In the second part of this multi-section essay, art historian Ksenya Gurshtein addresses OHO Group’s work in the year 1969. Consulting the MoMA Archives, she highlights and expands upon connections between the Slovene conceptual artists OHO Group and one of the Museum’s most well-known exhibitions, Information of 1970. Archival materials from Information were on display in the fall 2015 exhibition Transmissions: Art in Eastern Europe and Latin America, 1960–1980.

1969: Summer Projects

1968 brought changes to the OHO circle. With Pogačnik gone for a year of obligatory military service, other members shifted their attention to performances in urban spaces, notably Ljubljana’s centrally located Zvezda Park. It was there, at the end of December, that three members performed Triglav, one of the group’s most iconic works—a witty visual pun on the name of Slovenia’s tallest peak, which means “three-headed.” Against the background of the snowy park, Milenko Matanović, David Nez, and Drago Dellabernardina stuck their heads through a black tarp and became the three-headed mountain, eliciting quizzical and bemused responses from passersby.

Though the “social dimension” of this and similar works that Matanović invoked in a 1969 interview (recently translated into English for post), was not explicitly spelled out, it was certainly related to the idea that artists should claim public space as their own, as an important way of contesting official power. This sentiment, which resonated around the globe, was also captured by McShine in his introduction to the Information catalog: “The material presented by the artists is considerably varied, and also spirited, if not rebellious —which is not very surprising, considering the general social, political, and economic crises that are almost universal phenomena of 1970. . . . It may seem too inappropriate, if not absurd, to get up in the morning, walk into a room, and apply dabs of paint from a little tube to a square of canvas. What can you as a young artist do that seems relevant and meaningful?”1Kynaston McShine, ed., Information, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1970), 138.

For OHO, in the summer of 1969, following the group’s transformation into a more tightly-knit collective and forays into exhibition-making, the answer to McShine’s question lay in continuing to explore ways of working outside of traditional gallery spaces.2It’s important to note that OHO did continue to exhibit until 1971 when opportunities to do so presented themselves, thus constantly moving between institutional art spaces and the spaces of nature or everyday life. In addition to the catalog of the 1969 Zagreb exhibition, the MoMA Archives contain another catalog, a miniature publication from November 1969 that reproduces the photo-documentation of OHO’s installations and performances in nature between March and November of that year. The catalog was published on the occasion of the group’s exhibition at the Tribuna Mladih in Novi Sad, Serbia and points to the group’s continued interest even after its move outside the gallery in ensuring that a record of its work existed and was available for exhibition display, as in the case of Information, where curatorial files indicate that photographs of some of OHO’s works were blown up to a size as great as four by six feet. The series of Summer Projects that were the result of these efforts and are so richly documented in the MoMA Archives are a testament to this period of intensive experimentation. With Pogačnik’s return that spring, the collective was re-formed into its most stable configuration—four members that included Pogačnik, Nez, Matanović, and Andraž Šalamun.3David Nez: “If memory serves me right Marko was serving in the army around the time I started with OHO. I was familiar with his work and found it interesting but was more directly influenced by the work of Milenko and Andraž in the beginning as we collaborated a lot at that time on ‘actions’ and ‘happenings’ at Zvezda Park as well as making ‘objects.’ If I remember correctly, Milenko, Andraž and Tomaž, and I worked together while Marko was gone, culminating in the Pradjedovi exhibit in Zagreb. Marko joined us again during the exhibit at Moderna Galerija and in the following shows, and our group constellation changed again when he returned.” See Beti Žerovc, “The OHO Files”: Interview with David Nez.” Art Margins Online (24 August 2011).

