Hélio Oiticica left behind a body of texts, correspondence, and interviews. This essay examines them in the context of other writings from 1960s and 70s Brazil as a guide into how the artist approached and developed works such as penetrables (sculptural booths) and parangolés (both costume and ambient proposal). Going beyond the context of modern Brazil and its experimental art scene, it traces a wide genealogy for his body of work, from local traditions such as samba to European intellectual figures such as Friedrich Nietzsche.

Hélio Oiticica, firstborn son of the entomologist and photographer José Oiticica (Jr.) and grandson of José Oiticica, philologist, founder of the anarchist newspaper Ação direta (Direct action), and author of the book O anarquismo ao alcance de todos (Anarchism accessible to all), was born on July 26, 1937, in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. As a small child, Hélio was educated by private tutors and didn’t receive formal schooling until 1947, when his father was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship and the family moved to Washington, D.C. In 1954, Hélio Oiticica began studying painting under Ivan Serpa (1923–1973) at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio. In the years that followed, he had his first exhibitions, showing a series of abstract gouaches on cardboard that he called “Metaesquemas”; became linked to the Grupo Frente, who advocated abstraction and internationalism; and established friendships with the artist Lygia Clark (1920–1988) and the critic Mário Pedrosa (1900–1981), key figures in contemporary Brazilian art.

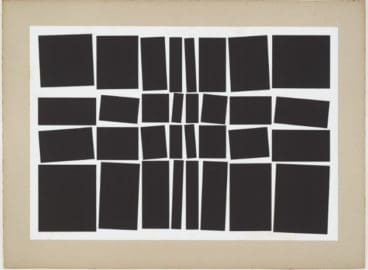

In March 1959, some of the members of Grupo Frente, together with other local artists—including Clark and Lygia Pape (1927–2004)—countersigned the Neo-Concrete manifesto written by the poet and critic Ferreira Gullar (1930–2016) and published in the newspaper Jornal do Brasil to accompany the first Neo-Concrete exhibition, held at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio. According to Gullar’s text, “The term neo-Concrete indicates a position vis-à-vis nonfigurative ‘geometric’ art (Neo-Plasticism, Constructivism, Suprematism, the Ulm-School), and, in particular, concrete art taken to a dangerous rationalist extreme.”1Ferreira Gullar: “Manifesto Neoconcreto,” in Antologia Crítica: Suplemento Dominical do Jornal do Brasil, eds. Renato Rodrigues da Silva and Bruno Melo Monteiro (Rio de Janeiro: Contra Capa, 2015), 143. In reaction to what they saw as the excessive rationalism behind contemporary abstraction, Neo-Concretists sought to expand the “expressive conquests”2Ferreira Gullar: “Manifesto Neoconcreto,” 144. of precedent movements, directing their research toward “an appraisal of verbal ‘time’ and expression as a lived fact”3Ferreira Gullar: “Museu de Arte Moderna: 1a Exposição Neoconcreta,” in ibid, 139. in order to reach an “existential experience.”4Ferreira Gullar: “Manifesto e obra,” in ibid, 150. In this context, Oiticica began his theoretical and plastic investigations into the destabilization of the pictorial plane, a pursuit that would lead him to abandon the two-dimensionality of paint on canvas in favor of experimentation in the fields of phenomenology and perception.

In “Theory of the Non-Object,” another text from 1959, Gullar raises some of the ideas that would be particularly influential in Oiticica’s work and writings. Indeed, the concept of the “non-object” perfectly fits the processes that Oiticica would develop during the 1960s. “The expression ‘non-object,’” writes Gullar, “does not intend to describe a negative object nor any other thing that may be opposite to material objects. The non-object is not an anti-object but a special object through which a synthesis of sensorial and mental experiences is intended to take place. It is a transparent body in terms of phenomenological knowledge: while being entirely perceptible it leaves no trace. It is a pure appearance.”5

