In the third and final part of this multi-section essay, art historian Ksenya Gurshtein addresses OHO Group’s work in the year 1970. Consulting the MoMA Archives, she highlights and expands upon connections between the Slovene conceptual artists OHO Group and one of the Museum’s most well-known exhibitions, Information of 1970. Archival materials from Information were on display in the fall 2015 exhibition Transmissions: Art in Eastern Europe and Latin America, 1960–1980.

1970: Intercontinental Group Project America-Europe and beyond

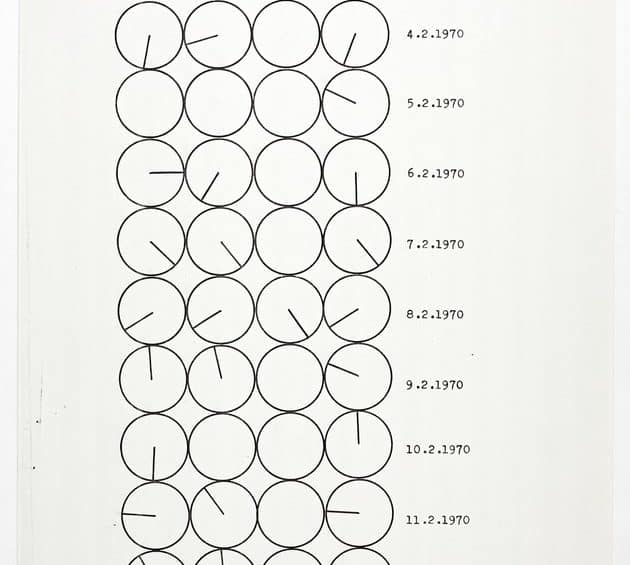

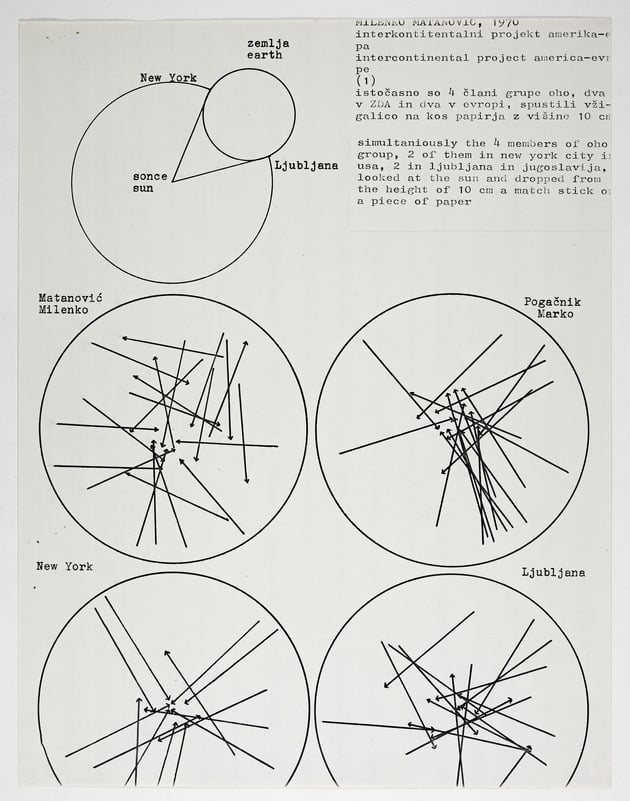

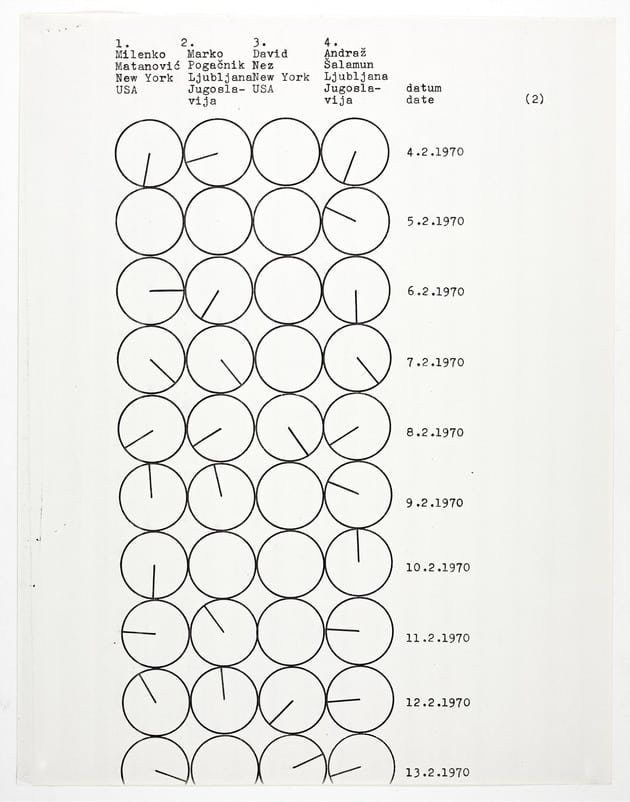

In February of 1970, partly in preparation for Information, which was scheduled to open in July, Nez and Matanović traveled to New York. The trip became an occasion for creating works dealing with the ultimate invisible (and putative) force—telepathy. Recorded only through a set of diagrams, the Intercontinental Group Project America-Europe speaks to OHO’s growing interest in completely merging art and life, in exploring its own internal dynamics, and in the immaterial or non-tangible outcomes of the artistic process.

Created in two versions, Intercontinental Group Project America-Europe asked, when Nez and Matanović were in New York and Pogačnik and Šalamun in Ljubljana, whether telepathic connection was possible. In Pogačnik’s version of the project, the four OHO members drew lines into identical paper grids at the same time; in Matanović’s version, illustrated here, each of the four, at the same time, recorded the position of a match dropped onto a sheet of paper while looking into the sun. Examining the diagrammed results of both projects suggests for the most part that the four men did not have telepathic abilities, though occasional coincidences do leave some room for doubt. Ultimately, whether the results of their actions on two continents are similar is beside the point—the design of the project ensured that OHO members were thinking of each other at the same time, in effect transcending their separation across space and time zones. Even if this project did not produce actual telepathic transmission of information, it activated a sense of powerful connection, a kind of emotional telepathy.

