Imagens do Inconsciente (Museum of images of the unconscious), a study and research center dedicated to the preservation of the works produced in the institution.

It is no longer just the public that finds these paintings and drawings “strange.” Perplexity has even taken hold of the avant-garde, of the unfortunately still narrow circle of enthusiasts and connoisseurs of the visual arts in our educated circles. Where does this perplexity come from? It comes from the dregs of an intellectual prejudice with which the problem of art is approached. We are no longer talking about those who are unable to distinguish a work of art—a legitimate painting—from a lifeless academic imitation. We are referring to artists, critics, and consciously refined connoisseurs with academic backgrounds who nonetheless somehow retain an anachronistic notion of the matter. They are interested only in the result—that is, the finished work—the purpose of which is to be perpetually admired or worshipped in a new fetishism. They see only the masterpiece. To them, art has not yet lost its capital “A.” It continues to be a separate, exceptional activity, and the artist remains a mysterious being enveloped by some mystical or magical halo.

This is a highly—if I may be allowed an awful word—passé attitude, and it, too, is the product of academic mustiness. It derives from a concept crystalized from the Renaissance on: art as social glorification, as the veneration of great men; whether they are begirded by the warrior’s sword or wear the emperor’s crown; whether prince or tyrant, cardinal or saint, etc. From its purposes of glorification—after the disappearance of the glorified; that is, the object of glorification—it was the work of art, in turn, that became celebrated as a new fetish that possessed the additional advantage of reflecting the vanity of its worshippers.

Beginning as tailors who stitched together the glorious mantles of the potentates and heroes of the Renaissance, artists eventually transformed themselves into a closed brotherhood at the service of the aristocracy. And, like every brotherhood, it created for itself specialized interests and fixed regulations that segregated its members from the rest of mortals, keeping others at a careful remove from its secrets. In the absence of their genius, the ways of Renaissance artists were zealously amassed and codified by imitators and mediocre successors: for two centuries or more, academicism propagated itself parasitically upon the accomplishments of that fecund age. Isolated in certain countries, the few artists of genius remained misunderstood and systematically ignored (think of El Greco) by trendsetters, dictators of aesthetic laws, and the proprietors of the academic brotherhood.

The world, however, did not remain limited to the Mediterranean; it eventually came to include America, Africa, and the confines of Asia. New civilizations and their cultures were revealed, penetrating ancient Greco-Roman culture.

Archeology, scientific explorations of every order, whether geographical, anthropological, or sociological, have conquered new territories for human culture, and their discoveries exert an influence on art today at least as profound as the excavations and discoveries of ancient classical statues in the age of the Renaissance. Donatello would not have been Donatello without the revelation of Greek statuary. There has been an exploration of cultural expressions not only of Egypt and the pre-Biblical peoples of Asia Minor, but of India and its cultural ramifications. The West has finally embraced Chinese civilization and its refinements. But it is not only these advanced cultural expressions that end-of-the-century Europeans absorbed.

The Barbarian peoples of pre-Columbian America, of Oceania, of Africa are also considered worthy of interest and, with astonishment, cultured Mediterranean man realizes that they, too, possess art (which thus ceases to be the privilege of Western Europe’s superior races). Art is no longer solely the product of high intellectual and scientific cultures. Primitive peoples also make it. And since everything in art is judged by quality and since quality cannot be measured, these artistic products by primitive peoples are formally as legitimate and good as those of the super-refined civilizations of Greece or of France. Astonished by African, pre-Columbian, or Indonesian statuary, anthropologists and archeologists soon succeeded in convincing art historians and artists themselves as to the value of such revelations. It is, undoubtedly, a revelation of new formal organizations, pure, as pure as those who conceived the classic Western canons. Hence the profound revolutionary effect they have upon the sensibility of the best contemporary artists.

Simultaneously—and on its own—painting slowly arrived at a stalemate it was unable to overcome when, so as not to die by asphyxiation, it left the studio for the open air and came upon the open book of nature. Like a naughty child who runs away from home for the first time, Impressionism is dazzled by the miraculous properties of light. Hitherto apparently untouchable, the castle of academicism begins to crumble. Mandatory three-dimensionality is held in contempt. Young Impressionist painters feel happy because, now, they see before themselves an authentic new god to worship.

Psychology, in turn, as the youngest sister of the other sciences, is devoured by the ambition to expand the excessively timid horizons of classical or associationist routine. Like some new and unlimited continent, even richer and more mysterious than the American one, the Unconscious is discovered. Mechanical rationalism and its stunted fruit (abstract intellectualism) suffer a mortal blow. For the first time, then, the world of the arts is afforded the conditions to approach the preliminary albeit fundamental problem of its psychological origins, the subjective mechanicism of this activity before the finished work.

Even seemingly meaningless or unimportant acts that are practiced automatically—inconsequential movements, mistakes, scribbles, awkward drawings thoughtlessly made on paper—have become objects of interest and study. No gesture, word, or human act would ever again escape the field of psychological investigation. It was discovered that, beyond the express, apparently formal meaning of man’s actions and words there might be another, truer hidden meaning. The congenital unity of the human race was confirmed anew.

Surprisingly, a resemblance was noted between works by the coarse, anonymous men of one people and the simple folk of other peoples. A native ingenuity common to all these anonymous creators illuminated their works, whether of an artisanal nature or more disinterested or mystical, such as the representation of the image of an Indian god. This natural ingenuity was like an emotional password allowing entry into everywhere, because one felt in it an obvious manifestation of the poetic order (which is universal). Kinship between the arts of various primitive peoples and similar manifestations in children the world over have long been noted.

The newly born modern art movement, like a river at high tide that, throughout its tumultuous course, takes possession of all the objects and all the achievements that humanity has accumulated within the domain of disinterested expression, has lost its residual remains of abstract intellectualism in these latest universal acquisitions.

This marks the emergence of teams of so-called “moderns,” which have been succeeding one another for generations. Yet, even as they presented themselves to the public, they were received with a fierce hostility, with derision and hearty laughter, contempt and hatred. They were immediately identified as savages or madmen or simply pointed at as mystifiers. But their works came to speak for themselves; little by little they stood out to the eyes of a still-traumatized public, like echoes of intentionally ignored pre-Renaissance art, thanks to the reversal of aesthetic values that triumphant academicism imposed upon the world. Thus, they once again took up the great, true, living artistic vein that runs through the centuries and was interrupted by mannerism and post-Renaissance decadence. The result of all this was the elaboration of a new concept of art, which was nothing more than the rediscovery of artistic sentiment in its purity, so transparent in the work of the primitive anonymous artists.

This evolution or revolution of values is well expressed by André Lhote, who, aside from being a painter, is one of the soundest theoreticians in contemporary art. Among others, he was able to mark the difference in attitude of the modern artist compared to Impressionist, Renaissance, and primitive artists. In creating, the latter obeyed the sacred scriptures and their perspective; their order of things was supernatural, religious. They placed objects within a transcendental hierarchy that was in no way realistic. The Renaissance artist invented linear, geometric perspective, and—because he created within the exterior world—he came to organize it according to its optical illusions. The Impressionist constructs his world (rather, his detail of the world) according to an immediate, purely perceptual perspective as a consequence of light and color. Finally, the modern artist—who understands the trick of Italian perspective but no longer possesses the mystical simplicity of the primitive artist nor shows himself to be passive before the Impressionist’s play of natural light—refashions perspective. It is a new perspective, which Lhote calls affective in order to signify that it may no longer be reduced to any exterior formula, for the transformation that the creator artist imposes upon the natural relationship between objects obeys only—and must only obey—the rhythm of poetry, the rhythm of form.

