Just as people continue their journeys by transferring from one type of transportation to another, an artwork can continue its creative evolution by transferring from one medium to the next. A talk and performance by Shiomi presented in conjunction with the exhibition MOT Collection Chronicle 1964–: Off Museum at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, on April 29, 2012.

Good afternoon, everyone.

The title of the program is “Intermedia/Transmedia,” but my focus today is on transmedia. This is a made-up word that I came up with while reflecting on my past work, and it has to do with the creation of conceptually related works in different mediums. For example, if I start with an Event, I turn it into an object, a musical work, and then into a video. The original concept is carried into subsequent works even though the form of expression is different each time.

There is a travel term, “transfer” or “transit.” Just as people continue their journeys by transferring from one type of transportation to another, an artwork can continue its creative evolution by transferring from one medium to the next. Have you heard the word “transmedia” before? I ask because there may be somebody somewhere using the same word but with a different meaning, even though I thought I made it up. There are so many words regarding mediums and media, and it can be confusing. If you say that I’m making it even more confusing, that’s true (laughter).

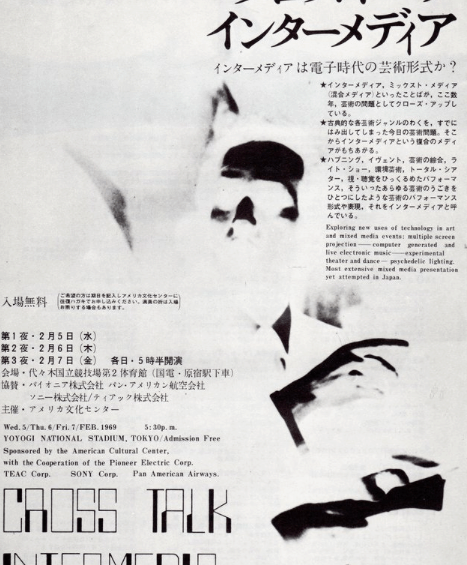

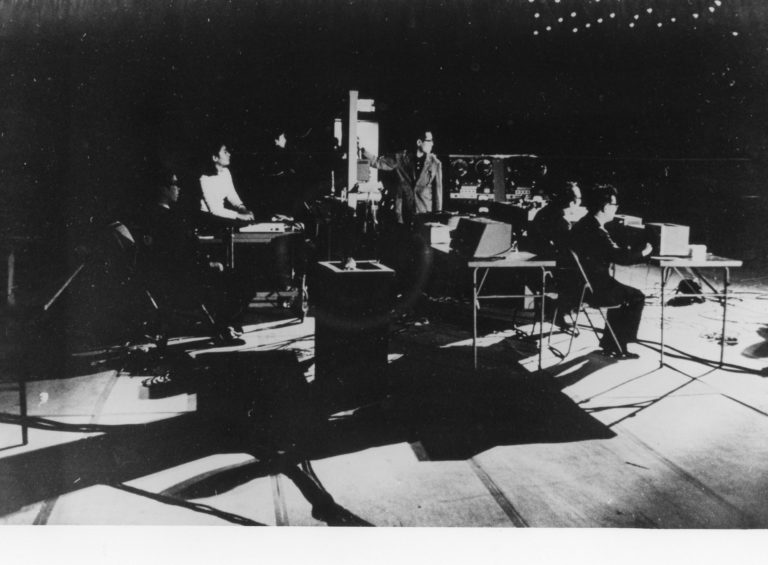

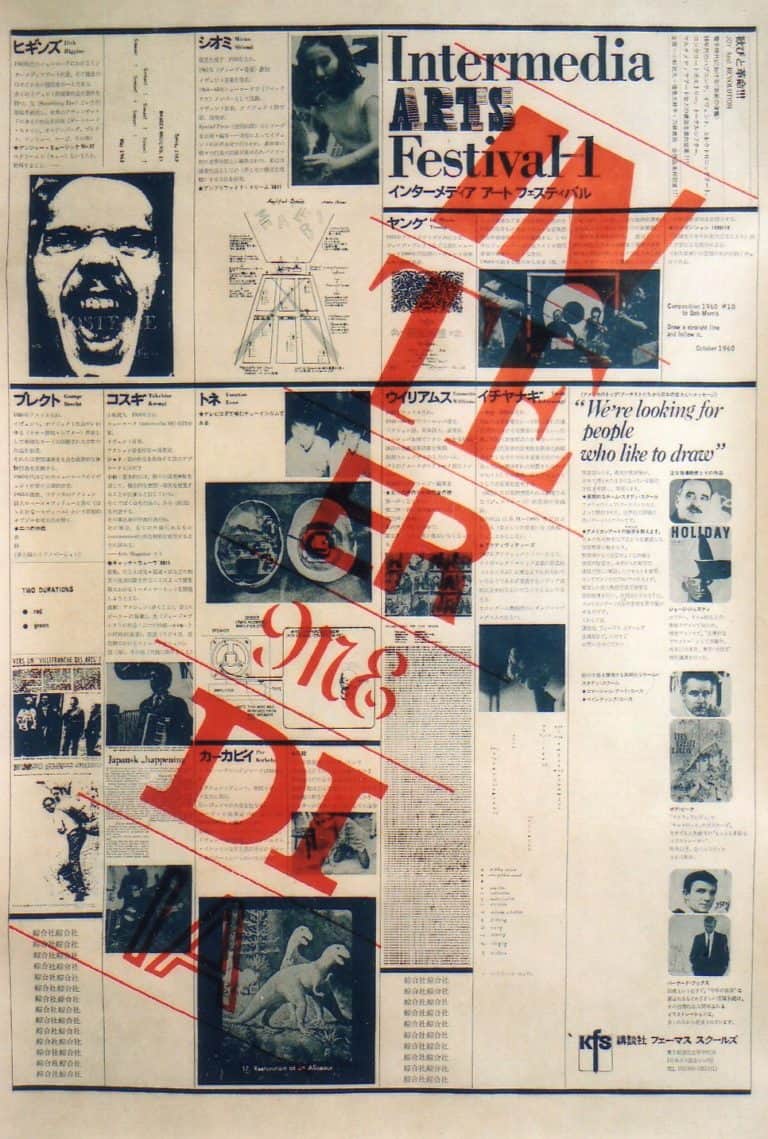

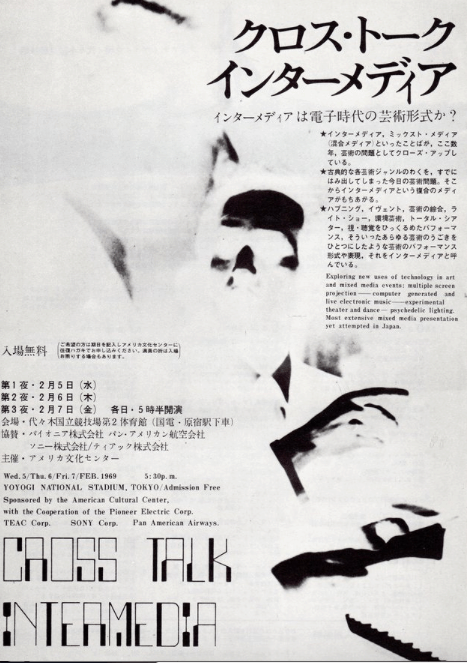

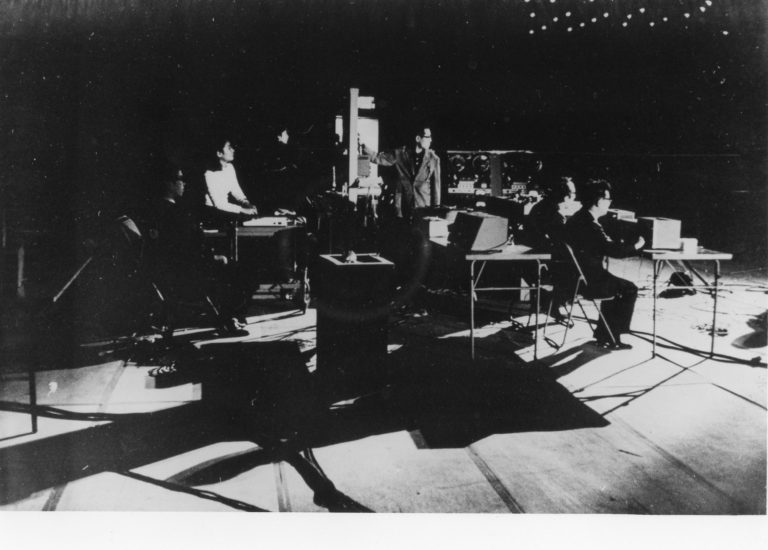

Today, “media” often refers to mass media such as television and newspapers, while media art encompasses even manga and anime in addition to various forms of digital art. However, when Dick Higgins of Fluxus promoted the idea of “intermedia” in 1960s, he defined it as follows: “the form of expression which falls between the existing genres such as poetry and music, for example, vocal poem or visual poem.” We also used to interpret the word “media” merely as a medium for artistic expression, for example, sound, language, light, object, and image. Thus, the meaning of the word has changed over time. In 1969, Kosugi Takehisa, Tone Yasunao, and I, of Group Ongaku (Group Music), organized the “Intermedia Art Festival” in Tokyo [Fig. 1]. This is the poster for it. The man with his mouth wide open is Dick Higgins. I think this is a photograph of him performing his piece Danger Music No. 17. The instruction for it consists of the word “Scream!” repeated six times. In this three-day festival, we performed about twenty Fluxus works interpreted through our understandings of the technologies and concepts of intermedia. Unfortunately, there is no record of these performances. Two weeks later, Cross Talk/Intermedia was organized by Yuasa Joji, Akiyama Kuniharu, and Roger Reynolds [Fig. 2]. Since this event was hosted by the American Cultural Center in Tokyo, several artists were invited from overseas, and ambitious performances were included. I presented Amplified Dream I at Cross Talk/Intermedia and II at the Intermedia Art Festival. Though the works have the same title, the contents were totally different from each other. This image shows where the sound manipulation was taking place in the corner of the vast space inside the Yoyogi National Gymnasium [Fig. 3]. There was a spacious area to the right of this corner where the performance was held around three grand pianos, a large, made-to-order windmill, and a fan. What the two works had in common was a very tightly knit structure, partly using electronic technology, which enabled the progress of the whole event through mutual feedback of sound, light, the rhythm of Morse signals, projected texts, and movements of the human body. If even one of these elements had been missing, the whole would not have worked. This is what makes it different from “multimedia.” At that time, all media of equal significance were available to me. The experience of intermedia became a foundation for me to move to the next step of transmedia. Now, I would like to use several examples and talk about how I created them as transmedia. Some of them will be actually performed later.

