The Museum of Modern Art has just received what is arguably one of the most transformative donations in its history: more than one hundred modern works produced by thirty-seven Latin American masters, which have entered the collection through the generosity of the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros.

This theme was developed to share information about works and artists that are part of the Cisneros gift. The original content items in this theme are listed below.

To read more about the Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Research Institute for the Study of Art from Latin America click here.

The gift that The Museum of Modern Art is receiving from the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros (CPPC) will transform MoMA’s collection of modern and late modern art for a variety of reasons. First, it is impressive in both size and scope, including 102 works of art (comprised of sixty-eight paintings, eleven sculptures, twenty drawings, and three prints) by thirty-seven artists born in and/or working in Latin America during the twentieth century and representing four countries, three constellations articulated around three foci of artistic creation, and a production that spans more than fifty years.

Second, it is a gift that reflects more than forty years of serious collecting. Begun in the 1970s, the CPPC’s initial emphasis was Venezuela, and its holdings include a retrospective core of works by important Venezuelan artists such as Gego, Carlos Cruz-Diez, Jesús Rafael Soto, and Alejandro Otero.

Later, in the 1990s, in consultation with respected scholars and curators, the CPPC engaged in a more ambitious endeavor: expanding its focus to other parts of the continent. The aim was to bring together a group of artworks that would, in turn, represent the three most productive constellations of Constructivist-based (for lack of a better term) art in the region. And this goal was attained brilliantly. This is perhaps one of the most notable particularities of the CPPC: far more than a collection of isolated masterpieces, it evokes the complex, multilayered, and often contradictory dialogues between twentieth-century Latin American artists and their creative processes, as well as between the different regions in which they worked, their contextual specificities, and their projected values.

Thinking of these art historical moments in terms of constellations allows for a better understanding of what happened in Buenos Aires and Montevideo, in work from Joaquín Torres García to Madí, the Arturo group, or Arte Concreto-Invención; in Brazil, both in Sao Paulo and Río de Janeiro, in the context of the Concrete and Neo-Concrete movements; and in Venezuela, from the early experiments in Concrete and Kinetic art. This is what makes the Cisneros’ collection one of a kind—its continental breadth attests to the various explorations that the Constructive, Concrete, Neo-Concrete, and nonobjective artists from Latin America undertook, and it is one of the few collections that can, simultaneously, suggest the relationship between their work and the contemporary artistic production occurring elsewhere.

The Cisneros gift will broaden public exposure to Latin American art, and it represents an enormous challenge and an exciting historical opportunity for The Museum of Modern Art. The Museum has the responsibility of integrating these works into its collection, not by assimilating them into a general (and generalizing) narrative of modern art but rather by accounting for and making visible the singularity of the artistic practices that they represent—or, their incommensurability vis-à-vis their canonic historical references, as Luis Pérez-Oramas, the Estrellita Brodsky Curator of Latin American Art at MoMA, has often stated.

These Latin American works expand an already important collection of pieces from the region (many of which were also donated by the Cisneros). They offer an unprecedented opportunity for the Museum to continue its efforts to acknowledge and present a more complex narrative on modern art—which, ongoing since the museum’s inception, have grown stronger with initiatives such as C-MAP. As this donation makes clear, a serious engagement with Modernism in Latin America shows the insufficiencies of any hegemonic art historical narrative: these new works are valuable not because they are oddities, but rather because in presenting a different history, they remind us of the contingency of all histories, narratives, and sense-making operations.

The Museum, we know it, is a sense-making machine—as are the artworks that live within it and the curatorial narratives that are presented alongside and with them. If, as detailed in its mission statement, “The Museum of Modern Art is dedicated to being the foremost museum of modern art in the world” and if one of the ways of achieving this is to “periodically reevaluate itself,” encouraging “openness and willingness to evolve and change,” then the Cisneros gift is an opportunity like no other.

Maybe this major gift will push some of the voices in the sense-making machine of the Museum toward a more plural, even if less-harmonious, choir.

- The 102 works that compose the gift were produced between 1940 and 1990. The following artists are represented (the number of works by each appears in parentheses after their names): Hércules Barsotti (13), Omar Carreño (2), Aluísio Carvão (1), Lygia Clark (5), Waldemar Cordeiro (1), Carlos Cruz-Diez (3), Geraldo de Barros (1), Amílcar de Castro (1), Willys de Castro (5), Hermelindo Fiaminghi (1), María Freire (1), Gego (Gertrude Goldschmidt; 9), Carlos González Bogen (2), Elsa Gramcko (1), Alfredo Hlito (2), Judith Lauand (1), Gerd Leufert (4), Raúl Lozza (2), Tomás Maldonado (1), Mateo Manaure (1), Francisco Matto (1), Juan Melé (1), Juan Molenberg (1), Rubén Núñez (2), Hélio Oiticica (5), Alejandro Otero (13), Lygia Pape (2), Rhod Rothfuss (1), Luiz Sacilotto [1], Mira Schendel [5], Ivan Serpa [1], Antonieta Sosa [1], Jesús Soto [6], Rubem Valentim [2], Gregorio Vardánega [1], Virgilio Villalba [1], and Franz Weissmann [1].

Rio de la Plata

Born in the Veneto region of Italy, Vardanega moved to Argentina with his family at a young age, settling in Buenos Aires. In 1946, he became a member of the Asociación Arte Concreto-Invención, and in 1955 was a founding member of Grupo Arte Nuevo. Vardanega moved to Paris in 1959 with his wife, the kinetic artist Marta Boto. His early works focused on illusions of motion created by spatial reliefs and transparencies. In his later kinetic production, he incorporated electronics, lights, and reflections.

Born in Montevideo, Uruguay, Rothfuss studied painting at the Círculo de Bellas Artes and later at the National Academy, where he met Carmelo Arden Quin at an exhibition of works by Emilio Pettoruti. Shortly thereafter, Rothfuss moved to Buenos Aires and became acquainted with artists Gyula Kosice and Tomás Maldonado. In 1944, they were part of the editorial board of the seminal magazine Arturo, which published Rothfuss’s renowned article “The Frame: A Problem in Contemporary Art,” an enduring reference for future discussions of Concrete art in the Argentine avant-garde. Together with Arden Quin, Kosice, and others, Rothfuss founded the Madí art group in 1946 and disseminated the Madí manifesto at the group’s inaugural exhibition. In the 1950s, Rothfuss was intrigued by perceptual displacements produced by adjacent polygons and addressed the subject in his article “An Aspect of Superimposition,” the ideas of which are embodied in Yellow Oblong. The work presents visually distinct blocks of color joined at the corners and features the artist’s signature irregular frame. Rothfuss died at 49, leaving behind a small body of work, which makes this gift a rare and extraordinary opportunity to welcome an example of the artist’s production into the collection.

