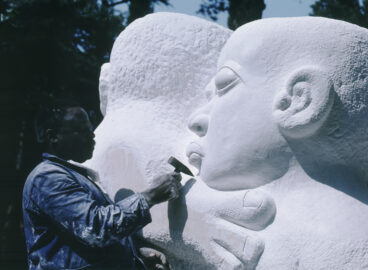

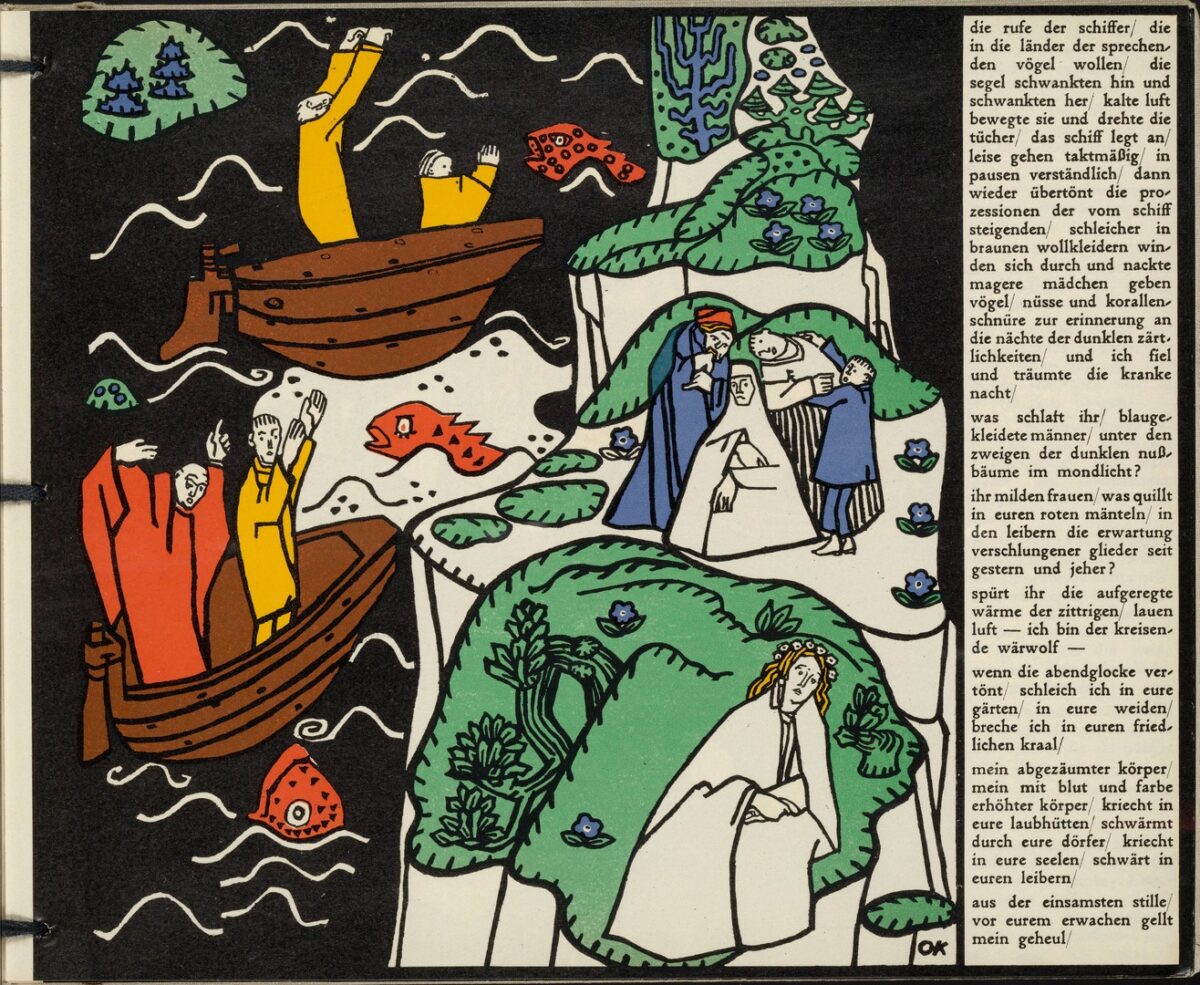

In 1907, Oskar Kokoschka (1886–1980) was commissioned to create an illustrated fairy tale for the children of Fritz Waerndorfer, founding member and financial supporter of the Wiener Werkstätte, Vienna’s premier design workshop. In Die träumenden Knaben (The Dreaming Boys, 1917), Kokoschka produced a haunting narrative poem about the awakening of adolescent sexuality, set on distant islands, far removed from modern city life and bourgeois society. His meticulously crafted text draws on familiar tropes from classical and contemporary literature, including works by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Viennese writer Peter Altenberg. While nostalgia is an essential trope of the Romantic period, Kokoschka’s work subverts this emerging canon. His work transforms what should have been a Romantic-style evocation of nostalgia and passes traditional wisdom through myth into a critical dismantling of such a gesture. The designs in the artist’s lithographs exemplify the prevalent decorative style of fin de siècle Vienna, showcasing his adept integration of various “primitivist” trends in European art. This is evident in Die träumenden Knaben’s cloisonné-like outlines, unconventional perspectives, and flat color planes.

Aside from the aspiration to awaken emotions across a vast geography, Romanticism was hardly a united cultural movement. Poets and writers such as Alexander Pushkin in Russia and Lord Byron in Britain were immersed in rethinking histories of imperial conquests and state-building. The emerging heroism of national liberation movements after the collapse of Napoleonic imperialism in Greece, for example, served as the utmost inspiration for Romantic literary mythmaking. Creating poetry out of the heavily imagined past while weaving new mythologies through