Disappearing Music for Face

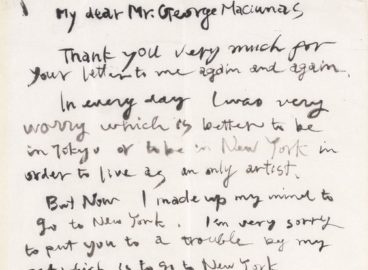

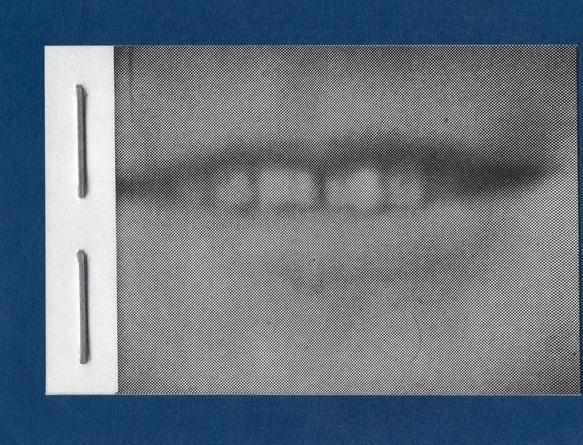

The oldest example is an Event called Disappearing Music for Face. The instruction read simply: “Smile, and make it disappear gradually.” The premier was done with Fluxus friends and the audience at Washington Square Gallery in New York in 1964 [Fig. 4]. This was the first day of the Perpetual Flux Fest that George Maciunas organized. To my right is Alison Knowles. As my English was poor at the time (it is still poor even now), she volunteered to conduct the performance instead of me. The photo is from forty-eight years ago. We were both young.

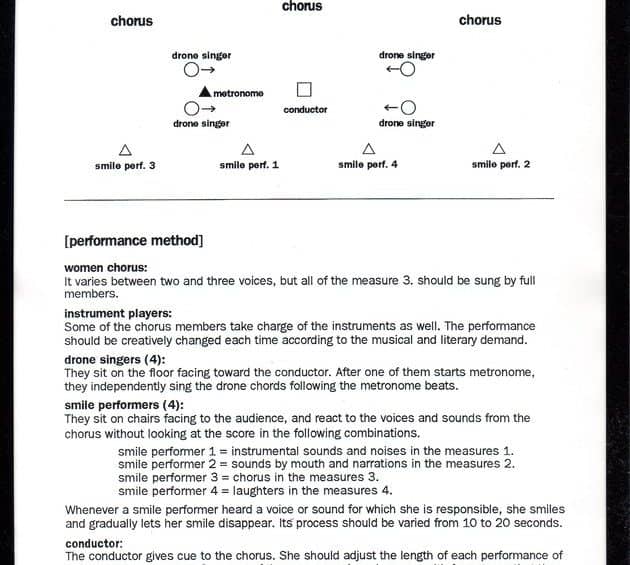

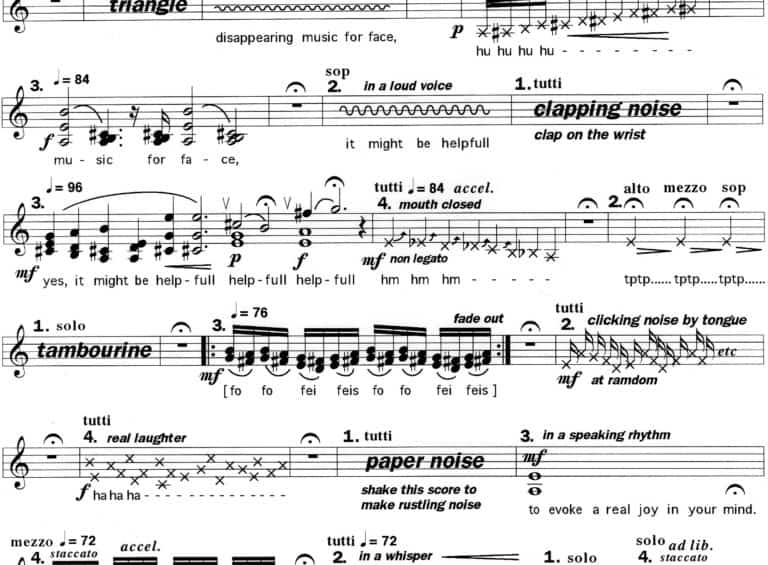

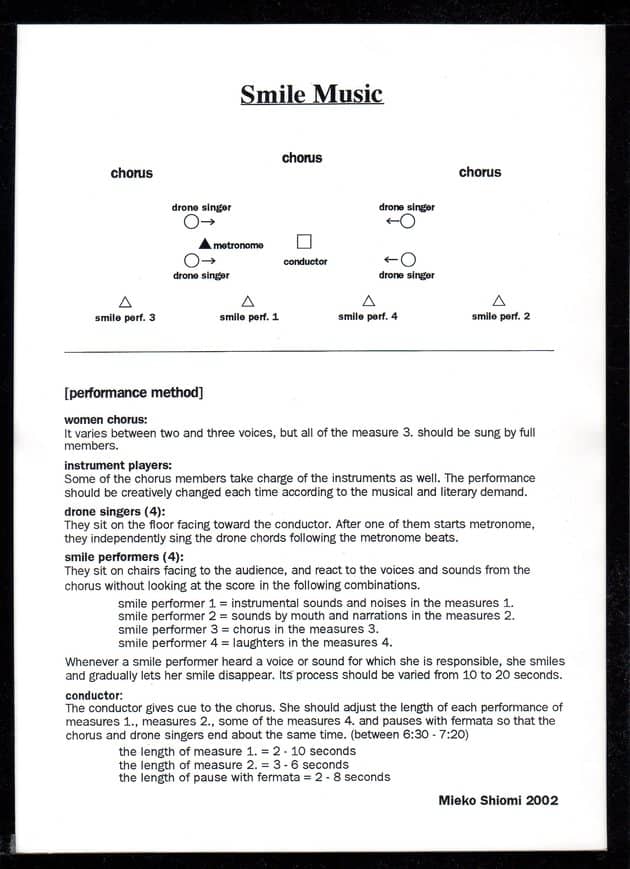

Soon, Maciunas made an 8mm film out of this Disappearing Music for Face, with Yoko Ono as the performer and Peter Moore as cameraman. Along with others’ works, this became part of Fluxfilms. In Japan, it is in the collection of the National Museum of Art in Osaka. Later, Maciunas extracted a few frames from the film, printed them, and turned them into a flip-book [Fig. 5]. When you see it on the screen now it looks large, but the book’s actual size is four by six centimeters [approx. 1 9/16 x 2 3/8 in.]. It fits into the palm of your hand. There are thirty-nine photographs, and the smile gradually disappears when you flip the pages. It is very clear. Flip-books are fun even now, aren’t they? Your fingers’ actions cause an illusion of moving image. I feel as if I could imagine the pleasure of the person who invented it and made it first. On the last page, there is a history of this flip-book [Fig. 6]. According to this, it was produced by ReFlux in 2002, in an edition of seventy-nine, from the printed matter left by Maciunas. Five copies were sent to me. So, transmedia was a method begun by Maciunas, as far as my work is concerned. Of course, he didn’t use such a word. I think the word “media” itself was not used much until Dick Higgins started promoting intermedia. Later in 2002, Michele Edwards, musicologist and conductor of a choir in Minnesota, visited me and asked me to make a new performance piece for her choir, based on my earlier Event. I composed a choir piece, Smile Music, based on Disappearing Music for Face. This diagram shows the positions of the choir on stage: the top is the choir, consisting of soprano, mezzo soprano, and alto; the middle is a group that sings drones; and seated at the bottom are four smile performers. They are instructed to smile in reaction to specified sounds made by the choir [Fig. 7]. For example, smile performer one smiles to the sounds of small instruments and noises in the first measure. Smile performer two smiles to vocalized sounds and narrations in the second measure [Fig. 8]. The lyrics for the choir are “When you perform… Disappearing Music for Face… It might be helpful… to evoke a real joy in your mind… For instance… Imagine that you saw a glaring sun set over the ocean… While you make your smile disappear… try to keep imagining… the magnificent sun sinking very very slowly into the horizon… ” The score advised the four smile performers on how to smile and how to make their smiles disappear.