One of the most important Uruguayan artists of the twentieth century, Francisco Matto attended Joaquín Torres-García’s atelier from 1943 until the master’s death in 1949. Though aesthetically indebted to Torres-García, Matto went on to create his own unique oeuvre, which bridged a prehistoric realm of symbolic forms with the language of contemporary art. A collector of Pre- Columbian art, Matto introduced the pictograms and totems of ancient objects into his own repertory of forms. The present sculpture, Couple, pairs two elemental forms as if to accentuate their formal and material differences: one is biomorphic, the other rectilinear; one is made of marble, the other of wood. Dating from 1982, the sculpture would add immeasurably to the two wood sculptures by Matto from the 1960s already in the collection.

Villalba was born in Tenerife, in the Canary Islands, and in 1929 settled with his family in Argentina, where he studied at the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes. He joined Asociación de Arte Concreto-Invención in 1946 and was later involved with Grupo Arte Nuevo, established in 1955 by Carmelo Arden Quin and Aldo Pellegrini. Villalba spent a year in Oxford, England, on a scholarship from the British Council and then settled in Paris in the early 1960s, where he progressively abandoned geometric abstraction in favor of figurative art.

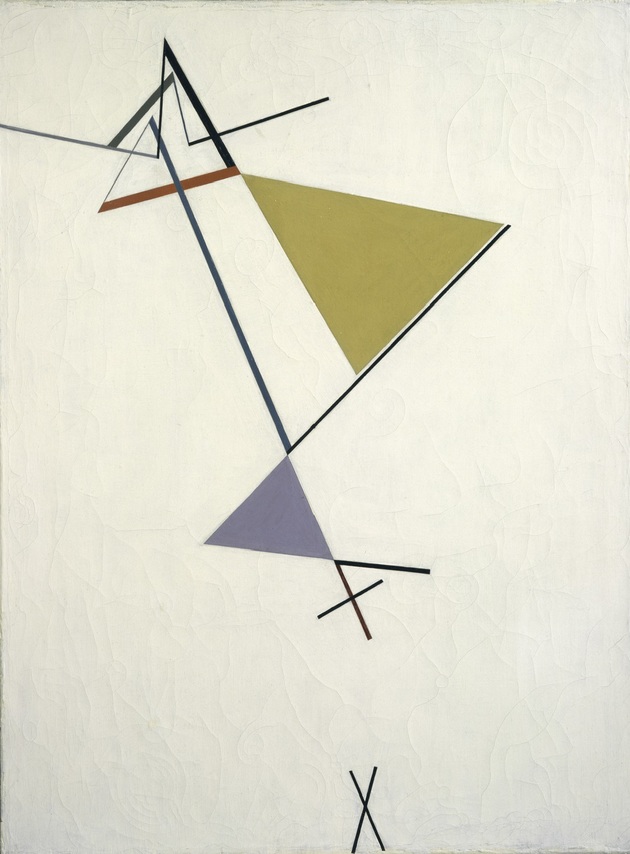

Tomás Maldonado played a decisive role in the emergence of abstraction in Argentina and was one of its most spirited exponents. As a freshman at the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes Manuel Belgrano, he co-authored the “Manifesto of Four Young Men” with Alfredo Hlito, Claudio Girola, and Jorge Brito and distributed their denunciation of the academy’s corruption and self-rewarding behavior at the National Salon. In 1944, his woodcut design illustrated the front and back covers of the seminal Arturo: Revista de Artes Abstractas. Following the group’s dissolution, Maldonado cofounded the Asociación de Arte Concreto-Invención and disseminated the Inventionist manifesto at the group’s inaugural exhibition in 1946, announcing that “the era of representational fiction has come to an end.” In the late 1940s, Maldonado traveled to Europe, where he met Georges Vantongerloo and Max Bill. A renowned figure in the academic realms of design, ecology and technology, Maldonado was director of the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm, Germany, from 1955 to 1968, when he settled permanently in Milan.

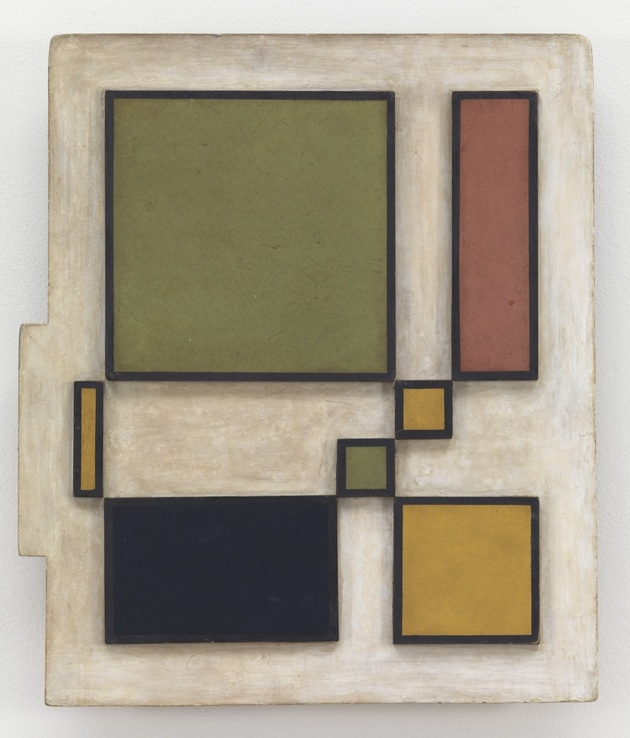

Raúl Lozza was a founding member of the Asociación Arte Concreto-Invención (AAC-I) in 1945. During its brief existence, the group developed the concept of the irregular frame first promoted by Rhod Rothfuss, and its members produced works whose compositions gradually split into separate forms joined together with metal rods. Relief no. 30 is an example of this type of “coplanar” work, the AAC-I’s most distinguished formal breakthrough. After ending his affiliation with the organization, Lozza founded his own movement, Perceptismo in 1948. A manifesto was published the following year, and the magazine Perceptismo appeared between 1950 and 1953. Invention no.150 is an example of the solution provided by Lozza’s Perceptist doctrine for a concrete structure driven to its ultimate self-referential conclusion.

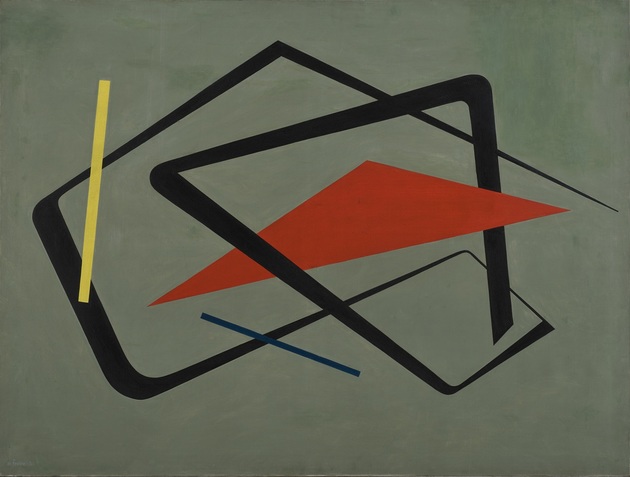

Co-author with Tomas Maldonado, Claudio Girola and Jorge Brito of the 1942 “Manifesto of Four Young Men,” Alfredo Hlito was also a founder of the Asociación de Arte Concreto-Invención, a central Concrete art movement in Argentina. As a member of the group, Hlito was a signatory of the Inventionist manifesto while simultaneously acknowledging the influence of Joaquín Torres-García’s Constructivist style as a driving force in his work.

