In this essay, art historian Rita Eder reviews, from a personal and first-hand point of view, the breadth and impact of Juan Acha’s critical contribution to Latin American art from the 1970s to the 1990s. She locates Acha’s theory of no-objetualismo (non-objectualism) within his wider production and considers his preoccupations with materiality, artistic hierarchies and the circulation of information.

Read the essay in its original Spanish here.

This text was part of the theme “Conceiving a Theory for Latin America: Juan Acha’s Criticism.” developed in 2016 by Zanna Gilbert. The original content items are listed here.

I first met Juan Acha in August 1975. The occasion was the 1st International Colloquium on Art History, entitled “La dicotomía entre arte culto y arte popular” (The Dichotomy between High Art and Popular Art), organized by the Institute of Aesthetic Research, under its then director Jorge Alberto Manrique, in the city of Zacatecas. My confrontation with Marta Traba at this colloquium, and my painstaking preparation of a commentary on the paper presented by a formidable figure such as Marta, were maybe what earned me an invitation to participate in the symposium “The Latin American Artist and His Identity” a few months later. This second event was organized by the Peruvian critic Juan Acha and Kazuya Sakai, the Mexico-based Argentinean painter who was then directing the visual arts section of Octavio Paz’s Plural magazine (1971–76). The symposium was held in Austin, and organized in collaboration with the University of Texas, the Blanton Museum of Art, and Argentinean art historian Damián Bayón, who was teaching modern Latin American art at the university at the time. In organizing this event, Bayón, Acha, and Sakai sought to stimulate debate around art and literature in Latin America and to open up an opportunity to share information and experiences on related subjects and problems among artists and critics, art historians and writers.

A few years later, in November 1978, the 1st Bienal Latino-Americana de São Paulo was held, at the initiative of Juan Acha, who convinced the director, Aracy Amaral, to turn the event into a space for the discussion and exhibition of Latin American art.1As art historian Isobel Whitelegg notes, “…The Fundacão Bienal had, in 1978, hosted a Bienal Latino-Americana de São Paulo. That event, however, had not replaced São Paulo’s recognised international exhibition but rather the series of national biennales that had been held, since 1972, in the off-years in between… It also reactivated an earlier more radical proposal to replace the international with the continental, a plan that she had been involved in drafting in 1975.” Isobel Whitelegg (2012) “Brazil, Latin America: The World,” Third Text, 26:1, 131-140. Nonetheless, in spite of the discussions and meetings that took place in parallel to the exhibition and a year later in an attempt to legitimize its continuation, the idea of a purely Latin American biennial did not survive beyond its first edition. This defeat was primarily orchestrated by Argentinean cultural promoter and entrepreneur Jorge Glusberg and his ‘Group of 13’, which included Victor Grippo and Leopoldo Mahaler. The exhibition was accompanied by a symposium in which speakers including Nestor García Canclini, Mirko Lauer, Frederico Morais, Marta Traba, and Juan Acha himself presented what could well be considered new approaches to art in Latin America. The new points of view put forward at the event, and Juan’s contributions to the proceedings, will be discussed below. But first, to gain an insight into his Latin Americanist thought, it is worth noting another detail that has not yet been mentioned here.

Around the middle of 1977, while J. A. Manrique was still director of the Institute of Aesthetic Research, Juan would often go there to discuss editing a series of essays on Mexican geometrism. It was the decade of the renewal of Mexican art, after the disputes between the intransigent Salón de Plástica Mexicana led by Alfaro Siqueiros and the 1967 Salón Esso in which Juan García Ponce was actively involved. Around that time, a group of painters and sculptors from different generations had objected to the state-organized Salón Solar, which was supposedly meant to be the cultural showcase of the 1968 Olympic Games. In response, independent salons were set up between 1969 and 1971, displaying numerous experimental works, particularly in regard to materiality and the crystallization of geometric abstraction in the pictorial field.