This way, the original Event piece became an eight-millimeter film, then turned into a flip-book, and then into choral music. Even now, the evolution might not be finished, and there may be a possibility of making a new work in a different medium. Today, after a break, I would like some people to perform a new complex version of Disappearing Music for Face.

Endless Box

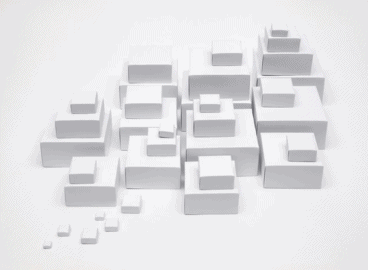

The most recent example is a video work based on my Endless Box. The video shows a sequence of opening white boxes. It was produced especially for this exhibition. Originally, the museum suggested that we make a video recording of me as the creator opening the boxes as a sort of documentation for the archives, but I insisted on them asking a third person to make a new video work based on my work. Coincidentally, the hands of the curator Fujii Aki, to whom I was talking about this, looked very beautiful and triggered an image in my mind of her hands opening the white boxes against a dark background. Then, I requested them to make a video that would focus just on hands and the boxes, which become smaller as the opened boxes would be stacked out of site. Video artist Yamashiro Daisuke made the video, and such a beautiful moving image was born.

Originally, I made Endless Box in 1963, as an object which visualized diminuendo, a musical term referring to a sound gradually decreasing in loudness over time.1In the German musical system, “H” refers to the seventh scale degree, and the “B” refers to the flatted seventh scale degree of a seven-note diatonic scale. —Editor’s note. Actually, a transmedia conversion of turning a sound into an object took place in my head at that point, but I was not conscious of it at all back then. When I watch this recent video, those moments are represented and I feel as if I returned to the point when I created the boxes. For that reason, too, I’m grateful to these two persons who made this video possible.

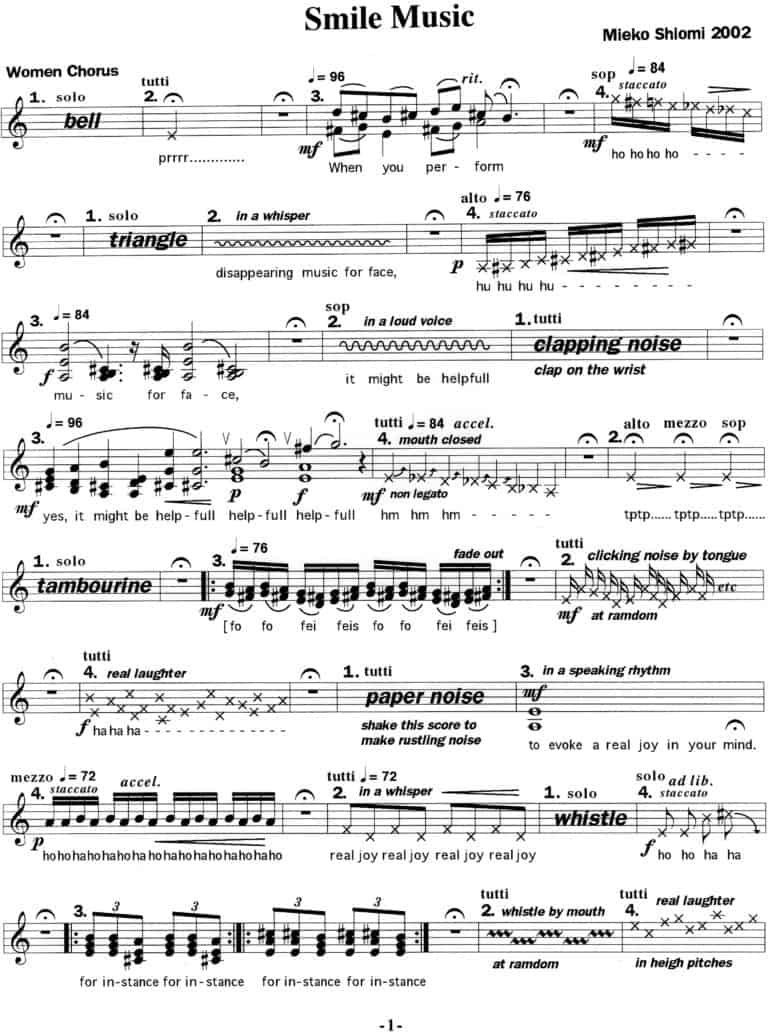

I’ve also used Endless Box in a performance. I made a larger version using thicker sheets of paper, and I used it three times on stage. The first time was during the piano and musical performance of A Trick of Time (1984). In it, a performer slowly opened the boxes in the center of the stage and arranged them into a line towards both sides of the stage. It was as if we were watching an afterimage of time that has flown away. This is a photograph of the 1992 performance at Art Vivant in Tokyo [Fig. 9]. Since I didn’t have any photographs of the event, I scanned a page from an issue of Bijutsu Techomagazine. The title of this thirty-minute piece was And a Nightingale Has Flown. As a bird sound traveled between the two speakers, from left to right and right to left, a woman opens Endless Box one by one and stacks them up on top of the lid of the grand piano. Here a performance of various actions related to the concept of opening took place. There were several music boxes on the piano, and it was possible to open and close their lids. In addition, the man on the right is opening envelopes one by one and reading the letters inside, which were translations of the reports sent back to me at the time of Spatial Poem No. 5: Opening Event. In these ways, an image of decreasing sound became an object, and then the object was used in performances, and now it has become a video.

Water Music

Now I will talk about Water Music. This was an Event written before I went to New York in 1964, and it read: “1. Give the water still form. 2. Let the water lose its still form.” As a souvenir for Maciunas, I brought him a small bottle of water with an instruction to “give the water still form.” He liked this souvenir and drank up the water in it, saying that he was performing 2. Excuse me now. I am also going to perform Water Music [Shiomi poured water into a cup and drank it ]. Soon, Maciunas made an edition of these bottles [Fig. 10]. This photo was used for a postcard when the Guggenheim Museum SoHo in New York held the exhibition Japanese Art After 1945 in 1994, but the photo was taken much earlier. I next performed this piece during Flux Week at Crystal Gallery in Tokyo in 1965 [Fig. 11]. To explain what I was doing, I was repeatedly playing on a turntable an SP record that had a layer of water-soluble glue on it. When I dropped water from a syringe onto the record, the glue softened partially to reveal the surface of the record, and the player produced music from those areas while skipping the dry areas. As I increased the number of water drops gradually, more glue was gone and the music slowly became identifiable. This is a record that I used then, and the music was [Carl Maria von] Weber’s Aufforderung zum Tanz (Invitation to the Dance) [Fig. 12]. I inherited it from my parents, but there are scars from the needle on the central label, and it was a harmful performance for the disc. I also did a performance that made the water lose its still form. This is from the performance of Water Lab during the Media Opera concert at Xebec in Kobe in 1992. I was playing a water basin as a percussion instrument and was hitting the water surface with an upturned cup [Fig. 13]. It looks like the performer is fooling around with the water, but it makes interesting sounds.

