Art historian Alise Tifentale considers the difficulties of preserving and interpreting the legacy of Latvian artist and photographer Zenta Dzividzinska (1944–2011). In the 1960s, Dzividzinska was one of the few women photographers in Riga whose work was highly regarded in the local and international photo club culture. Her most significant contribution is a collection of images capturing the daily life of three generations of women living in a small house in the country. These photographs have remained largely unknown until recently. This essay highlights the sociopolitical and cultural motives for such neglect and suggests avenues of further research of the artist’s estate.

The jar of blackberry jam from the summer of 2010, the last batch my mother ever made, still sits in the fridge in my Riga apartment. As far as I know, my mom, Latvian artist and photographer Zenta Dzividzinska (1944–2011), chose the garden as her place of creativity and comfort, especially after her husband—my father, painter Juris Tifentals (1943–2001)—had passed away. Quite opposite to the clean and orderly rows of her garden, the state of her artistic output at the time of her passing was that of utter chaos. Among the reasons for such disarray were three decades of neglect, followed by two decades of attempts, in response to random requests from a few curators and researchers, to pick out “something interesting” from her archive of negatives, vintage prints, and documents. Now, almost ten years after my mother’s death, I have returned to Riga to enter the storage unit, to try to bring some sort of order to the contents of the numerous boxes, and to make her archive available in its entirety.

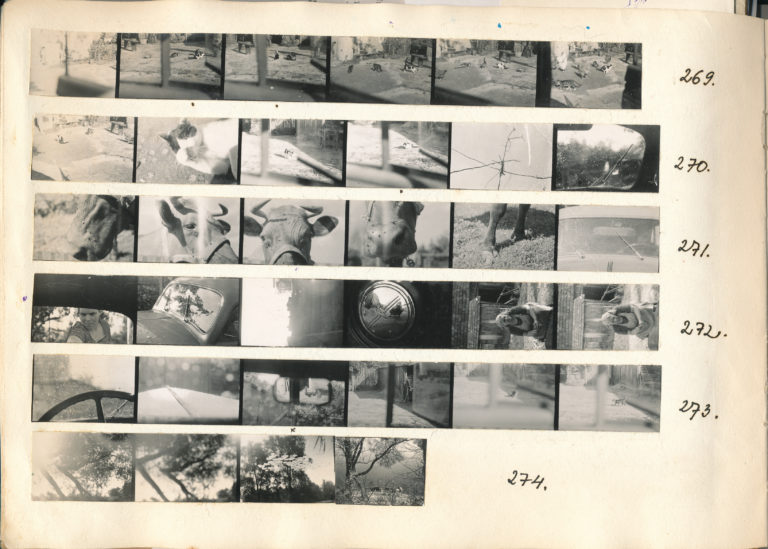

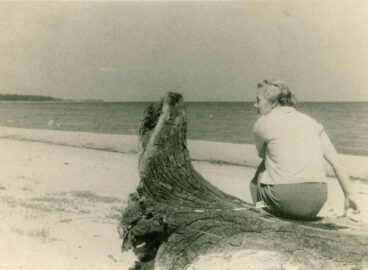

This essay introduces the life and career of Zenta Dzividzinska, or ZDZ (my mother, annoyed by having to spell out her long, Polish-sounding last name, which was rather unusual in Latvia, liked to sign with this abbreviation), focusing on her artistic output of the 1960s and early 1970s. At the center of this body of work is a vast collection of images that she later titled House Near the River, which were made in and around her parents’ home on the outskirts of Iecava, a village less than an hour’s drive south of Riga. During the 1960s, while studying art in Riga and working, ZDZ often visited her parents and extended family there. Later, she returned to the house to live in it permanently with her husband, whom she married in 1969.