In the critical reviews that Acha wrote for Plural—before the magazine’s dramatic demise in 19762In 1976, during the Luis Echeverría’s presidency, the newspaper Excelsior, then directed by prestigious journalist Julio Scherer, was shut down for political reasons in the midst of great scandal.—he argued for the need to examine Latin America’s visual culture based on its geometric, abstract intellectual roots, and defended the desire for rationality in Latin American art, perhaps as an aesthetic response to the problems of underdevelopment. Juan Acha asked: why not go beyond the espousal of political passion in art, beyond social realism and beyond the self-exoticism that some painters had turned to during the first half of the 20th century in Latin America? While Marta Traba fiercely defended modernisms in 1950s and 1960s Colombia, particularly the informalist aesthetic and moderate abstract languages, Acha called for the revitalization and recognition of this rationalist but sensitive line in Latin American art.

A few years later, in 1981, he made the big leap to no-objetualismo (non-objectualism), a concept that he introduced into the public sphere as the main organizer of a symposium and exhibition in Medellin, Colombia. As far as theory is concerned, the journey to non-objectualism began in the seventies, when Acha published several articles on the subject in Artes Visuales, a magazine directed by Carla Stellweg and published by the Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico City. Juan Acha was a special editorial consultant to the museum, and wrote many of its catalogue texts. He also published his views on contemporary art in the magazine Plural, in conjunction with Kazuya Sakai, who was the magazine’s designer.3Damián Bayón, El artista latinoamericano y su identidad, Caracas, Monte Ávila Editores, 1978. In October 1975, Damián Bayón, Juan Acha and Kazuaya Sakai organized a colloquium at the University of Texas in Austin, along with an exhibition on Latin American art focusing on geometric and informalist abstraction. Participating artists included: Colombia’s Edgar Negret and Ramírez Villamizar, Brazil’s Rubem Valentin, Argentina’s Marcelo Bonevardi, Peru’s Fernando de Szyslo, and Mexico’s Manuel Felguérez and Vicente Rojo. The book includes the papers presented at the colloquium, and a small catalogue was also published in conjunction with the exhibition. Together, they persuaded the museum to increase the number of exhibitions of Latin American artists, from the modern classics to artists working in the field of geometric abstraction. If we could say that Mexican art at one stage exported social realism, Acha and Sakai wanted to turn the map of America upside down and make geometric abstraction flow from the South towards Mexico, without undermining the theorizing and dissemination of certain forms of conceptual art and performance.

It is interesting to note that Juan Acha tried to change the accepted narrative of Latin American art by pushing social realism and fantastic realism into the background, along with connotations of irrationality, and putting the spotlight on the South American geometric tradition and his desire to build a Latin American rational and forward-looking project. This perspective helped to shape the exhibition El geometrismo mexicano (1977).

The magazine Artes Visuales fanned the debate around contemporary problems in art, which included the gender perspective, conceptual art, photography and its aesthetic redefinition, new Latin American criticism, and the birth of a new form of art in Mexico. This new approach was based on a different way of organizing in the form of artists’ collectives that sought to reformulate the meaning of political art and worked towards public art strategies, with a special interest in the cognitive process of spectators. These issues that concerned the editors of Artes Visuales were enhanced by the ideas and theoretical work that Juan Acha developed as he actively reflected on a new art for the acceleration arising from social and technological change in the 1970s.

