Selections by Uesaki Sen and Miki Kaneda; Annotations by Miki Kaneda

Graphic scores visibly and sonically changed contemporary music in the late 1950s and ’60s. The new notation unleashed a torrent of fundamental questions about music, sound, and composition: What counts as music? What distinguishes musical sound from non-musical sound? What is the time of music, and can there be alternatives to industrial clock-time? What assumptions about performance and skill underlie formal musical training? As Akiyama Kuniharu and Ichiyangi Toshi brought their knowledge of music and graphics from their experiences in Germany and the United States to Japan between 1959 and 1961, excitement surrounding graphic notation and its aesthetic possibilities spread rapidly among experimental composers, critics, and composers working around Tokyo. This annotated bibliography presents a selection of essays and articles about the new notational forms. Some, like Donald Richie, wrote scathing criticisms of the scores and performances linked to the aesthetics of chance and indeterminacy. Others, like Takahashi Yuji, questioned the motivation for using graphic notation: is it employed merely as a utilitarian tool for making writing easier, or is it viewed as the basis of a new aesthetic?

Two exhibitions presenting graphic scores in Tokyo in 1962 and the surrounding discourse attest to the high level of interest generated by the new form not only among musicians, but also among artists and designers. In about 1962 the critic Akiyama began using the term “graphic scores” to refer to the scores that used graphic notation. This reflects a profound change in the concept of the score itself, first as a combination of musical practice and graphic design using new forms of notation, and then as a hybrid object that stands on its own, potentially even independently of music and performance.

After the early 1960s, many of the pioneers of graphic scores returned to traditional notation, while others stopped writing scores in favor of instructions or embraced free improvisation. It’s difficult to say why the popularity of the form was so short-lived. One way to approach the question is to return to the conversations that took place in the early 1960s. Another is to turn to composers and performers working today and ask about their relationship to scores and notation. How might scores operate with a new, contemporary significance in tandem with the abundance of recorded sound available online today?

Source contents

Of Theory, the Aleatoric, and Space

by Nam June Paik, December 1959

Paik discusses recent developments in music theory and composition, notably the use of chance operations and indeterminacy in the music of John Cage, Morton Feldman, and Christian Wolff. The essay is by a young Paik, still deeply immersed in the study of contemporary Western classical music and the debates that surround it. Includes excerpts of graphic scores by Cage, Feldman, and Earle Brown.

Publication: 「セリー・偶然・空間など」 Ongaku Geijutsu 17(13), 82−101

Language: Japanese

Notation and Graphism: New Tendencies in Modern European Music

by Akiyama Kuniharu, March 15, 1960

Akiyama writes about his encounter with graphic notation during his European travels from August to October 1959. He is particularly impressed by the idea of notation and musical graphics as representations of “moving forms” in Stockhausen’s music. He reports that the European experiments with graphic notation are tied to efforts to conceptualize “new senses of time and space.”

Publication: 「記譜とグラフィズムーーヨーロッパ現代音楽の新傾向」 The Yomiuri Shimbun

Language: Japanese

New Directions in Sound and Image (Round Table) 1

by Akiyama Kuniharu, May 1960

In conversation with the artist Yamaguchi Katsuhiro, musician and critic Akiyama Kuniharu discusses his recent trip to Paris and Germany, commenting on the state of contemporary music (particularly musique concrète and electronic music) and the music festival circuits in Germany. Yamaguchi draws Akiyama out on the subject of Moving Forms, a new approach to composition that he encountered at the Domaine Musical concerts in Paris. Akiyama explains that among the composers featured in Domaine Musical, the aim of music composition is shifting from forming melodies and harmony by arranging a succession of pitches to creating acoustic space and time through movement. In the second half of the interview, Akiyama speaks with great excitement about his encounter with the new graphic notation used by composers such as Karlheinz Stockhausen, Luciano Berio, and Sylvano Bussotti, among others. Contains images of graphic scores by Stockhausen, Berio, and Bussotti.

