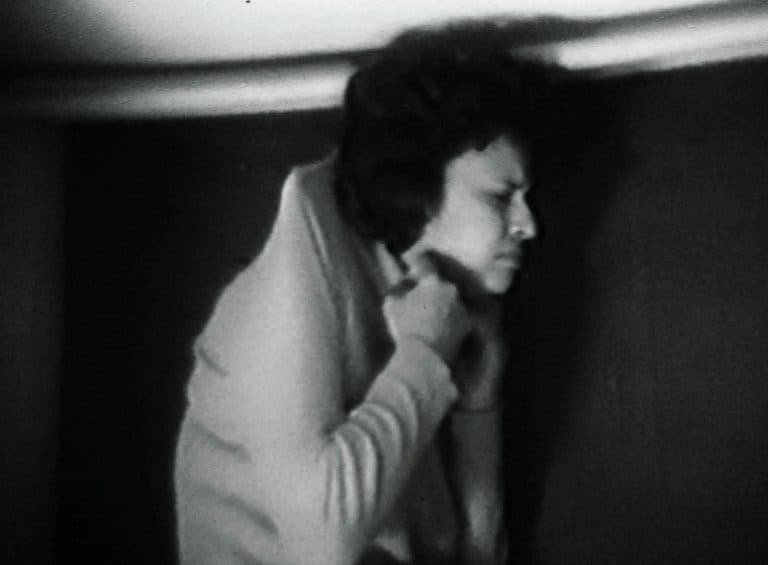

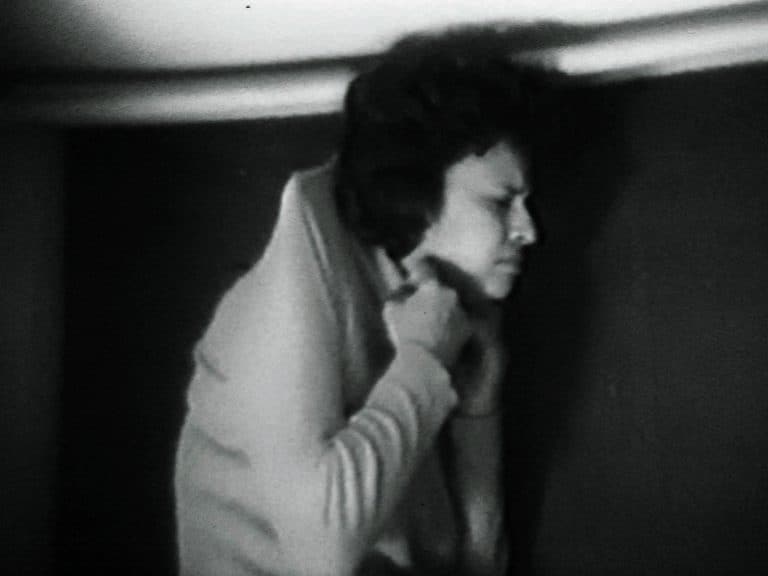

The black-and-white video In, created by Brazilian artist Letícia Parente in 1975, reveals a complex artistic practice. Widely distributed in recent years and now in MoMA’s collection, the two-minute video depicts Parente entering a closet and hanging up her sweater without first removing it from her body. This essay demonstrates how In is an artistic response to the social and political oppression experienced by women living under a patriarchal dictatorship.