To render even more sensitively and powerfully the contrast in attitude between an imitator of the Renaissance artist and that of the modern artist, it is useful to compare a definition of painting given by seventeenth-century French academicians with those of a Parisian modernist artist-theorist. In the seventeenth century, a painting was a “flat surface covered in lighter or darker hues that imitate the relief of objects and create the illusion of depth.” In Maurice Denis’s appropriation of the old Gothic formula of the primitives, a painting is “a flat surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order.”2Maurice Denis (published under the pen name Pierre Louis), “Définition du Néo-traditionnisme,” Art et critique 65/66 (1890): 540–42. Quoted in Henri Dorra, ed., Symbolist Art Theories: A Critical Anthology (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), p. 235.

In 1672 the French Royal Academy’s notion of painting was thus defined by one of its academicians: “An art that, by means of forms and colors, imitates, upon a flat surface, all the objects that appear to the sense of sight.” In the following session of the same Academy, in the same year, another member replied: “I do not know, gentlemen, whether it is possible to believe that the painter should strive for any purpose other than the imitation of beautiful and perfect nature. Should he pursue something chimeric and invisible? It is clear that the painter’s most beautiful quality is to be the imitator of perfect nature, for it is impossible for man to go beyond this.”

Yet more than two hundred years later, [Paul] Gauguin, for instance, did not think so, and wrote: “God took a little clay in his hands and made every known thing. An artist, in turn (if he really wants to produce a work of divine creation), must not copy nature but take the natural elements and create a new element.”3Paul Gauguin, The Writings of a Savage, ed. Daniel Guérin, trans. Eleanor Levieux (Da Capo: New York, 1996), p. 67. These conflicting concepts prove the impossibility of understanding artistic activity itself, let alone its intrinsic purpose, without brutally severing ties with the prejudices and conventions of academicism.

“I should be in despair if my figures were good,” wrote [Vincent] van Gogh, for “I don’t want them to be academically correct.”4Vincent van Gogh, letter to Theo van Gogh, July 1885, in The Letters of Vincent Van Gogh, ed. Ronald de Leeuw, trans. Arnold Pomerans (London: Penguin Books, 1997), p. 306. He declared emphatically, “I long most of all to learn how to produce those very inaccuracies, those very aberrations, reworkings, transformations of reality, as may turn it into, well—a lie if you like—but truer than the literal truth.”5Vincent van Gogh, letter to Theo van Gogh, July 1885, in The Letters of Vincent Van Gogh, ed. Ronald de Leeuw, trans. Arnold Pomerans (London: Penguin Books, 1997), pp. 306–07.

Therefore, artistic activity is something that does not depend upon stratified laws, the fruit of experience of a single age in the history of art’s evolution. This activity extends to all human beings and is no longer the exclusive occupation of a specialized brotherhood that requires a diploma for access. Art’s will manifests itself in any man in our land, regardless of his meridian, be he Papuan or cafuzo,6Cafuzo is a term used for Brazilians who have Indian-African mixed racial background. Brazilian or Russian, black or yellow, lettered or illiterate, balanced or unbalanced.

Artistic appeal is so irreducible that even [Charles] Baudelaire intuited that every child is an artist, or at least has the capacity to be a true poet or painter thanks to the freshness of his senses. “The child sees everything in a state of newness; he is always drunk. Nothing more resembles what we call inspiration than the delight with which a child absorbs form and color. . . . The man of genius has sound nerves, while those of the child are weak. With the one, Reason has taken up a considerable position; with the other, Sensibility is almost the whole being. But genius is nothing more nor less than childhood recovered at will.”7Charles Baudelaire, The Painter of Modern Life and Other Essays, trans. and ed. Jonathan Mayne (London: Phaidon, 1964), p. 8. Italics in original. To the great poet, the artist of genius was “a man-child,” that is, “a man who is never for a moment without the genius of childhood.”8Ibid.

Indeed, for Baudelaire—he who understood his his trade so well—genius is a state of childhood, and inspiration tends to intensify with spontaneous, vital, unconscious forces that accumulate—so to speak—in the tender, open pores of children. The discovery and exploration of the unconscious came as if to confirm the poet’s intuitions.

Thus man draws a little closer to the mysterious sources of artistic creation. Pictorial art is no longer a way to imitate nature, to represent external reality, or, as Monsieur Blanchard (the same French academician of 1672) would have it, to “bestow roundness to the bodies that are represented upon a flat surface.” This art is no longer the science of trompe l’oeil! In any form, whether large or small, profound or decorative, mere elementary sketch or formless blot, to be considered art is initially a matter of emotion and sensation or, in [Georges] Braque’s laconic formula, “sensation and revelation.”9“Unceasingly we run after our destiny. Sensation. Revelation.” Georges Braque, “Notebooks 1947–1955,” in Georges Braque’s Illustrated Notebooks, 1917–1955, trans. Stanley Appelbaum (New York: Dover Publications, [1948] 1971). It is not only artists and poets such as Baudelaire and Van Gogh who have intuition or—rather—the so-to-speak physical sentiment of the unconscious process of creation.

Defining it in terms of his own experience, Van Gogh spoke of his “terrible lucidity at moments,” in which, according to his confession, “I am not conscious of myself anymore, and the pictures come to me as in a dream.”10Vincent van Gogh, letter to Theo van Gogh, September 1888, in The Complete Letters of Vincent Van Gogh: With Reproductions of All the Drawings in the Correspondence, vol. 3 (Greenwich, Conn.: New York Graphic Society, 1958), p. 58. The more objective modern psychologists—not the followers of [Sigmund] Freud or [Carl] Jung, but the fervent followers of behavioral psychology such as Henri Wallon—arrived at identical conclusions. As a general observation, they admit that, “Whereas conscience is mistress of the terrain, vain are the efforts of wise men and men of letters to accomplish the work that consumes them.” According to them, consciousness must “abdicate,” “give in to forgetting,” that is, to the subconscious.

In all mental domains, therefore, the problem of creation would consist of freeing the creators, who would forget previously established mental associations, already chained automatically to certain formulas. Yet this does not explain why a child is freer from these tyrannical associations than an adult, and the mentally abnormal man more so than the average one. “Only when the creators free themselves from an individuality that rejects any new combination,” the same illustrious professor admits, “shall they be able to contribute to a new intuition” and (we would say) with much stronger reason to any new image.

The normal observer or scientist must keep to examination and to reflection in order to avoid consciousness from dispersing. In light of this, the objective psychologists sound the alarm and point to “the unstable subjects whose illness consists precisely in allowing consciousness to abandon itself to any and all impression that solicits it.” Now, this examination and reflection act precisely in the sense of rendering consciousness insensitive to what these psychologists call “aberrant stimuli”; on the contrary, the observer is incapable of following the course of his perceptions and thoughts.

But for the artist—neither an observer nor a scientist—the advice is no good; it is not up to him, according to the logic of true art, to follow, as an external observer, the course of his own perceptions and thoughts in order to control them. He is not an observer. He is a creator, a being with emotions that demand formal expression. Wherever he may be, his task is to seek out that new intuition of which the scientist spoke, the new image. Consequently, for the artist there are no aberrant stimuli (rather, there is the hackneyed “Aeolian harp” of rhetoric or old Hugo’s “sonorous echo”).

Still, for the same psychologist, “A sufficient adaptation to the environment allows us to perceive only the objective, conscious side of the life of the mind. As long as it exactly represents our intimate aspirations vis-à-vis the exterior world, this will suffice to eclipse them totally.”

