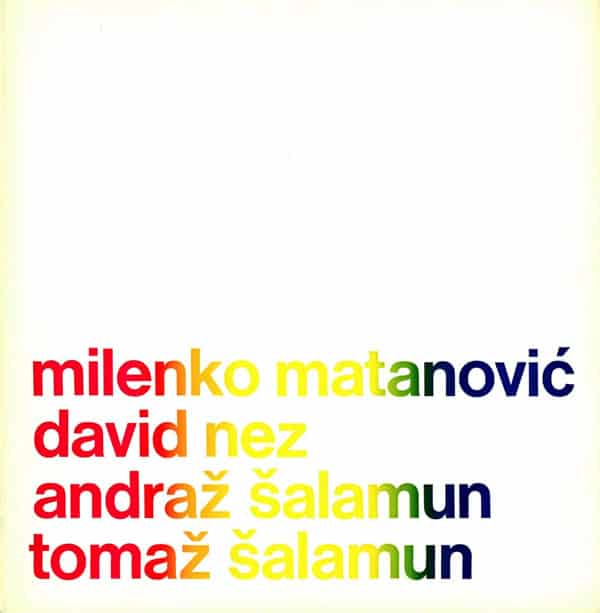

Translated from Serbo-Croatian into English here for the first time by Aleksandar Bošković and Jennifer Zoble, “An Interview with Milenko Matanović and Tomaž Šalamun” was published in the 1969 catalog of the exhibition Milenko Matanović, David Nez, Andraž Šalamun, Tomaž Šalamun that took place at the Gallery of Contemporary Art in Zagreb. The exhibition featured works by Milenko Matanović, David Nez, Andraž Šalamun, and Tomaž Šalamun. Having studied the catalog in the MoMA Archives, scholar Ksenya Gurshtein offers introductory commentary on the interview and exhibition. This primary document appears in conjunction with the multi-part essay “The OHO Group, “Information,” and Global Conceptualism avant la lettre”.

Permission to republish this interview has been generously granted by Milenko Matanović and Metka Krašovec.

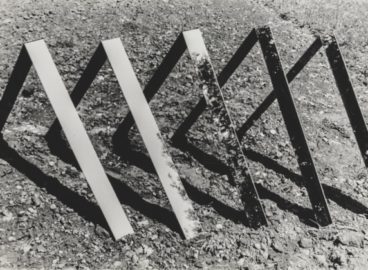

Though his engagement with OHO was short-lived, Tomaž Šalamun played an important role in shaping the group’s artistic trajectory. A poet who had traveled extensively through Western Europe, spent time in Rome with the artists of the Italian Arte Povera, and was working as a curator at Ljubljana’s Moderna Galerija, Šalamun encouraged OHO to congeal by 1969 into a more tightly knit collective of four members (Milenko Matanović, David Nez, Tomaž Šalamun, and Tomaž’s brother, Andraž).1The standard form that each artist was asked to fill out for the Information curatorial files that are now in the MoMA Archives, reveals the extent of Tomaž Šalamun’s travels – in addition to studying in Ljubljana, he had studied in Krakow in 1966, traveled multiple times to Paris since 1959, went to Rome in 1961, 1964, and 1969, and listed visits to Greece, Poland, West Germany, the Netherlands, and Belgium during the 1960s. He listed the start date of his work as a sculptor as 1968 and mentioned living in Rome in 1968 as an experience relevant to his artistic work. Šalamun’s career as an artist was very short-lived, and he did not create new work after 1969, when he held an ill-fated one-man exhibition in the small town of Kranj that was closed by the authorities after one day. He was represented in Information by a work from 1969. The Pradedje exhibition in Zagreb marked this moment of transition; the catalog of this exhibition was one of the first things that Taja Vidmar sent Kynaston McShine.2A copy of this catalog can also be found in the MoMA Archives. A scanned version of the catalogue is available in its entirety here. The installations captured in it (made of bricks, hay, plastic, and an entire salvaged roof) reflect the influence of Arte Povera, combined with a desire to affront and scandalize the museum-going audience. As David Nez has put it, “There was lots of fun and positive energy, that’s what kept us going. There was also the adrenaline rush of pushing the boundaries and being outrageous.3See Beti Žerovc, “The OHO Files”: Interview with David Nez,” Art Margins Online (24 August 2011).