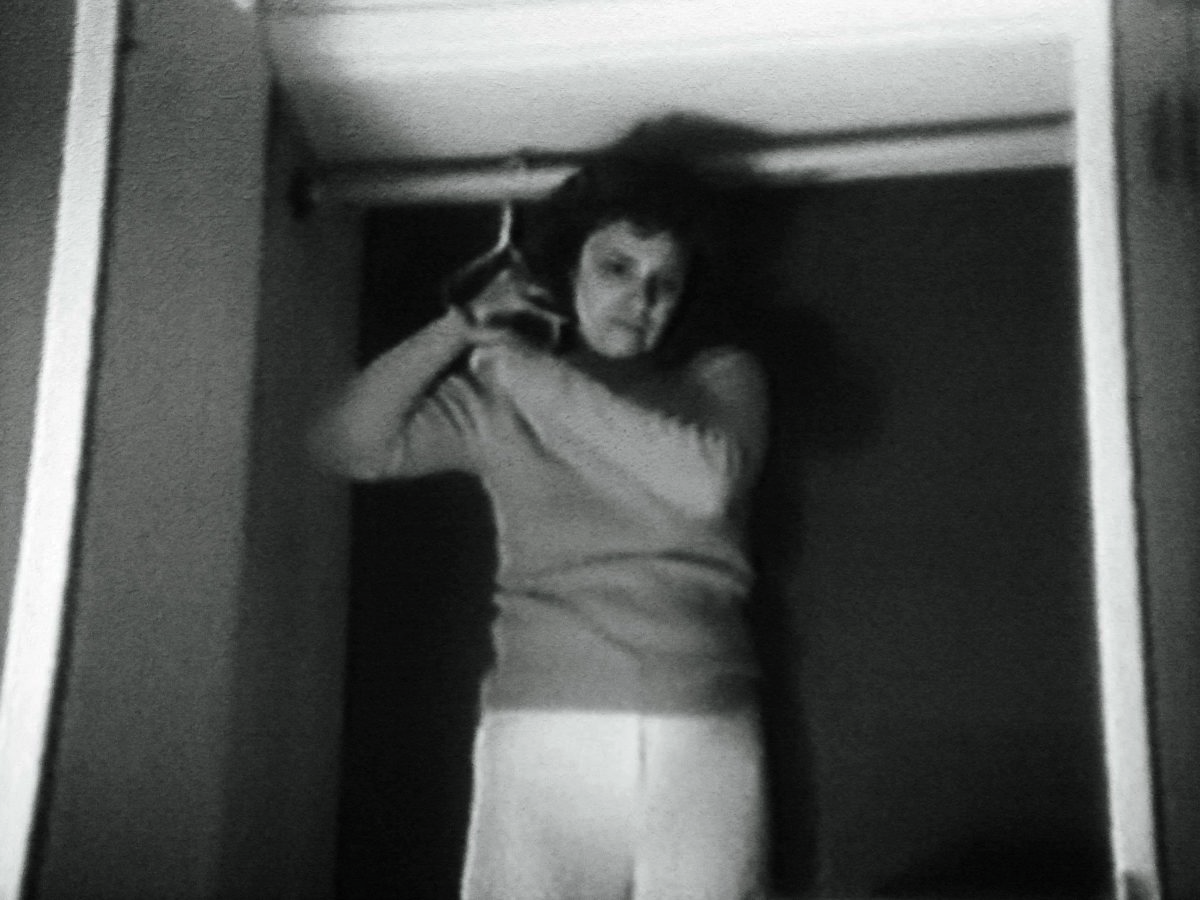

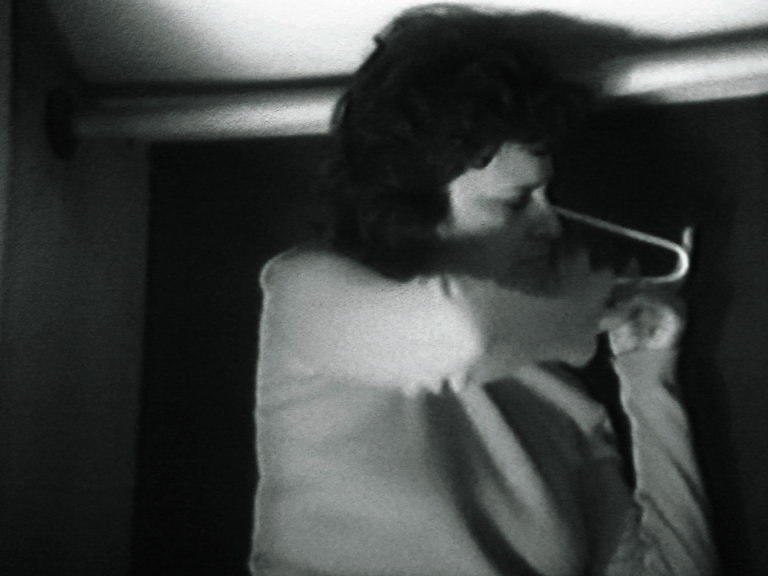

In her two-minute, black-and-white video In, the artist Letícia Parente (1930–1991) enters a room of her own. She opens a pair of white doors, walks through them into a small closet, climbs up the shelves and hangs up her sweater without first removing it from her body. Then, from what seems to be a hanging position, she closes the doors. From the interior of a closet, in the privacy of her home in Rio de Janeiro, Parente sardonically comments on the confining nature of the social and familial responsibilities assigned to women, and in so doing, reflects upon the multiple identities she herself embodies—that of a housewife, mother of five, artist, and chemistry professor in the context of Brazil’s repressive military dictatorship (1964–85). In constitutes a bold exhibition of Parente’s personal and artistic autonomy, offering a variation on the modern art trope of the house as both a metaphor for the constriction of women and a space in which women are able to enact their own will.

In depicts a woman who is highly aware of the staged nature of her action and taking ownership of the physical and metaphorical space she inhabits. This deliberateness echoes that of Marca registrada (Trademark, 1975), Parente’s best-known work, in which she carefully stitches the words “Made in Brasil” [sic] into her foot. While in one video Parente methodically sews her own skin with a needle and thread, in the other, she weaves a hanger through a sweater she is wearing. In evidences the calculated nature of Parente’s undertaking in both the single hanger occupying the closet and the choice of a long-sleeve turtleneck—as if the artist is purposefully disregarding the perpetually warm climate of Rio de Janeiro, where the video was recorded, and the difficulty of hanging a garment that is still being worn. Her body poses an obvious obstacle to hanging the sweater, but despite her visible discomfort, much like that implied in Marca registrada, Parente’s voluntary movements are perfectly controlled.

Deploying her own body as the subject of her work, Parente videotapes her actions to be preserved and exhibited for others to see: The English word in—carefully chosen for an international audience—calls attention to the constraints faced by a woman living under Brazilian military rule. By underscoring the limitations on her movement, Parente alludes to the everyday control exerted by a military government and materialized in censorship, travel restrictions, and nationwide educational reforms. Yet at the same time, her actions represent the liberties