it as a powerful embodiment of the Romantic style. Goethe asserted that “the highest lyric is decidedly historical,” alluding to the power of synergy between fact and fiction in shaping the ideological foreground of discourse through literature.1Galvano Della Volpe, Critique of Taste, trans. Michael Caesar (London: New Left Books, 1978), 126. In the age of economic rationalization, Romanticism stood as a mystic guard of the unyielding power of subjective imagination. Applied to actual historical narratives, it became a powerful tool in constructing political imaginaries.

In 1818, Lord Byron published Mazeppa, a narrative poem introducing Hetman Ivan Mazepa (1639–1709), a political leader of borderland Ukraine who, a century before, had stood at the fateful historical intersection between the warring Swedish and Russian Empires. Undoubtedly, Hetman Mazepa played a crucial role in the war as custodian of a borderland; however, the exact details of his actions are disputed, leaving an empty vehicle for Romanticist imagination. Mazepa is known for changing allegiances, but the precise circumstances of his shifts are apocryphal. He initially supported Russian emperor Peter I (r. 1682/1721–25) but later defected to the side of Swedish king Charles XII (r. 1697–1718). As little is known about Mazepa from historical sources, Byron had the freedom to experiment with sentimental inventions. In Mazeppa (1819), he portrays the hetman (commander) as a youthful hero, a romantic soldier of fortune famous for his aesthetic tastes, and a supporter of arts and culture. Ten years later, Russian Golden Age poet Alexander Pushkin published, like a delayed “rhapsodic battle” with Byron, his own interpretation of Mazepa’s story in Poltava (1828–29). In Pushkin’s poem, the hetman is portrayed as an ailing traitor of the Russian Empire, a ridiculous and horrible old man.