In subsequent years, Oiticica produced a series of spatial pieces that, rather than function as art objects, sought to generate “states of minds” and “predispositions to creative experiences.”5Quotes in this paragraph are extracted from an interview with Marisa Alvarez de Lima, originally published in the magazine A Cigarra, on July 20, 1966, and reprinted in Hélio Oiticica, Materialismos, eds. and trans. Teresa Arijón and Bárbara Belloc (Buenos Aires: Manantial, 2013), 35. Gullar’s non-objects became, in Oiticica’s language, “ambient art”: series of works he called “Penetrables,” booths in which the viewer is invited to enter; “Bolidos,” wood-and-glass boxes that, laid on the floor, require the viewer to look down in order to appreciate them; and “Núcleos,” labyrinthine “chromatic environments” that, consisting of multiple hanging panels, the viewer can pass through. “Ambient art,” he wrote, “is the overthrow of the traditional concept of painting-frame and sculpture—that belongs to the past. It gives way to the creation of ‘ambiences’: from there arise what I call ‘anti-art.’” In these series, which he created throughout the sixties, he left behind his role as a builder of works suitable for contemplation by viewers to become instead a facilitator of experiences to be shared by participants. Indeed, he later defined the “anti-art” as “the era of the popular participation in the creative field.”

Besides the influence of the Neo-Concrete movement, Oiticia’s artistic career was marked by the intellectual tradition of his family as well as lectures on classic and modern philosophy. A figure whose name appears time after time in Oiticica’s texts and whose influence is felt throughout his work is Friedrich Nietzsche. Oiticica himself acknowledged the German philosopher’s decisive influence: “I’m son of Nietzsche and step-son of Artaud,” he retrospectively claimed in 1978.6Hélio Oiticica, in a conversation with Luis Fernando, Macalé and Jary, originally published in Folha de São Paulo, November 5, 1978, and reprinted in Materialismos, 75. He was particularly interested in Nietzsche’s conception of the Dionysiac as an artistic power linked to music, ecstasy, and community.

Not in vain, Lygia Pape, many years later, used Nietzschean terminology to describe Oiticica’s personality: “Hélio was an Apollonian young man, even a little bit pretentious. He worked with his father at the National Museum, where he learned a methodology: he was very organized and well-behaved. [. . .] In 1964, his father died and a friend of ours, Jackson [Ribeiro] took Hélio to paint the allegorical cars for Mangueira. Over there he discovered a Dionysiac space that he didn’t know [existed].”7Lygia Pape, interview by Paola Berenstein Jacques, in Estética da ginga: a arquitetura das favelas através da obra de Hélio Oiticica (Rio de Janeiro: Editora Casa da Palavra RIOARTE, 2001), 27. During one of his stays in Mangueira—the favela (shanty town) in the northern region of Rio that lends its name to the legendary escola do samba (samba school), the Mangueira samba school—he discovered a precarious construction on which was written the “magical word” parangolé—and he welcomed it as a true surrealist objet trouvé.8Irene V. Small clarifies the complex status of the term parangolé in her book Hélio Oiticica: Folding the Frame (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 188. “In fact,” she explains, “the word parangolé was not of Oiticica’s invention but rather carioca gíria, a slang term that emerged from Rio’s favelas but by 1964 had already begun to become obsolete. As Waly Salomão wrote in his posthumous homage to Oiticica, Qual é o Parangolé?, the word has no precise translation but derives from the ‘dynamic plasticity of language.’ It can refer to a disturbance, a samba rhythm, a sudden excitement, a working-class ball. But it can also suggest a linguistic style, an idle talk shaded towards the cunning, insignificant, or sly.” From that moment on, he designated his work, which was based on performance and thus far removed from traditional painting, “parangolé.” “Parangolé,” he later stated, “represents the ambient proposal that I have developed until now.”9Hélio Oiticica, interview by Alvarez de Lima, in Materialismos, 35.

Oiticica’s parangolés inherited many of the characteristics of the informal constructions in the favelas: never really finished, they are built with materials recycled from the streets. Oiticica recognized that his inspiration came from “markets, beggars’ houses, decoration of popular festivities, religious celebrations, carnival” while he emphasized the reactionary quality of “good taste” and the importance of finding creative features in ordinary, everyday life.10Hélio Oiticica, “Bases fundamentais para uma definição de ‘Parangolé” (1964), in Materialismos, 145. But conceived as garments, parangolés are intimately linked with movement and dance—as opposed to static structures—and they cannot be considered without taking into account Oiticia’s own experience as a pasista (dancer) of Mangueira. Nietzsche’s influence is once again evident here: “In song and in dance man exhibits himself as a member of a higher community,” the philosopher wrote in The Birth of the Tragedy.11Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy or Hellenism and Pessimism, trans. William August Haussmann (New York: The MacMillan Company, 1910), 46.