Now there can be no manifestation of artistic nature—and much less any creative appeal—with these eclipsed or absorbed intimate apsirations that come out of a “sufficient adaptation to the environment.” However, if the “objective and conscious face of psychic life” is insufficient to contain or express the “intimate aspirations,” as “anomalies,” the various “perversions” according to the “needs of existence” (also according to the psychologist’s terminology), the influx “of subjective influences” necessarily reappears. These intimate aspirations are evidently impenetrable “to the objective and conscious face of psychological life”; rather, they constitute the other irreducible face of the same life, the one that never ceases to demand expression from us, just as, on another level, another face—the inscrutable side of the moon—never ceases to torment our eternal curiosity.

According to another teaching of this very psychology, “for every representation that flutters in our consciousness and pursues us, a tendency develops to externalize it, to place it before us, to find for it a subject outside of us.” Enfeebled consciousness tends to allow representations that obsessively inhabit the mind to escape. This is when that tendency to externalize emerges, setting these representations outside consciousness itself, as if they belonged to a foreign subject. In children, and above all in mentally disturbed personalities, this representation is profoundly internalized; for this very reason, the need to externalize may become unbearable. Even when it is simply therapeutic—as in the case of the artistic activity of the exhibitors Who currently interest us—this activity may lead the obsessions to be sublimated, just as one might vanquish an enemy—by giving them formal expression. Of the process of elaboration, the document of externalization remains liable to being isolated and appreciated as intrinsic artistic expression.

Baudelaire spoke of “congestion” to express his concept of inspiration; momentarily in the grip of a “terrible lucidity,” Van Gogh enters it like a dream and is no longer able to feel himself. According to Wallon, Jean-Jacques Rousseau finds himself in a similar state after a fainting spell. Describing his sensations, Rousseau wrote: “In that instant I was born into life, and it seemed to me as if I was filling all the things I saw with my frail existence.”11Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Reveries of the Solitary Walker, trans. Russell Goulbourne (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 14. Thus, the decline of conscious activity seems to lead parts of ourselves that we habitually forget are essentially ours to unmoor themselves from us. The body is therefore a sort of exterior field of sensations, which direct and organize themselves indpendently from us as if taking place at a regular distance from our very self. Consciousness is no longer able to oppose itself to these sensations, which are eventually mistaken with environmental reality itself. The same psychologist concluded that consciousness has lost the power of objectifying the representations that touch it.

This diffusion of states of consciousness in space comes about when there is a blurring of the lines, which the normal activity of consciousness never ceases to draw, between what distiguishes “I” from “not I,” between subject and object: it is more or less what occurs during a fainting spell.

The diffusion of consciousness in space . . .

Would such not be the case with these schizophrenics, these already entirely dissociated personalities such as that of D, in the exhibition catalogue, the author of these enigmatic watercolors to which he has given strange, invented names such as Flausi-Flausi, Feérica [Magical], etc.? They are adult beings enveloped by an insurmountable isolation, no longer possessing the power to coordinate the representations that touch consciousness itself or distinguish their sensations from the images and reflections of environmental reality.

He is no longer the creator of Flausi-Flausi; he is dispersed in air, in things, as it were; he is an object endowed with antennae, a strange living being that no longer inhabits this world of ours; a harp, a triangle of sound; these colored lines he weaves construct a sort of circuit between vegetable and animal, with the consistency of damp fibers like those of the trunk of a banana tree. The result is a mesh, a new framework for purposes as yet unclear; it might be the unfinished structure of a fantastical dirigible, the covering of which should have been swept away by the winds of space. Whether formless or uncoordinated, all this nevertheless possesses an oddly musical quality, an abstract counterpoint in which the melodic lines of the dissociated personality still cross one another yet are no longer coordinated, no longer fixed in a group with a beginning and an end. Some of them point to the idea of a star machine, a celestial body, a passing meteorite. None of this precludes the fact that, within the chaotic mesh, admirable details may reveal themselves to the attentive gaze, the sweetest of profiles may appear like precise hallucinations or vaguely suggested dreams and symbolic signs to satisfy the curiosity of the most implacable analyst.

In passing, it must be said that what is lacking in these embryonic samples of art that we have here—the emotional raw material of formal creation—is productive will; that terrible, almost inhuman will that vanquished inner chaos itself in Van Gogh, imposing a formal organization and disciplining its explosive forces, subordinating everything to the final cosmic order necessary to creation.

Even in the most artistic—in the technical sense—of these personalities now exhibited before us, we may notice the absence of this formal resistance, the soul of the composition; however, it is what most differentiates the drawing or painting of a psychopathic personality or a child from those of a still conscious artist. In them a subjective confidence, an explosion of the affected self and the child’s cosmic amazement before the eternally new spectacle, is predominant.

There is in these drawings and documents exhibited by the Centro Psiquiátrico Nacional—which by so doing performs an inestmable service to Brazilian culture—a clear contrast between the joyous, spirited, playful minds evident in the images produced by the hands of minors, and the darker, more melancholy humor of those produced by the adults. Let us examine, for instance, Passeata [Protest March] or A’s cold Paisagem Abismal [Abismal landscape] and the minor D’s Cabritinho [Little goat] or Menino com o Bodoque [Boy with slingshot]; compare the bitter, hallucinated expression of Autin’s figures or the pungent, perverse, sickly romanticism of the author of the veritable drama in figures that is Minha Vida [My life] to the young O’s doodles or farmyard chicks and nativity scenes.

In the end, what is art, from the emotional point of view, other than the language of unconscious forces that act within us? In turn, might not the visual arts be reductions of sentiments and aspirations that, even if they might become conscious, cannot be translated into words, according to Maria Petrie, that admirable pedagogue of the soul and of aesthetics? It is upon exactly this that modern educators of her kind base themselves. What they propose is to make use of art as a means by which to arrive at the harmony of the subconscious and to a better organization of human emotions. They request that “this grammar of a language able to express such important and subtle things” be taught to whoever wishes to learn it, in order that it may cease to be “the secet code of an elite.” Without this, it would once again become the instrument of a brotherhood more cloistered than the academic one, and more dangerous still because it is affective and possesses strange powers.

It is through this language that we learn the unconscious work of the mind that manifests itself in inspiration, that is, through the sudden projection of some thing or message in the field of consciousness, according to the vivid definition of the English educator. According to Petrie’s definition, inspiration is knowledge, cognition by means of emotion rather than by means of intellect.

This is how we define the whole of one of the most signifcant branches of modern art, that of the family of subjective artists, the principal strain of which is represented by Surrealism. Let us not forget that one of the guiding principles of Surrealism is a condemnation of the external model (which is replaced by the incessant search for an interior model). Revelations could be found in dreams and in the symbolism of the unconscious, and the principal means of capturing subconscious images would be psychological automatism, whether of verbal expression, in poetry, or visual expression, in painting and sculpture.

Painting speaks a new language: through it new possibilities for contact with other beings are established—a contact that will take place precisely within those regions in which the spoken word cannot penetrate or cannot be called to intervene.

Thus by felicitous coincidence, as currently considered by psychologists and artists and in light of these primary, elementary manifestations—the inconsequential bleatings of a creation that shall never come to be—the artistic phenomenon must be understood in a broader sense than it has been. This broader sense will allow it to reach its extremes, to catch up with simple, disinterested, lucid activity, in other words, that of the game with various materials that technology provides.

In this sense, even the scribbles of children and the mentally diminished fundamentally possess the same nature as the works of the world’s great artists, conforming to an identical psychological process of creative elaboration. In all of these multiple and diverse manifestations, to greater or lesser degrees of intensity, what is essentially dealt with is nothing less than a bestowing of symbolic form (but form nonetheless) onto the feelings and images of the deep self.