Juan Melé joined the Asociación de Arte Concreto-Invención in 1946 following the group’s inaugural exhibition. In 1948, he traveled to Paris on a scholarship from the French government to study at the École du Louvre and took private lessons with Sonia Delaunay and Georges Vantongerloo. He became acquainted with Michel Seuphor, Antoine Pevsner, Max Bill, and other artists and intellectuals working in the languages of Concrete art and abstraction. Irregular Frame no. 2 dates from Melé’s initial contact with the Concrete art group and is a compelling exploration of the compositional possibilities opened up by the irregular frame, a principal concern of the Argentine avant-garde, as proclaimed by Rhod Rothfuss in his 1944 article in Arturo magazine.

María Freire, one of Uruguay’s most prolific Concrete artists, cofounded the group Arte No Figurativo in 1952 with her husband José Pedro Costigliolo and fellow artist Antonio Llorens. The group was at the forefront of Uruguayan art, rejecting figurative work in favor of pure abstraction. In 1953 Freire was invited to participate in the second São Paulo Bienal, where she encountered paintings by Europeans such as Piet Mondrian and Friedrich Vordemberge-Gildewart. That experience, paired with her close association with artists in the Argentine Madí movement, greatly influenced the geometric vocabulary of Freire’s work.

Brazil

Austrian by birth and Brazilian by choice, Franz Weissmann was born in Knittefeld in 1911 and moved to Brazil when he was 10 years old. He studied art and architecture and, in 1948, moved to Belo Horizonte to teach design and sculpture in that city’s first Escola de Arte Moderna. In 1960 he moved to Europe, residing in Paris and Irún (Spain) until he returned to Brazil in 1965. Initially a figurative artist, he shifted to abstraction in the late 1940s and early 1950s. His sculptures explore relationships of volume and space, often through the use of voids and modular elements. Like many of his contemporaries, he was a signatory of the Neo- Concrete Manifesto and a member of Grupo Frente.

A lifelong resident of Rio de Janeiro, Iván Serpa was not only a gifted painter but also, and primarily, an influential teacher and mentor. In 1951 he was appointed as the principal instructor at the school of the Museu de Arte Moderna in Rio. His classes were so popular that he later founded an open studio where students were invited to create and critique. He taught some of the most prominent Brazilian artists of the twentieth century—Hélio Oiticica, Lygia Clark, Lygia Pape, Aluísio Carvão—and with them created Grupo Frente. Serpa studied painting, drawing, and engraving informally with Axl Leskoschek, but his most influential intellectual and creative relationship was perhaps the one he established with the critic Mario Pedrosa.

Luiz SACILOTTO (Brazilian, 1924–2003). Concreção 58 (Concretion 58). 1958. Enamel on metal and acrylic over plywood. 7 7/8 × 23 5/8 × 12 in. (20 × 60 × 30.5 cm). Number of works in collection: 0.

Pape was an intrepid explorer of mediums, experimenting with painting, printmaking, film, installation, graphic design, jewelry design, sculpture, choreography, and performance. Along with Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticica, she was a member of Grupo Frente, the Rio de Janeiro-based group of Concretists. In 1959, abandoning what she and other colleagues felt to be the rigidity of Frente’s formal principles, she helped to establish Neo-Concretism, which, while adhering to abstraction, emphasized the expressive and personal qualities of artwork as well as the importance of the presence and participation of viewers. Pape’s central contribution lies in her sustained enquiry into how abstract geometric compositions can generate experiential, multi-sensory encounters for viewers. As she explained, she sought to understand “the sensorial as a form of knowledge and consciousness.”

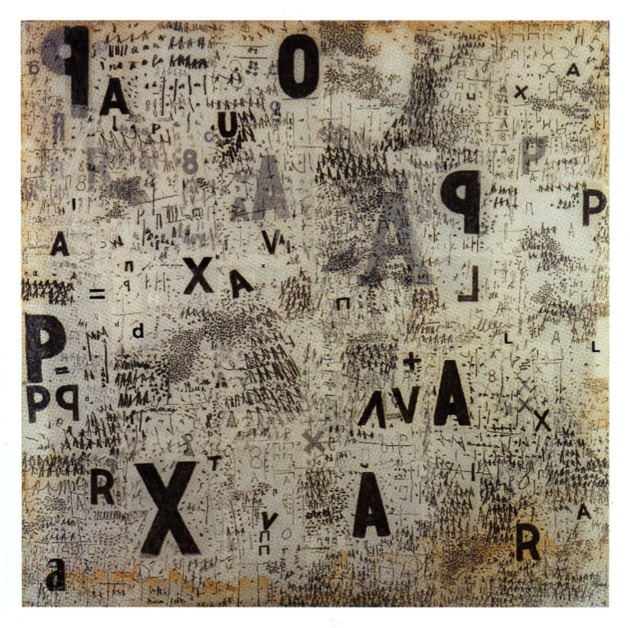

One of the major figures of postwar Brazilian art, Mira Schendel worked across mediums, from painting and sculpture to artists’ books. Her wide-ranging practice encompasses her voluminous production of minimal monotypes; radical, three-dimensional works such as Droguinhas and Trenzinho; and experiments with poetry and non-linear, text-based forms. She redefined drawing for generations of contemporary Brazilian artists.

Hélio Oiticica trained at the Museu de Arte Moderna in Rio de Janeiro under the guidance of Iván Serpa and began his career as an exponent of Concrete art, joining Grupo Frente, and the Neo-Concrete movement.. In his earlier works, Oiticica experimented with color and used it to activate the flat surface of painting—exploring movement and rhythm as means of challenging bi-dimensionality. Of critical importance are Oiticica’s Parangolés, wearable structures activated by human contact. Made of diverse materials, they were intended to be used while their wearers were dancing samba. Arguably, the Parangolés encapsulate the artist’s primary concerns and explorations of color, space, movement, structure, and the integration of art and life. They are objects that radically bridge the gap between the artwork and its user.