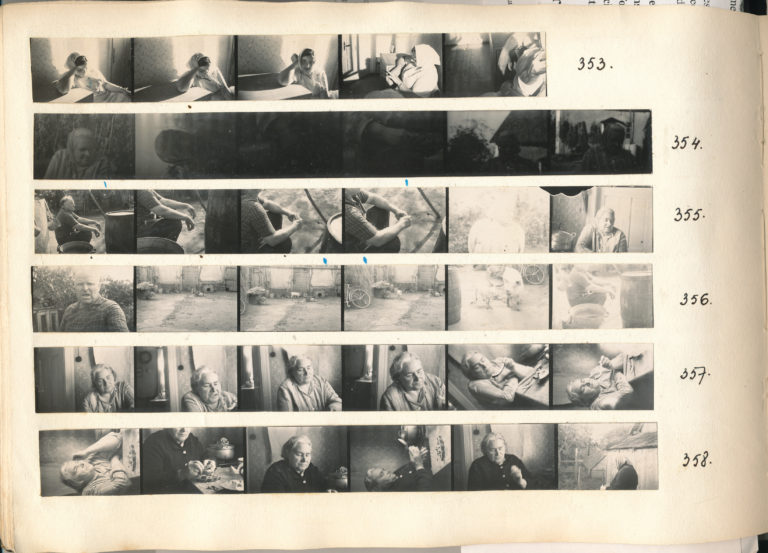

House Near the River comprises hundreds of negatives and prints depicting the daily life of three generations of women as it unfolded in and around their small house in the Latvian countryside. Today these images can be viewed perhaps as para-feminist (to use Amelia Jones’s term) because explicitly feminist critique did not emerge in Latvian art until the 1980s.1See Amelia Jones, Self/Image: Technology, Representation, and the Contemporary Subject (New York: Routledge, 2006).