Each individual is a separate psychological system, as well as a potentially malleable and formal orgnization. Psychological normality and abnormality are the conventional terms of quantitative science. In the domain of art, however, they cease to have any decisive meaning. Here, the boundaries between things are fainter, harder to precisely define than in any other domain of mental activity. The case of Van Gogh is conclusive: he was insane; yet some of his finest work was done while he was hospitalized. And do we not know other, equally illustrious cases in the field of literature such as those of [August] Strindberg and [Friedrich] Hölderlin? And, in England, at the beginning of the Victorian era, did we not have the pathetic case of the great medievalist William Blake? Doctors and psychiatrists tell us it is common to recognize accentuated manifestations and traits of schizophrenia and manic depression in so-called normal types.

From the perspective of the senses and the imagination, an intellectually disabled child or a mentally ill adolescent is, generally, quite normal; this is why they are able to produce authentic artistic manfestations and achievements. Their creative or imaginative appeal never disappears. On the contrary, they may oftentimes become more intense, urgent, and irrepressible, for that will be the only vehicle they trust to communicate with the exterior, for real communication, that is, from soul to soul.

In literary works, the creative process may be more rational because it does not dispense with but actually requires—to a certain degree—the contribution of intellectual concepts. Their dependency upon public participation is therefore greater. It is, however, less acessible to the child and the more mentally challenged.

For the mentally impaired and for children, for innocents of every sort, the art forms that require the least intellectual or conscious effort are the most accessible. This is not so much the case with music, in spite of the rhythmic element, which is instinctive, for children are not very sensitive to melody and harmony. In effect, these require a power of continuity and organization that escapes beings with a more hesitant control of consciousness.

Under these conditions, the visual arts are closest to the sensibility of children or the simple-minded. According to Petrie, they participate in the cosmic principles inherent to space, such as two- and three-dimensional form, volume, mass, weight; in those same principles inherent to light: color, shadows, hues; and they deal with matter that can be acted upon, such as clay, stone, wood, paper, charcoal, etc.

Creative activity essentially repeats unconsciously the ongoing re-creation of the miracle of life among organisms, and that is what gives such exultant power to the work of pure creation. Hence artist and educator Maria Petrie’s hypothesis that nature, in its attempt to lead our mental and psychological growth to develop harmoniously and in step with physical growth, has imposed its own laws upon actual artistic phenomena, so that men might finally recognize them and surrender to them. Thereby the same phenomena would take on the nature of a vital need, for it would be no more than a transposition onto the human plane of the laws of cosmic creation. This vitality, or form of vitality, is more urgent and irreducible when it identifies, defines, and expresses itself through those cosmic principles that rule things—“vitamins of the soul,” to use Petrie’s expression—that is, light, color, weight, rhythm, form, movement, and proportion. Art would be made according to the same principles that rule the incessant creation of the universe and its functional mechanism. It does not repeat or copy nature. Instead, it obeys the same rules; it transposes them to the plane of conscious (that is, human) creation. Thus, an artist is an individual who elevates himself to the category of universal architect, as the poor wretch Gauguin would have it.

At least in part, the discovery of the unconscious reveals to us the origins of artistic creation. The images and the life elaborated in it are the most genuine raw materials of the work of art. The latter manifests itself with or without the control of consciousness. It dispenses with the external contribution of the intellect. It belongs purely to the domain of the sensations that transmute themselves, by true miracle, into a harmony of formally structured emotions.

The visual arts may even dispense with those organs most indispensable to representation of the exterior world. Modeling may cease to be a visual art, given that through inner, haptic vision, the blind man, endowed with a sense of rhythm, is able to create plasticity.

To this end, it suffices that he combine the intuitions of touch with the divine sense of rhythm. Married to a sense of rhythm, this highly developed sense of touch allows a blind man to mold clay or mud and create inspired figures of profound formal visuality, of extraordinarily harmonic lines and planes. We already know of examples of these modelings through touch alone—the work of a blind man—which recall the formal organization of Lucas Cranach’s figures.

Thus we have proof that these arts have no need of external visual representation. Indeed, the less they are subjected to realistic conventions and intellectual prejudices the more profound they are. A pure creation of the mind, the work leaves the unconscious or nothingness with the heat of things that are born to life, exuding joy, pain, sensitivity, in a system of emotions that—in turn—revigorates men with its spiritual vitamins, touching them with the grace of comprehending and the emanations of the world of forms.

Painting and sculpture—the arts in general—are techniques that must be learned as one learns to read and write, to sew, to cook, to weave. Their effects can make themselves felt even upon the mentally ill, whether by curing them or giving them hope, or by enticing them to once more come outside into our brutal, ugly world with messages, occasionally decipherable, that shine, devastating and fleeting, like flashes. There are no barriers—nor could there be, in fact—to the enchanted world of forms; there is no standing in line to enter its arena, which belongs to no one and is common to all men without exception. Humanity is happy when all of them, initiated and without inhibitions, are able to penetrate this magical field! Entry is available to everyone.

The arts are surely not an unattainable exception. There is no education of the emotions, in the sense of an intellectual education, a social education, or education in other technqiues for living. The earliest manifestations of the emotions appear at a very young age, and they do not respect limits, obstacles, prejudices, regulations, or even “states of consciousness.”

Art begins with a child’s earliest doodles and is present wherever men make use of hand and eye—of their senses and their hearts simultaneously—to bestow form unto anything that is not for immediate use, moved by the simple pleasure of making something, or even merely to express unconscious impulses. This is the case of the less adapted, such as these highly sensitive children and adults who now surround us with their invisible presence. The only means still left to them for communicating with us in depth (which is to say humanly), for signaling to us, is through these modest emotional expressions transferred onto paper and which, being of an obviously artistic nature, have been the object of our present discussion.

“Arte, necessidade vital,” talk given at the closing conference of the exhibition organized by the Centro Psiquiátrico Nacional, with support from the Associação dos Artistas Brasileiros at the ABI, March 31, 1947. In Correio da manhã (Rio de Janeiro), April 13 and 21, 1947.

Environmental Art, Postmodern Art, Hélio Oiticica

This 1966 essay is renowned for its early use of the term “postmodern.” Unlike later theorizations, the Brazilian critic Mário Pedrosa deploys the concept to discuss how immersive environments replace distanced visual perception in the artworks of Hélio Oiticica and Lygia Clark. New attention to the essay—where the text is interpreted as an alternate theoretical point of departure—has instigated a rethinking of the relationship between art and broader cultural shifts in the postwar period in Brazil and beyond.

Now that we have arrived at the end of what has been called “modern art,” inaugurated by Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, and inspired by the (then) recent discovery of African art, criteria for appreciation are no longer the same as the ones established since then, based as they were on the Cubist experiment. By now, we have entered another cycle, one that is no longer purely artistic, but cultural, radically different from the preceding one and begun (shall we say?) by Pop art. I would call this new cycle of antiart “postmodern art.”

(In passing, let us say that, this time around, Brazil participates not as a modest follower, but as a leader. In many regards, the young exponents of the old Concretism and especially of Neoconcretism (as led by Lygia Clark) have foreshadowed the Op and even Pop art movements. Hélio Oiticica was the youngest of the group.)

In the apprenticeship phase and in the exercise of “modern art,” the natural virtuality, the extreme plasticity of perception of the new being explored by the artists was subordinated, disciplined, and contained by the exaltation and the hegemony of intrinsically formal values. Nowadays, in this phase of art in the situation of antiart, of “postmodern art,” the reverse takes place: formal values per se tend to be absorbed by the malleability of perceptive and situational structures. As a psychological phenomenon, it is perfectly clear that the malleability of perception increases under the influence of emotion and affective states. Like the classical modernists, today’s avant-garde artists do not avoid this influence and certainly do not seek it out deliberately, as did the romantic subjectivists of “abstract” “or lyrical” Expressionism.” Expressiveness in itself is of no interest to the contemporary avant-garde. On the contrary, it fears hermetic individual subjectivism most of all—hence the inherent objectivity of Pop and Op art (in the United States). Even the “new figuration” (in which the remains of subjectivism have aligned themselves) aspires above all else to narrate or to spread a collective message about myth and, when the message is an individual one, to use humor.

