Jean-Michel Atlan (1913–1960)—who signed simply as Atlan in his works—1Before settling on “Atlan,” he signed his works “J M Atlan” or “J M A.”is most often considered a representative of lyrical abstraction, an art movement that took root in Paris after World War II. Born in the Casbah of Constantine to a Jewish Berber family (a fact he often emphasized),2For example, see Ernest Bénézit, Dictionnaire critique et documentaire des peintres, sculpteurs, dessinateurs et graveurs [. . .], vol. 1, Aa–Beduschi, new ed. (1911; Paris: Librairie Gründ, 1999), 520–22; or Michel Ragon and André Verdet, Jean Atlan, Les Grands peintres (Geneva: René Kister, 1960), 10. his Algerian childhood lent specific forms and colors to his uniquely creative imagination. Atlan’s parents combined tradition and modernity, enrolling their children in both a Talmudic school and a French secular school. Steeped in the mystic readings of sacred texts, his father transmitted knowledge of the Kabbalah to his son, a legacy that would remain important to the artist throughout his life.

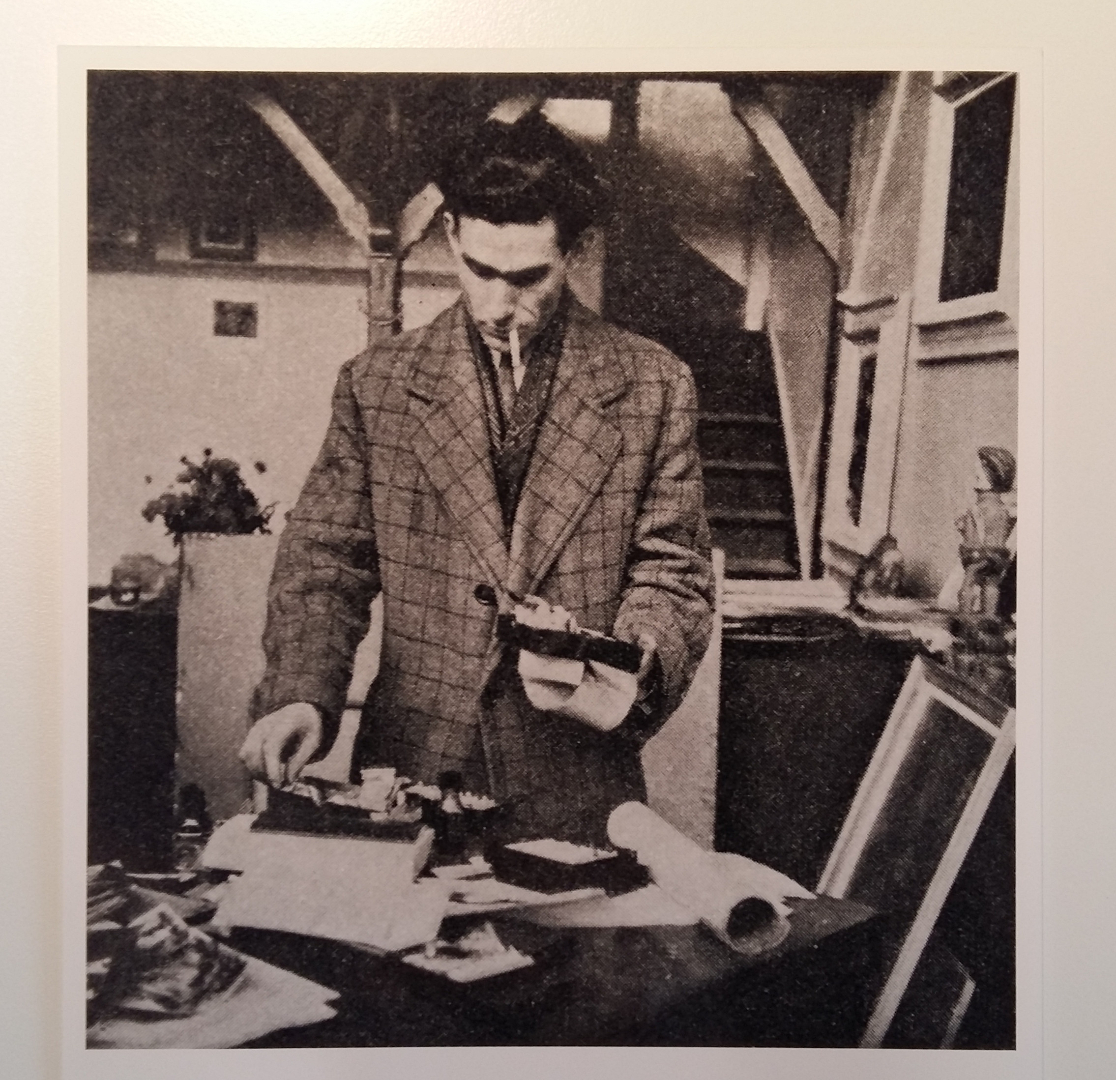

In 1930, Atlan left home to study philosophy at the Sorbonne. He became involved in political circles as soon as he arrived in Paris, publishing in Trotskyist journals like La Vérité (The Truth) and attending anti-colonial protests. Concurrently, he began writing poetry, drawing closer to the literary circle surrounding Georges Bataille (1897–1962) and the revolutionary Surrealist movement. He started teaching philosophy but was dismissed when the Vichy regime began to collaborate with Nazi Germany and implemented anti-Jewish laws. Within this extremist context, in 1940, Atlan started to make visual art. Imprisoned under the pretext of “Communist activities,”3Resistance fighter certificate from the office of the National Front for the Fight for French Liberation, Independence, and Rebirth, dated April 23, 1949. Bibliothèque Kandinsky (hereafter BK), Atlan collection, shelf ATL 70. then committed to the Sainte-Anne psychiatric hospital from January 1943 to August 1944, he executed his first paintings on boards and makeshift canvases provided by friends and hospital staff.4Letter of Atlan to Denise René, February 14, circa 1943. BK, Atlan collection, shelf ATL 85.

