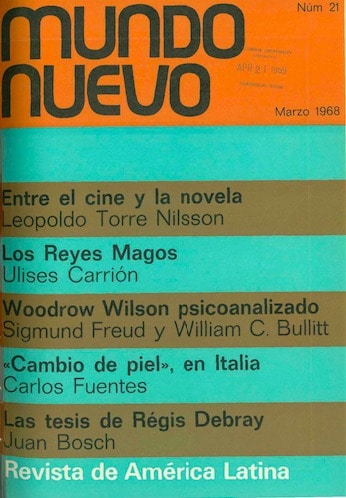

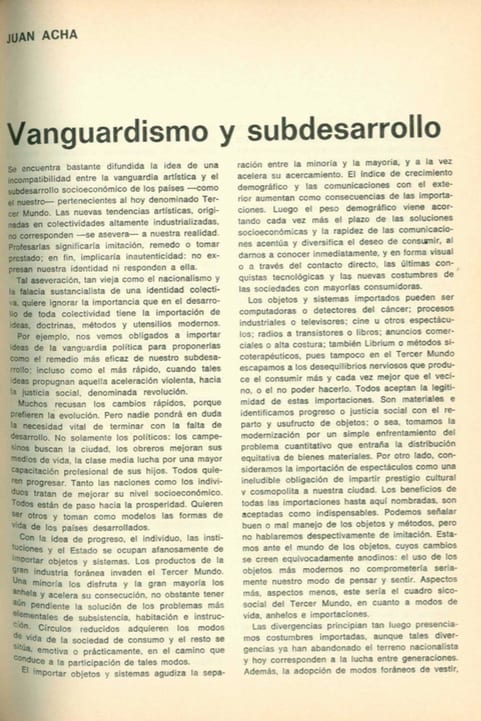

In 1968, critic and theorist Juan Acha published the text “Vanguardia y subdesarrollo.” The critical essay is available here in the original Spanish as well as translated into English for the first time.

This text was part of the theme “Conceiving a Theory for Latin America: Juan Acha’s Criticism.” developed in 2016 by Zanna Gilbert. The original content items are listed here.

English

There is a widespread notion that the artistic avant-garde is incompatible with the socioeconomic underdevelopment of countries that, like our own, belong to the so-called Third World. According to this view, new artistic trends originating in highly industrialized communities do not correspond to our reality. Following them would imply imitation, appropriation, or copying. Ultimately, it would mean inauthenticity, for they neither express nor reflect our identity.

This assertion—which is as old as nationalism and the substantialist fallacy of a collective identity—ignores the importance of the importation of modern tools, methods, doctrines, and ideas to the development of any community. We are forced, for example, to import ideas from the political vanguard and to uphold them as the most effective and even quickest solution to our underdevelopment, even though these ideas advocate the violent acceleration toward social justice known as revolution.

Many reject these rapid changes in favor of evolution. But nobody calls into question the vital need to end the lack of development. Not only politicians but also farmers turn to the city, laborers improve their means of livelihood, the middle class fights for better professional training for its children. Everybody wants to move forward. Both nations and individuals endeavor to improve their socioeconomic status. Everybody is en route to prosperity. They want to be other than they are, and so they take up, as their model, the way of life of more developed countries.

With progress in mind, individuals, institutions, and the state eagerly attend to the importation of objects and systems. The commodities of big foreign industry flood the Third World. These products are enjoyed by a minority and desired by the great majority, who rush to attain them in spite of having yet to resolve their own basic subsistence, housing, and education problems. Small circles adopt the lifestyle of consumer society, and everybody else emotionally, if not practically, embarks down the path that will enable them to do the same.

The importation of objects and systems widens the gap between the minority and the majority while simultaneously accelerating their convergence. Demographic growth rate and external communications increase as a result of imports. Demographic pressure increasingly shortens the time frame for socioeconomic solutions, while the speed of communication heightens the desire to consume, by instantly introducing us—visually or through direct contact—to the latest technological advances and newest habits of predominantly consumer societies.