As early as 1959, when throughout the world the romantic vogue for Art Informel and tachisme predominated, the young Oiticica, indifferent to fashion, had given up painting in order to forge his first unusual, violently and frankly monochromatic object—or relief—in space. Having naturally broken away from the gratuitousness of formal values that are rare among today’s avant-garde artists, he remains faithful to those values in the structural rigor of his objects, the discipline of his forms, the sumptuousness of his color and material combinations—in short, for the purity of his creations. He wants everything to be beautiful, impeccably pure, and intractably precious, like a Matisse in the splendor of his art of “luxury, calm, and voluptuousness.” The Baudelaire of Flowers of Evil may be the distant godfather of this aristocratic adolescent who is a passista12 A samba school dancer; from the Portuguese word for “passos,” meaning “steps.” for the Mangueira13Grêmio Recreativo Escola de Samba Estação Primeira de Mangueira, founded in 1928 on Mangueira Hill in Rio de Janeiro. [samba school]—albeit without the poéte maudit’s Christian sense of sin. His Concretist apprenticeship almost prevented him from reaching the vernal, ingenuous stage of the first experiment. His expression takes on an extremely individualist character and, at the same time, goes all the way to pure sensorial exaltation without, however, achieving the psychological threshold itself, where the transition to the image, to the sign, to emotion and to consciousness takes place. He cut this transition short. But his behavior suddenly changed: one day, he left his ivory tower—his studio—to become part of the Estação Primeira, where his painful and serious popular initiation took place at the foot of Mangueira Hill, a carioca myth. Even as he surrendered to a veritable rite of initiation, he nonetheless carried his unrepentant aesthetic nonconformity with him to the samba in the eternally hardcore spaces of Mangueira and environs.

He left at home the spatial reliefs and Núcleos [Nuclei], the continuation of an experiment with color he called Penetravél [Penetrable]—a construction in wood with sliding doors in which the subject might seclude himself inside color.

Color invaded him. He made physical contact with color; he pondered, touched, walked on, breathed color. As in Clark’s Bichos [Animals] experience, the spectator ceased to be a passive contemplator in order to become attracted to an action that lay within the artist’s cogitations rather than within the scope of his own conventional, everyday considerations, and participated in them, communicating through gesture and action. This is what the avant-garde artists of the world want nowadays and it is really the secret driving force behind “happenings.” The Núcleos are pierced structures, suspended panels of colored wood that trace a path beneath a quadrilateral, canopy-like ceiling. Color is no longer locked away; the surrounding space is aflame with violent yellow or orange color-substances that have been unloosed, seizing the environment and responding to one another in space, as flesh, too, is colored, and dresses and cloth are inflamed, and their reverberations touch things. The incandescent environment burns, the atmosphere is one of decorative over-refinement that is simultaneously aristocratic, slightly plebeian, and perverse. The violent color and light occasionally evoke van Gogh’s nocturnal billiards room, in which those colors that symbolized the “terrible passions of humanity”14Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, September 3, 1888, in Van Gogh: A Self-Portrait, Letters Revealing His Life as a Painter, ed. W.H. Auden (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1963), p. 319. reverberated for him.

Oiticica called his art environmental. Indeed, that is what it is. Nothing about it is isolated. There is no single artwork that can be appreciated in itself, like a picture.

The sensorial perceptual whole dominates. Within it, the artist has created a “hierarchy of orders”—Relevos [Reliefs], Núcleos, Bólides15According to Oiticica, “BÓLIDES were not actually an inaugurated art form: they are the seed or, better yet, the egg of all future environmental projects.” Hélio Oiticica, O objeto na arte brasileira nos anos 60. Written in New York, December 5, 1977, for the catalogue O objeto na arte brasil nos anos 60 (São Paulo: Fundação Armando Alvares Penteado, 1978). (boxes), and capes, banners, tents (Parangolés)16According to Hélio Oiticica, “The discovery of what I call ‘parangolé’ signals a crucial point and defines a specific position within the theoretical progression of all my experiments with color-structure in space, especially insofar as it refers to a new definition of what the ‘plastic object’ (or, in other words, the work) may be within this same experience. . . . The word here serves the same purpose it did for Schwitters, for example, who invented ‘Merz’ and its derivates (‘Merzbau’, etc.) to define a specifically experimental position [that is] basic to any theoretical or experiential comprehension of his entire work.” Helio Oiticica, “Bases fundamentais para uma definição do ‘Parangolé,’” Opinão 65 (Rio de Janeiro: Museu de Arte Moderna, 1965). —“all directed toward the creation of an environmental world.” It was during his initiation in samba that the artist moved from the purity of visual experience to an experiment in touch, in movement, in the sensual fruition of materials in which the entire body—previously reduced in the distant aristocracy of visuality—makes its entrance as a total source of sensoriality. In the wooden boxes that open like pigeonholes from which an inner light hints at other impressions, opening up perspectives through movable panels, drawers that open to reveal earth or colored powder, etc., the transition from predominantly visual impressions to the domain of haptic or tactile ones becomes evident. The simultaneous contrast of colors moves on to successive contrasts of contact, of friction between solids and liquids, hot and cold, smooth and creased, rough and soft, porous and dense. Wrinkled colored mesh springs from within the boxes like entrails, drawers are filled with powders and then glass containers, the earliest of which contain reductions of color to pure pigment. A variety of materials succeed one another: crushed brick, red lead oxide, earth, pigments, plastic, mesh, coal, water, ani¬line, crushed seashells. Mirrors serve as bases for Nucléos or create further spatial dimensions within the boxes. Like artificial flowers, absurdly precious and lush yellow and green porous meshes emerge from the neck of a whimsically shaped bottle (of the type that belongs to a liqueur service) filled with transparent green liquid. It is an unconscious challenge to the refined taste of aesthetes. He has called this unusual decorative vase Homenagem a Mondrian Tribute to Mondrian. A flask sits upon a table amid boxes, glass containers, nuclei, and capes—a Louis XV-like pretense of luxury within a suburban interior. One of the most beautiful and astonishing boxes, its interior filled with variegated circumvolutions (meshes), is illuminated by neon light. There is enormous variety in these box and glass Bólides. No longer part of the macrocosm, everything now takes place inside these objects; it is as if they had been touched by some strange experience.

One might say that the artist transmits the message of rigor, luxury, and exaltation that vision once gave us into the occasionally gloved hands that grope and plunge into powder, into coal, into shells. Thus he has come full circle around the entire sensorial–tactile–motile spectrum. The ambiance is one of virtual, sensory saturation.

For the first time, the artist finds himself face to face with another reality—the world of awareness, of states of mind, the world of values. All things must now accommodate meaningful behavior. Indeed, the pure, raw sensorial totality so deliberately sought after and so decisively important to Oiticica’s art is finally exuded through transcendence into another environment. In it the artist—sensorial machine absolute—stumbles, vanquished by man, convulsively confined by the soiled passions of ego and the tragic dialectic of social encounter. The symbiosis of this extreme, radical aesthetic refinement therefore takes place with an extreme psychological radicalism that involves the entire personality. The Luciferian sin of aesthetic nonconformity and the individual sin of psychological nonconformity are fused. The mediator of this symbiosis of two Manichaean nonconformisms was the Mangueira samba school.