Publication: 「音と形のあたらしい展望(対談)-1-」 Bijutsu Techo 173, 69–79

Language: Japanese

New Directions in Sound and Image (Round Table) 2

by Akiyama Kuniharu, June 1960

Part two of the conversation between Akiyama and Yamaguchi takes up the topic of new entanglements of sound and image, with a focus on jazz and action painting. Yamaguchi opens the conversation with the statement “I think abstract art and electronic music are related in the sense that they are both deeply invested in rationalism.” This is followed by a discussion of the relationship of rationalism, anti-rationalism, indeterminacy, and improvisation in music and painting. Akiyama notes a concentration of new and exciting electronic music coming out of Poland: “I am fascinated by the search for a new musical language in Poland in the midst of building a new social state, and a new society.” Contains images of graphic scores and notation by Stockhausen, Boulez, and Cage.

Publication: 「音と形のあたらしい展望(対談)-2-」 Bijutsu Techo 174, 62−75

Language: Japanese

Toward a New Approach to Time and Space 1

by Akiyama Kuniharu, March 1960

Part one of a report following Akiyama’s trip to Europe and his encounter with the idea of Music and Graphics (Musik und Graphik) during a five-part talk on the subject by Karlheinz Stockhausen.

Publication: 「音楽の新しい時間と空間への試み I 」 SAC, no. 1, n.p.

Language: Japanese

Toward a New Approach to Time and Space 2

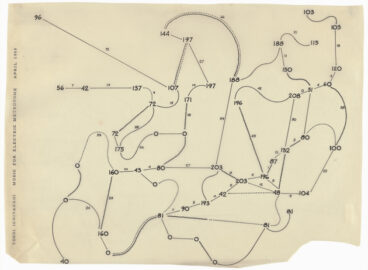

by Akiyama Kuniharu, April 1960

Part two of a report following Akiyama’s trip to Europe. Akiyama writes about Musikalische Graphik, an exhibition of graphic scores held at the Donaueschingen Music Festival, along with performances of graphic score pieces by Roman Haubenstock-Ramati and Sylvano Bussotti, conducted by Pierre Boulez. These new notational forms, he argues, are attempts by young avant-garde artists to create a new sense of time and space through the intersection of music and graphics. Illustrations include photographs of a rehearsal in Cologne and an excerpt of Bussotti’s score.

Publication: 「音楽の新しい時間と空間への試み II」 SAC, no. 2, n.p.

Language: Japanese

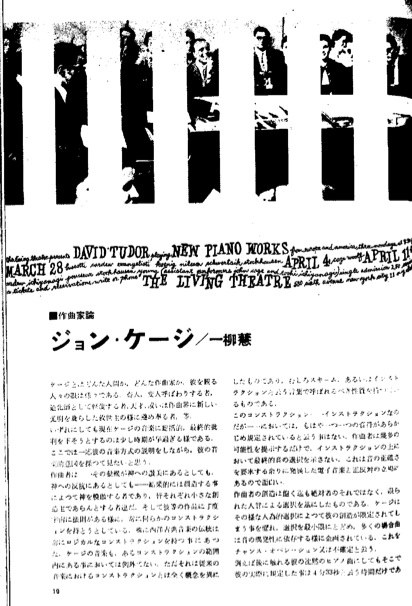

John Cage

by Ichiyanagi Toshi, February 1961

An introduction to the music and thought of John Cage, focusing on his work since the late 1950s and exploring concepts such as indeterminacy, chance, natural sounds, and the musical approach to silence. Also includes a discussion of graphic notation and instruction-based scores.

Publication: 「ジョン・ケージ」 The Ongaku-Geijutsu 19(2) , 10−16

Language: Japanese

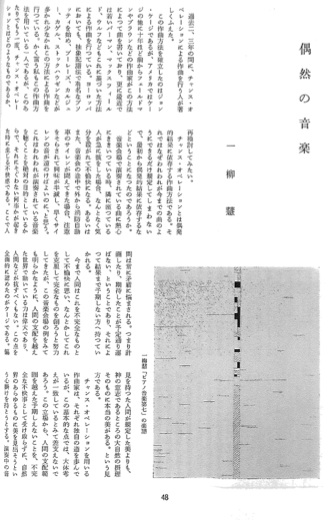

Music of Chance

by Ichiyanagi Toshi, October 1961, 48−50

Ichiyanagi introduces readers to chance operations in his own music and in the music of others, including Morton Feldman, Richard Maxfield, and Sylvano Bussotti. He credits John Cage with establishing chance operations as a compositional method. Cage’s method is groundbreaking, he writes, because the music of chance begins with the premise that “beauty happens in all sounds that occur in the environment.” Illustrations include images of scores by Cage and Ichiyanagi.

