Through analyses of works by David Medalla, Nick Deocampo, and Yason Banal, art historian and curator Carlos Quijon, Jr. looks beyond categorical genres of queerness, proposing instead irreducible, methodological modes that embrace its felicitous potential.

In a symposium on the history of performing arts in Southeast Asia held in Kuala Lumpur in 1997, art historian T. K. Sabapathy advocated for the embracing of “lateral methods” in art historical analyses in order to “deepen the grain of readings and interpretations.”1T. K. Sabapathy, “Retrieving Buried Voices: A Reconsideration of Premises for Writing Histories of Art of the Twentieth Century in Southeast Asia,” in Writing the Modern: Selected Texts on Art & Art History in Singapore, Malaysia & Southeast Asia, 1973–2015, eds. Ahmad Mashadi, Susie Lingham, Peter Shoppert, and Joyce Toh (Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 2018), 377. Elsewhere, literary scholar José Esteban Muñoz, elaborating the prospect of a “queer utopian hermeneutics,” wrote that “queerness’s ecstatic and horizontal temporality is a path and a movement to a greater openness to the world.”2José Esteban Muñoz, “Queerness as Horizon: Utopian Hermeneutics in the Face of Gay Pragmatism,” in Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (2009; New York: New York University Press, 2019), 68. These lines of inquiry are made to intersect in this essay and taken as provocations for a possible method of looking at an art history of queerness and, in a more expansive imagination, a queer methodology for an art history of region.

How would an art history venture into vistas of queerness without relying on the normativity of imagining a unilinear lineage of “queer art” or “queer artists,” but also without disavowing an interested, queer agency? Vital to this essay’s proposition is an errancy or, in art historian Patrick D. Flores’s conceptualization of the region, an excitation: a way of rendering vulnerable the canonical,3Patrick D. Flores, “The Artistic Province of a Political Region,” in Ties of History,exh. cat. (Manila: National Commission for Culture and the Arts, 2019), 11. or of “animating detritus to life force.”4“Patrick D. Flores: ‘Southeast Asia must be geopolitically unburdened.’ In Conversation with Tess Maunder, Singapore, 17 January 2020,” Ocula, January 17, 2020, https://ocula.com/magazine/conversations/patrick-flores. Both “queer art history” and art history of region are allowed to play out as latitude over lineage, or animated trajectories in favor of genealogies. This way, the work of the art historical becomes tropological, which for the literary critic Srinivas Aravamudan involves an “attitudinal shift” that seizes “the hope of some advantage [of] a renewed critical purchase on . . . texts and their historical contexts.”5Srinivas Aravamudan, Tropicopolitans: Colonialism and Agency, 1688–1804 (Durham: Duke University Press, 1999), 2–3.

This queer method foregrounds a “potentiality [that] is always in the horizon and . . . never completely disappears but, instead, lingers and serves as a conduit for knowing and feeling other people.”6Muñoz, “Stages: Queers, Punks, and the Utopian Performative,” in Cruising Utopia, 190. It discerns a sociality that is formative and prone to errancy—in the sense that its constituency and its valency are not schematized—but is nonetheless ardent in its anticipations of a compelled public. I deem this sociality auspicious because it promises a future conviviality, one that plays out interventive conceptualizations of social formations and the political. It is the tropological activity that carries out this auspiciousness and makes this sociality willed by plural agencies and not mere abstraction. It is in this way that I imagine queerness: an orientation toward a horizon where sociality is errant and excited, opportune and always auspicious.

Since this queer method is an orientation, it is actively positioned. Echoing Sabapathy in his remarks about regionalist endeavors, such an orientation needs “positions of advantage.”7Sabapathy, “Thoughts on ASEAN Art,” in Writing the Modern, 237. Reckoning this pluripotent, because not predetermined, sociality is queer in as much as it unsettles normative articulations of who determines, participates in, and constitutes it. Orienting the effort to write art history in this way, then, is an agentive activity not just for the art historian, the artists, and the works of art, but also for the publics and the discursive infrastructure that they constitute in this labor. In this essay, such a reckoning is identified in the practices of David Medalla (1938-2020), Nick Deocampo (born 1959), and Yason Banal (born 1972).