Imported objects and systems may be computers or cancer detectors, industrial processes or TV sets, films or other forms of entertainment, transistor radios or books, commercial ads or haute couture. Or they may be Librium or psychotherapeutic methods, because we in the Third World are not exempt from the nervous disorders arising from the desire to consume more and always better than our neighbors—or from our failure to do so. Everybody accepts the legitimacy of these imports. They are material goods, and we equate progress and social justice with their circulation and enjoyment. In other words, we see modernization as simply addressing the quantitative problem of the equitable distribution of material goods. At the same time, we see the importation of entertainment as an inescapable obligation to bestow cultural and cosmopolitan prestige on our city. The benefits of the imports mentioned so far are accepted as indispensable. We may deem that the objects or methods in question are managed well or badly, but we will not speak disparagingly of them as imitations. It is the world of objects, in which changes are wrongly considered anodyne: supposedly, the use of the most modern objects would not seriously compromise our way of thinking and feeling. Give or take some aspects, this would be the psychosocial framework of the Third World with regard to lifestyles, desires, and imports.

The disparities arise when we are confronted with imported customs, which having left the nationalist arena, now concern the struggle between generations. In any case, the adoption of foreign ways of dressing, dancing, drinking and eating certain products, and of individual behavior are considered an inevitable consequence of global progress or communication.

The debate is exacerbated when it comes to imported forms of artistic expression. Both advocates of revolution and evolutionists protest against the presence of the international artistic avant-garde in our countries. They reproach imitation, even though it is inherent to humans and the main engine of development. Above all, they criticize inauthenticity. Why?

Because they unquestioningly believe in the existence of a fully fledged national identity, and they demand that artists take it into account—or bear in mind the basic problems of the majority at all times. Though they give free reign to the imports of physicists, technicians, or industrialists, they insist that artists confine themselves to inherited, traditional forms, disregarding the fact that these too were imported long time ago, albeit belatedly. Thus, they turn art into a real problem—the problem of whether or not it reflects the national reality or collective identity, which the individual defines dogmatically, usually based on a mindset rooted in the defense of the underdeveloped social system that is precisely what all of us want to overcome. Those with a romantic as opposed to nationalist bent call on artists to create works that are highly original or of great international significance. They consider artists to be like demiurges who create through “spontaneous generation,” without need of a favorable socioeconomic structure. Physicists and technicians, however, are not expected to make discoveries or come up with inventions, but instead to simply implement imports and manage them appropriately. Why are artistic imports censored, while the technological and/or scientific ones are not?

It is undoubtedly a matter of mindset or, strictly speaking, of ideologies. We want quantitative progress; we want the majority to participate in consumption. We resist any change in thinking beyond that required to use, handle, adopt, or imitate imported modern scientific and technological objects and systems.

We reject the need to make other qualitative or psychological adjustments beyond the generational and acculturational changes that are gradually leading us from a chiefly magical-feudal state (underdevelopment) to the mass consumer culture of industrialized societies. In other words, we do not accept the changes in thinking required for the good management of our current process of industrialization or progress. We settle for the superficial changes resulting from abusive consumption, the sinister cause of the so-called consumer society—or we prefer to live in the modern way and yet still think in the old way. This resistance to change weakens our cultural-creative force. Though all communities must go through a period focused on proper use of new imports, the psychological impact of the change their use represents must also be considered. It is essential to gradually embrace the psychological shifts required by technological invention, scientific discovery, intellectual hypothesis, and artistic creation, which are the true components of culture.

It would be pointless to inquire about the opinions of “indigenists,” whose contemptuous romantic anti-machinism leads them to believe that development is possible without abandoning the magical-feudal traditions and habits of mind that they consider to be the constituent elements of national identity. It would be similarly futile to examine the arguments of xenophobes, whose desire is to preserve traditions and keep mindsets intact, even at the expense of material progress, and of the immediate technological solutions required by population growth in the Third World today. We are instead interested in the possible behavior of our artists.