The first article that Acha published in Artes Visuales in 1973, “Por una nueva problemática artística an Latinoamérica” (For a New Artistic Problematic in Latin America), defined the dilemma in terms of the coexistence of two different realities and sensibilities, by which he referred to the cultural confrontation between the first and the third world. Acha’s solution was based on the paradigm of Brazilian art and its anthropophagic tradition or, in other words, on the possibility of appropriating whatever is necessary without abandoning certain sensitive values. But what really concerned Acha was the pressing need for Latin American artists to get onboard with the dynamism and change that the third world required. Using language tinged with developmentalism, sometimes unnecessarily complex in his eagerness to cover all aspects of a problem in a single sentence, Acha defended international contemporary art and pointed out the weakness of Latin American artists when it came to expressing ideas and formulating theories of art. This called for autonomous visual thinking that could apprehend the visual realm as an extensive world of images, putting on the table the need to think—as the theorist of images and perception Rudolph Arnheim did—about the inseparable link between the act of thinking and the processes by which images are formed. This independent visual thinking was not formalism; it arose from immediate visual practice, with visual elements as the springboard to connect to other contemporary theories. In his approach to visuality and the interaction between art and the ideas of image and culture, Acha was among the first to understand the advent of visual studies as a way of understanding changes in perception and in artistic genres themselves. Acha looked to the future, worried by what he considered to be the blindness of subjectivism and nationalism, and warned of the unstoppable advent of the industrial age and mass culture, which interpenetrated borders, heedless of illiteracy and feudal remnants.

Juan Acha presented himself as a theorist of contemporary art and of the Latin American condition. Like the Brazilian poet and critic Ferreira Gullar, he sought to promote the notion of the legitimacy of the avant-garde in situations of underdevelopment,4Juan Acha, “Vanguardismo y subdesarrollo,” in Ensayos y ponencias latinoamericanistas, Caracas, Galería de Arte Nacional, 1984, pp. 11-27. “Vanguardismo y subdesarrollo” was first published in the magazine América Latina, Paris, September-October 1970, vols. 51 and 52. questioning whether this avant-garde would necessarily have to be a native one. Rather than evolution, he believed in change and in the impact of art on underdevelopment. In his opinion, Latin America was made up of various groups that lived in different times. He thought that isolation and identity based on an ancestral substratum or on a national essence were no longer an option in light of the new technologies, computing, and mass media that had brought about a rupture in art. The art world was moving into new, more dynamic times, driven by what the Peruvian critic called the extremist tendencies of the visual arts, which called for the immaterial, unsalable works proposed by cultural guerrillas. He sought to draw attention to the de-hierarchization of the arts, the strong spectator participation, and the transformation of third world societies, in response to which artists should replace self-concern with a freer practice, ready to participate in the feast of the art world and take part in what he called revolutionary progress.5Juan Acha, “Por una nueva política artística en Latinoamérica,” op.cit., p. 27, first published in Diario Nueva Crónica, Lima, 10 and 11 April, 1972. This artistic strategy encompassed the utopias of those years in which artistic education had to change tack in order to prepare the artists of tomorrow. Acha thought in total terms, and his acuity in perceiving the different interacting factors was at odds with the impossibility of directly transmitting his ideas in highly complex sentences strung together as unbroken text without subheadings or quotes. This difficulty was also largely due to a particular take on dialectics, in which each sentence contradicts itself and is enhanced by the meeting of opposites; although this is a valid method, Juan took it to the extreme and may at times have prevented a deeper engagement with his theoretical dilemmas. His efforts as a critic were subsumed into his broader efforts in the field of theory, and this made him a strong influence on visual arts students at the Academy of San Carlos. In retrospect, his theoretical work can be considered representative of certain approaches that tried to formulate a Latin American definition of Conceptual Art, which he conceived as non-objectual art, culminating in a major Latin American exhibition in Medellin, Colombia, in 1981, which revolved around this theme.