The expression of this absolute nonconformity is his “Homenagem a Cara de Cavalo” [Tribute to “Cara de Cavalo”], a veritable monument of authentically pathetic beauty in which formal values are finally not supreme. An open box without a lid, modestly covered by mesh that must be lifted to reveal the bottom, its inner walls are lined with reproductions of a photograph that appeared in the newspapers of the day; in them, [the outlaw] “Cara de Cavalo”17“I knew Cara de Cavalo personally and I can say he was my friend although—to society—he was public enemy number one, wanted for bold crimes and robberies—what perplexed me then was the contrast between what I knew of him as a friend, someone to whom I talked within the context of everyday life, as one might to anyone else, and the image created by society, or the way he behaved in society and any other place. This tribute is an anarchic attitude toward all kinds of armed forces: police, army, etc. I make protest poems (in capes and boxes) that have more of a social meaning, but this one (for Cara de Cavalo) reflects an important ethical moment that was decisive for me, because it reflects an individual outrage against every type of social conditioning. In other words: violence is justified as a means for revolt but never as a means of oppression.” In: Hélio Oiticica, “Material para catálogo” [Whitechapel Gallery, London, 1969], typescript, partially published in the exhibition catalogue for the artist’s show at London’s Whitechapel Gallery from February 25 to April 6, 1969. See also, by the author, O herói anti-herói e o anti-herói anônimo, March 25, 1968. appears lying on the ground, his face riddled with bullets, his arms open, as if crucified. What absorbs the artist here is emotional content, now unequivocally worded. In an earlier Bólide, thought and emotion had overflowed its (always-magnificent) decorative and sensorial carapace to become an explicit love poem hidden inside it upon a blue cushion. Beauty, sin, outrage, and love give this young man’s art an emphasis that is new to Brazilian art. There is no point in moral reprimands. If you are looking for a precedent, perhaps it is this: Hélio is the grandson of an anarchist.18Hélio Oiticica’s grandfather, José Rodrigues Leite Oiticica was a philologist, poet, translator, and editor of the anarchist newspaper Ação direta. He lectured on Portuguese philology at the University of Hamburg in 1929. Hélio’s father, José Oiticica Filho, an engineer, professor, and photographer, received a Guggenheim Foundation grant in 1947, and worked at the United States National Museum-Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C., in 1948.

Originally published as “Arte ambiental, arte pós-moderna, Hélio Oiticica,” Correio da manhã (Rio de Janeiro), June 26, 1966.

The New MAM Will Consist of Five Museums

In this 1978 text, the influential Brazilian critic Mário Pedrosa lays out a plan for a museum of modern art that is very different from other institutions bearing that name. Acknowledging the relationships of modern art to folk art, indigenous art, African art, and art created by children and the mentally ill, he proposes a new museum called the Museum of Origins (Museum das Origens) to house all of these forms of expression within one institutional frame.

During a meeting of the Committee for the Reconstruction of the MAM [Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro] held yesterday at the Escola de Artes Visuais, in Parque Lage, art critic Mario Pedrosa suggested reorganizing the museum according to a new structure composed of five independent albeit organic museums: the Museum of Black People and the Museum of Folk Arts [sic].

He said: All modern art has been inspired by the art of peripheral peoples, so that nothing could be more appropriate than for the Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro to display this art we possess in abundance alongside a collection of contemporary Brazilian and Latin American art.

In his proposition, Mario Pedrosa gives a succinct explanation regarding the founding of the Museum of Origins:

As a result of the MAM’s total destruction by fire,19 A fire in the Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro, in 1978, signaled a tragic moment in the museum’s history and for Brazilian cultural overall. It happened during a retrospective exhibition of work by Uruguayan artist Joaquín Torres Garcia (1874–1949) and the exhibition Geometria Sensível (Sensitive geometry), organized by Roberto Pontual. It destroyed the majority of the works in the exhibition, as well as others from the museum’s collections that were on display. it is imperative that some logical conclusion be drawn from the catastrophe: the MAM is gone. With Niomar Moniz Sodré Bittencourt20Niomar Muniz Sodré Bittencourt (1916–2003) was the executive director of the Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro throughout the 1950s. leading the group that so generously applied itself to the work of creating it is no longer in any condition to start the task anew. The situation has changed; the times have changed; the philosophy, even the ideology that inspired those who made the museum more than twenty years ago has changed; hence the need to summon others and the State to create a congeneric establishment with other purposes. The time of purely private patronage has passed. Even in the United States, New York’s Museum of Modern Art itself already resorts to substantial assistance from the state. Therefore we propose that the reconstruction be undertaken with the state’s assistance and collaboration. We propose that a public or semipublic foundation be constructed, but that, along the lines of others that exist in this country, it should retain its full autonomy. Specialists in the subject guarantee its full viability.

What follows is the text read by Mario Pedrosa:

The founding of the Museum of Origins anticipates the establishment of five museums: the Museum of the Indian; the Museum of Virgin Art (Museum of the Unconscious); the Museum of Modern Art; the Museum of Black People; and the Museum of Folk Arts.

These museums are all related although they are independent from one another. The Museum of the Indian already possesses its own structure, its own organization, certain resources, and an important collection, albeit no appropriate location.

The Museum of the Unconscious also has its own structure, organization, resources, and an excellent collection. Yet its installations are in precarious condition and even somewhat threatened. It is crucial that they be secured for the good of Brazilian and global culture. The Museum of Modern Art possesses magnificent headquarters and a location that can house the others, but only a small collection of works left over from the fire.

The foundation should be of a public or semi-public nature to ensure its permanence and solidity, particularly with regard to resources, although it should dispose of an autonomous organizational structure to guarantee a cultural and artistic orientation that is not only coherent and homogeneous but not subject to changes of orientation and administration, a consequence of extemporaneous and bureaucratic political interventions that are not wholly advisable.

A committee of competent, active professionals and a board of directors made up of eminent and representative personalities whose respectability is well-recognized in society will be responsible for the cultural and artistic orientation of the foundation and an efficient, trustworthy, and authorized administration.

The Museum of Modern Art must rebuild a collection that is first and foremost representative of Brazilian art, from the early Impressionism of [Eliseu] Visconti to generations that followed, with artists such as [Vitor] Brecheret, [Lasar] Segall, Tarsila [do Amaral], Anita Malfatti, [Emiliano] Di Cavalcanti, [Cândido] Portinari, [Alfredo] Volpi, [Osvaldo] Goeldi, and Lívio Abramo, and on to the younger artists of today. It should also contain Latin American rooms, with work by the Uruguayan [Joaquín] Torres Garcia and artists from Mexico, Argentina, Peru, Colombia, Venezuela, and Cuba, etc., as well as European rooms and North American rooms. There will be a room dedicated to Concrete art, one that corresponds to the MAM’s modern origins in Europe, in Brazil and in Argentina. A room dedicated to the Neo-Concrete art of Brazil, in addition to rooms for temporary exhibitions.

The Museum of Black People’s collection will be based on pieces brought from Africa and others made here in Brazil, especially for religious use.

The Museum of Folk Arts collection shall be made up of pieces collected throughout Brazil’s various regions, in the various types of artifacts such as pottery, wood, iron, tin, straw, etc.

Body of theoretical courses and practical apprenticeship at the MAM: visual arts, music, film, video tape, photography lab, graphic arts workshop, printmaking studio, joinery [cabinet-making], Moviola, etc.), and a few general subjects such as art history, cultural anthropology, as well as specialized sections on urban culture, rural communities, tribal communities, urban festivals, and Carnival.

Financial sources: a) state-owned companies; b) federal, state, or municipal budgets; c) private donations.