Until recently, the only option available to artists with a social conscience was to take part in the political revolution or, at the very least, to devote their efforts to the acculturation of the vast majority. There was no room for art or other spiritual expressions; these were considered premature expressions, whose true function would only begin once social justice had materialized—that is, once the basic needs of the majority had been met and this majority had been assimilated into cultural life. The national identity or reality was equated with the customs and mindset of the majority, as is typical of the magical-feudal state, which, as it happens, is in the process of disappearing.

Now a new possibility has been identified. Some artists and intellectuals refuse to devote their time and energy to integrating the majority into a system that they themselves reject. Instead, they feel obliged to caution against the errors of mass consumption and to instead provoke effects that are denounced or resisted by avant-garde trends practiced by artists in industrialized countries. In other words, they propose a cultural revolution. So, in the event of this true revolution—which is not simply about seizing power, or the socialist distribution of consumer goods, but is also more psychological in nature—ground-breaking artists would be as essential as propagators of cutting-edge political ideas or as armed guerrilla fighters are to advocates of violent revolution. Our national reality would thus become a dynamic concept reflecting a shift: the transition from the magical-feudal state that we wish to abandon to the consumer society that we aspire to. This is only right, given “the principle of reality” of the majority’s focus on mass consumption, present or future. Paradoxically, the psychological state of the majority allows us to identify the characteristics of the consumer society as the prevailing elements of our collective reality in the process of this change. That said, the political differences between the capitalist and communist methods, insofar as production and distribution go, do not matter, because today the substantial problems of mass consumption are the same everywhere.

By denouncing the errors of consumer society and suggesting certain rectifications through avant-garde practices, our artists would be taking a Third World reality as their point of departure, preventing past mistakes and promoting greater participation in technological advances. It is ultimately about the vanguard, about moving forward. In this case, collective identity would become the future result of development, or of the integration of the majority into consumption. Furthermore, just like the dominant class, which modernizes its methods by means of imports, artists will work toward achieving proposals that are truly effective for breaking away from the reality established by that class, and to counteract its modern methods of oppression and defense. Traditional artistic expressions would simply reinforce the psychological framework that the dominant class—by means of self-defense—inculcates in us.

In paternalist Third World communities, we usually find a demagogic taboo on using terms such as “consumption” and “masses.” We have been demanding the fair distribution of assets for so long that we find criticism of consumer culture disconcerting. Our quantitative concerns prevent us from seeing the qualitative aspects of so-called mass consumption, which is simply a stereotyped, prescriptive (mass) way of using material and spiritual assets to the detriment of individual freedom and imagination. It is the opposite of the cultural ideal: to generalize the individual use of cultural objects. Similarly, masses is a qualitative term, for it refers to the general frame of mind that—hiding anonymously behind the majority—demands that cultural works be accessible to common sense, to the mental framework that society inculcates in us so as to make us reject the radical changes of culture. They expect to learn to use art like one learns to use a refrigerator, by simply reading the instruction manual. Moreover, the majority that possesses the right to make political decisions—not necessarily based on reason (Nazism)—is and will continue to be against the artistic avant-garde. For as long as the majority remains blinded by the repressive and “massifying” indoctrination imposed by the state, and the problems of subsistence and pragmatic success continue to absorb people’s time and energy; for as long as the evolution of art continues to subvert the mental frameworks inculcated by those in power, and the work of art continues to spring from the rebellious fantasy of the individual; for as long as all of this continues, aversion and isolation will be the lot of the artistic avant-garde.

The big picture of the situation in the Third World today is clear: the majority seeks participation in a culture that is subverted by the artistic avant-garde. On the one hand, people aspire to or engage in the mass consumption of culture. On the other, young artists call for a cultural revolution that will transform the majority into individuals with a dynamic mentality, a profound sense of freedom, and a love of the imagination. In short, the presence of the avant-garde in the context of underdevelopment is not just legitimate, it is indispensable.