Initially trained as an elementary school teacher, Judith Lauand became an influential painter and printmaker in São Paulo, where she studied engraving with Lívio Abramo. In 1955, at the invitation of Waldemar Cordeiro, Lauand joined Grupo Ruptura, the only woman to do so. In 1963, she cofounded with Hermelindo Fiaminghi and Luiz Sacilotto the influential exhibition space Galeria Novas Tendencias in São Paulo. A meticulous artist, Lauand’s works are often the product of rigorous mathematical observations and calculations and, as a result, they convey the illusion of movement through the tension of the forms.

Born in Salvador de Bahía in 1922, Valentim graduated from dentistry school in 1946 and shortly thereafter decided to devote himself to painting. He learned basic painting techniques from popular mural painter Arthur Come-Só but was essentially a self-taught artist whose visual language was strongly influenced by the Afro-Brazilian cult of candomblé. Valentim went on to study journalism at the Universidade de Bahia, graduating in 1953, and moved to Rio de Janeiro in 1957, where he became an assistant professor at the Instituto de Belas Artes. Valentim’s signature contribution to Brazilian geometric abstraction is the particular form of symbolism and mystical figuration that he introduced within the practice of Constructivist art.

Born in São Paulo in 1920, Hermelindo Fiaminghi studied at the Liceu de Artes e Ofícios under Waldemar da Costa and later trained with Alfredo Volpi. A painter, graphic designer, professor, critic, and publicist, Fiaminghi is known for the visual rhythm of his compositions and for his frequent use of a reduced palette. He was a member of Grupo Ruptura and participated in the Concrete poetry movement by helping poets with the graphic design of their texts. Among his notable achievements are his pioneering work with offset and his coining of the term Corluz (colorlight) to refer to his experiments with light and color.

Born in Uberlandia, in the state of Minas Gerais, de Castro moved to São Paulo in 1941. A prolific creator, he worked in theater, graphic and industrial design, music, poetry, chemistry, and visual arts. Like most artists of his generation, he participated in both the Concrete and Neo-Concrete movements. He saw his artistic work as inseparable from his other pursuits and used the visual vocabulary of Concrete art to explore the interplay of space, planes, and color, creating virtual spaces regulated by perception and geometric progression.

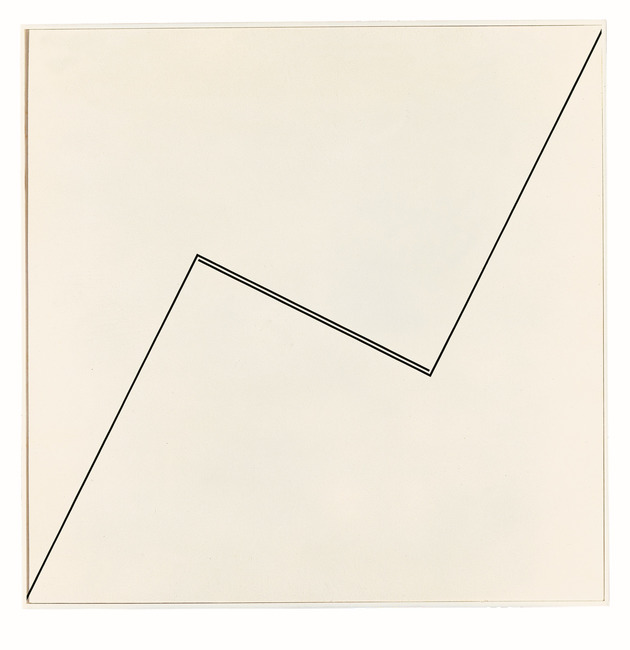

Amilcar de Castro, a leading figure of the Neo-Concrete movement, was one of the foremost Brazilian sculptors of the twentieth century. His earliest innovations, achieved in the early 1950s, preceded those of other Neo-Concrete artists by almost a decade and can be seen as important precursors to Minimalism. Based on the ideas of the cut and the fold, De Castro’s sculptures began as sketches that he would model in paper and then translate into small metal mockups, ultimately increasing the scale for finished compositions. With its triangular wedge cut out and then reinserted off-kilter into the circular steel plate, Untitled, made in 1960—the year after De Castro signed the Neo-Concrete Manifesto—would introduce the artist into MoMA’s collection with an iconic piece.

Originally trained as a painter, Geraldo de Barros began experimenting with photography in 1946. After several smaller displays of his early expressionist-style paintings, he held a solo exhibition of abstract photographs at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo in 1950. Soon thereafter, he traveled to Paris on a scholarship from the French government and studied engraving at the École Supérieur des Beaux-Arts, crossing paths with a number of figures who would influence his artistic development: Giorgio Morandi, Brassaï, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Maria Vieira da Silva, François Morellet, Otl Aicher, and Max Bill. Upon his return to São Paulo in 1952 de Barros became one of the founding members of Grupo Ruptura and in 1954 he began designing furniture as part of the Unilabor collective. This work would diversify MoMA’s holdings of de Barros’s work and broaden the representation of his cross-disciplinary achievements.

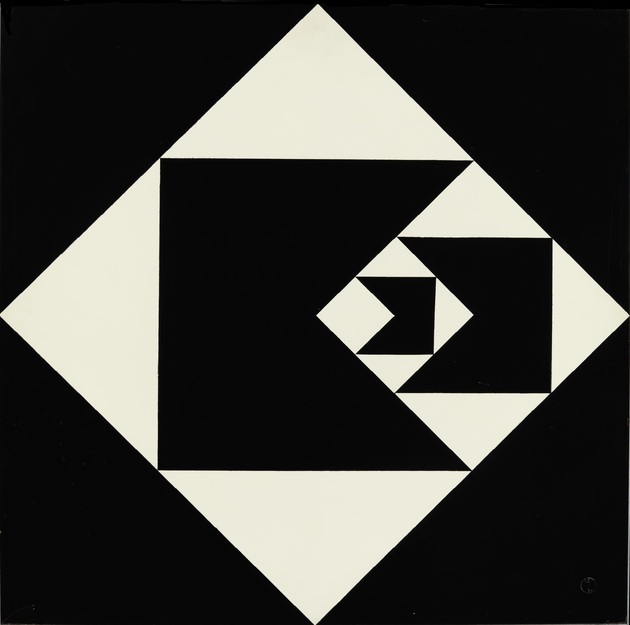

Waldemar Cordeiro was a critical and outspoken figure within the Brazilian Concrete art movement. With Geraldo de Barros, Lothar Charoux and Luiz Sacilotto, he founded Grupo Ruptura in 1952 and became the voice of the organization. His support of the group’s adherence to mathematical principles is apparent in Idéia visível (Visible Idea), one of a series of works that draws from the classical proportions of the golden rectangle and the logarithmic spiral. Painted in 1956, the same year Cordeiro organized the first Exposição nacional de arte concreta (National Exhibition of Concrete Art) at the Museu de Arte Moderna in São Paulo, it would be the earliest work by Cordeiro in the Museum’s collection, which includes two strong examples of his later, computer-based prints.