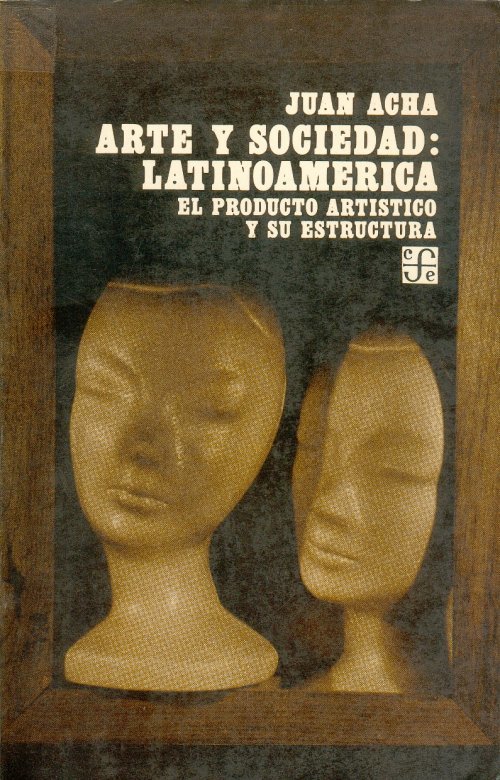

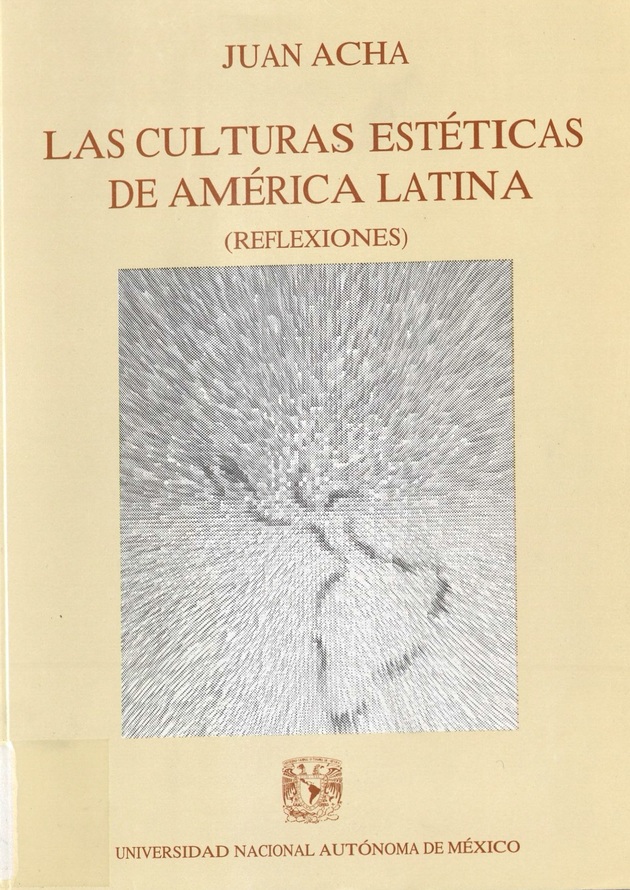

Now that I’ve gone back and taken a fresh look at his texts with an open mind, I’ve been wondering about Juan’s legacy in regard to theoretical thought on modern and contemporary art in Latin America. I think that part of the answer can be found in his book Arte y Sociedad: Latinoamérica (Art and Society: Latin America), a thick volume of over 500 pages published by Fondo de Cultura Económica in 1979, and in Las culturas estéticas de América Latina (Aesthetic Cultures of Latin America), which was published by the UNAM almost fifteen years later.

The first of these books introduced the notion of art beyond its objectuality and its confinement to the art world. The main idea was to think about art as a system of relations, in which the object is only one of the elements of a broader system that takes into account reception and the market, and in which there is room to study the conditions of production of the object, which could become a commentary on the object itself. In other words, an appeal to the conception of a different kind of materiality that breaks away from the idea of the artist as a producer of works. Acha saw this as just the start of a broader vision in which art became one with design and popular arts. He generalized, eager to transmit the diversity and multiplicity of meanings of a single object, idea, or creation, and he went out of his way to connect scientific and artistic topics through technology and its impact on culture.