that an artist can reclaim through creative production. In frames the orchestrated gestures of a woman who locks herself away in order to renounce, if only temporarily, her simultaneous roles as housewife, professor, and mother—and the social expectation that she will raise and educate model Brazilian citizens. Over the course of this short video, Parente opts to be accountable only for her own person, even if this requires hanging her body up in a closet.

A comparison between Parente’s slide show Auto-retrato (Self-Portrait, 1975) and In sheds light on the multiple realms that a woman is made responsible for, and on the series of people and objects that would be affected by her absence. Despite formal differences between the two works, visual parallels between Auto-retrato—in which a succession of objects and people are deliberately arranged in a closet and displayed in discrete sequence—and In make clear the latter’s connections to this slideshow. Among Brazilian artists in the early 1970s, the slideshow was a popular medium, often enhanced by an audio component provided by a cassette recorder.1For the use of slide shows by Parente’s contemporaries in Brazil, see Sonia De Laforcade, “Click, Pulse: Frederico Morais and the Comparative Slide Lecture,” Grey Room 73 (Fall 2018), 96–115; and Roberto Moreira S. Cruz, “Projeções de imagens: pioneiros do audiovisual experimental no contexto da arte brasileira,” in Filmes e vídeos de artistas, Coleção Itaú, exh. cat. (Porto Alegre: Fundação Iberê Camargo, 2016), 84. Indeed, Auto-retrato was composed of twenty-eight slides, each of which was projected for five seconds, and rotated against eight different recorded sounds for a total duration of 210 seconds, or three and a half minutes.2Letícia Parente’s handwritten annotations, Letícia Parente personal archive. The difference between the slide’s projected time and the total time of the slideshow Auto-retrato results from the mechanical nature of the projector: it takes about two seconds to move from one slide to the next. The depicted objects and people ranged from a selection of cleaning products to food to Parente’s children to Parente herself. Though the slideshow itself has not been preserved, some of the photographs within it exist as individual images.3For photographs used by Letícia Parente in Auto-Retrato, see André Parente’s digital re-creation Eu armario de mim, https://vimeo.com/92756529. Based on these surviving photographs and Parente’s personal accounts, and given the similar structure and visual composition of the two works, I propose to read In as a video-recorded extension of Auto-retrato.