Of course, we are referring here to the artistic avant-garde as an adopted or imitated attitude—not to the actual avant-garde, which embraces new artistic approaches or trends in response to emerging social aspects that are in turn subsequently strengthened and internationalized. And the discovery of social aspects that are susceptible to internationalization, and thus able to trigger new artistic approaches of international interest, generally occurs in cities in more industrialized countries. This is where the avant-garde is born, hand in hand with aesthetic intensity. Artists in the Third World adopt and develop the avant-garde, which can also encompass aesthetic quality. It is always possible to advance the novelty of an adopted trend, or to imbue it with aesthetic quality. The odds of achieving this will obviously be greater for artists close to where the trend first took hold. This is not due to the proximity as such, but rather to the circumstances favorable to artistic development (the number of artists, a large and interested audience, good artistic level, etc.). During times of artistic upheaval such as our own, novelty and radical change become assets. However, in Munich or Milan, for example, we will find Pop and Op art of a different nature and quality to Pop and Op art in New York and London. We are also aware of the existence of Argentinean and Venezuelan “kinetic” artists of international renown. Only new information, intellectual curiosity, and a fresh mindset will make it possible for artists from the Third World to adopt avant-garde positions from the start. If our communities remain absorbed with imitating developed societies, our artists will have little opportunity to respond to internationally advanced social situations, and to embrace new attitudes of historical-artistic importance. Similarly, it would not be feasible to advocate an art that is not connected to sociological (ahistorical or native) aspects, or to expect to live in a society untouched by development, or in which development culturally values the activity of “asocial” individuals with out-of-date perspectives. The option remaining to our artists is to adopt avant-garde development at a faster pace than that of other cultural development in the Third World.

We could say that mass consumption is the psychosocial plane on which underdevelopment, as the desire to consume, converges with the avant-garde, as rectification. If so, we believe that the mechanics of this convergence would take the form of the demographic diversity that befits any nation. We would thus confirm that the supposedly contradictory coupling of socioeconomic underdevelopment and the artistic avant-garde arises from the artificial, simplified—almost abstract—world of generalizations and definitions. Underdevelopment is a characteristic of the Third World, but it does not exclude the coexistence of groups at varying levels of development (or underdevelopment), as a result of the greater or lesser circulation of imports at different regional or national levels—or, in other words, as a result of the different communication media available to each group.

We would observe differences between the city and the country; we would find small groups displaying all the typical signs of consumer culture, alongside others with partial but acute symptoms of doing so. In other words, we are convinced that the criteria of group sociology would give us a realistic perspective, avoiding the problems arising from the nationalist generalizations that are inevitable if we study the underdevelopment–avant-garde pairing indistinctly—and from the doctrinal definitions that are part and parcel of theoretical analysis of the relationship between the individual and society. Because it would quickly become clear that, often, greater levels of underdevelopment can be equated with more mass consumption than is generally believed. For instance, we would find that low economic status in shantytowns or favelas leads to the excessive use of radio, television, and mass media.

This urban group spends more time engaged with these media than other groups. But above all, group criteria would shed light on the fairly widespread belief in a collective or national identity that supposedly determines the way we think, feel, and make culture, and that urges us to reject avant-garde artistic imports.

National interests undeniably exist, and they should prevail in socioeconomic matters. But in the shadow of these particular interests, certain ideologies promote a model of national identity that also dictates cultural matters. Instead of waiting for the resultant sum of the modernizing free behavior of different groups dedicated to culture, they seek to predetermine the addends. Constructing the model is easy, given that the creation of groups—be they by families, occupations, regions, or nations—simply requires emphasizing intragroup similarities and differences, and minimizing the reverse (intergroup similarities and differences). This path leads to the definition of national identity as fixed, innate, and ethical (homeland). National similarities do exist in the form of communities of ideas and ideals, mores and customs. But these are variable similarities that, determined by fluctuating socioeconomic circumstances, are shared by the different groups that make up a nation.