This auspiciousness finds exemplary articulation in David Medalla’s A Stitch in Time (1967– ), a participatory, ongoing work that invites people to embroider or sew an object onto a length of cloth using thread that hangs above it in spools. The work takes inspiration from a serendipitous meeting between Medalla and “a handsome young man who carried a backpack to which a column of cloth was attached, like a long pillow.”8“A STITCH IN TIME,” interview with David Medalla by Adam Nankervis, Las Vegas, March 2011, originally published on Mousse 29, https://www.anothervacantspace.com/David-Medalla-A-Stitch-in-Time. Sewn to this column of cloth were knickknacks that, accumulated from the young man’s travels, included a handkerchief that Medalla had gifted to one of his lovers in 1967 and that bore the artist’s name and a message he had written to them.

I start with Medalla in order to craft an art history of queerness that eludes a self-fulfilling and unilinear unravelling. Whereas typical accounts of lineage or genealogy tend to discern practices as palpably continuous, a lateral or latitudinal approach foregrounds tractions and trajectories. The momentum of A Stitch in Time is driven by a thriving traffic of individuals, objects, affects, desires. Art historian Eva Bentcheva argues that the work “function[s] not only as an abstract ‘relational’ gesture, but also as a discursive site of political and critical production.”9Eva Bentcheva, “Conceptualism-Scepticism and Creative Cross-Pollinations in the Work of David Medalla,” in Conceptualism — Intersectional Readings, International Framings: Situating “Black Artists & Modernism” in Europe (Eindhoven: Van Abbe Museum, 2019), 139. Just the same, this relationality is never abstract in Medalla’s work: fabric transforms into a matrix of agencies and affects of prolific potential activated by the participants’ encounter with the work. This is an inchoateness that rethinks the artistic object’s autonomy and suspends the usual binaries ascribed to public and private spaces. As Medalla explained in 2013: “The thing I like best about this work is that whenever anyone is involved in the act of stitching, he or she is inside his or her own private space, even though the act of stitching might occur in a public place.”10Interview with Medalla by Nankervis.

This prolific potential also plays out feminist and trans prospects. Artist Sonia Boyce, for example, intimates a feminist possibility in the continuity between “women’s work” and Medalla’s artwork that is marked by “a single material gesture, where the embroidered handkerchief stands in for the symbolic connective tissue of a sprawling network across space and time, and an uncanny loop of intimacy and estrangement . . . an expression of tenderness and care . . . passed between transitory figures.”11Sonia Boyce, “Dearly Beloved: Transitory Relations and the Queering of ‘Women’s Work’ in David Medalla’s A Stitch in Time (1967–72),” in Conceptualism – Intersectional Readings, International Framings, 143. Theorist Jaya Jacobo, in a conversation with Flores, identifies a prefiguration of a “trans potential” in the work’s “relay of women-gay-queer” that is intensified by its “transmasculine” redeployment of “feminist impulses”: “The normative and recuperated valence of the craft of woman is released, not colonized, by a gay person and his lovers. . . . The needlework must be engendered so that a binary is foregrounded and put under erasure. The ground of the needlework, which is the handkerchief, is to be marked as feminine and queer, or as the queerly feminine, because it becomes in the course of the exchange ‘transmasculine’ in its ‘intersexual’ transfigurations of ‘self, other, lover, beloved, melancholy, jouissance.’”12Patrick D. Flores, “Threading the Movement,” in Spectrosynthesis II: Exposure of Tolerance: LGBTQ in Southeast Asia, exh. cat. (Bangkok: Bangkok Art and Culture Center and Sunpride Foundation, 2019), 206.

The critical trajectory of Medalla’s work elaborates the initial moment of this essay’s reconsideration of sociality. What itineraries may be gleaned from a queer method of laterality? Perhaps to think about an art history of queerness necessitates a rethinking of how inchoate agencies take form without a predetermined teleological agenda of identity or universality, or even fetishized locality. This is perhaps where a queer methodology of region comes in: Medalla’s practice—as well as the tenor of A Stitch in Time—stakes a specificity at the same time it aspires for universal annotation. This is a poetic gesture, open to agentive intervention. In its iteration in Documenta 5, for example, the work formed part of the “People’s Participation Pavilion,” designed as an open space that “hosted gatherings, discussions, and temporary interventions” that “channeled the artists’ political statements.”13Bentcheva, “Conceptualism-Scepticism,” 275. This does not comprise a radical act inasmuch as it is a compelling sociality that is poetic, fictive, and motivated by, in Medalla’s words, “cosmic propulsions.”14Interview with Medalla by Nankervis.