Latin American reflection on the arts, Acha argued, was bogged down in an art of resistance, as Marta Traba would have it, or in the syntheses and compendiums of Latin American art, as Báyon suggested. Acha believed that the discussion would only move forward if it was backed by theoretical reflection. We could say that these efforts permeated by new means of approaching art were already underway. Social sciences as practiced in Latin America had already affected the notion of culture. I am thinking of García Canclini and Mirko Lauer, who were a starting point for Juan, although he discreetly—perhaps overly so—refrained from ever, or almost ever, naming them. He debated with them and tried to make his mark by means of contemplating something that he thought was overlooked by sociological and Marxist approaches: understanding the lack of in-depth reflection on the materiality and nature of art, and as such on aesthetics. In his efforts along these lines, Juan read tirelessly, connecting seemingly contradictory ideas: on one hand, materiality, production, consumption and distribution, and on the other, subjectivity and reflection on aesthetics. Acha was influenced by his sociological perspective, which noted the importance of cultural change influenced by the media and the spread of urban popular culture, and the impact of industrial design on visual culture. Each of the ideas that Juan wanted to include in his vast, rich, complex reflection was wrapped in a torrent of knowledge and reading. He believed that the artistic-visual system was constantly expanding or in flux, and that the situation called for a variety of methods of analysis—formal, semiotic, and structuralist—which helped to identify what he called “the hidden logic of structural changes.” Acha argued that this hidden logic is the ideology that mediates between the material basis of society and artistic-visual change.

One of his key questions—how is an artistic product generated?—seemed to remove him from art history, which he perhaps mistakenly conceived as a formal exercise lacking the capacity to generate social and anthropological interpretations. He moved step by step, struggling between a consecutive and a simultaneous narrative. His response included society, the individual, and the system of production, but it also considered how these processes took place in the artistic-visual changes of the last hundred years. In his diatribe against art history, he tested new classification systems, concluding that it is possible to dispense with the long list of “isms” and chronologies, and think in terms of four groups that define twentieth century avant-gardes and movements: abstraction, objective realism, non-objectualism, and conceptualism. All of these systems clash amongst each other and technology runs through them, causing the outside to enter art or, in other words, introducing distribution and consumption. So, what is this ideology that mediates between the material basis of society and artistic-visual changes? Acha’s answer suggests that it is the technocratic ideology that changes materials and transforms human sensibility.

“Technocratic ideology does not concern Latin Americans,” he said, which is why ideological mediations are different in the case of Latin America. The underlying issue according to Acha is nationalism, “the crux that runs through all Latin American art” and has surprisingly, in the Peruvian’s critics view—led to its only major transformation: Mexican muralism. Nationality and national identification run through all of it, he argues.

In the chapter on crafts, he describes Latin America as a place where high art coexists with design and popular art, principally with the rural arts or crafts that play a key role in the transformation of urban culture, decreasing its dependence on external models. In this sense Acha supports and shares Aníbal Quijano’s disquisition, which defends a Latin American urban popular culture influenced by local traditions as an alternative to a dependent urban culture immersed in external models.

Acha warns against any glorifying essentialism in regard to crafts, and suggests looking at the phenomenon from the perspective that has become his way of understanding art: as a complex set of interrelations in constant flux. “Artistic structure is of interest to us wherever it is,” he wrote. Crafts are one of the forms of art, and perhaps they can no longer position themselves as pre-capitalist production, given that they are increasingly integrated into capitalism. Acha spoke about this with García Canclini, Mirko Lauer and Ticio Escobar, who had reflected on the subject of crafts. He tried to increase the flexibility of conclusions, affirmations, and axioms regarding them and their integration as one of the fundamental pillars of the system of the arts in Latin American cultures.

Always in dialogue with the notion of underdevelopment and the third world, he argued that the peculiarity of Latin America is the mix of different realities, and pointed out the importance of production from rural areas, and the need to create the conditions for theory and methodological analysis that can advance reflection on arts in the region.

In the introduction to Las culturas estéticas de América Latina, Acha began with a general perspective on art. In simple and direct language, he said that Latin American scholars should focus on national realities instead of insistently looking to Western aesthetics, and that they should particularly avoid considering them universal. He notes that in order to know Latin American art it is necessary to strike a balance between aesthetic knowledge of different cultures and the need to navigate using comparative tools for exploring visual cultures. It is a monumental, impossible task, but an interesting and valid one.