Once Paris was liberated, Atlan dedicated himself entirely to painting, declaring: “I’ve made the leap from poetry to painting, like a dancer who has discovered that dance is better than verbal incantations for his self-expression.”5Michel Ragon, Atlan, Collection “Le Musée de poche” (Paris: Georges Fall, 1962), 5. Unless otherwise noted, all translations by Allison M. Charette. He made his breakthrough in the art scene in December 1944, right after the war, at a time when artists had to reinvent themselves to rebuild their relationship with the public.6Atlan’s first solo exhibition opened in December 1944 at the Arc-en-Ciel Gallery on Rue de Sèvres in Paris. It was hailed by critics, and Jean Dubuffet (1901–1985) wrote to the artist to express serious interest in his distinctive work. See Dubuffet to Atlan, January 4, 1945. BK, Atlan collection, shelf ATL 83. Nonetheless, his career and distinctive work have posed a challenge to critics. Atlan was perceived both within the School of Paris and on its fringes, engaging in every pictorial trend—from “Art Informel” to lyrical abstraction—so as to better disassociate himself from all of them.7The term “Art Informel” (from the French informel, which means “unformed” or “formless”) was first used in the 1950s by French critic Michel Tapié in his book Un Art Autre (1952) to describe a nonfigurative pictorial approach to abstract painting that favors gestural and material expression.

After the war, Atlan was hailed as an innovator by new gallery owners such as Denise René and Aimé Maeght as well as by art critics and historians, including Jean Cassou, Charles Estienne, and Michel Ragon (who would become one of the artist’s closest friends). Like French writers Jean Paulhan, Jean Duvignaud, and Clara Malraux, American writer Gertrude Stein was among his first supporters, purchasing several of his works. As a philosopher, Atlan was comfortable taking stances on issues rocking the art world and in 1945, published a manifesto in the second issue of the French journal Continuity.8Jean-Michel Atlan, Continuity, no. 2 (1945): 12. In this text, he questioned the concept of reality, and, further, the conception of realism—which, according to him, resulted in paintings that were too literal.9“Can we force new forms into concrete existence? Is purely plastic expression possible? It will gradually become clear that the essential task of young painting is to replace the vision of reality with the authenticity and reality of vision.”, in ibid. Atlan felt a profound sense of freedom and broke his contract with Galerie Maeght in 1947. After making that decision, which was praised by the French artist Pierre Soulages (1919–2022),10As related to Amandine Piel by Pierre Soulages, January 14, 2019. Atlan experienced a slower period in his career. However, he continued to paint and exhibit. In 1957, his career gained momentum again with a mature body of work that received international recognition in Europe, Japan, and the United States. He would not attend the April 1960 opening of his solo exhibition at The Contemporaries Gallery in New York, because he died in Paris on February 12 in his studio on rue de la Grande Chaumière. By tracing the trajectory of his unconventional career, from his homeland to his premature passing, one can gain a deeper understanding of this self-taught artist’s distinctive impact on art, transcending predefined categories and movements.