The parangolé is not only a costume, a construction, a shelter, but also the performer’s experience of wearing it, and that of the viewer—who now, as a “participant-work,” can interact with it, taking his or her own place within it.12Hélio Oiticica, “Anotaciones sobre el parangolé,” in Materialismos, 129. The viewer becomes this new entity who is a “participant” when he himself sees the work and a “participant-work” when he is seen from outside it by other viewers. It’s a ritual performance that erases the boundaries between artist and public, “the return to a non-intellectual state of creation, that tends to a sense of participation specifically Brazilian.”13Hélio Oiticica, interview by Alvarez de Lima, in Materialismos, 35. It promotes the entry of the masses into the field of artistic creation, because, as the German philosopher states, in the wake of Dyonisian emotions, “the subjective vanishes to complete self-forgetfulness.”14Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy or Hellenism and Pessimism, 51. Parangolé is the “anti-art” par excellence.

In a true Nietzschean manner, Parangolé does not seek to establish a new moral, but rather to “demolish all the morals”: during the 1960s, Oiticica embraced marginality. “Suddenly,” he wrote to Lygia Clark in 1969, “here [in Mangueira], everything that was ‘sin’ became virtue.”15Hélio Oiticica to Lygia Clark, June 7, 1969, in Lygia Clark Hélio Oiticica. Cartas 1964–74, ed. Luciano Figueiredo (Rio de Janeiro: Editora UFRJ, 1998), 103. His fascination with the streets as “a nourishment opposed to everything abstract,” his relationship with the toughest personalities of the favela, and his theorization of violence as a legitimate tool for liberation—all these elements are important parts of his radical conception of artistic, social, and political life.16Hélio Oiticica, in a conversation with Luis Fernando, Macalé and Jary, op. Cit., 76. His conceptual project pairs the old revolutionary—the anarchist figure of his grandfather José—with the contemporary outlaw. And the directive “Be an outlaw, be a hero” was one of his banners.17“Be an outlaw, be a hero” [Seja heroi, seja marginal], is not only is a slogan but also an actual work (a flag ) that Oiticica made in 1968.

All of Oiticica’s ideas shape a theoretical framework within which to act upon European cultural modernity in collision with local Brazilian traditions. It’s a complex pop-culture universe where the philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty, the musician Caetano Veloso, the philosopher Immanuel Kant, and the infamous Cara de Cavalo (Horseface), a criminal murdered by vigilantes, coexist. In effect, in his texts, which are inseparable from his artwork, Oiticica intended “to explain the appearance of an avant-garde and justify it, not as a symptom of alienation, but as a decisive factor in its collective progress.”18Hélio Oiticica, “Esquema Geral da Nova Objetividade,” in Nova Objetividade Brasileira, exh. cat. (Rio de Janeiro: MAM-RJ, 1967, and reprinted in Irene V. Small, Hélio Oiticica: Folding the Frame (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 98. Thus Mondrian and carnaval live together within them.

“What matters: the creation of a new language,” he wrote in 1973. “Destiny of Brazilian modernity asks for the creation of that language: relations, swallowing, all the phenomenology of that process [. . .] asks for and demands (under penalty of consuming itself in a conservative academicism) that language.”19Hélio Oiticica, “Brasil Diarrea,” originally published in Arte brasileira hoje, ed. Ferreira Gullar (Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1973), and reprinted in Materialismos, 111. His proposals, in this sense, are deeply rooted in the anthropophagic project first formulated in the poet Oswald de Andrade’s (1890–1954) “Manifesto Antropófago” (“Cannibalist Manifesto”) of 1928. In an attempt to adapt the indigenous ritual attitude toward the foreign to the avant-garde, it encourages artists to appropriate and “digest” European theories and styles. The poetic and tangled text, let’s remember, was dated in a very particular way: “In Piratininga. Year 374 of the Swallowing of Bishop Sardinha,” the Portuguese religious figure who was, according to historical record, eaten by members of the Tupi tribe. In consonance with that statement of principles, de Andrade writes: “Tupi or not tupi, that is the question.” The “Manifesto Antropófago” foresees and, in a way resolves, an important part of Occidental culture’s debate in the second half of the twentieth century in that de Andrade addresses many of the problems that post-colonial and deconstructive discourses on globalization, hybridization, Otherness, Eurocentrism, etc., have tried to address. And he does so by transforming, in a cultural form, the encounter between the existential aspects of Shakespeare’s literature and the Tupi cannibalistic ritual. Hélio Oiticica is, likewise, a son of this tradition.