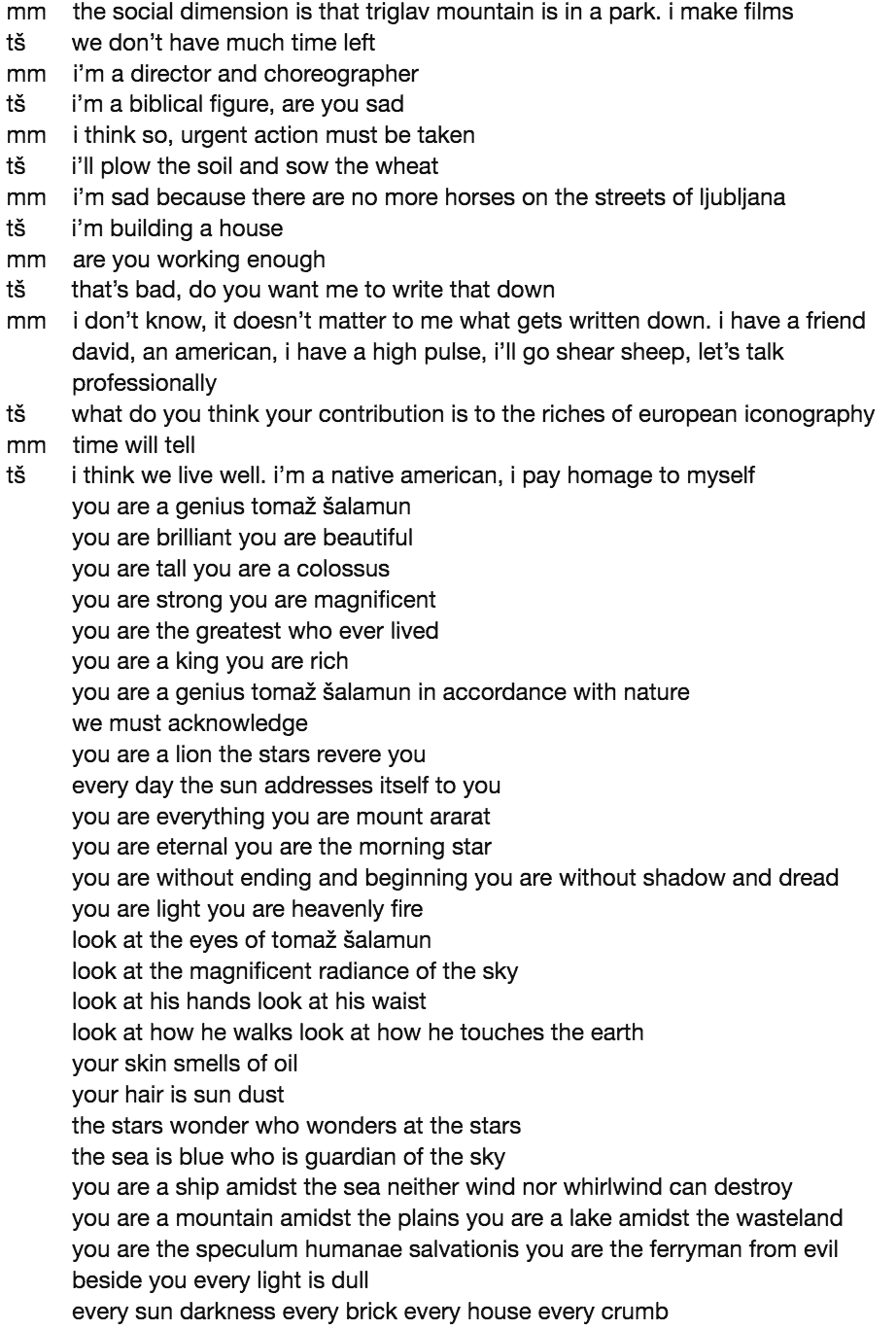

This “interview” captures the outrageousness particularly well. Tomaž Šalamun’s litanies of insults and self-aggrandizing epithets reveal his insistence on having the freedom to say whatever he wanted, which got him in trouble in 1964 when he was briefly imprisoned following the publication of his first poem. According to Matthew Rohrer, “Šalamun …single-handedly ushered in a postmodern exuberance into Slovenian and…Yugoslavian poetry,” combining the “classic seriousness” of the European Modernist tradition with “thumbing his nose at everything, including himself.”4Matthew Rohrer, “Introduction” in Tomaž Šalamun, Poker, translated by Joshua Beckman, 2nd edition, New York: Ugly Duckling Press, 2008, i-ii. Poker was originally published in 1966.

One sees such tension between deference and irreverence towards Art and Culture in the professionally produced Zagreb catalog, where Šalamun and Matanović’s transcribed conversation followed jargon-heavy essays – the critical apparatus necessary to legitimize an artistic practice. One also sees this tension in the unorthodox dialogue itself, which oscillates widely between visions of grandeur on the one hand and “impostor syndrome” anxiety on the other. It also moves between the poles of playfulness and genuine concern with the purpose of one’s activity, as when Šalamun declares, “inside me lies the entire european tradition, i exhibit brick and hay.” Matanović is the more earnest of the two speakers, and his allusion to the Triglav performance (discussed in Part 2 of “The OHO Group, “Information,” and Global Conceptualism avant la lettre”) points to concern with the social impact of OHO’s work: “i’ll exhibit outside, my work has a social dimension…the social dimension is that triglav mountain is in a park.”