Initially trained in Brazil under the landscape architect Roberto Burle-Marx, Clark moved to Paris in 1950 to study with Fernand Léger. She returned to Brazil two years later, joining Grupo Frente in 1954 and signing the Neo- Concrete Manifesto in 1959. Her practice occupies a singular space where painting, sculpture, performance, and art therapy converge, linking the physical and metaphorical, mind and matter.

Aluísio Carvão was a painter, illustrator and stage designer. In 1952, he attended Iván Serpa’s painting classes at the Museu de Arte Moderna in Rio de Janeiro and the following year joined Serpa’s newly formed Grupo Frente, whose members included fellow Concrete artists Hélio Oiticica, Lygia Clark, and Lygia Pape. Carvão participated in the First National Exhibition of Concrete Art in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro in 1956–57 and, along with his contemporaries in Grupo Frente, signed the Neo-Concrete Manifesto in 1959. A year later he attended the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm, Germany, as a visiting artist. He returned to Rio in 1963 to become a professor at the school of the Museu de Arte Moderna.

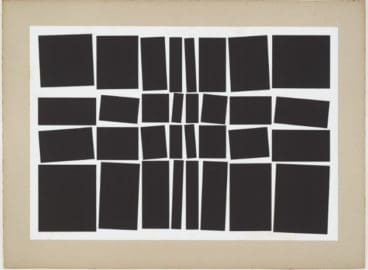

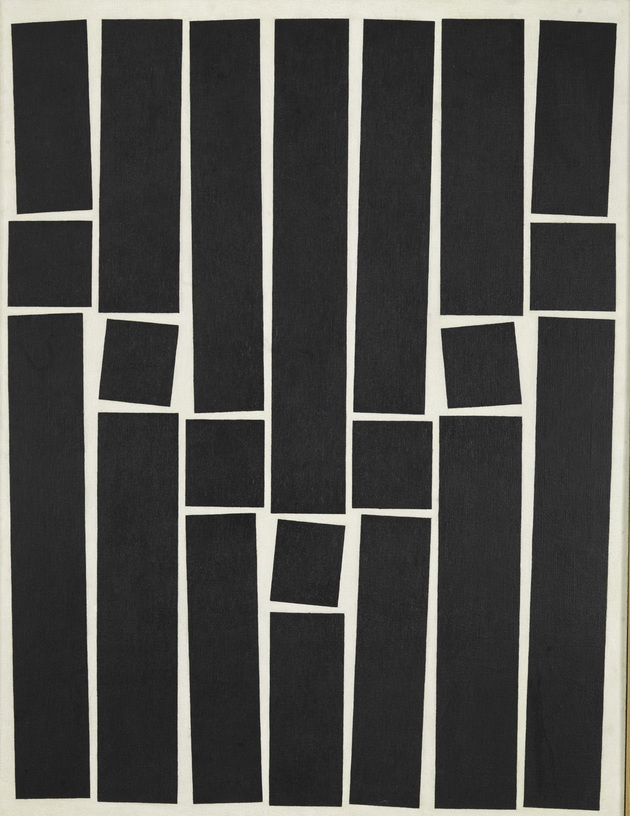

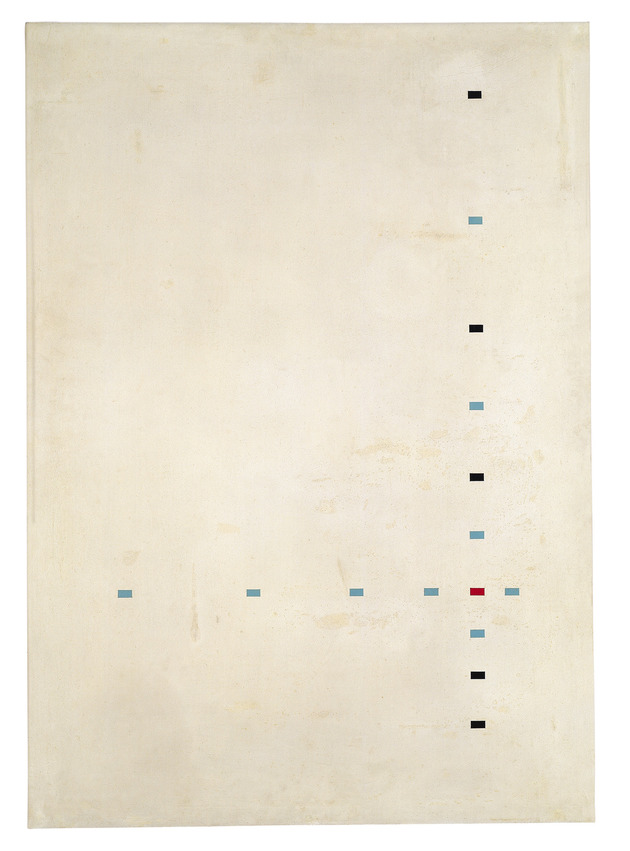

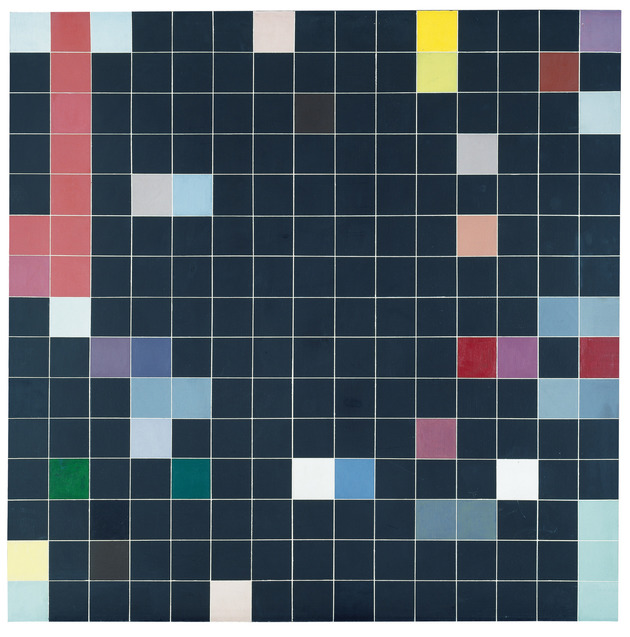

Before dedicating himself to art, Barsotti studied chemistry and worked as an industrial and print designer. He was a founder of and pivotal figure in the Brazilian school of geometric abstraction and worked closely with Willys de Castro, with whom he established the Estudio de proyectos gráficos (Workshop for Graphic Projects), where he made his first Concrete works. Barsotti refused to sign the Neo- Concrete Manifesto but joined the movement and participated in the group’s exhibitions. He was greatly interested in optical intensity and ambiguity, and he often used a limited black and white palette to challenge the flatness of the surface. Using graphic design language, few chromatic elements, and abundant “empty” space, Barsotti achieved maximum visual results.

