Consulting the MoMA Archives, art historian Ksenya Gurshtein highlights and

expands upon connections between the Slovene conceptual artists OHO Group and

one of the Museum’s most well-known exhibitions, Information of 1970. Archival

materials from Information were on display in the fall 2015 exhibition Transmissions:

Art in Eastern Europe and Latin America, 1960–1980.

In the summer of 1969, while traveling in Germany, MoMA curator Kynaston McShine met Taja Vidmar, an art history student from Ljubljana who was working at the Nuremberg Kunsthalle.1In reading the correspondence in the Information files, I was not able to establish the exact date of the meeting; McShine’s handwritten notes refer to Vidmar as “very nice student met in Nuremberg”; I surmise that Vidmar and McShine met some time in the summer, because the first letter in the correspondence that would result in OHO’s inclusion in the exhibition was dated by Tomaž Brejc, its author, August 15, 1969. McShine was busy preparing Information, which would be MoMA’s big summer show the following year. It was his accidental encounter with Vidmar that accounts for the inclusion of the OHO artists’ group, the only artistic entity from the state socialist part of Europe to be represented in this germinal exhibition that aimed to capture what was a global phenomenon, or, as MoMA put it in the press release for the show, “an international report on recent activity of young artists.”2Given her inclusion in Information, it is reasonable to surmise that Lucy Lippard first encountered OHO’s work at the show and later included the group in her important contribution to the early historiography of “dematerialized” art, Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972. The Czechoslovak artist Petr Štembera is the only other artist from Eastern Europe to make it into that book.

Following their meeting, a correspondence ensued between McShine, Vidmar, and a third participant, a young Slovene art historian (and Vidmar’s husband), Tomaž Brejc.3Milenko Matanović, among others, has acknowledged the Brejcs’ important role for OHO in an interview with ArtMargins Online. “For those of us in Ljubljana, Tomaž and Taja Brejc became important friends and allies. We would often hang out at their home. They had international art magazines, which I would peruse. I am sure that some of those pictures influenced my artistic imagination. In addition, Tomaž, an art historian, was a keen observer of our activities and wrote about them. Opportunities for exhibits were undoubtedly opened up by his writings.” Brejc was OHO’s first chronicler and its ardent promoter, and thanks to his efforts and those of various OHO members, the MoMA archives contain excellent holdings of vintage photographic documentation of the group’s ephemeral work, available in few places outside of Slovenia, where the Moderna Galerija in Ljubljana has the authoritative collection and archive, all of which has been recently digitized.

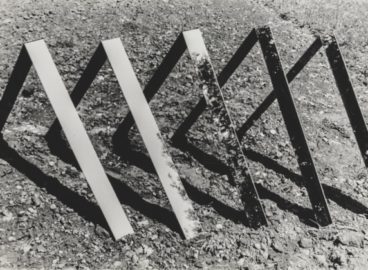

Even in Ljubljana, an uninitiated visitor to the Moderna Galerija may have a hard time figuring out the possible meanings of and relationships between the often cryptic or esoteric works that were created by what was a shifting group of participants (in the brief but intensely creative period of OHO’s existence, its membership fluctuated from a pair of high school friends to an expanded circle made up of writers, visual artists, theorists, and an amateur filmmaker to a group of four members focused on visual art) working across a broad range of media (including printed matter, drawings, objects, films, urban performances, exhibition installations, land art projects, and ultimately experiments in the dynamics of communal life and art). In MoMA’s recent exhibition Transmissions: Art in Eastern Europe and Latin America, 1960–1980, OHO was represented by photographic documentation of works done in nature, which warrant contextualization, particularly because the Information archive mainly represents the last two years of the group’s existence—1969 and 1970—when McShine was putting together his exhibition. Virtually nothing in the archive tells about OHO’s complex earlier history, which began in 1966.4Though the conceptual framing of OHO’s intellectual history offered in this text is my own, my work owes a great debt to the research (including precise chronologies) and analysis offered in the histories of the group written by Slovene art historians Tomaž Brejc and Igor Zabel. For their most extensive texts, see Tomaž Brejc, Oho: 1966–1971 (Ljubljana: Študentski Kulturni Center, 1978); Igor Zabel and Moderna Galerija Ljubljana, Oho: Retrospektiva, 2nd ed. (Frankfurt am Main: Revolver, 2007). I am also deeply grateful to the former members of OHO—Marko Pogačnik, Iztok Geister, Naško Križnar, Tomaž Šalamun, Andraž Šalamun, Milenko Matanović, David Nez, Matjaž Hanžek, and Tomaž Brejc—who allowed me to interview them in 2009–10. My conversations with them were essential to my research.

1967: Book with a Ring

The need to contextualize OHO begins with the group’s name—a neologism derived from the Slovene words for “eye” (oko) and “ear” (uho)—which first appeared as the name of a self-published book by Marko Pogačnik and Iztok Geister in 1966.5 Only one object in the Information archive, Pogačnik’s Book with a Ring (1967), dates to the pre-1969 period.5The Museum of Modern Art Archive also lists this object with the alternative title “Book on a Ring.” Alternative views of the book are available from the Moderna Galerija, Ljubljana online collection and archive.One of a group of multiples produced, starting in 1966, as part of OHO Editions, it hints at the variety of formats with which OHO experimented during its short existence as a larger movement and later as an artist collective, which disbanded by early 1971.