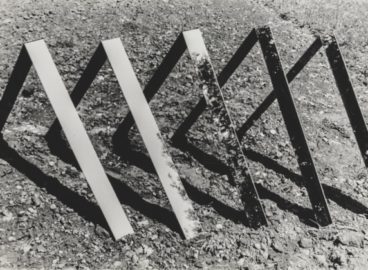

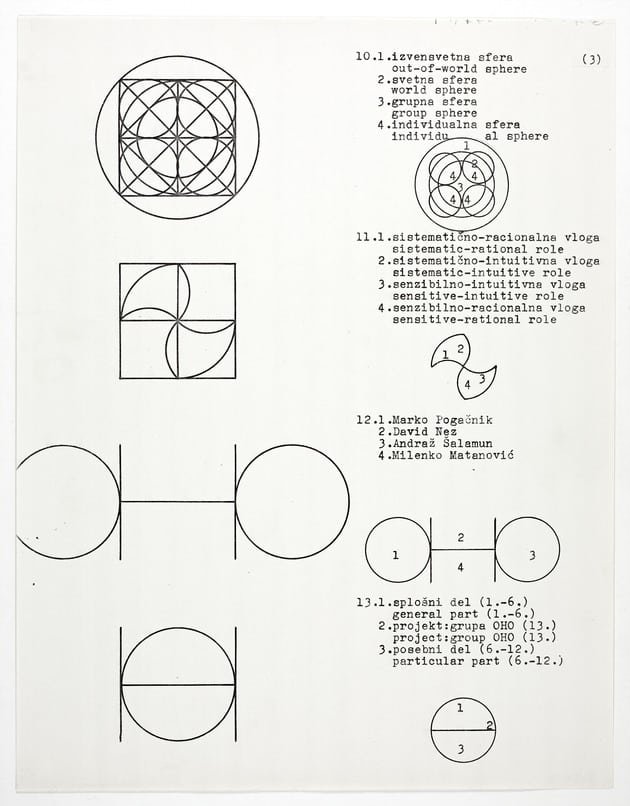

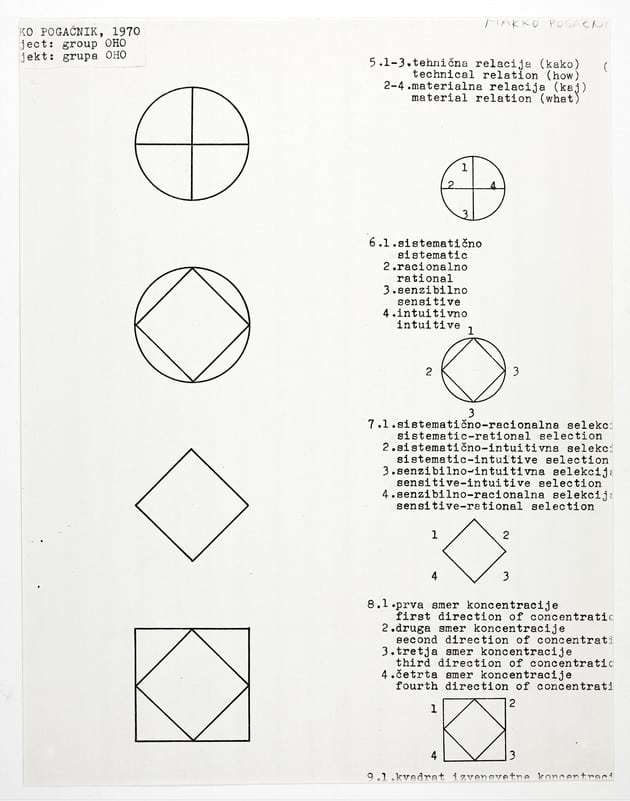

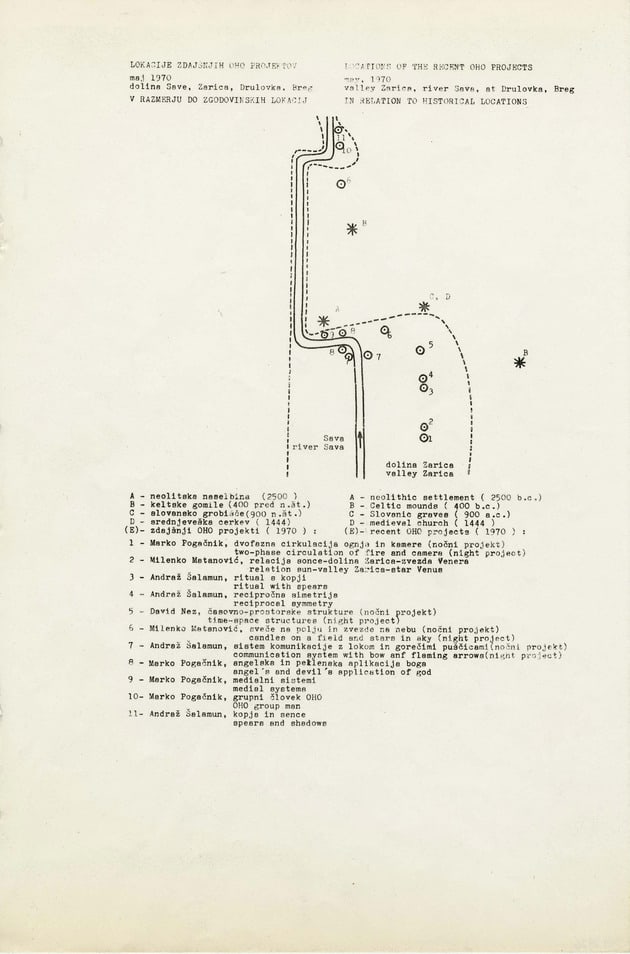

Three more OHO artifacts from 1970 included in Information document the group’s further retreat into nature and shift toward shaping and visualizing its internal identity and dynamics. Pogačnik’s Project OHO offered a series of progressively more complex diagrams based on the group’s name, which located the group within its own cosmology and envisioned complex interrelationships between its members.1Marko Pogačnik: “In the first place, the Project OHO is about the cosmology of OHO as a name based on the alogical structure of squaring the circle (two circles and a square in the middle); secondly, it is also about the archetypal division of roles between the four of us in the OHO Group. The premise is that all primitive cultures knew the principle of their cosmic origin. If OHO is to be constituted as a holistic culture, it must develop its cosmology. I set about doing this as a project. I noticed that the name OHO consisted of two circles (O) and two squares (H). The circle and the square represent the two polar principles, the female (O) and the male (H) ones. The group is in fact a synthesis of both these principles, and the synthesis occurs on the basis of the unsolvable mathematical problem of squaring the circle. I observed the ways in which each of us approached their respective projects, and divided between us the four roles contained in the name of the OHO Group on the basis of my observations.” See Beti Žerovc, “The OHO Files”: Interview with Marko Pogačnik.” Art Margins Online (24 August 2011). A map documenting the locations of the ephemeral actions and installations OHO created in the Zarica Valley in May of 1970 relates the artists’ works to the locations of older sacred sites, ranging from a Neolithic settlement to a medieval church; the map thus superimposes the mental mapping of time over the physical mapping