Together, they began to work extensively, first in natural spaces within Ljubljana and then progressively further into the countryside. According to Pogačnik, this decision, much like the group’s other key choices, was shaped partly by its members’ aesthetic interests and partly by political exigencies. Though cultural production in Yugoslavia was not as restricted as it was in Warsaw Pact countries, artists were constantly aware of potential repercussions and the whims of the authorities. Further, in culturally conservative Slovenia, with Tomaž Šalamun’s departure from his curatorial post at Moderna Galerija, no venue would exhibit OHO, making the move into nature logistically sensible.4Indeed, starting in 1969, almost all of OHO’s important exhibitions happened either in other Yugoslav cities or abroad. Marko Pogačnik: “After the Atelje 69 exhibition at the Moderna Galerija (Ljubljana) there was a crisis. We wanted to go on developing our ideas, but had no way of showing our work. I suggested that we exchange the museum or gallery spaces for natural settings. Thus our series of land artworks came about. We made works throughout that summer, and that really formed the group as such.” See Beti Žerovc, “The OHO Files”: Interview with Marko Pogačnik.” Art Margins Online (24 August 2011). Although the political climate in Slovenia was relatively liberal in terms of repercussions faced by artists who pursued unconventional artistic paths, events such as the closure of Tomaž Šalamun’s exhibition in 1969, when his ill-fated one-man show in the small town of Kranj was closed by the authorities after one day, point to the artists’ constant need to adjust to the surrounding political situation. OHO’s choice to move to working in nature can be productively compared to those made by artists elsewhere in Eastern Europe: “One of the most respected Czech artists in recent times, Jiří Kovanda created actions and installations in Prague’s public spaces in the mid-1970s and early ’80s. Self-taught, he was one of the few Czech action artists to work outdoors in the urban environment following the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact troops. Most of the country’s progressive artists had gone underground, to the privacy of ateliers and small groups of friends, or created art in rural settings, out of the sight of the watchful eyes of state security, their agents and informants. Czech culture languished at that time due to its inability to communicate with most of its audience, since galleries and the art market, too, were under strict surveillance. Jiří Kovanda was one of few artists who managed “not to notice”, as it were, this unfavorable situation.” See Pavlina Morganova, “A Walk Through Prague with Jiří Kovanda.” post (May 19, 2015).