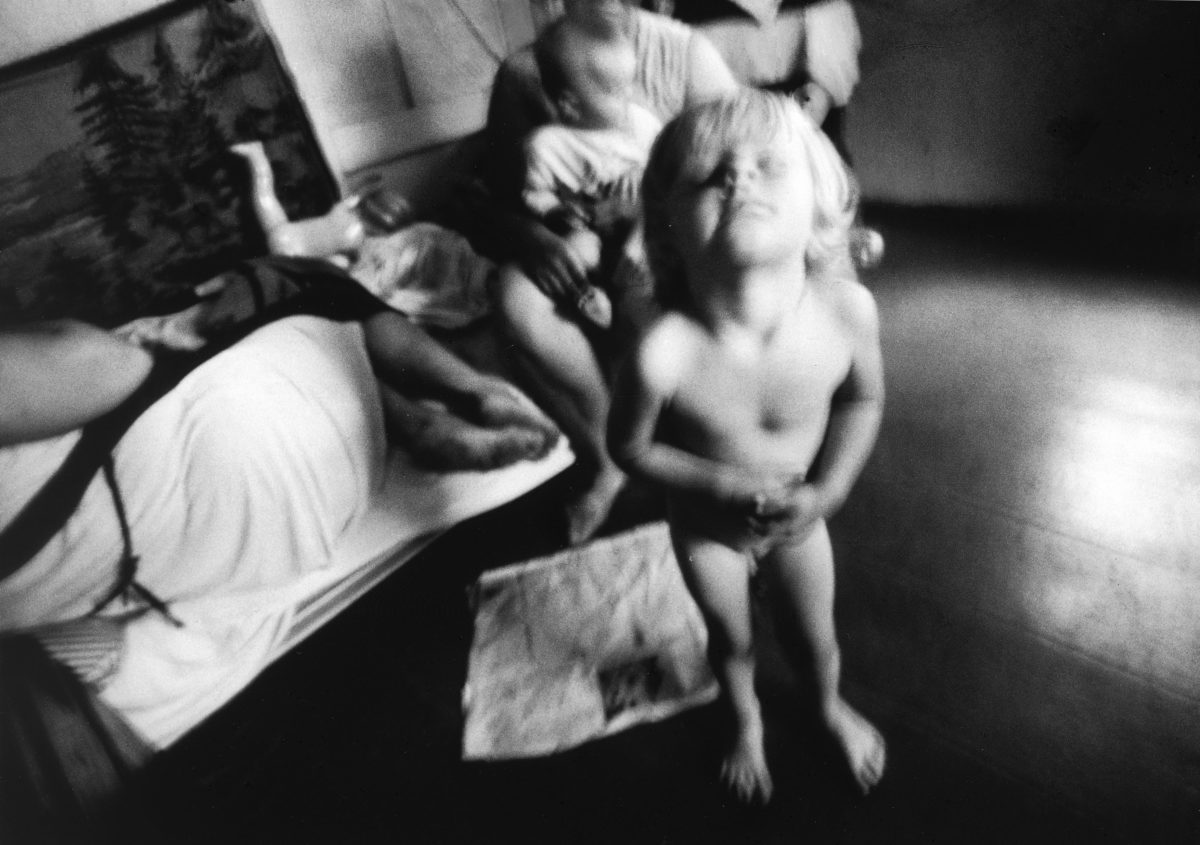

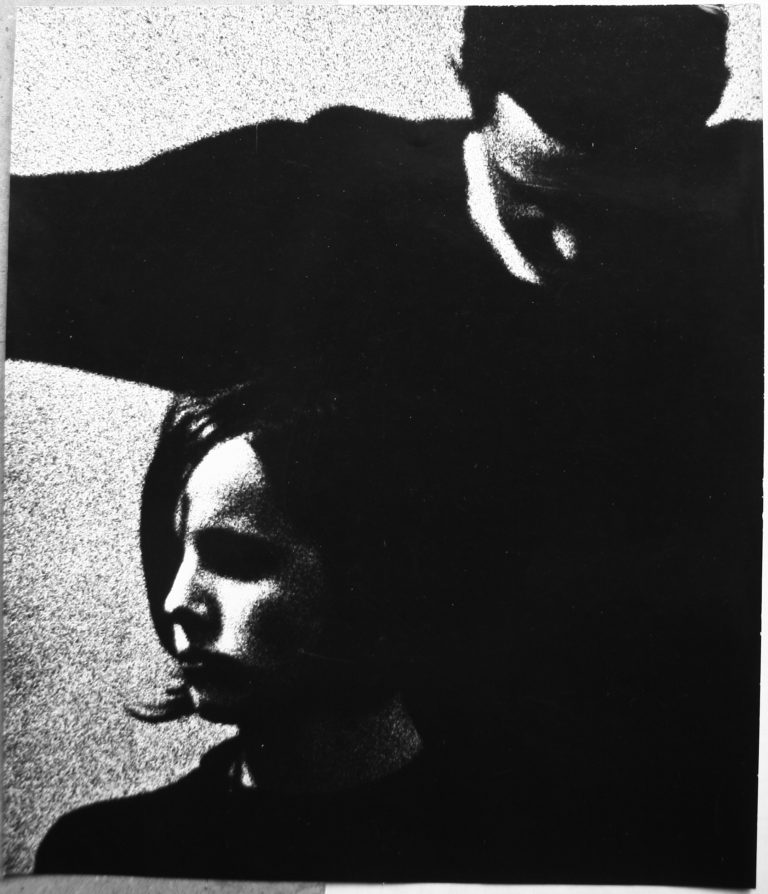

In the most striking images from House Near the River, we see heavyset women and their children, who are at times half dressed, and some men, all of whom are engaged in their daily routines. Their activities include slaughtering pigs and taking blissful-looking naps in the shade, washing babies and laundry in the backyard under the open sky, chopping cabbage for fermenting, and so on. What would be the most shocking for the cohort of ZDZ’s mostly male peers is that the women in her images are not intended to be sources of visual pleasure for a heterosexual male spectator, as was common in the photographic art of the 1960s. Instead, they appear as self-sufficient individuals, preoccupied with their chores and not performing for the camera.2See Inga Šteimane, “Version of Time Machine,” in Black and White, by Zenta Dzividzinska (Riga: Čiris, 1999), n.p.; and Inga Šteimane, “Autobiogrāfiskā arheoloģija,” Studija 9, no. 4 (1999): 100–105. The scenes from the family’s backyard are, as Līga Lindenbauma puts it, “framed in a seemingly random manner and completely rejecting the more traditional principles of composition . . . oblique, searching for new viewpoints, and manifesting an interest in specifically photographic attributes—framing, angle, deformation or movement.”3Līga Lindenbauma, “Paralēlās plūsmas 1960. – 1980. gadu Latvijas fotogrāfijā,” Foto Kvartāls, no. 6 (26) (December 2010): 8. Though critics have struggled to interpret the meaning and visual language of ZDZ’s photographs, the images “remain narratively inconclusive,” as Mark Allen Svede observes.4Mark Allen Svede, “On the Verge of Snapping: Latvian Nonconformist Artists and Photography,” in Beyond Memory: Soviet Nonconformist Photography and Photo-Related Works of Art, ed. Diane Neumaier (New Brunswick, NJ, and London: Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum and Rutgers University Press, 2004), 237. Inga Šteimane writes of ZDZ’s “wandering” and “non-purposeful” lens, while Ieva Astahovska finds “a striking impression of an unposed, unrefined, sometimes blurred, seemingly incidental picture.”5Šteimane, “Version of Time Machine,” n.p.; Ieva Astahovska, “Stories about Forgetting. And Remembering,” Studija 46, no. 2 (2006): 89.