The MAM will generate income through its graphic arts workshop, joinery and printmaking studios, photography lab, editing room (Moviola), slides, silkscreen, etc.

Member contributions will be needed in order to maintain the foundation’s democratic and popular organization, along with public and private donations of permanent, temporary, and specialized natures.

Originally published as “O novo MAM terá cinco museus. É a proposta de Mario Pedrosa,” Jornal do Brasil, September 15, 1978.

The Machine, Calder, Léger, and Others

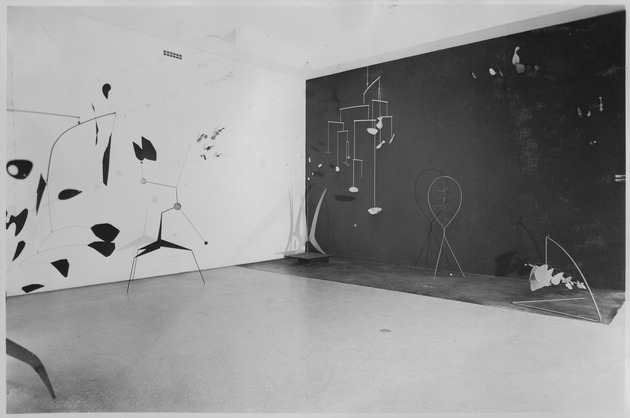

In this 1948 essay, available in English for the first time, the Brazilian critic Mário Pedrosa considers the machine, the quintessential industrial object, in dialectical relation to the modern work of art. Finding precedents in “primitive” and Byzantine arts, Pedrosa goes on to consider how the machine is stylized, repurposed, and mastered in the work of Fernand Léger and Alexander Calder. He declares the latter to be the preeminent American artist for his keen understanding of mechanical functions, which he applies towards the creation of artworks that for Pedrosa signify freedom from a functionalist, profit-driven culture. Pedrosa, who was a close friend of Calder and authored several texts devoted to his practice, first became taken with the artist’s work during a visit to the artist’s monographic exhibition at MoMA in 1943. The last in a series of essays by Pedrosa published on post, this text is the only one that is not included in Mário Pedrosa: Primary Documents (2015), which collects the key writings of the legendary Brazilian critic.

Were there any doubt that an aesthetic sense—or a sense of beauty, if you will—is an acquired thing, or was acquired as far back as the primitive ages through protracted intimacy with the instruments and tools of human labor, [Alexander] Calder would help us to dispel that doubt.

Indeed, he made use of the instruments and mechanical objects, of the gadgets that are so important to the everyday lives of Americans, in order to provide them with an unexpected fate.

First and foremost, he added to them a decorative sense that they did not already possess. By this utilitarian use of industrial tools, he ultimately follows the ancient procedure according to which all the artistic activities of the past originated.

The primitive almost never separates the everyday objects that he builds from their primarily utilitarian purpose. Yet when the savage, little by little—as he repeatedly embellished the form of his bow or of his oar, emphasizing a curve here or polishing a surface there—wound up making the instrument a work of art, one may conclude: the artist begins to emerge from the craftsman’s leftovers, which maintains itself within the strict limits of functionality.

Driven by the decorative instinct, the craftsman-savage oftentimes exceeds the utilitarian purpose and, through the formal elegance that he gives the bow or any other utensil, he renders it impractical for work. At this extreme point, either the craftsman retreats so as not to disrespect the fixed boundaries of functionality, or he engages in a different activity, the central concern of which will thenceforth be the creation of a new object that will be sufficient unto itself—abstract.

The craftsman becomes an artist.

Like so many other modern artists, Calder resorts to craftwork and makes use of modern industrial instruments. However, from the outset he gives them seemingly inconsequential purposes. Thus he imparts to mechanics a gratuitousness that it does not have, nor belongs to its nature. In so doing he transcends the very utilitarian civilization from which it comes.

In the foundry where he works, Calder naturally does not follow primitive man’s artisanal logic. On the contrary, in adopting the Surrealist procedure, he redirects the object from its specific or conventional destiny. The difference is that, with this, Sandy is not seeking out the anodyne, the bizarre, or the romantic, but simply creating a new object, a new form.

Calder the artificer, who soon lost his way, seduced as he was by the fleeting beauties of Abstraction, was condemned to be the most terrible violator of functional mechanics. In dialectical opposition to American civilization, based on business for the sake of business, on profit, he is, for this very reason, the artist most representative of the United States, as is—in the field of architecture—[Frank Lloyd] Wright who, in his old age and in spite of his glory, became the prototype of the artist who rebelled against the social milieu. It is precisely such an opposition that makes Calder an exponent of that culture, revealing what may be sane and liable to development within it.

When Calder discovered the disembodied beauty of “volumes, vectors and densities,”21Phrase taken from the title of Calder’s first solo exhibition in Paris at the Galerie Percier, 1931. See exhibition catalogue (for which Léger wrote an introductory note): Alexander Calder, Alexandre Calder: Volumes, vecteurs, densités. Dessins, portraits (Paris: Galerie Percier, 1931). the Constructivist movement was in full bloom. Artists the world over were seduced by new mechnical forms; new sources of nontraditional materials were discovered: steel, glass, celluloid, and plastics. Even before the War, Brancusi had revealed the beauty of modulation in polished metal surfaces.

Also circa 1927, Norman Bel Geddes opened a studio in New York to redesign stoves, refrigerators, automobiles, and other serially produced objects. Aerodynamic trains belong more or less to the same period. In Germany, the Bauhaus reeducated the new generation in the severe taste of pure lines and associated style and comfort for the first time—an essentially modern accomplishment. These everyday objects of modern life, their clear and shiny, abstract and comfortable formal personality already discovered, undoubtedly constitute one of the greatest formal and aesthetic revolutions in the history of civilization.

The denaturalization of structure, and every mechanical invention in every new object, conforms to a gradual process on the march to a form of pure objectivity, in the course of which the originally Impressionist character of invention is lost. The initial form is one of naturalist inspiration, the final one is abstract.

When any new object is constructed, it borrows outlines and designs from another one. Usually that other is the one most akin or closest to it. Only after this entire process of formal gestation does the perfect integration between the final abstract structure and the fully developed functionality of the new object or invention take place. It then ceases to “resemble” this or that thing in order to resemble itself alone. This march of the natural to the formally abstract is a constant of our civilization, the mark of one of modern culture’s deepest traits. Thanks to it, the art of today has been able to influence—as possibly only the art of the Renaissance was able to before it—the industrial production of its time.

In no one more than in Calder—and in this he may have been the most faithful of the Constructivists—the dividing line between artistic creation and industrial design is less marked. His art is without inhibition in resorting to the principles of engineering and industrial design. Without the slightest ceremony, he swipes not only the materials but even the instruments and processes of mechanics in order to express himself. And he boldly avails himself of wheels, gears, levers, stems, pistons, sheets of metal, glass, and wire. No one in the realm of the visual arts has ever made use of these acquisitions with greater spontaneity, exuberance, and imagination than he. And without the slightest vestige of doctrinaire intentionalism or concern with belonging to any school. For this very reason his studio is no longer a studio but a combined blacksmith/cabinetmaker/spinner/mechanic/locksmith/ welder/devil’s workshop.

The machine is one of the modern world’s most fearful hobgoblins. Many of today’s artists still haven’t freed themselves from it. In order to rid themselves of their terror or obsession, they seek to exorcize it, like the savage before the incomprehension of the exterior world. The machine is still to these artists as nature was to prehistoric man, who perpetually yearned to fix something perennial, something permanent in geometric terms, in response to the disconcerting fluidity of the natural phenomena that struck them as terrifying, capricious, and incongruent.