of space. In one of the mapped projects, Andraž Šalamun’s Night, Bow and Flaming Arrows, four participants communicated across a river (two on each bank) by shooting flaming arrows either vertically or horizontally in a predetermined sequence. This work, along with several others of the mapped Zarica Valley projects, prefigured the so-called schooling that the group undertook in the summer of 1970, moving even further from the creation of documentable artistic projects and devising daytime and nighttime exercises meant, according to Pogačnik, to find a way of “working both with the body and with spiritual dimensions” and “to develop an art that would enable people to come to know themselves and experience the profound dimensions of space at the same time.”2Marko Pogačnik: “The schooling in Čezsoča, like the Zarica Valley projects, was about searching for a way to continue working both with the body and with spiritual dimensions. We wanted to develop an art that would enable people to come to know themselves and experience the profound dimensions of space at the same time. Understandably, we needed to test everything on and by ourselves first. The schooling was divided into daytime and nighttime exercises. Daytime exercises comprised such things as developing various forms of group walking through the countryside or town, which resulted in experiencing space physically and spiritually. An example of a nighttime exercise would be contemplating the starry sky. We later transformed this experience of schooling into a commune.” See Beti Žerovc, “The OHO Files”: Interview with Marko Pogačnik.” Art Margins Online (24 August 2011).

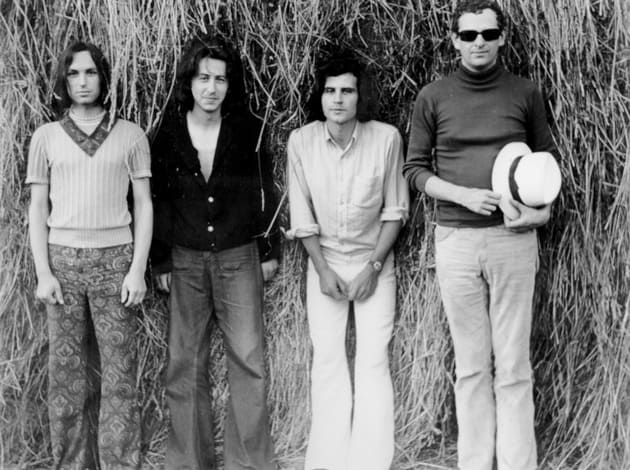

Chronologically, the last photographs in the MoMA Archives are the sequence in which the group members posed with Walter de Maria in August 1970. OHO members had long been interested in permutation as a conceptual premise, and this group of five photographs shows the different possible combinations of four people that can be