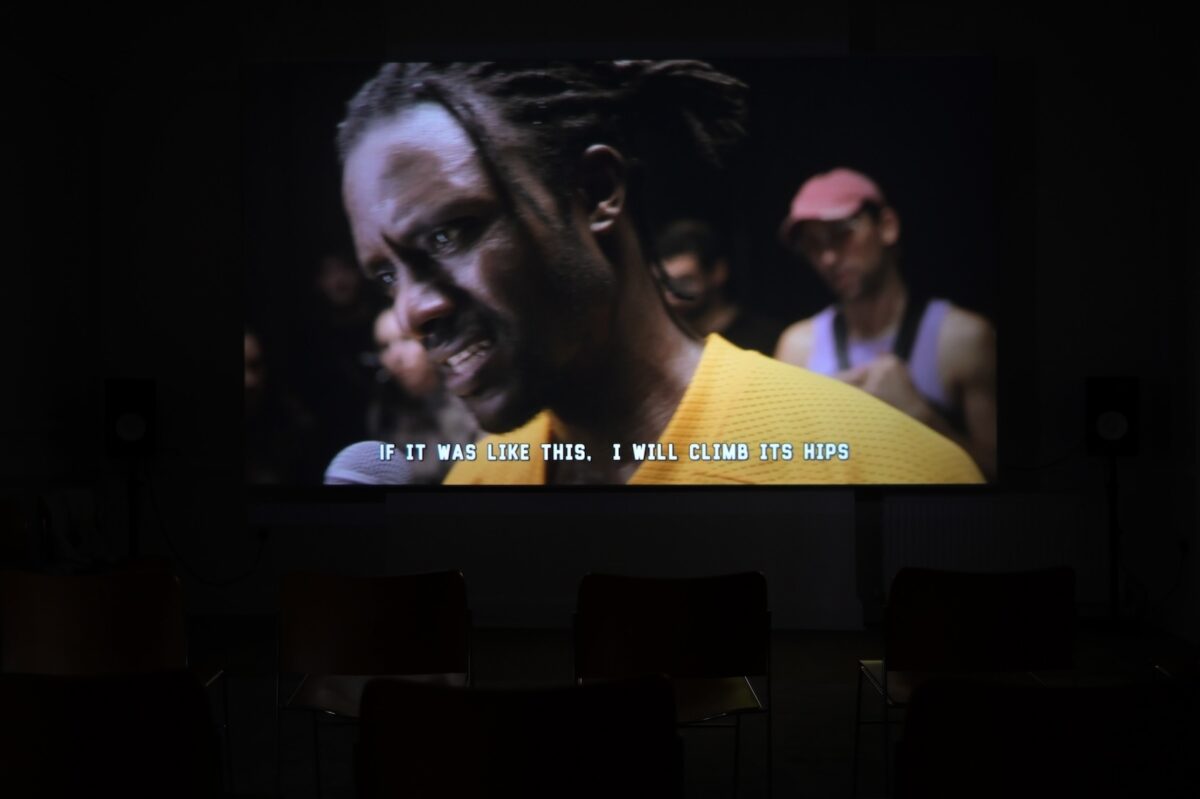

Ukrainian artist Mykola Ridnyi (b. 1985) has revived the Romantic-age rivalry with a transhistorical twist, revealing how a core stylistic element of Romanticism lingers in contemporary times, namely in the form of an uncompromising agonism. In his video work The Battle Over Mazepa (2023), commissioned jointly by Pushkin House in London and John Hansard Gallery in Southampton, Ridnyi cast spoken-word artists from around Europe to stage an actual rhapsodic narrative battle of rendering and creating subjective takes of Byron’s and Pushkin’s stories. Referred to by the artist as a “rap battle,” the medium is more akin to the practice of the ancient Greek aoidoi (Attic bards or storytellers) who performed poems as narrative stories. While Ridnyi bridges the ancient and contemporary forms of weaving the narrative, Byron’s and Pushkin’s respective storytelling can be considered “a narrative digression,” or parékbasis in Attic, the important bardic strategy in which the narrator intentionally alters details of the story to deliver a moral, ethical, or political “lesson” to the audience while retaining recognizable fundamentals.

Ridnyi’s video reveals the transhistorical nature of political agonism by layering ancient tradition, Romantic source material, and contemporary style. The concept of agonism is rooted in the works of Nazi political scientist Carl Schmitt, who insisted that binary conflict is a natural state of the political animal—and that winning by any means is the only way to ensure survival.2See Carl Schmitt, The Concept of the Political (1932; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007). More recently, political theorist Chantal Mouffe has developed agonism into a more general paradigm of looking at conflict as a healthy state of affairs and mitigating it as a fundamental task of the political system. Mouffe has criticized the possibility of post-conflictual mediation societies, which she thinks only serves to bury the conflict temporarily and, in effect, to create a ticking time bomb. The essential point here is that while agonism is discussed as natural, assigning roles in a friend-enemy distinction is highly volatile depending on the evolution of the context.3See Chantal Mouffe, The Return of the Political, Radical Thinkers (1993; London: Verso, 2020 revised edition).

In casting spoken-word artists as contemporary bards, none of whom were previously familiar with Byron’s Mazeppa or Pushkin’s Poltava, Ridnyi focused on the diversifying representation of those who contemporaneously weave the historical narratives anew, indicating the enduring relevance of re-rendering stories in modern political and culture wars. Before filming, the bards participated in a workshop led by Susanne Strätling, professor of Eastern European studies at Freie Universität Berlin. Mediated by Ridnyi and Strätling, the artists read Mazeppa and Poltava, and each formed a subjective interpretation of Mazepa’s character based on the literary portrayals—choosing their side (for or against the hetman) in the process. Mazepa served as source material in the agonistic setup for the artists in the video—reminiscent of contemporary tendencies of turning cultural memory into a site of an emotive battle of subjective truisms.