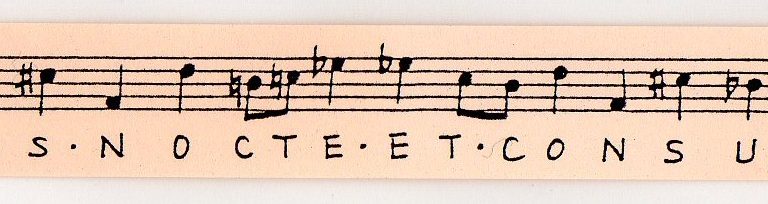

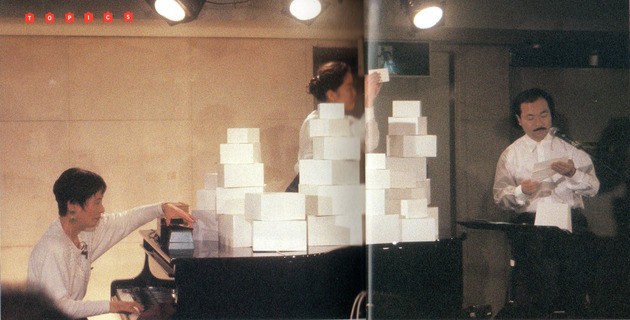

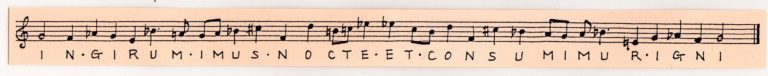

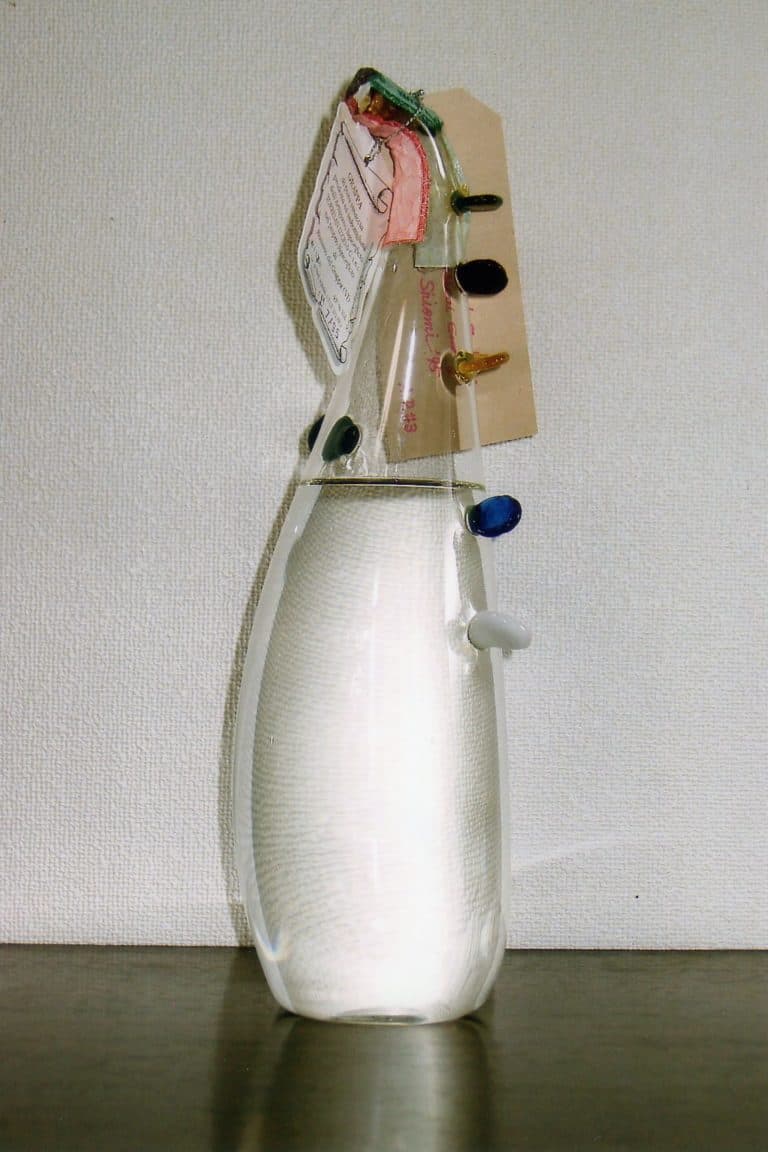

The water bottles as “objects” is the only transmedia version of the Event Water Music, but I also have a work involving the same medium of bottles while switching the concept. I could call it “transconcept.” The series of Small Bottles of Music shown [at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo] is an example of this. The bottles contain scores and tapes of various sorts of music. For example, Sonic Palindrome contains a score that I wrote as accompaniment for a Latin palindrome and a tape of its performance [Fig. 14]. The palindrome was sent by Gianni Sassi for my project Fluxus Balanceand read “in girum imus nocte et consumimur igni.”2Sassi was an avant-garde cultural impresario in Milan and well-known supporter of Fluxus. —Editor’s note. According to a friend who knows Latin, the meaning is “toward a circle we go at night and become absorbed by fire” [Fig. 15]. It is somewhat mysterious and very worldly at the same time. Is there anybody here who is familiar with this palindrome? The melody I composed also reverses from its center. The tape recording of this by a synthesizer is inside the left bottle. The bottle on the right contains a tape recording that mechanically reversed the original melody. That is to say that the sounds in the two bottles also form a palindrome. This series is filled with various musical concepts and jokes, using capsules with musical mottos in them, fragments of CDs, silicon rocks, and pepper. I made the series for the Sound Objects exhibition in Cologne.

Speaking of the bottles, I also made a series called Grappa Fluxus, when the Italian collector Luigi Bonotto (the man wearing glasses, second from right in the photo) gathered designs and ideas from Fluxus artists and asked his friend Massimo, a glass artist, to make the bottles (at the far right in the picture). This photo was taken when I visited the glass studio in Molvena, in Northern Italy, in order to sign the finished bottles [Fig. 16]. This is called Musical Embryo, which I designed, imagining an undeveloped instrument in the form of a fetus [Fig. 17]. And this is The Twelve Embryos of Music, created in an edition of twelve [Fig. 18]. This blue bottle contains a tape recording of very hesitating and awkward performances (as if music were taking its initial form) of twelve different kinds of preexisting musical forms, such as prelude and arabesque.

Although I diverted from the central theme, Water Music has various possibilities of performance. This is from the performance at Lake Shojin, organized by Gallery 360° to celebrate the seventieth birthday of Ben Patterson [Figs. 19–21]. Ay-O sent these photographs to me. Is Mr. Ay-O here? [Addressing Ay-O in the audience:] I’m sorry, this is after the fact. I should have asked for your permission to use these photos today [laughter]. Here, everybody takes a cup of water from the lake and holds it up to the position that matched the summit of Mt. Fuji. On the signal of the leader announcing “Happy Birthday,” each person dripped the water at a random speed. When one person finished, the next would begin. Everybody waited until the last person finished the performance. Today, we will see another realization of Water Music in a performance following this talk.

Balance Poem

I have been interested in various natural phenomena and in the idea of balance in nature since the 1960s, and I’ve created works concerning those interests. I wrote the score for a performance, Balance Poem, in 1966, but it was never performed, and I made an object that consists of a small scale printed on cardboard on which people can weigh words printed on smaller cards with different conceptual weights. This is a photo of this object when it was displayed in the exhibition Tiny Tiny Exhibition at Matsuya Department Gallery in Ginza, Tokyo [Fig. 22].