In Acha’s view, Latin American aesthetic culture was not just the sum of national aesthetics, but also the exchange of artistic projects, experiences, and knowledge in our countries. Aesthetic diversity was his theoretical pillar, and he certainly dismissed the notion of aesthetics as a purely Western body of thought.

Acha’s research led him to develop an idea or theoretical approach to art that would be capable of reconstituting and reformulating the notions of aesthetics and art history as practiced in Latin America. This difference may have stemmed from the definition of its overall characteristics, or recurring issues such as the link between art and religion, the problem of identity, and the ambiguous but ongoing relationship with European aesthetics and artistic movements.

Juan Acha paid homage to the grand narratives when he tried to encompass everything from the origins of American man to pre-Columbian aesthetics, the different forms of the colony, the awakening of the national consciousness, and the arts in 1990. I think that this last book, Las culturas estéticas de América Latina, completed in 1992, was his response to histories of art that tried to sum up Latin American art in the form of timelines, stylistic categories and other arguments and instruments that prevented moving forward with the debate on the characteristics of artistic-visual expressions in Latin America. This last work may be a legacy for his students and for all of us who want to think about these matters. He left us ideas, categories, points of view, and theoretical reflections to argue against. He also left us his example as a scholarly, honest man, who avoided intellectual frivolity and was committed to his profession as a researcher, teacher, theorist, and critic of art. I remember how intensely he listened and read, how much he published and how he understood the urgency of his mission: to reflect on the meaning and structure of art in modernity, and to construct an aesthetic or a philosophy of the visual arts in Latin America, a kind of general theory that would make it possible to think about Latin American art from within its own artistic systems/structures and its differences.

Conscious of the need to interconnect ambitious projects that would change the course of Latin American cultural thought, his works are a genuine contribution to that diffuse, complex, sometimes vague, but appealing—not to say fascinating and necessary—field, which is the convergence of studies of art and aesthetics from the Latin American perspective.

- 1As art historian Isobel Whitelegg notes, “…The Fundacão Bienal had, in 1978, hosted a Bienal Latino-Americana de São Paulo. That event, however, had not replaced São Paulo’s recognised international exhibition but rather the series of national biennales that had been held, since 1972, in the off-years in between… It also reactivated an earlier more radical proposal to replace the international with the continental, a plan that she had been involved in drafting in 1975.” Isobel Whitelegg (2012) “Brazil, Latin America: The World,” Third Text, 26:1, 131-140.

- 2In 1976, during the Luis Echeverría’s presidency, the newspaper Excelsior, then directed by prestigious journalist Julio Scherer, was shut down for political reasons in the midst of great scandal.

- 3Damián Bayón, El artista latinoamericano y su identidad, Caracas, Monte Ávila Editores, 1978. In October 1975, Damián Bayón, Juan Acha and Kazuaya Sakai organized a colloquium at the University of Texas in Austin, along with an exhibition on Latin American art focusing on geometric and informalist abstraction. Participating artists included: Colombia’s Edgar Negret and Ramírez Villamizar, Brazil’s Rubem Valentin, Argentina’s Marcelo Bonevardi, Peru’s Fernando de Szyslo, and Mexico’s Manuel Felguérez and Vicente Rojo. The book includes the papers presented at the colloquium, and a small catalogue was also published in conjunction with the exhibition.

- 4Juan Acha, “Vanguardismo y subdesarrollo,” in Ensayos y ponencias latinoamericanistas, Caracas, Galería de Arte Nacional, 1984, pp. 11-27. “Vanguardismo y subdesarrollo” was first published in the magazine América Latina, Paris, September-October 1970, vols. 51 and 52.

- 5Juan Acha, “Por una nueva política artística en Latinoamérica,” op.cit., p. 27, first published in Diario Nueva Crónica, Lima, 10 and 11 April, 1972.