Venezuela

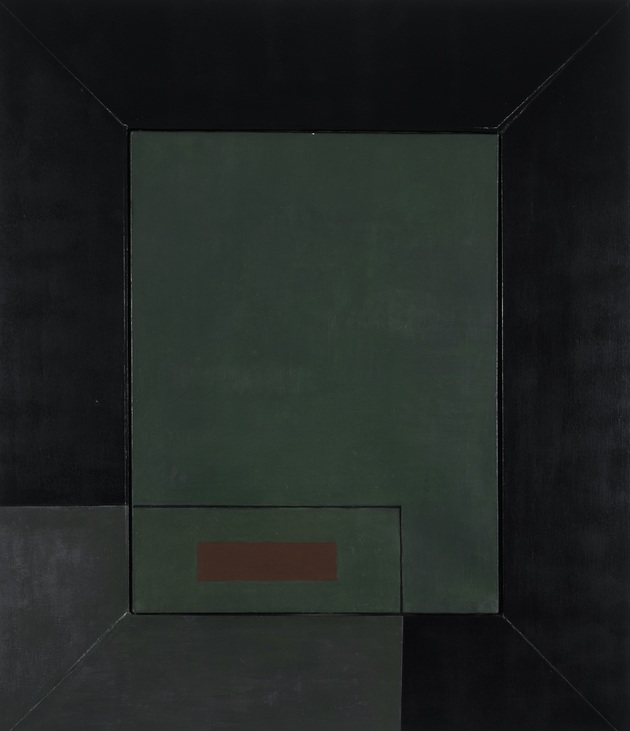

Gerd Leufert was born in Germany and had a successful career as a graphic designer there prior to his emigration to Venezuela in 1951. He met his wife, the artist Gego (Gertrud Goldschmidt), in 1953, and their work from that time forward reflects their rich artistic dialogue. The paintings cited above would be the first by Leufert to enter the museum’s collection. Their range of stylistic themes and media are a fitting representation of his broad practice and experimentation, currently represented in the collection by drawings and prints. he was part of the avant-garde group of Venezuelan “Dissidents,” and one of its most articulate voices. An active member of the Communist Party, Bogen adopted Social Realist figuration in the early 1960s and adhered to that style until the end of his life. He is widely considered one of the finest Venezuelan artists of the twentieth century. with Tomás Maldonado, Claudio Girola and Jorge Brito the 1942 “Manifesto of Four Young Men,” Alfredo Hlito was also a founder of the Asociación de Arte Concreto-Invención, a central Concrete art movement in Argentina. As a member of the group, Hlito was a signatory of the Inventionist manifesto while simultaneously acknowledging the influence of Joaquín Torres-García’s Constructivist style as a driving force in his work.

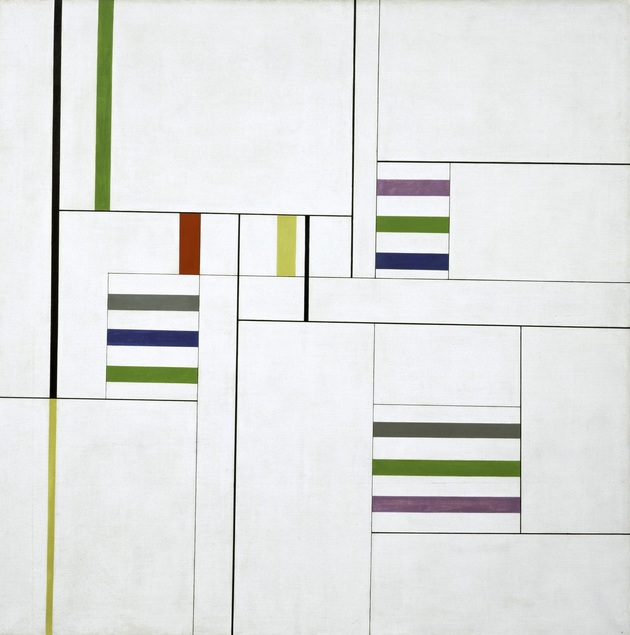

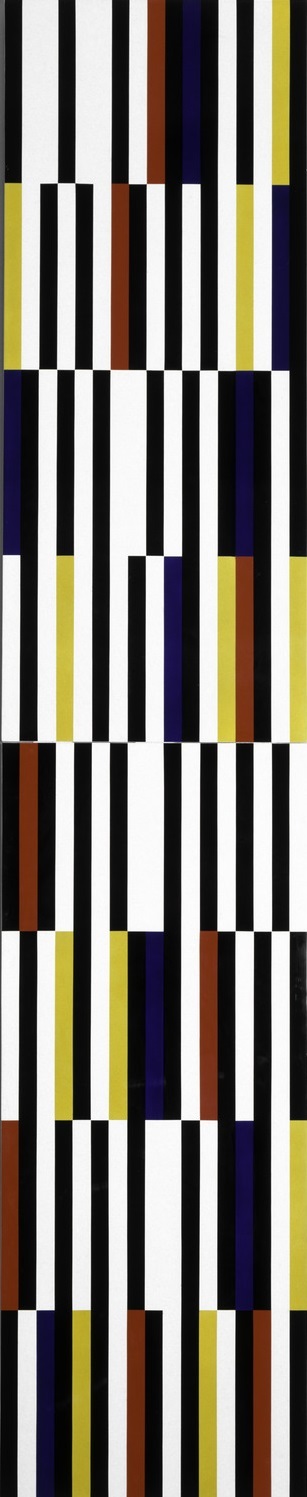

One of the major references of late modern art in Latin America, Otero’s early series of monochromatic canvases titled Colored Lines on White Background (1948-51) are the first examples of radical abstraction produced in the Americas. In 1952, Otero produced a series of monumental murals for the University City of Caracas, an ambitious project by architect Raul Carlos Villanueva, and in 1956, the seminal piece of his well-known series of Colorhythms was acquired by Alfred H. Barr Jr. for the Museum’s collection. During the 1970s, Otero focused on the production of Spatial Structures, large-scale kinetic sculptures installed in public locations in Venezuela, Italy, and the United States. A gifted writer, Otero led one of the most brilliant and daring investigations of early non-objective abstraction in the Americas.

Elsa Gramcko was a leading figure among Venezuela’s female abstractionists. She began her career under the tutelage of her friend Alejandro Otero. Unlike most Constructivist works, which channel an industrial neutrality, Gramcko’s production features a sensuous approach to materiality. Her abstract paintings, always on canvas, assert an organic dimension as well as a sense of intimacy and are among Venezuela’s finest geometric abstractions. Beginning in the 1960s, Gramcko became the preeminent Informalist artist in her country, working with discarded materials and archeological finds. Ill health brought her artistic practice to a halt in 1979, but she remained a central reference in the Venezuelan art scene.