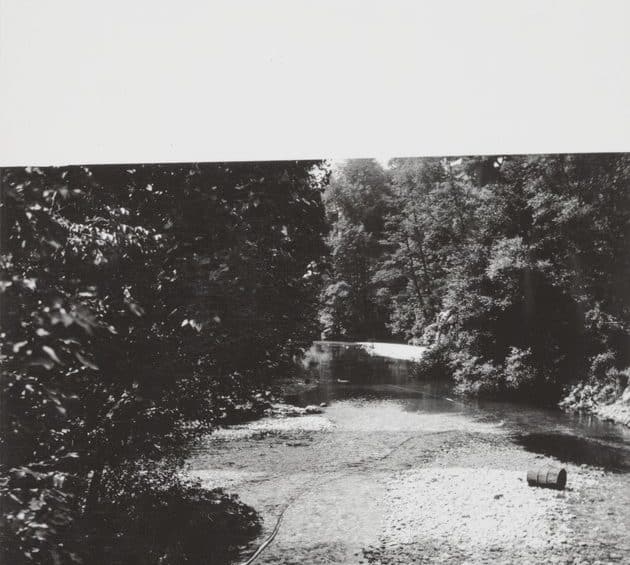

Within Ljubljana, the group explored the creative possibilities of everyday public space, as in Matanović’s Snake, a work in which the artist tied together sticks with string and then lowered them into the Ljubljanica river running beneath his window to reveal an otherwise invisible current.5Milenko Matanović: “I lived at Wolfova 1 and we had access to the balcony overlooking the Ljubljanica river. I always liked looking for fish from the balcony, and while doing so I noticed the almost invisible currents that moved through the channeled water. I started to think about how to make those currents more visible and came up with a ‘snake’ of wooden pieces connected by a rope. I was delighted to see the snake form replicate the slow, beautiful, meditative and meandering movements of the river. I did a sister piece that similarly highlighted the rolling landscape around Medvode. I bought a role [sic] of paper, some 200m long, and simply rolled it out. Influenced by gravity, the paper meandered through the meadow in a most beautiful way. But I haven’t seen any pictures of that piece. . . . I especially liked how I was able to make visible the invisible currents in the Ljubljanica river.” See Beti Žerovc, “The OHO Files”: Interview with Milenko Matanović.” Art Margins Online (24 August 2011). The MoMA Archives has images of the paper piece that, as Matanović notes, have not survived in any other archive. In a companion piece, Paper Path,6In an e-mail to the author, Matanović wrote, “All installations were temporary. I did not give them titles but will make them up now.” E-mail from Milenko Matanović to the author, May 30, 2016. he used a very large roll of blank newsprint to highlight the gentle rolling of a hilly landscape just outside the city. (Here, too, it is worth noting, that the choice of materials was dictated by practical concerns as much as aesthetic preferences—the artists were buying their own supplies and working with tiny budgets, and they thus opted for inexpensive materials).7Ibid. If in Snake and Paper Path, Matanović drew attention to easy-to-miss natural phenomena, in other works, he ever so gently and temporarily altered the landscape. Using rolls of the same type of blank newsprint, he made Waves in Zvezda Park by tying two strings to trees and draping the paper over them;8Ibid. in one of his most iconic works, Wheat and Rope, he used a piece of rope, which was tied to a stick stuck in the ground, to bend stalks of wheat into a temporary line in the field.9Milenko Matanović: “The summer of 1969 was a wonderful time for me. I found very inexpensive materials—string, wood, paper—to highlight what I noticed in nature. I placed a stick in the ground on one end of a wheat field, attached a rope to it, and then tried to attach it to another stick at the other end. The resulting tension uprooted the stick, so I settled for bending it by hand. I wanted to create many more projects with this method with many lines on a field, but I never got around to it. Perhaps I will one of these days.” See Beti Žerovc, “The OHO Files”: Interview with Milenko Matanović.” Art Margins Online (24 August 2011).

In her recent book The Green Bloc: Neo-Avant-Garde Art and Ecology under Socialism, Maja Fowkes persuasively links OHO’s Summer Projects and subsequent works with the rise of an environmentalist consciousness in the late 1960s’ counterculture.10Marko Pogačnik: “We were always interested in whatever was forbidden and rejected by the ruling system of thought (politics). At that time, spirituality and ecology were off limits.” See Beti Žerovc, “The OHO Files”: Interview with Marko Pogačnik.” Art Margins Online (24 August 2011). In a work as seemingly simple as Wheat and Rope, Fowkes sees an exploration of an attitude toward nature that, inspired by the philosophy of Martin Heidegger, embeds man non-disruptively in his environment, presenting an alternative to an alienated and technophilic stance towards nature as a limitless resource to be exploited.11Maja Fowkes, The Green Bloc: Neo-Avant-Garde Art and Ecology Under Socialism (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2015), 86–87.

Fowkes’s larger argument is borne out by OHO members’ biographies following the dissolution of the group: both Matanović and Nez spent time at the eco-conscious Findhorn community in Scotland while Pogačnik, until 1979, ran the commune that he and fellow OHO members founded in the Slovene village of Šempas.

Overlapping the environmentalist concerns of OHO’s works, however, is their existence within the constellation of late-1960s aesthetic practices. To try to assign a precise definition or term for these and other OHO works is to miss the point that individual pieces were part of ongoing experimentation, the process of which was more important than the end results. OHO’s practice, like many discussed on post and represented in Transmissions, was a living answer to Klara Kemp-Welch’s question in her essay published on post: “What happens when pedagogy, poetry, sculpture, and sociability bleed into one another, and categories such as Conceptual art, Happenings, or performance art are undone?” McShine, too, seems to have been aware of the futility of assigning labels and identifying influences when he curated Information. As he wrote in the catalog that accompanied the exhibition, “An intellectual climate that embraces Marcel Duchamp, Ad Reinhardt, Buckminster Fuller, Marshall McLuhan, the I Ching, the Beatles, Claude Lévi-Strauss, John Cage, Yves Klein, Herbert Marcuse, Ludwig Wittgenstein and theories of information and leisure inevitably adds to the already complex situation.”12Kynaston McShine, ed., Information, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1970), 139–40. Several of the influences McShine mentions were directly relevant to OHO: the group’s early reist work, for example, playfully responded to Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus in its resistance to linguistic abstraction, while many later works, particularly those that celebrated countercultural, antiestablishment attitudes, followed in the spirit of Herbert Marcuse’s 1969 New Left manifesto, An Essay on Liberation, with OHO films often featuring Rolling Stones soundtracks as a manifestation of the group’s affinity with the counterculture.