In the complex, contradictory socioeconomic reality of Third World nations, the mores and customs of the most underdeveloped group (folklore) are usually considered to be the paradigms of nationality. In Peru, for instance, the “indigenous” group is the custodian of national identity, as the supposed perpetuator of “native”— which is to say pre-Hispanic—culture. However, we are discovering that almost all elements heretofore considered native are in fact imported. In this case, the matter of the relationship between the avant-garde and underdevelopment becomes a simple opposition of Western elements: the old versus the new. But proving that native culture does not exist will not make the problem of vernacular modes and behaviors go away.

We would certainly shed light on the problem if we were to assemble groups at different levels of development and study their mutual differences, past and present. Perhaps we would find varying levels of assimilation of Western culture or a cultural mix. We know that after the coexistence of pure Spanish and pure indigenous cultures at the dawn of the colony, cultural fusion occurred and criollo culture emerged. Assimilation continued over time, at the pace that each generation and group allowed, and cultural differences appeared. The criollo culture of the seventeenth century became the indigenous culture of the eighteenth century. The indigenous culture of the nineteenth century was the criollo culture of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and so on. This realization would lead us to regard national identity as a way of absorbing Western culture, or as the result of the varying rates of assimilation among different groups. Although variable and rooted in socioeconomics, national identity would continue to exist as a modal distinction.

Once we accept the existence of national identity as a variable modal distinction —it being impossible to prove the nonexistence of national similarities—we would have to find out the extent to which it is favorable to culture or development. We could argue that the notion of national identity is only favorable if it supports the most advanced imports, irrespective of whether it opposes their assimilation. Because the crucial point for the Third World is not preserving or merely importing, but rather updating and assimilating imports and hence modernizing and activating cultural activities. Consequently, we should review the bases of the institutions dedicated to disseminating culture (cultural centers, offices of cultural affairs, cultural attachés), with an emphasis on the need to support cutting-edge imports, for information purposes, and to promote activities that generate culture. Unfortunately, reviewing the bases of these institutions would amount to destroying the system that supports them.

Until very recently, it was reasonable to claim that “artists are inspired by great works, not by nature.” Now visual artists respond directly to a highly technological visual environment. Moreover, as has rightly been argued, artists are not in true contact with their entire nation, but rather with its cities. In a city, the artist has the most technological objects within his visual field. And the artistic climate of an entire nation develops in the streets, squares, cafés and classrooms, studios and exhibitions, lectures and round tables, in response to the world of utilitarian objects. These objects and works of visual art are correlated and contrasted, like questions and responses, maladies and remedies. Visual-artistic works are also objects, and they must visually compete with utilitarian objects, and particularly with the mass information and entertainment media (TV, film, glossy magazines, etc.). In other words, the relationship between the avant-garde and underdevelopment takes on real characteristics in the city. In an urban setting, a group of artists exists alongside an interested audience that introduces local models of cultural behavior to groups beyond its own, whose cultural advancement primarily depends on the socioeconomic structure and its flexibility. This is yet another reason to adopt a group-sociology methodology to study the problem that concerns us here.

In the city—in the most populated urban centers within each country—we find the world of modern objects and of information and entertainment media, and we perceive huge gaps between artistic generations. Also, given the far-reaching changes in the world of modern objects and mass media, visual artists are forced to confront and make greater changes in their work than, for example, writers, who are engaged in the relatively unchanging affective world.