Publication: 「偶然の音楽」 Geijutsu Shincho 12(10)

Language: Japanese

Design (A Proposal for New Scores)—From This Year’s JAAC Exhibition

by Akiyama Kuniharu, October 25, 1961

Akiyama writes about an experiment undertaken at the Nissenbi (Japan Advertising Artists Club) exhibition of 1961, where designers rather than composers presented visual proposals for making musical notation suitable for contemporary musical sensibilities.

Publication: 「デザイン〈新しい楽譜のための提案〉——ことしの日宣美展から」 SAC Journal, no. 19, n.p.

Language: Japanese

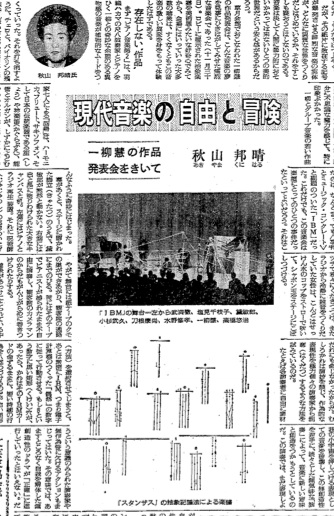

Design (A Proposal for New Scores)—From This Year’s JAAC Exhibition

by Akiyama Kuniharu, December 8, 1961

In his review of Ichiyanagi’s concert at the Sogetsu Art Center on November 30, 1961, Akiyama writes for the general public about the new graphic notation. “There is the sense that music is an aestheticized form that is incapable of violently attacking people.” With this statement, he implies that the new music might possess the capacity for violence. Another idea to ponder: “The ‘work’ does not exist a priori [before performance].” Includes an image of Ichiyanagi’s graphic score for “Stanzas” and a description of his piece “IBM.”

Publication: 「現代音楽の自由と冒険 一柳慧の作品発表会をきいて」 Yomiuri Shimbun, Evening edition, 7

Language: Japanese

Nature and Music

by Ichiyanagi Toshi, February 1962

Part one of a three-part series. Writing about the ecology of everyday sounds in the city, Ichiyanagi opens with Cage’s questions: “Is music just sound?” and “Is the sound of a truck passing also music?” Arguing that traditional notation (using a five-line staff and notes) privileges the authority of the composer while de-emphasizing the natural environment, the essay follows the trajectory of European and American composers such as Varèse and Cage, who “reintroduced” into music the material and acoustic reality of sound.

Publication: 「自然と音楽」 Ongaku-Geijutsu 20(2), 6−9

Language: Japanese

The Meaning of Changing Signs: Looking at Graphic Scores

by Takiguchi Shuzo, March 1962

Beginning with descriptions of graphic scores realized as collaborations between composers and designers (Takahashi Yuji and Wada Makoto; Takemitsu Toru and Sugiura Kohei), and of a then-rare example of musical performance in an art gallery (Group Ongaku at an exhibition of paintings by Hiraoka Hiroko), Akiyama proceeds with a discussion of new undertakings by composers, performers, and designers working together on the creation and performance of graphic scores. He writes of concerns shared by composers Pierre Boulez and John Cage: “Problematizing the idea of chance, [the new graphic scores] afford performers a certain freedom of choice, and a site of possibilities.” On an optimistic note, Akiyama concludes: “If putting signs in a white space means producing a new acoustic space, what a free painting that is.” Illustrations include part of Takemitsu Toru’s score for “Corona for Pianists.”

Publication: 「記号変革の意味——グラフィズムの楽譜をみて」 Yomiuri Shinbun, Evening edition, 7

Language: Japanese

Nature and Music 2

by Ichiyanagi Toshi, March 1962

In part two of a three-part series of essays, Ichiyanagi discusses his own graphic scores as well as scores by John Cage, Matsudaira Yoriaki, Takahashi Yuji, Yuasa Joji, and Takemitsu Toru. Ichiyanagi argues that this new form of notation places a premium on process and experience (the “natural way of music,” as he puts it) rather than on the inscribed score as the final product by the composer as author. Includes images of scores by Ichiyanagi, Cage, Matsudaira, Takahashi, Yuasa, and Takemitsu.