Antonieta Sosa is a leading Conceptual artist in Venezuela and a seminal figure in the history of performance art and Happenings in Latin America. As with most of the artists who came of age in Venezuela during the 1960s, her formal and intellectual training are closely tied to geometric abstraction, although her artistic practice later shifted radically toward experimentation and participatory art. Sosa assumed a leading role in the contemporary art scene through her performative deconstruction of abstraction during the 1960s. Since the 1970s her work has been devoted to performance, Happenings and installations, many of them based on her personal measurement system derived from the dimensions of her own body. Sosa is regarded as one of Venezuela’s most influential art teachers and has had a pronounced impact on younger generations.

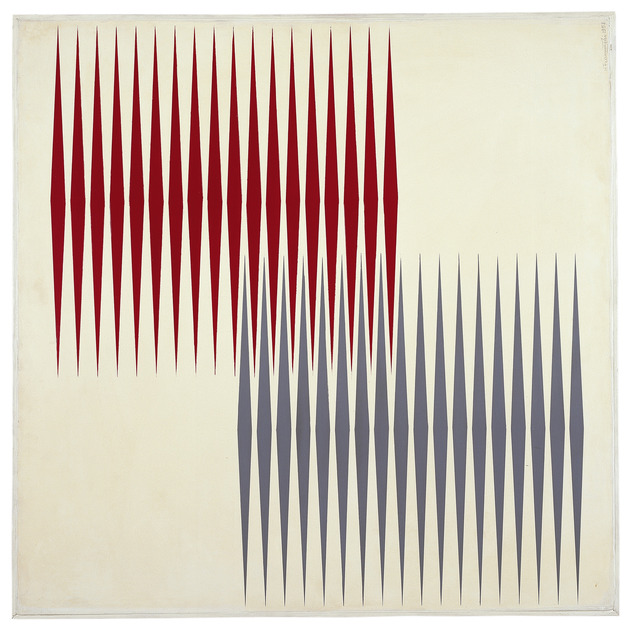

Rubén Núñez was a pioneer of kinetic art in Venezuela. His Op-art pieces are among the earliest in Latin America and were exhibited in Paris in 1951. He realized his seminal optical investigations as a member of the Dissidents Group, whose members included Carmelo Arden Quin and Alejandro Otero. Núñez acknowledged the influence of Piet Mondrian and was a versatile artist, producing moving images while simultaneously working in the field of applied arts, notably with glass. Later in his career, he focused on new technologies such as holographic projections and laser.

Mateo Manaure was one of Venezuela’s most prolific geometric abstractionists in the 1950s. He cofounded Taller Libre de Arte and Galeria Cuatro Muros, which presented the first exhibitions of abstract art in his country. While in Paris between 1947 and 1950, he was a member of the Dissidents group and had a leading role in the defense of hard-edge abstraction. His return to Venezuela propelled geometric abstraction to the level of a national art form. Switching between figuration and abstraction throughout his career, Manaure also engaged with Informalism and was interested in identity issues, often finding inspiration in the Pre-Columbian art of his country. His abstract geometric works for urban spaces in the 1970s have become landmarks of public art in Venezuela.

Carlos González Bogen was one of the most vocal and productive abstract geometric artists in Venezuela during the late 1940s and early 1950s. He belonged to the early wave of pure Constructivist artists and created the largest public abstract-art intervention in the country’s history: the monumental ceiling of the Simón Bolívar modernist building complex in Caracas. In Paris between 1948 and 1951, he was part of the avant-garde group of Venezuelan “Dissidents,” and one of its most articulate voices. An active member of the Communist Party, Bogen adopted Social Realist figuration in the early 1960s and adhered to that style until the end of his life. He is widely considered one of the finest Venezuelan artists of the twentieth century.