In delineating a latitude of a sociality that is errant and auspicious, queerness generates a context for practice and, in turn, unsettles and reformulates hegemonic discursive formations of political and social domains.15Flores argues that the exhibitionary form has the capacity to engender “sensible socialities.” These socialities allow art and curation to generate their own contexts and thereby “enable the social practice of art to be a communicative event.” In my corollary formulation, I explore how this capacity may also present itself in general articulations of sociality that lie outside the exhibitionary context. See Patrick D. Flores, Past Peripheral: Curation in Southeast Asia (Singapore: NUS Museum, 2008) for the discussion of the exhibition form as spaces of “sensible socialities.” In the work of Nick Deocampo, such agentive and poetic impulses trouble the democratic constituency of the nation by granting queer figures a subjectivity that allows them to participate in its imagination. Deocampo’s documentary Revolutions Happen Like Refrains in a Song (1987) spans his childhood, beginning twenty years before President Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law and ending a year after he was unseated in 1986 via the EDSA Revolution, a Catholic Church–endorsed, military-backed, and urban middle-class-led uprising. The work comprises home videos, childhood photographs, and Deocampo’s footage from both the uprising and his early works. The footage of the uprising is in medias res, characterized by erratic camera movements, frantic zooming in and out, and sequences shot from awkward angles—from afar, from behind wire fences, through window slits, of the sky as helicopters hover above the protesters.

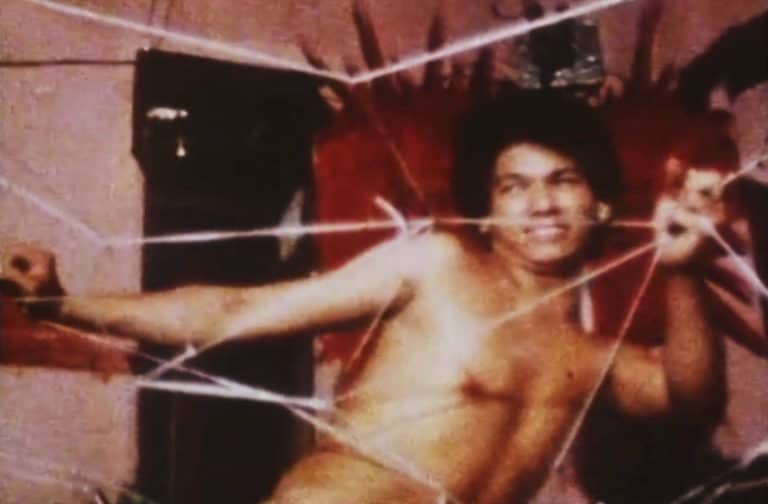

Key to Revolutions is the question of who gets to participate in the national democratic narrative. Here, this history is mediated by an openly gay filmmaker whose homosexuality becomes his “awareness . . . manner of perception . . . sensibility” and “a form of consciousness.” The work annotates democratic aspiration as it plays out in the uprising, and it is filtered through Deocampo’s cinema verité and his subjectivity, now imbued with the burden of national history. He nominates Oliver, a twenty-four-year-old gay impersonator and performer in the night clubs of Manila and the subject of an eponymous work in 1983, as a figure central in troubling the allegorical conditions of national democracy. Deocampo follows Oliver’s daily routine, interviews people close to him, and shows him performing in the clubs—in one performance, Oliver is Liza Minelli decked in gold, and in another he is butt naked, pulling a thread out of his ass. Deocampo frames Oliver’s story as the story of people outside the canonical narrative of the demos. Oliver becomes an oracle of the precarity of Manila nightlife and represents a facet of the Philippine nation that deserves further attention. In another work, one titled Mga Anak ng Lansangan (Children of the Regime; 1985), Deocampo narrates the stories of those children born under martial law who resorted to prostitution in order to survive. Queer figures such as Oliver and the child sex workers populate the world of Deocampo’s documentaries. In having them appear, speak to, and participate in the narration of national democracy, Deocampo’s work articulates a desire for solidarity, and it prospects a universality that troubles heteronormative constitutions of the demos. As Deocampo narrates: “Oliver was no isolated particular. He did not exist in a space in a life all on his own. It mattered that he existed among us.” In such a trajectory, the historical and the national are troubled, their discourses yielding to anticipatory socialities. Exposed to an errant universality, conventional ideations of nation and democracy are opened to a vaster latitude of identifications, affinities, and co-authorship, offering a reconfiguration of the democratic’s agents and address. Oliver and Deocampo’s encounter fulfills sociality’s auspiciousness, allowing a queer historical agency to play out and proffering a revision of the largely heteronormative narrative of EDSA.