- 1Ferreira Gullar: “Manifesto Neoconcreto,” in Antologia Crítica: Suplemento Dominical do Jornal do Brasil, eds. Renato Rodrigues da Silva and Bruno Melo Monteiro (Rio de Janeiro: Contra Capa, 2015), 143.

- 2Ferreira Gullar: “Manifesto Neoconcreto,” 144.

- 3Ferreira Gullar: “Museu de Arte Moderna: 1a Exposição Neoconcreta,” in ibid, 139.

- 4Ferreira Gullar: “Manifesto e obra,” in ibid, 150.

- 5Quotes in this paragraph are extracted from an interview with Marisa Alvarez de Lima, originally published in the magazine A Cigarra, on July 20, 1966, and reprinted in Hélio Oiticica, Materialismos, eds. and trans. Teresa Arijón and Bárbara Belloc (Buenos Aires: Manantial, 2013), 35.

- 6Hélio Oiticica, in a conversation with Luis Fernando, Macalé and Jary, originally published in Folha de São Paulo, November 5, 1978, and reprinted in Materialismos, 75.

- 7Lygia Pape, interview by Paola Berenstein Jacques, in Estética da ginga: a arquitetura das favelas através da obra de Hélio Oiticica (Rio de Janeiro: Editora Casa da Palavra RIOARTE, 2001), 27.

- 8Irene V. Small clarifies the complex status of the term parangolé in her book Hélio Oiticica: Folding the Frame (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 188. “In fact,” she explains, “the word parangolé was not of Oiticica’s invention but rather carioca gíria, a slang term that emerged from Rio’s favelas but by 1964 had already begun to become obsolete. As Waly Salomão wrote in his posthumous homage to Oiticica, Qual é o Parangolé?, the word has no precise translation but derives from the ‘dynamic plasticity of language.’ It can refer to a disturbance, a samba rhythm, a sudden excitement, a working-class ball. But it can also suggest a linguistic style, an idle talk shaded towards the cunning, insignificant, or sly.”

- 9Hélio Oiticica, interview by Alvarez de Lima, in Materialismos, 35.

- 10Hélio Oiticica, “Bases fundamentais para uma definição de ‘Parangolé” (1964), in Materialismos, 145.

- 11Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy or Hellenism and Pessimism, trans. William August Haussmann (New York: The MacMillan Company, 1910), 46.

- 12Hélio Oiticica, “Anotaciones sobre el parangolé,” in Materialismos, 129. The viewer becomes this new entity who is a “participant” when he himself sees the work and a “participant-work” when he is seen from outside it by other viewers.

- 13Hélio Oiticica, interview by Alvarez de Lima, in Materialismos, 35.

- 14Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy or Hellenism and Pessimism, 51.

- 15Hélio Oiticica to Lygia Clark, June 7, 1969, in Lygia Clark Hélio Oiticica. Cartas 1964–74, ed. Luciano Figueiredo (Rio de Janeiro: Editora UFRJ, 1998), 103.

- 16Hélio Oiticica, in a conversation with Luis Fernando, Macalé and Jary, op. Cit., 76

- 17“Be an outlaw, be a hero” [Seja heroi, seja marginal], is not only is a slogan but also an actual work (a flag ) that Oiticica made in 1968.

- 18Hélio Oiticica, “Esquema Geral da Nova Objetividade,” in Nova Objetividade Brasileira, exh. cat. (Rio de Janeiro: MAM-RJ, 1967, and reprinted in Irene V. Small, Hélio Oiticica: Folding the Frame (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 98.

- 19Hélio Oiticica, “Brasil Diarrea,” originally published in Arte brasileira hoje, ed. Ferreira Gullar (Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1973), and reprinted in Materialismos, 111.