Publication: 「自然と音楽 2」 Ongaku-Geijutsu 20(3), 14−19, 47

Language: Japanese

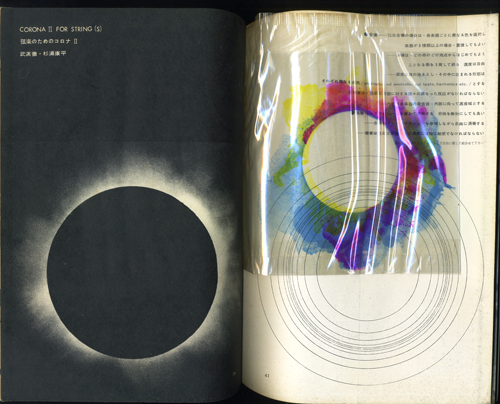

Corona for Strings II

by Takemitsu Toru & Sugiura Kohei, April 1962

Devoted to the theme “Contemporary Image,” this issue of the journal Bjutsu Techo includes a graphic score co-created by composer Takemitsu Toru and graphic designer Sugiura Kohei. The reproduction is notable in that it is a facsimile copy of the score rather than a partial or reduced illustration.

Publication: 「弦楽のためのコロナ II」 Bijutsu Techo 203, 34−41

Language: Japanese

Nature and Music 3

by Ichiyanagi Toshi, May 1962

In the final part of a three-part series of essays, Ichiyanagi focuses on the notion of time in contemporary music. Asking what kinds of time besides clock-time are possible, he writes about the endeavors of musicians such as John Cage, Yoko Ono, Tone Yasunao, Takehisa Kosugi, and LaMonte Young, who are seeking new conceptions of time through practices involving graphic notation, chance, and indeterminacy. At the end of the article, an announcement of an exhibition of graphic scores at the Tokyo Gallery includes a list of works by the four featured composers. Includes illustrations of scores by Cage and Tone, respectively, and installation views of works by Yoko Ono and Gruppo T.

Publication: 「自然と音楽 3」 Ongaku-Geijutsu 20(5), 23−27

Language: Japanese

Exhibition of 4 Graphic Composers

by Akiyama Kuniharu, May 1962

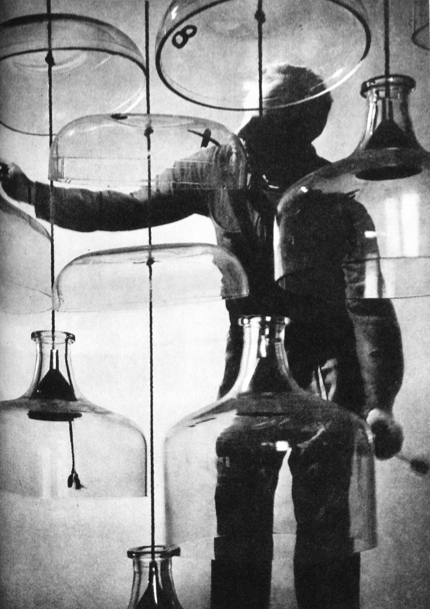

Setting aside his customary enthusiasm, Akiyama pans the exhibition of graphic scores at Tokyo Gallery (4 Composers—Exhibition of Graphic Scores). He describes the exhibition as hedonistic and opportunistic, overly focused on visual prettiness and spectacle (“Real live tadpoles! Toys hanging on strings!”), and missing the opportunity to engage with the new creative possibilities afforded by graphic scores.

Publication: 「4人のグラフィック楽譜展」 SAC 24, n.p.