A Gestural Painting Focused on the Sign

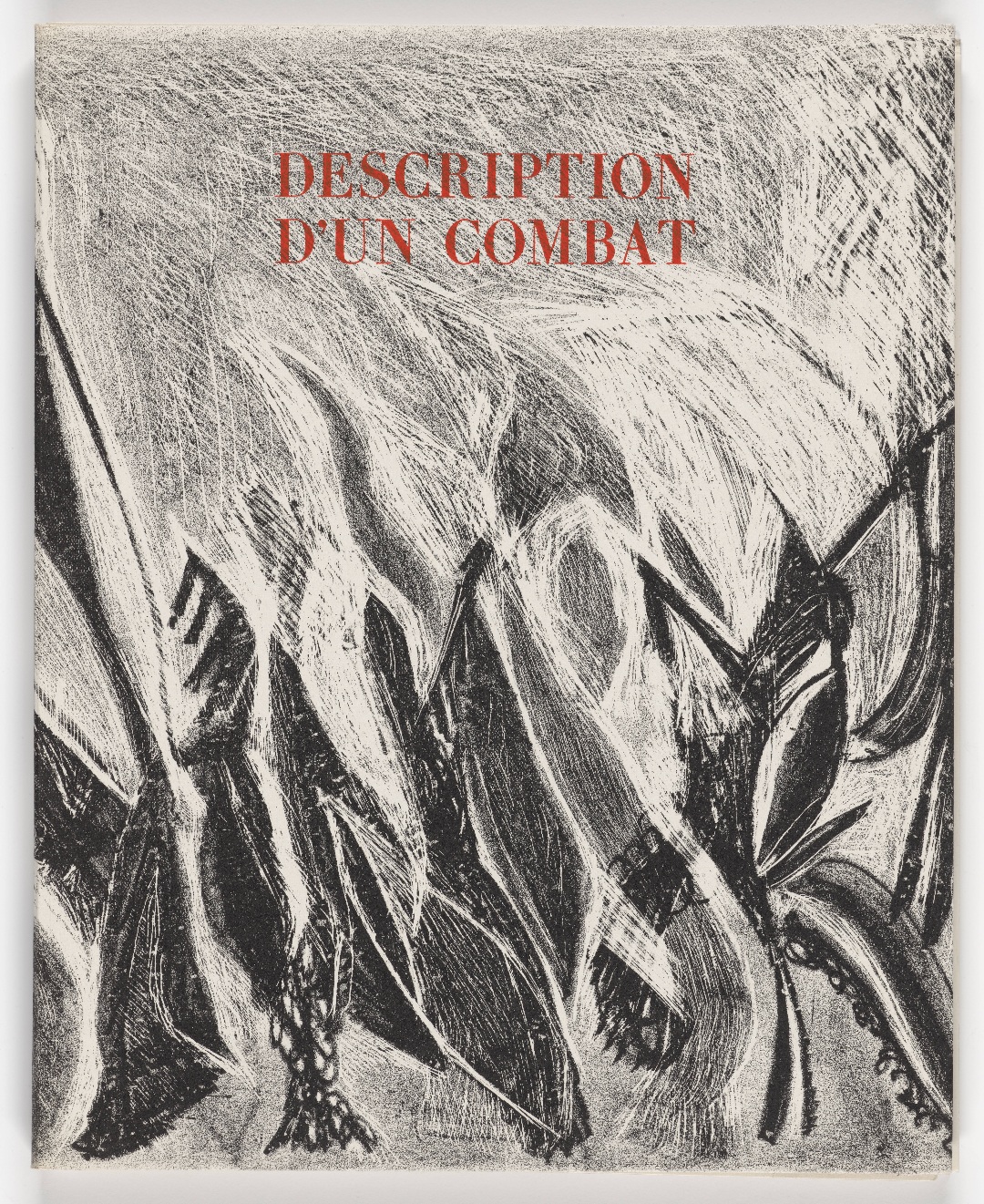

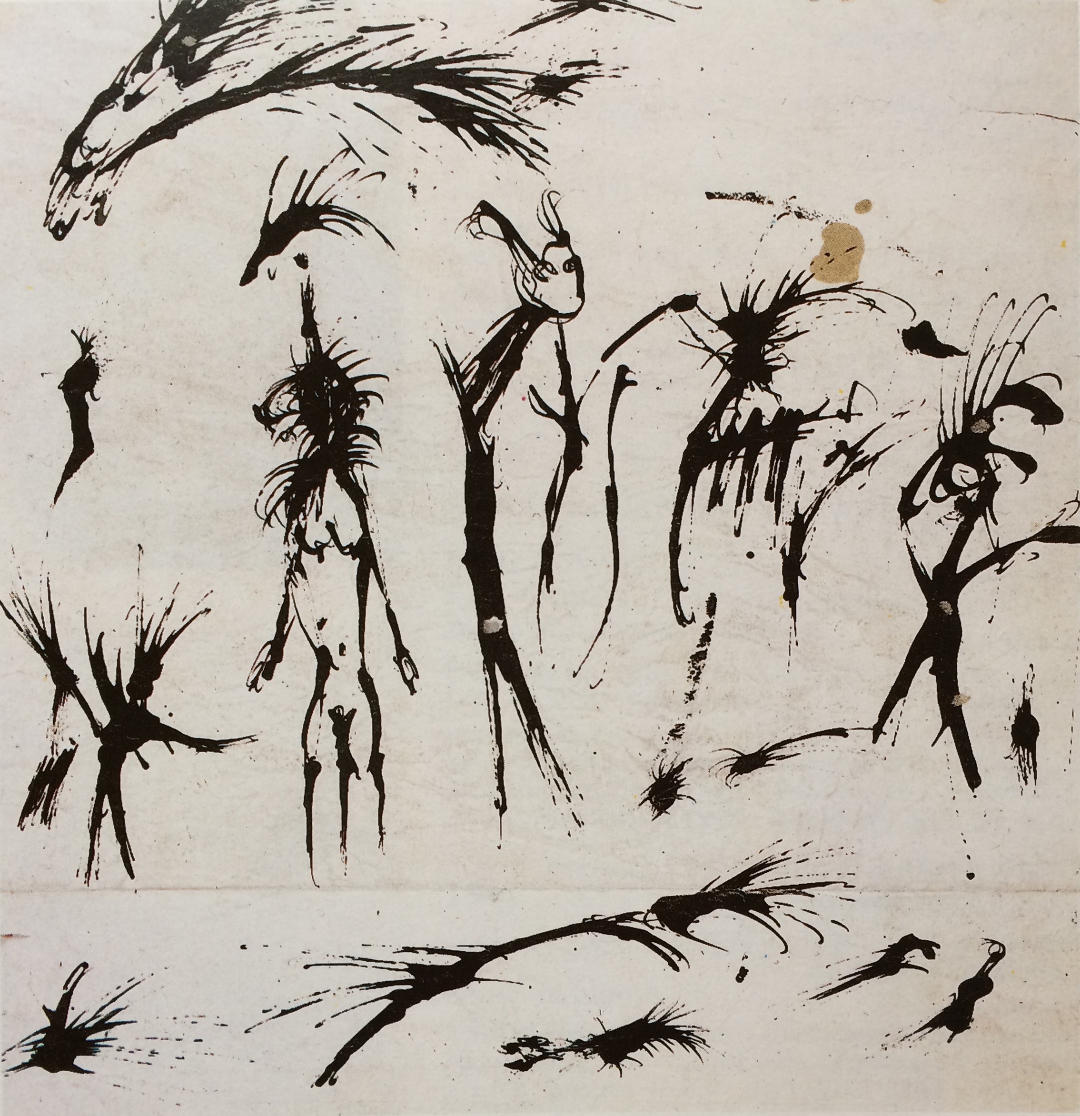

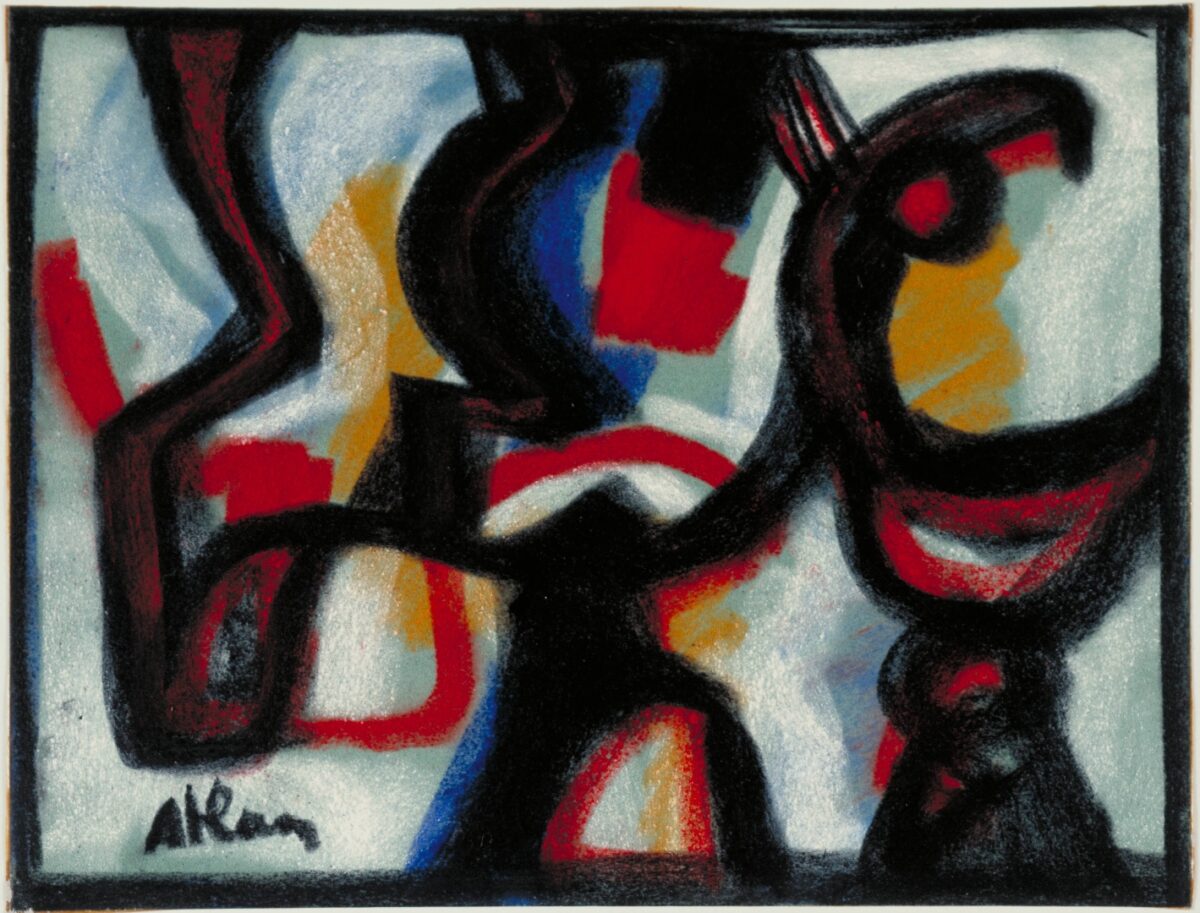

The works by Atlan in The Museum of Modern Art’s collection represent both periods of the artist’s activity (which were separated by a reclusive time of low visibility for Atlan from 1947 to 1957, although he was still working): lithographs and line blocks created by Atlan in 1945 for Description of a Struggle (Description d’un combat) by Franz Kafka, an illustrated book published in 1946, and Realm (Royaume), a pastel on colored paper made by the artist in 1957. Despite being created ten years apart, the sign is present in both works.11The concept of sign painting, coined by Algerian poet Jean Sénac (1926–1973), was an important aesthetic trend amid Algeria’s decolonization and post-independence period. It was historically aligned with a desire for cultural reappropriation through the spotlighting of Arabic and Berber writing, as well as ancestral geometric signs. While the 1945 prints foreground the plastic potential of the sign, his later pastel establishes its use as a means for the artist to relate to the world around him.

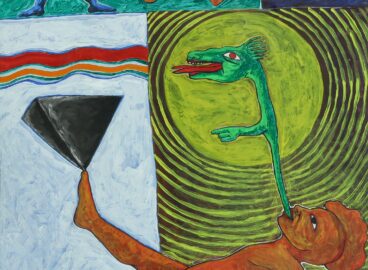

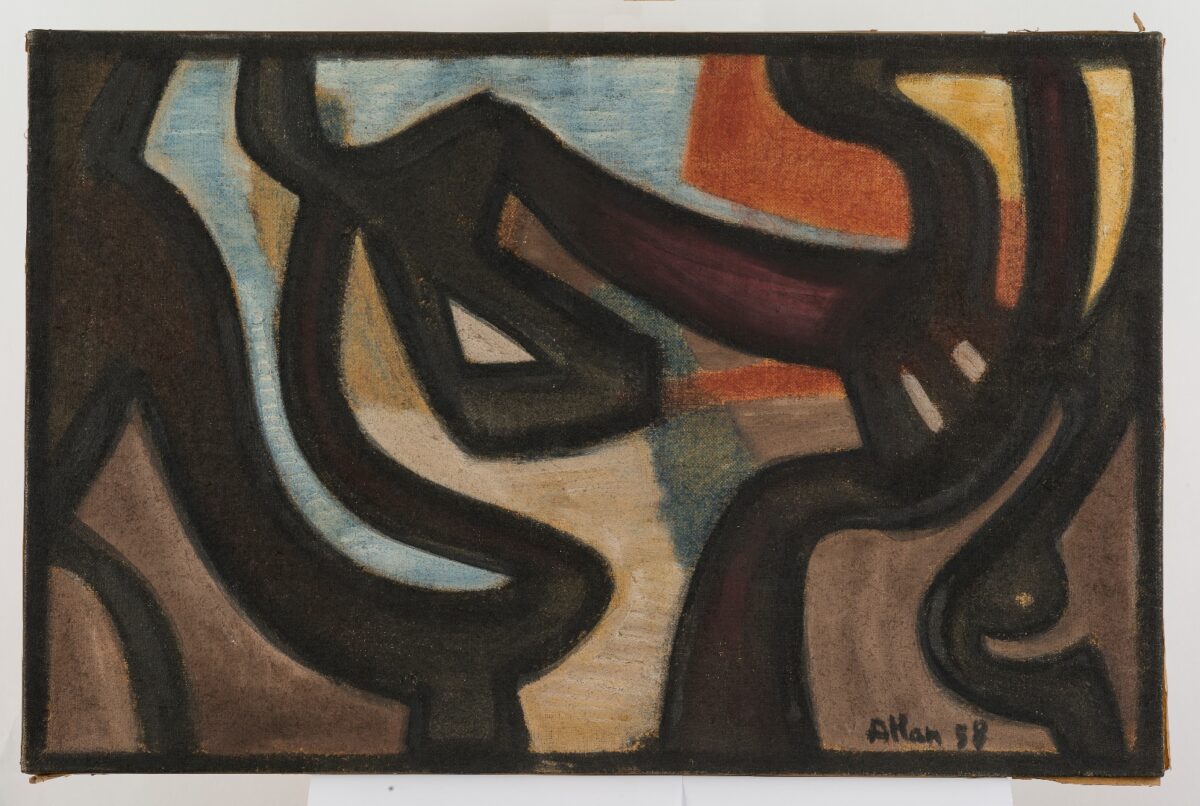

Atlan progressively developed images incorporating biomorphic forms and strange signs. What were his sources of inspiration? Perhaps Arabic calligraphy, which he had encountered in many forms, including in the epigraphic decors of mosques and Islamic monuments