The 20-minute-long film, shot in 4K in a Berlin warehouse on a hot summer day, showcases rhapsodic battles against a pitch-black background. This staging recalls Kokoschka’s illustrations in which the baroque complexity of the Romantic backdrop is nullified by the flat, color-saturated figures set against a black background, highlighting their presence and accentuating the agonistic tension between them. In the film, the camera moves between pairs of poets performing the twisted verses inspired by Byron’s and Pushkin’s texts. The action is framed by chanting extras, who evoke an ancient theater choir. These singers carry meme-like banners and flags akin to the frequently posted short opinion statements on social media.

In their respective epochs, Kokoschka and Ridnyi each subverted the aesthetics of Romantic storytelling: They stripped the beautifying surroundings and focus on the essence of the brutal agonistic argument in place. They effectively challenged not only Romanticism as a literary and artistic movement but the act of romanticization of anything—and this leads to a fundamental questioning of the attitudes of the material and immaterial cultural heritage in the past, present, and future. The transtemporal relevance of this comparison stands by the essential question that pierces through the epochs: Are we continuing to romanticize Romanticism itself?

For the exhibition curated by Elena Sudakova at Pushkin House, Ridnyi developed a newspaper-like leaflet that presents a Wikipedia-style introduction of Mazepa’s character, somewhat mocking the possibility of arriving at truth through describing him. It is framed similarly to Kokoschka’s illustrations. Both artists emphasize temporality rather than constancy, the relativism in the narrative construction. Visitors to the exhibition could take home a copy of the one-page agitprop publication. Ridnyi’s video enlivens the message with new media energy and breathes dynamism into a rhetorical battle.

While Kokoschka challenged the use of folklore in reaffirming traditional values, Ridnyi has refused to take a side, to choose one or the other portrayal of Mazepa as more probable and outrightly highlighted the subjective nature of any possible reading and interpretation of the character. Both artists’ works boldly subvert the romanticization of generic conventions, “bastardizing” their elevation to the level of sanctity. They did not need to invent the methodology from scratch; rather, they employed ancient techniques of narrative speculation from rhapsodists of the deep past. With equally vivid energy, both challenged the norms of accepted discourse that preclude conformism to authorial position or its binary, agonistic opposition. Kokoschka dove into the psyche of his adolescent readers, offering them introspective agency in the face of the demanding regulations of the world around them. At the same time, Ridnyi emphasizes the artificiality of the restriction in the political stances on Hetman Mazepa offered to the passive spectator as if from a menu of acceptable positions. The works differ in style, but they are comparable in their seeming attempts to subvert the essence of the respective narrative in affirmation of the sociopolitical order and naturalness of agonism.

The creative impulse is comparable to how the ancient Greek rhapsodists, for example, wildly rendered folk stories and their characters. We have so many versions of Heracles, Dionysus, and other mythological characters, sometimes radically different depending on the author narrating them. Paradoxically, the creation of a myth was a demystifying gesture. The multiplicity of possible versions and the constant introduction of new portrayals of characters and new readings of storylines prevented them from fossilization and invited the dynamic approach to the social identity–affirming lore. The eternal and static become impossible, while dynamism and change characterize the necessary reaction to essential change with the constant transformation of the community. Unlike the Romantic search for fundamental, unchangeable wisdom and permanent cultural codes embedded at the beginning of time, the rhapsodic attitude to rendering the story invites the propositions of reformation, vital critique, and opposition. In this spirit, Pushkin and Byron can be seen as creators of entirely different characters in parallel literary realities. This assumption counters the historizing attitude of Romanticism and redefines the scheme of approaching storytelling at large as narrative speculation or a field of essential, dynamic digressions.

Shaping collective political memory is essential to legitimize contemporary forms of universal imperialism and its primary adversary—a particular nationalism. While the weaponization of cultural heritage in the political struggle is ubiquitous, Ridnyi’s film epitomizes the critical function of narrative digression, namely subversion. “Subversion,” rooted in the Latin verb subvertere (to overthrow), refers to a process by which the values and principles of a system are contradicted or reversed to sabotage the established social order and its structures of power, authority, tradition, hierarchy, and social norms. Kokoschka and Ridnyi have approached subversion from opposite ends, but they both aimed to achieve the same effect of critical confusion in their respective audiences. Kokoschka challenged his client’s expectations by subverting the fairy-tale genre as a vessel in which to preserve bourgeois norms and values and instead focusing on the realness of the experience of growing up. This strategy sparked effective intergenerational agonism instead of creating repulsion for the abnormal and a reverence for conservative ideals—as was desired by the party that commissioned the work—thereby introducing a speculative artistic agency. Ridnyi has thrown off presumed determinacies of the correct or incorrect political position by subverting agonism itself, equalizing the perceived real and the possible speculative. While the approaches to the subject differ, both artists have focused on subverting the status quo by addressing the normalized in a way “that is just human nature” agonism. They transform the gesture into effective and potent criticism by making the sociopolitical construction and conditions of agony visible, registrable, and estranged.