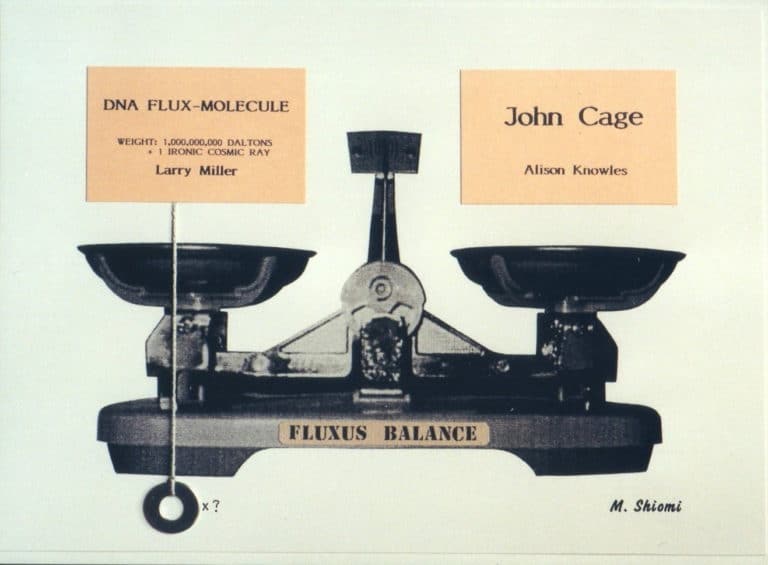

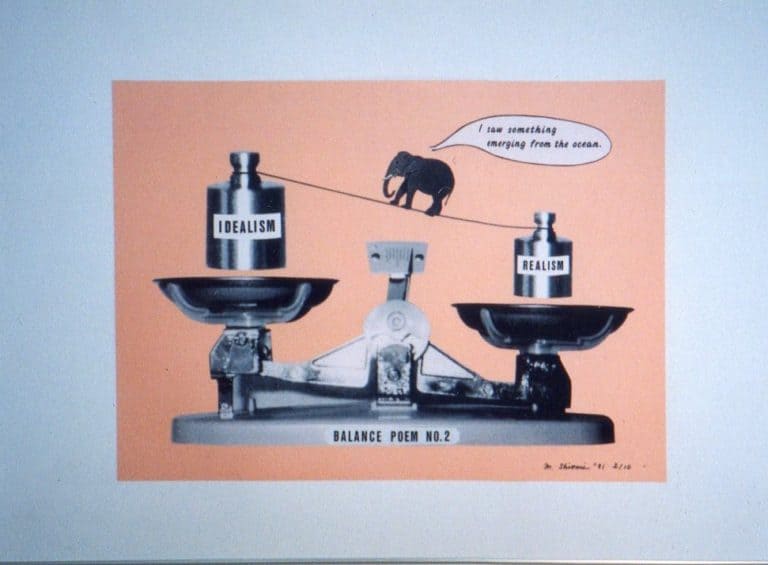

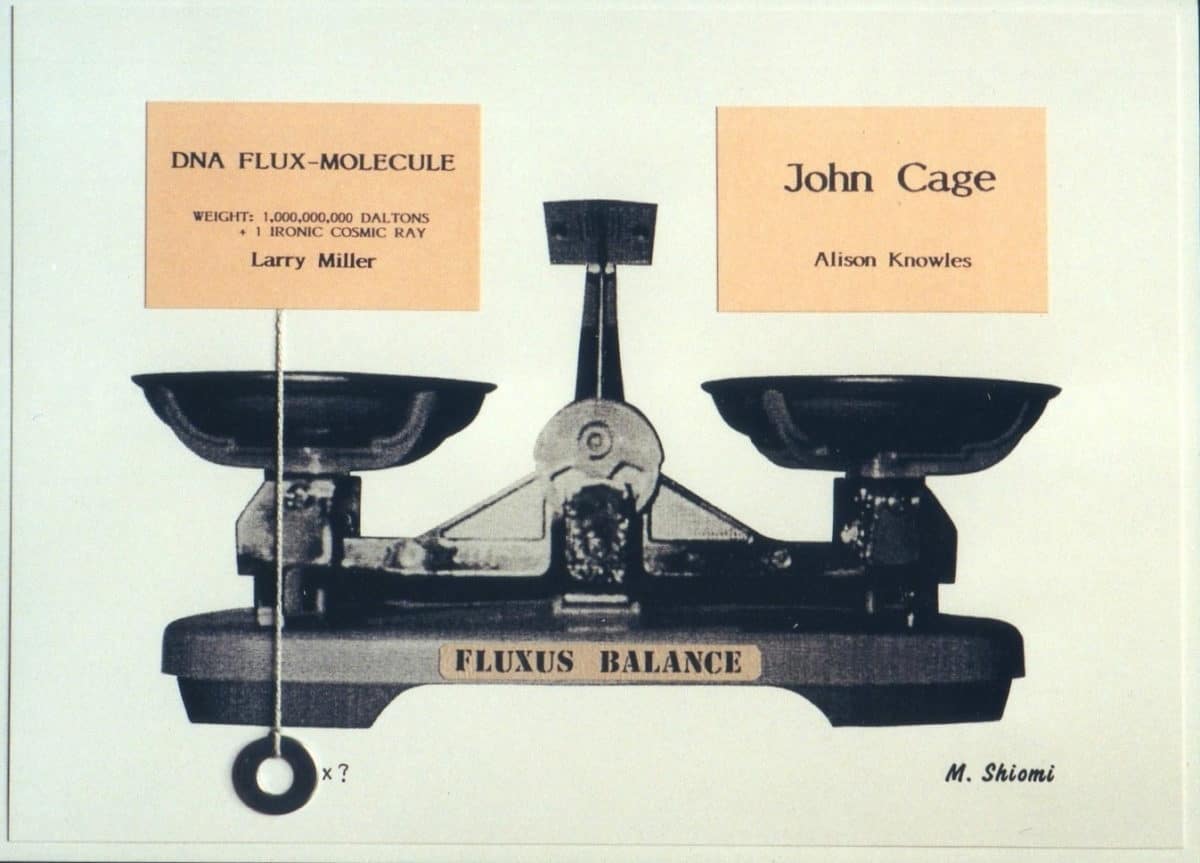

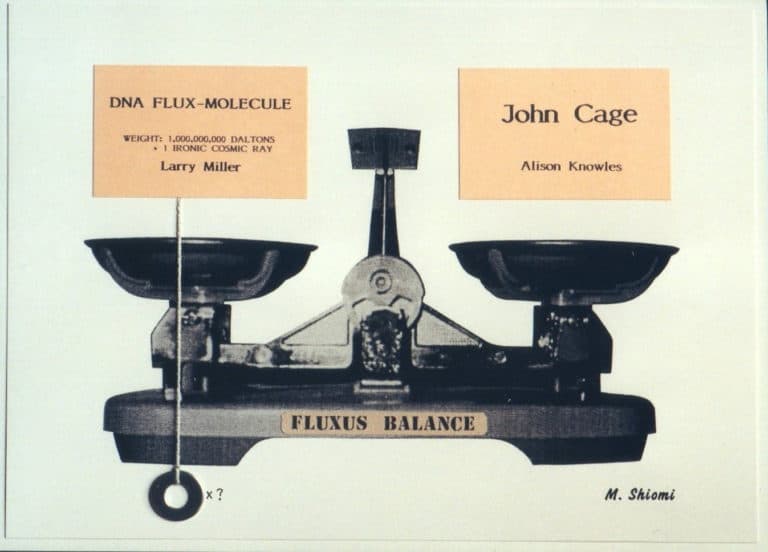

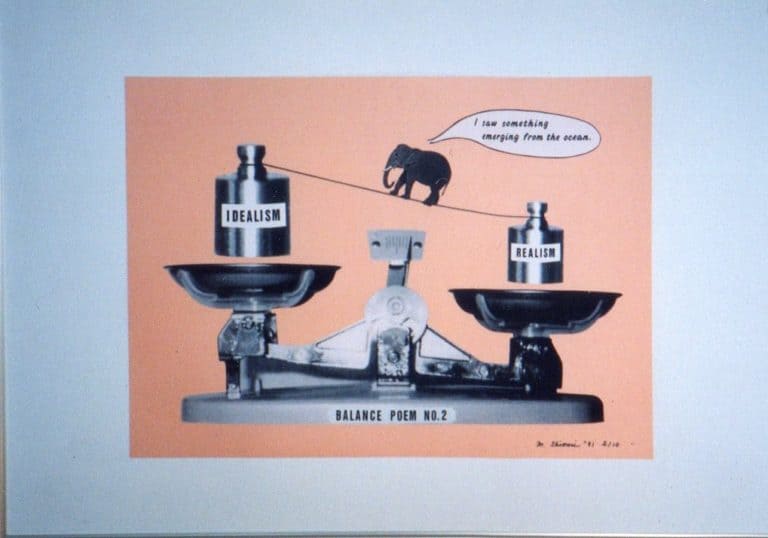

In the 1990s, I did Fluxus Balance as a mail Event with Fluxus peers and friends. I asked them to “write down in one of the squares on the scale what you want to weigh against something that another person wants to weigh.” Of course, they didn’t know what would be placed on the other side of the scale. Because these people were not so simple, each of their replies was elaborate and interesting. This is one of thirty-four scales that I created by matching the cards containing the answers from everybody in 1995 [Fig. 23]. One of the cards by Larry Miller reads “DNA FLUX- MOLECULE. Weight: 1,000,000,000 DALTONS + 1 ironic cosmic ray.” According to him, a dalton (Da) is a measuring unit for molecules. For example, one water molecule weighs 18 daltons. I matched it with Alison Knowles’s “John Cage.” Of course, Cage is heavier, and I tried to make adjustments by adding some weights. In parallel with this work, I also created twenty-four sheets of collages using photos titled Balance Poem [Fig. 24]. A larger weight here says “IDEALISM,” while a smaller one says “REALISM.” But realism weighs more. An elephant is trying to cross a rope and is murmuring something. The series of balance-related works exhibited in the gallery has thus evolved.