in Constantine, such as in the famous madrassa on rue Nationale by his parent’s house? Maybe Hebrew calligraphy, with its graphic and esoteric dimensions? Or Berber motifs used in the decorative arts and symbols to ward off evil? Indeed, Atlan recalled seeing “Berbers tracing geometric signs, making little triangles or zigzags on pottery.”12Raymond Bayer, ed., Entretiens sur l’art abstrait, Collection “Peintres et sculpteurs d’hier et d’aujourd’hui” (Genève: P. Cailler, 1965), 223–52. Or ideograms from Japanese culture, with which Atlan felt a close affinity? In Atlan’s visual world, everything is sign and can truly be grasped only through understanding a mysterious language all his own. Atlan constructed his work over a fifteen-year period under the reign of the sign, using lines that are sometimes sharp but more often supple and cursive—signs that, like language, have endless variations. Everything feels connected, both surprisingly open and yet equally mysterious: black forms emerge as abstract signs, or as stylized silhouettes of humans, birds, and trees, or a combination of all these morphing together in metamorphosis—a process central to the artist’s magical universe. Some of his works evoke the Maghreb,13See, for example, Les Aurès (The Aurès, 1958), Peinture berbère (Berber Painting, 1954), La Kahena (Al-Kahina, 1958), Maghreb (1957), and Rythme africain (African Rhythm, 1954), etc., among others. but the majority make no reference to it, leaving the viewer unconstrained in their visual experience and the enigma preserved.