According to Brazilian critic Frederico Morais, Parente’s Auto-retrato presents the complexities of viewing a person as an archive. In his words, Auto-retrato offers “the closet as a miniaturized portrait of the house, [as an] archive of [the] tensions and pressures experienced by humans.”4“O armário como retrato miniaturizado da casa, arquivo das tensões e pressões que vive o ser humano, hoje.” Frederico Morais, “Audio-visual: nova etapa,” in Diário de Notícias, August 22, 1975. My translation. If the closet is in fact a metonym for the house—much in the same way that In uses the house as a metonym for Brazil—the succession of images comprising what Morais calls an “archive” stands for a store of individual and collective bodily experiences. Paralleling Auto-retrato’s composition, In is the representation of a developing action, or the movement through time of the body, that is, of the body of a woman who chooses to store and lock herself away, and for her own satisfaction, to preserve herself as a testimony—or as an archive, in Morais’s words—that can only be accessed through public contemplation.5In combination with its archival characteristic, In can be seen as a repertoire of knowledge, following performance scholar Diana Taylor’s concept of “repertoire.” See Diana Taylor, The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003), xvii, 36.

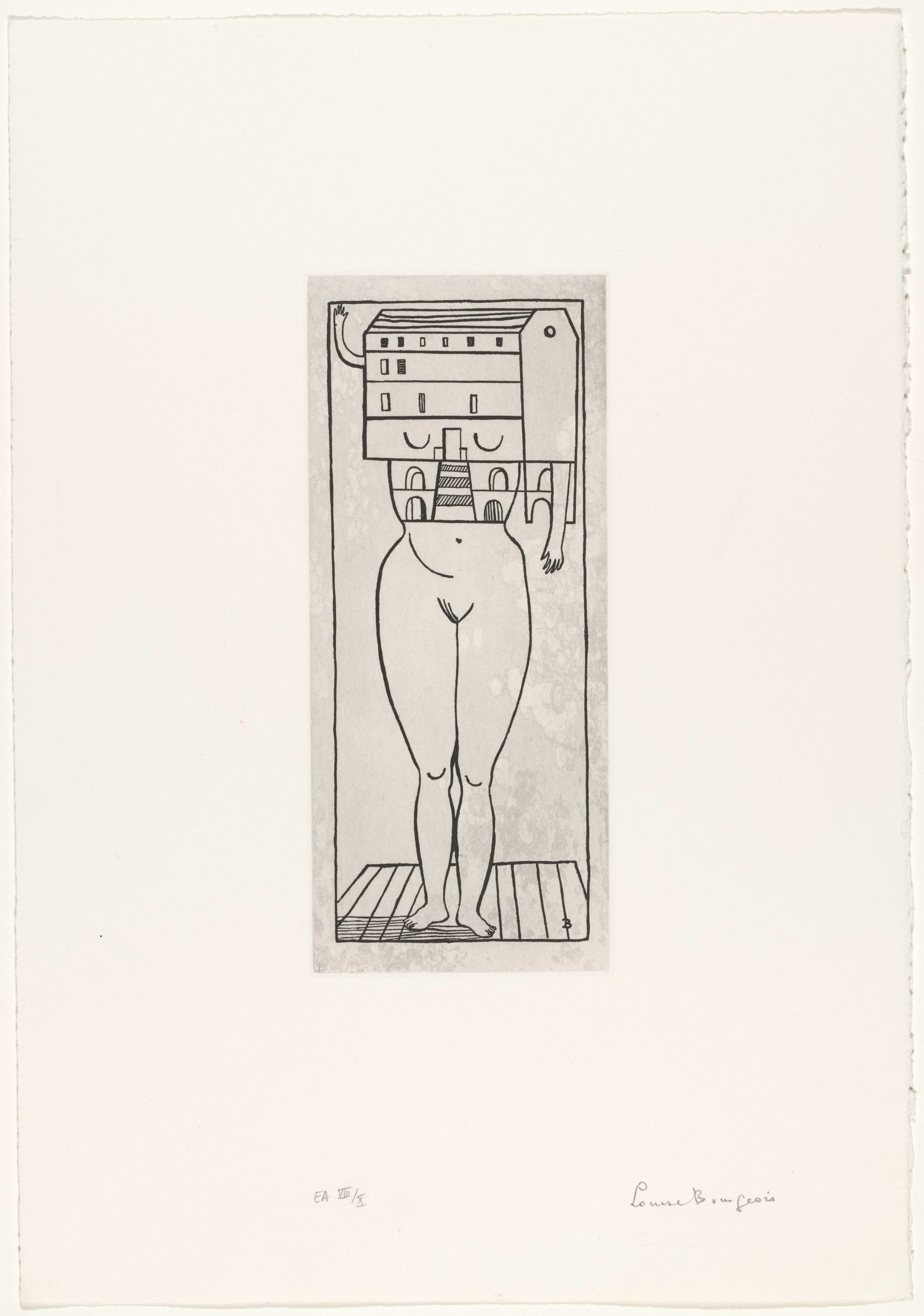

By bearing witness to the restrictions imposed on women’s mobility, and through Parente’s artistic strategies to reclaim her autonomy, In dialogues with other artworks created in the Americas—specifically those in which the image of a house serves as a metaphor for constriction, such as, for instance, Louise Bourgeois’s Femme Maison (etching, 1947) and Martha Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975). In Femme Maison, Bourgeois addresses the physical and psychological restraints forced on women by replacing a woman’s upper body with a small house, an enclosure that stands for the domestic responsibilities of a mother and housewife.6For a discussion of Louise Bourgeois’s Femme Maison in relation to her extensive career and body of work, see Deborah Wye, “Architecture Embodied,” in Louise Bourgeois: An Unfolding Portrait. Prints, Books and the Creative Process, exh. cat.