This auspicious sociality reconfigures the art institutional in Yason Banal’s Third Space (Art Lab), an alternative art space he founded in January 1998 in Quezon City, Manila. It is an artist’s home that is also “a laboratory for emergent and vanguard talents who are not yet established or are not embraced by the mainstream, or those who have found success commercially but wish to experiment in other directions. It is an independent unit living on a guerilla existence.”16Yason Banal, “Third Space: About the space,” http://community.fortunecity.ws/business/breifcase/1457/about.htm. The space was funded with a grant from a “loose group of art patrons” and served as a “time- and site-specific performative installation.”17Alya B. Honasan, “A Space of His Own,” Sunday Inquirer Magazine (Makati), June 6, 1999, http://community.fortunecity.ws/business/breifcase/1457/honasan.htm.

Within Third Space’s predetermined life-span of three years (1998–2000), Banal organized a number of exhibitions, events, and performances that happened within and outside the space. For Queenly Matter (1999), for example, he invited women from different creative disciplines to walk from a shopping mall to the Space, bringing to mind the Santacruzan, a parade of women bedecked in extravagant ensembles as part of religious festivities.18In his book Global Divas: Filipino Gay Men in the Diaspora (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), social anthropologist Martin F. Manalansan IV presents an account of how the practice of Santacruzan has been opened up by the diasporic Filipino gay communities in the US. The women carried with them bags filled with whatever they deemed necessary for their trek and were asked to photograph onlookers. The photographs and bags were exhibited afterward in Third Space. For Banal, “Unlike the Santacruzan which imposes linearity (orderly procession), passivity (on the part of the mechanical muses), and exhibitionism (through a self-conscious display of beauty), Queenly Matter focuses on each artist’s journey, meaning [they] can choose wherever [they] want to go and do whatever seems worthwhile of the concept and image,”19Quoted in Honasan, “A Space of His Own.” which is “manifested through public interaction and spatial travel on the road and inside the mall.”20Email conversation with Yason Banal, August 19, 2020. In Kaka- (1999), another notable project, Banal transformed the washrooms of the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP) into temporary exhibition spaces during the presentation of the prestigious Thirteen Artists grant, a national award established by inaugural CCP curator Roberto Chabet in 1970 that has since become an index of success for its young recipients.21See Ana P. Labrador, “Art in Public and Semi-Private Spaces,” ArtAsiaPacific Magazine (October 1999), http://community.fortunecity.ws/business/breifcase/1457/labrador.htm.

Though it productively coexisted with other alternative art spaces active in the 1990s, what distinguishes Banal’s Third Space was that it did not emerge from a prior artist-run collective (e.g., surrounded by water), nor was it an expansion of a gallery (e.g, Big Sky Mind). Banal considers Third Space as first and foremost a house, and thus has kept it accommodating to practitioners of different disciplines and backgrounds.22Troy B., “Jason’s Lyric,” Philippine Daily Inquirer (Makati), July 23, 1998, http://community.fortunecity.ws/business/breifcase/1457/troy.htm. As distinctions between institutional, commercial, and alternative practices simultaneously deepened and blurred in the 1990s, Third Space created a program that “encouraged commercial artists.”23Ibid.

We discern, in Banal’s two projects mentioned above, an erratic sociality. Queenly Matter facilitated the multiple interfacings of publics, intimating various levels of engagement—from mall-goers to the parade’s onlookers and those who spoke to the participants. The mobility of the performance stitches together various modes of engagement and publicness. Kaka- inaugurates the private spaces of the washrooms as places of exhibition—intervening in the institutional social configuration by convening agents, objects, and situations. In these projects, an institution is shaped by an actual infrastructure as well as by its tropological imaginations. The auspicious sociality constituted by these venues refracts imaginations of institution, publics, and participation.

These works by Medalla, Deocampo, and Banal present exceptional understandings of how sociality becomes errant and auspicious through the experience of “knowing and feeling for other people.” The cases discussed intimate the potential of rethinking an art history of queerness that, in this felicitous imagination, finds a much riskier and more promiscuous framework that grants these practices traction on their own terms, toward more encompassing and creative socialities. This emphasis marks queerness as formative and instituent, as that which excites value and transforms it into vectors of participation in the performative facture of the art object, the writing of history, and the formation of its constituencies. In this schema, queerness is inclined to socialize and craft its public. There is no foreclosure of potentiality. Instead, there are opportunities to come together and trouble prior understandings of sociality. This essay provides an ardent reading of art history, a decision, as queer theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick puts it, to “trust in [texts or images] to remain powerful, refractory, and exemplary.”24Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, “Queer and Now,” in Tendencies (London: Routledge, 1994), 4. These three cases bring to a reconsideration of an art history of queerness, and a queer methodology for an art history of region, tendentious trajectories of gathering and assembling encumbered by political valences of sensible socialities.