In her essay for post, Klara Kemp-Welch notes: “Many of the proposals gathered in the exhibition Transmissions: Art in Eastern Europe and Latin America, 1960–1980 conquered new species of spaces for personal or collective investigation. So much so that artists’ propositions often fostered new forms of agency by repurposing and occupying new spaces.” Kemp-Welch turns, in particular, to observations about space made by the French writer Georges Perec, “for whom the space of the page is perhaps the creative space par excellence.” She cites Perec’s observation that “there are few events which don’t leave a written trace… At one time or another, almost everything passes through a sheet of paper… on which… one or another of the miscellaneous elements that comprise the everydayness of life comes to be inscribed.”6George Perec, “Species of Spaces,” in Species of Spaces and Other Pieces, trans. John Sturrock, Penguin classics (1974; trans., London: Penguin 2008), 12.

For OHO, these observations on the importance of pages are particularly relevant and go beyond the group’s heavy reliance on photographic documentation and subsequent use of diagrams. From its earliest days, as evidenced by OHO Editions, publishing in the broadest sense of the word was central to the group’s output, which up until 1968, largely consisted of idiosyncratic printed matter (including books, cards, and even labels that could be affixed to matchboxes) as well as journal and newspaper publications (including everything from drawings and comic strips to experimental poetry and theoretical texts).7The first publication that OHO founders Marko Pogačnik and Iztok Geister produced together was a 1963 journal called Plamenica (The Torch), which they created while still in high school. By 1965, when Pogačnik, Geister, and their friend and OHO’s main filmmaker, Naško Križnar came to Ljubljana to pursue university studies, the circle of their collaborators grew considerably larger as they became involved in several publications, eventually writing for and editing the university student newspaper, Tribuna (The Rostrum) and later the journal Problemi (Problems), which provided public forums in which the young radicals could put their ideas into wide circulation.

This interest in language and text was partly practical – the self-published OHO Editions did not require official support and were less likely to face official prohibitions. They also reached much wider audiences than unique art objects. The various pages on which OHO spread its ideas thus created a far bigger discursive space than the group would have been able to conjure had it begun as the smaller visual art collective that it would eventually become.8Looking at the Croatian Gorgona group, which was also represented in Transmissions, makes for a telling counterexample. While Gorgona was technically the earlier manifestation of neo-avant-garde activity in Yugoslavia, a strong argument can be made for OHO as the first publicly visible group whose activities had an impact on other artists in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s after the group disbanded as an artist collective. Made up of prominent Croatian artists who went for walks together, published an “anti-magazine,” and staged exhibitions, Gorgona was insular, focused exclusively on esoteric visual arts problems, and was known better to neo-avant-garde circles outside Yugoslavia than to fellow artists within the country; indeed, its rise to prominence owes more to scholarly discussions published long after its activities ended than to the impact of its activities when they first happened. As Ješa Denegri has written on post, “One of the paradoxes of Gorgona Group…is that it was almost completely unknown on the cultural scene in which it was embedded.” My comments are in no way meant to pass denigrating judgment on Gorgona in order to praise OHO, but to point out that in Eastern Europe, artists could and did choose from a range of possible responses to changing political circumstances, with some artists, like Gorgona, opting for what Denegri calls “a far-reaching strategy of silent contestation…on behalf of not only artistic but also total individual freedom,” while others, like OHO, especially in its earlier iterations, opted for publicly visible contestation and aiming to engage a broad public while also exploring the meaning of individual freedom.

Just as importantly, experiments with language allowed OHO members to introduce their audience to the philosophy of reism. Derived from the Latin res, meaning “thing,” reism’s philosophical task is to imagine new relationships between humans and everyday objects, between readers and text. In these anti-utilitarian relationships, objects would be liberated from having to be useful, and text from having to have meaning. As Marko Pogačnik has put it in an interview for ArtMargins Online, reism “demands that objects, and generally all entities, should be liberated of human appropriation in terms of purpose, function, sense, etc.” Though this line of working, like almost everything in OHO’s practice (except its constant propensity for experimentation), did not last long, it resulted in a group of striking works that includes Book with a Ring. Closely related to Marko Pogačnik’s earlier Item Book (1966), both objects embody OHO’s paradoxical relationship with language, with holes acting as basic units of a “text” that visualizes both the yearning for the complete (literal) transparency of language and the possibility that it is nothing but a string of (again literally) empty signifiers.9In 2016, the fiftieth anniversary of the creation of Item Book (the name can alternatively cited as Item: Book and also translated as Article Book) is being celebrated in Slovenia as the starting point of a tradition of artists’ books in that country. The press release for an exhibition dedicated to this tradition and with Marko Pogačnik’s account of the inspiration for the book can be found here. A copy of this book can be found in the MoMA Library Collection. In Book with a Ring, moreover, even the traditional codex structure of books, a utilitarian convention, is brought into question as the sequencing of the “pages” is left entirely to the viewer. Here, “language” obtains an obviously spatial dimension, which helps to shift the viewer’s expectations; the act of “reading” becomes focused not on the conveyance of content but rather on the open-minded and undirected encounter with the unfamiliar.