(New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2017), 36–61. Whereas the sturdy architecture of the building depicted in Bourgeois’s print (reinforced by the print’s delineated frame) impacts the potential movement or lack thereof of the woman’s limbs, the architecture of the closet in Parente’s video In allows her the space to dictate the extent of her own range of motion.

Like Bourgeois, Rosler critiques the constraints of determined architectural spaces in her work Semiotics of the Kitchen, yet she does so by explicitly addressing the viewer. Rosler’s presentation of kitchen utensils in alphabetical order and with progressive violence brings increased attention not only to the restrictions of the gendered space of a domestic kitchen but also to a woman’s will to enact change. Semiotics of the Kitchen shares formal qualities with In: both were recorded as black-and-white videotapes; however, Rosler’s work offers the staged effort of women actively subverting the traditional gendered roles ascribed to housewives. If Rosler challenges the viewer by parodying a cooking show, which converts a private space into a public stage, Parente retains the insular character of the domestic realm by bringing us into the intimate, innermost recesses of her household. The titular “In” extends beyond a physical reference to the closet, the house, and the country, in order to reach the woman herself.

Although Parente’s In, Bourgeois’s Femme Maison, and Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen represent three comparable takes on women’s inhabitation of domestic spaces, their varied contexts reveal the different stakes for feminists in different parts of the world. Bourgeois’s print became an icon of second-wave feminism as developed mostly in the United States and Europe when, in 1976—one year after the creation of In—Femme Maison appeared on the cover of art critic Lucy Lippard’s From the Center: Feminist Essays on Women’s Art.7Lucy Lippard, From the Center: Feminist Essays on Women’s Art (New York: Dutton, 1976). Likewise, Rosler’s video partakes in the history of feminism within the same US context in which social justice claims also advocated against the US military efforts in the Vietnam war.