Nevertheless, the term transcendental conceptualism, which Tomaž Brejc created to characterize OHO’s late work, is insightful—both in terms of understanding the group’s interests and expanding the definition of Conceptualism as it applies to a variety of artistic practices around the world.13Tomaž Brejc, Oho: 1966–1971 (Ljubljana: Študentski Kulturni Center, 1978), 30. Brejc applied the term “transcendental conceptualism” more narrowly to work done in 1970 and 1971, but in my use of his term, I find it applicable to some of the group’s earlier works, particularly the Summer Projects. Here, rereading McShine is again helpful, for he too seems to have chafed at the definition of Conceptualism as it was understood by its New York exponents, particularly Joseph Kosuth: “The art cannot afford to be provincial, or to exist only within its own history, or to continue to be, perhaps, only a commentary on art. An alternative has been to extend the idea of art, to renew the definition, and to think beyond the traditional categories—painting, sculpture, drawing, printmaking, photography, film, theater, music, dance, and poetry.”14McShine, Information, 138; Hinting again at what a big tent Conceptualism was for McShine, in a letter to Marcel Duchamp’s widow found in the Information files, McShine wrote, “Most of the artists seem to be ‘grandsons’ of Marcel, and I think of the exhibition almost as a ‘homage’ to him.”

The impulse to work across and outside traditional media was certainly true of OHO, but even more importantly, the group operated within what we might now understand as a broader definition of a global Conceptualism whose main principle was to make invisible forces – be they natural, social, cosmological, interpersonal, or internal to the art world – visible.