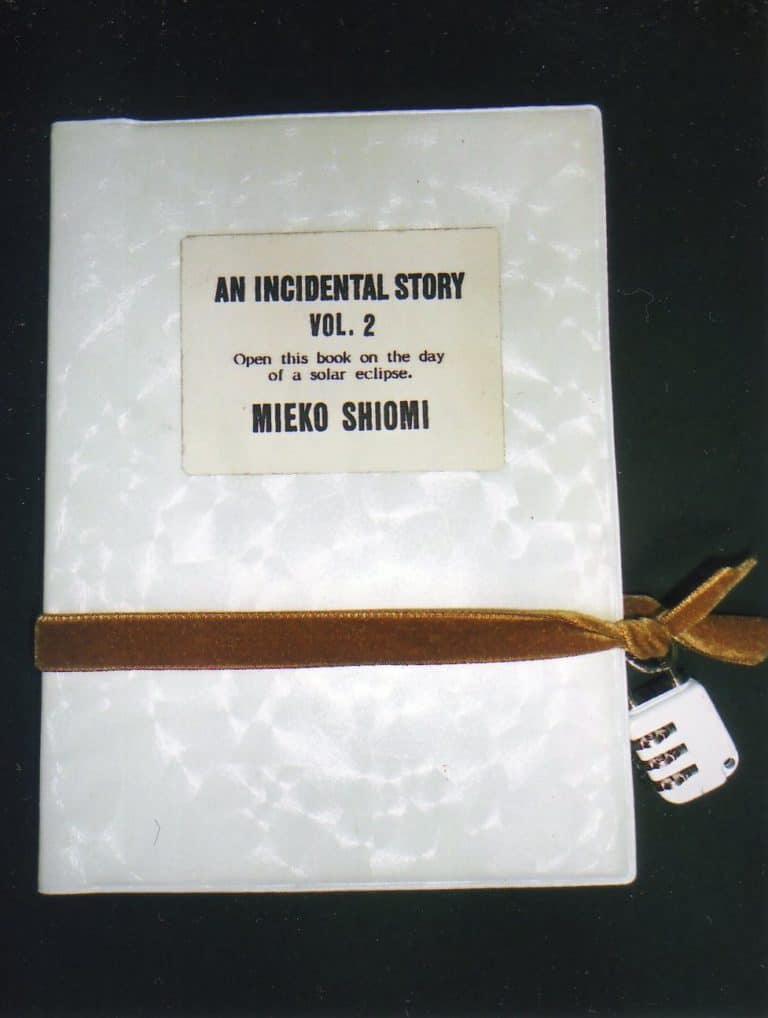

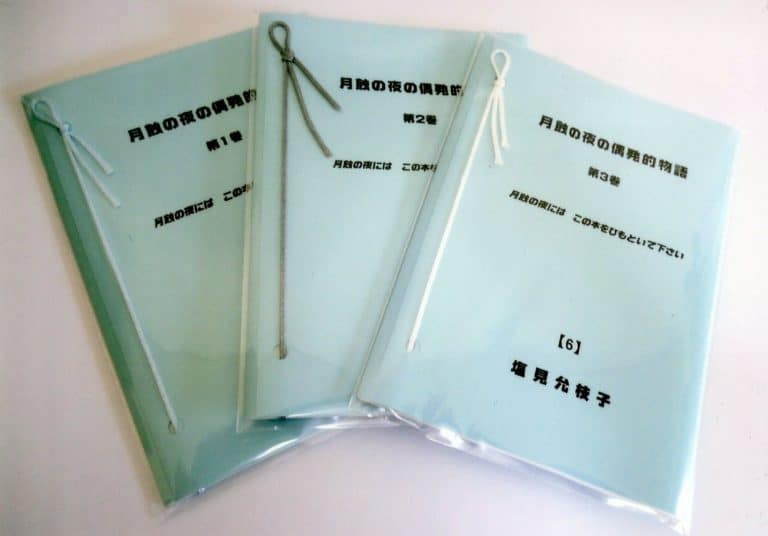

An Incidental Story on the Day of a Solar Eclipse / An Incidental Story on the Night of a Lunar Eclipse