At the same time, the enormous influx of visual entertainment and information in the urban sphere widens the generation gap. For the past five years or so, young visual artists from the Third World have been working at a different pace and in a different spirit. They ignore the established values of their own environment and imitate their contemporaries at work in New York, London, or Paris. The objects and information and entertainment media that these Western artists employ from a young age arouse the modernizing desire in Third World artists. Modern objects and information are accompanied by certain practices grounded in the idea of individual freedom, advocated by the extremist tendencies in the visual arts that demand immaterial, unsellable works, and defended by those cultural guerrillas known as “hippies,” who subvert the mores and customs of consumer society through a loving, libertarian passive resistance. The paradox deepens: cultural and artistic “guerrillas,” the byproducts of highly developed societies, share the same field of underdevelopment. Better still, the “seriousness” of material development and the counterproductive “uselessness” of the artistic avant-garde have to walk hand in hand. The idea of waiting—allowing for development first, and then avant-garde incursions—would stifle art and annul the effects of the avant-garde’s denunciation and prevention of the maladies of consumer society that are upon us.

In comparing groups at different cultural levels, we will find there to be wide variation, given that the extremes in the Third World are so far apart. As such, there will be a greater diversity in terms of artistic expression and application, and of sensory balance, than elsewhere. We will find works based on rural or urban folklore, avant- garde works, and works that are suspended in the past. Each group artistically expresses itself in its own way, in keeping with its cultural norms and its concept of reality. No other time period has favored the development of human diversity as much as our own, or allowed so many cultural levels to coexist—in this case, as a consequence of the path down which the individual embarks to advance socioeconomically, and of the different possibilities for cultural ascent and communication within each region, and among different groups.

While this cultural inequality is regrettable from the point of view of social justice, the existence of a wide range of artistic expressions within a single group is not bad in itself. What is reprehensible is their hierarchization, particularly that by conservatives blocking the activities of the avant-garde. We are nevertheless used to hierarchization. So when a critic positions a work within the historical-artistic timeline or sequence, and praises its supposed alignment to a new reality, we think that he is placing contradictory or superior value on it over the work of a cubist, impressionist, or renaissance artist in his respective time.

The antiquity complex, imbued with historicism and transmuted into misoneism, and the novelty complex, overrated by mass evolutionism, are constantly pitting themselves against each other. And people choose one of the two: the value of precedence, or the value of the latest trend. Few manage to appreciate the steps taken by creators of culture as reactions to new sociological realities, and to the dispassionate desire to transform them in a progressive sense, without aspiring to objectives or to perpetuation, concepts invented by humans to establish dogmas, dictate rules, and impose a stability that make us feel safe. Those who are able to appreciate this will accept the legitimacy of the artistic expressions of different groups. Because just as each period has its own advanced art and diverse artistic considerations, so do coexisting cultural positions. It would be wrong to undervalue these expressions at the human or social level, even though it is admissible to point out their lack of topicality or to reproach those who create them for the pretensions of modernity. It would also be wrong to expect groups at a cultural level of the past to accept avant-garde works. Though the ideal would be for everybody to be at the same cultural level, human diversity is inevitable: not everybody shares the same interest in each of the arts, and in any case, different art forms prevail in each age.

The desire to eradicate hierarchization, for art to dissolve into life and for artworks to be seen as simple visual exercises with strong spectator participation, is the banner of the artistic-visual avant-garde. What would be the point of showing a Primary Structure, for example, to someone with a pre–typographic sensory frequency, a gaze unsullied by preconceptions? If education were truly functional, this fresh gaze would be good raw material for teaching Third World groups how to look at avant- garde work. But this education would fall flat among groups not yet subjected to the maladies of consumer society. The avant-garde addresses groups that dictate cultural models from an earlier cultural state. As such, artistic communication among different groups only works if it moves gradually from the latest to the oldest, or most backward. The avant-garde moves forward, but it does not gentrify. Avant-garde artists and the groups interested in their work generally value the folklore and works of the past. But the rural man is indifferent to the avant-garde, just as a group that did not move beyond a renaissance or abstract aesthetic disparages works from later movements. This will continue to be the case for as long as cultural and socioeconomic inequalities exist, and for as long as the modes of communication are not negated. In any case, an indisputable fact remains: film and TV—the arts of our time—capture the visual appetites of the majority, in spite of the cultural differences of the groups that constitute it.