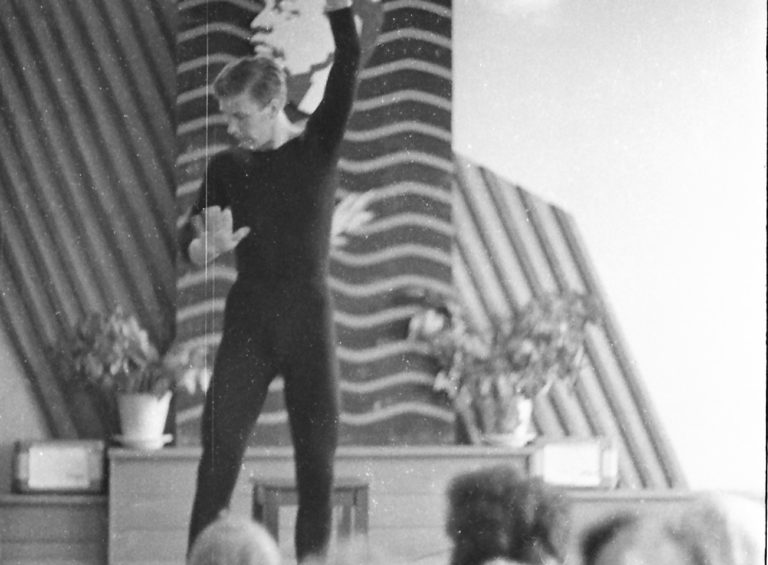

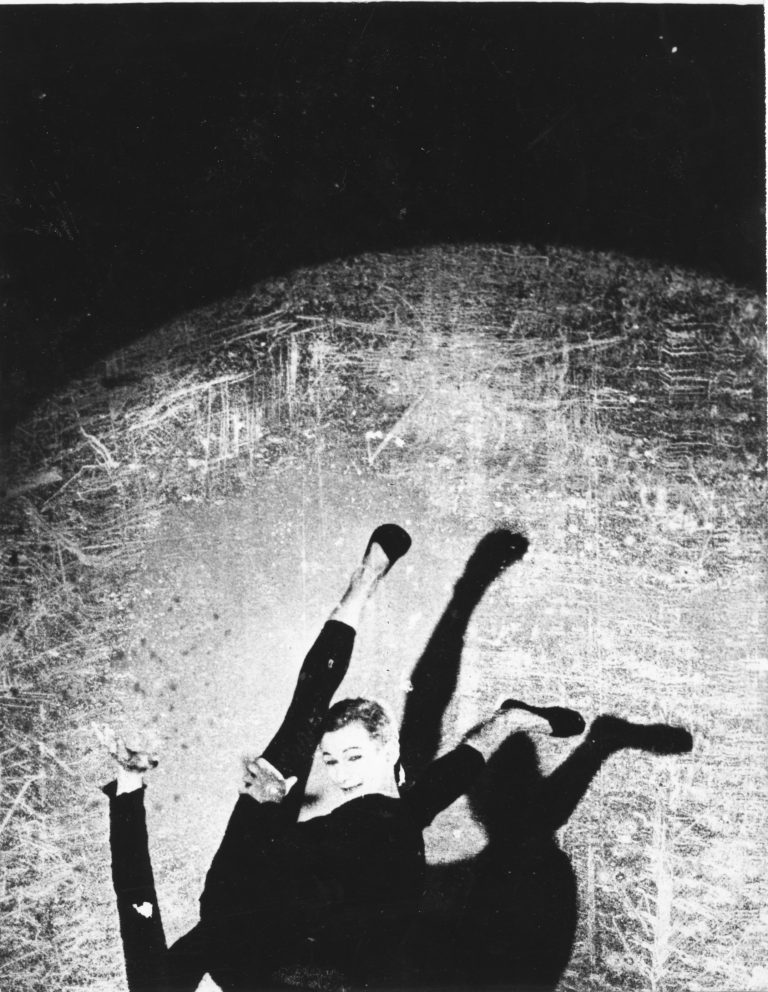

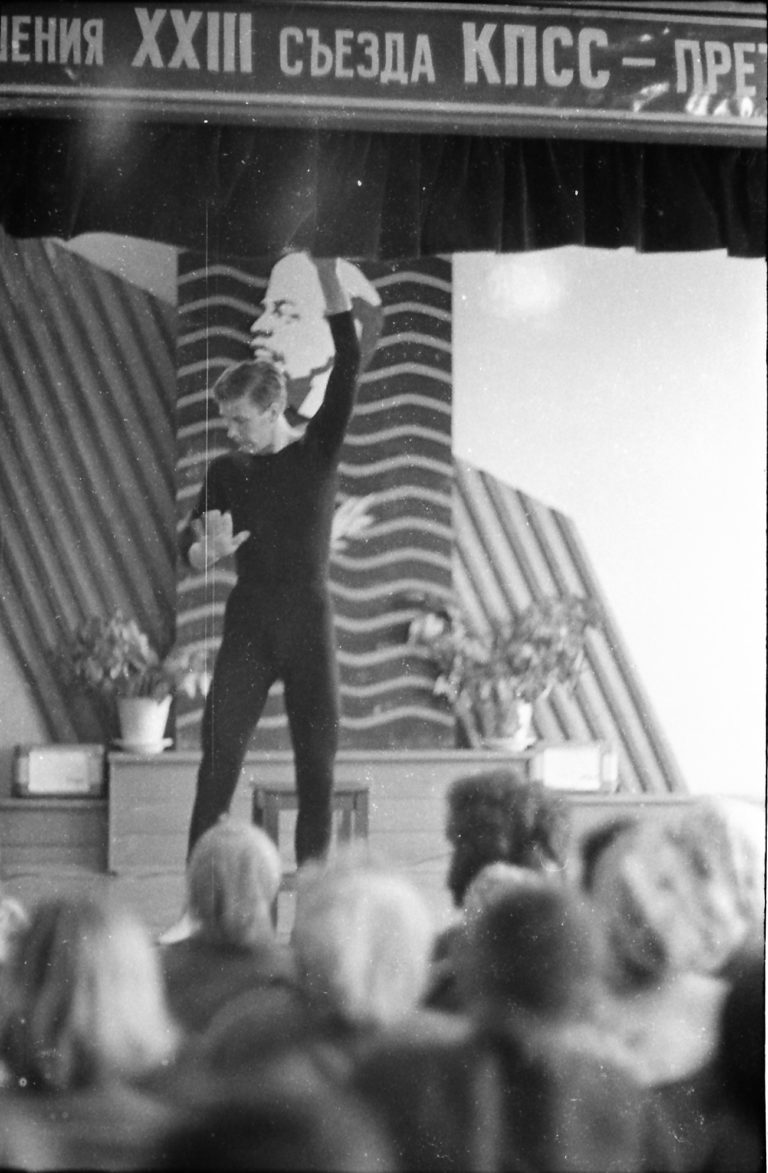

ZDZ became fascinated by photography while studying in 1961–66 at the Riga School of Applied Arts, the local equivalent of the Bauhaus at the time. In 1964 she took an extracurricular photography class taught by Gunārs Binde, one of the most visible champions of photographic art and a leading member of the photo club Rīga. The club’s significance in the Riga art scene of the 1960s and ’70s can be compared to that of the Foto Cine Clube Bandeirante in São Paulo in the 1950s.6See Sarah Hermanson Meister, Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography and the Foto-Cine Clube Bandeirante, 1946–1964 (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2021). See also Alise Tifentale, “Introduction to José Oiticica Filho’s ‘Setting the Record Straighter,’” ARTMargins 8, no. 2 (June 2019): 105–15, https://doi.org/10.1162/artm_a_00239. Moreover, in the Soviet Union of the 1960s, the photo club circuit offered the only legitimate context for exhibiting photographs as an art form. Binde encouraged ZDZ to join the photo club Rīga in 1965. Among one of the very few women in the highly competitive and patriarchal circle of photographers in the club, she succeeded in earning the respect of fellow members while still in her twenties. Arguably, among the main reasons, was the acceptance of several of her prints in the international photo club exhibitions in faraway locations including Tokyo, Singapore, and Kuala Lumpur. For photographers trapped inside the Soviet Union, the vicarious overseas travels of their prints were the highest form of acclaim.7For a discussion of the significance of the photo club culture in the postwar world, especially in the regions outside North America and Western Europe, see Alise Tifentale, The “Olympiad of Photography”: FIAP and the Global Photo-Club Culture, 1950–1965 (PHD diss., Graduate Center, City University of New York, 2020), https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3537. The prints that brought ZDZ recognition fit well within the aesthetics of the photo club culture: a female nude, horses in a meadow, a few images from her series Riga Pantomime (1964–66). However, after she dropped out of the regular photo club activities in the 1970s, her name was soon forgotten, and the artist herself did not revisit her archive until the end of the 1990s.