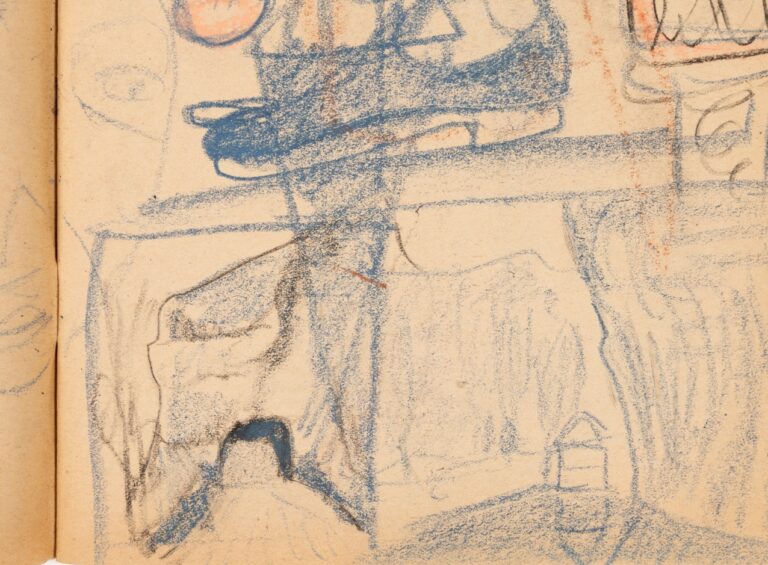

Movement and gesture are embedded in his work. From his earliest ink drawings to his collection of pastels, Les Miroirs du Roi Salomon (King Solomon’s Mirrors), which was published posthumously, calligraphy proved to be consistently significant for the artist. In his illustrations for Kafka’s Description of a Struggle, Atlan transmuted this calligraphy into his own writing. As part of his first contract with Galerie Maeght, at the suggestion of Georges Le Breton and Clara Malraux (who translated Kafka’s text into French), Atlan created a series of lithographs to illustrate the edition for its September 1946 publication.14Franz Kafka and Jean-Michel Atlan, Description d’un combat, trans. Clara Malraux and Rainer Dorland, preface by Bernard Groethuysen (Paris: Maeght, 1946). Working with lithographer Fernand Mourlot proved vital to his work: “My contract with Maeght led me to Mourlot’s lithograph studio, where I worked with stones for a year. This time was incredibly enriching for my painting—the black and white taught me about color. In black-and-white work, I discovered light and matter.”15Ragon and Verdet, Jean Atlan, 60.