Calder does not share this obsession. For him the machine is not an enchanted, magical, fascinating thing—albeit one that is mysteriously dangerous in its transformative miracles—nor is it something misunderstood. Even for him, it has lost its power as fetish. In itself it is no longer worthy of adoration. He knows it from within. He learned early on how to disassemble it. He long ago digested the mechanical subjects that are conjoined in it. And because of this he knows of what this modern deity is made. Hence his familiar treatment of her. For some time his “works of art” have had “volumes, vectors and densities.”

However, next to Calder, let us examine the attitude of another artist—a great artist called [Fernand] Léger who, in fact, belongs to the same spiritual Family as the American.

The latter finds himself dominated by the machine to such an extent that he cannot forget it. He once wrote: “Speed is the law of the day. It rolls over us and dominates us.”22“La vitesse est loi actuelle. Elle nous roule et nous domine.” Fernand Léger, “Couleur dans le monde” (1938), in Fonctions de la Peinture (Paris: Denoel, 1984), pp. 86–87. The great French painter thus confesses himself to be a slave to speed, that is to say, of mechanics. To him, the machine is beautiful but strange and inhuman.

In distributing volumes, masses, or even pieces that, together, would recompose the total unity of the machine, Léger does so only to exhibit them, simultaneously, upon a single plane. He outlines them on the canvas or paper with a fetishism that recalls that of prehistoric man carving his drives and obsessions upon stones or cave walls and transforming them into signs for exorcizing impenetrable nature. His way of revealing the secret of the machine is also symbolic. The painter of Paris sees in his figures and objects symbols of all that is powerful, impersonal, intense, and superhuman in the modern mechanical creation supreme. These figures, masses, and volumes reflect the machine’s inhuman nature.

This symbolism gives Léger’s work an element of stylization quite similar to that of Byzantine art, meaning that even when his symbols signify elements of the human body his motives indeed constitute inorganic forms intentionally distorted in the exclusive interest of rhythm. All the ancient stylizations conceal an already faint symbolic background, like worn-out currency. Behind this symbolic background hides a dominant, single, absorbing category—a god, a sacred animal, a taboo—a machine, a machine out of time and of space.

It is this that gives the whole—the drawing—a certain symmetrical rigidity. One feels in its composition the absolute empire of proportion and of harmonic relationship—characteristics of the arts of stylization of the past.

In contrast, Calder neither represents nor abstracts nor “stylizes” the machine. None of his structures is made up of purely geometric forms and volumes, analytically presented. His drawings and compositions are pure forms, converging toward an organic whole. His objects are machines, but . . . of poetry and improvisations. His stabiles and mobiles create fanciful, arbitrary, non-mechanized relationships. Occasionally monsters (or what one might call prehistoric animals), contemplative or timid vegetables, or new, ironic insects with a diabolical air issue from these geometric constructions. Yet all are alive and carry within themselves their realization and purpose.

In Calder’s hands the machine becomes volatile, gaining in virtualities that transcend functional contingencies, ceasing, for this very reason, to be a machine. Even in the motorized mobiles, the inspiration is not the machine’s reflex but its dynamic element, motion framed at the service of formal relationships and of colors, that is, of painting. Inside these panels what we see are spirals that swirl in a tortured ascension; cylinders rotating rhythmically like dancers; colors, and prisms that evolve rhythmically, unrestrained and with the grace of a bird. These pieces are mechanical extras in a scene, showing themselves off to us men.

In the non-motor-driven mobiles, then, he laughs at the machine, for he has already tamed it and left it behind. It is no longer its contained and controlled energy that is of interest to him. Rather it is the apprehension of the uncontrolled forces of the cosmos, the irreducible movement that feeds the motor of the universe, the eternal flow of forms in space.

Indeed, he seeks to capture—for it would be impossible to discipline them— within a painting that he himself set up and, in limited time, all the formal virtualities liable to be drawn in space, moved by whatever may be—by a man’s panting breath, by a gust of air, by some vibration or tremor, by chance, or even by a shove of the foot. He puts one in mind of a butterfly hunter. His objects are instruments for hunting down all the possibilities of formal beauty that the unstable balance of things can offer us in a moment.

Calder subordinates his art to a kind of automatism. However the latter is determined by a large formal plane chosen by the constructor himself. Like a boy who sets his cage upon the branch of a tree to attract a little bird, he puts his mobile in the window or in the garden outside to wait for winds that will entangle and hold them prisoner in the stems, branches, leaves, and balls of his objects that will then become animated—dancing, singing, and seized with plenitude.

Calderian automatism is controlled by experience, unlike the psychological automatism of the Surrealists. Whereas for the Surrealists the individual is a prisoner of his ego, of unconscious mechanisms, for Calder the individual feels free and rational for the first time in the face of life and the world. And—to his aesthetic whims—he toys like a god with the laws that rule the universe. The mechanism that ultimately gives rise to artistic expression is no longer unconscious or subjective but armed objectively from without.

The machine’s automatic perfection is a perennial source of enchantment for every contemporary artist. It was not only Léger who felt the weight of its fascination. In him, however, this enchantment revealed itself with particular strength. Hence the fact that his reaction to that perfection was most typical of the modern sensibility.

Léger transposes the machine’s volumes and lines statically, in search of their still perfection, devoid of virtuality. Machine and mechanical perfection are defined by the sensation of force, speed, and precision that they arouse. Isolating their forms from one another, he draws the machine’s final synthesis from them in exchange for a purely analytic presentation. In Calder, objects are the effective result of experience before this very mechanical perfection, and they assert themselves with the machine’s same synthetic autonomy.

Its ruthless placidity no longer terrifies the Calderian soul. The speed, the power, and the inhuman precision of the mechanical system do not overpower him.

Calder grew up with the machine and, for this reason, he already gazes at it from above. Today, he finds the scary, fascinating animal of the beginning of the century amusing. Holding it by the rein, he slaps the monster’s hind quarters with ironic and cordial joy, inviting all men to the same liberation.

We know well that Léger never intended to copy the machine. As he explains, he intended only to invent images of machines, just as others have invented landscapes. He uses it as others have used the nude or the still life. He seeks to express its inherent sense of strength and power. Through this path a reverse neo-academicism is forged: the machine is its model, rather than the body. Thus the world is limited to its dimension, to the effects of its perfect, adjusted strength.

However, Calder transcendentalizes and overcomes the machine. In it he seeks the only thing it cannot give—creative energy. For the machine does everything but it creates nothing. The only thing about it that interests him is the inspiration that forged it. He extracts motive power, the secret of its model behavior from the highly material, objective, fierce, and immediately utilitarian animal. The power that breathes life into it no longer represents anything supernatural to him, just as the wind or storm “machine” that frightened the savage did not either. The artist is enchanted by this only for its power of acting upon the things that surround it, its ability to trasmit and transform.

However, machine fetishism has not yet been overcome by all the artists of our time. At the end of World War I, Dada’s iconoclastic mechanism itself was unable to tame it. Desperate, [Marcel] Duchamp and [Francis] Picabia—the enfants terribles of Dadaism—wanted at least to identify themselves (similing, jesting, without solemnity or piteousness) to the victorious monster. With the usual whistling, they pretended they did not fear the dark night. In order to remain men, to preserve the human, they degraded themselves, and that is why the humor of Dada was derision above all else.

At last, it was later verified by André Breton that, unlike man, the machine could neither build nor fix itself, neither perfect nor destroy itself. Whoever possesses the power to destroy himself has the power to reconstruct and perfect himself. And thus has the power to create. Man once again felt relieved and superior to the machine. And a new humor succeeded that of Dada in modern art—a dark humor, a black humor. It was that of Calder, among others.