The photo club culture was not able to fully embrace ZDZ’s independent vision, because ZDZ never identified as a “photographer” but rather as an “artist.” In addition to her studies at the Riga School of Applied Arts, she completed the preparatory course offered by the State Art Academy of the Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1965–67. After that, she did not pursue the Art Academy degree that would have potentially opened the door to a more secure and established art career. At the time, only graduates of the Art Academy were rewarded with state commissions and museum acquisitions, along with access to studios, better housing, and numerous other privileges. The benefits, however, came with certain limitations and demands that the Soviet system imposed on professional artists. Moreover, photography was not among the mediums one could study at the academy. ZDZ chose a less public and more mundane career at the margins of the art world—that of a graphic designer at the state-owned company Māksla (Art), where she worked from 1967 until the company’s dissolution in 1993.

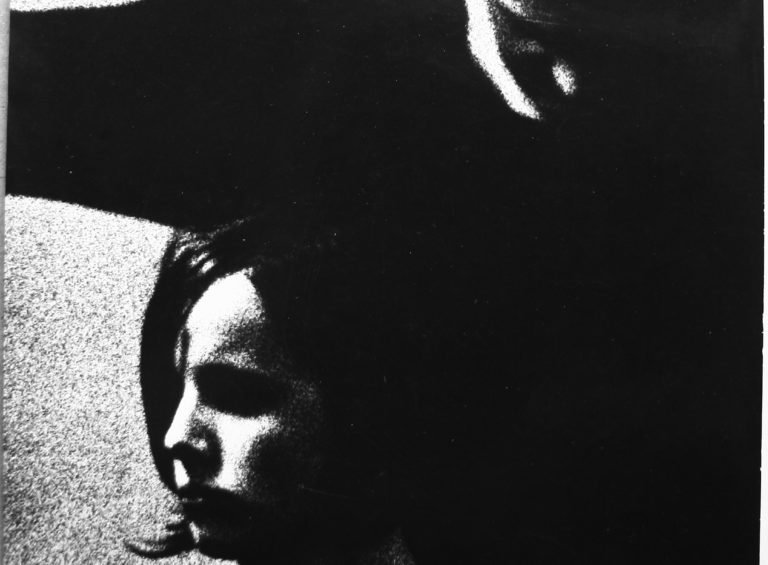

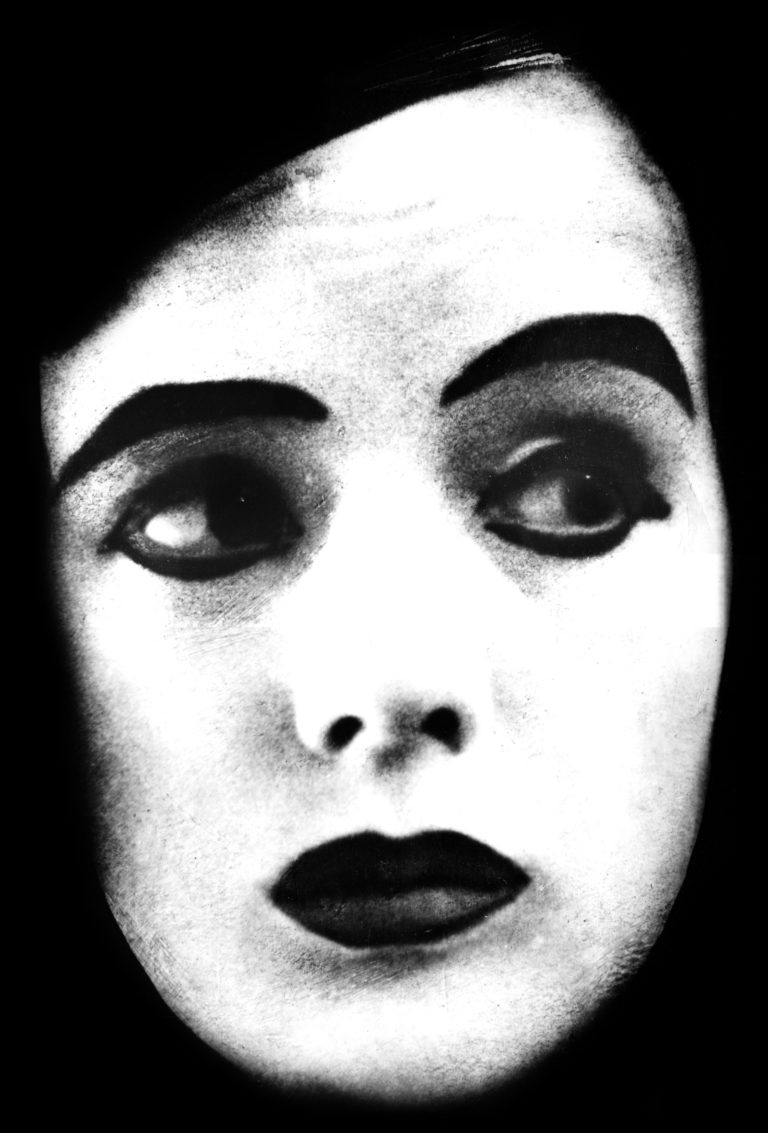

In the 2000s, when ZDZ reminisced about her time in the photo club Rīga, she expressed being skeptical of her technique- and technology-obsessed peers, who were concerned with the sharpness and other mechanical or chemical qualities of the photographic negative and print at the expense of their subject matter, which was oftentimes banal and sentimental. For ZDZ, photography was never about the cameras, lenses, filters, films, or darkroom techniques. To her, photography was just a tool to make images that were interesting to herself. The images did not need to be “pretty”—even when her subject matter was herself. Looking at her Self-Portrait (1968), Svede observes “an artist too bemused by self-portraiture’s potential for self-aggrandizement to even bother sitting up straight or addressing the camera.”8Svede, “On the Verge of Snapping,” 237. ZDZ’s self-portraits, predating the subgenre of self-portraiture known as the selfie by some forty-five years or more, subvert the idea of performative presentation of the self. Instead, they offer unflattering but unusual renderings of the artist’s face and body, employing photographic and optic means such as fish-eye lenses or distorting reflections.

The sad state of ZDZ’s archive stems from the fact that neither her life nor her work had ever been considered particularly valuable. Not unlike what Pierre Bourdieu saw in France during the 1960s, the cultural status of a photographer in the Soviet Union was frequently measured by the cultural status of their subjects.9See Pierre Bourdieu et al., Photography: A Middle-Brow Art, trans. Shaun Whiteside (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990), first published in French as Un art moyen: essai sur les usages sociaux de la photographie (Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1965). Because ZDZ chose her mother, her sister and nieces, and her friends as her protagonists, as opposed to well-known artists, actors, and other public figures of her time, she did not rank as a notable or respectable photographer to her peers. Similarly, her self-commissioned creative work was perceived to have little-to-no cultural value. Most of the images in the series House Near the River can be viewed as an artistic gesture or statement with zero likely spectators. “Photographic art,” as it was understood in the Soviet Latvia of the 1960s, was not supposed to look like this. There was no institutional framework or intellectual context in which a young woman from Riga could exhibit such images and expect to be understood. ZDZ continued working for a decade, perhaps fueled by her own excitement about the possibilities of the photographic medium to capture and defamiliarize reality. But the excitement faded away when she faced the need to provide for her family—and to prioritize paid work over her experiments with photography. In the 1970s, she put the negatives, prints, exhibition catalogues, books, equipment, and photo-related ephemera in the attic. Growing up in the 1980s and early 1990s, I had no idea that my mother used to be a photographer.