This is the first part of a multi-section essay on OHO Group that were released on post over a few weeks. It is complemented by images of newly digitized materials by OHO Group from the MoMA Archives as well as the first English translation of the 1969 interview between OHO Group members Milenko Matanović and Tomaž Šalamun.

- 1In reading the correspondence in the Information files, I was not able to establish the exact date of the meeting; McShine’s handwritten notes refer to Vidmar as “very nice student met in Nuremberg”; I surmise that Vidmar and McShine met some time in the summer, because the first letter in the correspondence that would result in OHO’s inclusion in the exhibition was dated by Tomaž Brejc, its author, August 15, 1969.

- 2Given her inclusion in Information, it is reasonable to surmise that Lucy Lippard first encountered OHO’s work at the show and later included the group in her important contribution to the early historiography of “dematerialized” art, Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972. The Czechoslovak artist Petr Štembera is the only other artist from Eastern Europe to make it into that book.

- 3Milenko Matanović, among others, has acknowledged the Brejcs’ important role for OHO in an interview with ArtMargins Online. “For those of us in Ljubljana, Tomaž and Taja Brejc became important friends and allies. We would often hang out at their home. They had international art magazines, which I would peruse. I am sure that some of those pictures influenced my artistic imagination. In addition, Tomaž, an art historian, was a keen observer of our activities and wrote about them. Opportunities for exhibits were undoubtedly opened up by his writings.”

- 4Though the conceptual framing of OHO’s intellectual history offered in this text is my own, my work owes a great debt to the research (including precise chronologies) and analysis offered in the histories of the group written by Slovene art historians Tomaž Brejc and Igor Zabel. For their most extensive texts, see Tomaž Brejc, Oho: 1966–1971 (Ljubljana: Študentski Kulturni Center, 1978); Igor Zabel and Moderna Galerija Ljubljana, Oho: Retrospektiva, 2nd ed. (Frankfurt am Main: Revolver, 2007). I am also deeply grateful to the former members of OHO—Marko Pogačnik, Iztok Geister, Naško Križnar, Tomaž Šalamun, Andraž Šalamun, Milenko Matanović, David Nez, Matjaž Hanžek, and Tomaž Brejc—who allowed me to interview them in 2009–10. My conversations with them were essential to my research.

- 5The Museum of Modern Art Archive also lists this object with the alternative title “Book on a Ring.” Alternative views of the book are available from the Moderna Galerija, Ljubljana online collection and archive.

- 6George Perec, “Species of Spaces,” in Species of Spaces and Other Pieces, trans. John Sturrock, Penguin classics (1974; trans., London: Penguin 2008), 12.

- 7The first publication that OHO founders Marko Pogačnik and Iztok Geister produced together was a 1963 journal called Plamenica (The Torch), which they created while still in high school. By 1965, when Pogačnik, Geister, and their friend and OHO’s main filmmaker, Naško Križnar came to Ljubljana to pursue university studies, the circle of their collaborators grew considerably larger as they became involved in several publications, eventually writing for and editing the university student newspaper, Tribuna (The Rostrum) and later the journal Problemi (Problems), which provided public forums in which the young radicals could put their ideas into wide circulation.

- 8Looking at the Croatian Gorgona group, which was also represented in Transmissions, makes for a telling counterexample. While Gorgona was technically the earlier manifestation of neo-avant-garde activity in Yugoslavia, a strong argument can be made for OHO as the first publicly visible group whose activities had an impact on other artists in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s after the group disbanded as an artist collective. Made up of prominent Croatian artists who went for walks together, published an “anti-magazine,” and staged exhibitions, Gorgona was insular, focused exclusively on esoteric visual arts problems, and was known better to neo-avant-garde circles outside Yugoslavia than to fellow artists within the country; indeed, its rise to prominence owes more to scholarly discussions published long after its activities ended than to the impact of its activities when they first happened. As Ješa Denegri has written on post, “One of the paradoxes of Gorgona Group…is that it was almost completely unknown on the cultural scene in which it was embedded.” My comments are in no way meant to pass denigrating judgment on Gorgona in order to praise OHO, but to point out that in Eastern Europe, artists could and did choose from a range of possible responses to changing political circumstances, with some artists, like Gorgona, opting for what Denegri calls “a far-reaching strategy of silent contestation…on behalf of not only artistic but also total individual freedom,” while others, like OHO, especially in its earlier iterations, opted for publicly visible contestation and aiming to engage a broad public while also exploring the meaning of individual freedom.

- 9In 2016, the fiftieth anniversary of the creation of Item Book (the name can alternatively cited as Item: Book and also translated as Article Book) is being celebrated in Slovenia as the starting point of a tradition of artists’ books in that country. The press release for an exhibition dedicated to this tradition and with Marko Pogačnik’s account of the inspiration for the book can be found here. A copy of this book can be found in the MoMA Library Collection.