Language: Japanese

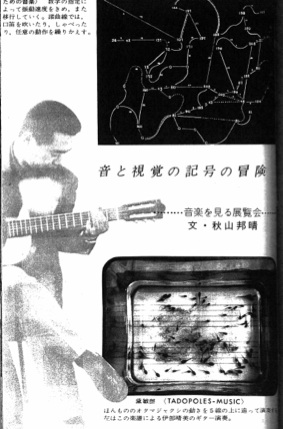

From the Exhibition of Four Composers—An Adventure in Signs of Sound and Vision

by Akiyama Kuniharu, June 1962

A reflection on the exhibition 4 Composers—Exhibition of Graphic Scores at Tokyo Gallery featuring images of scores by Ichiyanagi Toshi, Mayuzumi Toshiro, Takemitsu Toru, and Takahashi Yuji, and accompanied by brief explanations of how to interpret the works. One of the illustrations includes guitarist Ibe Harumi playing Mayuzumi’s “Tadpole Music.” Adopting a more positive tone than the one he used in his review of the same exhibition, published in the May issue of the SAC Journal (see above), Akiyama discusses the profound significance of graphic scores for new ways of thinking about music. However, he reiterates his desire for the show’s four composers to translate these new concepts into audible musical results rather than fixating on the heightened visual interest in the scores.

Publication: 「『4人の作曲』展より 音と視覚の記号の冒険」 Bijutsu Techo 205, 39−43

Language: Japanese

Tripping up at the Front Lines: Yoko Ono’s Avant-Garde Show

by Donald Richie, July 1962

In this essay Donald Richie, working in Japan as a filmmaker and active participant in the experimental arts scene, launches a vitriolic attack against Yoko Ono’s concert at the Sogetsu Art Center. Richie accuses Ono of lacking originality and stealing from the work of others. The program consisted of pieces performed using instruction-based scores that challenged conventional ideas about music, originality, and aesthetic judgment.

Publication: 「つまづいた最前線——小野洋子の前衛ショー」 Geijutsu Shincho 13(7)

Language: Japanese

A Voice from the Front Line: A Response to Donald Richie

by Ichiyanagi Toshi, August 1962

In an eloquent response to Donald Richie’s harsh critique of Yoko Ono’s concert at the Sogetsu Art Center (see above), Ichiyanagi defends Ono and explains her position within the international avant-garde, citing established artists such as John Cage and Morton Feldman, who have expressed admiration for her work, and noting her recent invitations to participate in concerts and exhibitions in Europe and the U.S. Ichiyanagi describes the contributions her work has made to current conversations about temporality and the roles of the audience, performer, and composer in avant-garde and experimental music.

Publication: 「最前衛の声—ドナルド・リチイへの反論」 Geijutsu Shincho 13(8), 60−61

Language: Japanese

Seeing Music

by Sugiura Kohei, August 1962

Writing from the perspective of a designer, Sugiura regards his contributions to the creation of Takemitsu’s “Corona for Pianists” and “Corona for Strings II” as visual solutions to the composer’s ideas. For Sugiura, it doesn’t matter if the result is called a “score”; what is important is that the result be seen and handled by the interpreter, who may produce one of many possible orderly systems based on the object. The ideal design, he writes, is “a site that allows a person to explore freely the possibilities of self-expression.”

Publication:「見る音楽」 Geijutsu Shincho 13(8), 112−113

Language: Japanese

I Am Tired of Avant-Garde Art

by Hariu Ichiro, August 1962

Revisiting a panel on “The Present and Future of the Avant-Garde” moderated by the critic Hariu Ichiro, the article begins with excerpts from starkly contrasting statements by Yoko Ono and Takahashi Yuji about the current avant-garde. Other panel participants include composer Ichiyanagi Toshi and members of the Neo-Dada group. Noting the proliferation of conflicting statements about the avant-garde, Hariu expresses doubts about the usefulness of “avant-garde” as a label as well as about the role that avant-garde art plays in contemporary society. Includes images of performances by Ichiyanagi at the 4 Composers exhibition at the Tokyo Gallery, including “Tadpole Music” by Mayuzumi and works by Shinohara Ushio, Kikuhata Mokuma, Yoshimura Masunobu, and installation views of the Yomiuri Independent exhibition.