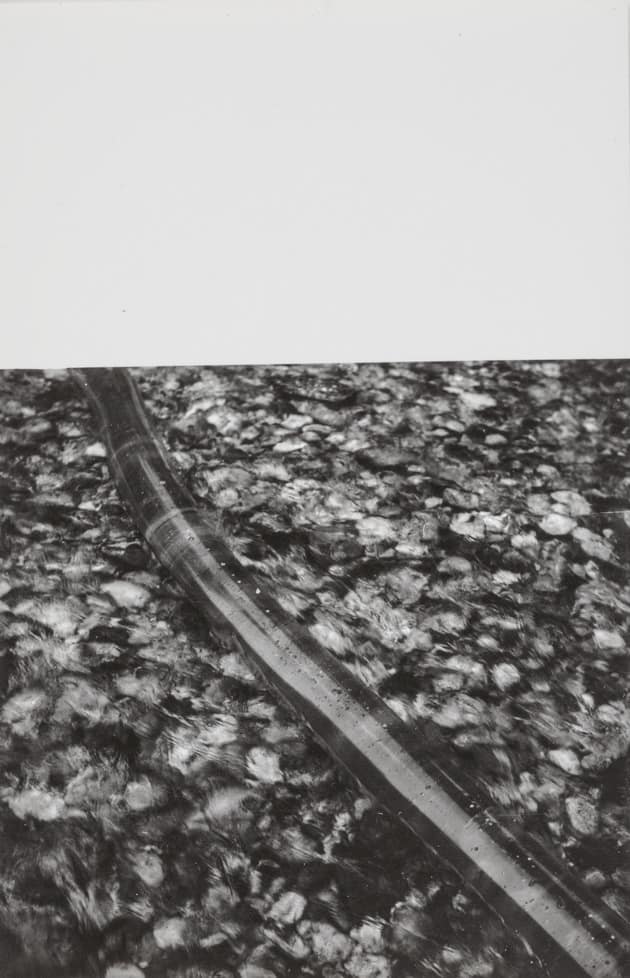

In some cases, such as in Matanović’s Snake and Paper Path, natural forces were made visible through the work. In others, such as in Pogačnik’s Family of fire, air and water, the work exposed both natural forces and human ways of structuring the understanding of such forces. Taking as his starting point the elements that the ancient Greeks described as the basic building blocks of the world (earth, air, fire, and water), Pogačnik created a series of works that showed relationships between the elements in both static and dynamic modes. Illustrated here is Water-Water Dynamic, in which a clear plastic tube filled with pigment was placed in a riverbed facing upstream, causing the pigment to expose the rapidity and direction of the current as it dissolved and moved in the opposite direction.15Marko Pogačnik: “I have always been fascinated by the reactions between the four elements. This is a series of projects that involve two of the given elements each, in different combinations. The number of combinations is further increased with the relationship between the elements being passive and active. Thus, for instance, there are the projects Water—Air, Static that I carried out on the Sava River near Kranj, as well as Water—Air, Dynamic, which was carried out on the island of Srakane in the Adriatic Sea.” See Beti Žerovc, “The OHO Files”: Interview with Marko Pogačnik.” Art Margins Online (24 August 2011). See also Fowkes, The Green Bloc, 82. Recorded on film, the footage is accompanied by a diagram (that quintessentially Conceptualist mode of expression), also included in the film, that schematizes the setup of the experiment.16Though not discussed here, filmmaking was an important activity for OHO and films constitute a significant part of the group’s creative output. Stills from OHO films can be found on-line on the site of the Marinko Sudac Collection here and here. During Information, OHO was represented not only by photographs, but also by a forty-five minute film that documented the group’s work in nature and was shot by Naško Križnar. At the same time, the use of a premodern system of knowledge as a starting point further highlights the tension between the sight of the entropic natural phenomenon and the human imposition of order onto it. In the end, Pogačnik’s work makes both more visible.