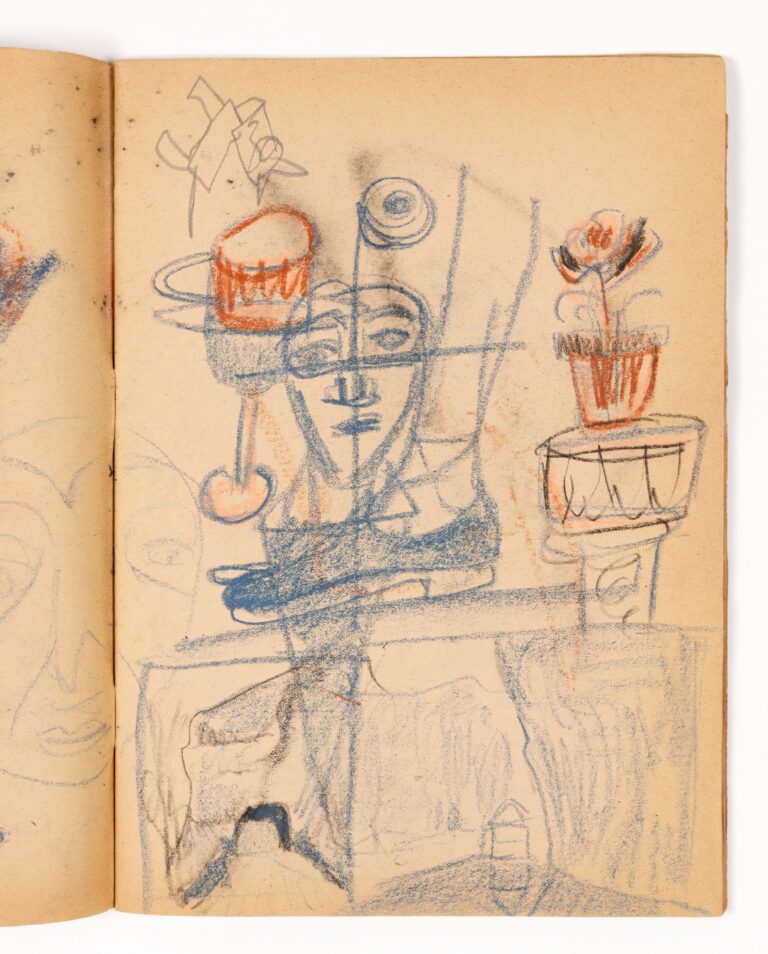

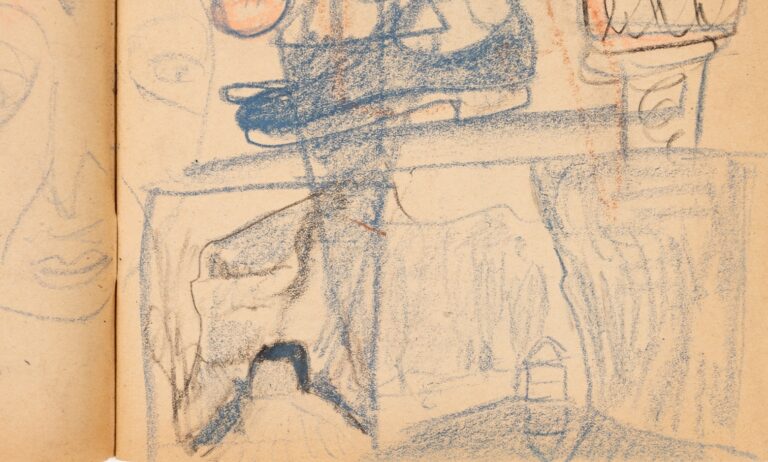

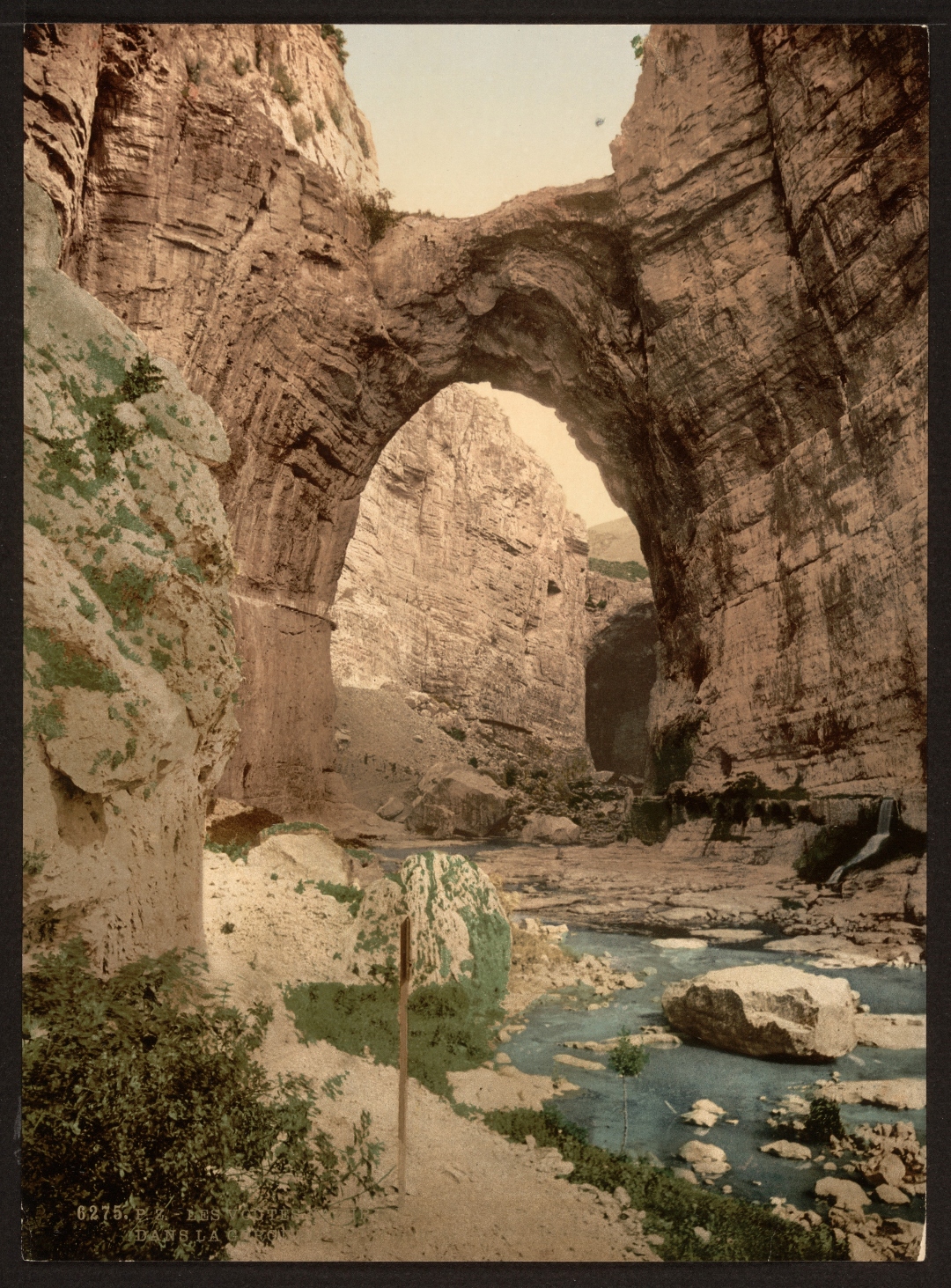

He persistently pursued material investigation, driven by a desire to find the best way to bring his forms to life.16Jacques Polieri and Kenneth White, Atlan: Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre complet (Paris: Gallimard, 1996), 641. He explained his choice of materials as follows: “I needed a medium like fresco or oil paint, which led to my absorbent preparations using sackcloth canvas and to mixing powders, oils, and pastels.”17Polieri and White, Atlan. Just as a line cuts across to create a symbol, the direct application of pastels—which cannot be covered or redone—contributes to the expressivity of his gestural painting. Atlan’s large oil canvases from this period owe their sumptuous nature in part to the work he was doing on paper at the same time, including in distemper and pastels. His research on color, such as silver, white and ivory black, as well as the absorbent abilities of his mediums, led to his becoming “a modest yet incredible craftsman,” as Michel Ragon put it.18Michel Ragon, in “Atlan 1913–1960,” Michel Chapuis’s radio show, Témoins (Witnesses), January 14, 1971, broadcast by ORTF on channel 2. He dedicated himself to pastels when the technique was considered outdated and had become largely obsolete in contemporary art. But Atlan was not swayed by fashion, and he worked in that medium (among others) because of its mineral aspects, which evoked earth colors and the ocher of rock. This was undoubtedly inspired by memories, such as of the magnificent, towering plateau upon which Constantine is built.

Conjuring a mental image of his home city, by then far away, he said of the sketches he made in his notebook, “I have Judeo-Berber origins, like almost everyone there in the old city . . . which was built with stone, gullies, eyries, and cactus.”19 Bénézit, Dictionnaire critique et documentaire des peintres, sculpteurs, dessinateurs et graveurs, 520–22. With his propensity for these techniques, his soot-black lines, his symbols from another age, and his ocher colors, Atlan offered the viewer glimpses of the cultural substrate that inspired him and created a staunchly modern work that nonetheless maintained a firm grip on its cultural references. His friend, the artist and poet André Verdet (1913–2004), used these audacious words when speaking of Atlan: “This undercurrent of Afro-Mediterranean civilizations . . . Jean Atlan bathes in the very humus of eras archaic, beyond neolithic.”20 Ragon and Verdet, Jean Atlan, 23. Therewith related, it is noteworthy that from November 1957 to January 1958, the Musée des arts décoratifs in Paris was showing explorer Henri Lhote’s exhibition on cave paintings discovered in Tassili n’Ajjer, Algeria—an exhibition that resonated with several modern artists. In the case of Atlan, the artist told Pierre Alechinsky (born 1927) that the cave metaphor ran through his work. He admitted that, according to him, art and beauty are to be found deep within it.21Pierre Alechinsky refers to his conversations with Atlan in Alechinsky, Des deux mains (Paris: Mercure de France, 2004), 62. Alechinsky confirmed the fundamental place that fantasies of prehistoric discovers occupied in Atlan’s mind.