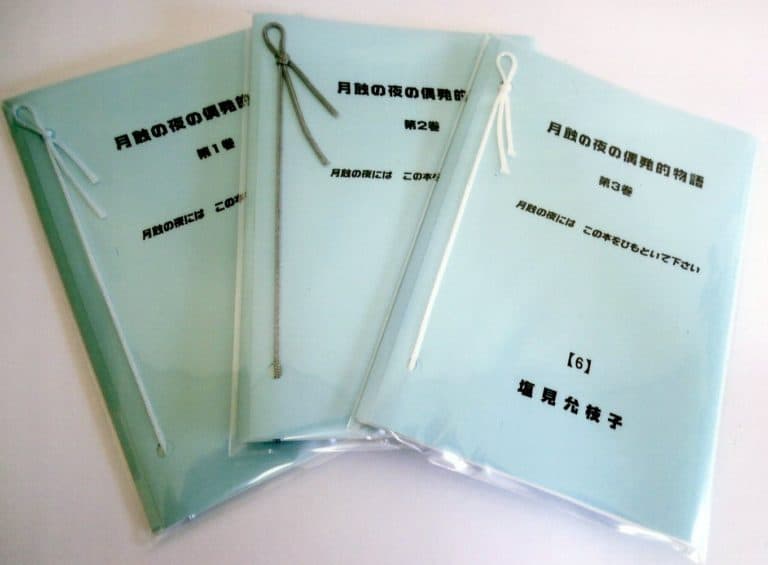

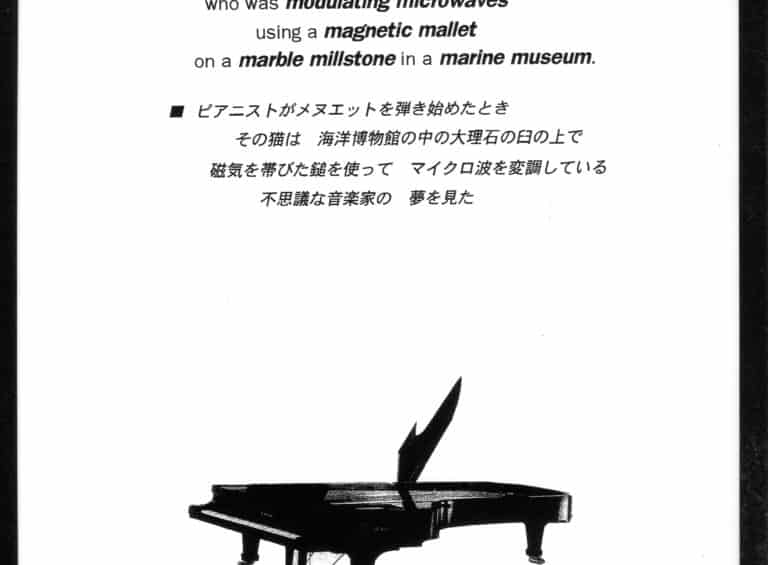

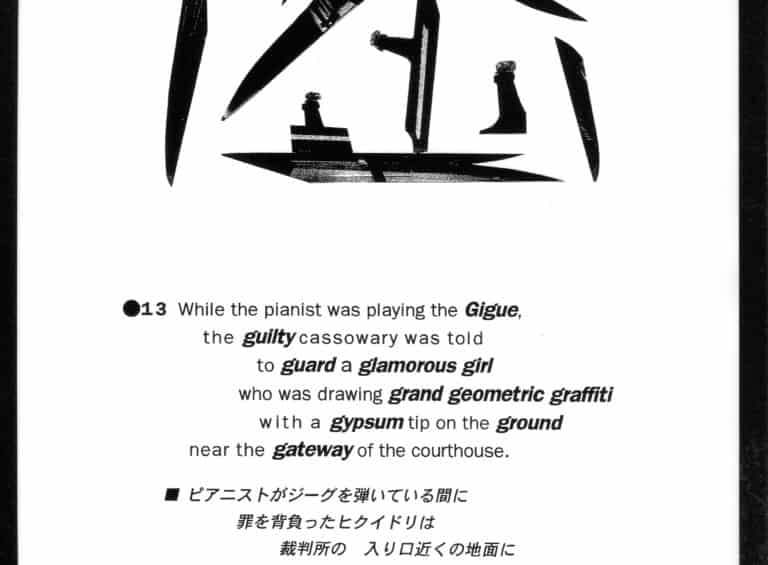

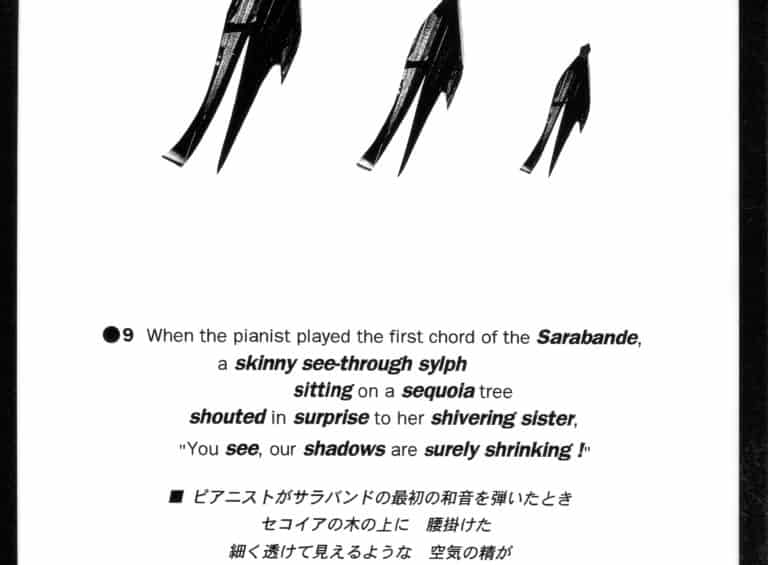

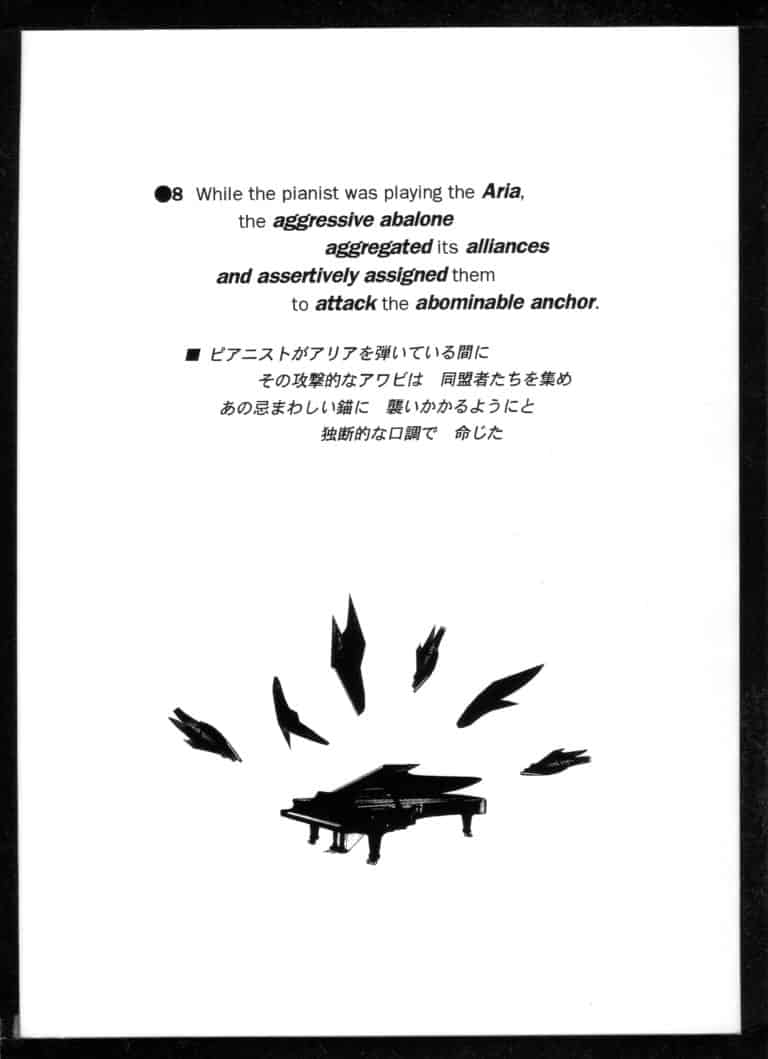

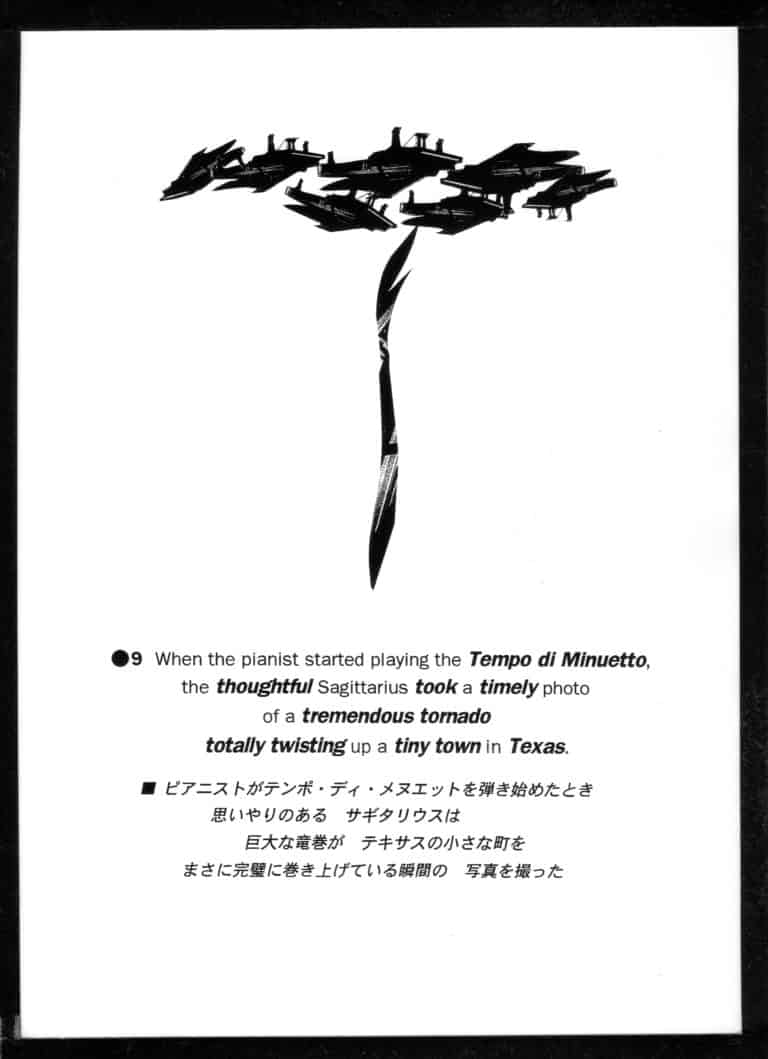

There are many other transmedia pieces, but the most extreme example is a series I began with a book locked with a key, submitted to the Book Object exhibition [Fig. 25]. This is one volume out of three. The content is a short story in English that unfolds while a pianist plays from Bach’s Partitas. Each sentence begins with a word that starts with the first letter of a dance form contained in the music. Later this became a two-dimensional work. This is a photo from an exhibition at Galerie Donguy in Paris [Fig. 26]. It grew into a chamber music piece, An Incidental Story on the Day of a Solar Eclipse, via a simple performance [Fig. 27] that consists of narration, piano, soprano, saxophone, a performer, and environmental sounds from speakers. The recording is being played here in the museum exhibition. The three volumes of An Incidental Story on the Night of a Lunar Eclipse became part of a six-volume book work [Fig. 28]. Bach’s Partitas are made up of six suites. That’s why I made a story corresponding to each of them. Of course, the music and the content of my stories are not related at all. Lastly, I made a picture book in which I rearranged and collaged pictures of a piano in different sizes for the exhibition Dissonances at the Toyota City Museum of Art in 2008 [Figs. 29–33].