— Ksenya Gurshtein

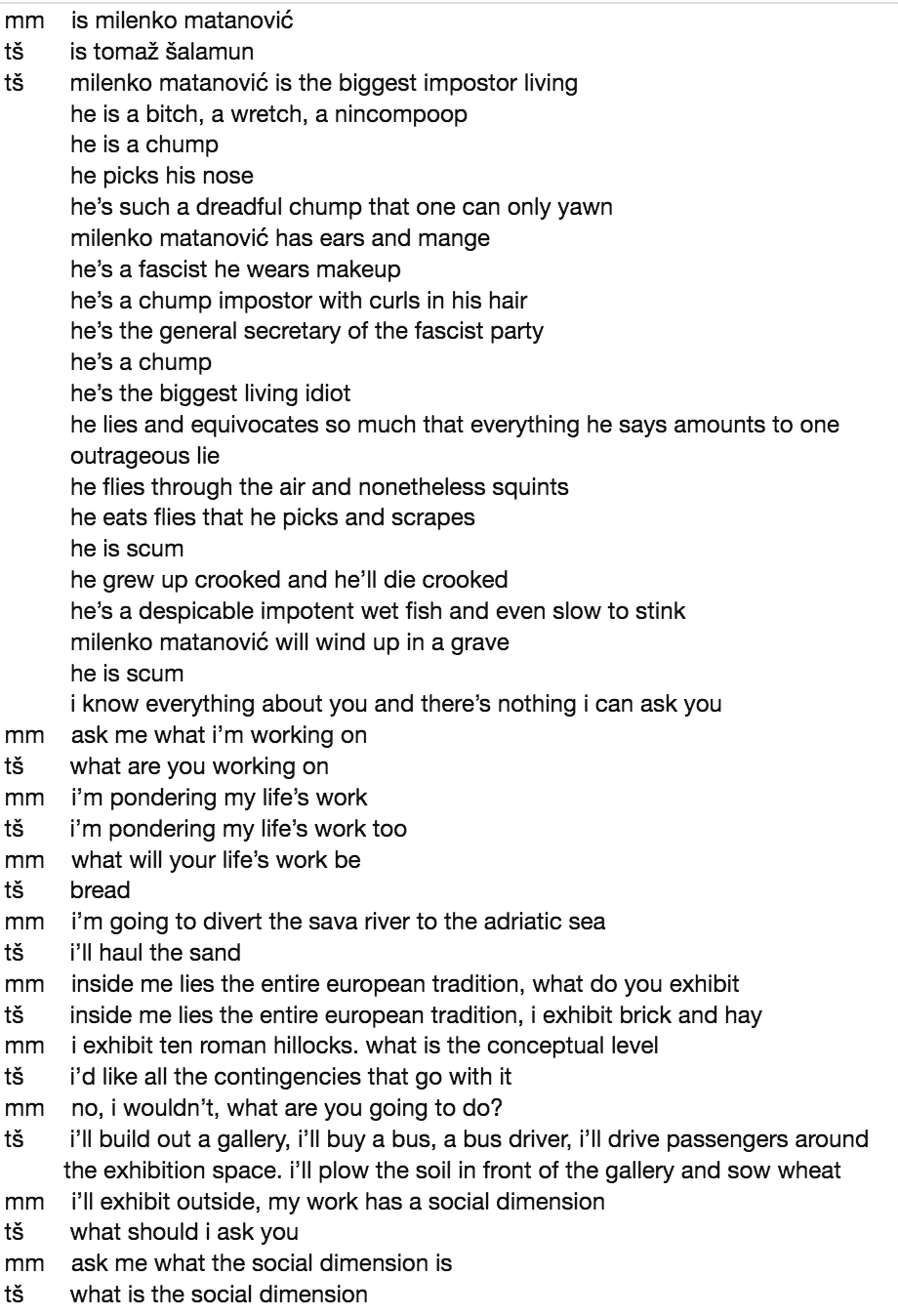

an interview

with milenko matanović

and tomaž šalamun

- 1The standard form that each artist was asked to fill out for the Information curatorial files that are now in the MoMA Archives, reveals the extent of Tomaž Šalamun’s travels – in addition to studying in Ljubljana, he had studied in Krakow in 1966, traveled multiple times to Paris since 1959, went to Rome in 1961, 1964, and 1969, and listed visits to Greece, Poland, West Germany, the Netherlands, and Belgium during the 1960s. He listed the start date of his work as a sculptor as 1968 and mentioned living in Rome in 1968 as an experience relevant to his artistic work. Šalamun’s career as an artist was very short-lived, and he did not create new work after 1969, when he held an ill-fated one-man exhibition in the small town of Kranj that was closed by the authorities after one day. He was represented in Information by a work from 1969.

- 2A copy of this catalog can also be found in the MoMA Archives. A scanned version of the catalogue is available in its entirety here.

- 3

- 4Matthew Rohrer, “Introduction” in Tomaž Šalamun, Poker, translated by Joshua Beckman, 2nd edition, New York: Ugly Duckling Press, 2008, i-ii. Poker was originally published in 1966.