While not discounting the primordial role of migration in sparking and intensifying memory, everything points to the fact that for Atlan, these recollections and legacies were more than fixed and inert backdrops; instead, he saw them as pliable material for an inventive imagination, freed by gesture to enter the work, reactivated endlessly in creations in which signs and colors combine to give profound coherence and constant renewal.

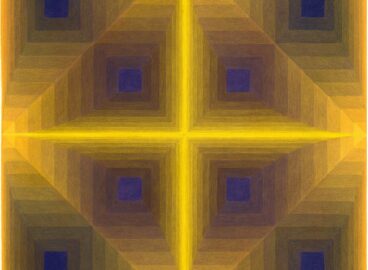

Atlan seemed to play with materials and mediums to construct his pictorial space: juxtapositions and superpositions reveal the intense vibrations of his colors. He used the expressive potential of vivid hues to their greatest effect, contrasting them with the black forms that structure and invigorate the space. Indeed, Clara Malraux remarked on how the colors and signs were in tension, bringing a rhythm to the heart of his works.22 Clara Malraux, The Contemporaries and Theodore Schempp present Atlan, Recent Paintings and Gouaches, March 21 to April 9, 1960, exh. cat. (New York: The Contemporaries, 1960), unpaginated. In the same period, Atlan himself discussed rhythms in dance and painting as a symbol of life, such as in “Letter to Japanese Friends,” which he wrote shortly before his death.23 Hand-written notes of Jean-Michel Atlan, undated. BK, Atlan collection, shelf ATL 70. Published in December 1959 as “Lettre aux amis japonais,” in Geijutsu Shincho 10, no. 12 (December 1959). In this text, he calls painting an “adventure that confronts man with the formidable forces within and outside of him: destiny and nature.” The rhythm, tension, and violent expressivity in his works add a tragic dimension that reflects his internal suffering and the impact of the conflicting worlds he had lived through.

Realm (1957) is among the works he produced in his later period of intense creative activity and public exposure. As with other paintings and pastels from this time, the space has been refined, and the composition focuses on fewer, more majestic signs. The artist stages polysemantic forms that appear to be contemporary and personal interpretations of arabesque decoration. Likewise, the presence of rhythm is felt: The forms dance within the painted field, and the viewer can picture them continuing beyond the frame despite the black line that borders it. These shapes seem backlit in a mysterious procession, connected through an entanglement that evokes the idea of metamorphosis. Ocher, red, chalk white, and a few blue highlights lend a strange and uncertain luminosity contrasting with the foreground’s dark scrim. This tension between light and dark, line and color, is accentuated by the texture and shade of the paper, deliberately left exposed akin to the strokes of a pen.

Characterizing Atlan’s Works: Decentering the Gaze, Moving beyond Categories

The two works by Atlan in MoMA’s collection, along with others that are emblematic of his style, such as the large paintings he created from the mid-1950s until his death, reinforce the idea that his art cannot be confined within the artistic categories of Europe at that time. Although mainstream formal logic opposes figuration and abstraction, this binary thinking does not apply to Atlan’s paintings. Today, this fluidity would easily be accepted, but it was a source of debate in the postwar period.

The terms “lyrical abstraction” and “abstract expressionism,” more suited to postwar tastes, likewise did not satisfy the painter, as he did not embrace either one. Michel Ragon put forth the notion of “other figuration” to describe Atlan’s work after his early Art Informel period. In a discussion, Atlan told him that he preferred the term “other art,” suggesting that he didn’t want to be confined to a trend or to be boxed in stylistically.24 This discussion and others are recorded in Atlan, the book that Michel Ragon dedicated to his friend after his death. Ragon, Atlan, 62–63. For Ragon, this so-called otherness stemmed largely from the artist’s embeddedness in North African culture and history.

Ragon and other critics then began to use the term “barbarism”—often associated with the idea of rhythm—to characterize his art. This word, as well as “primitivism,” were used to describe Atlan’s output, but each has its own level of ambiguity: the former oversimplified his approach, while the latter decontextualized his original anchoring, placing it within a different cultural arena. Beginning in the 20th century, many European artists attempted to tackle the non-Western universe of signs, seeking to emphasize the notion of primitivism. This idea, embraced by artists such as those associated with CoBrA, including Asger Jorn (1914–1973) and Corneille (Guillaume van Beverloo; 1922–2010)—with whom Atlan exhibited in 1951—does not align with his intentions.25King Baudouin Foundation Archives, Christian Dotremont collection, shelf CDMA 02400/0003, anonymous letter to Dotremont, February 1951, regarding the exhibition that took place in Brussels with members of CoBrA. Two of Atlan’s works were shown there, but the writer complained to Dotremont about Atlan and Jacques Doucet’s lack of involvement in the group: “I told you that Atlan and Doucet wouldn’t take care of anything. I’m sick of begging them to take an interest in Cobra.” Similarly, among the practitioners of lyrical abstraction, his approach bore no similarities to that of Georges Mathieu (1921–2012), for example, who was becoming famous in Paris around the same time for extolling a type of gestural painting inspired by the calligraphic arts of the Far East. Without a doubt, the postwar context was a suitable one in which to challenge the supremacy of European art. Still, unlike European artists, who were decentralizing their views to understand the world better, Atlan’s evolution was in colonized Algeria, where he had constructed his visual universe; furthermore, he could speak from within the subjugated societies resisting that domination in their own ways. He was not coming from the outside; he was no stranger to the universe of forms other artists would appropriate and use. He claimed to belong within it, first through his political engagement during his youth and then solely through his aesthetic after the war.