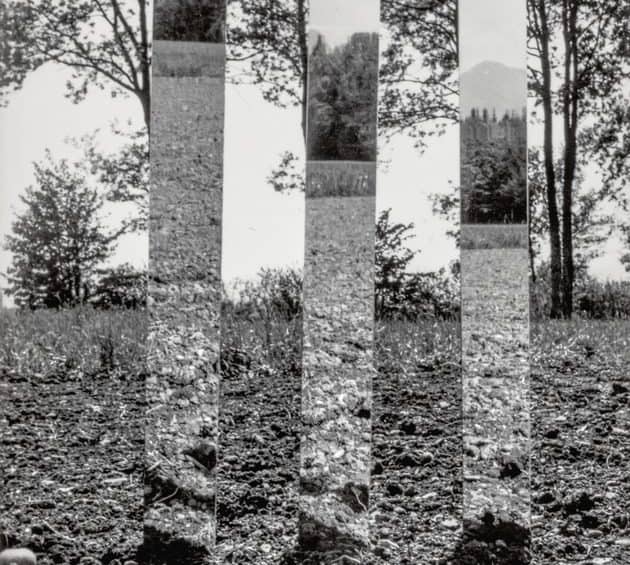

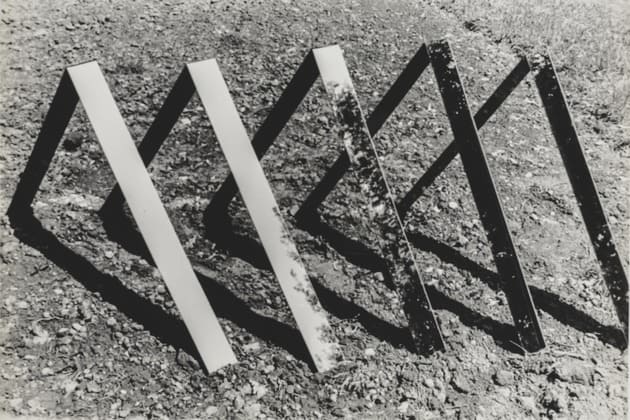

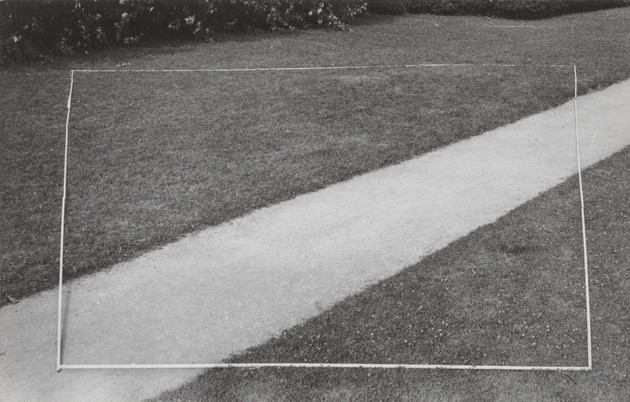

Nez, an American student studying art in Ljubljana, who became a member of OHO in 1968, similarly turned to issues of the visible and the invisible in his Summer Projects works. In pieces inspired by the work of Robert Smithson, such as Yucatan Mirror Displacements (1-9) from 1969, Nez exposed the limits of the photographic process, using mirrors placed in different configurations within the landscape to reflect that which would otherwise have been outside the shot.17David Nez: “I was inspired partly by Robert Smithson’s use of mirrors but was interested in exploring landscape photography in a new way by integrating modular sculpture with reflection of the environment.” See Beti Žerovc, “The OHO Files”: Interview with David Nez.” Art Margins Online (24 August 2011). The mirrors also break up the landscape they depict, reminding the viewer of the inescapable fact that every photograph is a more or less random fragment of reality. In another work untitled work, Nez pursued an exercise in perspective distortion. He explained: “I laid out a large trapezoid using wooden sticks on a field and photographed the shape from a specific viewpoint creating the illusion of a rectangle. This is reinforced by its alignment to the rectangular format of the camera viewfinder and resulting photographic print. The piece was intended as a sort of conceptual joke exploring the ambiguity of perspective and the tendency of the camera to flatten out three-dimensional space to a two-dimensional picture plane.”18E-mail from David Nez to the author, July 10, 2016; in recent years, Nez has returned to creating temporary string installations in outdoor spaces.

This is the second part of a multi-section essay on OHO Group. Read Part 1 here. It is complemented by images of newly digitized materials by OHO Group from the MoMA Archives as well as the first English translation of the 1969 interview between OHO Group members Milenko Matanović and Tomaž Šalamun. Read the interview here.

Marko Pogačnik: “When I came back from doing compulsory military service in the spring of 1969, the situation with OHO was fairly critical. The early stage, the OHO Movement, had drawn to a close; the initial enthusiasm and drive were gone. On the other hand, there was the excellent exhibition Great-Grandfathers, which David Nez, Milenko Matanović, and Andraž and Tomaž Šalamun had staged in Zagreb, shifting in this way the focus of artistic creativity to visual art, partly inspired by the avant-garde art of the time, such as Arte Povera. There was even the idea that such activities should be separated from OHO. I was opposed to this; I believed that the philosophy underpinning OHO was too good to be replaced by art tendencies of the moment. In the end, it was David Nez who arrived at the decision with characteristic American pragmatism: that we should be the OHO Group, since OHO already existed as a familiar term. In its final form the group, comprised of David Nez, Milenko Matanović, Andraž Šalamun, and myself, took shape in the summer of 1969.” See Beti Žerovc, “The OHO Files”: Interview with Marko Pogačnik.” Art Margins Online (24 August 2011).