Publication:「前衛芸術に疲れました」 Geijutsu Shincho 13(8), 148−153

Language: Japanese

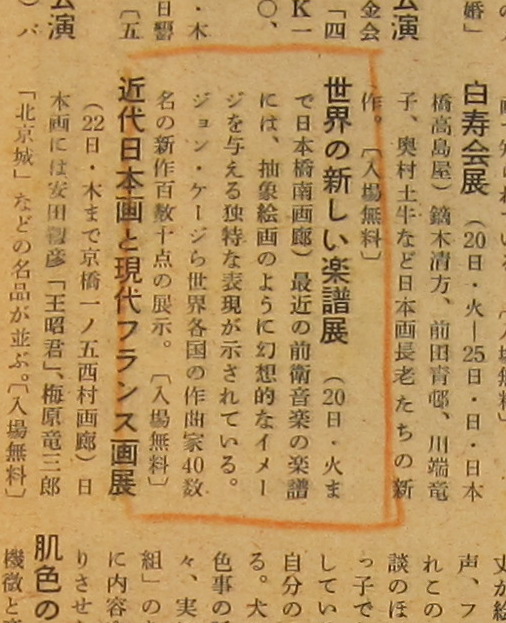

Announcement for Exhibition of WGS: Body text—”An exhibition of more than 100 new works by John Cage and more than 40 composers from around the world”

November 1962

A newspaper announcement for the Exhibition of World Graphic Scores. A clipping of the announcement, along with a fragment of a news page dated November 19, 1962, was inserted into the notebook in which Akiyama Kuniharu laid out the plans for this exhibition.

Publication:本文より「ジョン・ケージら世界各国の作曲家40数名の新作百数十件の展示」 Shukan Shincho, 18

Language: Japanese

An Exhibition of World Graphic Scores—A Return to Zero

By Yano Junichi, November 25, 1962

In a review of the Exhibition of World Graphic Scores, Yano Junichi celebrates the event for bringing together works by important figures in experimental music from Japan and around the world. Comparing the new form of notation to work by action painters, Yano writes that graphic notation allows composers to “return to primary sensations” and access the nature of sound itself.

Publication:「世界の新しい楽譜展——ゼロへの回帰」 SAC Journal, no. 27, n.p.

Language: Japanese

Round Table: An Inquiry into Graphic Scores—Around Recently Performed Works

By Ichiyanagi Toshi, Kobayashi Kenji, Kumagai Hiroshi, Takahashi Yuji, Yamaguchi Koichi, Akiyama Kuniharu July 1963

Performers, composers, and critics participating in the roundtable discussion address the significance of recently performed works that employ graphic notation. Violinist Kobayashi speaks of practical issues surrounding performance, while Takahashi wonders about the aesthetic and philosophical significance of graphic notation for the new music of chance and indeterminacy. They discuss pieces performed on July 3, 1963, at the Sogetsu Art Center (Sogetsu Contemporary Series 21, New Direction ensemble, second concert), including “Phrase à Trois,” by Sylvano Bussotti, “Zyklus,” by Stockhausen, “Drip Music,” by George Brecht, and “Sapporo” by Ichiyanagi Toshi.

Publication:「座談会 図形楽譜の問題——今回の作品を中心に」 SAC Journal, no. 32, n.p.

Language: Japanese

New Direction’s Second Concert, Or, A Critical Reflection on Graphic Scores

By Tone Yasunao, September 1963

Reviewing the July 3, 1963, concert by the New Direction ensemble (see above), Tone suggests that graphic scores such as Sylvano Bussotti’s, which depends on expert performers like David Tudor, harbor regressive tendencies. He contrasts this with Ichiyanagi’s “Sapporo,” which he praises for employing minimal signage and privileging actions by performers engaged in forms of creativity that are not centered on self-expression.

Publication:「ニューディレクション第2回演奏会または図形楽譜への反省」 Ongaku Geijutsu, *in Kagayake, p. 284

Language: Japanese

An Unusual Exhibition

By Hariu Ichiro, April 1974

Reviewing the July 3, 1963, concert by the New Direction ensemble (see above), Tone suggests that graphic scores such as Sylvano Bussotti’s, which depends on expert performers like David Tudor, harbor regressive tendencies. He contrasts this with Ichiyanagi’s “Sapporo,” which he praises for employing minimal signage and privileging actions by performers engaged in forms of creativity that are not centered on self-expression.

Publication:「異色の展覧会」 Geijutsu Seikatsu 296 , 148−149

Language: Japanese