derived from a group of five. The photographs are more significant, however, because they mark a key moment of choice in OHO’s thinking about its future. As Pogačnik has put it: “The group consciously and deliberately self-abolished, to enable the transition to the next creative stage. The alternative we considered for a while was entering the international art scene professionally. When Walter de Maria came to Kranj to visit Marika and me, he tried to talk us into that, on the grounds that we could rank high, as it were, among conceptual groups internationally. In the end, though, we decided on a completely different step, based on our group spiritual schooling.”3See Beti Žerovc, “The OHO Files”: Interview with Marko Pogačnik.” Art Margins Online (24 August 2011). Comparing the reminiscences of all four of the former OHO members paints a more complicated picture of why the artists parted ways—the reason Pogačnik mentions coincided with Yugoslav art officials’ refusal to help the group show internationally, even as the interests of the still very young group members began to diverge, with three of the four unwilling to dedicate themselves to founding a commune.4Interviews with all four former OHO members conducted by Beti Žerovc and published in 2011 and 2013 by ArtMargins Online can be found here.

The group’s decision to disband in order to find ways to merge art and life more fully can be seen as yet another facet of its belonging to the global Conceptualist tradition. That decision can be compared, for instance, to the exit from the art world in 1972 of Seth Siegelaub, the godfather of New York Conceptualism, or the departures in the late sixties and early seventies documented in the 2004 exhibition Kurze Karrieren (Short Careers) at Vienna’s MUMOK, in which several of the artists represented (including OHO) left art behind because of their unwillingness to participate in the art market, fit into institutional constraints, or participate in activities that lacked direct social impact.