Milenko Matanović: “Initially we created informal opportunities for sharing our individual work. My recollection is that the group didn’t come together until the first exhibit—I think at the Gallery of Modern Art in Ljubljana—and we had to get organized. I do not recall who made the selections of artists. Marko was the front man and I think that he negotiated the exhibit. I simply recall that I was invited and that we very quickly received invitations to exhibits in Maribor and Zagreb and the group became more formed with each invitation. The core group was Marko, Andraž, and myself, and later David. Tomaž Šalamun drifted in and out of visual art. Poetry was his main expression and he got involved on several occasions, but not on an ongoing basis. I think his art was a visual extension of his poetry, while for the rest of us it quickly became the main focus.” See Beti Žerovc, “The OHO Files”: Interview with Milenko Matanović.” Art Margins Online (24 August 2011).

- 1Kynaston McShine, ed., Information, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1970), 138.

- 2It’s important to note that OHO did continue to exhibit until 1971 when opportunities to do so presented themselves, thus constantly moving between institutional art spaces and the spaces of nature or everyday life. In addition to the catalog of the 1969 Zagreb exhibition, the MoMA Archives contain another catalog, a miniature publication from November 1969 that reproduces the photo-documentation of OHO’s installations and performances in nature between March and November of that year. The catalog was published on the occasion of the group’s exhibition at the Tribuna Mladih in Novi Sad, Serbia and points to the group’s continued interest even after its move outside the gallery in ensuring that a record of its work existed and was available for exhibition display, as in the case of Information, where curatorial files indicate that photographs of some of OHO’s works were blown up to a size as great as four by six feet.

- 3David Nez: “If memory serves me right Marko was serving in the army around the time I started with OHO. I was familiar with his work and found it interesting but was more directly influenced by the work of Milenko and Andraž in the beginning as we collaborated a lot at that time on ‘actions’ and ‘happenings’ at Zvezda Park as well as making ‘objects.’ If I remember correctly, Milenko, Andraž and Tomaž, and I worked together while Marko was gone, culminating in the Pradjedovi exhibit in Zagreb. Marko joined us again during the exhibit at Moderna Galerija and in the following shows, and our group constellation changed again when he returned.” See Beti Žerovc, “The OHO Files”: Interview with David Nez.” Art Margins Online (24 August 2011).

- 4Indeed, starting in 1969, almost all of OHO’s important exhibitions happened either in other Yugoslav cities or abroad. Marko Pogačnik: “After the Atelje 69 exhibition at the Moderna Galerija (Ljubljana) there was a crisis. We wanted to go on developing our ideas, but had no way of showing our work. I suggested that we exchange the museum or gallery spaces for natural settings. Thus our series of land artworks came about. We made works throughout that summer, and that really formed the group as such.” See Beti Žerovc, “The OHO Files”: Interview with Marko Pogačnik.” Art Margins Online (24 August 2011). Although the political climate in Slovenia was relatively liberal in terms of repercussions faced by artists who pursued unconventional artistic paths, events such as the closure of Tomaž Šalamun’s exhibition in 1969, when his ill-fated one-man show in the small town of Kranj was closed by the authorities after one day, point to the artists’ constant need to adjust to the surrounding political situation. OHO’s choice to move to working in nature can be productively compared to those made by artists elsewhere in Eastern Europe: “One of the most respected Czech artists in recent times, Jiří Kovanda created actions and installations in Prague’s public spaces in the mid-1970s and early ’80s. Self-taught, he was one of the few Czech action artists to work outdoors in the urban environment following the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact troops. Most of the country’s progressive artists had gone underground, to the privacy of ateliers and small groups of friends, or created art in rural settings, out of the sight of the watchful eyes of state security, their agents and informants. Czech culture languished at that time due to its inability to communicate with most of its audience, since galleries and the art market, too, were under strict surveillance. Jiří Kovanda was one of few artists who managed “not to notice”, as it were, this unfavorable situation.” See Pavlina Morganova, “A Walk Through Prague with Jiří Kovanda.” post (May 19, 2015).