- 1T. K. Sabapathy, “Retrieving Buried Voices: A Reconsideration of Premises for Writing Histories of Art of the Twentieth Century in Southeast Asia,” in Writing the Modern: Selected Texts on Art & Art History in Singapore, Malaysia & Southeast Asia, 1973–2015, eds. Ahmad Mashadi, Susie Lingham, Peter Shoppert, and Joyce Toh (Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 2018), 377.

- 2José Esteban Muñoz, “Queerness as Horizon: Utopian Hermeneutics in the Face of Gay Pragmatism,” in Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (2009; New York: New York University Press, 2019), 68.

- 3Patrick D. Flores, “The Artistic Province of a Political Region,” in Ties of History,exh. cat. (Manila: National Commission for Culture and the Arts, 2019), 11.

- 4“Patrick D. Flores: ‘Southeast Asia must be geopolitically unburdened.’ In Conversation with Tess Maunder, Singapore, 17 January 2020,” Ocula, January 17, 2020, https://ocula.com/magazine/conversations/patrick-flores.

- 5Srinivas Aravamudan, Tropicopolitans: Colonialism and Agency, 1688–1804 (Durham: Duke University Press, 1999), 2–3.

- 6Muñoz, “Stages: Queers, Punks, and the Utopian Performative,” in Cruising Utopia, 190.

- 7Sabapathy, “Thoughts on ASEAN Art,” in Writing the Modern, 237.

- 8“A STITCH IN TIME,” interview with David Medalla by Adam Nankervis, Las Vegas, March 2011, originally published on Mousse 29, https://www.anothervacantspace.com/David-Medalla-A-Stitch-in-Time.

- 9Eva Bentcheva, “Conceptualism-Scepticism and Creative Cross-Pollinations in the Work of David Medalla,” in Conceptualism — Intersectional Readings, International Framings: Situating “Black Artists & Modernism” in Europe (Eindhoven: Van Abbe Museum, 2019), 139.

- 10Interview with Medalla by Nankervis.

- 11Sonia Boyce, “Dearly Beloved: Transitory Relations and the Queering of ‘Women’s Work’ in David Medalla’s A Stitch in Time (1967–72),” in Conceptualism – Intersectional Readings, International Framings, 143.

- 12Patrick D. Flores, “Threading the Movement,” in Spectrosynthesis II: Exposure of Tolerance: LGBTQ in Southeast Asia, exh. cat. (Bangkok: Bangkok Art and Culture Center and Sunpride Foundation, 2019), 206.

- 13Bentcheva, “Conceptualism-Scepticism,” 275.

- 14Interview with Medalla by Nankervis.

- 15Flores argues that the exhibitionary form has the capacity to engender “sensible socialities.” These socialities allow art and curation to generate their own contexts and thereby “enable the social practice of art to be a communicative event.” In my corollary formulation, I explore how this capacity may also present itself in general articulations of sociality that lie outside the exhibitionary context. See Patrick D. Flores, Past Peripheral: Curation in Southeast Asia (Singapore: NUS Museum, 2008) for the discussion of the exhibition form as spaces of “sensible socialities.”

- 16Yason Banal, “Third Space: About the space,” http://community.fortunecity.ws/business/breifcase/1457/about.htm.

- 17Alya B. Honasan, “A Space of His Own,” Sunday Inquirer Magazine (Makati), June 6, 1999, http://community.fortunecity.ws/business/breifcase/1457/honasan.htm.

- 18In his book Global Divas: Filipino Gay Men in the Diaspora (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), social anthropologist Martin F. Manalansan IV presents an account of how the practice of Santacruzan has been opened up by the diasporic Filipino gay communities in the US.

- 19Quoted in Honasan, “A Space of His Own.”

- 20Email conversation with Yason Banal, August 19, 2020.

- 21See Ana P. Labrador, “Art in Public and Semi-Private Spaces,” ArtAsiaPacific Magazine (October 1999), http://community.fortunecity.ws/business/breifcase/1457/labrador.htm.

- 22Troy B., “Jason’s Lyric,” Philippine Daily Inquirer (Makati), July 23, 1998, http://community.fortunecity.ws/business/breifcase/1457/troy.htm.

- 23Ibid.

- 24Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, “Queer and Now,” in Tendencies (London: Routledge, 1994), 4.