In contrast, feminist engagements were not openly discussed in Parente’s circle, and the militarism addressed by her fellow Brazilian artists, including by Rubens Gerchman, Anna Maria Maiolino, and Antônio Henrique Amaral, was more immediately felt in the South American nation, where a military dictatorship held power for twenty-one years. Parente’s direct peers and colleagues—women artists at work in Brazil during this time—have asserted that they regarded advocating for feminist ideals as frivolous and secondary when facing the realities of an oppressive governmental administration that, between 1968 and 1978, suppressed popular suffrage and habeas corpus.8For more on the rejection of feminism during the 1960s–70s by women artists in Brazil, see Roberta Barros, Elogio ao toque: ou como falar de arte feminist à brasileira (Rio de Janeiro: Relacionarte Marketing e Produções Culturais, 2016). On the suspension of civil rights, the closure of Brazil’s National Congress from December 13, 1968, to December 13, 1978, see “Ato Institucional No 5, de 13 de dezembro de 1968,” Presidência da República, Casa Civil, Subchefia para Assuntos Jurídicos, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/ait/ait-05-68.htm. Just the same, feminism as an ideology advanced in the 1970s by activists like US writer Betty Friedan and supported internationally by the United Nations was not unfamiliar to those living in Brazil.9In 1975, the United Nations–designated International Women’s Year was publicly celebrated in Rio de Janeiro, and efforts by women to reclaim their autonomy were on the horizon. This shift is evidenced by the burst of feminist movements based in intersecting ethnicities and addressing local inequalities amid Brazil’s re-democratization in the mid-1980s. By recording In within her Rio de Janeiro home, Parente proposed that a woman’s autonomy could be reclaimed through the creative actions of an artist who was also a mother, housewife, and professor in a public institution, and who was living under a patriarchal, dictatorial regime. By recording herself in the closet, Parente demonstrates how creating a work of art constitutes a strategy for acting according to one’s own will without constricting the will of others. In stands as Parente’s enactment of a woman’s rejection of the social expectations historically and politically imposed upon her.

- 1For the use of slide shows by Parente’s contemporaries in Brazil, see Sonia De Laforcade, “Click, Pulse: Frederico Morais and the Comparative Slide Lecture,” Grey Room 73 (Fall 2018), 96–115; and Roberto Moreira S. Cruz, “Projeções de imagens: pioneiros do audiovisual experimental no contexto da arte brasileira,” in Filmes e vídeos de artistas, Coleção Itaú, exh. cat. (Porto Alegre: Fundação Iberê Camargo, 2016), 84.

- 2Letícia Parente’s handwritten annotations, Letícia Parente personal archive. The difference between the slide’s projected time and the total time of the slideshow Auto-retrato results from the mechanical nature of the projector: it takes about two seconds to move from one slide to the next.

- 3For photographs used by Letícia Parente in Auto-Retrato, see André Parente’s digital re-creation Eu armario de mim, https://vimeo.com/92756529.

- 4“O armário como retrato miniaturizado da casa, arquivo das tensões e pressões que vive o ser humano, hoje.” Frederico Morais, “Audio-visual: nova etapa,” in Diário de Notícias, August 22, 1975. My translation.

- 5In combination with its archival characteristic, In can be seen as a repertoire of knowledge, following performance scholar Diana Taylor’s concept of “repertoire.” See Diana Taylor, The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003), xvii, 36.

- 6For a discussion of Louise Bourgeois’s Femme Maison in relation to her extensive career and body of work, see Deborah Wye, “Architecture Embodied,” in Louise Bourgeois: An Unfolding Portrait. Prints, Books and the Creative Process, exh. cat.(New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2017), 36–61.

- 7Lucy Lippard, From the Center: Feminist Essays on Women’s Art (New York: Dutton, 1976).

- 8For more on the rejection of feminism during the 1960s–70s by women artists in Brazil, see Roberta Barros, Elogio ao toque: ou como falar de arte feminist à brasileira (Rio de Janeiro: Relacionarte Marketing e Produções Culturais, 2016). On the suspension of civil rights, the closure of Brazil’s National Congress from December 13, 1968, to December 13, 1978, see “Ato Institucional No 5, de 13 de dezembro de 1968,” Presidência da República, Casa Civil, Subchefia para Assuntos Jurídicos, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/ait/ait-05-68.htm.

- 9In 1975, the United Nations–designated International Women’s Year was publicly celebrated in Rio de Janeiro, and efforts by women to reclaim their autonomy were on the horizon. This shift is evidenced by the burst of feminist movements based in intersecting ethnicities and addressing local inequalities amid Brazil’s re-democratization in the mid-1980s.