- 5Milenko Matanović: “I lived at Wolfova 1 and we had access to the balcony overlooking the Ljubljanica river. I always liked looking for fish from the balcony, and while doing so I noticed the almost invisible currents that moved through the channeled water. I started to think about how to make those currents more visible and came up with a ‘snake’ of wooden pieces connected by a rope. I was delighted to see the snake form replicate the slow, beautiful, meditative and meandering movements of the river. I did a sister piece that similarly highlighted the rolling landscape around Medvode. I bought a role [sic] of paper, some 200m long, and simply rolled it out. Influenced by gravity, the paper meandered through the meadow in a most beautiful way. But I haven’t seen any pictures of that piece. . . . I especially liked how I was able to make visible the invisible currents in the Ljubljanica river.” See Beti Žerovc, “The OHO Files”: Interview with Milenko Matanović.” Art Margins Online (24 August 2011). The MoMA Archives has images of the paper piece that, as Matanović notes, have not survived in any other archive.

- 6In an e-mail to the author, Matanović wrote, “All installations were temporary. I did not give them titles but will make them up now.” E-mail from Milenko Matanović to the author, May 30, 2016.

- 7Ibid.

- 8Ibid.

- 9Milenko Matanović: “The summer of 1969 was a wonderful time for me. I found very inexpensive materials—string, wood, paper—to highlight what I noticed in nature. I placed a stick in the ground on one end of a wheat field, attached a rope to it, and then tried to attach it to another stick at the other end. The resulting tension uprooted the stick, so I settled for bending it by hand. I wanted to create many more projects with this method with many lines on a field, but I never got around to it. Perhaps I will one of these days.” See Beti Žerovc, “The OHO Files”: Interview with Milenko Matanović.” Art Margins Online (24 August 2011).

- 10Marko Pogačnik: “We were always interested in whatever was forbidden and rejected by the ruling system of thought (politics). At that time, spirituality and ecology were off limits.” See Beti Žerovc, “The OHO Files”: Interview with Marko Pogačnik.” Art Margins Online (24 August 2011).

- 11Maja Fowkes, The Green Bloc: Neo-Avant-Garde Art and Ecology Under Socialism (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2015), 86–87.

- 12Kynaston McShine, ed., Information, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1970), 139–40.

- 13Tomaž Brejc, Oho: 1966–1971 (Ljubljana: Študentski Kulturni Center, 1978), 30. Brejc applied the term “transcendental conceptualism” more narrowly to work done in 1970 and 1971, but in my use of his term, I find it applicable to some of the group’s earlier works, particularly the Summer Projects.

- 14McShine, Information, 138; Hinting again at what a big tent Conceptualism was for McShine, in a letter to Marcel Duchamp’s widow found in the Information files, McShine wrote, “Most of the artists seem to be ‘grandsons’ of Marcel, and I think of the exhibition almost as a ‘homage’ to him.”

- 15Marko Pogačnik: “I have always been fascinated by the reactions between the four elements. This is a series of projects that involve two of the given elements each, in different combinations. The number of combinations is further increased with the relationship between the elements being passive and active. Thus, for instance, there are the projects Water—Air, Static that I carried out on the Sava River near Kranj, as well as Water—Air, Dynamic, which was carried out on the island of Srakane in the Adriatic Sea.” See Beti Žerovc, “The OHO Files”: Interview with Marko Pogačnik.” Art Margins Online (24 August 2011). See also Fowkes, The Green Bloc, 82.

- 16Though not discussed here, filmmaking was an important activity for OHO and films constitute a significant part of the group’s creative output. Stills from OHO films can be found on-line on the site of the Marinko Sudac Collection here and here. During Information, OHO was represented not only by photographs, but also by a forty-five minute film that documented the group’s work in nature and was shot by Naško Križnar.

- 17David Nez: “I was inspired partly by Robert Smithson’s use of mirrors but was interested in exploring landscape photography in a new way by integrating modular sculpture with reflection of the environment.” See Beti Žerovc, “The OHO Files”: Interview with David Nez.” Art Margins Online (24 August 2011).

- 18E-mail from David Nez to the author, July 10, 2016; in recent years, Nez has returned to creating temporary string installations in outdoor spaces.