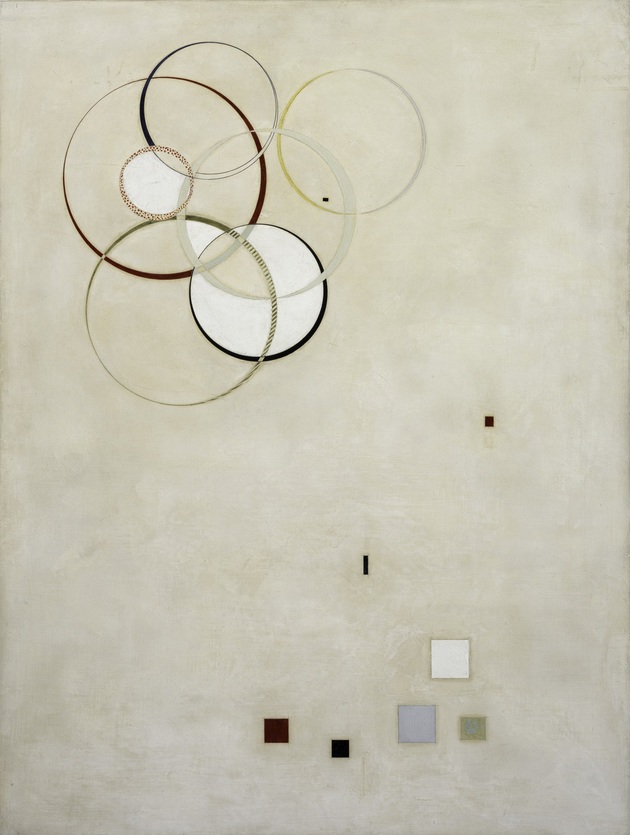

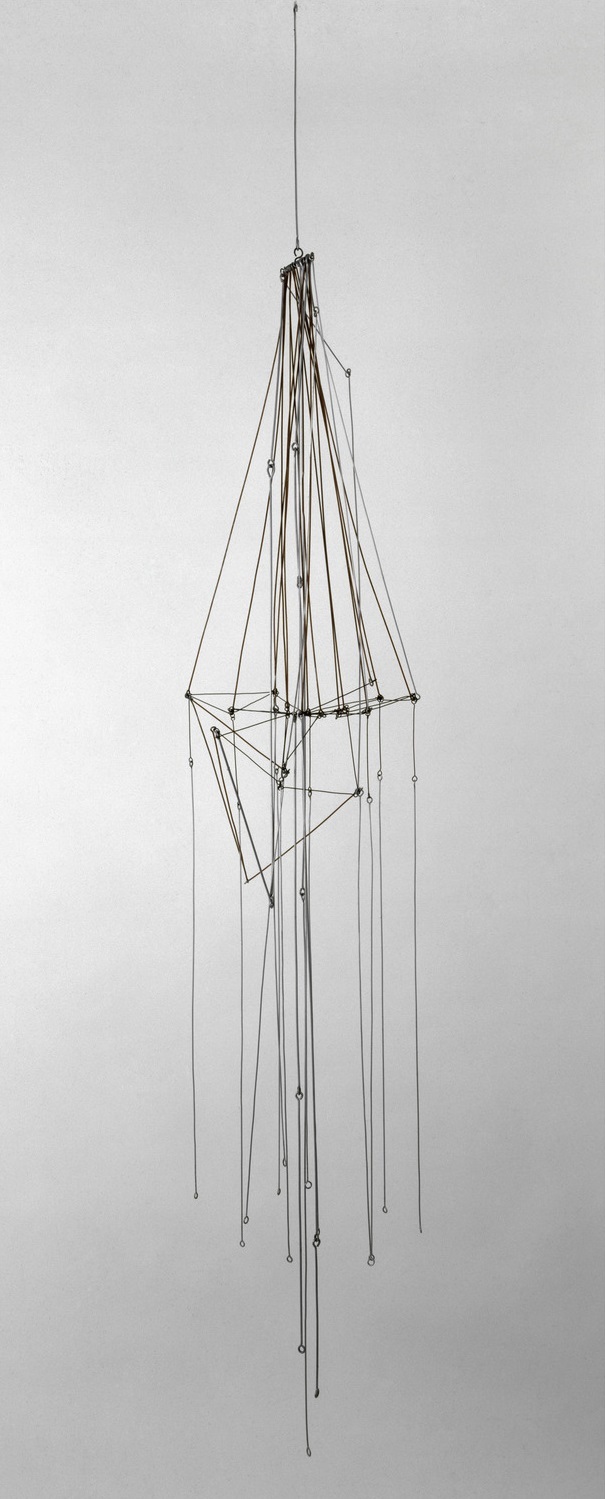

Born into a Jewish family in Hamburg, Gego trained as an architect before fleeing Germany at the beginning of World War II. She settled in Caracas, Venezuela, and worked in an architecture firm until her early forties, when she began to pursue art-making in earnest in close dialogue with her companion, the artist Gerd Leufert. After starting out making gestural landscapes, she developed her signature nonobjective vocabulary, articulated through a radical use of line in sculptures, drawings, and prints. One of the most renowned Venezuelan abstractionists, Gego explored line on its own terms, creating sophisticated, expressive works whose subtle effects generate novel visualizations of space, networks, and motion.

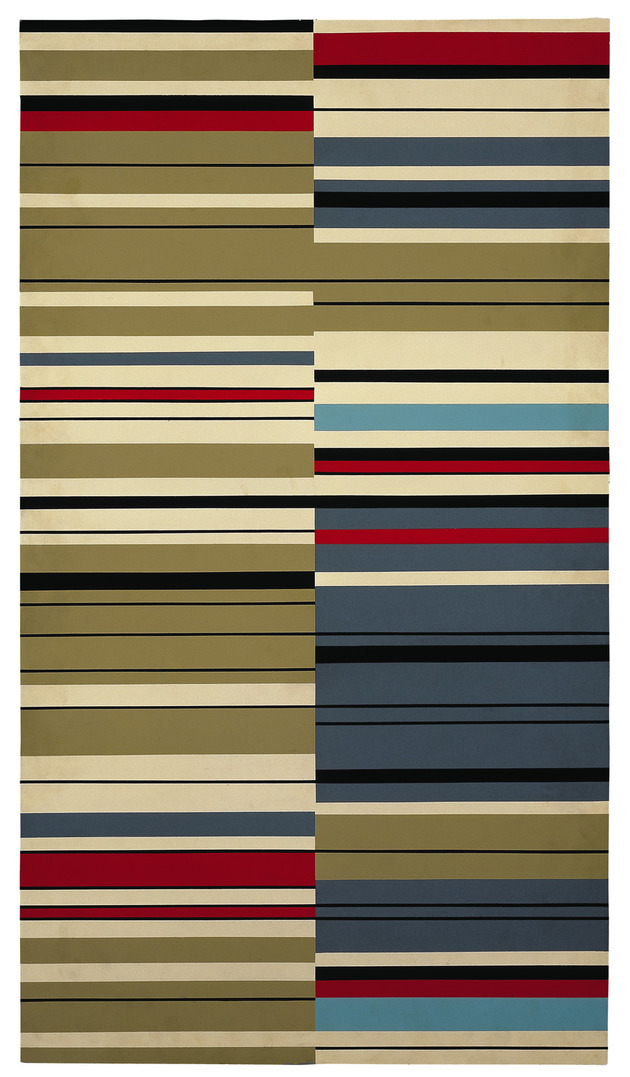

Carlos Cruz-Diez is among the pioneers of Latin American Op and Kinetic art, along with Rafael Soto and Abraham Palatnik. His works are characterized by chromatic modulations produced in conjunction with the viewer’s movement and environmental light conditions. For Cruz-Diez, color emerges through optical effects to create an ephemeral, dynamic, and existential experience that is constantly transformed by light, time, and space and depends on spectators’ participation.

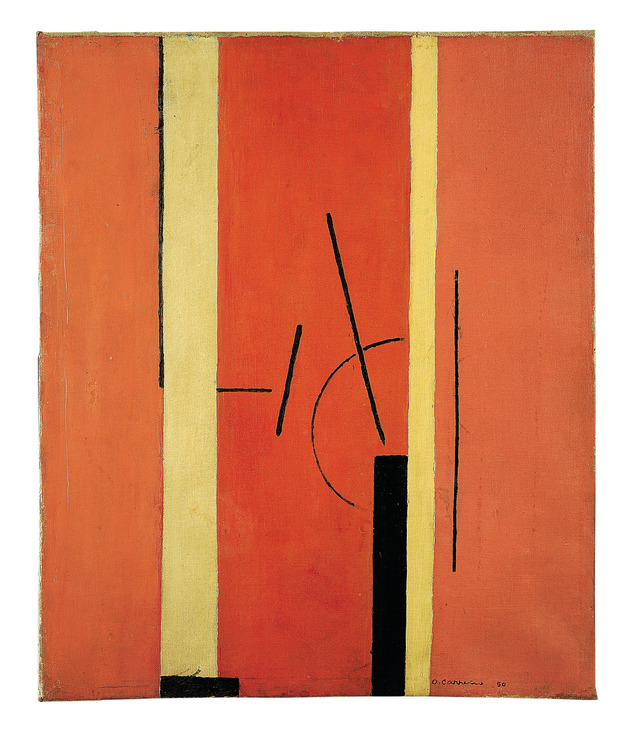

Omar Carreño was a pioneer of Constructivist art in Venezuela. He began his career as an academically trained figurative painter and was among the first Venezuelan artists to produce transformable works—manipulable, multi-part structures that invite the viewer’s active participation. He referred to these pieces as “polípticos” and continued to develop them throughout his career, later introducing the use of electricity. Except during a brief engagement with Informalism, Carreño remained committed to geometric abstraction until the end of his life and today is considered among Venezuela’s leading exponents of non-objective aesthetics.