Some interest in ZDZ’s work emerged in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Šteimane inspired her to organize what was the artist’s second solo show since 1965, an exhibition entitled Black and White, which featured a few images from House Near the River (Riga, gallery Čiris, 1999). Svede also selected a collection of ZDZ’s prints for the Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection of Soviet Nonconformist Art at the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University. Interaction with Svede and Šteimane convinced ZDZ to revisit her archive more thoroughly, and to exhibit a selection of images from House Near the River series in what was her third solo show, I Don’t Remember a Thing (Riga, 2005), and then to expand that selection in an eponymous photobook (2007).10Zenta Dzividzinska, I Don’t Remember a Thing. Photographs 1964–2005 (Riga: Artists’ Union of Latvia, 2007). Although the exhibition and book received positive reviews, they did not bring a notable change in the general neglect of her work. The public as well as a large part of the art world regarded ZDZ’s images of women as “not pretty”—that is, as unsightly, unattractive, and ridiculous.

A large part of the mainstream history of twentieth-century modernist photography as we know it comprises performances of femininity in front of the (by default, masculine) camera. Throughout much of the past century, photography both as business and art has been concerned with the production of images of the female subject that appeal to the heterosexual male spectator. ZDZ’s archive is testament to her somewhat lonely attempts to subvert the “natural” (patriarchal) rules of good photography. Her efforts did not have lasting impact in the 1960s, partly because they remained unseen and partly because they lacked a cultural and intellectual context in Soviet Latvia, but I believe that now we may be better equipped to examine and interpret her oeuvre. The story of ZDZ’s life and career also sheds light on the seemingly invisible but crushing power of the global, male-dominated photo club culture of the time. While providing a degree of equality to participants from all corners of the world, including the Soviet Union, it nevertheless rejected aesthetic sensibilities that did not aim at pleasing the heterosexual male spectator. Dzividzinska’s archive enables us to connect her work to a broader, transnational narrative of “soft” or “quiet” resistance to the oppressive authority of such spectatorship in the arts and visual culture.

- 1See Amelia Jones, Self/Image: Technology, Representation, and the Contemporary Subject (New York: Routledge, 2006).

- 2See Inga Šteimane, “Version of Time Machine,” in Black and White, by Zenta Dzividzinska (Riga: Čiris, 1999), n.p.; and Inga Šteimane, “Autobiogrāfiskā arheoloģija,” Studija 9, no. 4 (1999): 100–105.

- 3Līga Lindenbauma, “Paralēlās plūsmas 1960. – 1980. gadu Latvijas fotogrāfijā,” Foto Kvartāls, no. 6 (26) (December 2010): 8.

- 4Mark Allen Svede, “On the Verge of Snapping: Latvian Nonconformist Artists and Photography,” in Beyond Memory: Soviet Nonconformist Photography and Photo-Related Works of Art, ed. Diane Neumaier (New Brunswick, NJ, and London: Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum and Rutgers University Press, 2004), 237.

- 5Šteimane, “Version of Time Machine,” n.p.; Ieva Astahovska, “Stories about Forgetting. And Remembering,” Studija 46, no. 2 (2006): 89.

- 6See Sarah Hermanson Meister, Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography and the Foto-Cine Clube Bandeirante, 1946–1964 (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2021). See also Alise Tifentale, “Introduction to José Oiticica Filho’s ‘Setting the Record Straighter,’” ARTMargins 8, no. 2 (June 2019): 105–15, https://doi.org/10.1162/artm_a_00239.

- 7For a discussion of the significance of the photo club culture in the postwar world, especially in the regions outside North America and Western Europe, see Alise Tifentale, The “Olympiad of Photography”: FIAP and the Global Photo-Club Culture, 1950–1965 (PHD diss., Graduate Center, City University of New York, 2020), https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3537.

- 8Svede, “On the Verge of Snapping,” 237.

- 9See Pierre Bourdieu et al., Photography: A Middle-Brow Art, trans. Shaun Whiteside (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990), first published in French as Un art moyen: essai sur les usages sociaux de la photographie (Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1965).

- 10Zenta Dzividzinska, I Don’t Remember a Thing. Photographs 1964–2005 (Riga: Artists’ Union of Latvia, 2007).