In this decentring of the gaze, the question arises whether Atlan’s works relate in form to the Algerian painters who were also in Paris during the 1950s. Those from the generation born in the 1930s took an interest in Atlan’s work upon arriving in Paris. Among the Maghreb painters in the modern era, there is formal proximity with the so-called painters of the sign (“les peintres du signe”), such as Moroccan artist Ahmed Cherkaoui (1934–1967) and Algerian artists Mohammed Khadda (1930–1991), Choukri Mesli (1931–2017), and Abdallah Benanteur (1931–2017), for whom Atlan was a predecessor. The concept of sign painting, coined by Algerian poet Jean Sénac (1926–1973), was an important aesthetic trend amid Algeria’s decolonization and post-independence period. It was historically aligned with a desire for cultural reappropriation through the spotlighting of Arabic and Berber writing, as well as ancestral geometric signs like those used for basket-weaving, pottery, rug-making, and tattoos.26 An example is in the manifesto of the Aouchem Group, which formed in Algeria in 1967. In his essay “Elements for New Art,” Khadda stated: “Atlan, the prematurely deceased Constantinian, is a pioneer of modern Algerian painting.”27Mohammed Khadda, Éléments pour un art nouveau (Algeria: UNAP, 1972), 51. We should not interpret this statement as assigning a label or identity but rather as expressing both interest in a new aesthetic and gratitude for Atlan’s work—Atlan paved the way for those artists in that moment in history and helped to legitimize their artistic research.

The Postcolonial Context: Atlan (and Us)

Once idolized, then overshadowed, Atlan is particularly interesting in the postcolonial context: it is necessary to rediscover the vivid work of this precursor, one who used the power of the sign to claim his place in the world at the beginning of decolonization and who underscored the presence of plural modernities within modern art. Critics in his time spoke of the syncretism of his work. By instead referring to the work of Édouard Glissant on creolization, we can go beyond this syncretic vision and reconnect Atlan’s work to other aesthetic experiences that are the result of the creolization of art in the 20th century, a significant source of renewal and a shared universe, recognizing the contributions of each of these actors without having to resort to the idea of hierarchy or centralization.

Translated from the French by Allison M. Charette and Beya Othmani. Click here to read the French version.

- 1Before settling on “Atlan,” he signed his works “J M Atlan” or “J M A.”

- 2For example, see Ernest Bénézit, Dictionnaire critique et documentaire des peintres, sculpteurs, dessinateurs et graveurs [. . .], vol. 1, Aa–Beduschi, new ed. (1911; Paris: Librairie Gründ, 1999), 520–22; or Michel Ragon and André Verdet, Jean Atlan, Les Grands peintres (Geneva: René Kister, 1960), 10.

- 3Resistance fighter certificate from the office of the National Front for the Fight for French Liberation, Independence, and Rebirth, dated April 23, 1949. Bibliothèque Kandinsky (hereafter BK), Atlan collection, shelf ATL 70.

- 4Letter of Atlan to Denise René, February 14, circa 1943. BK, Atlan collection, shelf ATL 85.

- 5Michel Ragon, Atlan, Collection “Le Musée de poche” (Paris: Georges Fall, 1962), 5. Unless otherwise noted, all translations by Allison M. Charette.

- 6Atlan’s first solo exhibition opened in December 1944 at the Arc-en-Ciel Gallery on Rue de Sèvres in Paris. It was hailed by critics, and Jean Dubuffet (1901–1985) wrote to the artist to express serious interest in his distinctive work. See Dubuffet to Atlan, January 4, 1945. BK, Atlan collection, shelf ATL 83.

- 7The term “Art Informel” (from the French informel, which means “unformed” or “formless”) was first used in the 1950s by French critic Michel Tapié in his book Un Art Autre (1952) to describe a nonfigurative pictorial approach to abstract painting that favors gestural and material expression.

- 8Jean-Michel Atlan, Continuity, no. 2 (1945): 12.

- 9“Can we force new forms into concrete existence? Is purely plastic expression possible? It will gradually become clear that the essential task of young painting is to replace the vision of reality with the authenticity and reality of vision.”, in ibid.

- 10As related to Amandine Piel by Pierre Soulages, January 14, 2019.

- 11The concept of sign painting, coined by Algerian poet Jean Sénac (1926–1973), was an important aesthetic trend amid Algeria’s decolonization and post-independence period. It was historically aligned with a desire for cultural reappropriation through the spotlighting of Arabic and Berber writing, as well as ancestral geometric signs.

- 12Raymond Bayer, ed., Entretiens sur l’art abstrait, Collection “Peintres et sculpteurs d’hier et d’aujourd’hui” (Genève: P. Cailler, 1965), 223–52.

- 13See, for example, Les Aurès (The Aurès, 1958), Peinture berbère (Berber Painting, 1954), La Kahena (Al-Kahina, 1958), Maghreb (1957), and Rythme africain (African Rhythm, 1954), etc., among others.

- 14Franz Kafka and Jean-Michel Atlan, Description d’un combat, trans. Clara Malraux and Rainer Dorland, preface by Bernard Groethuysen (Paris: Maeght, 1946).

- 15Ragon and Verdet, Jean Atlan, 60.

- 16Jacques Polieri and Kenneth White, Atlan: Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre complet (Paris: Gallimard, 1996), 641.

- 17Polieri and White, Atlan.

- 18Michel Ragon, in “Atlan 1913–1960,” Michel Chapuis’s radio show, Témoins (Witnesses), January 14, 1971, broadcast by ORTF on channel 2.

- 19Bénézit, Dictionnaire critique et documentaire des peintres, sculpteurs, dessinateurs et graveurs, 520–22.

- 20Ragon and Verdet, Jean Atlan, 23.

- 21Pierre Alechinsky refers to his conversations with Atlan in Alechinsky, Des deux mains (Paris: Mercure de France, 2004), 62. Alechinsky confirmed the fundamental place that fantasies of prehistoric discovers occupied in Atlan’s mind.

- 22Clara Malraux, The Contemporaries and Theodore Schempp present Atlan, Recent Paintings and Gouaches, March 21 to April 9, 1960, exh. cat. (New York: The Contemporaries, 1960), unpaginated.

- 23Hand-written notes of Jean-Michel Atlan, undated. BK, Atlan collection, shelf ATL 70. Published in December 1959 as “Lettre aux amis japonais,” in Geijutsu Shincho 10, no. 12 (December 1959).

- 24This discussion and others are recorded in Atlan, the book that Michel Ragon dedicated to his friend after his death. Ragon, Atlan, 62–63.

- 25King Baudouin Foundation Archives, Christian Dotremont collection, shelf CDMA 02400/0003, anonymous letter to Dotremont, February 1951, regarding the exhibition that took place in Brussels with members of CoBrA. Two of Atlan’s works were shown there, but the writer complained to Dotremont about Atlan and Jacques Doucet’s lack of involvement in the group: “I told you that Atlan and Doucet wouldn’t take care of anything. I’m sick of begging them to take an interest in Cobra.”

- 26An example is in the manifesto of the Aouchem Group, which formed in Algeria in 1967.

- 27Mohammed Khadda, Éléments pour un art nouveau (Algeria: UNAP, 1972), 51.