Ridnyi’s video challenges the audience to step back from choosing sides—and to focus on dangerous oversimplifications as a fundamental source of naturalizing fiction. The Battle Over Mazepa, the first video in a planned trilogy, restages Romantic agonism and demonstrates its actuality in the present—against the backdrop of Russia’s war against Ukraine. It also reveals the tendency of contemporary art to reaffirm the subjective, oversimplified battlefronts through aestheticization—as in the case of Romantic legacies. Like the meme-banner holders in the video, the artist with a political agenda draws the frontiers to the agonistic battle lines, reaffirming the distinction between friend and enemy.

As David Graeber and Nika Dubrovsky argue, Romanticism sanctified the nation-state as the church waned.4See Nika Dubrovksy and David Graeber, “Another Art World, Part I: Art Communism and Artificial Scarcity,” e-flux Journal, no. 102 (September 2019), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/102/284624/another-art-world-part-1-art-communism-and-artificial-scarcity/. It legitimized the state as an absolute arbiter of ethical and moral judgement. As such, it materialized a political imaginary. While French philosopher Auguste Comte insisted on the “rationalization” of society through the nation-state, Romanticism in fact remythologized society anew.

The work of Kokoschka critically addresses the emerging bourgeois conservatism, which aimed to rearrange society’s new boundaries of restrictions as the power of the church vanished—and in that, to tighten the screws on the imagination of possible alternatives from the early childhood period. In challenging his commissioner’s intention so radically, Kokoschka revealed the intention behind the supposedly apolitical gesture of producing a piece of “edutainment” (educating entertainment) for children. Ridnyi, in his interrogation of our permacrisis-branded contemporaneity, spearheads our time’s burning ontological cleavage—normalization of the subjectivity of political agonism, in which the temporary arrangements and interpretations are communicated by power and perceived by the public through the lenses of multiple media channels as natural, eternal, and unchanging. This is among the feeders of the resurgence of new fascisms and other forms supposedly abandoned by the “never again” humanism’s progress, abominations as the solution offered is “final” and “simple.” The Wikipedia-style leaflet in the exhibition at Pushkin House and the one-line-slogan carriers in the video embody the rising number of these agents of further naturalization of agonistic battle.

The problems Kokoschka’s and Ridnyi’s works address intend to reaffirm the stance of historical truism beyond critique, nullifying or conveniently ignoring the context in which it emerged and removing it from the contested speculation space. Such conservative discourse contributes to the problem of “romanticizing Romanticism”—not actively challenging its positionality within “the greatest of eras” and as the source of nostalgic pride—which continues to emphasize the ethereal materiality of ghosts from the past. At the same time, it naturalizes and fixates as permanent the dynamic boundaries of agonistic struggles, presenting figures and ideas about the good and the bad as ontological categories, though they are, in fact, products of the sociopolitical context of their time and their power relations. The subversion and “bastardization” of Romantic tradition through critical speculation, as seen in Kokoschka’s drawings and Ridnyi’s video, show us a potent example of shaking up normality at a moment when reality starts to appear everlasting, futureless, and disjointed from its surroundings. Both works, though separated by age, demonstrate a successful multimedia address of the transhistorical challenge. Amplifying the messages conveyed in these works and further igniting the spread of their approaches is relevant in any time—but specifically in the present.

- 1Galvano Della Volpe, Critique of Taste, trans. Michael Caesar (London: New Left Books, 1978), 126.

- 2See Carl Schmitt, The Concept of the Political (1932; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007).

- 3See Chantal Mouffe, The Return of the Political, Radical Thinkers (1993; London: Verso, 2020 revised edition).

- 4See Nika Dubrovksy and David Graeber, “Another Art World, Part I: Art Communism and Artificial Scarcity,” e-flux Journal, no. 102 (September 2019), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/102/284624/another-art-world-part-1-art-communism-and-artificial-scarcity/.