OHO’s work as an artist collective had an important impact on Yugoslav culture at the time and resonates in Slovene culture up to the present day. Even though the group ultimately retreated into nature and the inward-looking utopia of a commune (such inwardness being a common fate of many attempts at utopia in postwar Eastern European art), it was able to create in a crucial historical moment and despite limited means, both physical and discursive spaces of free expression that could occupy anything from a newspaper page to a public park. In these spaces, the group was able to bring into a public arena intellectual tensions that replicated, in miniature, the tensions between political engagement and withdrawal, systematicity and chaos, irony and deep spirituality, and obsession with and distrust of language, that were happening within the global art scene on a much larger scale.5I have written more about the internal tensions of OHO’s work in Ksenya Gurshtein, “OHO / An Experimental Microcosm on the Edge of East and West,” in Christian Höller, ed., L’Internationale. Post-War Avant-Gardes Between 1957 and 1986. More information can be found here. Finally, OHO influenced the generation that followed it, including the artists associated with the Student Cultural Center in Belgrade, which became another important space for the production of “new artistic practice, the dematerialization of the art object, post-objective art, the art of behavior, and new-media art…that stemmed from the art of rejection from the end of 1960s.”6See Jovana Stokic, “Beuys’s Lesson in Belgrade,” post: notes on modern an contemporary art (25 November 2014). There is also deep inspiration to be found in the group members’ willingness to take OHO’s lessons outside the art world and to apply them to such mergings of art and life as community-building projects (Matanović), art therapy combined with continued visual art practice (Nez), and earth-healing (Pogačnik). Indeed, of the four members of the group, only Andraz Šalamun returned entirely to the traditional medium of painting after OHO. The artists’ later stories are not, of course, part of the Information archive, but the archive remains invaluable for understanding what came next.

This is the third and final part of a multi-section essay on OHO Group. Read Part 1 here and Part 2 here. It will be complemented by images of newly digitized materials by OHO Group from the MoMA Archives as well as the first English translation of the 1969 interview between OHO Group members Milenko Matanović and Tomaž Šalamun. Read the interview here.

- 1Marko Pogačnik: “In the first place, the Project OHO is about the cosmology of OHO as a name based on the alogical structure of squaring the circle (two circles and a square in the middle); secondly, it is also about the archetypal division of roles between the four of us in the OHO Group. The premise is that all primitive cultures knew the principle of their cosmic origin. If OHO is to be constituted as a holistic culture, it must develop its cosmology. I set about doing this as a project. I noticed that the name OHO consisted of two circles (O) and two squares (H). The circle and the square represent the two polar principles, the female (O) and the male (H) ones. The group is in fact a synthesis of both these principles, and the synthesis occurs on the basis of the unsolvable mathematical problem of squaring the circle. I observed the ways in which each of us approached their respective projects, and divided between us the four roles contained in the name of the OHO Group on the basis of my observations.” See Beti Žerovc, “The OHO Files”: Interview with Marko Pogačnik.” Art Margins Online (24 August 2011).

- 2Marko Pogačnik: “The schooling in Čezsoča, like the Zarica Valley projects, was about searching for a way to continue working both with the body and with spiritual dimensions. We wanted to develop an art that would enable people to come to know themselves and experience the profound dimensions of space at the same time. Understandably, we needed to test everything on and by ourselves first. The schooling was divided into daytime and nighttime exercises. Daytime exercises comprised such things as developing various forms of group walking through the countryside or town, which resulted in experiencing space physically and spiritually. An example of a nighttime exercise would be contemplating the starry sky. We later transformed this experience of schooling into a commune.” See Beti Žerovc, “The OHO Files”: Interview with Marko Pogačnik.” Art Margins Online (24 August 2011).

- 3

- 4Interviews with all four former OHO members conducted by Beti Žerovc and published in 2011 and 2013 by ArtMargins Online can be found here.

- 5I have written more about the internal tensions of OHO’s work in Ksenya Gurshtein, “OHO / An Experimental Microcosm on the Edge of East and West,” in Christian Höller, ed., L’Internationale. Post-War Avant-Gardes Between 1957 and 1986. More information can be found here.

- 6