Direction Event

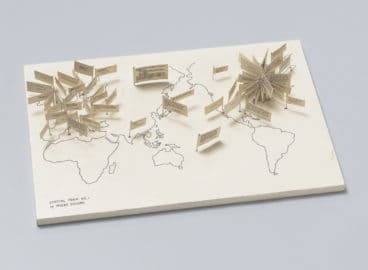

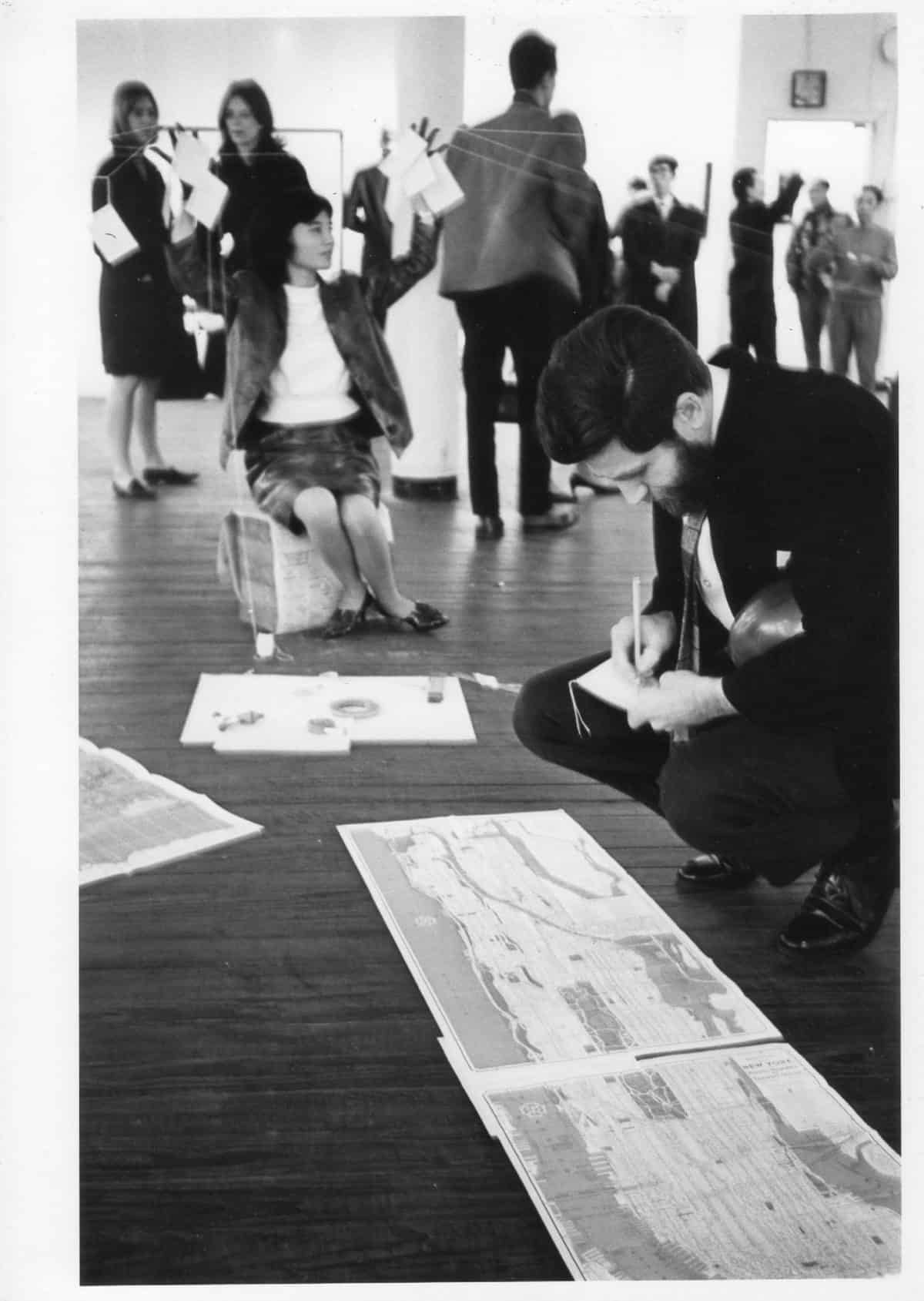

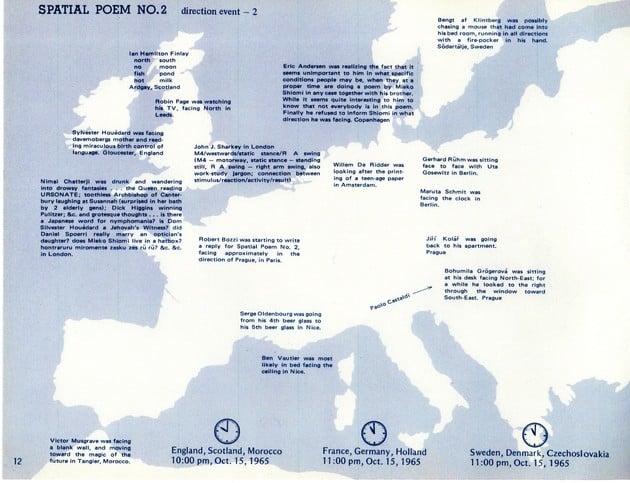

Finally, let me talk about Direction Event. It was originally a performance. This is a picture of the premier at Washington Square Gallery. I was seated, wearing gloves, each finger of which was connected to a long thread [Fig. 34–35]. Ten participants wrote directions on cards for where they wanted to bring the threads, read them, attached the cards to the threads, and pulled the threads in those directions. The man who was squatting over here is Allan Kaprow. I prepared a map and a compass. I don’t remember details, but there were directions such as “toward the window,” “toward the exit,” and “toward a certain place,” in addition to “far from now,” which interpreted directions in terms of time. Later, with people all over the world I did Direction Event through the mail [Fig. 36]. It was the second Event of the Spatial Poem series. There are time gaps, since this Event took place all over the Earth. I sent the participants a list of time gaps in different places and asked them to report what direction each of them was facing at the same particular moment. While there were simple reports such as they were facing the ceiling, a newspaper, or a television, there were also interesting interpretations and calculated performances. Maciunas sent a report saying that he brought a swivel chair into an elevator and pressed the button to go up. While the elevator was ascending, he was rotating at high speed on the chair. Thus he insisted that he was directed toward all three hundred and sixty degrees while ascending. Somebody else reported that his direction varied because he was chasing a mouse that had entered the bedroom. Or a person told me he was “going from his 4th glass of beer to his 5th glass of beer,” and yet another reported that she was “going in the direction of simplification.” Later, I also made a two-dimensional work on the concept of “direction” using a sheet of cardboard and a compass, but in an exchange I gave it to Mr. Nakanishi Natsuyuki of Hi Red Center, so I don’t have it anymore.

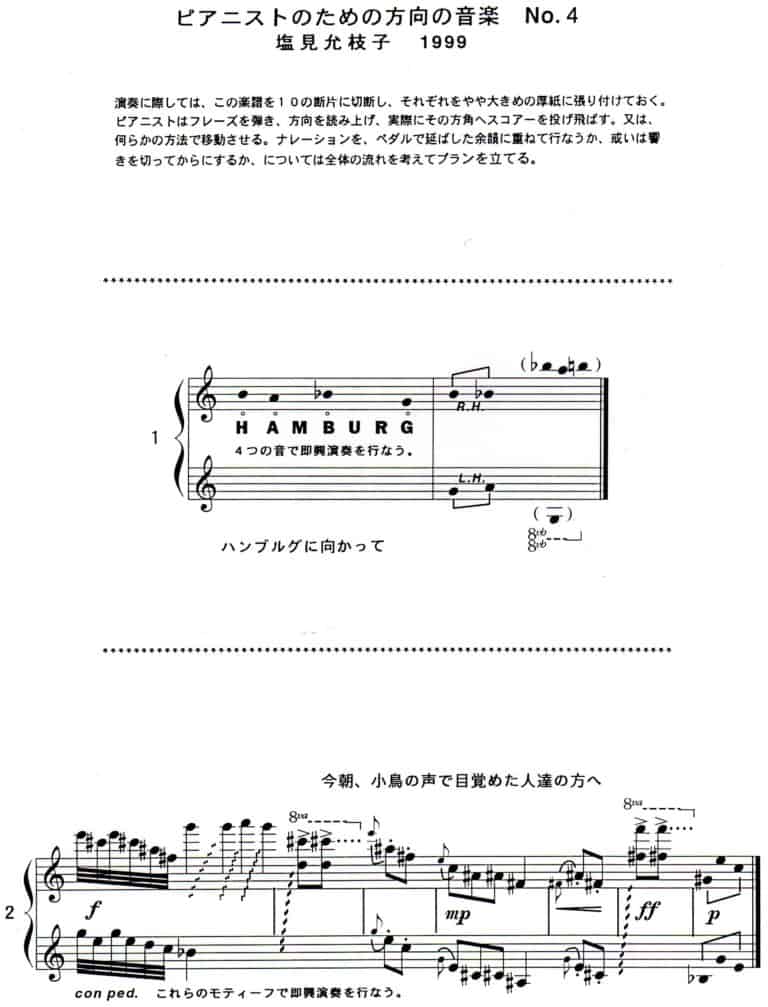

I also composed piano music based on the concept of direction. Titled Direction Music for a Pianist, the directions and sounds vary according to the time, place, and occasion of the performance [Fig. 37]. This is an uneconomical composition method, but it is unavoidable if I take reality seriously. The pianist cuts up the phrases on the original scores, pastes them onto thick cards, and performs from those small score cards. First she plays one phrase and announces the direction written on the card, then she throws the card away in that direction. This is the first page of score No. 4, which was composed for the opening of the exhibition Japan-Germany Visual Poetry, held in Kitakami City. I chose the city of Hamburg as the direction because the exhibition was in exchange with Germany. The name Hamburg contains four letters that represent different notes: H, A, B, and G. After improvising using these four sounds, I threw the score card in the direction of Hamburg. This was score No. 2, performed at the 1994 Fluxus Reunion Concert in New York [Fig. 38]. Because of the special occasion, I added some suitable directions such as “toward the house in Kaunas where Maciunas was born” to the general directions. After playing the piano, I read the directions in Japanese and asked others to read them in English, French, Danish, and German, in a slightly overlapping, staggered fashion. Of course, they had been translated in advance. The white thing diagonally above the piano in this photo is the score. Performers were: [from left to right] Jessica Higgins, a daughter of Dick Higgins and Alison Knowles; Jean Dupuy, the French poet; Danish artist Eric Anderson; and Ben Patterson. Ben is an American artist known in Japan as well, but he lives in Germany now. I’m looking forward to today’s performance of the totally new version of this Direction Event by eight people.

Thus, I’ve enjoyed transforming one concept into various forms using media I was familiar with. I would like to ask you one favor. I would like you to participate in this Direction Event today. Please write on the cards that have been distributed the directions that you’ll be heading in when you leave the museum, after this event is over. You can be anonymous. The directions can be spatial, temporal, or more conceptual or abstract. It would be wonderful if you could use words like “toward” or “to” or “aiming at.” After all the performances are over, we will read your submissions. This means that all of you will perform this Direction as a sort of anonymous group. You will be the subject.

Thank you very much for listening to me for a long time.

Note: This essay was translated by Midori Yoshimoto and edited for publication on post. The original Japanese text was published in the 2012 Annual Report for the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo (MOT). The Japanese version is available here on the MOT website. Shiomi’s text starts on page 96 of the linked PDF.

- 1In the German musical system, “H” refers to the seventh scale degree, and the “B” refers to the flatted seventh scale degree of a seven-note diatonic scale. —Editor’s note.

- 2Sassi was an avant-garde cultural impresario in Milan and well-known supporter of Fluxus. —Editor’s note.